Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 177

September 30, 2013

Guest blogging at Best American Poetry

I'm delighted to be able to say that I'm guest blogging at The Best American Poetry blog again this week. I won't be posting poetry there -- their guest-blogger guidelines haven't allowed that in some years, though the ones I posted long before that guideline was in place (from Sestina featuring six words commonly used on this blog to Preparing to Leave Jerusalem to Progression) are still in their archives -- but I'll be offering short reflections on life, poetry, spirituality, parenthood, music, and remix culture over the course of the week.

If you're so inclined, please do click over and read my posts there -- and consider following the BAP blog and/or @BestAmPo twitter stream, both of which are terrific.

Here's how this week's first post there begins:

Every year I'm surprised by how variable the change is. The other night,

when it was still Sukkot, we had a pair of friends over, a couple we've

known since college and their son. Our son, who is almost four, proudly

explained that this -- gesturing to the little skeleton of a house,

garlanded with tinsel -- was a sukkah and that his dad had built it and

we had decorated it. Then he explained that the leaves on the trees

around us are turning orange and yellow because it's fall. The two

statements seemed of equal import, coming out of his mouth...

Read the whole thing: The Change [by Rachel Barenblat] at The Best American Poetry blog. My thanks go to the BAP blog editors for inviting me to blog there this week!

September 29, 2013

Seasonal

A kind of emptiness comes at the end of this long cycle of holidays. After challah and honey, feasting and fasting, services upon services upon services. Just listing the names of all of the observances of the last few weeks tires me out again.

A kind of emptiness comes at the end of this long cycle of holidays. After challah and honey, feasting and fasting, services upon services upon services. Just listing the names of all of the observances of the last few weeks tires me out again.

Sometimes memory telescopes in a way that makes far things seem near. At this moment in the year, though, I tend to find that it works the other way around. Things which happened not so long ago feel like ancient history. That first dinner, on the cusp of Rosh Hashanah...? It was another eon.

In a way, in Jewish time, it was another eon. That dinner was before we ushered in the new year. That was 5773, relegated to memory now. I like the fact that I spent my last hours of the old Jewish year sitting around a table with my family, eating and talking and being together.

I went for a walk few days ago. I didn't have the energy to contemplate driving someplace particularly beautiful or noteworthy, so I walked up and down our driveway a few times. It's a long driveway, and parts of it are steep. I paused from time to time to take photographs, working at reminding myself that even mundane places are worthy of attention.

I don't know what these seed pods are, but I find them strangely beautiful. I feel a little bit like these pods right now: burst open, after the pressures of all of these rituals and services and prayers. The silky stuff of my heart exposed under the early autumn sky.

What always amazes me as we move into fall is how slowly it unfolds. Even a single tree can seem to be straddling two seasons, summer and fall, at the same time. Maple trees which are mostly green save for one brilliantly red branch. Or this beech tree with a river of yellow leaves running through it.

What always amazes me as we move into fall is how slowly it unfolds. Even a single tree can seem to be straddling two seasons, summer and fall, at the same time. Maple trees which are mostly green save for one brilliantly red branch. Or this beech tree with a river of yellow leaves running through it.

Are the trees holding on to the now, or are they sliding gracefully into the future? Am I?

I dug up Mary Oliver's poem "5am in the pine woods" because I wanted to see again how she reaches its closing lines, which I love so much:

so this is how you swim inward,

so this is how you flow outwards,

so this is how you pray.

I first encountered those lines thanks to Rabbi Eliot Ginsburg, at the end of my first Jewish Renewal Yom Kippur retreat at the old Elat Chayyim. He was talking about the rhythm of moving from the Days of Awe to Sukkot. The Days of Awe are focused on all of that teshuvah and internal work. And then we shift again, from inward to outward.

Sukkot is "outward" in several senses: the Sukkot sacrifices in antiquity were on behalf of the entire world, not just our own nation -- and of course during Sukkot we literally move outward, moving out of our homes and into those fragile little structures for a week.

But after Sukkot, then what?

Jack Kornfield reminds us that "after the ecstasy, the laundry." Whether or not we found ecstasy during the Days of Awe (whether or not ecstasy was even what we were seeking), how do we navigate the transition from this intensive and overwhelming season to ordinary life again? What comes next?

Jack Kornfield reminds us that "after the ecstasy, the laundry." Whether or not we found ecstasy during the Days of Awe (whether or not ecstasy was even what we were seeking), how do we navigate the transition from this intensive and overwhelming season to ordinary life again? What comes next?

On the Jewish calendar, what's next is a whole lot of nothing. Next Friday when we reach new moon we'll enter into the month of Cheshvan, renowned because it has absolutely zero holidays. None. Zip. Nada. Nihil. Nadie. It is the only month which bears this particular distinction.

Our sages named this month MarCheshvan, "bitter Cheshvan," because of this lack of official simcha. Most of the rabbis I know relish Cheshvan for the exact same reason seen through a different lens: it's a chance to pause, to take a breather. After the marathon, a pause.

An opportunity, maybe, to take more walks up the driveway and notice the little changes which are unfolding in the world around me as one season gives way to the next. As I write these words, Cheshvan is almost within reach. A time to start practicing what it means to lie fallow.

A time to let the experiences of these awesome days burrow deep into the soil of my heart and soul, and to trust that when it's time for new insights to emerge, I'll be ready to receive them. Maybe in the spring.

September 26, 2013

Remembering our beloveds as we linger a little longer

Shemini Atzeret: "the pause of the 8th day." The day after Sukkot, when the Holy Blessed One murmurs in our ear, "Don't go just yet. Don't leave this bower where we've spent this past week. Linger a little longer with Me."

Shemini Atzeret: "the pause of the 8th day." The day after Sukkot, when the Holy Blessed One murmurs in our ear, "Don't go just yet. Don't leave this bower where we've spent this past week. Linger a little longer with Me."

Shemini Atzeret: the day when we shift, in our daily amidah, from blessing God Who brings the dew to blessing God Who brings the wind and the rain. (And in this climate zone, eventually, the ice and the snow.) On this day we recite a special prayer for rain.

Shemini Atzeret: another opportunity to say the prayers of Yizkor, the liturgy of remembrance which recite as we remember our beloved dead. Of course, many of us just said Yizkor. There was a Yizkor service on Yom Kippur, a scant twelve days ago. Why are we reciting Yizkor again so soon?

Well. Like anything else in Judaism, there is a multiplicity of answers. But here's an answer which speaks to me.

We say the prayers of

Yizkor four times a year. I follow the tradition which maps these four

Yizkor services to the four seasons: Pesach – springtime. Shavuot –

summertime. Autumn – Yom Kippur. Winter – Shemini Atzeret. Granted, Shemini Atzeret

isn’t during the wintertime (especially not this year.) But some sources suggest that the

fourth instance of Yizkor was originally meant to happen at midwinter. Because arduous winter

travel could keep people from making it to Jerusalem to gather for this remembrance, the sages of our tradition moved the wintertime

Yizkor to this "extra day" at the end of Sukkot. It's a kind of vestigial winter observance, almost hidden amidst Sukkot's palm fronds and hospitality.

Each of the four Yizkor services during the year has a different valance, a different feeling-tone. During the springtime Pesach Yizkor, I feel most connected with my grandparents. My grandmother Alice, aleha l'shalom, died shortly before Pesach one year, and her loss was immediate and palpable. My experience of Pesach is always intertwined with the memory of her death.

The Shavuot Yizkor comes at the start of summer, as we're moving into the season of real warmth and fruitfulness where I live. Shavuot is a time of bringing first fruits before God. Maybe that's why the Shavuot Yizkor feels to me like a time to bring the metaphysical harvest of my winter and spring before my beloveds who are gone.

During the Yom Kippur Yizkor service, everything feels heightened: the skies a bit too bright, my heart a bit too raw. Fasting and praying all day (and doing so on my feet all day!) can take me into a kind of altered state. Often the veil between my life and their memories seems most transparent on that day when, tradition teaches, our world is closest to God's perfection.

And then there's today's Yizkor. Of today's Yizkor, Rabbi Arthur Waskow writes, "On Sh'mini Atzeret we remember the dead in yizkor and then pray for

water. Is our water prayer a plea for drops of rain alone — or also for

tears, the ability to cry? Tears less exalted than those of Yom Kippur,

less frightened than those of Tisha B'Av — but tears of memory and

compassion?"

In the image I chose to accompany this post, hands are cupped around a memorial candle, cradling its flame. Sometimes that's how Yizkor feels to me: as though we are cupping our hands around the flame of memory, protecting it from the winds which might blow the candle out. In my hemisphere the days are growing shorter. It seems a fitting time to go inward, to find a still point in my own heart, and from that place of stillness to call out to those I have known and loved who are gone.

In "A Meditation / Kavanah for Yizkor," Reb Simcha Raphael writes:

Jewish tradition, in its wisdom, teaches us that between the world of the living and the world of the dead is a window and not a wall. Raised in a culture of scientific materialism, many of us have been led to believe that dead is dead, and after death, the channels of communication between us and our loved ones who have died are forever ended - a brick wall! But, like the rituals of Shiva, Kaddish, and Yahrzeit, Yizkor opens windows to the unseen worlds of the dead. Yizkor creates a sacred space and time wherein we can open our hearts and minds to the possibility of a genuine inter-connection with beloved family members and friends who have left behind the world of the living. Yizkor is a window. Prepare to open that window.

(That prayer can be found in this list of OHALAH resources for Yizkor.) My teacher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi speaks of Yizkor as a "holy

Skype call" — an opportunity to go inside, perhaps draped beneath one's

tallit, and call up the memory of the person we have lost, and imagine

them before us face-to-face, and say whatever it is that we most need to

say to that person right here, right now.

As the winds whip the schach from the roofs of our sukkot, as we prepare to batten down the emotional and spiritual hatches for winter's approach, what do you need to say to your loved ones who have left this life? What would it feel like to believe that in some inchoate way, they are really here; they can really hear you?

September 25, 2013

Decoration

The rainbow foil garlands broke

on the night of heavy rain.

Slivers of color adorn the lawn.

Your tears fell like willow leaves.

You insisted we find

the decoration store.

This slow disintegration

is part of the point, each sukkah

as fragile as a life, but

who understands that at four?

A compromise: the art supply box,

our spool of kitchen string.

Now paper plates spin and clatter.

Their crayoned markings face me

then whirl away

like your laughing face

hiding under our blanket

then bursting back into view.

Re: "Your tears fell like leaves" -- today is Hoshanna Rabbah, when it is customary to beat our willow branches on the earth; their falling leaves represent our prayers for rain.

(Photo source: flickr.)

September 24, 2013

Operating Instructions (a poem sparked by Pirkei Avot)

Judah the son of Tema would say: Be bold as a leopard, light as an eagle, fleeting as a deer and mighty as a lion to do the will of your Father in heaven. -- Pirkei Avot 5:20

Be bold as brass,

polished until you gleam.

Be fearless and daring; courageous.

Be distinct to the eye.

Be imprudent. Be bold as love.

Be light as a pinfeather.

Swift as a cheetah running

at full tilt, fleeting

as an eager football player's

triumphant return to the field.

Be as mighty

as an unexpected synonym,

as the thirteen-petaled rose,

as the Niagara Falls of justice

thundering endlessly from Eden.

Everyone serves something. Choose

hope's pulse and flicker,

creation's compassionate heart.

The quote which sparked this poem is emblazoned on one of the sukkah decorations which came in the sukkah-decorating kit I ordered online. I love the Biblical similes.

September 23, 2013

A glimpse of Jay Michaelson's Evolving Dharma

"The Western world is on the cusp of a major transformation around how we understand the mind, the brain, and what to do about them. Meditation and other forms of contemplative practice, once the provenance of religion, then later of 'spirituality,' are now in the American mainstream, in corporate retreats and public schools, as a rational, proven technology to upgrade the mind and organize the brain, buttressed by hard scientific data and the reports of millions of practitioners."

That's the opening of Evolving Dharma: Meditation, Buddhism, and the Next Generation of Enlightenment, by Jay Michaelson, due out in October 2013 from North Atlantic Books. Jay writes:

"The original source of these cognitive technologies is the dharma, an ancient word meaning the way, the path, or the teaching. In the most general sense, it can simply refer to the truth of how things are: the laws of the universe, and of the mind...

What was once a monastic tradition of meditation, virtuous action, and wisdom teachings (samadhi, sila, and panna) is now, depending on where you encounter it, a technology of brainhacking; a way to build insular thickness in the brain; a way to lower stress; a mystical path filled with unusual peak experiences; a way to grow more loving, compassionate, and generous; a method to get ahead and gain an edge on your competition; or any number of other things. Love it or hate it, the dharma has evolved."

This new book aims to explore the evolution of the dharma through a variety of lenses. There's history here; there's neuroscience; there's personal experience. There's also a straightforward narrative voice which is unsentimental and occasionally quite wry.

This is a story of monks and soldiers; a history as well as a tale told from my own cultural position, conditioned by my age, gender, class, race, sexual orientation, and all the rest; a narrative of maverick teachers, online communities, Occupy, self-loathing, stress reduction, religion, sex, power, and Google.

Who wouldn't want to read that?

Full disclosure: I've been blessed to work with Jay off and on for a number of years. He is the founding editor of Zeek, "a Jewish journal of thought and culture," where I used to serve as a contributing editor. I come to this book as a colleague of the author's, as a rabbi, and as someone whose own spiritual life has been strongly shaped both by Judaism and by the import of Buddhism to these shores. Those are some of the lenses I bring to bear on reading this book.

Early in the book, Jay tells the story of hiking in Wadi Rum and seeing a mountain which, through a trick of perspective, seemed to be perched right on the horizon. He set off toward that mountain. Of course, by the time he drew near, he could see that it was not at the edge of the world, but that beyond it lay more mountains. "What I thought was the end of the path was, in fact, more of the path. The scenery had changed. But after a couple of hours of desert hiking, my perspective had changed also." It is a perfect lived metaphor for spiritual life.

Meditation and mindfulness are, Jay notes, practices -- meant not merely to be read about, but to be done, and done again. There are, of course, pitfalls not only in the practices themselves but in the impulse to write about them and make meaning out of them. Here's a bit which particularly resonates for me:

I have an experience in 2013, I read a text written in 1648, and since the two descriptions appear to correlate, I take an ahistorical leap and say we're talking about the same thing. It's a problem. But the alternative is mere description; spiritual journalism, really, which I find uninteresting and so should you. I want to talk not just about sociological trends or phenomenological characteristics of the contemplative path, but about technologies that transform lives -- including my own.

I can relate: to the experience of correlating my own spiritual experience with texts written in another century, often another paradigm -- and to the recognition that equating my experience with that older experience is a kind of dangerous erasure of difference -- and to the inclination to make the leap anyway, because what interests me most is how spiritual practice can transform and enliven us and our world.

Our lives, Jay notes, are inevitably imperfect and impermanent -- not only on the grand scale, but in countless small ways, too:

On the grand scale, we will all die, and lose much of what we love along the way. Yet even in our mundane lives, we lose the battle every day -- often in ways less tragic than comic: the damn webpage won't load, the mortgage has to be paid, the boss is a jerk, I'm a jerk -- every day, the God-or-evolution-given instinct to "want it all" butts up against a reality that rarely provides it... This is the core of the dharma: the completely natural state of affairs is one in which human beings cause suffering for themselves and others.

Fortunately, the instincts to fight, flee, and have sex are not the only faculties in the mind. And so, for thousands of years, people in various religious, philosophical, artistic and other traditions have cultivated other qualities, among them capacities for wisdom, empathy, letting go, relaxation, concentration, compassion, awareness -- not to mention justice, gratitude, love, and a sense of wonder.

Amen to that. Reading that list of qualities, I'm reminded of the strings of praise so endemic to Jewish liturgy -- we laud, thank, praise, glorify, etc, etc. It can be easy for such a list of qualities to become rote. But when you stop and take each quality seriously, there's something pretty remarkable about our human striving to turn away from our worst selves and to cultivate our best selves. At its best, I think, that's a big piece of what spiritual practice can help us to do.

Jay describes the Buddha's view as almost mechanistic: "water the garden of greed, and you get greedier; nourish the saplings of compassion, and eventually they grow instead." This is, he argues, not magic but something akin to installing a new operating system on the hard drive of the brain. It's exercise. Enter into new practices (contemplation, compassion) -- stick with them until they become habits, become second-nature -- and we can change how our brains work.

He acknowledges that in Theravadan Buddhism, the aim is not merely to build mental muscles but to exercise them in a particular way -- to cultivate understanding that transitory phenomena are impermanent, not ultimately satisfactory, and interdependent with everything else. (This is fine stuff to be reading during Sukkot.) But in the last quarter century the dharma has evolved by moving out of its original religious context; now it appears in any number of forms, ranging from secular settings to other religious contexts altogether. (There's a lot of mindfulness and complative practice woven into Jewish Renewal, e.g. -- if that's your cup of tea, don't miss Rabbi Jeff Roth's Awakened Heart Project.)

There's some good history here of the migration of Buddhism to American shores -- the transcendentalists taking an interest in the nineteenth century, D.T. Suzuki's foundational work in bringing Zen to American audiences, Alan Watts and Allen Ginsburg, eventually Ram Dass (about whom I wrote several years ago), Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Thich Nhat Hanh. Many of us who pick up this book will probably have had experiences with at least some of these teachers and thinkers -- if not in person, then through their writings and the impact of those writings on our lives. (I still own my marked-up college copy of Thich Nhat Hanh's The Heart of Understanding, his commentaries on the Prajnaparamita sutra. "If you are a poet you will see clearly that there is a cloud in this piece of paper..." -- it was radical to me when I was eighteen, and still moves me deeply at thirty-eight.)

Jay writes about the "new, Western dharma" which began to take shape -- marked, says Lama Surya Das, by "a dharma without dogma, a lay-oriented sangha, egalitarianism (particularly with regard to gender), and an engaged, simplified, pragmatic, and experimental orientation." One of the things I appreciate most in this section of the book is Jay's persuasive case that change has always been a part of these paths -- that evolution was already a part of the dharma well before it came to the West.

Naturally, there are Buddhist purists who object to the extraction of Buddhist meditation from Buddhist belief, ritual, and form. There are scholars of Buddhism dismayed at the selective and ahistorical ways in which "convert" Buddhists relate to Asian Buddhist traditions. And...there is a new generation of neo-Buddhists who are returning to precisely the forms and contexts set aside by Kabat-Zinn, Siegel, and company, refocusing on liberation as the goal, and appreciating how the traditional contexts support intensive practice.

The movement which Jay describes there -- an old and 'Orthodox' tradition, a movement toward new rituals and forms which causes some dismay on the part of the traditionalists, and eventually a new generation of neo-practitioners who are returning to the old forms and appreciating how those forms can support modern practice in their new paradigm -- is entirely familiar to me.

Contemplative practices, Jay acknowledges, are not necessarily fun:

Sitting for endless Zen sesshins or performing thousands of prostrations to Padmasambhava -- no, dharma practice is not a day at the beach, or the spa. It's the opposite, really. If a vacation banishes all cares from the mind, a meditation retreat puts them right smack back in front of you...

[That said,] there's no denying that mindfulness does work in these various new, quasi-therapeutic contexts -- that's why it's spreading, of course. And there's nothing wrong with teaching people to relax -- wasn't the Buddha interested in reducing suffering? Well, stress is suffering and relaxation is its release. So I think Orthodox Buddhists need to, well, relax.

...We hardcore dharma practitioners need to make peace with Western mindfulness practices. They are indeed adaptations of the dharma, and not the dharma itself -- but the dharma is evolving into new forms and contexts quite remote from their Buddhist origins.

Some of the material in this book has been published in other forms, though it's been polished and recontextualized in its new setting. For instance, I remember reading Jay's multi-part essay A Jewish perspective on the jhanas in Zeek years ago. But even the material I'd seen before takes on new resonance in this new context.

There are a number of places where I have scribbled marginalia -- lines, double lines, exclamation points. Here's one of them:

Letting go is not the same as not having in the first place. If you choose to pursue a career that involves arguing with people about politics, conflict is going to arise, and the mind is going to react. That is just inevitable. But what is not inevitable is how those reactions affect you: how coolly or heatedly you reply...Similarly, if you have a family, particularly one with children, you are going to go on an emotional roller-coaster ride; that is the nature of raising a family. But what is up to you is how the roller-coaster feels: the ratio of anxiety to glee, fear to release.

That second example -- the family one -- is the one which made me draw marks of recognition in the margins. Just ask me what goes through my mind in the morning when our almost-four-year-old refuses to put on daytime clothes so we can get out the door to work and to preschool! But what Jay says here is right on: the roller-coaster is a part of every day. What's up to me is how the roller-coaster feels, and how I choose to respond to my kid when he's pushing every one of my buttons. Or, as Jay writes a bit later, "'What's wrong?' you might ask, 'I'm doing all this work, but I still get pissed off at my mom!' Well, sure, welcome to being human." Cue the rueful laughter of readerly recognition.

Jay offers a terrific metaphor for the mix-and-match quality of spiritual life for many people today. Remember when one used to acquire music by going to a store and purchasing a physical artifact, a record, created and curated by experts, which each of us might consume? Today, in contrast, we're accustomed to a world in which participants (not passive consumers) buy, stream, download, and/or trade music. We create our own playlists, often privileging diversity over stylistic uniformity. We assume that when it comes to music, each of us is capable of co-creating her/his own experience. The same is true today, Jay argues, when it comes to spirituality. He writes:

All identity, but in particular "spiritual" or "religious" identity, is similar. The dharma is evolving in a multi-identity world -- we live in the age of iSpirituality, no less than the age of the iPod. As with music, everything is now available all of the time. Participants (formerly parishioners, consumers, or target markets) expect, not as a matter of au courant hipdom but simply as a matter of course, that they will have a role in constructing their identities and experiences -- and that they will do so from a variety of different sources, in their own distinctive ways. Top-down curation, unformity of program offerings, and mono-identity are as outdated as those old 33s.

In today's paradigm we presume that we are co-creators, not consumers -- and we assume that we will create our identities and roles by drawing on a variety of sources, traditions, aspects of our selves. As a rabbi I know that this impacts how people "do Jewish" in the world today. Of course it also impacts how the dharma is experienced and articulated by its practitioners -- even those who wouldn't necessarily call themselves devotees of the dharma or walking its particularized path.

Later chapters in the book will touch on other facets of the dharma as it evolves. On this reading I'm particularly struck by some of the material on the intersection of Buddhism and queerness. Jay writes, "I'm interested in how queering the sangha problematizes the ways in which patriarchy is perpetuated...and how Buddhist notions of non-self call all of us who work in 'identity politics' to question how we may be reinscribing oppression by defining our identities in response to it." My own relationship to identity politics is a complicated one, in part because of this very tension which Jay articulates here. I'm glad to see his exploration of this stuff.

Jay also offers valuable perspective on the intersections of contemplative practice and justice. Once contemplatice practice has opened one's eyes to injustice and one's role in causing or perpetuating injustice, that same contemplative practice demands that one stop causing or perpetuating the injustice. Or, in Jay's more elegant words, "You can't see clearly, cause suffering, and be okay about it." Later in that same chapter, he observes, "There is, seemingly inherent in political life but amplified by our current social and technoogical structures, a tendency to praise anger, to defend 'righteous indignation,' and to reward brashness and zeal." I've noticed that too, and it challenges me. A lot. But, Jay argues, if we can be more conscious of the movements of our own minds, we can steer our own impulses toward generosity. "These small movements of the mind are, to me, the reasons contemplative practice might really save the world." What we need, he says, is "to install better cognitive software in people of all political persuasions."

For me as a reader, the most powerful moments in the collection are the small ones where Jay speaks about his own spiritual practice and how it's changed him. He writes that his spiritual life really "took off" when he stopped looking for a guru -- and recognized that his spiritual life was inevitably going to be as multifaceted as he himself is. "I realized that there was not going to be anyone who would 'get' all of me: the Jewish, the Buddhist, the queer, the earth-based, the plugged-in, the geeky, the freaky, the square, and the shy," Jay writes. Reading that line, some part of me wants to wave my hand in the air and shout "me too!" (Granted, my matrix of qualities isn't exactly the same as Jay's -- but it's not dissimilar, either.)

Near the end of the book, Jay quotes Lama Surya Das, then continuing in his own words:

'We have to occupy the dharma, occupy the spirit, not just leave it for the one percent, the Dalai Lamas and Thich Nhat Hanhs. Ocupy the dharma -- that's the Buddha's intention.' The dharma is not unattainable, not just for saints and mystics -- you can do it.

Or, in the words of the Jewish tradition which Jay and I share, "This mitzvah that I am prescribing to you today is not too wondrous for you, it is not too distant. It is not in the heavens that you should say 'Who shall go up to Heaven and bring it to us so that we can hear it and keep it?' It is not over the sea so that you should say 'Who will cross the sea and get it for us, so that we will be able to hear it and keep it?' It is something that is very close to you. It is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you may do it." (Deuteronomy 31:11-14) Here's hoping that it really is that reachable -- and that we'll reach out and take hold.

Every life is a sukkah

Our sages have asked: what is a sukkah?

Some have said: it’s a remembrance of the tents we lived in during the exodus from Egypt. As we read in Torah, "You shall dwell in sukkot seven days, that your generations may know that the children of Israel dwelled in sukkot when I brought them out of the land of Egypt." When we sit in the sukkah, we remember the Exodus.

Others have said: it’s a reminder of the cloud of glory which traveled with us during the exodus from Egypt, the pillar of cloud by day and pillar of fire by night. When we sit in the sukkah, we experience God's presence and God's glory.

Still others said: it’s a harvest house, a reminder of the temporary dwellings our ancestors used to build in their fields during harvest time. When we sit in the sukkah, we remember our agricultural roots, and feel gratitude for the harvest.

And still others have said: a sukkah is temporary, beautiful, vulnerable, a place for welcoming guests and connecting with people (both those who are in our lives, and those ancestors whom we remember with love) — it is an embodied metaphor for a human life.

Like a sukkah, each life is temporary. Each life is beautiful. Each life is vulnerable. Each life is enriched by the presence of our loved ones, both living and imagined. Into every life a little rain must fall, but when we sit in the sukkah, we have the opportunity to greet even that rain with joy.

Adapted from a teaching originally posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

September 22, 2013

Cloud of glory: a d'var Torah for chol ha-moed Sukkot

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday morning at my shul. (Crossposted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

This Shabbat falls during chol ha-moed, the intermediate days in the midst of the festival of Sukkot. The appointed reading for today (Exodus 33:12–34:26) does make brief mention of Sukkot. Almost at the very end of the parsha we read "And you shall observe the feast of weeks, of the first-fruits of wheat harvest, and the feast of ingathering at the turn of the year." The feast of weeks is Shavuot; the feast of ingathering is Sukkot.

But mostly this parsha is about something different: a request from Moshe, and God's intriguing answer.

"If I have found grace in Your sight, show me Your ways," asks Moshe. And then Moshe adds, "Show me, please, Your glory."

In response, God says: "I will make My goodness pass before you, and will proclaim My name before you, and I will manifest graciousness and mercy -- but no one can look upon Me and live."

As some of our b'nei mitzvah students would be quick to remind me, God doesn't "look like" anything -- God doesn't have a body -- so what would it even mean to look upon God?

It seems to me that the Torah here is speaking, as it so often does, in metaphor. First, Moshe asks "show me Your ways," and God is happy to comply; in a sense, the entire Torah is God showing us God's ways. But then Moshe asks to see God's kavod, God's glory. And God says, that's not possible. Here is one reason why that might be.

Much later in our history, the kabbalists would speak of God as ein-sof, "Without End." God is infinite, limitless, vaster than our human minds can comprehend. Any human mind which actually expands far enough to encompass all that God is would...crack open, I think. Would be stretched beyond its limits. God is precisely that infinity which we can't comprehend.

Instead, God gives Moshe a different option: stand in a cleft of rock, and after I pass by, you can see My afterimage. I believe that we can see God's afterimage all over creation: in our relationships, in our ethical obligations to one another, in moments of transcendence and power in our lives. Each of these is a tiny cellular glimpse of a facet of all of what God is, as in a hologram where each part contains the whole.

Later in the parsha, God tells Moshe to make a second set of tablets out of stone. God descends in a cloud of glory, and proclaims God's own Name, as we've been reciting it all through Yom Kippur! ...well, not quite as we've been reciting it. The version in Torah goes like this:

Adonai! Adonai! God, Compassionate and Gracious, Slow to anger and Abundant in Kindness and Truth, Preserver of kindness for thousands of generations, Forgiver of iniquity, willful sin, and error, and Who Cleanses (but does not cleanse completely, recalling the iniquity of parents upon children and grandchildren, to the third and fourth generations.)"

-- whereas the one we know ends with "...and Who Cleanses," leaving out the part about visiting the sins of the parents on the children. Our sages call these the Thirteen Qualities (or Paths) of Mercy, and teach that it is through these thirteen paths of mercy that the world is governed and sustained.

Perhaps this Torah portion suits Sukkot because during this week, as we live (or at least eat, drink, and hang out) in our little temporary houses, we are viscerally reminded that we are dependent on these attributes of mercy.

Here's one more connection between this parsha and Sukkot. This is a teaching from Rabbi Jill Hammer:

The Talmud records an argument between Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Akiva. Rabbi Akiva claims the sukkah represents the real, fragile homes of the Israelites in the wilderness. Rabbi Eliezer, on the other hand, claims that the sukkah represents the clouds of glory, and the hovering protection of the Shekhinah (Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 11b). In fact, the sukkah holds both of these truths: the fragility of physical life and its abundance, the ephemerality of the spirit and its vast strength.

Our sukkot don't just represent the temporary huts our ancestors might once have dwelled in during harvest season -- or the tents our ancestors might have dwelled in during the 40 years of wandering -- but also the clouds of glory and the hovering protecting of the Shekhinah, God's immanent, indwelling Presence caring for us in our lives.

When we sit in our sukkot and allow ourselves to be fully present, we can experience the cloud of glory -- that same kavod, glory, which Moshe asked about but was not able to see. We may not be able to process the infinity of God's glory with our finite human minds, but when we sit in our sukkot this week, we can experience the merciful presence of Shekhinah. Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so!

September 21, 2013

Turn of the season

Maybe today's the day it won't warm up.

Goldenrod burns fall's first fire.

Doorways and front stoops sing

pumpkins and mums, pumpkins and mums.

The woodchuck waddles low across driveway

from grass to grass.

Everything's green, though yellow lurks

beneath the visual spectrum, waiting.

Listen: there's the rise

and fall, rise and fall I wait for,

breath half-held. One of these days

I'll forget there should've been sound.

Three months and the wind will whisk snow

against windowpanes, but today:

breathe warming dirt, the lawn's wild thyme.

The woodchuck munches, focused, getting ready.

This is a revision of a poem which I wrote ten years ago. In 2005 it became part of a manuscript called Manna which I sent around to first-book contests for some years. I had thought that this poem had appeared in The Berkshire Review, but my records show other poems in that journal during that time, not this one. Anyway: I find myself thinking of the "pumpkins and mums" line every year at this season, so I dug up the poem and did a bit of polishing and am sharing it here in honor of the equinox. Hope y'all enjoy.

For those who are so inclined, here's the traditional blessing for the tekufah, the equinox (which comes from Talmud):

Blessing for the Tekufah / Equinox

ברוך אתה ה' אלהינו מלך העולם עושה בראשית

Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam, oseh vereishit.

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Source of all being, who makes creation.

September 20, 2013

Two author events in Montréal next month

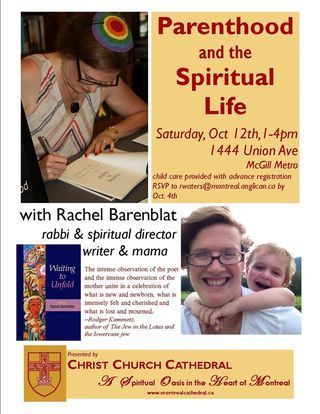

I'm delighted to be able to announce that I'll be returning to Montréal in about three weeks (over the weekend of Canadian Thanksgiving) for a pair of author events.

The first will be on a Saturday afternoon at the Anglican church in Montréal, Christ Church Cathedral:

FAMILY SATURDAY, October 12th, 1-4pm in Fulford Hall (Eng) Join Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, author of Waiting to Unfold (Phoenicia, 2013) a collection of poems which offer an honest look at the challenges and blessings of early parenthood. Discuss the relationship between

parenthood and spiritual life. Childcare will be provided. Register with the Reverend Rhonda Waters as soon as possible.

And the second will be on Sunday morning, October 13th, at the Unitarian Church of Montréal. They'll be having their usual Sunday morning service, which will center that week around themes of gratitude (since it's Canadian Thanksgiving weekend) and on music (they're hosting a choral immersion weekend.) They've graciously asked me to offer the sermon, which will also touch on themes of gratitude -- and will almost certainly involve some poetry, as will the rest of the service.

Copies of both 70 faces (Phoenicia, 2011) and Waiting to Unfold (Phoenicia, 2013) will be available for sale at both events.

Both events are free and open to the public -- these are not for (Episcopalian or Unitarian Universalist) parishioners only, but for anyone of any faith who's interested in the intersections of poetry, scripture, parenthood / life in the world, spiritual life, and cultivating gratitude! If you're in the area, or able to get to the area, I hope you'll join us.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers