Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 169

January 15, 2014

How to love while acknowledging flaws

I've been thinking lately about how to love something while acknowledging its flaws. A few years ago I read a thought-provoking speech by Wendy Doniger which touches on this. Here's an excerpt. (She's talking here about hermeneutics, which means "a way of reading" or "a way of interpreting.")

I've been thinking lately about how to love something while acknowledging its flaws. A few years ago I read a thought-provoking speech by Wendy Doniger which touches on this. Here's an excerpt. (She's talking here about hermeneutics, which means "a way of reading" or "a way of interpreting.")

We need to balance what literary critics call a hermeneutics of suspicion -- a method of reading that ferrets out submerged agendas -- with a hermeneutics of retrieval or even of reconciliation (to borrow a term from the literature on the aftermath of genocidal wars in Africa and elsewhere). And this must include some sort of reconciliation to our own shameful American agendas, our own relationship with slavery and with the destruction of the native Americans, not to mention our present imperialism. And then we can begin to read our own classics differently, with what the philosopher and theologian Paul Ricoeur called a second naiveté: where, in our first naiveté, we did not notice the racism, and in our subsequent hypercritical reading we couldn’t see anything else, in our second naiveté we can see how good some writers are despite the inhumanity of their underlying worldviews. If their works really are great literature, they will survive this new reading.

-- Wendy Doniger, "Thinking More Critically About Thinking Too Critically"

I first read Doniger's address in a rabbinic school class called Moadim l'Simcha ("Seasons of Rejoicing"), a two-semester cycle of deep immersion in Hasidic texts. We aimed to explore and unpack some of the tradition's many teachings about the festival cycle. It was an amazing course, not least because the Hasidic texts themselves were amazing and rich and I return to them often.

And I also return often to this idea of Doniger's. It's a useful lens for reading Hasidic material, because that material is inevitably a product of the times and culture which produced it. In its presumptions about gender roles and about the inherent spiritual superiority of our own people, that literature can be problematic to a modern, cosmopolitan, feminist sensibility. What do we do with that, we who strive to be modern, cosmopolitan, feminist and who also yearn for the spiritual sustenance which those texts often contain?

That's where Doniger's idea of a hermeneutics -- which is to say, a mode of interpretation, or a way of reading -- of reconciliation comes in. We do ourselves no favors, and we do our tradition a disservice, when we blind ourselves to what's problematic. But we also do ourselves and our tradition a disservice when we take only the step of recognizing what's problematic, and fail to take the next step of balancing and reconciling what's problematic with what's beautiful, meaningful, and useful in the text at hand.

Maybe I'm revealing myself here as the Hegelian thinker my undergraduate education taught me to be. I'm always less interested in thesis and antithesis than in synthesis, the third step which bridges and transcends the binary. This thing is beautiful -- no, it's problematic -- no, it's both at once, and having acknowledged that, now I can interact with it in a different way. Indeed, maybe it's interesting and rich and thought-provoking precisely because it is both beautiful and problematic. Maybe I can learn something about it, and about myself, through engaging both with its beauty and with its problematic aspects.

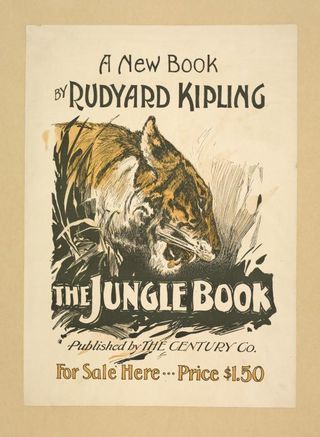

Almost anything worth engaging with is both beautiful and problematic. Most great literature, for instance. Doniger cites some fine examples, among them Rudyard Kipling, who was notably racist and imperialist and yet wrote some extraordinary work. Heidegger wrote tremendous philosophy and was also a Nazi. Ezra Pound wrote great poetry and was also an anti-Semite. And so on. I don't want to deny what's problematic -- in Kipling's work, in Heidegger's, in Pound's. But I think there's value in unearthing what we can still benefit from, what we can still love, even in a work that's flawed. It's a different kind of love, once you've gone through the process of realizing that the thing you loved isn't perfect but is still worth your time.

Almost anything worth engaging with is both beautiful and problematic. Most great literature, for instance. Doniger cites some fine examples, among them Rudyard Kipling, who was notably racist and imperialist and yet wrote some extraordinary work. Heidegger wrote tremendous philosophy and was also a Nazi. Ezra Pound wrote great poetry and was also an anti-Semite. And so on. I don't want to deny what's problematic -- in Kipling's work, in Heidegger's, in Pound's. But I think there's value in unearthing what we can still benefit from, what we can still love, even in a work that's flawed. It's a different kind of love, once you've gone through the process of realizing that the thing you loved isn't perfect but is still worth your time.

The same goes for the science fiction I read as an adolescent. I devoured those books, which opened up amazing new worlds for my imagination to explore! And then in college I came to realize that most of those books aren't perfect, and might even be actively problematic. (Much of that early SF is sexist in ways I didn't notice as a kid, but can't help noticing now; and some of the politics around sexuality and gender expression make me actively wince.) So do I junk those books? Or is there a way to approach those books now with that "hermeneutics of reconciliation," a way of reading which recognizes the flaws but presupposes that there's something there worth redeeming?

Or for that matter, the ur-text at the heart of my whole tradition. As a rabbi, and as a Jew, I claim Torah as the story at the heart of my life and practice. There's one way of reading Torah which focuses on Torah's beauty, its poetry and ethics and narrative encoding our attempt to express in words an encounter with divinity. There's another reading which says that Torah's problematic aspects -- patriarchy, xenophobia, condoning of violence against outsiders -- annul its good sides. But the third reading, the redemptive reading, the reading through that lens of reconciliation that Doniger talks about: that's the reading that interests me most.

This kind of reading takes work. Those of us who love Torah have to be willing to complicate our love of Torah by allowing ourselves to recognize the parts of Torah which are problematic. (For instance, how Torah has been used -- I would say mis-used -- to justify oppression and violence.) And those who mistrust Torah have to be willing to complicate that mistrust by allowing themselves to recognize the parts of Torah which are transcendent and beautiful. (In many ways that's the tougher sell. How would I go about convincing someone who feels wounded by Torah that it's worth engaging with the very text they feel has empowered people to hurt them?) But if we can find our way to this kind of reading, it comes with tremendous rewards.

The Hasidic master known as the Me'or Eynayim ("The Light of the Eyes") wrote the following:

You struggle and find the light that God has hidden in God's Torah. After a person has truly worked at such searching, it comes to be called her Torah.

(Okay, he said "his Torah," not hers, but I'm permitting myself that liberty in translation to make the text feel more like it applies to me.) Sometimes we have to struggle to find the light -- but it's through the struggle that the Torah becomes truly our own. And we have a richer experience of reading, once we're willing and able to do that work. When we approach the Torah with an understanding that it's troubling in places, but also with an understanding that there's light hidden in it for those willing to seek, we open ourselves up to the possibility of experiencing that light more wholly than we would if we pretended that there was nothing about Torah which challenges us.

It's unfortunate when people fail to notice what's problematic -- or, worse, willfully blind themselves to what's problematic. (In the Torah, or in the literary canon, or in -- anything, really.) But it's also unfortunate when people fail to notice what's beautiful, or when people overfocus on what's broken and miss what is whole. Both of those lenses are always necessary. And even more necessary is the bridge between the two: not either/or, but both/and. Yes, it's wonderful; yes, it's flawed; so now that we're holding that tension, what new fruitfulness becomes possible? What new understandings can we glean now that we're balancing what's beautiful with what's broken, acknowledging both but allowing neither one alone to be the whole story?

The fact that I'm interested in going beyond what's problematic to find the more nuanced kind of interest on the other side is a sign of a certain kind of privilege. I have the luxury of wanting to find a redemptive reading of Torah, because no one's ever used Torah against me. I have the luxury of wanting to find a redemptive reading of Kipling, because I'm not directly impacted by the racism and the imperialism which suffuse his work. (And so on.) I understand that some people never move beyond the initial step of seeing the good in something -- and others never move beyond the second step of seeing the damage and brokenness in that same thing. But I always aspire toward step three.

The reason I aspire toward step three is that I think there's something really spiritually valuable in the act of pursuing this hermeneutics of reconciliation. There's something potentially life-changing about embracing the possibility of finding, or creating, a redemptive way of seeing whatever's at hand. Torah -- literature -- even the nation in which I live -- all contain the problematic alongside the beautiful. And I think all of these things grow infinitely more interesting and meaningful when we're willing to acknowledge both their values and their flaws, and to find that new way of reading which doesn't erase either what's positive or what's negative but builds on both.

What would it look like to take this on as an active and intentional spiritual practice -- the work of seeking a way of relating (to a person, a work of art, a piece of scripture, a nation) which moves beyond the first flush of unalloyed love, and beyond the second response of unalloyed rejection, to a new way of seeing, which both integrates and transcends the good and the bad?

Real World Halachic Issues in a Time of Paradigm Shift

This morning brought another program I was really excited about -- a plenary panel called Real World Halachic Issues in a Time of Paradigm Shift, introduced and facilitated by my dear friend and teacher Rabbi Daniel Siegel. Last year's session Halakha : Honoring the Past, Finding Our Way was a highlight of the conference for me. I knew this session would be, too.

Last year, we heard from several speakers who offered different Renewal takes on a single issue. This year, we heard from several speakers, each of whom touched on a different issue in contemporary Jewish life. Each ALEPH-ordained rabbi is requited to write a teshuvah -- a rabbinic responsum to a real, living halakhic question -- in order to receive smicha. The sesson featured three of our colleagues presenting about their teshuvot, each of which was on a different subject.

Rabbi Ephraim Eisen spoke about his teshuvah on Burying Cremated Remains in a Jewish Cemetery; Rabbi Simcha Zevit spoke about her work on Choose Life / Do Not Prolong Death: A Question on Feeding Tubes; and Rabbi Jeremy Parnes offered a précis of his teshuvah Intermarriage Under a Chuppah? Renewing the Ger Toshav. (Ger toshav is the Biblical Hebrew term denoting a stranger or outsider who dwells among us.) Here are some notes and reflections from how the morning went.

Rabbi Daniel Siegel begins, "Last year I said in my introduction to the first of these sessions that we needed to re-expand the halakhic table. Rabbi Ethan Tucker talks about this in Core Issues in Halakha -- how a decision was made by the Orthodox rabbinate in the late 1800s to withdraw from the larger Jewish community and take their share of governmental money and form their own Orthodox chevre, and that was as though they took the leaves out of the table and took the extra seats away and put them by the wall, and they said, we'll just do halakha to people who are already committed to our way of living."

Rabbi Daniel Siegel begins, "Last year I said in my introduction to the first of these sessions that we needed to re-expand the halakhic table. Rabbi Ethan Tucker talks about this in Core Issues in Halakha -- how a decision was made by the Orthodox rabbinate in the late 1800s to withdraw from the larger Jewish community and take their share of governmental money and form their own Orthodox chevre, and that was as though they took the leaves out of the table and took the extra seats away and put them by the wall, and they said, we'll just do halakha to people who are already committed to our way of living."

Last year I said that we need to put the leaves back into the table, pull up the chairs, and sit down to join the conversation. One of my favorite examples of that was that one of the first teshuvot that was written here was by R' Eyal Levinson -- a halakhic piece which legitimizes same-sex marriages [pdf]. He told me it couldn't be done, and I said if it couldn't be done then halakha is useless because it doesn't speak to the issues of our time. So he took it on. And now it's inside the conversation.

People often ask: why bother with the halakhic conversation? Why not just say, this is right so this is what we're going to do?

By way of beginning his response, he talks about the body of teshuvah literature, the records of all of the questions that congregational rabbis asked their rabbis. And he notes that when we read such a document, we understand that the rabbi who writes a given teshuvah is not saying that his answer is exhaustive. Sometimes the answer is, "This [thing X] is absolutely something which we should be doing, and, every community is going to have to make their own decision."

It doesn't matter what the answer is. The question "what's the halakha on" is almost tangential to the real process, which is to say: how do we evaluate the relationship between the principles and precedents of the past in relation to this specific moment? The most important thing is to be aware of the situation and to do the best we can, and participate in the conversation.

The halakhic conversation is about this underlying question, which is always the generic question underneath: how do I respond to this moment, or how do I perform this action, in such a way that it is connected to the revelation of our purpose at Sinai and contributes to the process of our redemption in the future?

He asks, "What do I have to do, as a Jew, to mark myself so that I stay connected, so that I can be a beacon to people to move them forward?"

He quotes Rabbi Hannah Dresner: "We are lovers, and our pillow talk, the language of our love, is our exchange of Torah. God speaks the written word to us, and we return the flow of God's love by listening and answering empathically as any lover would. We offer pilpul, extrapolations of Jewish law, as we struggle to discern how...to build in our response on what our lover has shared." And then he continues:

We have to do for halakha what Rabbi Akiva did for halakha many years ago. He said, in order for halakha to be relevant we have to have a new way of pulling meaning out of the Torah so that every letter can be used to hang halakhot on. That was a paradigm shift moment. There had to be another way. And now, as Reb Zalman has suggested to us, we need this new concept, integral halakha, to expand the halakhic conversation, so that we can be both backwards-compatible and forward-looking at the same time.

He explains that asks each student to construct a question, most often out of something in their own lives, which is: how do I respond to this particular situation in this particular moment in a way that connects me to both ends of the continuum that I see myself on. Today we'll hear from three rabbis on their teshuvot. Others are forthcoming, in written and edited form -- stay tuned. Meanwhile, we move on to hearing from our three panelists for today.

Rabbi Simcha Zevit begins by noting that often our congregants come to us seeking affirmation that a decision they're already making has a place within Jewish tradition. She cites Reb Zalman's metaphor: that as we saw our place in the universe broadened and shifted in 1968 once we were able to see the earth from space, we need now to see Judaism and its practice in a way that includes the widest lens of understanding. "We look to Torah, Talmud, halakhic codes and more current halakhic works -- and we include current societal norms, scientific knowledge, and so on, to redefine a contemporary Judaism that's doable for Jews who wish to stay true to our tradition and allow it to be reinterpreted for our time."

Integral halakha takes this paradigm shift, this wide-angle lens, into account. And it's based on our understanding of divine will. The ultimate purpose of halakha is not only defined by an outer authority; God's will is also revealed through our personal experiences. In the old paradigm we said that halakha was rooted in a transcendent God, God Who lives outside of ourselves. Now the paradigm shift includes an emphasis on the inner experience of God, and we look to manifest our understanding of what's required of us through our actions in connection to our understanding of tradition.

"This doesn't mean that each person operates on his/her own, doing whatever they feel is right and calling it halakha, the Jewish way. Judaism always has been a religion that's rooted in strong community. If we're undergoing a shift that allows personal experience and understanding to be a basis for decision-making, how then do we move to communal norms?" She cites Reb Zalman's teachings about the consensus of the committed. She notes that our tradition always offers for more than one choice, and argues that we want to cast the broadest possible net so that our people may be affirmed in their authenticity as Jews.

"This doesn't mean that each person operates on his/her own, doing whatever they feel is right and calling it halakha, the Jewish way. Judaism always has been a religion that's rooted in strong community. If we're undergoing a shift that allows personal experience and understanding to be a basis for decision-making, how then do we move to communal norms?" She cites Reb Zalman's teachings about the consensus of the committed. She notes that our tradition always offers for more than one choice, and argues that we want to cast the broadest possible net so that our people may be affirmed in their authenticity as Jews.

Her question is about nutrition and hydration at end of life. Advances in recent medical technology allow us to prolong life, and in turn raise new questions about that prolonging of life. We can send nutrients directly into the abdomen for those who can no longer swallow; respirators breathe for those who can no longer breathe. And this leaves us asking the monumental question: how and when to preserve life, and when to let go. When does continuing life become a source of pain for the patient, and a source of agonizing decisions for those concerned?

The question she addresses in her teshuvah is one which any of us might face. (She notes that the situation she poses was influenced by her own experience of caring for her elderly mother, but that it is also a kind of composite, based on the questions and experiences of others as well.) In this case, the patient's swallowing is compromised, and therefore with continued spoon-feeding she runs the risk of choking or aspiration and pneumonia, either of which would be fatal. But feeding tubes may be a futile intervention, and may go against the patient's wishes. Her question as a rabbi is, "How can I provide the best guidance, using traditional and modern sources -- and how can I be a loving presence, giving the most compassionate support possible?"

The question: I have the power of attorney for my mother, a 75-year-old woman with dementia. Her ability to make decisions about her own care is questionable, as she is confused and doesn't understand the consequences of her decisions. A year ago we discussed these issues when her mind was clearer; we did not sign directives but she said she did not want to prolong her life through technology. We did not discuss feeding tubes. Now my mother has difficulty swallowing and isn't getting sufficient nutrition and hydration. Her doctors want me to decide whether to feed her through a feeding tube. Her health is compromised by dementia, diabetes, and other issues already. Should I refuse a feeding tube?

To begin answering the question, of course, Rabbi Zevit went back to traditional sources. In brief, our sources rest on a number of obligations and assumptions. One is that the preservation of life is of great importance, surpassing almost all of the other commandments. The Talmud is full of examples showing that one must violate Shabbat, etc, if there is the slightest change that human life may be preserved or prolonged -- our own lives, or the lives of others as well. The tradition also shows a duty to heal.

The tradition also assumes that the quality and duration of the life being saved is irrelevant. Life is of infinite, not relative, value. We are created b'tzelem Elohim, and that's paramount. And, traditionally Judaism doesn't support the idea that we have unlimited personal autonomy to make decisions about our health. Our bodies and lives are not always seen as our own, but rather a gift given to us by God for a specific purpose and duration.

The flipside of that is the traditional halakhot which talk about permission to not prolong death. These are sources from Talmud -- the story of Rabbi Chanania whom the Romans burned at the stake, and the story says that his disciples saw him in pain and begged him to open his mouth and inhale so that he would die sooner. He refused to do something which would actively cause his death. But when his executioner took pity and asked if he could remove the tufts of wet wool which had been placed around his heart to prolong his death, Rabbi Chanania said yes, and also promised the executioner that he would have merit in the world to come. This is a story of not actively seeking death, but also not needlessly prolonging death. How do feeding tubes and respirators fit into that tension?

She summarizes her findings: that we have permission to not prolong death-- if someone is terminally ill (and of course there are questions about how to define that, Jewishly and according to modern medical ethics); if the person is in undeniable pain (and this can include mental and spiritual anguish, not only physical pain); and if the patient has clearly indicated that they don't want these treatments, which showcases the importance of advance directives so that the family knows what's wanted and what's needed. "What would it be like for us as Jews to include these conversations in what it means to live as Jews?"

Rabbi Efraim Eisen begins by asking: how many of us have been involved in the burial of cremains? How many of us have officiated at the ceremony of cremation? (Many hands around the room go up, suggesting that for many of us, this is a live issue in our communities today.) "I was called by a woman whom I did not know," he recounts. She had just had a funeral for her father in Florida and wanted to bring his remains to be buried in Rabbi Eisen's cemetery. Rabbi Eisen asked, "what can I do to help you bring his body back?" She said, "It's okay -- my father will travel in the overhead compartment."

Rabbi Efraim Eisen begins by asking: how many of us have been involved in the burial of cremains? How many of us have officiated at the ceremony of cremation? (Many hands around the room go up, suggesting that for many of us, this is a live issue in our communities today.) "I was called by a woman whom I did not know," he recounts. She had just had a funeral for her father in Florida and wanted to bring his remains to be buried in Rabbi Eisen's cemetery. Rabbi Eisen asked, "what can I do to help you bring his body back?" She said, "It's okay -- my father will travel in the overhead compartment."

According to his temple bylaws, they're not allowed to inter ashes in their cemetery. He called colleagues for advice; and the suggestion from colleagues was, tell her you welcome her back into the community and will do a ceremony, but she would do best to take care of the ashes on her own. So that's what they did in that particular instance. But the question had become a live one for him.

In 1960, 3% of people who died in the United States were cremated; in 2010, it was upwards of 40% and is continually rising. One of the biggest reasons, he suggests, is economic. There are also environmental concerns; some people say that cremation is environmentally bad because emissions in the air, but others say, what about land usage issues?

He asked his Talmud chevruta, Edward Feld, about this; Feld suggested that he consult Isaac Klein's A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice (1960.) And that book notes that "The Jewish way of burial is to place the body in the earth. Hence cremation is frowned-upon." Klein's book is a compilation of traditional halakhic practice as well as a compilation of decisions made by the Conservative movement's law committee, and that law committee has ruled that cremation is not permitted. When cremation is done, however, in disregard of Jewish practice, that book says that the ashes may be buried and the rabbi may officiate though only at the funeral home, and the interment may not be conducted by a rabbi lest his presence be interpreted as tacit approval. The fact that the Klein book says that the interment of ashes is actually permitted began a whole new series of conversations.

What does Torah say? The first mention of burial in Torah is the purchase of the cave of Machpelah by Abraham, who came to mourn for Sarah. From this parsha we learn that we have three responsibilities: to mourn, to offer a hesped (eulogy), and to bury. In Devarim 21 we learn that if a man has committed a sin worthy of death and is hanged, you shall not leave him all night on the tree but shall bury him that same day. If burial is required for a person guilty of a capital offense, all the more reason for an ordinary person to be buried as soon as possible. It also seems clear that burial is commanded but the specifics of the burial practice are left vague.

How about the Talmud? The Jerusalem Talmud concludes from this passage in Deuteronomy that we are required to bury the body in its entirety. Burning of corpses, however, is mentioned in several places in the Talmud. Burning of corpses should happen during times of plague, to prevent the spread of infection. Also relevant to this conversation is the killing and desecration of Saul and his sons. Their bodies were taken down from the wall, the bodies were burned, and the bones were buried under a tamarisk tree. Lest we interpret this to mean that the tradition condones cremation, the Radak explains that their flesh had grown worms which is why it was burned.

The Babylonian Talmud argues that cremation is a denial of the belief in resurrection and is a denial to the dignity of the body and to God Who created the body. (Rabbi Eisen adds, "My own thought on that is, if God created everything, then why couldn't God resurrect the body even from dust?") And the Mishna considers the burning of a corpse to be an idolatrous practice, a sign of idol worship. But, Rabbi Eisen asks, "Given the increasing numbers of people looking for cremation, what are we to do?"

When someone comes to him and asks for cremation, he tells us, he tries to listen to their reasons, and then to explain to them the traditional practice, which is burial. But when he's counseling someone who's in the end stages of life, or their family members, he listens more than he talks. "In Brakhot 45a we learn that going out to see what the people are doing is one way to see what the halakha should be."

"Amother principle that comes up strongly in the Talmud is, imagine that I said, no you can't bury your father in our cemetery, and therefore they turn their back on Judaism completely. The principle of 'finding the paths of peace' seems to me to be important."

One option is to set up a specific area in the cemetery for the interring of cremains. (This is a familiar practice to many of us.)

He closes by citing something that Reb Zalman said to a chevra kadisha in May 2001:

I don't want to give you a big green light for cremation. Because a lot of stuf fin Judaism says it's a no-no. But some years ago I published something where I said I wanted my remains to be cremated and the ashes to be taken to Auschwitz. My father was born in Oswiecen, my zaide was a shochet there, and when I was half a year old, they took me to zaide so he should bless me. This has become such a terrible place for us...

One of the reasons why they say no to cremation is because of something that it says in the Talmud. Titus, who had desecrated the Temple, wanted to have his corpse burned and his ashes strewn all over so that God wouldn't be able to call him to judgement. In other words, people who go to cremation won't be resurrected. But if God isn't going to resurrect the people who burned at Auschwitz, I don't want to be resurrected either.

"I believe that it is the job of the rabbi," says Rabbi Eisen, "to direct people to traditional Jewish practice, which is burial." But it's clear that he's found a way to work with those who make other choices, too. And he asks, what is the effect of cremation on the soul and how the soul departs this earth? These are continuing questions.

Rabbi Jeremy Parnes tells us that a few years ago he downloaded a sound file recommended by Reb Daniel of a lecture series by R' Ethan Tucker on halakha. (Tucker is co-founder and rosh yeshiva at Mechon Hadar.) Tucker opened his first lecture as follows:

Your Temple is like a section of pomegranate, says the Song of Songs. About this, R' Shimon ben Lakish says, don't say rakatech [Your Temple] but rekatech [Your empty / emptiness], for even the emptiest among you is full of mitzvot like the seeds of a pomegranate.

In effect he is saying that all Jews, even those who seem empty according to the rabbinic elite, are in fact practicing and committed.

How do we handle the cases of questions arising in real time where in halakha we simply get shut down? How do we maintain boundaries and not enter the inexorable slide down the slippery slope?

How do we handle the cases of questions arising in real time where in halakha we simply get shut down? How do we maintain boundaries and not enter the inexorable slide down the slippery slope?

Reb Jeremy tells the story of receiving an email from a friend, a longstanding community member, faced with a quandary. His son was hoping to intermarry, under a chuppah, in the shul, with their community. The friend's question was: would he (Reb Jeremy) take on the responsibility of explaining to the friend's son why his request wasn't possible? The man and his son had only recently reconciled, and he did not want to risk losing his relationship with his son. "He was asking if I would be the one to alienate his son by explaining that there was no possible way that such an event could be considered."

This young man had removed himself from all things Jewish, Reb Jeremy notes -- in effect saying, "you can't fire me, I quit!" And Reb Jeremy was willing to see him that way too...until he remembered, "even the emptiest among you is like a pomegranate full of seeds." His view of this young man had been transformed by R' Shimon ben Lakish.

This young man might have been understood as the "rebellious son" from the Passover haggadah, the one who asks "what does all this mean to you?" (And the tradition says: "To you," not "to us," which shows that he doesn't consider himself part of the community.) But why would a rebellious son even ask for a Jewish wedding with chuppah? And why wouldn't we see that as him reaching back to the community?

Reb Jeremy's teshuvah seeks to answer the question, Can a Jewish male who is a member of this specific synagogue marry a non-Jewish female under a chuppah in our sanctuary? He wanted to discern: "can halakha respond to the needs of Jews in the 21st century in a meaningful way? We no longer live under the yoke of hegemony. Society today is autonomous. To present unquestioned and unquestionable determinations is only to alienate a generation whose response is frequently, demonstrably, you can't fire me -- I quit."

His synagogue is a small transdenominational group, Orthodox at its founding. Today forty percent of the families are in mixed marriages, and many others have spouses who are Jews by choice. His question speaks to the gerei toshav (strangers who dwell among us) in our community and their status. "I've watched how it's the gerei toshav in our community who are keeping things going for us, who are going into the kitchen...!" (Laughter moves around the room; we're all familiar with that phenomenon.)

We might, he suggests, substitute the term "permanent resident and citizen" for "stranger among us." The ger toshav might be able to be an active participant in Jewish community life. (In this he draws on Reb Zalman's thoughts.) His teshuvah explores how it might or might not be possible for such a wedding to take place and to be kiddushin, sanctified marriage according to traditional Jewish lights. In his teshuvah he explored five substantive questions:

Is halakha, as a specific ruling based on the interpretation of Torah, changeable when circumstances change? Can a Jew have conjugal relations with a non-Jew, providing the latter denounces idolatry and accepts the Noahide laws? Can a Jew engage into a valid contract with a non-Jew? Can the [traditional] ketubah become a true contract, rather than a pledge or bond which doesn't require the signature of the bride? Does this in fact determine whether it is possible to be married under a chuppah in the sanctuary?

He argues that in fact if we do it right, such a wedding needs to be in the chuppah under the sanctuary! Because the contract between the two families is a covenantal relationship which needs to be honored. "My research indicated, to my surprise, that this wedding was possible in this way."

In our break-out group afterwards (I choose to go to Reb Jeremy's session), we talk more about his process and his understandings. We talk about what ger toshav means in different contexts -- how do we understand that term here and now, how have others understood that term over time, and so on. What does it mean to be a "resident alien" within someone else's dominant culture? How might a non-Jew locate themselves within the embrace of our culture, and be absorbed as a resident, and what are the implications of that?

People also talk about differences between civil marriages and Jewish religious marriages, and about the effectiveness or relevance of halakha on people who are not Jewish; about being a majority culture or a minority culture and how that makes a difference; about the kinds of ketubot we use and what it means when they're not halakhic contracts.

It's a really interesting and complicated conversation. Some of us who identify as post-halakhic don't find these categories relevant or useful. Rabbi Burt Jacobson asks, "what kind of a Jewish community do we want to be living in? Does not Torah call us to love all people, and to draw them to Torah -- not only Jews, but all people; isn't that our task in Jewish Renewal?" Some argue that we can understand the gerei toshav as people who choose to become not Jews qua Jews, but part of the community of God-fearers.

Some ask whether we're doing the tradition a disservice in not acknowledging that intermarriage can be a path toward losing continuity and losing the Jewish future. Others note that intermarriage can also be a doorway in, and that one reason that historically the children of intermarriages haven't been brought up as knowledgeable Jews is that the Jewish community used to exile such families from our midst. (And, as a corollary: that it's incumbent on us as people who live in a time of paradigm shift to change our community's paradigm for thinking about these issues.)

We have to stop when the hour for lunch arrives -- but I think we could have spent all day on this, and I'm sure that had I gone to one of the other two break-out groups (the one on cremains and the one on end-of-life issues), I would have found an equally deep, passionate, and thoughtful conversation.

A poem for Tu BiShvat

Psalm 34, verse 8: "Taste and see that God is good."

We make our way into the woods

at the edge of our land, trees webbed

with plastic tubing, clear

and pale green against the snow.

Down to the beaver dam, pond

punctuated with cattails,

galvanized tin bright

against grizzled trunks.

Dip a finger beneath the living spigot.

At every sugar shack across the hills

clouds of fragrant steam billow.

And after long boiling, this amber...

Where I grew up, the air is soft

already, begonias thinking

about blooming. Here, this

is what rises, hidden and sweet.

In honor of Tu BiShvat which begins tonight at sundown, here's a poem about the sap rising. It's a revision of a poem I shared here a few years ago.

Enjoy the full moon. Here's to the sap rising -- in our trees and in our hearts!

Here we are, God; send us

In the haftarah (prophetic) reading assigned to this week's Torah portion, Isaiah has a vision of God. In his vision, God asks, whom shall I send, who will go for us? And Isaiah says, "Hineni, here I am! Send me!"

In the haftarah (prophetic) reading assigned to this week's Torah portion, Isaiah has a vision of God. In his vision, God asks, whom shall I send, who will go for us? And Isaiah says, "Hineni, here I am! Send me!"

This has been one of the themes of our time together at OHALAH. It's been mentioned several times -- during the smicha ceremony on Sunday, during Tuesday morning davening, all over the place.

One of the reasons why this is such a resonant theme for us, I think, is that we've all had the experience of saying hineni, here I am -- send me. Send me, God. Send me to share Torah. Send me to bring healing. Send me.

This is in some ways the language of Chabad, the lineage from which Reb Zalman originally came. Chabad speaks in terms of messengers, shlichim, whom they send into the world to spread their particular form of Jewishness.

I don't know that our task is to spread our particular form of Jewishness, per se. (Though I know that I always want to share the things I love best, I know that not everyone in the world wants or needs exactly those things. Besides, Renewal is more an attitude than a set way of doing things.)

But I think we share with our Chabad cousins the existential readiness to be deployed in the service of God, the service of our community, the service of the world. This is something we at this gathering have in common.

We're saying, God, I'm here -- I volunteer for whatever task You have in mind. We're saying, God, I'm here -- send me to care for the community, to tend the world, to build bridges, to heal what's broken.

And I love that. I love being among people who share my yearning to serve. People who share my yearning to connect with God, to connect with Judaism, to open up the riches of our tradition for those who thirst.

This year's OHALAH conference ends today around noon. We'll bid each other (a sometimes emotional) farewell and disperse back into the world until the Brigadoon of our togetherness magically opens up again. Until then -- here we are, God. Send us.

Image: some of the little tents which have been artfully placed around our gathering-spaces, representations of the tents of the 12 tribes of Israel which also suggest to me the big tent which is our organization's logo.

January 14, 2014

Rabbi Sid Schwarz, Where Fools Rush In: Spiritual Leadership for a Changing Jewish Community

This morning I attend a keynote address by Rabbi Sid Schwarz, whom I have known since that PANIM interdenominational rabbinic student retreat I was blessed to attend all those years ago. He's now involved with Clal (the Center for Learning and Leadership, the parent organization of Rabbis Without Borders), and has most recently published Jewish Megatrends: Charting the Course of the American Jewish Future, which makes him a perfect fit for an OHALAH conference themed around He'Atid, the future of Jewish Renewal. His talk is entitled "Where Fools Rush In: Spiritual Leadership for a Changing Jewish Community."

This morning I attend a keynote address by Rabbi Sid Schwarz, whom I have known since that PANIM interdenominational rabbinic student retreat I was blessed to attend all those years ago. He's now involved with Clal (the Center for Learning and Leadership, the parent organization of Rabbis Without Borders), and has most recently published Jewish Megatrends: Charting the Course of the American Jewish Future, which makes him a perfect fit for an OHALAH conference themed around He'Atid, the future of Jewish Renewal. His talk is entitled "Where Fools Rush In: Spiritual Leadership for a Changing Jewish Community."

In a recent presentation to CLI, R' Sid offered a metaphor of broadcast and receiving -- that rabbis need to be able to both broadcast and receive. He suggests to us this morning that we might understand Torah as 70 wavelengths on which we might receive truth. Most of us can only broadcast on a few wavelengths and can receive on fewer than that, and that's something we need to work on.

He reminisces briefly about how he wasn't able to hear Reb Zalman's Torah back in his early rabbinic school days, and indeed regarded it as "strange fire" within the Reconstructionist rabbinical college... and because God has a sense of humor, here he is today, in full awareness of the debt he owes to Reb Zalman and to this neo-Hasidic / Jewish Renewal world. He talks about the shift which unfolded in the 20th century -- thanks to R' Mordechai Kaplan, R' Abraham Joshua Heschel, our own Reb Zalman -- between the vertical metaphor of God (God's up there, we're down here) and a horizontal metaphor of God (we and God are interrelating in an I/Thou fashion.)

I came to understand that what I'd seen as dichotomies in the Jewish world were in fact overlapping truths. We all need to work on our antennas so we can access one more wavelength than before so that we can acknowledge that truth has many faces, as does Torah, at least 70 faces.

He uses his work as a historian to try to help him understand not only the past but also the future. He acknowledges that we read in Talmud (Bava Batra) that from the time of the destruction of the Temple of old, prophecy exists only in the hands of children and fools. But notwithstanding that sugya, we have to try to take the risk of understanding not only the past but how we're going to address the future.

In his newest book Jewish Megatrends he talks about the moment we're at today in American Jewish history: a simultaneous decline of legacy Jewish institutions (synagogues, Federations, JCCs, membership organizations -- the "organized Jewish community") and also a golden age. If you look at the legacy Jewish institutions, the current situation looks like a decline; but if you look at the innovation sector of Jewish life, you see amazing pockets of renaissance.

He files these renaissance happenings under the headings of four pillars. The first is chochmah, wisdom. In 50 years, he suggests, the world will be amazed that religious communities ever though of themselves as independent silos, rather than interconnected. Reb Zalman was way ahead of the curve on this! We all need to understand the overlap between our wisdom traditions and every other. The second pillar is tzedek, justice. And the third and fourth pillars are kehillah (intentional spiritual communities) and kedushah (helping Jews live lives of spiritual purpose.)

He asks: what is the nature of the kehillah we need to create? And what kind of spiritual leadership is required to lead such kehillot?

The American synagogue, he tells us, has gone through three stages, and we now need to figure out how to reach the fourth. First as new immigrants we created little shteiblach, informal home-based communities. As we became better-established in this country, we moved to secondary areas of settlement, creating ethnic synagogues. There might be a modest building, maybe hiring a rabbi with a small salary. In the post-WWII period Jews acquired affluence, moved to suburbia, and in this third era we were living in areas where we were no longer the majority. The synagogues built in that third era were "synagogue centers," which is still the dominant paradigm in congregational life today. And congregations which operate under that paradigm, he says bluntly, are failing. We need to move toward the next stage of the American synagogue.

The synagogue center is failing because it's essentially in a consumer relationship with Jews, marketed like a commodity. Jews decide they need a certain set of goods and services (usually education for their children and of course the bar / bat mitzvah) -- but that b'nei mitzvah tends to be the terminal degree in Jewish life, both in the sense that we won't see most of those families again after b'nei mitzvah is celebrated, and because that in turn suggests the end of the Jewish future. People make decisions based on: what synagogue is convenient to me and offers a fair market price? People join synagogues when their kids are five, and when their youngest child is 14 they exit the synagogue. And during those years, nothing has changed in the life or heart of the neshama of the Jews who are members of that synagogue center.

Today, given the changing economy and the rise of the internet, the goods and services which for a long time Jews joined a synagogue to acquire can now be acquired á la carte, more cheaply, and sometimes at higher quality than via joining a shul. So the primary draw for Jews to join synagogue centers has evaporated.

Here's the good news. Over the past 20 years, some new thinking has emerged about the nature of synagogues. (See Synagogue3K, STAR: Synagogue Transformation And Renewal, etc.) In the early years seminaries were grouchy about this new way of thinking, but today most seminaries are getting clarity around the fact that the kind of rabbis they're training, and the synagogues for which they're training them, will not serve the needs of the American Jewish community of the future.

Synagogues which are stuck in the synagogue center model, he says, are doomed. The best development consultants in the country can't transform those old-model synagogue centers into what's needed now. Change needs to come from rabbis; from inspired spiritual leaders who have a vision of what inspired spiritual community could look like. Beyond that, we need a toolkit for that transformation, because otherwise all of our energy and passion is going to lead us nowhere and we're going to crash and burn in frustration.

Organizations naturally resist change. And in synagogues it's even harder because resistance to change takes on a theological cast. We feel the weight of the challenge of trying to preserve a tradition which we love, as rabbis, but which (practically) nobody else gets. He quotes R' Harold Schulweis: "Rabbis have answers to questions which Jews no longer ask." (A rueful and knowing sigh moves around the room.)

You can broadcast [your teachings] all you want, but if you don't tune in to the wavelength of the Jews you want to touch, your broadcast is useless.

There are, R' Sid says, three barriers in this work. First: the nomenclature problem. Second: a turf problem. And third: a play-it-safe problem.

When he wrote Finding a Spiritual Home, he was writing about people who had a deep desire for spiritual community and hadn't found it anywhere in the organized Jewish community. In the late 90s, it was hard to find four synagogues to profile. Today there are several dozen new-paradigm synagogues! But here's the nomenclature problem: many of them don't want to call themselves "synagogues," because the word is so poisoned. Think of Ikkar in LA; The Kitchen in SF; Mishkan Chicago; Romemu in NY. These places are doing amazing work in this new paradigm model, but they often don't call themselves synagogues.

And, people are using different words to describe the same phenomena: "the synagogue community," "sacred community," "the emergent synagogue," "commanding community," "visionary synagogues," "kehillot." There's so much overlap in the work of creating these kinds of communities -- but if we're going to have a social movement, we need to agree on nomenclature! It sounds like a minor thing, but having common language can make a real difference in terms of galvanizing the people who understand that we can't keep doing what we've been doing in the ways we've been doing it.

The second problem is the turf issue. Three years ago, within a span of 3 months, the Conservative movement came out with their strategic study of their movement and the numbers were dreadful; the Reform movement experienced a revolt in some of the largest synagogues in their movement, and those communities declared intention to bolt; and the Reconstructionist movement sponsored a program on "rethinking the rabbinate." So R' Sid wrote an essay called "Are Synagogues Still Relevant?" which argued that there's idiocy in every movement trying to do the same thing, competing to see who's going to get to the finish line first.

There's a growing body of expertise and best practices among everyone who's trying to solve these problems. If there were ever a time when the denominations should come together and say 'we should work on this collaboratively,' this would be the moment!

(That draws spontaneous applause.) But, he argues, it's not going to happen. The denominations won't want it to happen -- and, he cautions, even we here in this transdenominational gathering are challenged by this work.

Jewish Renewal emerged as a nondenominational phenomenon. But Max Weber and Reinhold Neibuhr draw out the trajectory of all emerging religious movements -- from sects to churches. Sects begin with charismatic leadership, which we here in Renewal clearly have. They have "insider language," which we here in Renewal also have. But ultimately in order to survive, we move from the sect stage to what looks like a much more conventional denomination, and R' Sid sees that hapening here. "I'm not saying 'don't do that,'" he notes. "But before we cast stones at the denominations which have been functioning for a century or more, remember that you too are on a trajectory."

"To say that there are many ways of being Jewish is a narrow ridge to walk, but we must walk it."

And the third problem he cites is a taking-risks problem.

We need to encourage our rabbis to be risk-takers -- to dramatically rethink what synagogues can be and need to be. And we need to educate our lay leadership to be in partnership with us, the spiritual leaders -- we need them to give us space to take risks and to fail! As long as we learn how to "fail forward." Because nothing ventured, nothing gained. If we want to play it safe, we condemn ourselves to stay on the trajectory of synagogues that will continue to shrink.

With awareness of those three obstacles, he moves on to the four pillars of intentional spiritual communities. An intentional spiritual community needs to be mission-driven. Writing a mission statement and then ignoring it -- that's not enough; that's not a living document. We need direction. If you have no destination, any path will do; but if you're clear where you're going, you can correct when you stray from the path.

An intentional spiritual community needs to create an empowered and self-generating culture. Kedusha (holiness), like love, can only be created with reciprocity. It's not a one-directional relationship. To get the gift of Torah, we take upon ourselves the ohl mitzvot, a sense of obligation. "Even if you're agnostic about the idea of Torah from Sinai, you can understand that community itself can be the commanding voice which gives shape to the desire of God." We are all b'nei brit, children of the covenant. We are born into a sense of obligations and we need to make comnunities understand that we are obligated to a higher sense of purpose and also to each other.

The greatest gift we have in Jewish community, which remains untapped in most synagogues, is the brilliance and gifts of the people in front of us. And so often we reduce people to "dues-paying members." We have an obsession with size and membership, which has no meaning whatsoever. We need to move to a commitment to ownership. It's not how many people pay dues -- it's about how many people feel that they are part of a community of Jews who are committed to some sacred purpose.

He moves then to talking about framing serious Judaism. Larry Kushner has a great piece, The Tent-Peg Business, written back in the 70s and still relevant. The way he judges success in his community is how much Jews engage in primary Jewish acts. And he defines those primary acts the way the tradition does: Torah -- avodah / service / some encounter with the divine and with sacred purpose -- and gemilut chasadim, acts of personal lovingkindness and acts of global and social repair.

One of the greatest errors made by non-Orthodox Judaism in the 20th and 21st century is the belief that the only way you get Jews in the tent is by offering "Jewish Lite." The communities which are thriving are those which offer a sense of authentic Jewish encounter with Torah, avodah, and gemilut chasadim.

To be fair, the reason we went down the road of Jewish Lite was that earlier generations wanted to desperately to "be American" that they wanted to fit in, not to stick out like a sore thumb. But that's no longer an issue with the next generation. Now the next generation is asking, "do I need Judaism?" Many of them look at religion and see narrow-mindedness, chauvinism, and fanaticism. If we want to reach that sector of Jews, we need to think of other ways of talking about what sacred community might look like.

He cites the Pew study: that 94% of Jews say they have a positive feeling about being Jewish. This is an amazing thing! People already have a positive feeling about Judaism -- but the way to get them to live out that positive feeling is to give them serious Judaism, Torah and avodah and gemilut chasadim.

The fourth pillar of building intentional spiritual communities is, he says, visionary spiritual leadership. In the mid-20th century as the Jewish community was building synagogues and community centers all over America (proving that we could build shuls as large and beautiful as their churches), rabbis were trained to be CEOs of those synagogues. (And this is something about which Reb Zalman spoke as recently as yesterday at the smicha ceremony -- that it's fine for our boards to want to run synagogues as businesses, as long as they remember that synagogues are in the "business" of doing Jewish, not the business of earning dues.)

The chavurah movement arose in response to this -- the yearning to create rabbi as teacher, friend, colleague instead of the "imperial rabbinate" paradigm. That was a good corrective to the CEO model, but that also doesn't turn out to be all that's needed. We need to own our power as rabbis with sincerity, clarity, integrity, strength. Rabbis need to listen -- but we also need to be able to dip into our well of deep wisdom and to share that wisdom. We need to be able to share what people could aspire to become, and to put that out there, and then listen to their reaction. That, he says, is the recipe for success.

Our tradition, he reminds us, is not value-neutral. Judaism is in favor of certain ways of being in the world. We as teachers and rabbis need to give voice to that as strongly as we can! Jews are hungry for rabbis who can make some sense out of a world that seems to get more materialistic, more superficial, more profane and less compassionate every day. They need our vision of what sacred community can look like. Rabbis can't be CEOs, but neither can we just be facilitators. As important as learning Tanakh and rabbinics and Hasidic texts, he suggests, is taking time to study the works being written around leadership.

We are on the cusp of enormous potential. But we need to tune up our antennas, to listen to the fact that Torah comes in at least seventy faces, and to understand that the Torah we have to offer is a Torah that Jews are hungry for.

January 13, 2014

Remembering Monday morning prayer

My Monday morning at the OHALAH conference began with the most glorious and extraordinary service led by my dear friend Rabbi Chava Bahle. Her service interwove poetry, mikvah meditation, water, song and prayer in a way which created (for me) a deep sense of joy.

My Monday morning at the OHALAH conference began with the most glorious and extraordinary service led by my dear friend Rabbi Chava Bahle. Her service interwove poetry, mikvah meditation, water, song and prayer in a way which created (for me) a deep sense of joy.

We sat in a downstairs room with the curtains pulled wide open. The overhead fluorescent lights weren't on, so as the sun rose, shafts of golden light iluminated the room.

Each us of received a bowl of water, a washcloth, a handout of prayers and poems, and a penny to place in the pushke on our way out so that we might end the service with tzedakah.

We began with a song and with a breathing meditation from Thich Nhat Hanh. The first breath: remembering that I am mortal. The second breath: remembering that those around me are mortal. The third breath: recognizing that our mortality makes this moment incomparably precious.

We learned some Torah together. We engaged in a priestly handwashing meditation. We breathed together, sat in silence together, listened together to Reb Chava reading poems. (Some of the poems came from a book called Go In and In, which I have now ordered for myself, because I want to use some of those poems in my services too!)

Sometimes she asked for volunteers in the room to read quotes from the handout -- quotes from Pirkei Avot, Sfat Emet, various kabbalistic sources. When more than one person spoke up at once, she asked them to read together, in harmony, as one voice.

For me the highlight was the meditative mikveh practice in which Reb Chava led us through dipping our cloths into the water and gently washing different parts of our face and head, in silence, as she offered intentions such as:

I am cleansing my forehead, and all that it represents, so that I may be free from critical and judgemental thoughts, whether they are thoughts about myself or about others, and so that I can direct my thoughts to holiness on this day.

I am cleansing my ears so that I will be able to hear the deeper truths of all that I encounter.

I am cleansing my eyes so that I will be able to see things as they are, to develop deep compassion for life...

(That meditation is adapted from David A. Cooper's The Handbook of Jewish Meditation Practices: A Guide for Entering the Sabbath and Other Days of Your Life and from Rabbi Joseph Gelberman.)

(That meditation is adapted from David A. Cooper's The Handbook of Jewish Meditation Practices: A Guide for Entering the Sabbath and Other Days of Your Life and from Rabbi Joseph Gelberman.)

When we reached the donning-tallit stage of the service, we read aloud a beautiful tallit meditation adapted from Yitzchak Buxbaum, which I loved and want to try to integrate into what I teach b'nei mitzvah kids. It begins:

A tallit represents the world.

Its four corners are the outer reaches of the known,

its fringes an invitation to the unknown.

Continue to tie me to the generations before me who wore tzitzit...

When we sang the shema, after a sweet timeless time of meditation and prayer, our voices rose together in multipart harmony and I felt as though we were all droplets in the same flowing stream of water, unified.

I told Reb Chava at the end of the service that if this were the only thing I experienced that day, dayyenu, it would be enough. And I meant it.

It's a sweet thing to remember today, as I lead my own (much less elaborate) meditation minyan at my small shul, grateful to be home but also looking forward to the next time I get to see my beloved Renewal community again.

January 12, 2014

The Sunday leading up to OHALAH

I always forget how glorious it is to daven with this community. A room full of people, all of us already connected with the liturgy, connected with God, connected with each other. The way weekday nusach interweaves with new melodies and we all just roll with it. Beloved friends' voices all around me, reverberating through me. It is like that first long glass of water after the hot Tisha b'Av fast. I knew I was thirsty, but I didn't remember how good it would feel to have that thirst quenched.

I always forget how glorious it is to daven with this community. A room full of people, all of us already connected with the liturgy, connected with God, connected with each other. The way weekday nusach interweaves with new melodies and we all just roll with it. Beloved friends' voices all around me, reverberating through me. It is like that first long glass of water after the hot Tisha b'Av fast. I knew I was thirsty, but I didn't remember how good it would feel to have that thirst quenched.

A friend tells me that at the beginning of the Shabbaton which preceded the conference, Reb Zalman spoke about the atomic clock in Boulder with which other clocks are calibrated. Coming together here in this way each year, he said, is our recalibration time.

The metaphor gives me shivers. (He is a master of metaphor, our beloved rebbe.) Yes. This is how we recalibrate. How we re-align ourselves with the Source of all things. How we tune ourselves to each others' energies, so that we're all moving according to the same rhythms again. Over the course of the long year when we are apart, we all fall out of step, out of synch, out of attunement with God and with each other. When we return here, our clocks snap back into the groove of shared time.

In the parking lot of the conference hotel I see this license plate. Sh'viti -- the first word of Psalm 16 verse 8, "I keep God before me always." I love that whoever drives this car chose to put this reminder of divine presence in a place they would see every day. I love that for those who speak Hebrew and are driving behind this car, it serves as that reminder of divinity, too. God is in all things -- even a license plate.

In the parking lot of the conference hotel I see this license plate. Sh'viti -- the first word of Psalm 16 verse 8, "I keep God before me always." I love that whoever drives this car chose to put this reminder of divine presence in a place they would see every day. I love that for those who speak Hebrew and are driving behind this car, it serves as that reminder of divinity, too. God is in all things -- even a license plate.

At the conference's opening session, Rabbi Dan Goldblatt tells us a story about his zaide (grandfather)'s sukkah, which was constructed -- literally -- out of doors which no one needed anymore. He reminded us of the teaching about Abraham's tent, open on all sides to all comers. And he compares this conference to that tent, to that sukkah, a place where the doors are open to all.

Our work in the world, he tells us, is to bring Judaism to life. We come here to recharge our batteries so that we can do that work.

Late morning on Sunday: I go down to the room where the musmachot (the soon-to-be-ordained rabbis, cantors, and rabbinic pastor) are sitting behind a long banquet table. In front of each of them is a te'udah, a certificate of ordination; teachers move along the table, signing each certificate and offering blessings.

Late morning on Sunday: I go down to the room where the musmachot (the soon-to-be-ordained rabbis, cantors, and rabbinic pastor) are sitting behind a long banquet table. In front of each of them is a te'udah, a certificate of ordination; teachers move along the table, signing each certificate and offering blessings.

When I arrive there, I find a dear friend who received smicha with me. We are both there to offer a blessing to the same person, and we decide to offer one together, jointly. We laugh about how once upon a time, each of us would have scripted the moment down to the last detail, and now we're both planning to offer a blessing extemporaneously, channeling whatever needs to be said in the moment. "That's how we know we're rabbis now," she quips.

At the end of our blessing, my friend bestows a new kippah on the musmechet. But the comb has come loose, so we dash upstairs, find someone to let us into the shuk where her sewing kit is stashed, and then curl up on big cushy sofas in the lounge to talk while she carefully hand-stitches the comb back in. We talk about rabbinic school and about being rabbis and about the communities we serve and about how sweet it is to see dear friends reach this culmination point.

The smicha ceremony is, as always, extraordinary. I kvell to see dear friends walking beneath the chuppah. I thrill to their divrei Torah and their teachings. And when we reach the recitation of the lineage, I fumble for my tissues, because I know it's going to make me cry, and it does. Every year when Reb Daniel recites the parallel smicha of Miriam, he has to stop to compose himself, and that's when my tears of joy emerge.

It's kind of amazing, watching the smicha now. I used to watch the ordination with a fervent sense of yearning: that might be me, someday. Now it's more like a strengthening of a flame that already burns in my heart. I see my colleagues go beneath the chuppah, I see them leaning back on the hands of their teachers, and I remember again how it felt to have their hands on me, to feel that transmission of blessing, to emerge changed.

It's kind of amazing, watching the smicha now. I used to watch the ordination with a fervent sense of yearning: that might be me, someday. Now it's more like a strengthening of a flame that already burns in my heart. I see my colleagues go beneath the chuppah, I see them leaning back on the hands of their teachers, and I remember again how it felt to have their hands on me, to feel that transmission of blessing, to emerge changed.

Not long ago I was at a christening, and the pastor mentioned that witnessing the baptism of a baby is an opportunity to renew each (Christian) person's own baptismal vows. Being at an ALEPH smicha feels that way for me now -- like an opportunity to renew my connections, to re-open that channel of blessing, to recommit myself to serving God and serving this community.

After the reception, I join a caravan of friends going out for Ethiopian food to celebrate the smicha. I miss the conference's first evening of programming, which I'm sorry about. But spending the evening eating and talking and listening to toasts and niggunim and feeling embedded in beloved community -- that's a gift beyond price. By the end of the day I'm exhausted but grateful, so grateful, to be here and to have this chance to recalibrate -- recharge -- rekindle.

(Photo of Sunday morning davenen: by Janice Rubin, from OHALAH 2013. Other photos: from my flickr stream.)

A poem about the end of Shabbat on the road

SEU'DAH SHLISHIT AT THE ATLANTA AIRPORT

Two thousand miles away

as evening cloaks the rockies

you gather to dine on song

as the angels do.

My holy third meal

will be local beer

and collard greens

at the airport food court.

You sing psalm 23 with fervor.

Even as the Queen prepares to depart

Her presence is so close

you can almost touch.

I wait for my aircraft.

Is this the magic hour

when my redemption

will draw near?

Se'udah shlishit means "the third meal." It's customary to eat three celebratory meals on Shabbat, one on Friday evening, one at Shabbat lunch, and the third late on Shabbat afternoon, and that third one is called se'udah shlishit. The meal is usually quite small; in some communities, it's only a token few bites of food, followed by long singing.

I have two strong memories of se'udah shlishit with my ALEPH community. One happened in January of 2009, the Shabbat when I had miscarried here at OHALAH. I remember sitting in an unlit room (with big windows through which we could see the impending evening) and singing psalm 23 and beginning to mourn my own deep loss. And the other happened in June of that same year, and was incredibly powerful and healing for me. I wrote about it here -- As Shabbat wanes.

It's a time of incredible poignancy. In a way, it's the time when Shabbat is most present and can be most palpably felt -- and in another way, it's the time when Shabbat is beginning to depart. There's also a tradition which says that at Shabbat mincha (afternoon prayer) time, that's when we are closest to moshiach (redemption.)

Yesterday, during the hour when I suspected my hevre (friends) were observing se'udah shlishit in Colorado, I was stuck in an airport, wondering when and how I would make it to Colorado for OHALAH. This poem was the result. It's a bit tongue-in-cheek, of course, but writing it allowed me to feel connected with my community from afar, and I share it here with a smile.

January 10, 2014

Happy news: Ben Yehuda and Open My Lips

I am thoroughly delighted to be able to announce that my next book-length poetry collection, Open My Lips, will be published by Ben Yehuda Press, publishers of books of interest to the American Jewish community since 2005!

I am thoroughly delighted to be able to announce that my next book-length poetry collection, Open My Lips, will be published by Ben Yehuda Press, publishers of books of interest to the American Jewish community since 2005!

Open My Lips is a collection of contemporary Jewish liturgical poetry which I hope will move and delight both Jewish and non-Jewish readers. This collection sits at the intersection of poetry and prayer. Here's my nutshell description:

This volume of contemporary liturgical poetry is both a poetry collection and an aid to devotional prayer. This collection dips into the deep well of Jewish tradition and brings forth renewed and renewing adaptations of, and riffs on, classical Jewish liturgy. Here are poems for weekday and Shabbat, festival seasons (including the Days of Awe and Passover), and psalms of grief and praise. Intended for those who seek a clear, readable, heartfelt point of access into Jewish tradition or into prayer in general.

Ben Yehuda Press has published some wonderful books which are staples of my rabbinic bookshelf, among them Rabbi Shefa Gold's Torah Journeys and In the Fever of Love: an Illumination of the Song of Songs and Rabbi DovBer Pinson's Thirty-Two Gates of Wisdom. (I'm also excited about some of their new books which I haven't yet read, among them Haviva Ner-David's Chanah's Voice, Sharon Marson's More Than Four Questions: Inviting Childrens' Voices to the Seder, and Ora Horn Prouser's Esau's Blessing: How the Bible Embraces Those With Special Needs.) I am thrilled that they are bringing out my new collection.

And -- this is particularly exciting to me as a participant in remix culture and someone who shares a lot of work online -- the publishers are enthusiastic about the poems being available online for people to share during services and poetry readings and so forth. They believe (and I agree!) that sharing poetry online doesn't diminish its sale market, but rather increases it. Our hope is that those who read the poems online, or encounter them during a service, will want to support the poetry and its publisher by buying a copy of the book.

Stay tuned for further information. For now, I hope you'll celebrate with me!

January 9, 2014

When our spiritual sap starts rising

Yesterday when my son and I arrived home after preschool, I could see my shadow against the driveway's thin layer of snow. Night falls early at this season, and the sun had long since set. The shadow came from the half-moon suspended over our rooftop.

Yesterday when my son and I arrived home after preschool, I could see my shadow against the driveway's thin layer of snow. Night falls early at this season, and the sun had long since set. The shadow came from the half-moon suspended over our rooftop.

"Look, mommy -- stars!" We stood there for a moment, our breath drifting up like fog, marveling at the sky. And then I hustled us indoors, because although we're not in the deep freeze of the midwest, the mercury was hovering around zero.

Having a child who likes to look up at the sky helps to keep me attuned to the ebb and flow of the seasons, the waxing and waning of the moon. Of course, so does the Jewish calendar. I wasn't surprised that the moon was half-full already; I know that next week is Tu BiShvat, which always falls at full moon.

The New Year of the Trees. The birthday of the trees. The day when we count trees as a year older than they used to be, even though we no longer tithe their fruits. The day when we believe the sap starts to rise to feed the fertile season to come. Even here, where the ground is rock-solid, impregnated with ice.

If we get days which are warmer than freezing and nights which dip back down into 20s, maple sap really will start rising soon. I always look forward to the year's first maple breakfast at our local sugar shack -- a sign of impending spring even though soft rains and crocuses remain months away. But Tu BiShvat is about more than literal sap creeping up the phloem.

Tu BiShvat is when our spiritual sap starts rising to prepare us for the coming spring. We've been reading the story of the Exodus from Egypt in our cycle of weekly Torah portions; at Tu BiShvat, we take our first step toward Pesach, our celebration of freedom which marks spring's new beginnings. At Tu BiShvat, we assert our trust that our dry and cracked winter souls will be watered and nourished. We open ourselves to feel the abundance which is flowing into our hearts and spirits.

We are the trees, growing older year by year. We give ourselves over to trusting that in the fullness of time, our labors will bear fruit. That we will bring forth nourishment for ourselves and those around us. That this world of winter will end, and be replaced by spring's warm breezes -- and summer's clear sunshine -- and autumn's blaze of red and gold -- again and again, and again.

I make my way to the storage room adjacent to our garage where curls of etrog peel have been steeping in vodka since Sukkot. I decant the liquid, add a simple syrup of sugar-water, and bottle it: etrogcello, made from the pri etz hadar, the "fruits of the goodly tree" (a.k.a. etrogim) which were so central to our celebration of Sukkot. Pri Etz Hadar is also the name of the first haggadah for the Tu BiShvat seder, published in 1728.

When we sip this sweet bright fire at our Tu BiShvat seder next week, we'll swallow a taste of the autumn behind us -- and an anticipation of the autumn which is to come. Sunshine in a jar to nourish our souls, all the way down to the root.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers