Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1071

July 18, 2011

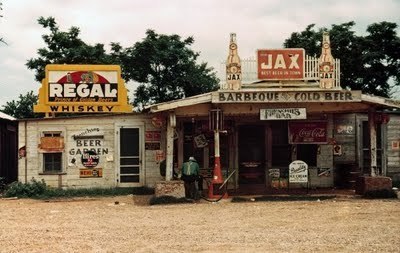

The Chitlin' Circuit And The Road To Rock And Roll

NPR (WBUR)

On-Point with Tom Ashbrook

The Chitlin' Circuit And The Road To Rock And Roll

The amazing story of African-America's "Chitlin Circuit," and the road to rock and roll.

Across the country in segregated 20th century America, there was a world where black musicians soared even when the color line held them down.

It was Beale Street in Memphis, the Bronze Peacock Dinner and Dance Club in Houston, an old tobacco barn in South Carolina, where the music went all night long. It was the Chitlin' Circuit.

Grand ballrooms and steamy juke joints. The venues where African-Americans were free to play and be. Where, says my guest today, rock was born.

This hour On Point: a new history of the Chitlin' Circuit..

Guests:

Preston Lauterbach, the author of The Chitlin' Circuit and the Road to Rock 'N Roll

Bobby Rush, a musician, composer and singer.

Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African-American studies at Duke University. Listen

Published on July 18, 2011 13:13

TDK Interview: 9th Wonder

9th Wonder talks with TDK about his career and early days with cassettes and Boom-boxes.

Published on July 18, 2011 10:49

My First and Most Improbable Emissary into Black Music and Black Culture

This Magic Moment: My First and Most Improbable Emissary into Black Music and Black Culture by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackman

David Leonard's recent essay "White Boy Remixed: Whiteness and Teaching Race," got me thinking about my own convoluted evolution as a white scholar of Black Studies, and in particular about an important figure in my life whose story was left out of my book White Boy: A Memoir.

His name was Ron English and he was a basketball counselor at a "progressive" but virtually all white summer camp I went to for three years, beginning 1959, Camp Taconic in Hinsdale Massachusetts.

At first glance, Ron seemed to be a most unlikely emissary for Black culture (a term that virtually no one, certainly, no one I knew used in those pre-Black Power years). Ron was 6'7" tall, all arms and legs, with a brownish blond crew cut atop what, for someone his size, seemed to a very small head. He spoke with a Midwestern twang and seemed out of place among the mostly Jewish, leftwing campers, who came from sophisticated, highly educated families who lived in the Upper West Side of Manhattan or wealthy suburbs, that is until he moved.

With the exception of Connie Hawkins, Roger Brown and Billie Cunningham, all of whom played high school basketball in Brooklyn- in the same division-when I was growing up, Ron English was the greatest athlete I had ever seen in my life. He moved with catlike grace and excelled in every sport he tried his hand at. Not only was he an amazing basketball player, who ended up as the last cut of the Kansas City team in the American Basketball Association, he could hit a golf ball 300 yards and was the best softball or baseball player I had ever competed against.

But it was not Ron's athletic feats which left the biggest impression on me, it was his encyclopedic knowledge of rock and roll and rhythm and blues, which he displayed three times a week when he DJ'd the dances that Camp Taconic held in the evenings. For some reason, this progressive camp, which had folk singing every morning, sponsored evening dances 3 times a week for all campers over 10, where boys and girls could dance to the latest rock and roll hits, slow or fast, and if the spirit moved them "make out" for up to 5 minutes after the dance behind the archery range. As a 13 year old just reaching puberty, I felt that I had died and gone to heaven and I hoped against hope that some female camper would feel the same way I did and join me on the archery range.

Those moments, alas, proved few and far between, since before I went to college and grew a goatee, I had a face "only a mother could love." But while waiting in vain for "This Magic Moment" ( The Drifters) on the dance floor, I was utterly entranced by the music Ron was playing and the commentary he gave that accompanied it. While Ron would play a broad spectrum of rock and roll hits, including artists like Elvis and the Everly Brothers, it was clear that his real love was for African American rhythm and blues artists, particularly those from the Midwest.

He would grow particularly reverential when putting on Jerry Butler's "Your Precious Love," which he described as the greatest slow dance song of all time, and regaled us with stories of seeing Jerry Butler live. He had an equally high opinion of Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, whom he had also seen live, and made sure that we got to exercise our lindy hopping skills to songs like "A Quarter to Three" and " A Thrill Upon the Hill." He had a special feeling for the Five Satins "In the Still of the Night" which he played at every dance he ever DJ'd, and which many of us tried to imitate in harmony when we went back to our bunks, especially those of us who missed out on the make out sessions on the archery range.

For me, an impressionable 13 year old from a Brooklyn working class neighborhood, surrounded by campers much wealthier than I was, longing for a romance that rarely came, Ron turned what could have been times of disappointment into times of incredible excitement. Ron made it seem that these songs, virtually all produced by African American artists, were almost holy artifacts, not only filled with beauty, but with a capacity to transport people beyond the everyday cares of life and make them bond with one another in love and friendship. Even before I met Ron, this music had stirred me; I had started listening to rock and roll at age 11, and had always had special feeling for urban harmonic songs like " Why Do Fools Fall in Love" ( Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers) and "Just Two Kinds of People in the World" ( Little Anthony and the Imperials).

But now someone ten years older than men, who I admired greatly, was giving me an explanation, and a justification, for the feelings I had when heard those songs, and investing those feelings with an air of romance.

That this man was a white Midwesterner, playing and commenting on what was basically Black music in front of an all white audience of Jewish campers, represented an irony that escaped me at the time. I only knew that this music made me feel better than anything I had ever heard in my life, not only inspiring me with longings for of adolescent sex and romantic love, but making me feel I was part of a sacred community of young people bonded by music that was at times, more beautiful than anything I had ever heard in my life.

I was not yet a civil rights protester. I would not attend my first demonstration, at Ebingers Bakery in Brooklyn, until the Spring of 1962. My studies of Black history were at least five years down the road. The relationship with a Black woman that made me the person I am today was still in the distant future.

But something was taking place at those dances at Camp Taconic that would mark me for life. I cannot, to this day, hear Jerry Butler's "Your Precious Love" without feeling chills run through me, and without repeating, to everyone around me, Ron English's pronouncement that this was "the greatest slow dance song of all time"

A white Midwestern basketball star, DJ'ing at all white dances at a progressive Jewish camp, had made one white boy, and possibly many others, fall in love with Black music, and become open to a connection with Black culture that would remain an integral part of his life.

Appropriation? Certainly. Exploitation. Quite possibly. But maybe something else was going on here, albeit unconsciously. Nation Building. Creating a society where Black people's labor and music and struggle were the building blocks of a new civilization that might replace, though only with great pain and conflict, the White Supremacist society that we had all been born into.

An improbable scenario? For sure. But when I put on "Soul Town" on my XM radio driving to work each morning and hear the songs Ron played, I think nothing is impossible.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on July 18, 2011 10:27

July 16, 2011

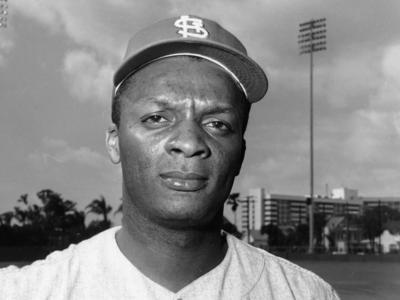

HBO's The Curious Case Of Curt Flood

Saturday Edition

The Way It Is: HBO's The Curious Case Of Curt Flood by Nasir Muhammad & Stephane Dunn | special to NewBlackMan

HBO's project was long overdue and an exciting prospect – an overview of Curt Flood's life and exploration of the historic stand he launched against Major League Baseball's reserve clause in 1969. While the documentary introduces Flood and his infamous suit against baseball to those who are unfamiliar and tries to fill in some blanks about what led to it, The Curious Case of Curt Flood condenses a complex personality and history so much that it distorts some essential details about Flood's long struggle for players' rights in MLB. It also commits a serious error in steering clear from dealing with the 'elephant' that remains in the room when it comes to Curt Flood's legacy in MLB history: Despite free agency's defining role in contemporary MLB, the league is still uneasy about Curt Flood's challenge to the hierarchy of America's Pastime - so uneasy that the respect that Flood really deserves as a player and a trailblazer in the Civil Rights struggles of the time continues to be denied.

MLB's measure of legacy is integrally tied to election into hallowed historic ground, the Baseball Hall of Fame. So far, Flood has not been so honored. Through a select array of photographs and video clips that offer a close-up primarily of Flood at his worst, the documentary mostly presents a strikingly sad portrait of a man headed for self-destruction. Curious Case raises the issue of Flood's legacy but doesn't really go there, preferring instead to overshadow and fill in the more significant aspects of Flood's challenge to the power status quo with sensationalist gossip about his legitimacy as an artist, financial troubles, and a demon [alcoholism] he shared with a long line of sports greats, including Babe Ruth.

The problem with HBO's effort begins with it's obvious over reliance on one dominant source, Brad Snyder and his book on Curt Flood, A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood's Fight For Free Agency. What's curious is the documentary's neglect of Flood's own thoughtful examination of his journey to suing MLB, The Way It Is (1970), an autobiography published during the time period encompassing his suit. While the documentary smatters in Flood quotes from interviews and some of his most frequently used statements, Flood's very detailed take on his experiences and opinions about the inner workings of MLB in The Way It Is hardly appears and the book is generally invisible save for widow Judy Flood's liberal borrowing from the text to inform some of her comments.

Much is made of the '68 World Series loss attributed to Flood; Snyder offers this and Flood's demand for more money as Busch's main motivation. However, Busch's anger with his "favorite" player was most certainly tied as well to Curt acting in concert with other players in the MLB Players Association in '69 against owners efforts to in his words "sever the traditional link between the pension fund" and money from radio and television. According to Flood, the players refused to sign their contracts until the owners agreed to better pensions for players and key Cardinal players, among them Lou Brock, Tim McCarver, Bob Gibson, and Flood demanded substantial salary increases. This incensed Busch, who blasted his players at a public meeting with media present.

Toward its conclusion, the documentary chooses to focus heavily on Flood's personal downward spiral into alcoholism and the tragic portrait he presented of his former self. It ends by concentrating on his journey back into living a functional life and fashions a sort of triumphant recognition of his historic stand before his death from lung cancer in 1997. The documentary offers those watching who don't know much about Flood a deceptive reason to feel moved and ultimately good about the seeming respect it suggests he finally received. Yet, the absence of two of the greatest living legendary baseball players, Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, and the current commissioner of MLB suggests the truth. The scorching review of sportswriter Stan Horch, who was interviewed for the documentary but whose insights do not appear at all, isn't too off base in summing up the E' Hollywood like treatment of Flood:

The courageous athlete who dared to challenge an unfair system is depicted as an alcoholic, a womanizer, a woeful husband, a dreadful father, a lousy businessman and a fraud who never really painted those portraits he churned out that enhanced his image as an artist . . . .In the history of warts-and-all biographies, this one slithers near the top of the list.

Curt Flood's historic Christmas Eve letter to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn is in the Baseball Hall of Fame Museum, but Flood is not in the Hall of Fame. This fall, the Baseball Writers Association has the power to select Flood as one of ten players to appear on the Golden Era ballot where that sixteen member committee can finally genuinely welcome Flood back into MLB. The documentary raises the issue of Flood's legacy but it shies away from probing two vital questions critical to a film presuming to treat this major chapter in Flood's and baseball's history: Is MLB ready to reconcile its important history with Curt Flood and do the right thing? Or will the silent punishment of Curt Flood be allowed to continue?

Published on July 16, 2011 07:05

July 13, 2011

White Boy Remixed: Whiteness and Teaching Race

White Boy Remixed: Whiteness and Teaching Race by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackMan

This summer I have dedicated to reading that stack of books I have been wanting to read. The 4th installment (I will write about the other three books on my blog) was Mark Naison's memoir – White Boy. Naison, a professor of African American Studies at Fordham University, chronicles his personal, political and academic journey, responding to those who have ubiquitously asked how he as a white man became a professor of African American Studies. With a tremendous amount of honesty, openness, complexity, and vulnerability, Naison explores his own history as a teacher, activists, and source of community empowerment. While the book chronicles a powerful story of the 1960s – the anti-war movement, the Panthers, Columbia, identity politics – it is a story of a dynamic man whose life and insights teach us just as he has taught his students for several decades. In telling the story of the "white African American Studies professors, Naison offers a narrative that highlights how whiteness matters but how it does not define or over-determine the arch of his life or career. It is a story that resonates with me on so many levels, leading me to want to share my own story.

Like Mark Naison, I have been consistently asked about my entry into Ethnic Studies. In my first class at Washington State University, I had a student that constantly wanted to know my story. The student could not understand why this White guy was teaching African American film – what had lead me to be me – In the course of the class, he asked "How I can to be the Eminem of Ethnic Studies?" While the class oohed and aahed, some thinking it was a slight against me and others thinking it was a point of celebration, I saw it as a good question, one that could lead (and did) into some important conversations. Another day I had a group of students who came to my office asking me to settle a bet about how I came to Ethnic Studies, each having a different theory – (a) I grew up in the Black community; (b) I had a Black girlfriend or a Black wife who had taught and encouraged me to learn; (c) I was just down. In fact, I have been asked several times if I have a Black girlfriend who educated me about blackness, taught me to be committed and down, and pushed me down my educational and career path.

On another level, I have been asked if I am a "culture vulture," in the tradition of Elvis, in that I am "taking" and "impersonating" something that I am not, in my educational and professional choices. I have also experienced much celebration being a white guy in ethnic studies. Most often such comments reflect desires for colorblindness as a presumed end goal; that is, my presence in Ethnic Studies supposedly embodies the fulfillment of King's dream or a sign of progress. A student once sent me an e-mail that said that world was changing racially, for the better, because the best rapper was white, best golfer is black, best basketball player was Asian ...and their ethnic studies teacher was white. Not to be outdone, a student cited my presence in Ethnic Studies as evidence of colorblindness, to discount our discussions about racism and inequality. However, what the student failed to see is whether or not their teacher was White, or the president is Black, racism remains a constant.

I am certainly defined by my whiteness, whether teaching ethnic studies or driving through Colfax; yet my relationship to Ethnic Studies, social justice struggles, my scholarship, my pedagogy, my ideology, my gaze upon the world, and my understanding of racism/privilege/inequality is not overly determined by a monolithic white identity formation. As Bakari Kitwana argues in Why White Kids Love Hip Hop, "Each Person has a unique story that brought him or her to hip-hop. Looking at the micro reasons as well as the macro ones helps us make sense of a contemporary hip-hop scene in which a new generation is affected by America's racial history and in the process is constructing a new politics." In others words, my arrival to and place within the field of Ethnic Studies (or a larger racialized discursive field) reflects a myriad of factors and experiences, ones that are neither defined exclusively by nor immune from the realities of whiteness, racism, and contemporary racial politics.

I grew up in Los Angeles in a middle-class family that spent most of its income on schools, not so much because of concerns of "safety" or even the quality of education available in the public school system. I went to an elementary school founded by Hollywood Communists, including Charlie Chaplin. During my life, I have never gone to school where we did not call our teachers by their first name; I did not receive "grades" until the 9th grade. More instructive, both detention and the pledge of allegiance were completely foreign concepts to me until high school. This educational background clearly established a foundation but this only tells part of the story.

I was also somewhat typical of many white kids growing up in the 1980s and 1990s. Often times I could be found rocking my Malcolm X hat, cross-colors shorts, and historically Black college sweatshirt. I sagged my pants, wore my starter jackets and had a swagger that I thought embodied my sense of bravado. For a couple days, I even had my hair braided, quickly removing them after I was serenaded with "Kris will make you jump" during a pick-up basketball game. Not surprisingly, I was never conscious of the process of appropriation, nor was I initially conscience of the inherent power/violence in "eating the other." I was like so many kids that we see on campus, in that I saw my performative hip-hop identity as both "me being me," and also as something good. I think Bill Yousman best describes my initial appropriation of hip-hop culture within my own imagination in the following terms:

White youth adoption of Black Cultural forms in the 21rst century is also a performance, one that allows Whites to contain their fears and animosities towards Blacks through rituals not of ridicule, as in previous eras, but of adoration. Thus, although the motives behind their performance may initially appear to be different, the act is still a manifestation of White Supremacy, albeit a white supremacy that is in crisis and disarray, rife with confusion and contradiction (In Kitwana 103).

While he emphasizes how fascination and fetishization often coexists and fosters white youth resistance to anti-racist activism, through either actual opposition or simple erasure, denial and ignorance about racism, Bakari Kitwana celebrates the transformative possibilities in hip-hop: "My belief is that rather than being resistant, many white hip-hop kids have yet to realize that is up to them to create such anti-racist programs." More specifically, he writes how hip-hop and spaces of hip-hop have provided a new arena of public space where a new racial politics has the potential to form. At a certain level, my own experiences with hip-hop mirrors the optimism offered by Kitwana. For me, hip-hop was a place of entry to social justice and anti-racist scholarship, teaching, and practice.

Whereas rock n' roll seemed to be central to Mark Naison's political, educational, and personal development, hip-hop provided a powerful form of socialization for me. While I could talk about a number of examples, from how listening to NWA or Public Enemy pushed me to examine the history of policing within communities of color or how Arrested Development forced me to contemplate the realities of privilege, poverty, and homelessness in the United States, one song that inspired me to become a teacher was KRS One's "You Must Learn." It introduced me to an unknown history that I came to realize was erased from dominant historical memory. It ultimately led me into library, encouraging me to question my schooling and those "self evident truths." Yet, it was not just the music.

There are countless other experiences, from my short time at University of Oregon and my undergraduate and graduate experiences at UCSB and UCB, to the Los Angeles uprising, that shaped not only my livelong passions but my identity and ethos. More than any other experience, the reason I am a white professor of ethnic studies stems from the influences of and mentorship I have received since an undergraduate. I have benefited tremendously from teachers, peers, and students who did not discourage or shun me (what is often assumed to the case), but instead educated, nurtured, challenged, and inspired me.

Kofi Buenor Hadjor, an instructor of black studies at UCSB, did it all. Beyond the classroom Kofi was a mentor. We used to sit and talk about the O.J. Simpson trial, police brutality, US policy toward Africa; his time with Kwame Nkrumah, Mao and Dubois; his thoughts about health care inside the U.S. and herbalism; we would talk religion, family, gender; he taught about humility and mentorship, compassion and community. While my parents planted the seeded, he molded me into the person, the professor, the scholar, and the advocate of social justice that I am today. He demanded in me respect for history and for books; he fostered in me a passion for sharing knowledge; he required of me self-critique whether in class or helping out around his house.

One day, Kofi, who was recovering from a stroke, asked me to go buy some fruit from the store. When I returned from the store with apples, bananas and pears, he took a moment to highlight the politics and privileges embodied in fruit. To him, these were "first world fruits," and he wanted a mango or a papaya. I ultimately got him that mango, only then realizing I had no idea how to cut this fruit. In this instance, I learned how about my own privileges blinded me to the experiences of others; he taught me so much about myself. More than the specifics, he taught me the power of learning and teaching. Some 15 years later, I have so many vivid memories about his lectures, our private conversations, and the many lessons he taught me.

I just wish I was able to sit in one more of his classes or simply sit in his living room so we could talk one more time. Mark Naison's book reminded me of Kofi influence and hopefully one day I will be able to visit Dr. Naison's class because it is clear that he is able to inspire just like my mentor Kofi.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on July 13, 2011 11:15

July 12, 2011

From Ghana To Brooklyn: Learning From Hip-Hop

NPR Weekend Edition

From Ghana To Brooklyn: Learning From Hip-Hop by Frannie Kelley

July 10, 2011

Blitz The Ambassador is a rapper and teacher. He grew up in Africa, moved to Ohio for college and now teaches songwriting at schools in New York City.

He was born Samuel Bazawule, and he turned 10 in 1992. He was living in Accra, the capital of Ghana, and there was only one thing he wanted: tapes of rap music from the U.S.

"It was hip-hop," he says. "You didn't even have to ask. It was almost cultish. We just spent all our time making tapes. So, when people were traveling, they knew not to get anything but hip-hop."

Groups like A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul and the Jungle Brothers were beloved in Accra for talking about Africa in their rhymes — and dressing the part.

"There were these guys wearing Africa medallions and all these dashikis in really cool colors," Bazawule says. "To us it was like, 'Wow, man, they know we exist.' It was just so cool that these cool guys recognized us."

But his all time favorite hip-hop group was Public Enemy. "Public Enemy was the ultimate edge to me," he says. Twenty years later, Chuck D makes an appearance on Blitz's new album Native Sun.

Blitz didn't move to the U.S. just to become a rapper. He came for school. In his family, he says, "like most African families, it's really about education, having those jobs that are pretty standard — the doctor, the lawyer."

Blitz went to Kent State University and graduated with a business degree. But the whole time he was in Ohio, just like in Accra, he was listening to hip-hop, learning from his big three: Rakim, KRS-One and, of course, Chuck D.

"One thing I have to tell people, and it's very important: Rap is something I learned," Blitz says. "I learned every piece of it. I wasn't born here where it's, like, natural, it just seeps into your lifestyle. This is something that was studied."

Now, when he's not recording or touring, Blitz is a substitute teacher who uses hip-hop in the classroom. He says he realized hip-hop could be an educational tool when he was still in school.

Listen HERE

Published on July 12, 2011 07:43

Work-in-Progress | Close Ties: Tying On A New Tradition (film)

Close Ties: Tying On A New Tradition A Documentary project in New Orleans, LA by Park Triangle Productions

Close Ties: Tying on a New Tradition provides an intimate look at a rites of passage ceremony that connects teenage boys with male role models. The "Tie Tying ceremony" held at New Orleans barbershop, "Mr. Chill's First Class Cuts", was created by Dr. Andre Perry and Wilbert "Chill" Wilson as a way to strengthen communities struggling with crime, poverty and alarming high school drop out rates. Cultural traditions have been the cornerstone of African American communities for centuries. Close Ties examines the impact of this new tradition and shows us how tying a necktie --- an act associated with men who embody professionalism and prestige --- can inspire high school boys to commit to a life of achievement and success.

During the event, the boys participate in a tie-tying demonstration, where role models from around the city instruct the youngsters on how to create distinguishing knots with their neckwear. Each of the boys also receives the opportunity to get professional grooming with a haircut and a shoe-shine. The final component of the event is one-on-one mentorship that each student receives from a male role model from the community. The youth participating in this tie-tying ceremony are boys selected from several schools in New Orleans.

Close Ties documents the mentors and the youth during and after the ceremony, where we see the men encourage and support the boys' academic and career endeavors. The development of these mentoring relationships creates a lasting impact, one felt by students, parents, teachers and the community as a whole.

Find Out More @ Kickstarter

Published on July 12, 2011 04:18

DSK Rape Case Takeaway No. 6: Alleged Victims Can Change the Script

DSK Rape Case Takeaway No. 6: Alleged Victims Can Change the Script by Akiba Solomon | Colorlines

Last week, a variety of media harped on the imminent demise of the rape case against former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn because of his accuser's so-called credibility problems. Despite the backlash (and in notable cases the backlash to the backlash) against her, the Guinean Sofitel housekeeper isn't going away quietly.

She proved that last Wednesday when she rightfully sued Rupert Murdoch's New York Post for libel. From a copy of the filing, which refers to stories and headlines like, "DSK MAID A HOOKER: 'Took care' of guests on the side":

"In, several news articles published in both the hard copy and online editions of the New York Post on July 2, 2011, July 3, 2011 and July 4, 2011, Defendants falsely, maliciously and with reckless disregard for the truth stated as a fact that the Plaintiff is a 'prostitute,' 'hooker,' 'working girl" and/or 'routinely traded sex for money with male guests' of the Sofitel hotel located in Manhattan. Defendants also falsely stated in the New York Post that the Plaintiff recently engaged in acts of prostitution with various men at a hotel located in Brooklyn following the sexual assault and while under the protection of the Manhattan District Attorney's Office and that she was turning tricks on the taxpayers' dime."

What makes the prostitution accusation so egregious is that it's based on the word of an unidentified source on or affiliated with Dominique Strauss-Kahn's investigative team.

Read more @ Colorlines

***

Akiba Solomon writes Colorlines' Gender Matters blog and is an NABJ-Award winning writer, freelance journalist, editor and essayist from West Philadelphia. A graduate of Howard University, the Brooklyn resident co-edited Naked: Black Women Bare All About Their Skin, Hair, Hips, Lips, and Other Parts (Perigee, 2005), an anthology of original essays and oral memoirs about Black women and body image.

Published on July 12, 2011 04:12

July 11, 2011

"Far Away," But So Close to Home

"Far Away," But So Close to Home: Why Marsha Ambrosius' Video May have Fallen on Deaf Ears by Jeffrey Q. McCune, Jr. | special to NewBlackMan

Earlier this year, there was a new viral video repeatedly being sent to my facebook and university in-boxes: Marsha Ambrosius' video, "Far Away." As a gender studies professor, and a mentor to young men and boys, friends and colleagues passed along the link to this video commending its efforts to bring awareness to bullying and hate crimes against LGBT folk, particularly black gay men. Up until the recent 2011 BET Awards, where the video was nominated for "Video of the Year," I was convinced that this video was a vague memory, shadowed by the other viral stories: from Eddie Long's coercive complexities to the black church's gay marriage question. Indeed, the video was somewhat muted by these explosions in media. However, seeing the numerous acts of violence against black gay men and black men more generally in this year alone, I wonder why this performance has not fueled greater buzz beyond "can you believe she had two black men kissing in this video" or "why are people so cruel and violent against gay people?" As such a performance surely underscores an issue often muted from media and black community conversation, why has no action or community outrage moved from the screen to the pews, classrooms, or the streets?

The "Far Away" video follows closely Ambrosius' male best friend and his male lover, as they walk through the (neighbor)hood and into a scene of danger (physical assault by other men in a park), and concludes with another scene of violence (the best friend's suicide by overdose in his own front room). The music plays against the action, as Ambrosius sings of her memories, her pain, and her loss of a friend at the hand of senseless and unwarranted violence. This powerful video recalls an often-undermined element of black feminism—the importance of black men's well being in relation to, not in exchange for, black women's health and well-being.

The video, drawn from Ambrosius' second-released single on her album Late Nights and Early Mornings, is most provocative as it takes a clear stance on gay bullying and hate crimes. However, it is also bold in its blatant display of man-on-man love, not lust, as the central relational image throughout the video. This artistic work, if anything, returns us to other moments where "music was message"-informed by the love, pain, and struggles of everyday experiences. Here, Ambrosius' video demonstrates the way in which hate and hostility toward gays not only produces violent acts, but can also lead to spirit-murder which ends with suicide. With such bravery, carefully crafted drama, and a clear-cut message, it is hard to believe that viewers do not "get it," after viewing this powerful exposition of such current and sad times which we live. As the men walk through the (neighbor)hood—the space which birthed their love--they become fast victims of violence in the name of hating sexual and/or gender differences.

So, how or why might this video and its message have fallen on deaf ears?

First, the video itself is in conversation with some preexisting kitchen talk. The primary one is that of the "down-low," or DL—conventionally understood as "masculine men who pass off as straight when they are actually gay." Due to the overwhelming media frenzy over the DL, I believe that many viewers may find it difficult to SEE these men as "gay." Especially, as the video begins with what visually suggests that the Ambrosius and her best friend are actually lovers. With this in mind, on one hand this video becomes about the punishment these men deserve for being unavailable to the sisters who are in search for "good black men." While on the other, it is about some affront to black hetero-masculinity, where visible "male-on-male" love endangers the cult of black manhood. These understandings ignore the reality of some black men who are Gay, Masculine, and living DL (discreet lives)— a combination which often responds to desires for privacy in a world which constantly surveillances them.

Second, the use of conventionally masculine men allows viewers to forget that those who DO NOT conform to gender standards are often at greater risks of violence. This is largely because men who break tradition of what is understood as properly masculine are highly scrutinized and are more available targets for criticism. Indeed, this is most significant as we reflect upon the bullying of our gay and straight youth who may, or may not, perform gender outside of certain norms. While it is important to foster acceptance and affirm sexual difference, there is as much a need for our communities to embrace gender differences as well.

Third, while this video has been passed along to me for its content on bullying, I also believe it says something even more bold about what is necessary to end these heinous acts. A somewhat random and odd moment appears in the video, where a mother and her son encounter the handholding couple and the mother pulls her son away from Ambrosius' best friend. [side note: her son's future could be his present]. Her treatment of the couple as "nasty, embarrassing, disgraceful," sends a clear message to her son that love is conditional. This attitude fuels hate and anchors violence and suicide. In fact, this moment along with other imaginable instances, instigates the notion that black gay men loving each others is not revolutionary and reverent, but to be ridiculed and denied. To eradicate violent acts in the lives of ALL our children and adults, we must disrupt our cycle of teaching hate—too often couched in lessons of manhood, (non)Christ-like approaches, and fear. This, for me, was a compelling moment where "Far Away," inadvertently gets at the systemic ways we infect our young men with violent potential.

Finally, while I wholeheartedly applaud Ambrosius' achievement here, there is something very contradictory and odd about one line in her closing message: "I lost a friend to suicide, and I'm asking all of you to support alternative lifestyles." This line complicates the work that Ambrosius does throughout the video. Indeed, she means to suggest that LGBT folks need community support and to feel apart of the community; yet, this coda appears to offer up LGBT lives as merely a thing put on and taken off. The word "lifestyle," implies some degree of freedom to select a community of folks, with whom one shares similar ideas and values. In this case, "a gay lifestyle" suggests selecting a community where you are more likely to beaten, or even killed. Indeed, if selecting a "lifestyle" was so easy— in order to avoid such tragedies and violence—I would contend that many would peel off their gayness and live in the privilege of never having to run for their lives because of who they love or how they perform their gender. Unfortunately, this framing of gayness as some "bad choice" or "bad lifestyle" is not the product of Ambrosius, but a larger understanding of gayness that allows us to not only dismiss human value and beauty, but also the violence that destroys these bodies. For this reason, her word-choice here—and its call upon old framings of gay lives—marks a poor closing for such a powerful visual statement.

Still, hats off to Marsha Ambrosius for disrupting the monotony of pop and daring to assert a political, provocative, and passionate voice. While I would love to say Ambrosius' nomination for the BET award for "Video of the Year" was a sign of consciousness, I am more apt to believe that it was a recognition of her artistic genius and skill, rather than a concern for her critical message against violence. Indeed, questions remain. How can this performance be restored and used to create a necessary dialogue in spaces often mute on issues of gender and/or sexual difference? When will we begin to allow the viral sound bytes to infect and affect us in ways that our anger and outrage are incurable and only treatable through collective action? These matters are too close to home for us not to act and save lives.

***

Jeffrey Q. McCune, Jr. is an Assistant Professor of American Studies and Women's Studies at the University of Maryland-College Park. He is author of the forthcoming manuscript, Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and Politics of Passing (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming 2012).

Published on July 11, 2011 20:11

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | Day #11: Miki Howard —"Baby Be Mine"

20 Years in 28 Days: A Marriage in Music Day #11: Miki Howard—"Baby Be Mine"by Mark Anthony Neal

If you were to ask me, I'd suggest that I have tried choreograph every aspect of my adult life, for better or worse. That was not the case in the fall of 1987, as I was scuffling along trying to figure out my next move, professionally and personally. The lifeline was random phone call in late November. As I've come to understand it, my future wife was at her job at the NYU bookstore when one of her colleagues, and older Black woman, implored her to call me, on the basis that "I owed her a dinner." When she called to touch base, I was surprised, maybe even shocked, but knew to take advantage of the opportunity.

We set up a date, a Friday night. Dinner at the Dallas BBQ in 8th Street, the movie was Nuts with Barbara Streisand and Richard Dreyfuss. She wore a white sweater, beige knit pants, and brown knee length boots. By all accounts the date itself was a success. The trip home has been some subject of debate over the past 23½ Years. I had prepared a cassette take specifically for the outing—the opening song on the cassette, which I still possess was Miki Howard's "Baby Be Mine," which still has a special place in my heart. Also remember Prince's "Forever in My Life" was also on that tape.

It was a rainy night and I was driving my first car, a light blue Chevy Nova—the one that was built on the Toyota Corolla—the same car that would drive us to our first post-marriage residence in Fredonia, New York in 1991. As such I didn't quite understand the air circulation thing yet; couldn't quite figure out how to un-fog my windshield as we drove up the Westside highway.

named mine "Louise"Amazingly we made it back to the Bronx in one piece. There was a quick peck on the lips, and as I recall it, she ran out of my car, at least that's how I described it to FP the next day. I wasn't sure that I would see her again. She of course has no memory of it going down that way, as it has become one of the seminal events in our relationship that we have conflicting opinions about what happened. Another was our first meeting with our oldest daughter, who was less than two weeks old when we first met her and I swear that at that age she already had the dexterity to pull my glasses off my eyes. The wife simply says that they fell off in my nervousness and perhaps it was that same nervousness that has gotten the better of my memories and about that first date in 1987. Thankfully it wasn't the last.

named mine "Louise"Amazingly we made it back to the Bronx in one piece. There was a quick peck on the lips, and as I recall it, she ran out of my car, at least that's how I described it to FP the next day. I wasn't sure that I would see her again. She of course has no memory of it going down that way, as it has become one of the seminal events in our relationship that we have conflicting opinions about what happened. Another was our first meeting with our oldest daughter, who was less than two weeks old when we first met her and I swear that at that age she already had the dexterity to pull my glasses off my eyes. The wife simply says that they fell off in my nervousness and perhaps it was that same nervousness that has gotten the better of my memories and about that first date in 1987. Thankfully it wasn't the last.

Published on July 11, 2011 19:23

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.