Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1081

June 8, 2011

Black Muisc Month 2011: "Where is Your Faith?" | Rev. James Cleveland

Published on June 08, 2011 13:14

One 'Man Down'; Rape Culture Still Standing

One 'Man Down'; Rape Culture Still Standing by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan

Art should disturb the public square and Rihanna has done just that with the music video for her song "Man Down," directed by long-time collaborator Anthony Mandler. The song and video tell the story of a casual encounter in a Jamaican dancehall, that turns into a rape, when a young woman rejects the sexual advances of the man she has just danced with. Much of the negative criticism directed at "Man Down" revolves a revenge act, where Rihanna's character shoots her rapist in cold-blood.

Some have found the gun violence in video's opening sensationalist and gratuitous. The Parents Television Council chided Rihanna, offering that "Instead of telling victims they should seek help, Rihanna released a music video that gives retaliation in the form of premeditated murder the imprimatur of acceptability." Paul Porter, co-founder of the influential media watchdog Industry Ears, suggested that a double standard existed, noting that, "If Chris Brown shot a woman in his new video and BET premiered it, the world would stop." Both responses have some validity, but they also willfully dismiss the broader contexts in which rape functions in our society. Such violence becomes a last resort for some women, because of the insidious ways rape victims are demonized and rapists are protected in American society.Part of the problem with Rihanna and Anthony Mandler's intervention, is the problem of the messenger herself. For far too many Rihanna's objectivity remains suspect in the incidence of partner violence, that was her own life. As a pop-Top 40 star who has consistently delivered pabulum to the masses, minus any of the irony that we would assign to Lady Gaga or even Beyonce, there are some who will simply refuse to take Rihanna seriously—dismissing this intervention as little more than stylized violence in the pursuit of maintaining the re-boot. Porter, for example, argues that BET was willing to co-sign the video, which debuted on the network, all in the name of securing Rihanna's talents for the upcoming BET Awards Show. It's that very level of cynicism that makes public discussions of rape so difficult to engage.

I imagine that much less criticism would have been levied at Erykah Badu, Marsha Ambrosias or Mary J. Blige for the same intervention, in large part because they are thought to possess a gravitas—hard-earned, no doubt—that Rihanna doesn't. This particular aspect of the response to Rihanna's "Man Down" video highlights the troubling tendency, among critics and fans, to limit the artistic ambitions of artists, particularly women and artists of color. Rihanna's music has never been great art (nor should it have to be), but that doesn't mean that the visual presentation of her music can't be provocative and meaningful in ways that we nominally assign to art. Additionally, responses to "Man Down" also adhere to the long established practice of rendering all forms of Black expressions as a form of Realism, aided and abetted by a celebrity culture that consistently blurs the lines between the real and the staged.

Ultimately discussions of "Man Down" should pivot on whether the gun shooting that opens the video was a measured and appropriate response to an act of rape. Perhaps in some simplistic context, such violence might seem unnecessary, yet in a culture that consistently diminishes the violence associated with rape, often employing user friendly euphemisms like sexual violence—as was the case in the initial New York Times coverage of a recent Texas gang rape case—rather than call a rape a rape. As an artistic statement, intended to disturb the public square, Rihanna's deployment of the gun is an appropriate response to the relative silence associated with acts of rape, let alone the residual violence that women accusers are subject to in the denial and dismissal of their victimization with terms like "she deserved it," or "she was asking for it" because of her style of dress.

One wishes that as much energy that was expended criticizing Rihanna's video for its gun violence was expended to address the ravages of the rape culture that we live in. One man may be down, but rape culture is still standing.

***

Mark Anthony Neal, a Professor of African-American Studies at Duke University, is the author of five books, including the forthcoming Looking for Leroy and the co-editor (with Murray Forman) of That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader (2nd Edition) which will be published next month. Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan

Published on June 08, 2011 08:56

Hip-Hop is Gay: Seeing Mr. Cee

Hip-Hop is Gay: Seeing Mr. Cee by James Braxton Peterson | special to NewBlackMan

Hip Hop is gay. Not in the colloquial/vernacular sense of 'gay' as something negative or deplorable, but gay as in actually gay. I am gay too – about the possibility of actually having a real conversation about human sexuality, human resources and Hip Hop culture. It's high time that Hip Hop had some real discourse about the homophobia that plagues us socially and I think at this point any other front(ing) is simply a thin veneer for the Hip Hop community's inability to embrace the sexual reality of this culture that we know, love, and sometimes hate.

Recently, HOT97's Mr. Cee (ne Calvin LeBrun) was arrested for public lewdness when police allegedly saw him receiving oral sex from another man in his car. According to the New York Daily News this is the third time that (in less than a year) Mr. Cee has been caught/detained for solicitation, loitering and now public lewdness. Even more recently, Mr. Cee pled guilty to lewd conduct in public. As J. Desmond Harris reported on The Root.com, the online response to Mr. Cee's predicament was typically homophobic and at times downright ignorant. To my mind this is simply more evidence that Hip Hop is gay.In his award-winning documentary, Beyond Beats and Rhymes, filmmaker Byron Hurt unveils hypermasculinity and homosocialism as foundational pillars in the construction and performance of black masculinity in Hip Hop culture. The film also suggests that some of the rampant hypermasculinity, misogyny, and violent themes are ways in which men attempt to over compensate for their own homoerotic and homosocial desires. As more and more narratives like Mr. Cee's emerge, the response to the alleged activities/crimes seem to be more indicative of Hip Hop culture than the actual alleged acts in question.

For his part, Mr. Cee originally denied these allegations, shielding himself in a playlist of oddly defensive rap tracks, and ramping up a twitter account so that he can defend himself against the perceived 'plague' of being gay in the homophobic world of Hip Hop. There are several situations in the not so distant past that have unraveled similarly in the public sphere. Eddie Murphy was arrested for a rendezvous with a transgendered person and rumors of him being gay have pretty much dogged him ever since. In a more honest discourse we might be able to consider that Eddie is more bi-sexual than gay, or better still, he, like many folk, have sexual preferences that can not simply be defined by hetero/homo terms.

You might also remember that New Jersey governor (McGreevey) who frequented Turnpike truck stops in order to satiate his socially repressed desires to be with other men. Or you might likewise recall Ted Haggert's scandalous meth-drenched affair with a 'personal trainer', or former Senator Larry "wide stance" Craig's arrest for lewd conduct. Maybe you haven't seen the self-photograph of a svelte Bishop Eddie Long, in full pose – making a virtual/visual gift for his young targets of seduction. Bishop Long also, very recently settled his case. Mr. Cee is not the first and certainly won't be the last public figure to be "guilty of" engaging in gay sexual activity.

Yet his recent plea, the responses, defenses and protests tell a powerful story of repression and utter fear of severe social rebuke. For the ministers and senators, their professional anti-gay rhetoric belied their personal gay desires. If we situate Mr. Cee's alleged activity within the context of a long history of homophobia in Hip Hop – and here I am thinking specifically of the ways in which Wendy Williams stoked the flames of hatred and fear in the very first gay-rapper witch-hunt-like scandal. Nothing really came out of it except for the violent verbal attacks on Wendy Williams and the vehement denials of any rapper ever even having a gay thought.

Seriously, we cannot at this point in time as adult constituents of Hip Hop culture believe that no rapper (or DJ/producer) has or will ever be gay. It just doesn't add up and this is not to weigh in on how/why you think people are gay – whether you think they are born that way or they somehow 'choose' their sexual preferences. Somebody in Hip Hop must be gay, but for me, our exceeding willful denials of this fact simply belies our culture's repressed gay identity. We're much like those ministers and senators who protest gay sexuality/marriage just a little too much – or just enough to signal the repression of deep-seeded gay sexual desires.

In Hip Hop this repressive denial often takes the shape of hypermasculine narratives with a no-homo brand of homophobia functioning as the frosting on the cake. Check out Funkmaster Flex's seething defense of his homie Mr. Cee delivered in response to a rival station's bit about Mr. Cee's alleged public fellatio scenario. Flex goes on for at least five minutes straight, berating the entire station, defending Mr. Cee, and intimating that (gasp) there may be some folk at that other station who are actually gay, not (as Flex suggests re: Cee) framed by the NYC Hip Hop police.

But let's pretend for minute that Mr. Cee is gay. Does that mean that his show, "Throwback at Noon" isn't hot like fire? Does it diminish his pivotal role as Big Daddy Kane's DJ? Is Ready to Die any less dope to you now than it was before you thought about the possibility that Mr. Cee was gay? I hope that you answered NO to all of these rhetorical questions and I hope that starting now the Hip Hop community can at last be persuaded to confront its irrational fear of the full range of our community's human sexuality.

***

James Braxton Peterson is Director of Africana Studies and Associate Professor of English at Lehigh University and the founder of Hip Hop Scholars, LLC. Follow him on Twitter @JBP2.

Published on June 08, 2011 08:41

Dyana Williams: 'The Mother of Black Music Month'

Dyana Williams , long-time radio personality, music industry insider, and current host of Soulful Sundays on WNRB (107.9 | Philadelphia) discusses the founding of Black Music Month.

Published on June 08, 2011 08:05

June 7, 2011

The Big Loser: Racism and the Unfight against Health Disparities

The Big Loser: Racism and the Unfight against Health Disparities by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackMan

Having just completed its 11th season, The Biggest Loser is changing the national landscape. The question, however, is how is the show transforming society. According to JD Roth, one of producer of The Biggest Loser and one of the newest weight loss shows – Extreme Makeover: Weight Loss Edition – argues that these shows are on the frontlines of the battle against systemic obesity: "The first step to changing some systemic problem in society is awareness and I think (weight) awareness is at an all-time high."

While unsuccessful in initiating a weight loss revolution, the show has been successful in revolutionizing television. The success and cultural capital afford to The Biggest Loser (its not just a show but a public service trope) has generated several copycat shows including The Biggest Loser in twenty-one countries. Each of these shows universalize the issue of obesity erasing fissures, divisions, and inequalities. More importantly, these shows reduce the issue of weight and health to a matter of choice. "All borrow a basic set of assumptions from "The Biggest Loser" writes Aaron Barnhart. "Obesity is largely a product of inertia, of spending too much time sitting around eating terrible food. The cure, therefore, is activity — lots of it, with occasional breaks to make healthy meals and visits to the confession-cam." David Grazian, in "Neoliberalism and the Realities of Reality Television," describes The Biggest Loser as yet another reality-based show that pivots on the tenets of neoliberalism:

Although the very design of competitive reality programs . . . guarantees that nearly all players must lose, such shows inevitably emphasize the moral failings of each contestant just before they are deposed. In such instances, the contributions of neoliberal federal policy to increased health disparities in the U.S.— notably the continued lack of affordable and universal health care, and cutbacks in welfare payments to indigent mothers and their children—are ignored in favor of arguments that blame the victims of poverty for own misfortune.

Writing about another reality show, Master Chef, Evan Shartwen argues that reality shows and the economic philosophy of neoliberalism (defined by its promotion of "free markets, economic liberalisation, efficiency, consumer choice and individual autonomy") share a mutual "emphasis on personal development and learning new skills."

The popularity and interest in The Biggest Loser, as a non-state capitalist intervention against a national health crisis, reflects the extent of America's collective weight issues. The numbers are telling. 34% of adults are obese with another 34% in the overweight category. For kids, things are equally troubling with 18% of kids ages 12-19 and 20% of those ages 6-11 defined as overweight.

This issue is particularly acute within the black and Latino communities. Nationally, 38.2 and 35.9 percent of African American and Latino youth, ages 2-19, are obese and overweight, compared to 29.3 percent of whites within this same age group. In nine states, adult obesity for African Americans exceeds 40 percent with that number between 35-39.99% for 34 states. "Strikingly, the link between race, poverty and obesity is most acute in the South, our nation's most impoverished region" writes Angela Glover Blackwell. "In Mississippi, which has an African American population of more than 37 percent and is the poorest state in the country, the obesity rate is the highest of any state, as is the proportion of obese children ages 10-17." Worse yet, despite attention and a national discourse, the obesity issue doesn't seem to be getting better, especially when we look within (poor) communities of color. Between 1986 and 1998, childhood obesity rates within the African American and Latino communities increased by almost 120 percent, whereas whites only saw an increase of 50 percent over this same period. According to the NAACP, "these rates have roughly doubled since 1980." It has been estimated that roughly 60 percent of Native Americans living in urban communities are overweight or obese.

While often erasing the inequalities and disparities evident in America's obesity epidemic, the limited focus on differences in obesity rates tends to individualize and pathologize the issue within communities of color. Often times, commentators focus on cultural differences, food choices, and varied definitions of body image to explain differential rates of obesity. For example, in a recently released study from the Boston Public Health Commission, the issue of obesity amongst youth is directly tied to soda consumption. It found that greatest levels of consumption of sugary, sweetened drinks are amongst poor black and Latino youth. While certainly an issue (and one that reflects a myriad of issues from availability, advertisements, school reliance on soda monies), the hyper focus on food and drink consumption in relationship to personal choices limits our understanding of this issue.

Similarly, another ubiquitous theme has been how high rates television watching and video game play amongst youth of color contribute to high obesity rates. "Research suggests that low-income and ethnic minority youth are disproportionately exposed to marketing activities," writes Shiriki Kumanyika. "A Kaiser Foundation report found that among children eight to eighteen years old, ethnic minorities use entertainment media more heavily than majority youth do. African Americans and Hispanics spend significantly more time watching TV and movies and playing video games than do white youth." A complex issue, the nature of the discourse pathologizes and restricts our focus to individual choices and experiences.

The Biggest Loser is no different evident in the narrative focus on cultural acceptance of larger body types within certain Pacific Islander communities or even its linking of Tiger Moms to weight gain among a single contestant. Yet, at a larger level the issues are presented as that of individuals who have made bad choices. While rarely explicitly acknowledged, the show seems to have a disproportionate number of working-class white contestants, with a handful of people of color each season. As such, the backdrop for the show is a white racial frame that tends to demonize the poor, particularly poor people of color. The Biggest Loser, as with much of the discourse surrounding America's obesity epidemic, tends to erase structural inequalities and segregation; it ignores how obesity rates and related health problems are a form of racial state violence.

In erasing history, institutional (environmental) racism, segregation, and persistent inequality policy discussions, popular culture representations and the public debate at large continues to blame poor communities for the issue of obesity by focusing on bad choices, parenting, and other factors that can be easily corrected. As long as one follows the instructions of The Biggest Loser trainers to workout harder, eat better food (including their endless products placed within the show) and otherwise change their ways, people have the potential to be healthy. That is the lesson of the show. Not in reality.

According to Silja Talvi in "Bearing the Burden: Why are communities of color facing obesity and diabetes at epidemic levels": "Over 60 percent of all Americans are now overweight, and experts agree that fast food, television, office jobs, lack of fresh fruits and vegetables in school lunches, and genetic factors have all conspired to make Americans of all ages fatter. But for people of color and poor people, the issues are even more complex and far-reaching." Studies have consistently illustrated that when accounting for class and circumstances, the discrepancies in rates of obesity between whites and blacks and Latinos are virtually nonexistent. The Washington State Department of health found that racial discrepancies here are lessened when controlling for income, education, age, and gender, although inequalities remain a reality. Yet, the inequalities exist, demonstrating the ways in which segregation, history, privilege, and a myriad of other factors operate in the context of these health issues. "Some of the intervening factors that affect obesity rates in Hispanic and black communities include eating patterns and accessibility to healthy food options, notes Sonia Sekhar in "The Significance of Childhood Obesity in Communities of Color."

Studies ubiquitously illustrate the segregation has effectively cut off poor communities of color from affordable healthy food. Scholars in Australia found individuals living in poor communities have 2.5 times more contact with fast food restaurants than those living in upper-class communities. Equally important, the report highlighted that these stores sell a very limited amount of fresh fruit, vegetables and meat, providing ample processed food. According to John Robbins, people of color are more likely to find foods that are high in fat, salt, refined carbohydrates and sugar compared to whole grains, fresh vegetables and fruits, and organic foods which are difficult if not impossible to procure within many poor urban communities. A North Carolina study concluded that only 8 percent of black residents lived in close proximity to a supermarket compared to 31 percent of whites. Another study in North Carolina found that the mere presence of at least one supermarket within black neighborhoods had a positive influence on the reducing fat intake (25 increase versus 10 percent for white neighborhoods). And it isn't just about the type of foods, but the cost as well.

The Healthy Foods Healthy Communities report found that on average those smaller convenience stores/gas stations/corner markets that are commonplace within America's urban centers charge between 10-49 percent higher than chain supermarkets. A study in Great Britain from Food Magazine found that eating healthier costs at least 50% more, a number that increases to 60% when looking at poor communities.

Food insecurity and the lack of access to quality and healthy foods are not the only evidence of how racial inequality contributes to and is evident in America's obesity epidemic. It is equally visible in thinking about recreation, leisure, and play. Research has shown that people of color and particularly lower-income communities have fewer opportunities for physical activity. For example, several studies published within the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (AJPM) found "that unsafe neighborhoods, poor design and a lack of open spaces and well constructed parks make it difficult for children and families in low-income and minority communities to be physically active." Likewise, citing the study from Trust for America's Health (TFAH) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) entitled "F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America's Future 2010" Blackwell focuses on the structural impediments to a healthy lifestyle that includes exercise. "As the report illustrates, where we live, learn, work and play has absolutely everything to do with how we live. Low-income families of color are too often disconnected from the very amenities conducive to leading healthier lives, such as clean air, safe parks, grocery stores with fresh fruits and vegetables, and affordable, reliable transportation options that offer access to those parks and supermarkets."

Robin D.G. Kelley described this predicament in "Playing for Keeps," as part of structural adjustment programs and deindustrialization, processes that plague poor communities of color beginning in the 1970s. "Play areas -- like much of the inner city -- have become increasingly fortified by steel fences, wrought-iron gates, padlocks, and razor sharp ribbon wire" (1998, p. 196). Noting that in cities like Cleveland and New York City, which each saw closure of between 40 and 50 million dollars worth of recreation facilities in the late 1970s, Kelley argues that play and spaces of recreation have increasingly only been accessible within middle-class (white) suburban communities.

We have witness a growing number of semipublic private spaces like 'people's parks' that require a key . . . and highly sophisticated indoor play area that charge admission. The growth of these privatized spaces has reinforced a class segregated play world and created yet another opportunity for investors to profit from the general fear of crime and violence. This, in the shadows of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsed's great urban vision of class integration and public socialability, high-tech indoor playgrounds such as Wondercamp, Discovery Zone and Playspace, charge admission to eager middle- and upper-class children whose parents want a safe play environment . . . . While these play areas are occasionally patronized by poor and working-class black children, the fact that most of these indoor playgrounds are built in well-to-do neighborhoods and charge an admission fee ranging between $5 and $9 dollars prohibits poor families from making frequent visits (1998, p. 202).

A study in Great Britain found not only that neighborhoods that are a majority white are 11 times more likely to have "green space" but also "that people's level of physical activity and health was directly related to affluence and the quality of green space."

The consequences of restricting play to the well-to-do communities, of limiting access to recreation, and otherwise maintaining a system of de facto segregation when it comes to physical activity, are evident in the health disparities. The consequences a system of food access determined by race, class, and geography is evident in the shameful health inequalities. The consequences of a national conversation and policy about obesity guided by a neoliberal fantasy based on choice, values, and priorities are evident in not only disparities in weight numbers, but diabetes, hypertension and countless other diseases. According to Grazian, "On reality weight-loss programs, there are no collective solutions to rampant inequalities in wellness and health—say, an organized boycott of inner-city supermarkets that do not sell fresh yet inexpensive pro-duce—only individual moral failures that can be repaired by a belligerent drill sergeant, breaking down the souls of his charges in a televised theater of cruelty that lasts until the season finale."

The celebration of corporate interventions and the racially-charged backlash against Michelle Obama's efforts to transform societal views on nutrition and exercise is an assault on "personal choice and responsibility" illustrate the power of shows like The Biggest Loser. Profit generated and corporate driven programs to address the obesity epidemic, notwithstanding the lack of substantive results (improvement) are a fixture of a neoliberal society. It is no wonder that The Biggest Loser is imagined as revolutionary. The obesity epidemic and the structural inequalities that are particularly threatening youth of color mandate structural changes not individual transformations fostered by the marketplace.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press).

Published on June 07, 2011 16:28

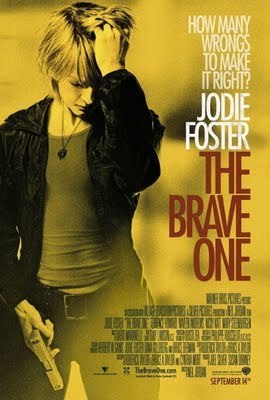

Woman Up: 5 Revenge Films to Watch and Discuss

Woman Up: 5 Revenge Films to Watch and Discuss by Black Artemis | Better Than Keepin' It Real

Because Rihanna's Man Down is only the latest attempt in popular media in which a victim becomes a vigilante, I find the controversy it has generated almost laughable. The vigilante trope is as American as running pigskin down a field. It made Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson movies stars in the 70s and now keeps Nicolas Cage on top of his IRS installment agreement. Regardless of where we stand on the morality or effectiveness of vigilantism, we generally accept that violence begets violence.

That is, until the victim-become-perpetrator is a woman.

Even though we cannot get our fill of the steady buffet at the Cineplex of men wrecking havoc in the name of vengeance, let a woman bring wreck, and controversy ensues. Meanwhile, the men in these narratives are rarely themselves the victims never mind survivors of sexual assault.* Rather they seek revenge for a crime committed against someone they love -- almost always an adult female relative (most likely a love interest) or minor child.

Apparently, Hollywood realizes that we are not ready to see a man go HAM because someone fucked with his brother, male lover or even adult child. This is because we cling to a clusterfuck of patriarchal beliefs that insist:

1. A man can possess a woman or child.2. A man cannot be possessed by anyone else but himself.3. A man who fails to protect his human possessions should be able to redeem himself by regulating those who violate him by messing with them.

It then goes to reason that, despite our taste for tales of vigilantism, any narrative in which a woman who experiences a crime then takes justice into her own hands will prove unsettling. Where does she come off regulating anyone's behavior as if she owns anything including her own body?

Read the Full Essay @ Better Than Keepin' It Real

Published on June 07, 2011 06:58

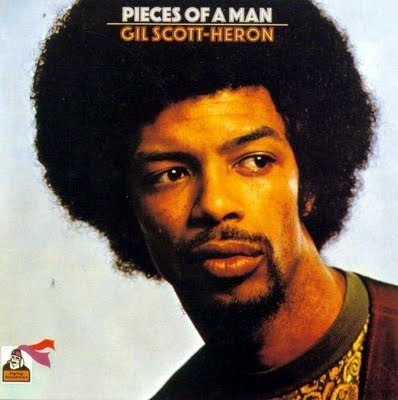

Hubert Laws and Mark Anthony Neal Discuss Gil Scott-Heron on NewsTalk Ireland

Remembering Gil Scott-Heron

NewsTalk Ireland 106-108fm

The Green Room | with Orla Barry

Guest:

Hubert Laws, Jazz Musician

Mark Antony Neal, Duke University Professor

Listen Here

Published on June 07, 2011 06:14

June 6, 2011

America's Most Livable City? | New Video by Jasiri X

from Jasiri X:

"America's Most Livable City" highlights the city of Pittsburgh's recent honor, despite according to the U.S. Census Bureau, having the highest rate of poverty among working age Black people in the United States. This is the Pittsburgh they don't show when your watching the Steelers, the REAL Pittsburgh.

To see more footage of these poor undeserved communities and the Black Men stepping up to provide solutions go to to view our series, "Is Pittsburgh America's Most Livable City?"

LYRICS

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityPlease ignore the invisibles with meSee Pittsburgh rebuilt it's economyBut we still lead the Nation in black poverty

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityJust ignore the invisibles with meAnd state ya business, cause here the place ya livingdepends on ya race and privilege

They call it Clipsburgh PistolvaniaWhere block dictators will launch missiles to bang yaWhere hot metal come whistling out the chamberTo maim ya twisting you like wrestlemaniaAnd what's crazier the bishop wont pray for yaYa families so poor they can't even afford a crate for yaAnd in them skyscrapers Brah they can't wait for usTo move out the hood so they can take it lace it upTransit cuts a brother can't even take the busThis is the ugly truth no need to make it upThen some magazine comes along and places usAs most livable in the USA what?Say what? Guess they didn't survey usCause life is cut shorter than razors where they raise usJudges are racists and quick to hang usAnd police taze us until we never wake up

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityPlease ignore the invisibles with meSee Pittsburgh rebuilt it's economyBut we still lead the Nation in black poverty

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityJust ignore the invisibles with meAnd state ya business, cause here the place ya livingdepends on ya race and privilege

And downtown it's a bunch of new buildingsGlass and steel cathedrals the cost a few millionThey make billions to treat a dudes illnessWith medicine and pharmaceuticals so who's dealingBut the schools are failing screw childrenJust make sure the office has a see through ceilingPitt University and CMU killinclasses cost thousands I don't see you fill emHow we gonna get a job in biotechnologyif all we ever learn is survival psychologyand why we so poor if yall revived the economybut we don't get nothing besides and apologyTear down the projects and put up a targetthen build new homes so they can stimulate the marketBut move us out the neighborhood so we can never harvestthe only thing we guaranteed in Pittsburgh is charges

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityPlease ignore the invisibles with meSee Pittsburgh rebuilt it's economyBut we still lead the Nation in black poverty

Welcome to America's Most Livable CityJust ignore the invisibles with meAnd state ya business, cause here the place ya livingdepends on ya race and privilege

Published on June 06, 2011 14:15

Black Music Month 2011: The Emotions | "Peace Be Still" (from Wattstax))

Published on June 06, 2011 13:55

Black Music Month 2011: Lisa Fischer | "How Can I Ease the Pain" (1991)

Published on June 06, 2011 08:41

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.