Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1068

August 4, 2011

Does It Have to Be The Shoes?: Macklemore and Ryan Lewis' "Wings"

Does It Have to Be The Shoes?: Macklemore and Ryan Lewis' "Wings" by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

"It's gotta be the shoes"—Mars Blackmon

These six words in many ways defined the late 1980s and 1990s, encapsulating the rise of hip-hop, NIKE, Michael Jordan, and the racial-class narratives embedded in each of them. For a teenager growing up in the 1980s, in many ways this phrase defines my generation. Rather than generation X, we are the "It's gotta be the shoes generation."

The problems inherent in such an ethos crystallized for me after watching the new video from Seattle's very own Macklemore and Ryan Lewis.

"Wings," directed by Zia Mohajerjasbi, initially plays on the childhood memories associated with Air Jordans, ideas that likely resonate with many of this generation today.

I was seven years old, when I got my first pair

And I stepped outside

And I was like, Momma, this air bubble right here, it's gonna make me fly

I hit that court, and when I jumped, I jumped, I swear I got so high

The joy of success on the court, of ballin' like the big boys, was not a pure accomplishment, but one that was wrapped up in commercial ideas and commodification from the jump. The purity of being able to touch the net was never, in his mind, indicative of his own skills but that of the shoes. It had to be the shoes.

Yet, the tune (in the song and for the young boy in the video) quickly changes, away from childhood dreams and nostalgia for the sweet smell of brand-new kicks, to the painful realities about shoes.

And then my friend Carlos' brother got murdered for his fours, whoa

See he just wanted a jump shot, but they wanted to start a cult though

Didn't wanna get caught, from Genesee Park to Othello

Carlos' brother, like other kids, in the 1980s, learned all too painfully about the value placed on a pair of shoes. Worth more than a life; worth more than a future; the quick transition from "wanting to be like Mike," to fly, to stark reminder about those killed over Mike's shoes is a powerful message. Here, Macklemore not only illustrates the value placed upon shoes but challenges listeners to think beyond the nostalgia for balling in new Jordans to remember those who died for those new air Jordans.

Yet, the song is not purely about the cultural meaning and history behind shoes, but a powerful commentary on commodification. It is a story of the valued put on shoes culturally, economically, socially, athletically, and stylistically, even though shoes are shoes.

We want what we can't have, commodity makes us want it

So expensive, damn, I just got to flaunt it

Got to show 'em, so exclusive, this that new shit

A hundred dollars for a pair of shoes I would never hoop in

Look at me, look at me, I'm a cool kid

I'm an individual, yea, but I'm part of a movement

My movement told me be a consumer and I consumed it

They told me to just do it, I listened to what that swoosh said

Look at what that swoosh did

See it consumed my thoughts

Highlighting the ways in which products define our sense of identity, demark coolness, and otherwise tell the world something about us, "Wings" laments the power ascribed onto shoes. It questions that stock we put into consumption and products, a process that merely enhances the stock value of companies like NIKE.

In this regard, the song and the video simultaneously show a process, the difficulty in challenging the marketing and message to say, "they are just a pair of shoes." The allure of the American Dream, of coolness, and the product are seductive. In fact, this is part of the marketing strategies of companies like NIKE, which invest in the production of image and advertizing, all while minimizing costs of labor. In selling a dream, in selling hipness, athleticism, coolness, and an overall image, the shoes themselves and the conditions of production are erased and rendered meaningless.

Sue Collins, in "'E' Ticket to NIKE Town, describes this tactic as "commodity fetishism." It is "the kind of "magic" that occurs when we displace value as a product of human labor by projecting it onto objects as if the value were inherent. Marx described a commodity as a mysterious thing because 'in it the social character of men's labor appears to them as an objective character stamped upon the product of that labor; because the relation of the producers to the sum total of their own labor is presented to them as a social relation, existing not between themselves but between the products of their labor.'" She continues as follows:

Fetishism in postmodern consumer culture entails emptying commodities of meaning or 'hiding the real social relations objectified in them through human labor' to make it 'possible for the imaginary/symbolic social relations to be injected into the construction of meaning at a secondary level.' Production, then, empties, and advertising fills, and in this way use value is subsumed by exchange value. The Nike swoosh and the Jordan brand as cultural commodities not only constitute a symbolic code, they also take on a system of significations, coded abstractions realized by "ideological labor," to borrow from Baudrillard. In the fetish theory of consumption, the so-called magical substance of consumer products is really part of a generalized code of signs, what Baudrillard refers to as "a totally arbitrary code of difference, and that it is on this basis, and not at all on account of their use values or their innate 'virtues,' that objects exercise their fascination."13 In advanced capitalism, objects lose any real connection with their practical utility and "instead come to be the material correlate (the signifier) of an increasing number of constantly changing, abstract qualities."

Whether in the pain and suffering of those who labor in NIKE factories, or those who died over the shoes, we can see the damages resulting from commodity fetishism. "Wings" highlights the production of consumers obsessed with shoes not as a functional tool but as a commodity that encapsulates a myriad of narratives and signifiers.

What I wore, this is the source of my youth

This dream that they sold to you

For a hundred dollars and some change

Consumption is in the veins

And now I see it's just another pair of shoes

This song spoke to me in so many ways: its message resonates with my own childhood experiences and my constant pledge of allegiance to the shoes (and the matching hats); it connects to the persistent inner battle between my critical self that understands commodity fetishism and the realities of worker conditions and the consumer in me that wants; and mostly it speaks to me as a father who increasingly struggles in helping my daughter see those shoes, sweatshirt, jeans, etc as neither sources of joy nor signifiers of cool but simply clothes. I am hoping that her generation will heed the message of "Wings" and not follow in the footsteps of the "it's gotta be the shoes" generation.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on August 04, 2011 07:55

Gospel Legend DeLois Barrett Campbell Goes Home

Gospel Great DeLois Barrett Campbell Dies by Stella Foster | Chicago Sun-Times

DeLois Barrett Campbell--one of three sisters who made up Chicago's legendary gospel trio the Barrett Sisters--died Tuesday.

She was in her 80s.

The Barrett Sisters began singing and harmonizing gospel music during the 1940s in a religious family of 10 children on the South Side of Chicago.

Their father, Lonnie, was a singer and deacon at the Morning Star Baptist Church here, where young Billie and DeLois Barrett Campbell first sang with a cousin, Jonnie Mae Hudson.

When Hudson died in 1952, sister Rodessa Porter joined the trio, creating the Barrett Sisters

During the formative years of the early 1950s, the Barrett Sisters were inspired and influenced by the rich harmony, detailed phrasing and expressive presence of the Roberta Martin Singers.

Campbell, who suffered from acute arthritis in both knees, was confined to a wheelchair in her later years.

Before spending her 71st birthday at Trinity United Church of Christ in 1997, she told the Sun-Times, "I'm doing pretty good, although I'm completely confined to a wheelchair. We just returned from doing 10 concerts in Switzerland. You just keep going. For 60 years, I've been singing nothing but gospel."

Published on August 04, 2011 05:56

August 3, 2011

A Love Letter to The Bronx

The Grand Concourse

The Grand Concourse

A Love Letter to The Bronx by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Dear Bronx,

In the forty five years I've spent with you, you've taught me that creativity, beauty and compassion thrive most in the midst of hardship.

I first met you in the mid-60's when my girlfriend and I visited her sisters living hear the Grand Concourse and Claremont Park. She was black and I was white, and we had a hard time walking hand in hand in most of the city.

But not in the Bronx, We always felt safe here because the Bronx was a place where people of different races and cultures lived together and where people of different colors were part of the same families. Though we didn't stay together forever, I will never forget your hospitality during that challenging time in my life.

I then watched you burn from the Third Avenue El and the Number 4 train when I first stared working at Fordham in the early and middle 1970s. It felt awful, at the time, that I could do nothing to stop this tragedy, but I took heart from the community organizations that mobilized, first to stop the fires from heading North, and then that began to rebuild every neighborhood that had been left abandoned and burned.

Now virtually every vacant lot in the South Bronx is filled with new town houses, apartments and shopping centers. Thank you, Bronx for showing me and the world, that your spirit was unconquerable, and that all the people that wrote you off as hopelessly beaten and decayed were wrong.

And thank you Bronx, for giving the world hip-hop. In the middle of the 70's, when large portions of the Bronx were burning and music programs in the schools were being eliminated by budget cuts, young people in the Bronx, some African American, some Latino, some West Indian, were creating a new form of densely percussive music, using two turntables and a mixer, that made whole neighborhoods dance, and then incorporated poetry and rhyme to dazzle the imagination. What started in the Bronx soon spread into every neighborhood in the country, and eventually the world, where young people were marginalized, forgotten, and looked on with contempt. Hip Hop, your original product, became as popular as Rock and Roll was in its time.

Now,"The Message" that you spawned during those difficult years is given life daily, in the suburbs of Paris , in the favelas of Rio, in the immigrant quarters of Berlin In all of those places, where life is hard, young people use hip hop to say, in the words of Grand Master Flash; "Don't push me, cause I'm close to the edge, I'm trying not to lose my head. It makes me wonder how I keep from going under."

Thank you Bronx, not only for surviving, but for triumphing in the face of adversity, and setting an example of endurance and creativity for the entire world.

Sincerely,

Mark Naison Professor of African American Studies and History Fordham University

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depression and White Boy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on August 03, 2011 18:16

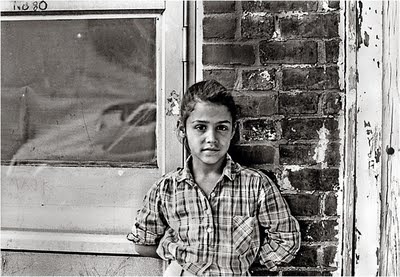

Papers of Puerto Rican Photographer & Activist Frank Espada to Be Housed at Duke University

Libraries Receive Photographs and Papers of Noted Photographer and Activist

Frank Espada Papers Come to Duke Universit.y

Durham, N.C. — Frank Espada began photographing Puerto Rican immigrants in the U.S. in the late 1950s. From 1979 to 1981, with support from a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, he focused his creative energies on documenting 34 particular Puerto Rican communities and their struggle to survive and thrive in America. Photographs from this project have been exhibited across the country and eventually led to the publication of The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Themes in the Survival of a People in 2006.

The photographs and papers that preserve the stories of the communities he visited are now available for research and study in Duke University's Special Collections Library. This collection of over 16,000 items joins the Library's Archive of Documentary Arts' growing collections of Latin American and Caribbean materials, including the work of photographers James Karales and Mel Rosenthal, both of whom documented Puerto Rican communities in New York City during the 1960s and 1980s.

Duke's Visual Materials Archivist Karen Glynn has been particularly impressed by the empathy she sees in Espada's work and points out the rapport visible in the images between the photographer and his subjects. Alex Harris, a founder of Duke's Center for Documentary Studies and of DoubleTake Magazine, is delighted that the Espada collection has come to Duke: "The Duke Library acquisition of Frank Espada's photographs and papers is a cause for celebration, an enormously important and intimate body of work about the Puerto Rican Diaspora, the civil rights movement, the HIV epidemic, and other subjects, photographs and words that encompass particular lives and yet manage to evoke our common humanity."

Espada was born in Puerto Rico in 1930 and emigrated with his family to the United States when he was nine years old, settling in New York City. He studied on the G.I. bill at the New York Institute of Photography, where he was a student of renowned photojournalist Eugene Smith. A life-long community organizer and activist, Espada has been actively involved in the National Welfare Rights Organization, the National Latino Media Coalition, the National Hispanic Manpower Association, and the National Association of Puerto Rican Drug Abuse Programs. In the 1960s, he became involved in the Civil Rights movement and worked for the City-Wide Puerto Rican Development Program.

Espada's rich and vital life is reflected in his archive, which includes 47 boxes of photographic prints, contact sheets, and negatives; oral histories; book manuscripts; correspondence; activist materials; teaching materials; and project materials. Fredo Rivera, a doctoral candidate in Art History examined the collection upon its arrival and is excited about the breadth of the collection. "Frank Espada does an incredible job at portraying the Boricua diaspora, and this collection evocatively portrays spaces of struggle and migration," said Rivera. "This collection goes beyond the portrayal of Puerto Rican migration, capturing the decline of the U.S. city as well as providing oral histories relative to the photographs. Despite the harsh social conditions portrayed, I was most impressed by the beauty of the photographs—they go beyond the documentary lens, providing a unique artistic portrayal that resonates with the viewer today."

Holly Ackerman, Librarian for Latin America and Iberia, anticipates that the Espada Archive will attract a wide range of scholars: "In the process of photographing specific communities of Puerto Ricans, Frank Espada has shown us the common ground of all the poor and marginalized people in the U.S. from the sixties to the eighties. Themes of protest, personal struggle and grassroots community solidarity are captured in a versatile collection that will serve researchers both from professional fields such as Social Work and Community Medicine and disciplines in the Social Sciences."

The Frank Espada papers are processed and available for use in the Special Collections Library. The finding aid for the collection can be viewed online. For more about Espada, visit his website. An exhibit drawn from the Frank Espada papers will be on view in Perkins Library in June 2012.

***

Contact / For more information Karen Glynnkaren.glynn@duke.edu919-660-5968

Published on August 03, 2011 17:16

SeeingBlack Radio: Race And The Debt Debate

Race And The Debt DebateSeeingBlack.com

SB ON THE RADIO--On the July 27 episode of What's At Stake (WPFW) Melissa Harris-Perry and Bill Fletcher Jr. join us to discuss the impact of race on the debt ceiling/budget debate.

Listen HERE

Published on August 03, 2011 12:54

8 Reasons Young Americans Don't Fight Back: How the US Crushed Youth Resistance

The Greensboro Four, 1960The ruling elite has created social institutions that have subdued young Americans and broken their spirit of resistance.

The Greensboro Four, 1960The ruling elite has created social institutions that have subdued young Americans and broken their spirit of resistance. 8 Reasons Young Americans Don't Fight Back: How the US Crushed Youth Resistance by Bruce E. Levine | Alternet

Traditionally, young people have energized democratic movements. So it is a major coup for the ruling elite to have created societal institutions that have subdued young Americans and broken their spirit of resistance to domination.

Young Americans—even more so than older Americans—appear to have acquiesced to the idea that the corporatocracy can completely screw them and that they are helpless to do anything about it. A 2010 Gallup poll asked Americans "Do you think the Social Security system will be able to pay you a benefit when you retire?" Among 18- to 34-years-olds, 76 percent of them said no. Yet despite their lack of confidence in the availability of Social Security for them, few have demanded it be shored up by more fairly payroll-taxing the wealthy; most appear resigned to having more money deducted from their paychecks for Social Security, even though they don't believe it will be around to benefit them.

How exactly has American society subdued young Americans?

1. Student-Loan Debt. Large debt—and the fear it creates—is a pacifying force. There was no tuition at the City University of New York when I attended one of its colleges in the 1970s, a time when tuition at many U.S. public universities was so affordable that it was easy to get a B.A. and even a graduate degree without accruing any student-loan debt. While those days are gone in the United States, public universities continue to be free in the Arab world and are either free or with very low fees in many countries throughout the world. The millions of young Iranians who risked getting shot to protest their disputed 2009 presidential election, the millions of young Egyptians who risked their lives earlier this year to eliminate Mubarak, and the millions of young Americans who demonstrated against the Vietnam War all had in common the absence of pacifying huge student-loan debt.

Today in the United States, two-thirds of graduating seniors at four-year colleges have student-loan debt, including over 62 percent of public university graduates. While average undergraduate debt is close to $25,000, I increasingly talk to college graduates with closer to $100,000 in student-loan debt. During the time in one's life when it should be easiest to resist authority because one does not yet have family responsibilities, many young people worry about the cost of bucking authority, losing their job, and being unable to pay an ever-increasing debt. In a vicious cycle, student debt has a subduing effect on activism, and political passivity makes it more likely that students will accept such debt as a natural part of life.

2. Psychopathologizing and Medicating Noncompliance. In 1955, Erich Fromm, the then widely respected anti-authoritarian leftist psychoanalyst, wrote, "Today the function of psychiatry, psychology and psychoanalysis threatens to become the tool in the manipulation of man." Fromm died in 1980, the same year that an increasingly authoritarian America elected Ronald Reagan president, and an increasingly authoritarian American Psychiatric Association added to their diagnostic bible (then the DSM-III) disruptive mental disorders for children and teenagers such as the increasingly popular "oppositional defiant disorder" (ODD). The official symptoms of ODD include "often actively defies or refuses to comply with adult requests or rules," "often argues with adults," and "often deliberately does things to annoy other people."

Many of America's greatest activists including Saul Alinsky (1909–1972), the legendary organizer and author of Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals, would today certainly be diagnosed with ODD and other disruptive disorders. Recalling his childhood, Alinsky said, "I never thought of walking on the grass until I saw a sign saying 'Keep off the grass.' Then I would stomp all over it." Heavily tranquilizing antipsychotic drugs (e.g. Zyprexa and Risperdal) are now the highest grossing class of medication in the United States ($16 billion in 2010); a major reason for this, according to theJournal of the American Medical Association in 2010, is that many children receiving antipsychotic drugs have nonpsychotic diagnoses such as ODD or some other disruptive disorder (this especially true of Medicaid-covered pediatric patients).

3. Schools That Educate for Compliance and Not for Democracy. Upon accepting the New York City Teacher of the Year Award on January 31, 1990, John Taylor Gatto upset many in attendance by stating: "The truth is that schools don't really teach anything except how to obey orders. This is a great mystery to me because thousands of humane, caring people work in schools as teachers and aides and administrators, but the abstract logic of the institution overwhelms their individual contributions." A generation ago, the problem of compulsory schooling as a vehicle for an authoritarian society was widely discussed, but as this problem has gotten worse, it is seldom discussed.

The nature of most classrooms, regardless of the subject matter, socializes students to be passive and directed by others, to follow orders, to take seriously the rewards and punishments of authorities, to pretend to care about things they don't care about, and that they are impotent to affect their situation. A teacher can lecture about democracy, but schools are essentially undemocratic places, and so democracy is not what is instilled in students. Jonathan Kozol in The Night Is Dark and I Am Far from Home focused on how school breaks us from courageous actions. Kozol explains how our schools teach us a kind of "inert concern" in which "caring"—in and of itself and without risking the consequences of actual action—is considered "ethical." School teaches us that we are "moral and mature" if we politely assert our concerns, but the essence of school—its demand for compliance—teaches us not to act in a friction-causing manner.

4. "No Child Left Behind" and "Race to the Top." The corporatocracy has figured out a way to make our already authoritarian schools even more authoritarian. Democrat-Republican bipartisanship has resulted in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, NAFTA, the PATRIOT Act, the War on Drugs, the Wall Street bailout, and educational policies such as "No Child Left Behind" and "Race to the Top." These policies are essentially standardized-testing tyranny that creates fear, which is antithetical to education for a democratic society. Fear forces students and teachers to constantly focus on the demands of test creators; it crushes curiosity, critical thinking, questioning authority, and challenging and resisting illegitimate authority. In a more democratic and less authoritarian society, one would evaluate the effectiveness of a teacher not by corporatocracy-sanctioned standardized tests but by asking students, parents, and a community if a teacher is inspiring students to be more curious, to read more, to learn independently, to enjoy thinking critically, to question authorities, and to challenge illegitimate authorities.

5. Shaming Young People Who Take Education—But Not Their Schooling—Seriously. In a 2006 survey in the United States, it was found that 40 percent of children between first and third grade read every day, but by fourth grade, that rate declined to 29 percent. Despite the anti-educational impact of standard schools, children and their parents are increasingly propagandized to believe that disliking school means disliking learning. That was not always the case in the United States. Mark Twain famously said, "I never let my schooling get in the way of my education." Toward the end of Twain's life in 1900, only 6 percent of Americans graduated high school. Today, approximately 85 percent of Americans graduate high school, but this is good enough for Barack Obama who told us in 2009, "And dropping out of high school is no longer an option. It's not just quitting on yourself, it's quitting on your country."

The more schooling Americans get, however, the more politically ignorant they are of America's ongoing class war, and the more incapable they are of challenging the ruling class. In the 1880s and 1890s, American farmers with little or no schooling created a Populist movement that organized America's largest-scale working people's cooperative, formed a People's Party that received 8 percent of the vote in 1892 presidential election, designed a "subtreasury" plan (that had it been implemented would have allowed easier credit for farmers and broke the power of large banks) and sent 40,000 lecturers across America to articulate it, and evidenced all kinds of sophisticated political ideas, strategies and tactics absent today from America's well-schooled population. Today, Americans who lack college degrees are increasingly shamed as "losers"; however, Gore Vidal and George Carlin, two of America's most astute and articulate critics of the corporatocracy, never went to college, and Carlin dropped out of school in the ninth grade.

Read More @ Alternet

***

Bruce E. Levine is a clinical psychologist and author of Get Up, Stand Up: Uniting Populists, Energizing the Defeated, and Battling the Corporate Elite (Chelsea Green, 2011). His Web site is www.brucelevine.net

Published on August 03, 2011 04:15

August 2, 2011

Xaveria Simmons: Thundersnow Road, North Carolina, 2010

During her fall 2010 residency at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, New York artist Xaviera Simmons met visitors and worked with Duke faculty and students. Her work was commissioned by the Nasher Museum for The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl. For her Thundersnow Road, NC project, Simmons created photographs of the North Carolina landscape and solicited musical responses from musicians such as Mac McCaughan of Superchunk, Tunde Adebimpe of TV on the Radio and Jim James of My Morning Jacket. The original songs were pressed onto a 12-inch record that is the soundtrack for her photographic installation.

Published on August 02, 2011 13:56

Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool

with Artist Barkley L. Hendricks, Art Historian Richard J. Powell, Curator Trevor Schoonmaker.

Published on August 02, 2011 13:37

Tera Hunter on 'Family Values' & 'Slave Marriages'

Op-Ed Contributor Putting an Antebellum Myth to Rest by Tera W. Hunter | The New York Times

WAS slavery an idyllic world of stable families headed by married parents? The recent controversy over "The Marriage Vow," a document endorsed by the Republican presidential candidates Michele Bachmann and Rick Santorum, might seem like just another example of how racial politics and historical ignorance are perennial features of the election cycle.

The vow, which included the assertion that "a child born into slavery in 1860 was more likely to be raised by his mother and father in a two-parent household than was an African-American baby born after the election of the USA's first African-American President," was amended after the outrage it stirred.

However, this was not a harmless gaffe; it represents a resurfacing of a pro-slavery view of "family values" that was prevalent in the decades before the Civil War. The resurrection of this idea has particular resonance now, because it was 150 years ago, soon after the war began, that the government started to respect the dignity of slave families. Slaves did not live in independent "households"; they lived under the auspices of masters who controlled the terms of their most intimate relationships.

Though slaves could not marry legally, they were allowed to do so by custom with the permission of their owners — and most did. But the wedding vows they recited promised not "until death do us part," but "until distance" — or, as one black minister bluntly put it, "the white man" — "do us part." And couples were not entitled to live under the same roof, as each spouse could have a different owner, miles apart. All slaves dealt with the threat of forcible separation; untold numbers experienced it first-hand.

Among the best-known of these stories is that of Henry "Box" Brown, who mailed himself from Richmond, Va., to Philadelphia in 1849 to escape slavery. "No slave husband has any certainty whatever of being able to retain his wife a single hour; neither has any wife any more certainty of her husband," Brown wrote in his narrative of his escape. "Their fondest affection may be utterly disregarded, and their devoted attachment cruelly ignored at any moment a brutal slave-holder may think fit."

He had been married for 12 months and was the father of an infant when his wife was sold to a nearby planter. After 12 more years of long-distance marriage, his wife and children were sold out of state, sundering their family.

Slave marriages were not granted out of the goodness of "ole massa's" heart. Rather, they were used as tools to keep slaves in line and to increase profits. Many slaves were forced to marry people they did not choose or to copulate like farm animals — with masters, overseers and fellow slaves.

Abolitionists and ex-slaves publicized excruciating details like these, but the world view of pro-slavery apologists like James Henry Hammond, a senator from South Carolina, could not make sense of motivations like Brown's. "I believe there are more families among our slaves, who have lived and died together without losing a single member from their circle, except by the process of nature," than in most modern societies, Hammond claimed. Under the tutelage of warm and loving white patriarchs like himself, slave families enjoyed "constant, uninterrupted communion."

Hammond's self-serving fantasy world gave way to reality during the Civil War, as slaves escaped in droves to follow in the footsteps of Union Army soldiers. Although President Abraham Lincoln had promised that he would not interfere with slavery in states where it already existed, he and his military commanders were faced with the unforeseen determination of fugitives seeking refuge, freedom and opportunities to aid the war against their masters. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler developed a policy of treating slaves as "contrabands" of war, inadvertently opening the door for many more to flee. In early August 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act, which authorized the army to seize all property, including slaves, used by the rebellious states in the war effort.

"Contrabands" became the first beneficiaries of a government appeal to military officers, clergymen and missionaries to marry couples "under the flag." The Army produced marriage certificates for fugitive slave couples solemnizing their marriages, and giving legitimacy to their children for the first time. But it was not until after slavery was abolished that marriage could be secured as a civil right. Despite resistance from erstwhile Confederates, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which extended the right to make contracts, including the right to marry, to all former slaves.

Why does the ugly resuscitation of the myth of the happy slave family matter? Because it is part of a broad and deliberate amnesia, like the misleading assertion by Sarah Palin that the founders were antislavery and the skipping of the "three-fifths" clause during a Republican reading of the Constitution on the House floor. The oft-repeated historical fictions about black families only prove how politically useful and resilient they continue to be in a so-called post-racial society. Refusing to be honest about how racial inequality has burdened our shared history and continues to shape our society will not get us to that post-racial vision.

***

Tera W. Hunter, a professor of history and African-American studies at Princeton, is the author of To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors After the Civil War.

Published on August 02, 2011 06:07

More Heart Than Swag: Otis Redding & Chuck D

from Public Enemy:

This is a polite respect call to the troops , to continue to inspire but reflect the people better. OTIS Redding was a humble country man from Macon Georgia who bought a jet to work in, not flash. He perished in that plane. Heres to hoping that the J & K supergroup can elevate the masses and try a little bit more to reflect OTIS's heart rather than swag, because they're too good to be less.

Published on August 02, 2011 05:55

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.