Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1075

July 1, 2011

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | Day #1: Stevie Wonder's "That Girl"

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music Day #1: Stevie Wonder "That Girl"by Mark Anthony Neal

Stevie Wonder has had dozens of songs that have topped the R&B/Soul charts, including "That Girl" which was one of the original recordings that appeared on his 1981 greatest hits collection Original Musiquarium I. Though it's likely not the 1st (or 2nd) Stevie Wonder song that one might recall if pressed, the song is notable because it topped the R&B charts in the late winter and spring of 1982 for 9 weeks—the longest period that any Stevie Wonder topped the R&B charts. The twenty weeks that the song spent on the R&B charts is also a record for Stevie Wonder songs (tied with his tribute to Bob Marley "Master Blaster (Jammin')."

"That Girl" was written during what was arguably Wonder's last great period of creativity—songs that he wrote and recorded during that era like "Lately," (later covered by Jodeci) "All I Do" (which Tammi Terrell and Brenda Holloway both recorded in the 1960s), "Do I Do" (with the late Dizzy Gillespie), "Ribbon in the Sky" and "Happy Birthday," his tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr. are all thought of as critical components of the Stevie Wonder canon.

Little of this mattered to me 29 years ago, when I first spotted "That Girl" for the 1st time that spring on a northbound D Train. My boys and I were IRT cats—the 4 train out of BK, transferring to the 6 train to head to the Bronx. But we had heard that all the cute girls who went to Brooklyn Tech and lived uptown, were taking the IND line. Despite the fact that taking the D train, straight outta Brooklyn, was a major detour for at least two of us, it was worth the trouble. Little did I know that I would meet my future bride that spring on that D train.

As the story goes--embellishing a bit on my "weak ass" game—once I sported "That girl," I began a week long stare-down (in retrospect some crazy ish on a New York City Subway even in the early 1980s). When I finally got up the courage to walk over and ask her name—as the D Train was crossing the Manhattan Bridge—she simply blurted out "Peaches," which threw me a bit for a loop; even then such a name always reminded me of women who go jail for stabbing their husbands with steak knives.

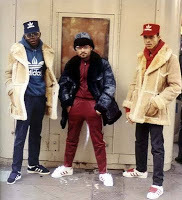

No doubt her decision not to give me her real name—would later find out Peaches was a family nickname—had everything to do with the nerd (and his two nerd friends) who asked the question in the first place. Eschewing the requisite street gear at the time—check Jamel Shabazz's Back in the Day for the time capsule—for Sperry topsiders, Le Tigre knit shirts and an assortment of Members Only jackets ("I'm a thinker, not a lover.") But a brotha trudged on.

No doubt her decision not to give me her real name—would later find out Peaches was a family nickname—had everything to do with the nerd (and his two nerd friends) who asked the question in the first place. Eschewing the requisite street gear at the time—check Jamel Shabazz's Back in the Day for the time capsule—for Sperry topsiders, Le Tigre knit shirts and an assortment of Members Only jackets ("I'm a thinker, not a lover.") But a brotha trudged on.

Published on July 01, 2011 13:47

Can Media Survive? Page One: Inside the New York Times

Can Media Survive? by Esther Iverem | SeeingBlack.com Editor and Film Critic

There is a serious media war going on—and it's not the war over who secures risqué photos of former Congressman Anthony Weiner or even over how the Libya invasion is reported. This is the war chronicled by "Page One: Inside the New York Times," a new documentary that gives us an up-close view of news gathering—in an era when newspapers, including the Times, are fighting for survival.

There has been a dramatic decrease in advertising revenue for newspapers, particularly from bread-and-butter classified ads, which have gone online to Web sites like Monster.com and Craigslist. This decrease, combined with a decentralization of the ability of publish and distribute news content on the Internet, have posed serious challenges for the Times, which, two years ago, borrowed $250 million from Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim Helu, took out a mortgage on its new Manhattan office building and decreased its news staff by 100 positions.

Of course, this financial emergency followed a crisis in newsgathering ethics when it was rocked by the reporting scandals of Jason Blair in 2003 and then Judith Miller. Miller's false stories about the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq virtually led the U.S. into a costly and deadly war, which we still have not exited ten years later.

But "Page One" does not offer a dry recitation of business factoids. Instead, though it, much of this new reality of the media unfolds before our eyes. It follows editors and reporters on a newly created media desk, charged with covering this new and constantly evolving world of media. The star, of sorts, is David Carr, a salty and eccentric veteran reporter who has achieved notoriety for his no- excuses reporting on media and for being a former drug addict.

Read the Full Essay @ SeeingBlack

Published on July 01, 2011 10:03

Cerebral Innovators: Four African American Athletes Who Reinvented Guard Play in the NBA

"Black Jesus"

"Black Jesus"The Lock-out Edition

Cerebral Innovators: Four African American Athletes Who Reinvented Guard Play in the NBA by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Nothing irritates me more in the contemporary popular discourse on race and sports than the presumption that Black athletes have revolutionized the game of basketball, along with other major American sports, largely through strength speed and jumping ability. Such an assumption flies in the face of my own experience, not only as a schoolyard basketball player in Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx—where I met numerous Black players who had only average physical skills, but helped their teams win through their knowledge of the game—but as a close observer and fan of the NBA, where Black athletes changed the game as much through artistry and intellect as through raw physical ability

No where is this more true than in the evolution of guard play in the NBA. From the mid 1950s through the mid 1970s, a revolution in guard play took place in the National Basketball League largely through the influence of four African American athletes whose mastery of the game came through guile, intellect, and a mastery of spacing, angles and spins. At a time when we tend to exoticize Black athletes as physical specimens whose dominant attribute is leaping ability, it is instructive to recall these remarkable individuals who achieved extraordinary success not by outrunning or out jumping their white counterparts, but with body control, anticipation and a uncanny ability to see everything going on around them, a skill set most often associated with athletes like Wayne Gretzky in Hockey and Lionel Messi in soccer.

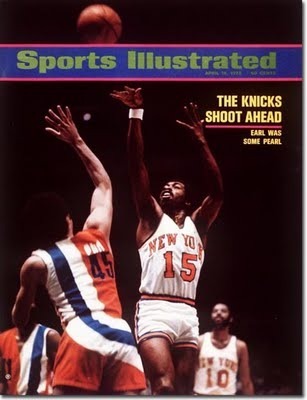

The players I had in mind are Lenny Wilkens, Oscar Robertson, Earl Monroe and Nate "Tiny" Archibald; not one of these players had dunking or high flying acrobatics as part of their arsenal of weapons yet they were unstoppable offensive forces who made their team mates better. For those of you who did not get a chance to see them in person, I want to give brief portraits of each player.

Lenny Wilkens, of mixed African American and Irish ancestry, came out of Brooklyn in the 1950s and was a star at Providence College before playing in the NBA. Though he is perhaps best known as one of the most successful coaches in NBA history, he was an extraordinary force in the league for at least ten years. Less than 6'1" tall, slight of build, Wilkens could get to the basket and score at will even though he only drove left. The key was quickness, timing and an ability to vary the angles of his layups. Everyone knew Wilkens was driving left, but no one could stop him. He understood how small variations in the timing of his drives, as well as his ability to pass accurately when moving at top speed, made trying to block his shots almost impossible. Today, Wilkens legacy is kept alive by guards like Chris Paul. In his time, his game was sheer genius.

Oscar Robertson, Wilkens contemporary, was a very different type of athlete, and in his era was widely regarded as the greatest player who ever lived. Robertson, out of Crispus Attacks High School in Indianapolis and the University of Cincinatti, was a 6'5" guard, 225 pound guard whose shooting and ball handling skills were the equal of guards in the league who were half a foot smaller. But Robertson, who was always close to the top of the league in rebounding and scoring as well as assists, impacted the game as much through his fierce intelligence as his physical skills. Robertson was one of the first guards in the league to protect the ball by backing his defender in and he could do so without losing sight of either the basket or his team mates. As a result, it was virtually impossible to steal the ball from him or to block his shot, which he took from behind his head rather than the top of his leap. With his combination of size, strength, shooting ability and uncanny court vision, Robertson was literally unstoppable.

For most of his career, Robertson averaged 30 points and 10 assists as game and was regarded with awe, respect, and more than a little fear by opponents and team mates alike. By showing how you could move the ball effectively up the court, as well as position yourself to score, with your back to the basket , Robertson single handedly forged a place for a tall player as combination ball handler, passer and scorer, a mantle later taken up by Magic Johnson. One of the key's to his success was his ability to maintain balance and body control with the ball in his possession over all 90 feet of the court. With movements that were economical, graceful, and single mindedly result oriented, never for show, Oscar Robertson dominated the game with his feet firmly on the ground.

Earl Monroe, of Philadelphia and Winston Salem College, took Oscar Robertson's innovations and brought to them to life with a showman's flair when he entered the NBA in the mid 1960s. Whether bringing the ball up the court, or positioning himself to shoot, Monroe had an uncanny ability to spin sided to side, with his back to the basket, without ever losing control of the ball or his body. No one had ever seen a basketball player move backwards and side to side with such grace and speed, leaving defenders confused and crowds shouting in astonishment and joy (his nickname in the Philadelphia schoolyards was "Black Jesus!").

Monroe had an artist's sensibility as well as an artist's grace, but his unique way of moving also created numerous opportunities to score.. Opponents never knew when he was going to interrupt his spins to drive, pull up and shoot, (passing wasn't Monroe's forte!) and when he shot, you never could predict its point of release. Unlike Oscar Robertson whose jump shot was a thing of beauty and had the exact same release point, Monroe's outside shot was a one handed push that he could take in the air or on the ground from a seemingly infinite variety of angles. As a result, even though Monroe, was, at best, an average leaper, with only average foot speed, his shot was virtually impossible to block, and he was a 20 point scorer for most of his time in the league.

Our final basketball innovator was the Bronx's own Nate "Tiny" Archibald out of DeWitt Clinton HS and Texas El Paso. Archibald, in many ways was the second coming of Lenny Wilkens, a 6'1" guard who could drive to the basket any time he wanted to and whose lay ups could not be blocked. Archibald, like Wilkens had an exquisite sense of the geometry of the game, and could vary the trajectory and spin of his layups as well as their release point, making it almost impossible even for tall players with great leaping ability to figure out when the ball was coming out of his hand.

Archibald who could drive right as well as left, unlike Wilkens, added another weapon to Wilkens arsenal of quick slashing drives, using the basket to protect the ball. If a defender looked like he had great position on one side of the basket, Archibald simply continued through to the other side and laid the ball off the backboard in the reverse, with the rim keeping the defender from reaching the ball. None of the extraordinary variations in Archibald's lay ups required him to be more than one or two inches above the rim height, yet he was able to average close to 30 points a game during his early years in the league while having only a mediocre outside shot. Archibald, like the other athletes I have discussed, reinvented the physics of guard play, by pioneering new ways of moving that depended on throwing opponents off balance rather than physically overpowering them.

The snapshot portraits of these great players, all of whom I have watched in action on numerous occasions, one of whom I know personally, should serve as a reminder not to essentialize Black athletes in ways that erase their intellect, creativity, discipline and skill. The modern game of basketball owes a great deal to these four innovators who changed ball handling and scoring from the guard position, and have made it possible for many different kind of athletes, with a wide variety of skill sets, to play that position in this great and increasingly global sport.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on July 01, 2011 06:47

James Braxton Peterson on the Prison Industrial Complex

The Ed Show with Rev. Al Sharpton:

Is Justice Going to the Highest Bidder?

Guests:

Tracy Valazquez, Executive Director of the Justice Policy Intitute

Professor James Braxton Peterson, Director of the Africana Studies Department, Lehigh University

Published on July 01, 2011 06:25

June 29, 2011

Test Driven School Reform and Disengaging Working Class Youth

Filling In Bubbles: Test Driven School Reform and Disengaging Working Class Youth by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

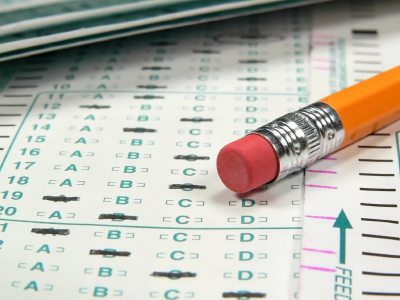

If I was going to figure out a plan to get working class youth to disengage from school, here would be my major components. First, I would make students sit at their desks all day and force them to constantly memorize materials to prepare for tests. Second, I would take away recess and eliminate gym. Third, I would cut out arts projects and hands on science experiments. Fourth, I would limit the number of school trips. Fifth, I would take away extracurricular activities like bands, and dance teams and talent shows and reduce the number of athletic teams, so that student's energies could be exclusively concentrated on strictly academic tasks.

But wait a minute, isn't that exactly what the dominant Education Reform movement in the United States is doing, from Secretary of Education Arne Duncan on down. Aren't policy makers forcing schools to add more and more standardized tests and threatening teachers and principals with mass firings if their scores on those tests don't go up, with the results that anything that isn't test driven is eliminated from the school culture?

Yes that's what's going on in education, all across the country. Starting with No Child Left Behind and continuing through Race to the Top, we are hell bent on making students from working class and poor families economically competitive with their wealthier peers by increasing their test scores and improving their graduation rates. And the way to do that, we believe, is to make them devote more and more of their time to acquiring basic literacy and then translating those skills into passing standardized tests in every subject.

But in formulating this strategy, which from the outside appears to be sensible and rational, we erase the world view of the very students in whose interests claim to be acting. We treat working class students as passive recipients of a service, who will do whatever we tell them to, rather than critical thinkers, and impassioned, sometimes impulsive historical actors, who respond to school policies based on their culture, values and their sense of how those policies effect their short term and long term interests.

As someone who grew up in a tough working class neighborhood, and has worked in similar neighborhoods as a coach, community organizer and teacher, I can assure you that young people in these communities are anything but passive when it comes to how they respond to externally imposed authority. Although some children in those communities accept authority unquestioningly, many more make it a matter of pride to challenge and test adults outside their families who claim power of them and get respect from their peers for doing so. No teacher, or coach, or social worker assigned to teach "in the hood" gets a free pass from that testing, which sometimes reaches the proportions of hazing; Whatever respect you get has to be earned.

And what goes for teachers or community workers goes for schools. Most people in poor and working class neighborhoods do not see schools as working in their or their children's interests. Their own experiences with schools have often not been that positive and their attitudes of skepticism and even hostility readily transfer to their children. Overcoming that ingrained skepticism not only requires efforts by individual teachers, it requires efforts by the entire school to make students feel that it is a place where they are respected, where their voice can be heard and their culture validated, and where they can actually have some fun. The best inner city schools I know not only make sure they maintain a welcoming atmosphere, but try to create a festive one, with music and the arts being part of every public meeting, with sports events being highlighted, and where student, parent and community input is incorporated into every dimension of the school culture.

Now enter the "Era of Test Mania," with administrators and teachers panicked they will lose their jobs if they do not produce continuous results on one high stakes test after another. Forget the school being a place where student and community creativity can be validated. Every bit of time, and energy and emotion must be devoted to test prep. Students have to sit still and listen, and memorize and regurgitate large bodies of information. Time for self expression disappears. Time for physical activity is erased. The school becomes a place filled with stress and fear.

Some students will conform, and may even pass all the tests that they are given, but just as many- a good portion of them boys- will rebel, either by disrupting classes, challenging the teacher, vandalizing the school or not going to school altogether. There is no way that working class kids like I was or a lot of the kids that I coached and taught over the years, are going to sit in school and obediently memorize material if you don't give them some physical outlets, some chance to move and express themselves, and some opportunity to speak out on issues important to them.

When you are brought up to "take no …. From anyone" and stand up for yourself, you are not about to allow teachers and school administrators to humiliate you, intimidate you, and silence your rebellious spirit. In neighborhoods where respect of peers is the key to survival, where the underground economy beckons, and where many people, in the words of Big Pun "would rather sell reefer than do Pizza delivery," schools which try to discipline students, rather than engage them, will find they are in for trouble.

The vision of School Reform currently dominant in our country, where teachers and principals browbeat and harass students to pass tests in order to keep themselves from being fired, is going to blow up in our face.

And though teacher protest will be an important component of the resistance, it will be student disengagement and violence which will ultimately put this phase of Reform to rest.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on June 29, 2011 18:57

June 28, 2011

A Noose in the Locker Room: Racism Inside and Outside of the Santa Monica High School

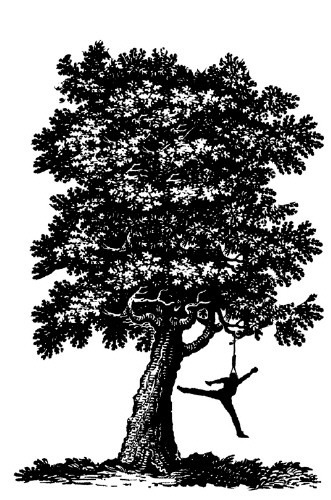

Hank Willis Thomas: "Hang Time"

Hank Willis Thomas: "Hang Time"A Noose in the Locker Room: Racism Inside and Outside of the Santa Monica High School by David J. Leonard

It was likely just another day for a Santa Monica High (CA) student when he headed to wrestling practice. Entering the locker room, things were anything but "normal." A noose was inside the room nearby a wrestling practice dummy (the specifics are unclear based on current reporting). When an African American wrestler entered the room, he was then accosted by two teammates. According to a report from the Santa Monica Daily Press , "One grabbed him in what" was "described as a 'bear hug,' while the other slipped a lock through his belt loop and connected it to a nearby locker." As they left the room, with the boy still attached to the locker, they shouted, "slave for sale."

The noose, the reference to the boy as a "slave for sale" and the attack on the African American student did little to set off alarm bells from the school administration beyond damage control. According to the above newspaper account, they failed to notify the boy's mother even while they contacted other parents connected to the wrestling team. Seemingly unconcerned about the impact of this attack on the boy, his family and the larger community of students of color at Santa Monica High School, their efforts appeared to be directed at helping (rather than punishing) and protecting the students who perpetrated these shameful acts. Some reported that at the request from school officials, pictures of the noose, for example, were erased from several student cell phones.

Disgusting, shameful, and yet another reminder of the illusion of a post-racial America, this instance is a telling reminder of the continuity of racism within twenty-first century America. The history of slavery, lynching, and racial violence stares us in the face. Yet, for some this instance tells us little about current racism. Despite the seriousness of the situation, it has received next to no media attention. In a city (Santa Monica and Los Angeles) where media has almost fixated on black-Latino tensions amongst students, it is revealing how small the media spotlight has been. Moreover, in wake of the tensions, communal problems, and the injustice directed at the Jena 6, it is troubling, to say the least, to see a school district take such a blaze approach to this hate crime (only after heightened pressure did the school district expand its response). Instead, there seems to be an attitude of confinement, an effort to isolate this incident as an aberration. Whether blaming it on athlete culture, male horseplay, or simply depicting the kids as "bad apples" who made a mistake, a portion of the reaction leaves one believing that this an isolated problem rather than symptomatic of a larger climate problem.

Tim Cuneo, the school's outgoing superintendent, offered the predicable rhetoric about the school's commitment "diversity" and promoting "a positive environment." Yet, the rhetorical references to "horseplay," "bullying," and "harassment" with "racial overtones" leaves one wondering if the school does not have the historic understanding of racial violence – the historic meaning of the noose as an instrument of racialized terror. At the same time, the focus on the individual participants and the treatment of the incident as isolated erases the bigger issues here.

One has to look no further than the comment section on Santa Monica Daily Press report to understand the larger issues in place. In an effort to counteract the narrative that depicts Santa Monica as a racial utopia where a couple kids made poor decisions, comments continually reference the immense double standards in the treatment of students of color and white students, tracking, and the differential levels of privilege and power afforded to students. One post makes this clear

Now I'm not at all condoning what happened back in 2006, but it's interesting to see the different reactions when the perpetrators are White and not another minority. The incident is swept under the rug and the students are let off with a slap on the wrist. Those two students should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. There is NO reason why they should still be allowed to attend SAMOHI classes. We, the Black and Latino community of Santa Monica, are used to this second class citizen treatment by the SMMUSD and the city. The school district, the police department, and the city tried their hardest to eliminate the one member of the school board that stands up for our interests and works tirelessly to prevent incidents such as this.

Another comment also speaks to the broader issues in play and the treatment of students of color as 2nd class citizens, especially in comparison to white students who reap privilege each and every day:

Let's talk about what's really going on at Samohi, how about the Cambridge 3, 3 white girls get caught drinking and the board re-writes the no tolerance rule for them and they are allowed to participate in all senior activities. If a white parent screams about a cell phone that's been taken by a teacher 4 times because their child talks or text message in class the phone is given back no consequence. We get it rules only apply to students of color.

These powerful comments speak not only to the anger about this particular hate crime, but the systemic racism within the Santa Monica School District. A 2010 report from the Santa Monica Daily Press found that "minority students in the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District continued to account for a disproportionate percentage of suspensions." For example, at John Adams Middle School African Americans constituted 11 percent of the study body, but accounted for 25 percent of suspensions; Latinos were 52 percent of the school's population yet 64 percent of those suspended. Compare these numbers of whites, who represented 34 percent of school's student body, but only 11 percent of those suspended. Oscar de la Torre, a member of the School Board, described the report as evidence of the continued relevance of institutional racism. It shows yet again how "race and ethnicity are factors in the degree of punishment and also the degree of consequences for the same infractions."

The noose, and the attack on this student are two more examples of the persistence of institutional racism. Likewise, the inequality in terms of access to advanced placement classes is another example of the persistence of racism at a structural level. A 2007 report from the Santa Monica Daily Press highlighted disparities between black and Latino students and white students in both enrollment and proficiency in advanced placement courses. As such, the horrific treatment of this student is not only a symptom of a larger issue at the high school, in the District, and within the community, but an outgrowth of a culture that empowers white students all while treating students of color as second-class citizens.

While some have argued that this should have been a teachable for the students involved, teaching should never come at the expense of the others. It can be a moment of clarity, where we see the broader problems here and throughout the country. Santa Monica High is not alone here as all of these issues are national problems. Teaching Tolerance found that each and every year, 1:4 students reported falling victim to racial or ethnic mistreatment; same study found that 70% of female students have experienced sexual harassment with 75% of gay students reporting anti-gay slurs and treatment.

Racial bias and discrimination is equally evident in the application of suspension policies. A study of New York schools found that while black children represent one-third of students, they account for over 50% of those suspended. "A national survey of high school students found that the number of students reporting the presence of security guards and/r police officers in schools increased from 54 percent in 1999 to 70 percent in 2003" (Sullivan 2007, p. 7). According to a study by the Applied Research Center (Oakland, California), black students have disproportionately endured the impact of zero tolerance policies. The study "reported higher than expected rates of suspension and expulsion for black students in all 15 major American cities studied" (Skiba 2000, p. 12). Even though white youth are more likely have used cocaine (7 times), heroin (7 times) and methamphetamine (6 times); even though white youth ages 12-17 are more likely to have sold drugs; even though white students are far more likely to whites to bring a weapon to school; blacks students face the daily repercussion in the suspension-schooling complex (Wise 2000).

In thinking about the varied treatment experienced by today's students -- to suspend or not (eventually the two boys were suspended in this case); to call the police or not (only after the boy filed a complaint did the police begin an investigation ); to treat an incident as a "teachable moment" or a moment of incarceration; or the ability to walk into a locker room without being subjected to racism – we see a school and a school district with two sets of rules, one for its white students and another for those treated each and every day as second-class citizens. What happened on May 4 was yet another example. It is no wonder that Jeannie Oakes, <!-- /* Font Definitions */@font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}@page Section1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;}div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style><span style="font-family: Cambria; font-size: 12.0pt; mso-ansi-language: EN-US; mso-ascii-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family: "Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font: minor-bidi; mso-fareast-font-family: Cambria; mso-fareast-language: EN-US; mso-fareast-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-hansi-theme-font: minor-latin;">in Racial & Ethnic Data in Schooling</span><span style="font-family: Cambria; font-size: 12.0pt; mso-ansi-language: EN-US; mso-ascii-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family: "Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font: minor-bidi; mso-fareast-font-family: Cambria; mso-fareast-language: EN-US; mso-fareast-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-hansi-theme-font: minor-latin;"></span><span style="font-family: Cambria; font-size: 12.0pt; mso-ansi-language: EN-US; mso-ascii-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family: "Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font: minor-bidi; mso-fareast-font-family: Cambria; mso-fareast-language: EN-US; mso-fareast-theme-font: minor-latin; mso-hansi-theme-font: minor-latin;"></span>, identified Santa Monica High School as a place of "two schools," one where college is likely, where advanced placement courses are commonplace, and where respect is a given to those white in attendance; the other is the school that houses black and brown youth. Unfortunately, when these two "schools" collided on this very day, the power and privilege of the one school once again illustrated the second-class citizenship that defines the other school.</div><div style="text-align: justify;"></div><div style="text-align: justify;">***</div><div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: x-small;"></span></div><div style="text-align: justify;"></div><div style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: x-small;"><span>David J. Leonard is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of <b>Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema</b> and the forthcoming <b>After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop</b> (SUNY Press). Leonard blogs @ <a href="http://notsuris.wordpress.com/"&... Tsuris</b></a></span></span></div><div class="blogger-post-footer"><img width='1' height='1' src='https://blogger.googleusercontent.com...' alt='' /></div>

Published on June 28, 2011 11:40

June 27, 2011

Tony Cox: Helping Black Men Raise Failing Grades

Tell Me More w/Michel Martin | NPR

Helping Black Men Raise Failing Gradesby Tony Cox

Some thoughts about school and the struggles black kids face. Lots of folks with lots of experience have lots of opinions about what to do to better educate young African-American males. Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates recently offered yet another glimpse into the issue, suggesting in a piece for the website The Root that the need is dire, which of course it is.

But for many of us in education — and to my mind that includes parents, family and friends — the problem is more than knowing what's needed. It's knowing how to get it done and make it work, how to get young African-American men not only interested but engaged in learning, and enjoying rather than dreading the journey. That requires a lot of commitment from them and from us, and there are no shortcuts.

Besides my work here at NPR, I am a tenured professor in broadcast journalism at California State University, Los Angeles. I primarily teach writing, and it troubles me to no end to see young black men struggle in my classes because they can't or don't see the value of an education and the effort required to obtain one. Records show black male students badly lagging in their graduation rates from colleges and universities. When we see them on campus, they often dress differently, speak differently, have different expectations, and in the classroom can sometimes be difficult to reach.

Published on June 27, 2011 15:12

Denver Bronco David Bruton Teachers Math & Science During Lockout

Tell Me More | NPR w/Michel Martin

As the NFL tries working through its lockout, one professional football player decided to teach youth from grades one through 12. In April, Denver Broncos safety David Bruton became a substitute social studies and math teacher at Jane Chance Elementary School and Miamisburg High School (his alma mater) in Ohio.

Bruton says he got the idea from his high school coach and teachers. Why did they think he was teacher material? Bruton says maybe it was because he performed well during his own high school and college years, and he had what it took to be a role model. His patience and persistence also helps, he says.

Published on June 27, 2011 12:21

June 26, 2011

Jimmer Fredette and the Fantasy of Reverse Discrimination

The Great White Hope?

Historic Amnesia:

Jimmer Fredette and the Fantasy of Reverse Discrimination

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackMan

The Great White Hope?

Historic Amnesia:

Jimmer Fredette and the Fantasy of Reverse Discrimination

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackManThe 2011 draft brought cheers and optimism from teams across the nation. From the Cavs to Timberwolves, the NBA draft always provides a glimmer of hope for several of the NBA's habitual losers. The celebratory tone was not limited to fans who concluded that this year's player was the final piece of the puzzle, but found its way to those who saw hope beyond wins and losses with the entry of Jimmer Fredette into the NBA. Fredette, the leading scorer during the 2011 college basketball, was a highly honored point guard from Brigham Young University, having won Wooden Award, the Adolph Rupp Trophy, the Naismith Award, and the Oscar Robertson Trophy. Notwithstanding, Fredette has been positioned as a "great white hope," a tribute to perseverance and fortitude who has worked to overcome his physical limitations and their stereotypes concerning white players.

In " Fredette out to break NBA stereotypes ," Ian O'Connor joins the celebration, ostensibly calling his entry into the NBA as a game changer. "In living color, Jimmer Fredette turned out to be a study in black and white, a prospect whose vertical leap was most valuable when he hurdled a stubborn stereotype and landed in the lottery of the NBA draft," wrote O'Connor. Acknowledging his potential on the court, O'Connor focuses on the opportunities that transcend points, assists, and even wins/loses. "He could help change the unfortunate language of the NBA draft, one littered with racial code words that need to die a sudden and painful death." His movement in the NBA potentially represents "a great moment for all right-minded fans, black and white, if it helps change the unfortunate language of sports."

The argument that stereotypes about white basketball players represents an obstacle is nothing new. Yet, O'Connor takes the discussion to a new level, using a player who was drafted 10th overall (not to mention one who received endless media praise; every major college award) as an example of anti-white bias. In other words, what has he lost because of the stated stereotype (s/o Kenneth Carroll)? The 10th pick? Millions of dollars? Despite concerns about his defense and speed, not to mention shot selection, the level of competition he played against during college, whether or not he has a position in the NBA (point guard size with scoring guard mentality), and how has stats were inflated by the number of shots taken, he still was taken 10th in the draft. Stereotype or not, opportunities are abound for Jimmer Fredette.

While certainly guilty of hyperbole that imagines whiteness as a discriminated minority within the NBA, O'Connor's greatest sin is his comparison between Jimmer and Doug Williams, the great NFL quarterback. To highlight his argument about racial stereotypes and the obstacles faced by athletes, O'Connor links the story of Fredette to the struggles that Williams endured as a black quarterback. "It's unfortunate that some people, whether it's the media or outside forces, will always look at athletes from a black and white standpoint," noted Doug Williams in the article. "The man who helped crush the vile stereotype that African-Americans couldn't make for winning quarterbacks. When I was playing football, an African-American quarterback didn't have as much time to prove he can play. It's unfortunate that [Fredette] might have to deal with the same thing in the NBA."

O'Connor was not alone in the deployment of a narrative fantasy depicting white as the true victim of racism in today's sports world. Other then seized upon the linkages and Williams' comments about Fredette in an effort to lament reverse discrimination faced by white athletes.

O'Connor's historic erasure is troubling to say the least. The structurally-based "pig skin" ceiling experienced by Doug Williams and countless other African American quarterbacks has its origins in white supremacist ideology that has historically denied intelligence, leadership qualities, and other skills required for the quarterback position to African Americans. According to N. Jeremi Duru, "Quarterbacks of color were rare for the longest time, and still remain statistically rare. Centers of color, middle linebacker of color, the quote unquote 'thinking positions' have tended to be relatively homogenous and excluded people of color, and head coaching position as well."

This same sort of racist logic also played out in justifying segregation in the military, exclusion from institutions of higher learning, and denial of the rights of citizenship. The exclusion of African Americans from the position of quarterback "has implications off the football field. The discrimination dynamic that surrounds the issue of Black leadership on the turf reflects the greater racism that shapes our entire society," writes Dave Zirin . In other words, the ideology that questions black intelligence and leadership is foundation to American racial ideology and therefore has a longstanding history inside and outside of the realm of football.

The same history cannot be pointed to when discussing Jimmer Fredette. It is hard to argue that Jimmer, a player who despite hoisting 20.7 shots per game, who is often lauded as a team player, unselfish, and someone who doesn't dominate the ball (he has been positioned as the anti-Kobe/AI/Baller of the new school – Thabiti Lewis ), suffers at the hands of some reversed racist conspiracy. His whiteness represents a privilege and a commodity.

At the same time, the stereotypes that play out within the media narrative is not the result of some anti-white bias (or reverse racism) but is a manifestation of white supremacist discourses (anti-black racism) that tends to construct whiteness (in opposition to blackness) as intelligence, the cerebral, the civilized, etc., qualities that are desirable in every capacity. So whereas we can link the discrimination felt by Doug Williams to high rates of unemployment or incarceration, we cannot link the purported stereotype (that confined Jimmer to the 10th pick) to denied opportunities to whites outside of the sports realm.

In fact, the celebration of Jimmer's intelligence, work ethic, and dedication to team – his whiteness within the dominant imagination – demonstrates why black unemployment is nearly twice that of whites. Jimmer and his white peers in fact continue to reap the benefits/wages of whiteness each and every day, a fact erased by the fantasies that depict Jimmer as yet another white male suffering at the hands of America's new racial order.

A 2011 study from Tufts University and Harvard University found that despite different views about race, both blacks and whites agree that anti-black racism has decreased during the last six decades. More importantly, these same white respondents identify anti-white racism as a significant problem, one that in 2000 outpaced anti-black racism. Jenee Desmond-Harris in " White People Face the Worst Racism?" describes the study's conclusions as follows:

"These data are the first to demonstrate that not only do whites think more progress has been made toward equality than do blacks, but whites also now believe that this progress is linked to a new inequality -- at their expense," note Norton and Sommers. Whites see racial equality as a zero sum game, in which gains for one group mean losses for the other."

The narrative that imagines racial progress as not only eroding anti-black racism but also reversing the playing field is commonplace, evident in this study and in writings about Jimmer Fredette. Fredette is represented as a white person who suffers because of discrimination, that same sort of treatment that African Americans USE to endure. He is imagined as someone who must deal with PREJDUICE and STEREOTYPES, the same sort of racism that players like Doug Williams USE to have to deal with it. He is celebrated as someone who in spite of obstacles and bias is successful, providing legitimacy to the neoliberal bootstrap mantra "If they made it why can't you?"

The historic erasure is not surprising and illustrates how sports exist as a national playground to rethink and reimagine ongoing histories. Whereas Williams faced discrimination based in longstanding white supremacist ideology that restricted his employment (and that of millions of others), Jimmer cannot say the same thing. Whereas Doug Williams and countless other black quarterbacks were criticized for their lack of intelligence, poor work ethic, questionable decision-making, and leadership skills, Jimmer has faced questions about his speed and willingness to play defense, the second which has nothing to do with racial stereotypes. Whereas Doug Williams found success in spite of the "pig-skin ceiling" because of collective action and the revolt of the black athlete, the NBA opened its arms to Jimmer Fredette with little apprehension, excited about how he can change the NBA – how he is a "breath of fresh air." Yes, whiteness matters and Jimmer Fredette is no Doug Williams.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard blogs @ No Tsuris

Published on June 26, 2011 09:32

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.