Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1070

July 23, 2011

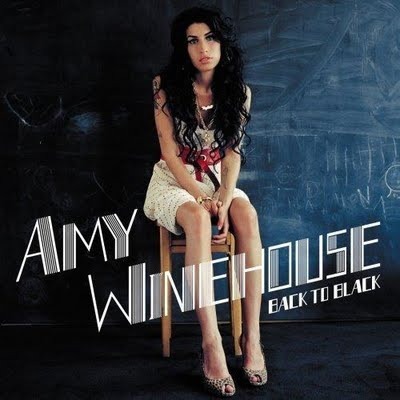

Amy Winehouse and Her Critics: Lines Lived Among the Lyrical Landmines

Amy Winehouse and Her Critics:

Lines Lived Among the Lyrical Landmines I stay up clean the house at least I'm not drinking.Run around just so I don't have to think about thinking. —Amy Winehouse, "Wake up Alone"

I wrote the following essay after reading Daphne Brook's review of Amy Winehouse in The Nation Online in September of 2008 when Amy Winehouse's album Back to Black was still a sensation lost by degrees to the shadow of her real-life foibles projected by the pop culture industry's (from tabloids to academic critiques) media machine. I came to Winehouse's work late, I considered her then and I consider her now one of the very finest writers and deliverers of "lyric" I'd come across in recent years. The following is the final third of a triptych essay I'd drafted titled "Evil Gal's Blues" that considered the lyric brilliance of Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington, and Amy Winehouse. Yes, I was looking for a fight. Right off, I'd heard something in the way Winehouse can (now, could) "live a line" that joined her to the work of these master-forebearers of her trade. Lyric. Now that she's gone on and formally joined Holiday and Washington and other too-briefly lit lyric torches, I thought it would be a good time to reconsider how Amy Winehouse sounded, at her best. Rather than gawking at her at her worst, I thought some people might be willing to consider her in her place, where I think she belongs, among other great lyric writers. Here's my piece:

*

"I keep thinking about the lessons of the human ear / which stands for music, which stands for balance—" writes Adrienne Rich in "Meditations for a Savage Child," from Diving Into the Wreck. She's meditating on the role of the ear, of hearing, and of language in trafficking between and charting terrains of who we are. She considers the physical structure of the ear : "the whorls and ridges exposed / It seems a hint dropped about the inside of the skull / which I cannot see." As one pushes one's listening back into the interior, as we all know, the identifications and distinctions between self/other (between whole grammars of this and that) begin to bend, flex, warp. Rich concludes the section observing : "go back so far there is another language / go back far enough the language / is no longer personal / these scars bear witness / but whether to repair / or destruction / I no longer know."

For you I was a flame

I want to suggest that, at bottom, the lyric is a device for pulling back these kinds of layers (in language, memory, experience) or suddenly piercing through them, a way of charting and summoning buried structures and putting them into the air. Obviously, various borders (which can be concrete in one level of experience or voice and which can become porous, and even vanish, in others) are blurred and crossed in this 'lyric' process. Others appear sharply focused often by the crossing as if transcendence pulled a hamstring and left one, then, across the border in denied territory. This kind of traffic can be disorienting and, as Rich notes, can bear ambiguous results (repair or destruction) to the traveler. But, what happens if the lyric traveler (as well as the audience) operates in proximity to sacrosanct, historically volatile borders? Seems the results could be confusing, even dangerous. This final section of "Evil Gals' Blues" charts just such lyric confusions and dangers (and, possibly, some that offer a sense of growth and repair) emanating from and swirling about the career of contemporary musician, singer and lyricist Amy Winehouse. Possibly, considering her work in close relation to its lyric pulse (and in relation to multiple lyric traditions with which she's aligned) might enable a new glimpse at what she's done, what she's undone, and what's she's provoked in response to her various "lessons [for] the human ear."

love is a losing game.

In her recent essay, "Tainted Love," about the ambiguous racial and gendered scurryings-about inflecting (infecting?) Amy Winehouse's voice, stage persona and personal life, Daphne Brooks displays many many things. One, she obviously knows more about the pop cultural cipher than I do these days. Brooks is seemingly mad at Amy Winehouse (isn't everyone?) about many things : unacknowledged and / or dishonored sources of her style; her style; her bad behavior off stage; the stage; her borrowed behavior on stage and her self-obliterative behavior off of it? But, is any of this a surprise? Maybe *that's* what—the repetition trauma—Brooks is—and seemingly so many others who care about popular culture are—upset about? I appreciate what Brooks writes. And she writes about many things: minstrelsy, vaudeville, the blues, Motown, Winehouse's racial affronts, her stage show, her cracker jack handlers. All with accuracy and aplomb and a healthy dose of rage.

Five story fire, yet, you came / love is a losing game.

What I'd like to do if I could is re-orient attention according to the rare things I hear in Winehouse's lyrics. Most centrally, the power of her writing and the way her lyrics—in the tradition of lyricists like John Keats, Billie Holiday, Hart Crane, Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, Dinah Washington, Marvin Gaye, Yusef Komunyakaa and others—involve frayed edges of her life and psyche. Even more, I'd like to point to Winehouse's gift for "living the line" in performances that (dangerously) blur the line between life and art in a way that communicates a turbulent, simultaneous sense of living and artistic flux at the border (among others) between becoming and unbecoming. So, this is an essay about art and the rough (largely interior but not necessarily personal) waters it swims on its way to us. Before that, some ground to clear.

One I wished I'd never played / oh, what a mess we made.

As with much I've been reading about Winehouse (admittedly, not an exhaustive survey), all of what Brooks writes is true and most of it a.b.c. gum stuck to the shoe of the popular culture that's steady stomping on Amy Winehouse. It's a formidable distraction. It has been a while since a performer of such talent has worn the shoe that stomps her with quite the intensity of Ms. Winehouse. Still, amid it all, I think Amy Winehouse is a real lyricist. One of the best I've heard. And, as happens in all true lyrics, registers of experience collide and the results in life can be as ugly as the results in song can be beautiful. Whatever—beautiful, that is—that means? Certainly, there are things to pick at about Amy Winehouse (easy target) and even easier to dart the barn-sized board of popular culture. Even easier than that to deconstruct historical popular culture where we don't share the blind place in the contemporary chaos that the performers occupy.

And, now the final frame / love is a losing game.

But, pinning sources of brilliant, surprising lyrical writing (and performance) is harder. In fact, it might be impossible. After all manner of hypotheses, Brooks ends up wondering whether all of the shenanigans isn't really about Winehouse's wanting "to be a black man." I guess that'll put her through changes. But, it seems like a distracting gesture. Has anyone wondered if much of Amy Winehouse's turmoil isn't also about her attempts to coexist with her powerful (verbal and vocal) lyrical gifts? As the lives of Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington show plainly, coexistence with intense lyrical talent has a well-earned reputation as risky (even more than risqué) business and a m.o. that matches Winehouse's life along the ever-blurrier line between on and off stage. Let's cover a little territory and then get back, briefly, to what's so overlooked about Winehouse's music. Namely, the music. And then let's give a moment's attention to the pulse-under-razor in some of her lyricism.

Played out by the band / love is a losing hand.

Obviously, Winehouse's style is begged, borrowed and stole(n). Doesn't everyone know that? She names Ray (Charles) and Mr. Hathaway in the rehab song. I haven't followed her around, but I'd guess it's no secret. Seems to me as I look around the University of Georgia campus where I work, young "white"--they and some of the world may think they're white, but they're not--men wouldn't even be able to say hello and shake hands without the guidance of black culture telling them to chin up and find a way to touch hands while staring thru (Shem style) not into each other's eyes. Cross-racial lyric gestures? Am I supposed to be mad at that? Ironically enough, I used to be mad at that! Maybe I still am. But, if they'd come up with surprising poems and songs about it, I'd be less mad at it. Maybe. But, it doesn't matter, the fact is that if you live on earth and have electricity (or someone you know does), you've been touched by the rhythms of black life in America.

It was more than I could stand.

And Winehouse's racist ditties (apparently, there's footage of her singing some offensive song to the tune of "Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes")? I hadn't heard them, doesn't surprise, don't want to hear them, really. By now, don't we all know that we ALL carry around brains full of racial slurs about —"our own," whatever that means, and—other races in our heads? When a (literally) slurring addict like Winehouse, or a repeat offender like Jesse--cut his nuts off--Jackson, or a Spanish--chinky-eyed--basketball team lets out in public, it's an offensive wave. Sure. But, I've heard and seen it all before and so has everyone else.

Love is a losing hand.

And the hoopla and politics and dope and money swirl in and around Amy Winehouse in ways we've seen before too, right? Don't they? One of Daphne Brooks's criticisms of Amy Winehouse is that she's desecrating dignified images and the behavior of performers who crafted images of black people compatible with Dr. King's vision of a racially inclusive America and upon whose musical legacy Amy Winehouse borrows heavily. But, I'm not sure we can honestly look at sources of lyrical brilliance for models of good behavior. Can we? Maybe the Motown girl groups. Maybe. But, don't let's look to Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday or Mahalia Jackson for our models of personal behavior, ok? Is *this* why Whitney Houston, Chaka Khan, Natalie Cole, Phyllis Hyman, Alicia Meyers and on and on and on get left off the well-behaved list? Did they desecrate the Dream, too? In "Baby Get Lost," Dinah Washington nods to the moral sense, but she's too busy to follow through. She sings : "I'd try to stop you cheating but I just don't have the time. Cause I've got so many men that they're standing in line." Don't keep listening, one of the men is a seven-foot tall dentist named "Long John."

Self-professed profound / til the chips were down.

Chaka Khan sang "I'm Every Woman," I guess, if one's going to be every woman, a few might not be the ones to invite to the in-laws for the howdy dinner? Amy Winehouse is clear about that as she is, in her brilliant blues, "Stronger Than Me," about the ambiguities of a woman's desire freed of family obligations : "I'm not going to meet your mother, anytime." Maybe she's felt a dose of her own "look who is [not] coming to dinner" blues? In South London, it's more than possible.

Though you're a gambling man / love is a losing hand.

Is it (again!) the role of music to affirm black dignity through respectability? Is it the only role? First, as W.E.B. Du Bois noted, and as Billie Holiday noted from her childhood in Baltimore, and in a way that echoes many scenes in my own life, many 'respectable' black folks might not have been eager to rub elbows with someone like Amy Winehouse. No home training. Who knows? Second, come to that, let's don't (via time machine) upload 20 hours worth of day-in-the-life, realtime footage of Billie Holiday in action, ok? F and N bombs for all, she'll make your toenails curl up. Is this news? And before we go washing Barry Gordy's feet in hot oils, now, if the Motown men and women *were* prodded into respectability (the ambiguities about which poets like Melvin Dixon, Cheryl Clarke and others have long had lots to say) for the Dream, and they were, no doubt, they were also prodded—flipped hair, pearls, diction lessons and all—that way for the cross-over cash. Why else move the operation to a city named for los angels and dedicated to covering the globe with celluloid delusions. Or was that just so Aretha could profile with the pink drop-top in January?

Though I battle blind / Love is a fate resigned

Anyway, cross-racial heresy and the poisoned-privacy meets media-frenzy dilemma are all old friends of pop talent, aren't they? Billie Holiday did a year and a day for it. No, scratch that, she did life. And, death. At least the spectacle is a friend of the agents and labels with Their Eyes on the News Cycle. Some artists handle it better than others. And, some make a bi-zillion $ (for someone) whilst it happens. And, I'd guess (though I haven't actually done the research) it's probably obvious that (the miss-taken for) "white" train wrecks do make a lot more dough (for someone) than the black ones do. Legions and generations of black blues and jazzmen and women who were geniuses and train wrecks (and some who lived dignified anonymous lives and some veering from one to the other and back) did it for free! Call Sharpton.

And the memories they mare my mind.

But, even after the march and the Tom Joyner spot, none of this seems new to me at all. At bottom, it's an unavoidable ebb and flow, like sunrise and set, in a fundamentally delusional culture.

Love is a fair design.

But, still, why Amy Winehouse as a lens for all this interesting, but re-treaded, critique? Most of Brooks's essay (and many others about Winehouse) is as interesting without Amy Winehouse as it is with her in it. Post Modern? I once had a friend who informed me that she felt no hesitation blasting the film Hustle and Flow even though she hadn't seen it. My position was that it did something for black, southern, un-respectible male life similar to what a Cézanne still life did for peaches. Then again, rightly and / or wrongly, the way one feels about that would fluctuate depending upon one's relationship to peaches in the world. Nonetheless, unlike 'cultural moments,' art insists (and we on its behalf as it does on ours) that its existence be seriously reckoned with. Anyway, I guess the fact that Amy Winehouse's voice makes almost no appearance at all in much of this critique would be perfectly fine if Winehouse was, say, a painter. But, a singer?

Oh, over futile hours / and laughed at by the gods

So, if the voice is basically absent, is it just the buckets of money, media play, and her private (made pornographically public) demise? Again, apart from youtube access, is this new? It's not like the minstrel tradition and black musical influences are an esoteric discourse hidden high on a mount. And one can, as we know, hide in plain view. As poet George Oppen lamented (strangely), you couldn't escape the voice of black music if you wanted to. So, why Amy Winehouse? Well, what about talent? Brooks's writes : "Winehouse has been lauded for essentially throwing [Billie] Holiday along with Foster Brooks, Louis Armstrong, Wesley Willis, Megan Mullally's Karen on Will and Grace, Moms Mabley and Courtney Love into a blender and pressing pulse." Ok, cool, but that's not how music gets made, it's not how lyrics get written. When the chips are down, a person does that and during the key moments when it happens, they're as good as deaf and blind. If there was a button to push, there'd be a million Amy Winehouses. There aren't.

And now the final frame / love is a losing game. Thank you.

And, too, maybe it's like Ezra Pound said of the folk-ballad scholarship that basically proved that "Homer" wasn't an unprecedented individual. In fact, there were hundreds of Homers. It was a whole culture of Homers. True. And, Pound : "but that doesn't explain why this 'Homer' is so much better than everyone else."When we say culture, sometimes, we are also talking about art, right? Music. So, why is "aesthetics" (sound) and "lyrics" (writing) and lyricism (apt performance) missing from the discussion of Amy Winehouse? Maybe it's not. But, if you think it is, keep reading. I'm getting there.

What are you going to do? This is a tune "Stronger Than Me"

Aesthetics. The thing missing from all this Amy Winehouse stuff, for me, is the brilliance of her writing and the crushing way she can (and sometimes does) deliver a line. All due import to period, race, nation, racism, in fact and even so, shockingly, frighteningly (for her), like Billie Holiday, Amy Winehouse seems to be able to write it out and then "live a line" in a song. It's about how to sing with one foot in the song and one foot in the world and be both places and neither at the same time. In other words, you have to be who you are and who you're not. It's tough to do that. It's tough to know that the bottom of who you are has little predictable to do with who you think (let alone who other people think) you are. That's the lyric.

In Stephen Hero, James Joyce called the lyric "a simple liberation of a rhythm." What a novelist. Truth is that it's a complex simplicity and, from the evidence, a liberation—like so many—with deeply ambiguous (destruction or repair and, in relation to what, which is which?) consequences. In other words, it's a real risk. Like James Baldwin wrote of his days in the pulpit, for all the preparation and deceit involved, "there were times when it seemed I was really carrying the Word," when, as he explained, the speaker / singer all of a sudden, by whatever accident, testifies to his / her own experience and to the audience's experience at the same time. We reach a language somewhere hidden in us that, as Adrienne Rich writes, is "no longer personal." But, by this point we can clearly see that that's not quite it, either. The lyric voice is, indeed, beyond the personal, but at the same time, it's not not personal, either. Is there a word for that? In my experience, when the beyond but not not personal blurs inter or intra (or the blurs the distinction between intra- and inter-racial) radical dynamics, there's a word for that. Trouble.

You should be stronger than me / You been here seven years longer than me

That's the crux of the "lyric" tradition, a map of the immediate simultaneity of otherwise divergent interior and public lives. Tangents. Lyrics. Ever looked at a Francis Bacon tryptic and seen your portrait? Millions have. It's the opposite approach to an epic condition. The route to the "universal" leads through things that aren't things about the most intensely private reaches of our beings. The (counter) logic goes like this : if you can touch that private thing that's so private it's a secret from yourself, that's yours and yours alone, and if you can voice that thing, other people will see themselves there. That is to say, if you can really get alone, you realize you're not. Go figure. And, then get ready.

Don't you know you're supposed to be the man.

And, yes, and with whatever other stuff about Amy Winehouse, with all of it, the child can do that. She does do that. Not every performer can do that. No one really knows how they do that. Smokey Robinson went into Marvin Gaye's house while he was writing What's Going On, Marvin said, "Smoke, I ain't writing this, man, God's writing this." Maybe, maybe not. But it wasn't really "Marvin," either. And, Marvin knew that and it was tough for Marvin to know that. With studio time left over, they asked Billie Holiday if she knew any "sayings" that would make a good extemporaneous blues. Resisting the "down home" implications, the sophisticated Lady said, no. Then after a few moments, she said, well, there's that saying "God Bless the Child. . .". But the saying isn't the lyric. Billie Holiday made the lyric from the saying, there on the spot. She pinned it to a melody and injected it with . . . well, with what? Well, with something unknown (to her) in herself, but that doesn't really narrow it down. And, then there's how?

I pale in comparison to who you think I am.

There's no map to the origins (though it seems to be close to some pain center in the brain of the gifted/afflicted) of this talent and there damned sure isn't an etiquette guide for how to handle that gift. A list of "lyricists" from John Keats to to Marvin Gaye, to Ms. Winehouse's Mr. Hathaway to. . . won't necessarily produce a viable group of people to run for Senate or to affirm anyone's respectability. Then again, either will any other 100 people randomly selected (including, obviously, the present Senators). That's the delusion.

Cause you always want to talk it through, and I don't care.

The lyricists affirm, though, they affirm plenty : we're here; this is who we really are. They leap into the dark and say, "if it's there in me, it's there in us all." Is there any real dignity—leave respectability to the side—without that affirmation? James Baldwin told Studs Terkel, "there's a division of labor in the world. . . my job is to imagine the private life. Not mine, yours." Billie Holiday sings in her lover's ear in "Long Gone Blues" : "Aw, you trying to quit me baby but you don't know how." How do we know she's right?

I always have to comfort you, when I'm there.

Lyric. Repair and Ruin. In 1983, at the NBA All-Star Game, Marvin Gaye sang the United States as close as it's ever been (in my ear) to a truly "lyric Anthem" of itself. It was as if he'd been possessed by the ghost of Lester Young—who was always possessed by the presence of Billie Holiday and vice versa. Listen to Marvin's Anthem against, say, Lester Young's "I'm Confessin'." Anyway, Marvin was very respectable. Well dressed, clean, with dark shades on to hide how hopelessly fucked up he was. In his voice, the place—this is Reagan's America—actually sounded like a place to live, not a prison, not a Nepalm strike, not a suburb, not a cliché or an abstraction to be defended through extermination of "terror" and other murderous, delusional objectives to achieve. I listened then and I listen—via youtube—now and I think, I could live there. And I watch Marvin's chin bump the mic and see his knees buckle to near-collapse and his face crack open into a vague plea when he belts "La-and of the free. . .". I think, shit, I do live there. And, I wonder what color flashed behind those shades when he whispers "Oh lord" (just off the mic) at the close of the song. And he did it in Philly, where Billie was pinned to the narcotics charge that got her sent away for a year and a day. She came back a year later, with Decca, singing "Ain't Nobody's Business if I do. . ." and never played in a New York City jazz club again. Life. It's nobody's business. As for Marvin, he was dead inside a year. Anyway, enough lyric history.

But, just what I want you to do, stroke my hair.

So, yes. That Racial Apartheid American Style and sheer terror of life on the denied territory athwart Jefferson's disease-and-genocide depopulated, slave- state dream of a "tabula rasa with inalienable rights" has forced (some) black folks to show out, dress well and behave better than that no matter the hell inside marks an important line in the sand. Whew. It's a valuable principle of coherence for black culture with its own dissident tradition (why people like Robert Williams, Malcolm and Baldwin weren't at the March on Washington). So, is the point that Amy Winehouse should mime *that* part of the culture as well as whatever she already has in the blender? Sure, why not? If she gets to grow up, she might. She's 25 at light speed.

Oh, I forgot all of young love's joys.

Cursed blessings abound, changing costumes, all the while sharpening their teeth. My ipod could hold enough itunes songs to empty my retirement account. At this rate, the bank can give my mortgage, my student loans and applications for Chinese passports to my kids. But, art lasts.

I feel like a lady and you're my ladyboy.

Lyrics. Aesthetics. I've listened to plenty minstrel acts (not all of them white) and few of them "live a line" in a song like Ms. Winehouse can. Strictly speaking, maybe it's not *her* (moat diggers abound) life she's living in these songs; that's true of every autobiography we have. Imagined. Lives come apart and come back together in the turbulence of an imagination. Alberto Giacometti would spend hours sculpting or painting his model's face (his brother, his wife, friends) and then go to dinner (usually around 3 am) with them and claim that he didn't recognize them at all. Shit gets loosed in a lyric. Have we met? Beckett found the plays in the abyss, wrote them in French, and then translated them back into English. Identities loosed, borders be damned. Stevie Wonder is (and isn't) Steveland Morris. Yusef Komunyakaa isn't (and is) whomever he was by whatever "misfitted"name growing up in Louisiana. Ruth Jones in Alabama, Dinah Washington in Chicago. Someone little black, Irish-Catholic girl in Baltimore by the name of Fagan, someone else (and not) sings "Moanin Low" with Lester Young whispering in her ear. Who are they when they sing what they sing? Who are we when we hear them? Cause if they're not exactly who they are, then are we. . ? You see, this lyric business is disturbing stuff. Maybe that's why it's left out of the culture wars. It won't choose sides. It won't represent.

You should be stronger than me / but to stay longer than frozen turkey.

Racial, ethnic borders in a riven, violent world imperil people's lives. No matter, the imagination won't abide these borders and identities fracture in creative work (the Yoruba word for tradition translates as "fork in the road"). Even de-Frosted, there really isn't any being one traveler. As DuBois knew way back yonder-when and as Michelle Cliff's brilliant new book, If I Could Write This In Fire, shows again and again, being (what George Oppen called) 'numerous' in America is ever an inter-racial, fraught, reality. All artists aren't well studied in matching one dimension of experience (of a life) to the others. But, their skill and foibles can illuminate otherwise invisible lies and perils and, hopefully, otherwise invisible boons and pleasures and truths. As an artist, while one's busy tripping the invisible beams of the alarms (which is never the point of a piece, much less a life, really), it's hard to tell which is which. Enter, critics.

Now, why you always put me in control / when all I need is for my man to live up to his role.

In the end, who knows just whose life (or lives and how many) sounds (sound) in Amy Winehouse's mouth? But, in the lines she lives, she's made it hers better than crowds and crowds of others. Here and there on the records it happens. The critics and audiences know this. And, by obsessing (on Jezebel and other net rags and elsewhere) on the distractions, it seems the audience and critics seem to have as much trouble dealing with her gift as she does. T.S Eliot wrote that the perfect critic must first "submit to the work," get eye to eye and toe to toe with the art. Is anyone doing that? When I try it with Ms. Winehouse's work, it's moving and scary.

You always want to talk it through, and I'm ok / I always have to comfort you everyday.

It happens on the records, but it happens better on those youtube performances (with live acoustic guitar--yes, black men in both cases--accompaniment) of "Love is a Losing Game" and "Stronger Than Me." "Stronger than Me" is so "wrong" it works in the (black) signifying tradition over gender roles. The woman's voice complains that the man should be stronger than she is while she distills her needs and voice into crystal clear beams of being. Works for me anyway. Gender reversals and behind the scenes brought into the light : "You always wanna talk it through, and I don't care. I always have to comfort you when I'm there / but just what I need you to do, stroke my hair." She taunts "I feel like the lady and you my ladyboy / you should be stronger than me. . ./ why you always put me in control." Curse of the superwoman myth belied and even a little cross-racial im-posturing revealed : "I pale in comparison to who you think I am." Standards quoted and coda attached : "You don't know what love is / get a grip." Is that song that far from "Don't Explain" or "Long Gone Blues" or Dinah Washington's "I'm a girl who blew a fuse"? Amy : "Don't you know you're supposed to be, the man?" Billie : "Ah, you're trying to quit me baby but you don't know how." Maybe I'm too far gone, but I'd love to hear Hot Lips Paige in there with a plunger mute filling in windows with Ms. Winehouse. Keep the Dap-Kings. I don't need the retro hoopla. Give me the lyrics. At heart, she's a solo songstress, lyrics like razors, symmetrical as Sushi, in relation to which so much of the culture looks and sounds like Botox'd butcher meat.

This what I need you to do / are you gay?

Going under. At the Mercury Awards in 2007, that version of "Love is a Losing Game" is classic concert songstress lyricism. The tune swims the whirlpool like a bird with a broken wing. Afloat, for now. And, Ms. Winehouse behaved herself even if her tattoos didn't. Maybe it's borrowed straight from Billie Holiday at La Scala? Or stolen. Either way, it's the best Sade song I've seen performed in years. And maybe that is a crime but it's true. Because he was there at those pianos with Billie Holiday at the end, I'd love to ask Mal Waldron what he hears in this performance. That "no longer [but not not] personal" thing I hear living those lines in Amy Winehouse's voice probably didn't announce itself when it appeared. Likely, it knew her before she knew it. Could she handle it better? Yes. Who knows? I don't. Would I have? Am I stronger than Amy Winehouse? Was I when I was 25? The questions are meaningless. Or maybe they're not. But, they shouldn't overshadow the brilliant lines the woman's living in her work.

He said the respect I made you earn / I thought you had so many lessons to learn / I said you don't know what love is / get a grip.

Take a few reads through the line above. How's that for a younger (supposed to be white?) woman turning around the head-trip rap of a seven-years older (presumably black) man? Where'd she run into that line do you suppose? Where'd she get that lyrical ground to stand on? And, what did that cost? In any case, if she stole it upfront, seems like she's paying for it (or paying for something) now. She sings, in "Love is a Losing Game," about the "memories that mare my mind," and she rips the word m-i-n-d apart and into the sound (if it makes sound) of tearing flesh. If tearing flesh doesn't make a sound, it does now. As Adrienne Rich put it in "Meditations for a Savage Child," another "lesson of the human ear." And, new. Lyric brilliance. Always dialogic, always, ours. That is new. Like Pound said about real poetry, "it's news that stays news."

I'm not going to meet your mother, any time / I just wanna grip your body, over mine / now, please tell me why you think that's a crime?

And, watch with your ears or (via youtube) listen with your eyes as she nails "think" to the ear in the lens of the camera. In "Uses of the Blues," James Baldwin recounts a story of Miles Davis giving an addicted and broke Billie Holiday $100. And someone said to Miles, "man, you know she's going to go buy dope with it." And Miles : "Man, haven't you ever been sick?" Which, in whatever imperfect way, was Miles saying two things : don't fool yourself, it could be you; and, go easy on her, ok? Let's us in her audience (critics and especially professors!) go a little easy on the poet, Amy Winehouse. She's in a tumult and she doesn't know the way in or the way out and, if others like her are any guide and when push comes to shove, she's going to have to find the way on her own. And, by that, by the logic of the "no longer [but not not] personal" lyric, she'll do some of that traveling for (if not with) us. I'm pulling for her.

You should be stronger than me

***

Ed Pavlić's most recent books are But Here Are Small Clear Refractions (Achebe Center, Bard College, 2009), Winners Have Yet to be Announced: A Song for Donny Hathaway (UGA P, 2008) and Labors Lost Left Unfinished (UPNE, 2006). His other books are Paraph of Bone & Other Kinds of Blue (Copper Canyon P, 2001) and Crossroads Modernism (U Minn P, 2002). His prizes include the Darwin Turner Award from African American Review, The American Poetry Review / Honickman First Book Prize, and the Author of the Year Award from The Georgia Writers Association. He teaches Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Georgia at Athens.

Published on July 23, 2011 20:00

July 21, 2011

What Locked-Out NBA Players Can Learn from the Negro Baseball Leagues

What Locked-Out NBA Players Can Learn from the Negro Baseball Leagues by Mark Anthony Neal | The Atlanta Post

Deron Williams' recent announcement that he was planning to play abroad during the NBA lockout with the possibility that many other NBA stars are also considering doing so, highlights the successful globalization of the NBA; it is one of the world's most recognizable brands. But as David J. Leonard recently suggested, "Whereas the NBA hoped to cultivate and capitalize on stars from China, Germany, France, Brazil and elsewhere," and market them to global fans, "it has been African American stars that have captured the hearts and minds of many global fans." Leonard notes, the NBA's desire for expansion has unwittingly given the leagues' players—80% of whom are of African-descent—bargaining leverage in the midst of an owners' lock-out.

NBA players have long been in a unique position; with regards to the NBA. the players exist as both the labor and the product, and despite the escalation of players' salaries in comparison to a generation ago, their labors have primarily increased the coffers of the league's owners. In contrast to their capacity to generate wealth for the owners and commissioner David Stern (whose job is to advocate on behalf of the owners), the players themselves have very little input in the basic affairs of the league (i.e. salary-caps, dress codes, minimum age limits, etc).

Given their role as the NBA's primary commodity, the question is not whether NBA players should play in Europe or elsewhere during the lockout, but whether the players should think about creating a professional league of their own that would maximize their labor, economic value and provide a legitimate alternative to the NBA. If the players were to look for a model, there is no better one than the Negro Baseball League.

When Moses Fleetwood was released by the Syracuse baseball team in 1889, he became a historic footnote: the last African-American to play in Major League Baseball until Jackie Robinson broke through the so-called "color line" in the spring of 1947. Fleetwood and many Black players until Robinson were subject to an unspoken decision by a cabal of Major League owners and players to ban Black players from the league. In effect the owners locked-out some of the best American baseball players of the early 20th century.

Read the Full Essay @ The Atlanta Post

Published on July 21, 2011 20:27

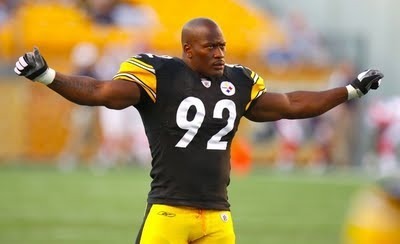

"No Dad at Home:" James Harrison, Colin Cowherd and the Case Against the Black Family

"No Dad at Home:"

James Harrison, Colin Cowherd and the Case Against the Black Fami

ly

by David J. Leonard |

NewBlackMan

"No Dad at Home:"

James Harrison, Colin Cowherd and the Case Against the Black Fami

ly

by David J. Leonard |

NewBlackMan

In a recently published article in Men's Journal, James Harrison questions the fairness and the administrative philosophy adopted by commissioner Roger Goodell. Referring to Goodell as a "crook," "puppet," "dictator" and a "punk" (among others things), Harrison problematizes the ways in which race operates within the NFL. "Clay Matthews, who's all hype — he had a couple of three-sack games in the first four weeks and was never heard from again — I'm quite sure I saw him put his helmet on Michael Vick and never paid a dime," notes Harrison. "But if I hit Peyton Manning or Tom Brady high, they'd have fucked around and kicked me out of the league." And: "I slammed Vince Young on his head and paid five grand, but just touched Drew Brees and that was 20. You think black players don't see this shit and lose all respect for Goodell?"

In a lengthy piece, entitled "Confessions of a Hitman," Harrison discusses a myriad of issues. Yet, his comments about the commissioner, and his references to racial inequality in the punishment of players, have not surprisingly prompted the most widespread media commentary and condemnation. For example, Gregg Doyel, with "Goodell is a strict disciplinarian, but he's no racist," scoffed at the claim the Goodell is a racist or even that he treats black players differently/unfairly (he and others may want to read the work of Herbert Simmons and Vernon Andrews – here is a second piece by Andrews).

Goodell runs his league the way strong parents run their family: With rules, with parameters, with discipline. No shortcuts. No excuses. Tough love all the way, and if the players don't like it, well, it happens. Does a 16-year-old like it when he sneaks out for a night of drinking, gets busted, then gets grounded for three months? No, the teenager doesn't like it. Shocking

Building upon this argument during a discussion about Doyel's piece, ESPN's Colin Cowherd took to the air to recycle longstanding arguments about black families, single-mothers, absentee fathers, and the purported cultural shortcomings of black America.

Here is something that is interesting, if you look at basic metrics or numbers in this country. 71% of African Americans no Dad at home; no disciplinarian. Fathers are often louder voice, the disciplinarian. Many of those kids don't grow up with a dad, raised by mom, sister, aunts, nieces, uncles whatever.

They go to college where they are stars. And basically even their college coach, as we saw with Ohio State, pretty much lets the stars run the program. The NFL is one of the first places where many star players finally see discipline. Finally have an authoritative male figure – buck stops here, I will make all the calls, you will not get an opinion.

This was not the first time Cowherd talked about black families in relationship to sports, having questioned John Wall's leadership abilities because of his limited relationship to his father (his father was incarcerated during Wall's childhood, dying of liver disease when Wall was age 9).

Let me tell you something: I'm a big believer, when it comes to quarterbacks and point guards. Who's your dad? Who's your dad? Because I like confrontational players, I don't like passive aggressive. Strong families equal strong leaders. Talent? Overrated. Leadership? Underrated. And you can say, well, Colin, can you just go out and say anything crazy and get people to e-mail. That's not the point. You wouldn't e-mail if I was an idiot, because you wouldn't listen to the show. You listen to the show because we make good points.

I simply have a different opinion than you do on John Wall. I like the character of Derek Fisher, the rebounding and distribution ability of Rajon Rondo, that's what I like. That's what I want from my point guards. You celebrate the assists more than the buckets.....I know he's great. So don't confuse [me saying] John Wall's no good. No, John Wall's an A talent. I don't think he's ever gonna be an A win-championships point guard.

In both instances, the efforts to recycle the Moynihan report, to define father as natural disciplinarian and mother's nurturing, to link cultural values to family structures, and to otherwise play upon longstanding racial stereotypes, is striking. However, I would like to reflect on his recent comments in a substantive way.

First and foremost, the idea that 71% of black children grow up without fathers is at one level the result of a misunderstanding of facts and at another level the mere erasure of facts. It would seem that Mr. Cowherd is invoking the often-cited statistics that 72% of African American children were born to unwed mothers, which is significantly higher than the national average of 40 %. Yet, this statistic is misleading and misused as part of a historically-defined white racial project.

First and foremost, child born into an unmarried family is not the same is growing up without a father. In fact, only half of African American children live in single-parent homes. Yet, this again, only tells part of the story. The selective invoking of these statistics, while emblematic of the hegemony of heterosexist patriarchy, says very little about whether or not a child grows up with two parents involved in their lives. According to the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a sizable portion of those children born to single mothers are born into families that can be defined as "marriage like." 32% of unmarried parents are engaged in 'visiting unions" (in a romantic relationship although living apart), with 50% of parents living together without being married. In other words, the 72% says little about the presence of black fathers (or mothers for that matter).

Likewise, this number says very little about the levels of involvement of fathers (and mothers), but rather how because of the media, popular culture and political discourses, black fatherhood is constructed "as an oxymoron" all while black motherhood is defined as "inadequate" and "insufficient." According to the introduction for The Myth of the Missing Black Father , edited by Roberta L. Coles and Charles Green,

It would be remiss to argue that there are not many absent black fathers, absence is only one slice of the fatherhood pie and a smaller slice than is normally thought. The problem with "absence," as is fairly well established now, is that it's an ill defined pejorative concept usually denoting nonresidence with the child, and it is sometimes assumed in cases where there is no legal marriage to the mother. More importantly, absence connotes invisibility and noninvolvement, which further investigation has proven to be exaggerated (as will be discussed below). Furthermore, statistics on children's living arrangements also indicate that nearly 41 percent of black children live with their fathers, either in a married or cohabiting couple household or with a single dad.

Countless studies substantiate the fallacies that guide claims about absentee black fathers. For example, while black fathers are the least likely to be living with or married to the mother, they are much more likely to be involved and engaged with their children.

For instance, Carlson and McLanahan's (2002) figures indicated that only 37 percent of black nonmarital fathers were cohabiting with the child (compared to 66 percent of white fathers and 59 percent of Hispanic), but of those who weren't cohabiting, 44 percent of unmarried black fathers were visiting the child, compared to only 17 percent of white and 26 percent of Hispanic fathers (in Coles and Green).

In total, Cowherd misrepresents reality, once again recycling a narrative about absentee black fathers and ineffective black mothers.

Second, the absurd "commentary" plays upon the idea that white power, the power to discipline and punish, reflects a level of benevolence, kindness, and a desire to save and help the otherwise helpless black child. Of course, this embodies the longstanding idea of the White's Man Burden. In 1899, after U.S. victory during the Spanish-American War, the British poet Rudyard Kipling famously coined the phrase "the white man's burden" to describe the responsibilities that reside with whiteness: a burden and obligation to teach and civilize the world's barbarians. Albert J. Beveridge, a senator from Indiana, celebrated the "white man's burden" as a noble mission and part of God's master plan to bring civilization to the entire world:

Mr. President, this question is deeper than any question of party politics; deeper than any question of the isolated policy of our country even; deeper even than any question of constitutional power.. It is elemental.. It is racial.. God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration.. No! He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns.. He has given us the spirit of progress to overwhelm the forces of reaction throughout the earth.. He has made us adepts in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples.. Were it not for such a force as this the world would relapse into barbarism and night.. And of all our race.. He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world.. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man.. We are trustees of the world's progress, guardians of its righteous peace.. The judgment of the Master is upon us: "Ye have been faithful over a few things; I will make you ruler over many things.

It is clear that Cowherd sees Roger Goodell as following in these historic footsteps, bring civilization, leadership, discipline, and maturity to NFL and NBA players, who in his mind lack the requisite values because of the failures of their families.

Finally, the demonization of NFL and NBA players through the deployment of longstanding stereotypes of black families demonstrates "the significance we have placed in American society, and the black community specifically, on the relationship between fathers and their sons and on fatherhood and masculinity" (Neal, 111-112). Reflecting on the ways in which black masculinity, black femininity, and black families (blackness) are imagined and conceived within contemporary American discourses, Neal highlights the ways in which black fathers are rendered as absent and a source of problems for the black community within political/academic circles and popular culture projects. "Constructions of deviant sexuality emerge as a primary location for the production of these race and class subjectivities," writes Micki Mcelya in Our Monica Ourselves: The Clinton Affair and the National Interest . "Policy debates and public perceptions on welfare and impoverished Americans have focused relentlessly on the black urban poor – blaming nonnormative family structures, sexual promiscuity, and aid-induced laziness as the root cause of poverty and mobilizing of welfare queens, teen mothers, and sexually predatory young men to sustain the dismantling of the welfare state" (2001, p. 159).

Whether in popular culture or in the news, during sports telecasts or talk radio, black fatherhood and motherhood are ubiquitously cited as the cause of (national) problems or as an issue that young black males have to overcome. Cowherd falls suit, blaming the bogeyman and woman – absent black fathers and ineffective black mothers – for the problems facing the NFL, all while celebrating the efforts to police and punish as necessary fathering from their white daddy.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on July 21, 2011 20:19

Marc Lamont Hill: Why We Must Stand in Solidarity with the Pelican Bay Prisoners

Why We Must Stand in Solidarity with the Pelican Bay Prisoners by Marc Lamont Hill | Philadelphia Daily News

FOR NEARLY three weeks, inmates at Pelican Bay State Prison, in California, have been on a hunger strike. They plan to continue until officials agree to improve the conditions and prison policies.

Contrary to what prison officials have suggested, the prisoners' demands are far from numerous or extravagant.

To the contrary, the inmates have made five reasonable requests: individual accountability, so that entire groups (or races) aren't punished for the acts of one person; abolishing the policy that forces prisoners to snitch (thereby risking their lives) in order to avoid punishment; ending long-term solitary confinement, a practice that has been deemed torture by the United Nations; no longer withholding food as punishment; and providing reasonable programming and privileges, such as being allowed to have one photo per year.

I stand in solidarity with them. And so should you.

In Pelican Bay, and nearly every other prison in the country, inmates are beaten, raped, tortured and denied their constitutional rights. As prisons continue to expand at a rapid pace - Pennsylvania's prison spending grew by another 10 percent this year - these problems are becoming more prevalent and extreme.

At this point, many of you are rolling your eyes in disgust. You may even be asking, "Why should I care about how murderers and rapists are treated?"

First of all, the majority of prisoners are not there for violent crimes, nor are they even threats to society. Most are incarcerated due to crimes related to the failed War on Drugs, such as simple drug possession, petty theft and parole violations. More often than not, these are people who would not be incarcerated if they could have afforded to live in a better neighborhood or hire a better lawyer.

These are people who belong in rehab or mental-health facilities rather than buried in cages. The suffering they incur in prison only exacerbates their problems, making them more likely to commit crimes again.

Regardless of a person's crimes, however, no one deserves to be raped, tortured, starved or otherwise mistreated in prison. But, sadly, this is exactly what happens every day. Unfortunately, the abuse of prisoners goes largely unaddressed because of our refusal to see prisoners as people.

Consider, for example, all the jokes that are made in movies, TV and everyday life about prison rape. These jokes are rooted in truth, as nearly 2 percent of all U.S. inmates are raped while incarcerated. Such humor can be considered "funny" only if the people being hurt are not understood as full human beings.

Given this general lack of regard for prisoners, there is little political motivation to protect their rights. In fact, most politicians earn their stripes by imposing draconian and inhumane public policies, like the Crime Bill of 1994 or the various state-level three-strikes laws.

Even well-intentioned "progressive" politicians are reluctant to advocate for inmate rights because they fear that their opponents will label them "soft on crime."

Also, despite the fact that most inmate demands are both basic and reasonable, the popular media has made them appear frivolous and counterproductive. For example, in the 1990s, many news shows spread ridiculous lies about inmate lawsuits, such as the urban legend that an inmate sued a prison because he received chunky instead of creamy peanut butter.

The popularity of such tall tales greased the pathway for the creation of the Prison Litigation Reform Act - signed by Democratic President Bill Clinton - which has essentially closed the courthouse doors to inmates looking to redress various forms of abuse.

This is why it is important for us to strongly and publicly support the courageous hunger strike at Pelican Bay.

If our nation is truly committed to the idea that prisons are spaces for rehabilitation rather than mere punishment, we must create environments that are more humane, safe and productive. We must advocate for the rights of all inmates, regardless of what we think about their crimes. We must stand in solidarity with the brothers of Pelican Bay, and encourage other inmates to do the same.

***

Daily News editor-at-large Marc Lamont Hill is an associate professor of education at Columbia University. Contact him at MLH@marclamonthill.com.

Published on July 21, 2011 09:24

Robert Biko Baker: Inspiring Activism

from The Atlanta Post

Activism is not just born, but is something that is nurtured and inspired. Robert "Biko" Baker, the executive director of the Young Voters Education Fund (LYVEF) is all too familiar with the challenges and rewards of fostering activism and political participation amongst youth. Through his work, he has pushed the importance of voting and worked to inspire urban youth to get active and involved in the changes that they want to see. Here, he talks to The Atlanta Post about LYVEF.

Published on July 21, 2011 09:11

July 20, 2011

Locked Out and Demonized: Challenges Facing the NBA's Black Players

Locked Out and Demonized:

Challenges Facing the NBA's Black Players

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackman

Locked Out and Demonized:

Challenges Facing the NBA's Black Players

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackman Deron Williams made it official, signing a contract with Besiktas, a top tier team in Turkey. While not the first NBA player to sign a contract as a result of the lockout, he is clearly the most high profile (superstar) to do so thus far. Others may follow suit, with Kobe Bryant, Dwight Howard, Kevin Durant, Rudy Gay and Stephen Curry all noting interest in the prospects of playing overseas. Having already written on the larger implications here, in terms of both the lockout and the globalization of basketball, what is striking is how Williams' decision to sign overseas and the possibilities from other superstars has provoked a backlash from fans and media commentators alike.

Not surprisingly the patriotism and loyalty of players has been questioned, as his been their commitment to the American fans. Similarly, players have been criticized for being greedy, whose sole motivation is to "get paid" (the fact that players were locked out by the owners often gets OBSCURED – ignored – within these discussions). Yet, what has been most striking is the systematic questioning about these players willingness to play overseas. Recycling longstanding arguments about athletes as pampered, over indulged, and spoiled, a charge that has commonplace against black athletes, these commentators both question the willingness of these players to play in non-NBA conditions all while questioning their mental toughness.

For example, Berry Tramel, in "NBA players' threat to go overseas is weak," seems to question the seriousness of threat, asking if, "The players want us to believe they'll sign on to play in venues and under conditions wholly inferior to the NBA standard? In case no one has noticed, the NBA is lavish living. First-class travel. First-class accommodations. First-class officiating. First-class training staffs." Similarly, David Whitley, with "NBA stars would get rude awakening playing overseas" further emphasizes how the NBA lifestyle that players are accustomed to, would not be available to them in Europe or China. "It would also give players a taste of how 90 percent of the hoop world lives. It isn't finger-lickin' good. There aren't a lot of charter flights, much less extra-wide leather seats or five-star meals." In "NBA lockout causing European exodus?"

Umar Ali, while acknowledging the possibility of NBA players going overseas, focused on the horrid conditions there and the spoiled nature of the players themselves.

Though the accommodations pale in comparison to what the average player receives while playing in the NBA - five-star hotel rooms, luxury vehicle transports and catered food compared to second rate rooms on the road, cramped buses and whatever is provided for sustenance - there is still enough to sway players to consider making the transition.

Ali seems to be alone with the majority of the commentaries depicting today's players as high maintenance divas who would not accept the conditions overseas. Skip Bayless, on "First and Ten," scoffed at the prospect of the NBA stars playing in China or Europe longer than a week "because they will not like it. They will not like the conditions; they will not like the travel; they will not like the food, the TV they aren't able to watch." His "debate" adversary, Dan Graziano, not surprisingly agreed, adding "The lifestyle these guys lead over here . . . if they think that will follow them to Europe or Asia . . . it will be a very short period of time before they realize they were mistaken."

At one level, these comments are laughable given globalization. Sports Center is available via Satellite in many counties as is much of American entertainment television. Similarly, American food and products familiar to Americans are commonplace throughout the world. Be real, this ain't Survivor. There also a certain irony in the claims that these players couldn't survive overseas given the long tradition of black artists fleeing to Europe in search of a more welcoming audience and broader community.

Yet, the argument also takes on a more elitist, class-based and nationalist tone, given the stated argument that the rest of the word cannot offer the luxury found in the United States. They might not know about the 5-star hotels found in China, Turkey, and countless other potential destinations. In fact, there are millionaires throughout the world (there may even be Americans living elsewhere – shocking, I know) who live the lifestyles of the rich and famous.

What is striking here is how white racial framing and myopic American nationalism wrapped in exceptionalism guides the conversation. It reflects the longstanding idea that civilization begins and ends at the American shore not only erasing globalization but also the beauty and richness of cultures and nations throughout the globe.

Yet, these comments are just about a myopic and xenophobic understanding of the rest of the world. It is equally a statement about the black athlete. The NBA's primarily black players are reduced to overindulged and pampered babies incapable of working and living in a different location. The assumed luxuries and privileges are constructed as commonplace and expected by the NBA baller, thereby reducing the modern black athlete to being both-of-touch and exceptionally spoiled. It is indicative of a narrative frame that constructs contemporary black-athletes as spoiled brats. In other words, the criticism aren't simply that today's NBA players require a millionaire lifestyle, but worse that these players both expect and demand a lifestyle that they are not grateful for having as a result of their basketball careers.

Writing about the 1995 labor stoppage in Basketball Jones , Kenneth Shropshire described "the dominant public reaction" in distinctly racialized terms. In his estimation, public scorn for the players reflected a belief that they "should be grateful for what you have" (2000, p. 83). "America loves their Black entertainers when they behave properly and stay in their place," writes Todd Boyd in the same collection. "When the players realize their value, their significance to the game, and try to capitalize on this, they are held in the highest contempt" (2000, p. 65).

William Rhoden, in Forty Million Dollar Slaves , further articulates the racial nature of this narrative: "This is a crucial problem with black athletes, the notion that they should be grateful for the things that they've rightfully earned, that they should come hat-in-hand in gratitude for the money and power that they themselves generate. It's this sense of gratitude and subservience . . ." (2006, p. 189). What becomes evident here is that the increased leverage from the players, in their ability to convert their talents and popularity outside the United States into economic gains is becoming the basis for the commonplace narrative that paints the NBA's primarily black players as greedy, ungrateful, pampered, spoiled, and incapable of existing without America.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on July 20, 2011 13:13

July 19, 2011

ReelBlack Talks with Michael Rappaport About 'Beats Rhymes & Life'

ReelBlack had the opportunity to spend a few moments with actor/filmmaker MICHAEL RAPAPORT, whose directorial debut, BEATS RHYMES AND LIFE: THE TRAVELS OF A TRIBE CALLED QUEST was release in the US July 2011.

Published on July 19, 2011 06:52

Death Isn't a Slave's Freedom: The Historic Erasure of Curt Flood's Life

Death Isn't a Slave's Freedom: The Historic Erasure of Curt Flood's Life

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackMan

Death Isn't a Slave's Freedom: The Historic Erasure of Curt Flood's Life

by David J. Leonard | special to NewBlackManNikki Giovanni once write that "death is a slave's freedom" aptly surmising elements of Curt Flood's life and his struggle against America's (white) baseball establishment. Denounced for his efforts to challenge baseball's slave-like conditions and crucified for his efforts to connect baseball to slavery, to American racism, Flood experienced neither vindication nor compensation in part until his death, at which time Flood tasted freedom in a certain way – freedom from the death threats, abuse, ridicule, and American racism.

Yet after watching HBO's recent documentary The Curious Case of Curt Flood, I am less sure that "death is a slave's freedom" in that Flood was unable to escape demonization and ridicule, as the film turned his life into a spectacle of sorts. In an effort to illustrate how the human cost faced by Flood and his family, to highlight the difficult path to redemption, the film spends an overwhelming amount of time on Flood's personal tragedy. Evidence in the divorce from his initial wife shortly after he fought to live in an Alamo neighborhood and the financial, emotional, and physical impact on Flood during and after his suit against Major League Baseball, Curt Flood's life is a testament to the costs of resistance and struggle.

The courageous athlete who dared to challenge an unfair system is depicted as an alcoholic, a womanizer, a woeful husband, a dreadful father, a lousy businessman and a fraud who never really painted those portraits he churned out that enhanced his image as an artist . . . .In the history of warts-and-all biographies, this one slithers near the top of the list.

Curt Flood was a freedom fighter. That didn't begin with his challenge to Major League's Baseball Reserve clause or his rhetorical links to a larger history of slavery. Curt Flood had a long history of fighting for justice. At one level, the film successfully documents how Flood's challenge was not simply about economics but humanity and civil rights. In 1964, when he sought to move his family to Alamo (CA), only to face an owner (and his gun-toting enforcers) that refused to rent to them, Flood took the matter to court. Questioning why they called the street they lived on La Serena (serenity), Flood noted that there was nothing peaceful for a black family because of "fear of some maniac with a gun will sneak up on your kids." The Floods received a death threat and had been called the N-Word shortly after to moving into his dream home. The beauty of the American Dream was unattainable for Flood confirming that his economic success did not affirm his humanity or freedom.

This act of resistance, alongside of his involvement with the civil rights movement, his family history of challenging white supremacy (his mother had to flea the South after she defended herself against a white woman), his challenges to racial discrimination in the allocation of player raises or his involvement with the player's demand that owners disentangle pension contributions from television and radio money, illustrate a larger body of work for Flood. Flood described his political orientation in the following way:

I'm a child of the sixties, I'm a man of the sixties. During that period of time this country was coming apart at the seams. We were in Southeast Asia. Good men were dying for America and the Constitution. In the southern part of the United States we were marching for civil rights and Dr. King had been assassinated, and we lost the Kennedys. And to think that merely because I was a professional baseball player, I could ignore what was going on outside the walls of Busch Stadium was truly hypocrisy and now I found that of all those rights that these great Americans were dying for, I didn't have in my own profession.

The linkages to the 1960s, to a larger struggle for human rights, are evident in Flood's effort to connect baseball to a history of slavery. He was not alone in comparing the exploitation and experiences of black athletes to those of African Slaves of the eighteen and nineteenth centuries. Harry Edwards, Tommie Smith, Muhammad Ali, among others, all sought to contextualize the exploitation and abuse experienced by black athletes within a larger history of white supremacy. He was thus a product of a larger struggle for black humanity and therefore he embraced the language of that movement. In failing to offer this context, we get a curious interpretation of history that individualizes and dehistorizes the struggle for black freedom.

Moreover, Flood's efforts to challenge baseball make sense given his efforts to secure equity and freedom for all Americans. His determination to transform baseball (and America as a whole) was clearly a manifestation of a lifetime of experienced indignities, from the refusal of a locker-room attendant to clean his uniform along with the white players to his movement from the team hotel to the "colored section." The courageous stance that Flood took was thus understandable given his commitment to social justice and the stated impact that a history living inside of American Apartheid had on him. While acknowledging some of this history, the film's focus on the peculiarity leaves viewers with the impression that Flood was "odd" and "different" (which had "positive" and "negative" consequences) rather than a product of a system of class and racial exploitation.

The critiques here are snot imply about the lack of "positive" representations in the film, the erasure of the racism that resulted from his refusal to play by THEIR rules, or even simply about historic accuracy, but rather that the choice to focus on the tragedy and redemption erases not only the contributions of Flood but the ways in which his story provides a historic marker for the larger history about the struggle for racial justice.

In "'Death Is a Slave's Freedom:"' Curt Flood and the Fight against Baseball, History, and White Supremacy" ( Reconstructing Fame: Race, Sport, and the Redemption of Once-Tainted Reputation s, eds., David C. Ogden & Joel Nathan Rosen – University of Mississippi press), 2008) I explore the ways in post-death media commentaries and political posturing celebrated Curt Flood (as part of efforts to demonize contemporary black athletes and celebrate American racial progress), his contributions to baseball, and his courageous stance against Major League Baseball. In this article, I wrote the following:

Be sure, the story of Curt Flood is certainly one of courage and resistance, but it is equally a story of power, of the powerful and the great lengths the powerful have gone to maintain that control, those privileges and traditions that guaranteed their hegemony. In the end, however, only death could save him from the demonization, from the alcohol and drugs that invariably served as an antiseptic for the pain and poverty, from the letters and stares, from the exile, banishment and denunciations. This part of the story found little place in the reclamation projects that dominated the landscape following his death, but they certainly bear our attention in a time of increasingly reactive and certainly even reactionary narrative.

Even the respect that his legacy has garnered in the days and years after his death (although despite his contributions on and off the field Flood unjustly remains outside of the Baseball Hall of Fame) has not resulted in a full appreciation of the life, courage, and humanity of Flood. It results neither in Flood's freedom nor for the freedom that he fought to secure during much of his life. Meager honors given in death do little to alter the persistence of racism and injustice inside and outside of sports. Lip service in the afterlife will not suffice nor will memory, especially when historic memory is confined by stories of personal tragedy and redemption; such memorials are unable to secure justice for Curt Flood, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Ella Baker, Dorothy Dandridge, or any of the nameless people history selectively remembers. Death will be the only potential avenue for freedom should the injustices done to Flood, and myriad forgotten others, continues. And even that will remain illusive because for Curt Flood death isn't freedom because if it were we would be talking about courageous activism in the face of racism and the hall of fame not that other stuff.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on July 19, 2011 06:37

July 18, 2011

Preview: The Captains--Kirk Meets Sisko

The Captains - an Epix Original Documentary produced and directed by William Shatner. In The Captains, he travels the world to connect with each of the actors who have played Captains over the long life of the Star Trek franchise. Shatner recalls his own experiences in the role that made him a star by interviewing Patrick Stewart, Kate Mulgrew, Scott Bakula, Avery Brooks and Chris Pine while interweaving clips from their respective shows and movies.

Debuts on EPIX, July 22, 2011

Published on July 18, 2011 18:18

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.