Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 173

November 17, 2013

Seeing the wrestle as a blessing: thoughts on Vayishlach

Here's the d'var Torah which I offered yesterday at my shul. Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

At the start of this week's Torah portion, Vayishlach, Jacob prepares to meet his twin brother Esau. This will be their first meeting since Jacob tricked their father into giving him the oldest son's blessing. He rises in the night and sends his family on ahead of him, across the river Jabbok.

Jabbok: יבק. Jacob: יעקב. The two words are made up of the same letters, though Jacob's name has an extra letter, a silent ע. Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh teaches that this letter connotes vision.

"Now Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until the rise of dawn."

Our tradition understands unnamed men in Genesis to be angels, which is to say, divine messengers.

At the end of their wrestling match, Jacob demands a blessing. The blessing he receives is a new name, Israel, "for you have struggled with God and with human beings, and have prevailed."

My teacher and friend Rabbi Arthur Waskow translates Israel as God-wrestler. Israel is the one who wrestles with God. And as we are the people Israel, the community which bears his name, then wrestling with God is our task, too. Perhaps this means wrestling with the texts in Torah which challenge us, or wrestling with ethical questions about what kind of life we intend to lead.

After this encounter, Jacob names the place of the wrestle Peni'el, "the Face of God," saying, "For I have seen God face-to-face, and my life is spared." In the Biblical understanding, no one can look upon God's infinity and live. Jacob has seen only a face of God, a facet of God, a refraction or reflection of God in the person of the angel with whom he wrestled.

"Only" a face of God? How remarkable it would be if we could see the face of God in every being we meet.

Your face: a face of God. Her face: a face of God. His face: a face of God...

After Jacob's wrestle with God in the person of the angel, he meets up with Esau -- with whom he wrestled even in the womb. But perhaps Jacob's God-wrestling has changed him; he doesn't fight with his brother this time. And perhaps Esau has experienced some God-wrestling of his own (though Torah never tells us so) -- because Esau doesn't fight with Jacob, either.

A changed name, in Torah, denotes a changed person. Surely this is the reasoning behind that old folk custom of changing a sick child's name -- to fool the Angel of Death into not taking that child, because a changed name means a changed human being.

But after this name change, our patriarch will be known sometimes by one name, sometimes by the other. He is both Jacob and Israel. And so, I would argue, are we.

Earlier this morning when we sang Mah Tovu, I noted that it refers to Jacob's tents and to Israel's mishkanot, dwelling places for God's presence. Jacob was the worldly guy who lived in a tent; Israel was the God-wrestler whose very tents were transformed into dwelling places for Shekhinah.

Most days we begin in Jacob-consciousness. We wake up already consumed by the newscast, the radio, the details of the morning, putting gas in the car, getting the kids off to school. But it's always possible to rise up into Israel-consciousness, in which each person we meet is a facet of God.

Jacob's name change happens on the banks of a river which more-or-less shares his name. He went to a place which reflected and reinforced who he already thought he was. But he brought that extra letter, that ע which represents vision -- and with that vision, was able to see his encounter with a stranger as a wrestle with God, and able to receive the blessing of expanded consciousness which comes with that wrestle.

May we be able to do the same.

November 15, 2013

The nighttime wrestle - a pearl of Torah for Vayishlach

In this week's Torah portion, Vayishlach, Jacob wrestles with a stranger all night until dawn and receives a new name as a blessing. I'll say more about that in the d'var Torah I'm offering on Shabbat at my shul (which will be posted here on Sunday, as usual.) Today I'm sharing a tiny teaching adapted from the Degel Machaneh Efraim, the grandson of the Baal Shem Tov.

In the line "a man strived with him until dawn," the Degel sees a reference to how each of us will struggle in life -- with our impulses and inclinations. Each person has two impulses or inclinations, the yetzer ha-tov (good inclination) and the yetzer ha-ra(bad inclination.) We enter the world, he says, as holy souls, and the evil inclination has no sway over us. But this inevitably changes as we grow up and move into the working world, and we come to imagine that there are things we "have to do" to make a living. He lists lying or cheating others; I suspect each of us can think of times when we've justified choices about which we secretly don't feel so great.

Each of us will experience struggle with our own yetzer ha-ra -- and the struggle may be fiercest, somehow, during the black of night. All of our troubles, fears, and anxieties feel worse during the night. (Anyone who has struggled with insomnia knows this all too well.) But when the dawn comes, he says, our struggles are illuminated and we can recognize things for what they are.

A blessing for all of us: during these last days of parashat Vayishlach, may we be gifted with light which illuminates our troubles and our mistakes so that we can see them clearly and can emerge unafraid.

Shabbat shalom!

November 13, 2013

Ten-plus years of Velveteen Rabbi

Whoops! I missed my tenth blogiversary.

Whoops! I missed my tenth blogiversary.

It was sometime in October. I meant to make a post celebrating ten years of Velveteen Rabbi, and I just...forgot. Maybe that's appropriate, since I'm not sure what day I actually started. (This blog was briefly hosted at blogspot, and then I discovered that blogspot didn't have commenting capability built in -- and what's the point of a blog with no conversation? -- so I moved to TypePad, copied my first few posts to their new home, and have been here ever since.)

The simple fact that I've spent ten years writing regularly feels like a victory. I remember hearing, at the end of my MFA journey at Bennington, that many MFA grads are no longer writing by ten years after the completion of their programs. I'm proud to be able to say that fourteen years after I got my MFA, I'm still writing poetry regularly -- and still reviewing books regularly -- and still engaging in the writing life as a daily and weekly practice. This blog has surely been a big part of that.

Many of the blogs I remember reading when I first got started have gone dark or defunct, succumbed to linkrot, or disappeared entirely. Beth Adams' The Cassandra Pages is a notable exception. So is Dave Bonta's Via Negativa. Dale Favier's mole was around back then, and is still vibrant. Lorianne DiSabato's Hoarded Ordinaries is still going strong. I know that Rabbi Josh Yuter of YUtopia celebrated his tenth blogiversary a while back, as well. (And, of course, my husband Ethan Zuckerman's My Heart's In Accra is still wonderful. Come to think of it, I should thank him for suggesting that I start a blog all those years ago. Thanks, sweetie.) It's a perennial delight to me that I've made so many enduring friends through this medium of curated self-revelation and correspondence, and that those friendships persist both online and offline.

When I started this blog, I yearned to "run and play with the real rabbis" -- hence the blog's name and original tagline. (Which, as I noted in my very first post, was borrowed with permission from cartoonist Jennifer Berman and her wonderful "Velveteen Rabbi" cartoon.) Over the years of this blog's existence, I applied to rabbinic school -- was accepted -- began my formal studies -- posted endlessly about the things I was learning, liturgy and Hasidut and Jewish history and on and on -- and after nearly six years of hard work, made it to ordination. Many of you accompanied me on that journey.

When I set off to spend my summer in Israel, I blogged about it here, and I posted frequently about my adventures both challenging and sweet. That was 2008, the same year that TIME named VR as one of the top 25 sites on the internet. I also blogged here when I had my strokes. And when I put forth my chapbook of miscarriage poems. And when our son was born. I posted a few years' worth of weekly Torah poems here, which later coalesced into my first book, 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia 2011.) I posted a full year of weekly mother poems here, which later coalesced into my second book, Waiting to Unfold (Phoenicia 2013.)

I didn't use categories to sort my posts when I started out (instead I used Technorati tags -- remember those?), but I started to do so pretty soon. My tag cloud tells me that the things I post about most frequently are Torah and poetry; community, prayer, and the daily round are the next on the list. That sounds about right. I've made 2,452 posts (so far) and hosted 10,880 comments. (Not bad.)

I've heard a lot of people say that the golden era of blogs has passed, giving way to Twitter and Facebook and instagram and other forms of bite-sized, mobile-phone-accessible communication. People don't have the patience to read long-form blog posts anymore, nor to enter into sustained conversations in the comments sections. Today's internet isn't interested in the substantive or nuanced -- at least, that's how the conventional wisdom goes. That may be true, by and large. But some of us are still writing, and still reading, and still conversing. Maybe long-form blogs are like poetry: not everyone's cup of tea, requiring as they do a fair amount of focus and attention, but endlessly rewarding for those who choose to take part.

Thanks, everyone, for being a part of Velveteen Rabbi for the last ten years and a bit. Here's to many more.

Perhaps also relevant: my list of Favorite Posts.

Image source: this post, which attributes the image to "anonymous."

November 12, 2013

Answers to good questions

I posted last week about being interviewed by the readers of Rachel Held Evans' prominent Christian blog. As is her custom, Rachel posted a short bio and then opened the floor for her readers to ask questions. Out of the questions they asked, Rachel chose eight for me to answer, and they're terrific (and substantive) questions:

Are there any common assumptions that Christians tend to make about Jews that bug you?

Who do you feel you have more in common with religiously - Christians who take a progressive/liberal theological approach to their faith similar to the way you approach Judaism, or Jews (conservative or Orthodox) who take a significantly more literal/conservative approach to the Jewish faith than you do?

How do reformed Jewish clergy address the questions raised by the historicity of scripture? For example, the Exodus clearly plays a significant role in the scripture, yet no historical evidence exists that it actually happened.

I'm interested in reading about the Bible from a Jewish perspective but don't know where to start. I love the idea of Midrash, but the literature seems so vast and I feel overwhelmed. What would you recommend for a Christian who wants to try reading some Midrash?

How do you interpret the passages where God seems to command things that are immoral? As God-inspired for a point in time? Or purely human writing? (i.e. Kill unruly children, Deut 21:18-21; Kill people who work on the sabbath, Ex 35.)

Hi! I was wondering your thoughts on the eschatological views on Israel and the Middle East held by many Christian Evangelicals/ How do they compare with your own views about the end times, and how it relates to present-day Israel/Palestine?

I'd love to hear more about Emerging Jewish and Muslim Leaders. What did you learn about interfaith dialog from that experience? What strategies for productive conversation around religious differences proved most effective from your perspective?

As a clergywoman in a Christian denomination, I wonder what your journey was like – were you always accepted because you were in Reform congregations, or were there still struggles over gender issues?

You can see my answers here: Ask a (liberal) rabbi...Response. Go and read, and feel free to comment here to let me know what you think (and/or to comment over there, or ping Rachel Evans on twitter, to let Rachel Evans know what you think!) I'm grateful to have been invited and I hope my answers shed some light. Thanks, (other) Rachel!

November 11, 2013

On the silencing of Dinah, and rape culture today

This post focuses on an act of Biblical rape, and on silencing and rape in our own world.

If that is likely to be triggering for you, please feel free to skip it.

That same night, he got up, took his two wives, his two maidservants, and his eleven children, and crossed at a ford of the Jabbok. (Bereshit/Genesis 32:23, in this week's Torah portion, Vayishlach)

I'll say more about Jacob's encounters on the banks of the Jabbok in my d'var Torah this coming Shabbat. (If you don't live locally and can't make it to services, never fear, I'll post it here on Sunday.) Today I'm focusing on a different aspect of the parsha. Note that Torah refers here to his eleven children, but we know that Jacob had twelve children at this point -- eleven boys, plus Dinah. Why, then, does Torah say eleven? Rashi explains, quoting Midrash (Bereshit Rabbah) that Jacob hid Dinah in a box so that Esau would not see her and seek to marry her. Jacob was so afraid of his twin brother's animal appetites that he concealed Dinah in a coffin to keep her safe.

I'll say more about Jacob's encounters on the banks of the Jabbok in my d'var Torah this coming Shabbat. (If you don't live locally and can't make it to services, never fear, I'll post it here on Sunday.) Today I'm focusing on a different aspect of the parsha. Note that Torah refers here to his eleven children, but we know that Jacob had twelve children at this point -- eleven boys, plus Dinah. Why, then, does Torah say eleven? Rashi explains, quoting Midrash (Bereshit Rabbah) that Jacob hid Dinah in a box so that Esau would not see her and seek to marry her. Jacob was so afraid of his twin brother's animal appetites that he concealed Dinah in a coffin to keep her safe.

That may seem ironic when we reach the very next story: Dinah's encounter with a local man named Shechem, which some translations call seduction, though most translations name as rape. Afterwards, Torah tells us, Shechem falls in love with her, speaks tenderly to her, and sends his father Hamor to procure her as a wife. Later in Exodus 22:15 we will read that "If a man seduces a virgin who is not engaged to anyone and has sex with her, he must pay the customary bride price and marry her" -- perhaps a troubling practice, to our modern sensibilities, but apparently an accepted one in the ancient Near East. And that's exactly what Shechem does.

But Dinah's brothers, outraged by this act of violence against their sister, devise a plan. (Some have argued that they were more outraged by Shechem's non-Israelite status and by their sister's act of premarital intercourse than by the suggested marriage -- see Dinah: Bible at the Jewish Women's Archive.) They explain that they couldn't marry off their sister to a man who isn't circumcised. They say to Hamor that if every man in the village will agree to be circumcised, then they will let their sister marry into this community. Then, when every man in the village is incapacitated and healing from this elective surgery, the brothers slaughter all of them. They kill every male in the village, and take their wives and children as captives. They take all of the wealth and livestock which belonged to that village.

Throughout this narrative, Dinah never speaks once. Her voice is entirely absent from the black fire of our text.

In order to hear Dinah's voice, we look instead to the white fire. Some classical midrash argues that Dinah becomes the wife of Job, which is regarded as a punishment for Jacob since he withheld her from Esau. (How Dinah's ensuing suffering is seen as a punishment for her father but not for her is a sign of her invisibility in her own story.) Another midrash suggests that she gives birth to a daughter who is taken by the archangel Michael to Egypt, and raised by a childless Egyptian priest, and becomes known as Asenath, daughter of Potiphera: the woman who will marry Joseph. In that version there's a kind of redemption for Dinah's child, if not for Dinah herself.

Anita Diamant's midrashic novel The Red Tent gives voice and agency to Dinah, showing us a Dinah who genuinely loved Shechem and hoped to be his bride. In that version of the story, after the slaughter, Dinah escapes to Egypt, gives birth to a son, and eventually reconciles with her brother Joseph. It's still a difficult story, rife with violence -- the slaughter, sacking, and plunder of that entire village -- but in Diamant's imagining, Dinah is a whole, vibrant human being who tells her own story as she understands it. Reading that book felt to me like a tikkun, a healing, because it gave Dinah voice. But I know that it's a reading which goes counter to the ways my tradition has usually read this story.

In Torah, Dinah is silent (or silenced.) And Dinah is raped. I believe that these two acts of violence against women are connected.

Think of all the times and places in human history when women haven't been able to tell our own stories. That silencing constricts our freedom as surely as Jacob's box constricted Dinah's. The people and the structures of power responsible for silencing us may think they're keeping us "safe" -- but in this week's Torah portion, we see that keeping a woman hidden or silent offers no protection. If you read the text as most of our commentators have read it, Dinah is raped by a stranger. If you read the text through Diamant's (and the JWA's) feminist lenses, giving Dinah agency in this act of unmarried sexuality, there's no rape -- but Dinah's trust is violated by her brothers and their acts of violence. Either way, her silence does not help her.

How might her story have been different if Dinah had been allowed to participate wholly in the journeying of her family -- if, like her brothers, she had been able to walk freely in the open air -- if, like her brothers, she had been given a voice to speak out or talk back or tell it as she saw it? How might our stories be different if every woman in the world were granted those freedoms as a matter of course? Dinah's story challenges us with its very familiarity. A woman, rendered invisible and silent. A woman, raped. Maybe the only upside here is that the ensuing violence of the "honor killing" is directed against Shechem and his people, and not against Dinah herself... but I find that to be scant comfort indeed.

Some of the structures which silence women today are almost invisible. Societal expectations, peer pressure, the desire to be liked, the fear that if we speak what's true for us we will be shunned or left alone -- not to mention the outrage and active silencing coming from men who don't like it when we get uppity. (Don't believe me? Try The Unspoken Rules that Silence Women in Leadership; Michigan Women Lawmakers Silenced By GOP After Abortion Debate 'Temper Tantrum'; 700 Texans gather for 'People's Fillibuster,' GOP Lawmaker Tries to Silence ‘Repetitive’ Testimony; Six insidious ways social media can be used to silence women. Those are just a few links; there are many more.)

Rape itself is a tool frequently used to keep women silent. (See Breaking the silence: addressing rape culture in America; see Rape Culture Exists: An Open Letter, posted just this week; see 50 facts about rape.) Every two minutes, a sexual assault takes place in America, and most of the victims are women. Around the world, one in three women has been abused, beaten, or coerced into sex. And most of these stories are never told, because girls are taught -- in ways both obvious and subtle -- that if we speak out, we will be punished further. We have learned that it is safer to remain silent.

These structures of oppression are hard to dismantle. But that doesn't give us a pass on dismantling them all the same. I know that the Pirkei Avot line "It's not incumbent on us to finish the task, but neither are we free to refrain from beginning it" has come to feel like a hoary old chestnut, it's quoted so often -- but it's still true. We are not free to refrain from this work.

How can we honor Dinah, the silent twelfth child of Jacob? By changing the world we live in so that it is no longer one in which this story could happen.

Get informed about rape. (See Ten Things to End Rape Culture, the Nation. Or Women's Rights, Amnesty International, which focuses on the rights of women in the Middle East.)

Learn about how women are silenced -- and how we learn to silence ourselves. (See, e.g., Silencing the Self: Women and Depression by Dana Jack.) Commit to seeking out, and to really hearing, women's voices.

Make a particular effort to be attuned to the voices of women of color and transwomen, who frequently experience doubled silencing and oppression. (See An Open Letter to the White Feminist Community; see Silence Kills.)

Support your local rape crisis center or hotline, so that rape victims get the care and support they need. And challenge the culture in which it's ostensibly reasonable for a woman to be silenced or assaulted, so that there will be fewer rape victims in need of that support.

When people tell rape jokes, ask them to stop. (Captain Awkward has some suggestions on how to do that.) Rape isn't funny. Ever.

Recognize that the way to stop rape is to stop rape, not to constrain the actions or behavior or dress of women.

Educate your children -- of any gender -- about human dignity and about consent. (I highly recommend Ask Moxie's post about this: A Letter to my Sons About Stopping Rape.)

Dinah's story calls us to stop the silencing of women, to stop violence

against women, to change the whole system in which rape and violence and

shaming and silencing happen. We can create a different world. And we must.

Image source: "Looking out of the red tent" by Renee Kahn.

My thanks are due to everyone who responded to my tweet earlier today asking for suggestions of actions we can take to end rape culture and the silencing of women.

November 7, 2013

First come the questions...

Christian writer (author of A Year of Biblical Womanhood) and blogger Rachel Held Evans does a lot of interesting things with her blog. Last year, for instance, she ran a series of posts exploring the Biblical figure of Esther through a variety of lenses, and she asked me to contribute an essay, which I did: Esther, Actually: A Jewish Perspective. It was a neat chance to share Jewish interpretations of Esther with a wide group of Christian readers.

Another of her projects is the Ask A... series, in which she invites people with different perspectives (a universalist, a mixed-faith couple, a stay-at-home dad, a transgender Christian) to be guests on her blog and to take questions from her readers. Her (many) readers post questions, and give thumbs-up to the questions they like best; out of the questions she receives, she chooses 6 or 7 to send on to the person being interviewed, and that person gets to answer the questions on her blog.

She graciously asked me to return to her blog as part of the "Ask A..." series, and I said sure, why not. Here's the question post: Ask a (liberal) rabbi. I'm curious to see what sorts of questions I get, and I hope and pray that I can answer them wisely and well, in a manner which gives honor to my teachers and those who have helped me learn along the way! Stay tuned -- I'll post about this again once I've answered the questions...

November 6, 2013

God is in this place: short thoughts on Vayetzei

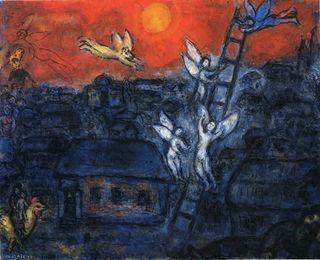

At the start of this week's Torah portion, Vayetzei, Jacob camps for the night and rests his head on a stone. He dreams of a ladder planted in the earth stretching up to heaven, with angels ascending and descending constantly.

At the start of this week's Torah portion, Vayetzei, Jacob camps for the night and rests his head on a stone. He dreams of a ladder planted in the earth stretching up to heaven, with angels ascending and descending constantly.

I like to read the angels as a metaphor for how our attention and intention and prayer flow upward to God, and God's attention and love and blessing flow back to us. After this summer's quantum physics and kabbalah class, I can also read this passage as a metaphor for electrons ascending into an excited state and then falling back down again.

When he wakes, Jacob exclaims, "Truly, God is in this place, and I -- I did not know it!"

How often do we have the experience of being startled out of our complacency into a sudden visceral realization that this moment, right-here-right-now, is holy? Maybe when you see a spectacular sunrise -- or witness a mighty waterfall -- or stand beneath a chuppah with your beloved to exchange vows -- or give birth to a child. And those are indeed moments when we may find ourselves especially open to connection with the Holy One of Blessing.

But it's also possible to experience God's presence in mundane moments. When you wake from a dream, eyes still gritty with sleep. When you're standing in line at the grocery checkout counter. When your child is throwing a tantrum because you didn't let them go outside in the cold without a coat on. Truly, God is in this place, and I... I tend to forget. I know that I tend to forget.

But we can always choose to remember. How would your day be different if you printed this reminder and stuck it to your computer, if you affixed it to your fridge with a magnet, if you found some way to keep reminding yourself: God is in this place. And this place. And this place. Even in our sorrows and anxiety, God is there, if we can only remind ourselves to take notice.

Art: Marc Chagall, Jacob's Ladder, 1973. Also worth reading -- and on the theme of finding holiness even in the mundane details of parenthood (tantrums and all) -- is R' Phyllis Sommer / ImaBima's post TorahMama: Vayetze.

Previous years' divrei Torah for Parashat Vayetzei:

2006: Dreams, vows, and changes (originally published at Radical Torah)

2007: Wellsprings and dreams

2008: Dream [Torah poem]

2009: Hatch [Torah poem]

November 5, 2013

Tales of rabbis in love

Back when I first took 70 faces on the road, I met a woman named Marilyn, in Montreal. She wanted to interview me and my spouse together for a forthcoming book on rabbinic marriages. The interview never took place, for a variety of reasons (mostly our lack of availability!) but the book is now out. It's called Rabbis In Love (LoveWise Publishing, 2013) and it was created by Marilyn Bronstein and Philip Belove. Here's part of how they describe the collection:

Rabbis aren’t monks. They fall in love, they marry, they have families. It’s expected. Jewish spirituality is rooted in daily family life; the joy, the passion, the tears, “the whole enchilada”, or as Jews would say, the whole megilla.

In the introduction, the editors tell the famed Talmudic story about the man who hides under his rabbi's bed in order to learn not only the Torah the rabbi is teaching in the classroom, but also the Torah he is teaching in the mundane acts of his ordinary life -- as the saying goes, "how he ties his shoes."

Of course, the student under the bed gets an earfull of precisely what you'd imagine, and at a certain point the student exclaims in surprise. The rabbi, startled, asks, "What on earth are you doing under the bed?" And the student replies, "This too is Torah I need to learn." It's an apt beginning for a book which features interviews about precisely this kind of Torah: the Torah of intimate relationships.

These are interviews, printed in two voices -- well, really, four: the voices of the editors, and the dual voices of the couples. And the interviews are interspersed with short reflections from the editors about what they felt they'd learned from each interview.

I gravitated toward the chapters featuring rabbis whom I already knew -- Rabbi Shefa Gold and Rachmiel O'Regan, whose music and drumming I have long enjoyed; Rabbi Nadya Gross and Rabbi Victor Gross, two of my beloved rabbinic school teachers (I chuckled at Reb Nadya's story about telling her mother "this is the man I'm going to marry" -- family legend has it that my mother did the same thing after meeting my dad when they were teenagers at summer camp), Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan and Charles Kaplan. I enjoyed encountering familiar voices on the printed page, and gaining some new insights into the lives of my teachers and friends.

The editors describe this as a book for anyone who's interested in love relationships and what we can learn from them. I think that's probably true, though I suspect it might be somewhat inaccessible at times for non-Jewish readers. I also suspect that it might challenge non-religious readers; unsurprisingly, these are couples with a high level of religious observance! But for those who are interested in the details of romance and marriage and what makes relationships work, especially when religion is a potent ingredient in the mix, this book might be your cup of tea. Kol hakavod to the book's creators for bringing their vision to life!

November 4, 2013

Interview at A Little Yes

I'm not sure when I started reading Heather Caliri of A Little Yes, though I think it was around the time that she moved with her kids to Argentina for six months. I've enjoyed vicariously sharing her adventures and looking through her window on the world -- and I'm frequently moved by her (Christian) perspectives on the intersections of faith and parenthood.

So I was delighted when she asked to interview me. Here's a glimpse of our conversation:

You’re a poet, and often write liturgical poems; what parallels do

you see between the practice of faith and the writing of poetry?

I would say that both require me to get out of my own way. They both

require a trust that if I pour out my heart, something good will come.

And in both, it’s okay if things aren’t perfect on the first try.

One of the reasons I love that morning prayer I use is the verse,

“Great is your faithfulness.” That somehow implies that God has faith in

us. Which is wild—we would only think the opposite.

But thinking that God has faith in me as a person, a mother, a poet,

there is something greater than me that has faith in my endeavors...

You can read the whole thing here: On the road to ordination: wildflowers, grief, and the joyous faithfulness of God. (By the by, these interviews are a long-running series on her blog; you can see some of her favorites linked from her Best Of page.)

Thank you, Heather, for a thoughtful and sweet conversation and for this lovely interview post.

November 3, 2013

A poem sparked by parashat Toldot

A new Torah poem of mine has been published at Palestinian Talmud. It arises out of the Torah portion we just completed, parashat Toldot, and it's called "Looking for Water." Here's how it starts:

1.

Isaac dug his father’s wells anew.

This doesn’t mean he just treaded old ground.

Avraham had plumbed the earth’s deep wisdom.

Where his pick struck soil, compassion poured.

Isaac opened up his father’s pipes

so kindness, long-delayed, could flow again.

In all who drank, a memory arose:

water, shared in the desert, saves a life...

Read the whole thing there: Looking for Water: a [poetic] drash for parashat Toldot.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers