Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1069

August 1, 2011

Review Essay | Dirty South: OutKast, Lil' Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Invented Hip Hop

The New Mouth, New (Post Civil Rights) 'Dirty South' by R. N. Bradley | Popmatters

"It is officially a new day, I am officially the new mouth, and these are the emcees of a new South!"–Killer Mike, "Reakshon"

After receiving Ben Westhoff's new book Dirty South: OutKast, Lil' Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip Hop I immediately went into defense mode. As in rapper Pastor Troy "We Ready" defense mode. All too familiar with the dismissal of the South and southern hip-hop I waited, albeit a bit too readily, for Westhoff to say something, anything, that would set me off.

I put away my armor.

Westhoff weaves a humorously awkward yet honest narrative about some of the voices that frame what Americans know as the 'Dirty South'. Whether commenting on the slight discomforts of partying with "Uncle" Luke Campbell – "as married, STD-free man, neither option bears much appeal, but all I can do is laugh noncommittally" – or interviewing an apparently edgy Soulja Boy – "Robbing Soulja Boy hadn't been on my list of the day's priorities" – Westhoff presents his audience with a smorgasboard of experiences that are often overlooked in conversations about hip-hop culture.

Very apparent in Westhoff's understanding of southern rap music is the hustle, an entrepreneurial pursuit to get paid. Varying degrees of the hustle trope intersect throughout Westhoff's musings which speak to the murky intersections of contemporary hip-hop with mainstream American culture. From the personal hustle to set up and execute interviews with initially unwilling rappers to the corporate hustle of interviewees like Mr. Collipark (AKA DJ Smurf), industrialism seeps throughout the book. In some passages, however, the hustle metaphor plays into standing (dis)beliefs about the inability for southern rap to assimilate into a hyper-capitalist culture. The nod towards southerners' hustling of their mixtapes as "grassroots", for example, re-enforces the separatist notions that Westhoff sets out to disavow.

I most appreciate Westhoff's attempts to combine both nationally known southern rappers with more regionally appealing acts like Houston's Trae the Truth. Westhoff flexes his investigative journalism skills, here, he's done his homework. As I continued to read, however, I searched for something deeper than the work of a journalist and his collected stories, I sought a more critical approach to how hip-hop shapes and challenges our understanding of the South after the Civil Rights Movement. The attempt to situate one's self in a newly integrated social network, the search for a discourse in which to speak to these changes, and, finally, "integrate" into a broader American community are some of the peculiar challenges post-Civil Rights era southerners continue to face. Borrowing from rapper Andre 3000, "the South [still] got something to say!"

Read the Full Essay @ Popmatters

Published on August 01, 2011 19:50

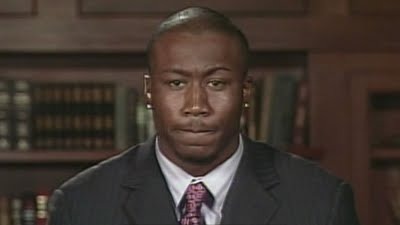

Brandon Marshall and the Challenge to Mental Health Treatment Inequality

Vulnerable: Brandon Marshall and the Challenge to Mental Health Treatment Inequality by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

On Sunday, amid all the hoopla about the start of NFL training camp, player movement, and the start of the NFL season, Brandon Marshall quietly told the world a secret, announcing that he was living with a Borderline Personality Disorder.

Right now today, I am vulnerable, I making myself vulnerable, and I want it to be clear that this is the opposite of damage control. The only reason I am standing here today is to use my story to help others who may suffer from what I suffer from, from what I had to deal with. I can't explain to you and paint a vivid enough picture for you guys where I been in my life, probably since the end of my rookie year.

Noting that neither the cars nor the fame, neither the success on the field nor the joys experienced off the field resulted in happiness, Marshall highlighted the despair that he has experienced during his life:

I haven't enjoyed not one part of it and it's hard for me to understand why . . . . One of the things I added to my prayer was for God to show me my purpose here. When I got out of the hospital, I called my videographer and I said, Rob, grab your camera and just come to my house and just start shooting. I said I'm very depressed right now, I probably won't talk, I probably won't even leave my theater room, but you just shoot and don't stop shooting. I said, I don't know where we're going with this, I don't know what's going to come out of this, but something good is going to happen.

Marshall is not the first high-profile African American athlete to publicly document the struggles with mental illness. Several years ago, Ricky Williams spoke about his illness (Social Anxiety Disorder) "to up the awareness and erase the stigma." Likewise, Ron Artest, who has publicly acknowledged his own disease, has gone beyond chronicling his own story, testifying before congress while raising money (through auctioning off his championship ring) for mental health awareness among youth.

The reaction to Marshall's revelation, like that of Ron Artest and Ricky Williams, illustrates the ways in that definitions of black manhood curtail public discourse and treatment of black mental illness. Responding to Ron Artest courageous announcement about his own mental health struggles, Mychal Denzel Smith offered an important context:

Black men don't go to therapy, they go to the barbershop." I can't count the number of times I've heard this throughout my life, nor relate how embarrassed I am to have actually believed this at one point. The resistance black men exhibit toward mental health awareness is astounding. The belief, in my estimation, is that admitting to and/or seeking help for a mental illness makes one less of a man. We have come to define masculinity/manhood as "strong," meaning silent, emotionless, stoic and uncaring. To our detriment, black men have accepted, embraced, and perpetuated this idea and left a community of emotionally stunted black men so repressed that the mere mention of a psychiatrist is met with a chorus of hearty laughter. It doesn't prevent us from suffering at the hands of mental illness, it's just that black men prefer to self-medicate with marijuana and Jesus (not necessarily concurrently).

Marc Lamont Hill also focuses on context, providing an important historic reminder as to why African Americans (beyond culture, machismo, or cultural practices) often resist and otherwise dismiss mental health challenges:

Since slavery, the American scientific establishment has functioned as an ideological apparatus of White supremacy by advancing and normalizing claims of Black moral, physical, and intellectual inferiority. As a result, the last four centuries have witnessed the production of deeply racist beliefs and practices that justify the abuse, exploitation, and institutionalization of "flawed" and "diseased" Black bodies. . . . By using mental illness to justify the denial of full humanity, freedom, and citizenship to Blacks, as well as ascribe mental pathology to those who operate against the interests of the White supremacist capitalist State, the American medical establishment has engendered a healthy and persistent distrust among Black communities.

The absence of treatment, thus, contributes to criminalization; yet, criminalization, leads to a lack of attention to mental health issues. Marshall, who has had his share of off-the-field troubles, has been vilified by the media and the public at large, demonstrating how stereotypes and white racial frames imagined him (and other African American fighting mental illness) not as someone who was sick but as a sick individual. His experiences reflect a systemic failure to address mental health within the African American community; it reflects the power of white racial framing and the tendency to criminalize and pathologize rather than treat the symptoms of mental illness. While reflecting the ways in which mental illness poses a threat to hegemonic definitions of manhood, the failure to sufficiently address mental health issues within the African American community illustrates the ways in which criminalization of the black body reconstitutes treatable symptoms as justification for incarceration. To understand criminalization is to understand the failure to treatment mental illness within the African American community

Here are some facts to consider

African Americans constitute over 25 percent of those in need of mental health careSince 1980, suicide rates among African Americans has increased 200 percentRates of depression among black women are 50 percent higher than those of white women 25% of African Americans live without health insurance 35% male prisoners have Borderline Personality Disorder 25% of incarcerated women have been diagnosed with BPD10% of people who suffer from BPD commit suicide Blacks are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than with other mood disorders, even when the symptoms point to a mood disorder (whites more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorder when symptoms mirror schizophrenia)Blacks are less likely to be given anti-depressant medicationsBlacks are least likely group to receive therapy Only 1:3 African Americans who need mental health treatment or care receive itAfrican Americans constitute only 2 percent of the nation's psychologists and psychiatrists

According Dr. Regina Benjamin, mental illness continues to plague the African American community in disproportionate rates: "Mental health problems are particularly widespread in the African-American community," noted the U.S. Surgeon General. "In 2004, nearly 12 percent of African Americans ages 18-25 reported serious psychological distress in the past year. Overall, only one-third of Americans with a mental illness or a mental health problem receive care and the percentage of African Americans receiving services (nearly 7 percent) is half that of non-Hispanic whites."

Recognizing this problem and the many issues at work, it is important to highlight the courageous activism undertaken by Marshall, Williams, and Artest, all of whom have not only pushed back against the stigmas and fears associated with mental illness, especially as it relates to manhood, but whose public pronouncements have challenged hegemonic stereotypes and narratives that tend to criminalize the black body. Their resistance elucidates the consequences of American racism in contributing to mental health problems all while contributing to a systematic erasure of these problems from public discourse and policy. Marshall, like Williams and Artest, made clear that he is neither a criminal nor a bad person (a common narrative from the press and fans) but someone who is sick, someone who has gotten treatment, and someone who has long needed support rather than demonization. He, like so many African Americans erased from public consciousness, just needed help. Racism so often prevents this from happening. So next some media pundit denounces today's (black) athletes for reticence and political cowardice, remember Marshall, Williams and Artest, all of whom took a stand against inequality in the treatment of mental health problems.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on August 01, 2011 12:40

Tricia Rose on America's Growing Inequality

Watch the full episode. See more Need To Know.

Tricia Rose is Chair and Professor of Africana Studies at Brown University. Professor Rose is most well-known for her ground-breaking book on the emergence of hip hop culture, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. She is also the co-editor of the youth music and youth culture collection: Microphone Fiends, and in 2003 published a rare history of black women's sexual life stories, called Longing To Tell: Black Women Talk About Sexuality and Intimacy. Rose's most recent book is The Hip-Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop-And Why It Matters.

Published on August 01, 2011 12:18

July 31, 2011

Hip Hop and Health?

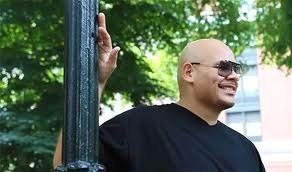

Fat Joe Minus 88 Pounds

Fat Joe Minus 88 Pounds

Rap Gets a Physical

Soundcheck with John Schaefer

WNYC | Wednesday, July 27, 2011

With famous names like "Notorious B.I.G." and "The Fat Boys," it's easy to believe that hip hop hasn't always been all that healthy. Yet hip hop does have a rather robust history of artists, from Dead Prez to MF Doom, using their raps to promote healthier lifestyles. To explore hip hop's complicated medical history, we'll be joined by Mark Anthony Neal, Professor of Black Popular Culture at Duke University, and Byron Hurt, the filmmaker behind the upcoming documentary Soulfood Junkies . Plus, we get a housecall from the "Hip Hop Doc"- Dr. Olajide Williams, President and Founder of Hip Hop Public Health and Public Enemy frontman Chuck D.

Published on July 31, 2011 19:18

July 25, 2011

Men in Love--A Film Short by Keith Davis

Men in Love Written/Directed by Keith Davis

"Following a bitter break-up, Leo's best friend takes him out to meet a new woman and 'get over' his ex.

But after a steamy and unexpected encounter with a stranger he's forced to face what most men fear: they don't realize they're in love with the right woman until it's too late."

Featuring: Benton Greene, Duane Cooper, Bianca Jones, Adepero Oduye

Running Time: 11 minutes 45 seconds

Published on July 25, 2011 19:06

The Bennus--Jamyla, Pierre & Kids--in O Magazine

Meet the Bennus: Jamyla and her husband, Pierre, co-founders of a Baltimore-based organic haircare and skincare line, and their sons, Osei and Sadat.

No Member of This Family Is Perfect, but Together They're Awesome As told to Penny Wren | O, The Oprah Magazine

Jamyla: We met 13 years ago on a street corner in New York. The next day we saw each other again in Brooklyn Heights. I was on roller blades...

Pierre: ...and I was sitting on a bench, writing in my journal. As she passed by, we gave each other the "Wait, aren't you—?" look. She sat down, and we talked for hours.

Jamyla: Six months later we moved in together.

Pierre: And within another five months we were married.

Jamyla: I was 23, Pierre was 25. If I met a young couple like us today, I'd say, "Aww, look at them, so in love." But I'd also think, "What are you kids doing?!"

Pierre: We were young. But we waited ten years before we had kids. We gave ourselves time to be selfish.

Read More

***

Jamyla & Pierre Bennu on Left of Black

Published on July 25, 2011 18:05

Criticism 52: 3 & 4 | 'The Wire' Issue

Preface

Robert LeVertis Bell

Preface

Robert LeVertis BellPaul M. Farber

pp. 355-357 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (59k) | [image error] Summary

Realism and Utopia in The Wire Fredric Jameson pp. 359-372 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (528k) | [image error] Summary

"The Game Is the Game": Tautology and Allegory in The Wire Paul Allen Anderson pp. 373-398 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (546k) | [image error] Summary

"A Man without a Country": The Boundaries of Legibility, Social Capital, and Cosmopolitan Masculinity Mark Anthony Neal pp. 399-411 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (481k) | [image error] Summary

The Last Rites of D'Angelo Barksdale: The Life and Afterlife of Photography in The Wire Paul M. Farber pp. 413-439 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (1443k) | [image error] Summary

Constrained Frequencies: The Wire and the Limits of Listening Adrienne Brown pp. 441-459 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (513k) | [image error] Summary

The Depth of the Hole: Intertextuality and Tom Waits's "Way Down in the Hole" James Braxton Peterson pp. 461-485 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (614k) | [image error] Summary

Greek Gods in Baltimore: Greek Tragedy and The Wire Chris Love pp. 487-507 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (543k) | [image error] Summary

Walking in Someone Else's City: The Wire and the Limits of Empathy Hua Hsu pp. 509-528 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (512k) | [image error] Summary

"Precarious Lunch": Conviviality and Postlapsarian Nostalgia in The Wire's Fourth Season Robert LeVertis Bell pp. 529-546 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (542k) | [image error] Summary

Capitalist Realism and Serial Form: The Fifth Season of The Wire Leigh Claire La Berge pp. 547-567 [image error] HTML Version | [image error] PDF Version (523k) | [image error] Summary

Index to Volume 52 of Criticism(2010) pp. 569-571 [image error] PDF Version (440k) | [image error] Summary

Published on July 25, 2011 06:18

July 24, 2011

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | #13 The Moments—"Look at Me I'm In Love"

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music #13 The Moments—"Look at Me I'm In Love"by Mark Anthony Neal

Driving south on the West Side highway, below the GW Bridge, presents one of the most beautiful glimpses of New York City and New Jersey, separated by the Hudson. One of the joys that I took from those early days of my relationship with my future life partner, was picking her up from the Butler Houses and driving downtown via the West Side Highway. It was one early Saturday morning in February of 1988, when we planned a day in the village. I was in the practice of making cassette tapes for each one of our planned outings, but this time the woman switched things up on me, and presented me with her own tape of music.

Already pretty arrogant about my musical taste—and what I thought was the mind of an untapped audiophile, I wasn't suspecting to hear anything on her tape that would surprise me—and she didn't. But one of the gems on the tape was The Moments' "Look At Me I'm in Love." The song had long been one of my favorites—was popular on NYC radio in the mid-1970s when I had my first crush. The group even recorded a French language version of the song, that was more than helpful when I struggled through two—God-awful—years of French at Brooklyn Tech. To have it included on her tape was a sweet surprise—one that led me to take my eyes off the road a little too long, just enough to nudge the car in front of me on a slow moving West Side Highway.

Already pretty arrogant about my musical taste—and what I thought was the mind of an untapped audiophile, I wasn't suspecting to hear anything on her tape that would surprise me—and she didn't. But one of the gems on the tape was The Moments' "Look At Me I'm in Love." The song had long been one of my favorites—was popular on NYC radio in the mid-1970s when I had my first crush. The group even recorded a French language version of the song, that was more than helpful when I struggled through two—God-awful—years of French at Brooklyn Tech. To have it included on her tape was a sweet surprise—one that led me to take my eyes off the road a little too long, just enough to nudge the car in front of me on a slow moving West Side Highway. It was just a fleeting moment in a new relationship, that was getting serious, but a moment we have gone back to, many times. I don't know what it continues to mean for her, but for me it was just a small glimpse into her sweetness and her early understandings of the small gestures that move me. She has long ceded those kind of small musical moments to my "life of the mind," where music just becomes the opportunity for me to expound upon more data.

***

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | #12: Luther Vandross —"Wait for Love"

Published on July 24, 2011 18:34

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music | #12: Luther Vandross —"Wait for Love""

20 Years in 27 Days: A Marriage in Music #12: Luther Vandross—"Wait For Love"by Mark Anthony Neal

In my mind, Luther Vandross The Night I Fell In Love (1985) found him at the peak of his powers; nowhere is that more evident than on the stirring ballad "Wait For Love," notable for his unwillingness to end the song. The extended two-minute-plus riff that he does at the song's closing should be required listening for every wannabe R&B singer, as an example of how you hold on to an audience, by giving the impression that they've yet to get your best.

Too many of the younguns shoot their load in the first verse and there's little reason to stay around especially if they're singing badly crafted material. Part of Vandross' genius was in his patience—and he made us all better listeners because of it.

Patience. I think about that often with regards to the relationship I have shared for nearly 24-years with Gloria Taylor-Neal.

We had survived out first date, foggy windshield and all, and were going through the paces of a new relationship in December of 1987, getting to know each other, though we had been friends for about 5 years. The timing of it all meant that Christmas would take on a greater significance than either of us were prepared for, though there would be no family meet-in-greet over the holidays, simply too soon for those kind of perfunctories. Nevertheless we planned our first Christmas eve together; We'd meet at the Herald Square Macy's, in "The Cellar" next to the David's Cookies (can still smell that spot years later) and then head downtown to the Village to dinner at an upscale Falafel spot that she frequented. Sounds perfect, right?

Knowing how crazy parking would be by Herald Square, my idea was to park at a meter on 10th Avenue between 33 and 32nd streets, where I was working for a data imaging company called Downing Data (the dark years). Popped in my quarters, knowing this would have to be a short turn-around if I was to make to Macy's and back—with the woman—without getting a ticket (it surely wasn't the first and wouldn't be the last—got a few tow receipts to prove it, but that's for another day). In my haste—I locked my keys in the car (it was the first time, and surely wouldn't be the last. One day my oldest daughter will tell the story of her father locking his keys in a running car). This is 1987, ain't no Blackberries or iPhones.

So I'm standing on the corner of 10th and 33rd trying to decide to I get the locksmith to unlock the car or go get the woman; I chose to get the woman, who was just prepared to leave, accepting that she'd been stood up, when me and my tweed jacket, and Khakis with no socks, came running though "The Cellar" at Macy's (was still in my 5K & 10K days). An hour later, I'm spending my last bit of cash, getting my car keys back—with the woman beside me—as we head downtown to dinner. Alls well that ends well, right?

So dinner is progressing, we exchange gifts; sigh, I'm way too casual about this. She gives me a Macy's gift—a sweater if I recall, I give her a box of chocolates—the same box of designer chocolates that I had given out as gifts to lady friends throughout my college years, the same box of chocolates that I got for free from the stationary warehouse that employed me throughout college (Pen & Things, formerly on the corner of Astor and Broadway). Thank-God she loves chocolate.

So dinner is progressing, we exchange gifts; sigh, I'm way too casual about this. She gives me a Macy's gift—a sweater if I recall, I give her a box of chocolates—the same box of designer chocolates that I had given out as gifts to lady friends throughout my college years, the same box of chocolates that I got for free from the stationary warehouse that employed me throughout college (Pen & Things, formerly on the corner of Astor and Broadway). Thank-God she loves chocolate. Then come the realization that I have no cash and the restaurant doesn't take credit. Sigh, shit, sigh is what I recall trying to figure things out in the bathroom. In what my wife will suggest is a recurring theme in our relationship, I asked her to bail me out and then asked her forgiveness (remember those tow tickets, and then there's the story of the brakes).

That day, I learned that this was a woman that was willing to "Wait for Love;" something that would serve both of us in the future as I tried to figure out what I was gonna do when I grew up.

Published on July 24, 2011 14:35

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.