Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 166

February 28, 2014

Right here, right now

"Take a moment to settle in to being here," I say aloud. My eyes are closed but I know there are three other people in the room this morning; I heard them walk in, each to their own place in the sanctuary, and I waited until the sounds of their arrival had ceased.

"Take a moment to settle in to being here," I say aloud. My eyes are closed but I know there are three other people in the room this morning; I heard them walk in, each to their own place in the sanctuary, and I waited until the sounds of their arrival had ceased.

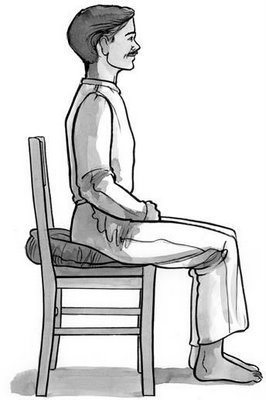

"Notice how you're sitting in your chair. In your own time, draw your attention from your toes up to the top of your head, and if you find places of tension, breathe into them and let the tension go."

"Now we'll move into a practice of following our breath as it comes and goes. When thoughts arise, as they inevitably do -- memories of the past, anticipations of the future -- just notice them, gently, and then let them go."

Like goldfish swimming away, I think.

"If you need something to focus on beyond your breathing, try this mantra. On the inhale: right here. On the exhale: right now. Right here, right now."

Hey, I can write about this, I think. I yank my mind back to right here, right now. Right here, right now.

At the midway point of our meditation, I'm planning to offer a teaching about the practice of teshuvah before new moon -- looking back over the last month and letting go of the places where we missed the mark, at moon-dark, before the new month begins.

Since it's almost new moon. Adar 2 starts right after Shabbat. Adar 2 means Purim. Hey, do all of the Purim spiel actors have their scripts? Okay, that was another stray thought. Letting it go. Right here, right now.

There was a sticker on the door from UPS. I wonder what's in the package? Right here, right now. Inhale, exhale. Maybe it was something for the family trip that's coming up. Right here, right now. The trip isn't happening yet. Stay in the moment.

My ear itches. Right here, right now. The arm where I'm wearing tefillin is getting cold. Right here, right now. Is it time to offer that teaching yet?

The purpose of meditation, it comes to me, is not to still the mind. As though that were possible! I can't quiet my mind. It leaps and races and chatters and changes the subject constantly. The purpose of meditation, at least as I experience it, is to notice the chatter of the mind. To notice all of the thoughts and desires and smokescreens it places in front of me. Not so that I can make them go away, but so that I can be aware of them. That way, when they arise during the day, maybe I'll notice them then, too, and act out of a place of awareness instead of a place of blind reactivity.

Sometimes it feels almost unbearable to sit still and listen to the chatter of my mind. I want to distract myself, to think about happy occasions past or future, to get up and do something: check email, roll the Torah scroll for tomorrow morning's service, tidy my office, anything to give me a break from my own head. But I sit still, and let my thoughts race around me like puppies chasing each other. I cultivate compassion for the antics of my own mind, the lengths to which it will go to avoid just being in the present. Being in the Presence.

Meditation is like Shabbat, I think to myself. Sit still. Stop doing, and just be. This moment is all there is. Right here, right now.

February 27, 2014

Almost done; living in hope

There's a particular energy which comes from the momentum of a big creative project approaching fruition. It's a combination of excitement, anticipation, glee, eager nervousness, hope. Above all, hope. Hope that this prayerbook reaches the people who need it. Hope that I have made something worthwhile, something of use.

I scroll through the draft, admiring the product of countless hours of work. I discover a new image I want to include, dash off an email asking permission to reprint, teeter at the edge of my chair until that permission is granted.

I spend hours learning to use online image-editing software so that I can take apart the cover (designed for a left-to-right book) and reconstitute it for a right-to-left printing. Then I ask an actual graphic designer to do it better.

It's a little bit like anticipating a birth. So many months (or in this case, years) have gone into growing and shaping this creation. Soon it will be born into the world, and people's response to it will be beyond my control.

I go through phases where the project consumes me, and all I want to do is read it and reread it. I proofread again, searching for typos, making sure the internal page references are all correct.

I look back through correspondence and silently thank God again for everyone who agreed to let me include their work for free, because they believe in the project. I hope the project will live up to their expectations.

I try not to imagine the project's reception, or who will use it, or how it might speak to the people who use it -- and of course I fail. All I can think about is seeing this book in someone else's hands, hoping ardently that it is enriching their prayer experience. There's that hope again. It fills my chest as the presence of God filled the mishkan, displacing everything else.

And maybe no one will ever use what I have spent so long shaping. I need to be okay with that, just as when I put a poem (or a collection of poems) out into the world. How can I be okay with that? But becoming okay with that -- that's part of the work, too. This is my offering: to God, to community, to whoever thirsts. And it's almost done.

February 26, 2014

Words for snow

Carved cornices

Carved cornices

perch at

roof's edge.

Plows heap

mountains in

every driveway.

Finger drifts

skitter across

cracked asphalt.

Penitents, thin

snow spikes

reach skyward

marking off

these hills,

feather beds

for giants

drowsing beneath

cold eiderdown.

Warm days:

icicles crash

and shatter.

Sun cups

cradle spindly

tree trunks.

Next storm

always on

its way.

This poem was sparked by that old chestnut about the Inuit having 100 words for snow. Thinking of that led me to researching different English words for snow. I was particularly charmed by cornices (those wind-carved glaciers on rooftops), finger drifts (like tiny snow dust devils), penitents (spikes of hardened snow), and sun cups (the places around trees where the darkness of the bark creates just enough warmth to melt the snow.)

Photo source: my flickr photostream. This was taken last week, before a few days of rain tamped down these fluffy drifts, but the world outside my window is still almost entirely white. Now it's just ice-hard instead of cloud-soft. This may be the shortest month on the calendar, but the wait for March can feel eternal! Of course, March up here means snow, too. But at least it will mean that the snow is on its way toward eventually ending.

February 24, 2014

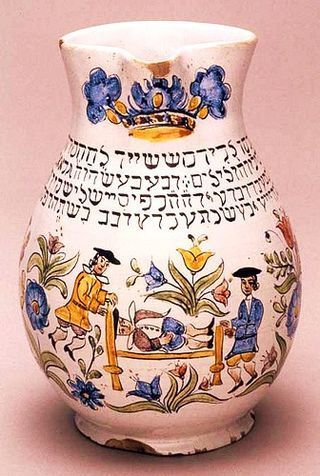

On havdalah

On a recent Saturday at my shul, we paused in an evening program to make havdalah. Afterwards, someone emailed me asking to learn more, pointing out that havdalah was entirely new to them, and perhaps to others as well.

On a recent Saturday at my shul, we paused in an evening program to make havdalah. Afterwards, someone emailed me asking to learn more, pointing out that havdalah was entirely new to them, and perhaps to others as well.

Probably you know we begin Shabbat with a simple ritual: we light candles, bless the fruit of the vine (a symbol of joy and holiness), bless bread (which for most Ashkenazi Jews means challah, though in other parts of the world Jews bless other forms of bread, from tortillas to naan) and in many households also bless our children. Before this ritual, it's still work-week; after the blessings are spoken and the candles are lit, we've entered into the time-apart-from-time which we call Shabbat. Havdalah is the mirror reflection of that; as those blessings began Shabbat, havdalah is how Shabbat ends. The word havdalah means "separation."

At havdalah, we light a braided candle with many wicks, and hold it aloft for all to see. In the most traditional paradigm no fire is kindled during Shabbat, so the striking of the match to light the havdalah candle is a powerful first sign that Shabbat is ending. We bless the fruit of the vine once more. We bless fragrant spices, and pass them around to inhale their heady scent. We bless God who separates one thing from another: separates light from dark, one community from another, the rest day of Shabbat from the six days of work. And then we extinguish the candle in the wine. With that sputter and hiss, Shabbat comes to its end.

After the candle is extinguished, many of us have the custom of singing "Eliahu HaNavi" and/or its twin song "Miriam HaNeviah" -- songs expressing hope for redemption. Then we might sing "Shavua Tov" -- "A good week, a week of peace, may gladness reign and joy increase!" And with that, the new week begins.

I love havdalah. It's one of my favorite rituals in Jewish practice. And it is very much a ritual, not a ceremony. What's the difference? A ceremony, such as a graduation, celebrates and makes official something which has already occurred -- in the case of a graduation, it marks the fact that a student has completed a course of study. (But the course of study is complete already, whether or not the student walks across the stage to receive the diploma.) A ritual, such as havdalah, creates a spiritual change while it is taking place.

I love havdalah because it's the second bookend, the close-parenthesis, which balances the ritual of making Shabbat in the first place. On Friday night we light candles and bless wine; on Saturday night we bless wine and extinguish a candle. On Friday night we begin something special and sacred, and on Saturday night we bring it to its close. On Friday night we open a door, and on Saturday night we close it. We both start and finish Shabbat with mindfulness, taking a few minutes to be aware of a moment in time when something changes. Havdalah is a hinge, a fulcrum-point, balancing between the Shabbat which is ending and the new week which is beginning. We teeter at the top of the hill for a moment and then tumble down the other side.

I love havdalah because it's so poignant. Usually the ritual is done in semi-darkness; we're supposed to be able to see three stars in the sky, so night is really falling. The day of Shabbat is coming to its end. And we gather together, sometimes standing in a circle with our arms around each other, and sing these last songs and gaze at this candle and smell the sweet spices which are meant to revive us from the impending departure of that second Shabbat soul. It feels as though we're coming together to savor the last moments of Shabbat sweetness before they're gone for the week.

I love havdalah because it's so poignant. Usually the ritual is done in semi-darkness; we're supposed to be able to see three stars in the sky, so night is really falling. The day of Shabbat is coming to its end. And we gather together, sometimes standing in a circle with our arms around each other, and sing these last songs and gaze at this candle and smell the sweet spices which are meant to revive us from the impending departure of that second Shabbat soul. It feels as though we're coming together to savor the last moments of Shabbat sweetness before they're gone for the week.

I love havdalah because there are so many beautiful teachings about its additional layers of meaning. For instance: when the braided candle is held aloft, there is a custom of holding up one's hands to see the light illuminating our fingernails and our skin. The Hebrew word for light (אור) and the Hebrew word for skin (עור) are homonyms: they are both pronounced or. When we hold up our hands before the havdalah flame, we remember the teaching (from the Zohar) that in the world to come we will wear skins made out of light, garments woven out of the brightly shining mitzvot we performed in this life.

But most of all I love havdalah because even without all of the extra teachings and interpretations we can lay on top of it, it works. It makes a difference. Spending five minutes in a darkened room holding that braided candle aloft, making these blessings, breathing in the sweet spices, and then plunging the candle into the wine -- it does something. You can feel the change in the energy of the room. Something has ended and something else has begun.

More:

Ending Shabbat: Havdalah - Ritualwell (overview, prayers and resources)

Havdalah: Taking Leave of Shabbat - My Jewish Learning (overview)

Havdalah blessings - Union for Reform Judaism

Debbie Friedman's transformative havdalah melody (includes video) - Jewish Women International

The havdalah category of this blog

Image source for the second image: Astro-Bob.

February 21, 2014

Welcome your extra soul, and irrigate the thirsty world

Our practice of Shabbat restores primordial wholeness to the cosmos. It has the capacity to irrigate the thirsty world. Shabbat is a transformation inside of God in which we are actors.

Our practice of Shabbat restores primordial wholeness to the cosmos. It has the capacity to irrigate the thirsty world. Shabbat is a transformation inside of God in which we are actors.

So teaches Rabbi Marcia Prager, the dean of the ALEPH rabbinic ordination program. (I first shared these teachings here back in 2008.)

Our practice of Shabbat restores wholeness to the cosmos. That is one chutzpahdik assertion. That there is brokenness in the world (in all of the worlds) is beyond doubt. But to suggest that we can repair that brokenness through celebrating Shabbat? Holy wow. And yet this is what our mystics teach: that when we enter into Shabbat wholly, we bring healing to God.

What does it mean to say that "Shabbat is a transformation inside of God in which we are actors"? Perhaps this: God experiences brokenness and separation, because we, God's creation, experience brokenness and separation. But on Shabbat, we create wholeness in ourselves -- and in so doing, we create wholeness inside God. Another way to frame it is through kabbalistic language: when we observe Shabbat, we enable God's transcendence (distant, far-off, high-up, infinite, inconceivable) and God's immanence (embodied, here with us, as near as the beating of our own hearts, relational, accessible) to unite.

And that is why when we experience Shabbat -- celebrate Shabbat, "make" Shabbat, enter into Shabbat -- we open a spigot of blessing to irrigate the thirsty world. Every blessing has the capacity to turn such a spigot, and Shabbat is the blessing of all blessings. Think of all of the sorrow, the distance, the brokenness, the spiritual and emotional thirst in the world. And then recognize that when we open ourselves to Shabbat, and allow Shabbat to work in and through us, we can become channels for the irrigation which would soothe that thirst. It is the active participation of our hearts and souls, experiencing the mitzvah of Shabbat, which unite God far above and God deep within. When that happens, blessing flows.

Some of that blessing flows directly into us. On Shabbat, tradition tells us, each of us receives a neshama yeteirah, an "extra soul." It stays with us until sundown on Saturday, when it returns to God. (This is one explanation for why we breathe fragrant spices during havdalah -- like smelling salts, they're meant to revive us from that soul's departure.) That extra soul is part of who we are, but during the week it's distant. We have two "levels" of soul (actually by some metrics we have four or five, but for now, I'm just talking about two) -- a "lower" soul which enlivens the body, and a "higher" soul which resides with the Mystery we call God. On Shabbat, those two unite. The reality of who we are is joined with the potential of all that we might be.

Some of that blessing flows directly into us. On Shabbat, tradition tells us, each of us receives a neshama yeteirah, an "extra soul." It stays with us until sundown on Saturday, when it returns to God. (This is one explanation for why we breathe fragrant spices during havdalah -- like smelling salts, they're meant to revive us from that soul's departure.) That extra soul is part of who we are, but during the week it's distant. We have two "levels" of soul (actually by some metrics we have four or five, but for now, I'm just talking about two) -- a "lower" soul which enlivens the body, and a "higher" soul which resides with the Mystery we call God. On Shabbat, those two unite. The reality of who we are is joined with the potential of all that we might be.

The Talmud Yerushalmi teaches that Shabbat is equal to all of the other mitzvot put together, and that if just once every Jew in the world truly observed Shabbat together, moshiach would promptly arrive. The teaching raises some questions: what would it mean for all of us to observe Shabbat at the same time? How do we define "us" in a modern, post-triumphalist paradigm? How do we define "observed Shabbat"? For that matter, what would it mean for moshiach to come? But I understand that piece of Talmudic wisdom in this way: if we truly experience the day of Shabbat, we can experience a taste of the messianic era.

Of course, in order for that to happen, we have to make the time to enter into Shabbat. To stop doing and simply be.

We have to be willing to let Shabbat change us.

We have to be paying attention.

Shabbat, and that extra soul, arrive whether or not we notice. But if we can be mindful tonight as sundown falls -- how might the windows of our hearts be opened? With the eyes of that new soul, what might we see?

February 20, 2014

The spiritual work of wrestling with the both/and

I always try to hold on to the both/and. To see things from both sides. To celebrate what is wonderful without ignoring what's problematic: in Torah, in the literary sources I read, in my relationships, in my life. This is one of my central life-values. And I also try to live out this value when it comes to the contemporary Middle East.

I always try to hold on to the both/and. To see things from both sides. To celebrate what is wonderful without ignoring what's problematic: in Torah, in the literary sources I read, in my relationships, in my life. This is one of my central life-values. And I also try to live out this value when it comes to the contemporary Middle East.

"Which Israel?" wrote my friend and teacher Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan earlier this winter [see Which Israel?, On Sophia Street.] "Mediterranean get-away? Holy land? Zionist dream? Occupying power?" My simplest answer to her rhetorical question is: E) All of the Above.

How to describe this place which has such a profound hold on the American Jewish imagination?

The Israel of lofty ideals [see its Declaration of Independence] and beautiful music, of open-air markets and communal farms, where our holy language of prayer is revived on the modern streets, where people live according to Jewish rhythms, gathering to share coffee and dreams for a transformed future?

Or the Israel of violence toward African migrants, imprisonment of refugees [see Detained African asylum seekers in Israel, +972 magazine], occupation [see Reason #12,807 that I hate the occupation, In My Head] and separation barrier and checkpoints?

Or the Israel of violence toward African migrants, imprisonment of refugees [see Detained African asylum seekers in Israel, +972 magazine], occupation [see Reason #12,807 that I hate the occupation, In My Head] and separation barrier and checkpoints?

Most of the public discourse focuses on one of these visions, ignoring (or attempting to discredit) the other.

I'm always feeling at least two things when I think about Israel. This is why I assembled that Complicating Israel Reading List a few years ago. Trying to hold these contradictory truths in my head and heart is never easy, but the alternative -- choosing to view Israel only as good or only as evil -- seems insufficient to me on both intellectual and spiritual levels.

It is tempting for some American Jews, when thinking of Israel, to see only the good. The regal beauty of the Negev desert, Jerusalem's limestone pinked by sunset light, Tel Aviv's cosmopolitan beaches and night life [see Tel Aviv declared world's best gay destination, Ha'aretz]. Extraordinary water-saving agricultural practices [see Kibbutz Lotan]. Glorious new liturgical music [see Nava Tehila]. Pioneering social justice work which aims to protect and uphold the rights of those on the margins. [See NIF: The Social Justice Fund.] For two thousand years our liturgy spoke of the yearning for Jerusalem, and now Hebrew flows once again in those ancient streets -- who could fail to rejoice?

It is tempting for others to see only the bad. The pernicious system of checkpoints [see מחסום Watch] and the system of privilege which allows some people to move freely while others cannot [see Queue Jumping, Bethlehem Blogger], the practice of home demolitions and the separation wall which often divides Palestinian villages, Palestinian children rousted from their beds at night [see Detained: Testimonies from Palestinian Children Imprisoned by Israel, +972 Magazine.]

It is tempting for others to see only the bad. The pernicious system of checkpoints [see מחסום Watch] and the system of privilege which allows some people to move freely while others cannot [see Queue Jumping, Bethlehem Blogger], the practice of home demolitions and the separation wall which often divides Palestinian villages, Palestinian children rousted from their beds at night [see Detained: Testimonies from Palestinian Children Imprisoned by Israel, +972 Magazine.]

Both of these visions of Israel are true. Neither of them contains the whole picture. I believe that a mature relationship with this place requires me to hold these competing truths in balance.

When I am fortunate enough to be able to travel to the Middle East (and when I'm at home, reading blogs and newspapers as widely as I can) I try to stay open to the tension between these truths. I try to remember that the reality is always more nuanced, more beautiful and more painful, more complicated, than any of the easy stories anyone wants to tell.

What this means for me in practice is that I'm always thinking "yes, but..." I read one friend's account of an amazing sojourn of hiking and prayer and community, and I think yes, but don't forget the occupation. I read another friend's account of a harrowing sojourn as a witness to injustice, and I think yes, but don't forget the beauty of the dream fulfilled.

Early in this post I linked to my short essay about loving something while acknowledging what's problematic about it. That can be a difficult tension to maintain, but I think it is among my most valuable spiritual practices. Holding on to my love for something even as I recognize its serious flaws. Not allowing the flaws to erase the love; not allowing the love to cover over the flaws.

Early in this post I linked to my short essay about loving something while acknowledging what's problematic about it. That can be a difficult tension to maintain, but I think it is among my most valuable spiritual practices. Holding on to my love for something even as I recognize its serious flaws. Not allowing the flaws to erase the love; not allowing the love to cover over the flaws.

I'm not interested in the simplistic narratives which make either side (Israel or the Palestinians) into a persecuted innocent or a pariah with no conscience. I'm far more interested in the ideal of "resilient listening," which allows a person and/or a community to live with tension and to hold multiple perspectives at the same time. [See the communication guidelines at Encounter.] This is hard work. It's rarely comfortable. And I think it's vitally important.

I recognize that this is a position of privilege. For those whose children wake crying in the night (in fear of Palestinian rocket attacks and suicide bombings, or in fear of Israeli shelling, arrest, interrogation practices), what I aspire toward may sound impossible or naïve (or both.) I come to this as a Diaspora Jew, from the safe distance (usually) of thousands of miles. And yet, I truly believe that learning to live out this nuanced balancing act matters.

I believe that learning to hold conflicting truths in tension is part of how we grow as spiritual beings. On the Israel front, for most of the people I work with, that means learning to see (and then work toward healing) Israel's flaws and injustices alongside the rosy vision we were reared to cherish. For others, it means learning to see (and then work toward celebrating) Israel's ideals and beauty alongside the mistrust and anger they already carry.

I believe that learning to hold conflicting truths in tension is part of how we grow as spiritual beings. On the Israel front, for most of the people I work with, that means learning to see (and then work toward healing) Israel's flaws and injustices alongside the rosy vision we were reared to cherish. For others, it means learning to see (and then work toward celebrating) Israel's ideals and beauty alongside the mistrust and anger they already carry.

When you love someone, it's easy to see only the best in them. Conversely, when you dislike someone, it's easy to see only the worst in them. I know that it's not easy to choose to complicate one's understanding of Israel in the ways I'm suggesting. (It's also hard for many rabbis to suggest doing so -- see A Third of Rabbis Afraid To Speak Honestly About Israel, The Jewish Week -- or for a more heartfelt and personal take, my Rabbis Without Borders colleague Rabbi Justin Goldstein's The Status Quo Is We Don't Speak About the Status Quo, Sh'ma.) But I think that making our sense of Israel more nuanced and complicated is spiritually worthwhile, no matter what our existing views.

I believe that Israel is beautiful and extraordinary -- and also in ardent need of increased justice and transformation. And: I know that one of my challenges as a rabbi is creating a container which can lovingly hold people who aren't, or aren't yet, able to wholly follow me into this balancing act. To invite those people into the spiritual work of discerning: why am I comfortable seeing this side, but not comfortable acknowledging that side? What is it in me that pushes back against that other perspective? What am I afraid will happen if I allow my perspective to be complicated?

I believe that Israel is beautiful and extraordinary -- and also in ardent need of increased justice and transformation. And: I know that one of my challenges as a rabbi is creating a container which can lovingly hold people who aren't, or aren't yet, able to wholly follow me into this balancing act. To invite those people into the spiritual work of discerning: why am I comfortable seeing this side, but not comfortable acknowledging that side? What is it in me that pushes back against that other perspective? What am I afraid will happen if I allow my perspective to be complicated?

Sometimes saying "it's complicated" can be a way of papering over uncomfortable tensions. [See "Jerusalem is Palestine" and other reasons why I love Israel, The Jerusalem Post.] Saying "it's complicated" isn't an endpoint to the conversation or to the work which needs doing. But (especially for American Jews) I think there's value in moving beyond either/or into the tension of multiple perspectives. Israel is always this and. Beautiful and flawed. Problematic and worthy of love. For many of us, this is a difficult spiritual wrestling match to take on. But that wrestling is the central act for which our patriarch Jacob, and our entire religious community, and for that matter also this nation-state, are named.

All photos are my own: Old City; separation wall; market; sun setting; hospitality; valley of the gazelles. Most links in this post go to my own posts from earlier months and years; links to other websites are so noted, in square brackets.

Comments are welcome, but if you are new to Velveteen Rabbi, please read this blog's comments policy before chiming in. Thanks.

February 19, 2014

On taharah before cremation

Longtime readers may recall that I have been blessed for many years to serve on my community's chevra kadisha (volunteer burial society). We are the group of community members who, before burial, lovingly wash, dress, pray over, and care for the body of each person in our community who dies. Recently I've been pondering a question which is increasingly pressing in my corner of the Jewish community: in the case of someone who chooses cremation, may the work of the chevra kadisha still be performed?

Longtime readers may recall that I have been blessed for many years to serve on my community's chevra kadisha (volunteer burial society). We are the group of community members who, before burial, lovingly wash, dress, pray over, and care for the body of each person in our community who dies. Recently I've been pondering a question which is increasingly pressing in my corner of the Jewish community: in the case of someone who chooses cremation, may the work of the chevra kadisha still be performed?

The simplest traditional answer, of course, is "no." Most halakhists will argue that in the traditional paradigm, Judaism forbids cremation. Therefore, taharah (the washing / dressing / blessing of the body) is not performed when someone chooses cremation, because by choosing cremation that person has implicitly opted out of Jewish tradition. There are dissenting voices arguing that it is not so simple -- Rabbi Gershon Winkler, e.g., writes "It is not so absolutely black and white clear that cremation is forbidden by Jewish law" -- but by and large, most traditional sources regard cremation as forbidden, and in many communities after a cremation the mourners are denied the traditional practices of mourning such as shiva and kaddish.

However, an increasing number of Americans today choose cremation, and Jewish Americans are part of that trend. (See More Jews Opt for Cremation, The Forward.) I have complicated feelings about that choice, because I am attached to the "old ways" of Jewish burial, from the biodegradable wooden aron and linen garments (worn by rich and poor alike) to all of the tactile and embodied experiences of casket and shovel and soil. But what I am most attached to is the gentle care of the chevra kadisha. Is there an argument for retaining that gentle care even in cases of cremation?

My Reform community entered into a discernment process last year around the question of burying "cremains" in our cemetery. I shared excerpts from numerous rabbinic responsa (Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox) as our religious practices and cemetery committees discussed this issue. In the end, my community's decision accords with what seems to be mainstream Reform thinking -- that we strongly encourage traditional burial, but we grant our members the right to make their own informed choices even on this matter. (For two very different Reform perspectives on the issue, see Debatable: Is Cremation An Acceptable Practice for Reform Jews? Reform Judaism magazine.) In our cemetery, there is now a separate section where such remains may be interred.

At the OHALAH conference last month, my colleague Rabbi Efraim Eisen offered a précis of his teshuvah (rabbinic responsum) on the burial of cremains. (See my post Real world halakhic issues in a time of paradigm shift.) He noted that the Babylonian Talmud sees cremation as a denial of the belief in resurrection of the dead, and as such, a denial of the dignity of the body and of God Who created the body. I know that many liberal Jews today do not believe in resurrection, and I wonder: how does that change our relationship with this Talmudic teaching? For instance: for someone who resonates with Jewish teachings about reincarnation, rather than the (generally older) Jewish teachings about resurrection, does that change the sense of what cremation means?

None of this speaks directly to the question about the chevra kadisha. The mainstream perspective largely opposes offering this comfort to those who choose cremation, I suspect because rabbis have not wanted to give even tacit permission to this choice. But it is clear that many people are making this choice, whether we permit it or not. And that, in turn, suggests to me an open opportunity for offering spiritual support and care.

None of this speaks directly to the question about the chevra kadisha. The mainstream perspective largely opposes offering this comfort to those who choose cremation, I suspect because rabbis have not wanted to give even tacit permission to this choice. But it is clear that many people are making this choice, whether we permit it or not. And that, in turn, suggests to me an open opportunity for offering spiritual support and care.

The official stance of the Reform movement is that Reform rabbis should not refuse to preside over the funeral of someone who was cremated. Does it then follow that Reform chevra kadisha members may, or should, be involved in taharah beforehand? This isn't a question in the Reform movement alone. Reconstructionist rabbinic student Joysa Winter writes:

[C]remation does not have to be viewed as "anti-Jewish," but simply as one more adaptation in response to a changing world. Nor do cremation practices, including the scattering of ashes or their burial in unmarked grounds, obviate other Jewish burial traditions. The cycle of mourning practices; the ritual of tahara, or purification of the body, prior to interment or cremation; the graveside service at interment or scattering; all of these can be performed.

(See Jewish Burial in an Age of Ecological Crisis [pdf] in Jewish Currents.)

There are Orthodox thinkers too whose writings suggest a broad perspective on the question of who should receive Jewish burial practices such as taharah. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein permits offering taharah to someone who will be buried among non-Jews, though suggests that in that case the ceremony be somewhat modified; this is not precisely the case at hand, but shows a willingness to expand the boundaries of taharah. And his student Rabbi Moshe Heinemann distinguishes between someone who chooses cremation themselves and someone whose family chooses it for them, and offers taharah for those in the latter category. Both of these open the door for a more inclusive understanding of who merits taharah. (Both of these rulings are cited in the Taharah Manual of Practices, ed. R' Moshe Epstein. Thanks to Rabbi Michael Bernstein for pointing me in this direction.)

We live in an era marked by what Rabbi Irwin Kula has called increased "mixing, blending, bending and switching" of religious practices. An increasing number of Americans feel free to pick and choose among religious practices and interpretations of those practices. It may once have been the case that choosing cremation necessarily implied rejection of Jewish tradition and rejection of the other mitzvot of Jewish burial (taharah among them), but today that isn't necessarily so. Given the value accorded to informed choice in many of today's Judaisms, what once would have been impossible juxtapositions (considering oneself wholly shomer Shabbat while spending the afternoon on Facebook chat, e.g., or a Hebrew school conversation about the appropriate bracha for bacon) are now commonplace. Taharah followed by cremation may today be one of those juxtapositions.

For me, the fundamental principle at work is kavod ha-meit (honoring the dead.) This comes into play in at least two ways: honoring the wishes of the person who has died, and treating their body with honor and care after death. (On the matter of honoring the person's wishes, there's an interesting Conservative teshuvah by Rabbi Morris Shapiro in which he cites the Magen Avraham's point that if someone should leave a will indicating the wish for cremation, that wish should be honored. That teshuvah is online here [pdf]. Also noteworthy: this Reform responsum on the question of a parent requesting cremation, which argues that in the North American Reform movement, cremation is not considered a sin.) While it was once standard Jewish opinion that cremation constituted nivul ha-meit (desecration of the body), it seems clear that many Jews no longer see it as such. Inviting the chevra kadisha to tend to a body before cremation could certainly be understood as a practice of kavod ha-meit.

In the talk by Rabbi Efraim Eisen which I cited before, he noted that there's precedent for halakha conforming to existing cultural practices: "In Brakhot 45a we learn that going out to see what the people are doing is one way to see what the halakha should be." I've had a number of conversations with friends and colleagues who are involved with chevra kadisha work where they live, and I've learned that in many communities, there is a practice of performing taharah on the bodies of those who have chosen cremation. Some suggest one modification to traditional practice, to wit, after the prayers and the washing and dressing and blessing of the meit (the body of the person who has died), the meit is swaddled in a plain white linen or cotton sheet, instead of in tachrichim (the traditional white linen shrouds) and then in such a sheet. Others retain the tachrichim, but modify the prayers and words recited during the process. And still others keep their usual practices entirely intact.

Rabbi Elana Zelony reframed the question for me in an interesting way: just because someone isn't performing one mitzvah (burial in the earth), do we want to therefore take away from them the opportunity to experience another mitzvah (taharah) -- or would we rather seek interpretations which allow us to help the people we serve to embrace as many mitzvot as possible? "My tendency," she writes, "is to encourage people to pursue any mitzvah that interests them, rather than punish them by taking away the opportunity to do a separate mitzvah."

Rabbi Elana Zelony reframed the question for me in an interesting way: just because someone isn't performing one mitzvah (burial in the earth), do we want to therefore take away from them the opportunity to experience another mitzvah (taharah) -- or would we rather seek interpretations which allow us to help the people we serve to embrace as many mitzvot as possible? "My tendency," she writes, "is to encourage people to pursue any mitzvah that interests them, rather than punish them by taking away the opportunity to do a separate mitzvah."

That we are living in a new paradigm, in which old-paradigm practices may need rethinking in order to be both "backwards-compatible" and also living responses to the unique needs of our moment, is a central tenet of Jewish Renewal. It seems to me that one of the characteristics of this moment in time is the increasing porousness of the boundaries our communities maintain around who's "in" and who's "out." Once upon a time, choosing cremation automatically meant that the person was "out." By virtue of making that choice, that person declared themselves to be outside of communal bounds, and therefore it made sense that such a one would not receive the care of the chevra kadisha. But in many liberal Jewish communities today, the choice of cremation no longer carries those same connotations.

Offering a modified taharah to those who choose cremation would root them and their mourners more wholly in our traditions. This practice would also offer spiritual comfort to the mourners (who would have the consolation of knowing that their loved one's body has been lovingly washed and cared-for) -- and to the soul of the person who has died. Jewish tradition holds that the soul of the person who has died lingers with the body for a time, and that the first mourner's kaddish recited at the funeral helps that soul to let go and to move on. (See the Jewish Renewal answer in this Ask the Rabbis: What About Life After Death?) In accordance with that teaching, I believe that the loving practices of taharah help to smooth and soothe a soul's transition from this life into whatever comes next. I can't imagine why that wouldn't be so in the case of someone who was going to be cremated. Indeed: one could make a case that such a person might need this extra love and blessing, this extra help in making that transition, even more than others do.

Perhaps a new prayer should be composed to recite before taharah in cases where cremation has been chosen. That prayer could gently remind the soul that in life it made this choice, and ask for God's gentle care as the soul returns to the Mystery from which it came. Our sages teach (Mishnah Yoma 8:9) that "God is the mikveh of Israel," and that when we seek to immerse ourselves in divine presence (e.g. during Yom Kippur) God's presence purifies us. A prayer for taharah before cremation could assert that as the water we pour cleanses the body, a return to God's enfolding presence purifies the soul, and that that return takes place regardless of what becomes of the body's component molecules.

At the end of Reb Efraim's presentation, he shared something which Reb Zalman said to a chevra kadisha at Temple Adath Or in May 2001. That link will take you to Reb Zalman's whole presentation, but here's the quote which Reb Efraim cited:

I don't want to give you a big green light for cremation. Because a lot of stuff in Judaism says it's a no-no. But some years ago I published something where I said I wanted my remains to be cremated and the ashes to be taken to Auschwitz. My father was born in Oswiecen, my zaide was a shochet there, and when I was half a year old, they took me to zaide so he should bless me. This has become such a terrible place for us...

One of the reasons why they say no to cremation is because of something that it says in the Talmud. Titus, who had desecrated the Temple, wanted to have his corpse burned and his ashes strewn all over so that God wouldn't be able to call him to judgement. In other words, people who go to cremation won't be resurrected. But if God isn't going to resurrect the people who burned at Auschwitz, I don't want to be resurrected either.

I resonate both with Reb Zalman's desire to continue to promote traditional Jewish burial practices, and also with his sense that in a post-Shoah world, it may be necessary to rethink our relationship with cremation. When we affirm that our souls return to that great Mystery which we name God whether the body dissolves via the slow decomposition of earth and water, or via the fire and air which once consumed our offerings on the altar, we sanctify the memories of those who were burned... and we open up new ways of caring for those who choose counter to traditional Jewish burial.

I resonate both with Reb Zalman's desire to continue to promote traditional Jewish burial practices, and also with his sense that in a post-Shoah world, it may be necessary to rethink our relationship with cremation. When we affirm that our souls return to that great Mystery which we name God whether the body dissolves via the slow decomposition of earth and water, or via the fire and air which once consumed our offerings on the altar, we sanctify the memories of those who were burned... and we open up new ways of caring for those who choose counter to traditional Jewish burial.

Inviting the participation of the chevra kadisha before cremation is one way for us to tend to both the living souls of mourners, and the in-transition soul of the person who has died. This practice can coexist with encouragement toward traditional burial in the living soil of our earth. And our openness to these differing paths may open up, for those we serve, the possibility of deeper spiritual engagement with preparation for death; with the journey of death itself; and with the rhythms of mourning after a loved one is gone.

February 16, 2014

Ki Tisa: Shabbat, the Golden Calf, and Rest

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

This week's Torah portion begins with Moshe atop Mount Sinai, communing with God. The last thing God says to Moshe is a set of verses we now know as V'shamru, commanding us to keep Shabbat throughout the ages as a sign of covenant with God. Then God gives Moshe the two tablets, inscribed by God's own hand.

Meanwhile, the people are anxious. Moshe has been gone for a long time. They implore Aaron, his brother, to "make them a god." They donate their gold jewelry, and from that jewelry is fashioned a calf which they begin to worship.

When Moshe comes down the mountain, he shatters the tablets in his fury.

Many commentators have seen this incident as a kind of spiritual "adultery." Here is God reminding us of the Shabbat which serves as the sign of our eternal relationship, and meanwhile we're off giving ourselves over to something which is not God. The Torah frequently compares our relationship with God to a marriage...and here we are, "cheating on" God when the ink on our ketubah is barely dry.

As punishment, Moshe grinds up the calf and makes the people drink it -- which is strikingly similar to the punishment for a woman accused of adultery, as described later in Torah. I'm always struck by the symbolism of making the people confront their own misdeeds in this way. They have to literally swallow what they have done. They have to take ownership of the damage they have done to their relationship with God.

Seen in this light, Moshe's shattering of the tablets is a sign of the spiritual brokenness in that relationship. But what becomes of those broken stones?

We read in Talmud:

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said to his sons: Have care for an old person who has forgotten his/her learning. For we say: Both the whole tablets and the shattered tablets lie in the Ark. (Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 8b)

In the ark of the covenant, which will be kept inside the mishkan / dwelling-place for God, our ancestors carried both the second set of tablets (which are whole) and that first set of tablets (which are broken).

For Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, this holds a message about how to treat our elders. Just as we cherished both sets of tablets, so we should cherish both those who are whole, and those whose wholeness has been broken by sickness or by age.

Perhaps when Moshe broke the tablets, he was demonstrating his own brokenness. His wholeness was broken when his people demonstrated their lack of commitment and faith. Just as our ancestors kept the broken tablets along with the whole ones, we cherish the memory not only of Moshe's beautiful moments, but also his times of imperfection and anger.

Each of us is like Moshe. Each of us carries her own history in the ark of her own heart. In our own holy of holies, we hold our sweetest memories -- and also the times when we have felt shattered. Without both, we wouldn't be who we are.

How does all of this relate to Shabbat and to v'shamru?

The verses of v'shamru, from this week's portion, charge us with keeping Shabbat as an eternal covenant. It is a sign, God says, between us for all time. A reminder that on the seventh day God rested and so do we.

Shabbat is a covenant between us and God. When we keep Shabbat -- whatever that means to us; as liberal Jews we shape our Shabbat observance in accordance with a variety of values -- but when we keep Shabbat, however we keep Shabbat, we re-enact the covenant.

Every week, we renew our wedding vows with the Holy One. We reprise the central act of our relationship, an act of pausing to notice the sacredness of creation.

Every Shabbat is the antidote to the sin of the Golden Calf. Then we were anxious and we put our faith in something gleaming, something we could see and touch. Now we remind ourselves that relationship exists even when we can't see it. That when we make Shabbat, we emulate the ineffable force behind the cosmos in rhythms of creation and rest.

Image source: wikimedia commons.

February 13, 2014

The Purim Without Purim

Tonight at sundown we enter into Purim Katan, "Little Purim."

Tonight at sundown we enter into Purim Katan, "Little Purim."

At the full moon of Adar, we celebrate Purim, our festival of masks and merriment. We read from the Megillah of Esther, we eat hamentaschen and give gift baskets to friends and to the needy, we dress in costumes and make noise to drown out the name of the bad guy who sought to annihilate the Jews of Persia.

Except during leap years. During a leap year, we have two months of Adar, Adar 1 and Adar 2. The "real" Purim comes at the full moon of Adar 2. When we reach the full moon of Adar 1, we get Purim Katan, Little Purim.

What do we do on Little Purim? Well, according to the Mishna, "There is no difference between the fourteenth of the first Adar and the fourteenth of the second Adar save in the matter of reading the Megillah and gifts to the poor." In other words -- it's just like Big Purim, except that we don't read the Megillah or give gift baskets to friends or the poor, which is to say, we don't do the activities which characterize Purim proper at all. Or, as an amnesiac Kermit the Frog put it in an advertising slogan in The Muppets Take Manhattan, "It's just like taking an ocean cruise, only there's no boat and you don't actually go anywhere." I suppose we could still eat hamentaschen.

For those who pay attention to Purim Katan, the usual practice is to eschew fasting, to skip the daily tachanun prayers of repentance, and to avoid opportunities for grief. And some commentators argue that it's a special mitzvah to be joyful on Purim Katan, as a kind of fore-echo of the big Purim a month later.

For me the most interesting thing about Purim Katan is the idea that it's just like Purim Gadol except for all of the outward trimmings of Purim as we know it. That suggests to me that there's a kind of essential experience of Purim which exists somehow independent of the acts which we usually use to cultivate a Purim state of mind.

One of my favorite teachings about Purim holds that our task on this holiday is to ascend the ladder of mystical knowing until we reach God's own vantage point where our human notions of "good" and "evil" disappear. Where Mordechai (the hero) and Haman (the villain) aren't from opposing sides anymore, but are part of a greater whole.

What would it feel like to cultivate such a sense of joy on Purim Katan, such a sense of elevated spirit, that we could seek to ascend to that place even without the megillah and the storytelling, the costumes and the gragers, the cookies and the schnapps?

February 10, 2014

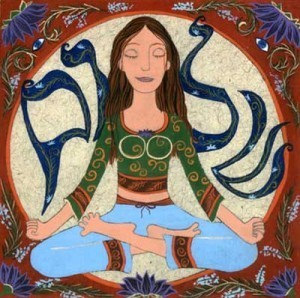

A short history of Jewish meditation

"Would you consider teaching or writing something about Jewish meditation?" a congregant asked me recently. "I think people wonder sometimes whether it's really Jewish."

"Would you consider teaching or writing something about Jewish meditation?" a congregant asked me recently. "I think people wonder sometimes whether it's really Jewish."

Contemplative practice in Judaism has taken a variety of forms, and bears a variety of names, but it's been a part of Judaism for a very long time. ("Contemplative practice" is an umbrella term which covers a variety of practices; meditation is one of those practices.) Let's start here: maybe you know that traditional Jewish practice includes praying three times a day. The traditional explanation for that thrice-daily prayer regimen teaches either that we do this in remembrance of the offerings at the Temple of old, or that we do this in remembrance of the patriarchs (or both.)

We read in Torah that Abraham connected with God in the morning, Isaac in the afternoon, and Jacob in the evening, so we do the same. And in Torah, what form did that connection take? In Genesis 24:63, when Isaac went out לָשׂוּחַ / la'suach in the fields, what exactly was going on? According to the classical JPS translation, that verb means "to meditate." So one could make the case that from the patriarchs on, Jewish prayer has always had a meditative component.

Later, during the time of the Tanna'im (the 1st and 2nd centuries of the Common Era), Jewish mystics sought to elevate their souls by meditating on the chariot visions of Ezekiel. This became a whole school of contemplative practices known as merkavah mysticism. Some of their practices were re-imagined and re-interpreted by later mystical and contemplative movements in Jewish tradition.

Meanwhile, the sages of our tradition were discussing the proper balance of keva (fixed form) and kavanah (intention or meditative focus) in Jewish prayer. Some went so far as to argue that prayer without the right meditative intention doesn't actually count. In the days of the Tanna'im, communal prayer frequently took the form of variations on known themes, where a skilled prayer-leader would improvise new words on the existing themes of the prayers. Over time, those improvised words were written down, and by the Middle Ages became fixed in more-or-less the forms we know today.

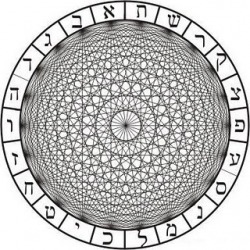

Kabbalah (the branch of the mystical tradition which began around the 11th century) features all kinds of contemplative / meditative practices. These included visualization practices (imagining Hebrew letters and focusing on Divine Names), letter combination practices (mentally combining and recombining Hebrew letters in order to elevate the mind to a higher plane of consciousness), and practices of contemplating different sefirot (aspects or facets of God) -- all of which had the goal, in one way or another, of uniting one's soul with God in a state of devekut, "cleaving" or union. (This was the subject of my undergraduate thesis, so I can go on about it at some length. I'll spare y'all the long version, though if this is interesting to you, let's have coffee sometime!)

Kabbalah (the branch of the mystical tradition which began around the 11th century) features all kinds of contemplative / meditative practices. These included visualization practices (imagining Hebrew letters and focusing on Divine Names), letter combination practices (mentally combining and recombining Hebrew letters in order to elevate the mind to a higher plane of consciousness), and practices of contemplating different sefirot (aspects or facets of God) -- all of which had the goal, in one way or another, of uniting one's soul with God in a state of devekut, "cleaving" or union. (This was the subject of my undergraduate thesis, so I can go on about it at some length. I'll spare y'all the long version, though if this is interesting to you, let's have coffee sometime!)

There's a teaching in the Gemara about the Hasidim rishonim, the first generation of pious Jews, who before sitting down to pray the morning service would first meditate for an hour in order to be able to bring full concentration and intention to reciting the prayers' words -- and after the morning service, would meditate for an hour in order to let the prayers fully percolate into their hearts and souls. Two hours of contemplative practice for every one hour of liturgical prayer: holy wow!

Much later in our history, the movement we now call Hasidism, which began with the Baal Shem Tov in the 18th century, inherited those meditative practices along with the kabbalistic aspiration of seeking devekut with God. A variety of contemplative practices arose in Hasidic communities. One is hitbonenut, "contemplation." In some Hasidic schools this term connotes intellectual contemplation of divinity -- particularly in Chabad, the branch of Hasidism whose name is an acronym for three divine modes of knowing (chochmah, binah, and da'at -- wisdom, understanding, and insight.)

Another form of Hasidic contemplative practice is hitbodedut, which means "self-seclusion" -- for instance, walking alone in the woods and communing with God. This was the practice of the Hasidic master known as Reb Nachman of Bratzlav. He frequently engaged in what we would call "walking meditation," walking alone in nature, while speaking aloud with God along the way. Here's a tiny taste of a prayer attributed to Reb Nachman:

How wonderful it would be if we were worthy of hearing the song of the grass!

Every blade of grass sings a pure song to God, expecting nothing in return.

It is wonderful to hear its song and to worship God in its midst!

(That prayer can be found in A Hidden Light: Stories and Teachings of Early HaBad and Bratzlav Hasidism, by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi and Netanel Miles-Yepez.) This form of contemplative practice tends to be fairly solitary, spontaneous, and unstructured; its goal is to establish a close relationship with God.

In the Mussar (ethical self-improvement) school which developed in 19th-century Europe, contemplative practices were refined and reframed in yet another way. One Mussar meditative practice features focusing on different middot, character-traits or qualities which we can seek to cultivate in ourselves. (These include qualities like patience, lovingkindness, order, humility, and so on.) There are visualization-based Mussar meditative practices, too. Many contemporary Mussar teachers advocate taking time each day to sit in silence and simply notice how one’s mind wanders.

All of this may sound unusual to those of us who are most familiar with the Jewish practice of liturgical prayer, known in Hebrew as tefilah. We may have the notion that meditation is something Buddhists do on their cushions, whereas Jews engage in something different altogether! Except... I'm not so sure it's all that different. I think there's a clue to the meditative quality of Jewish worship in the very word we most frequently use to mean prayer.

All of this may sound unusual to those of us who are most familiar with the Jewish practice of liturgical prayer, known in Hebrew as tefilah. We may have the notion that meditation is something Buddhists do on their cushions, whereas Jews engage in something different altogether! Except... I'm not so sure it's all that different. I think there's a clue to the meditative quality of Jewish worship in the very word we most frequently use to mean prayer.

The Hebrew word tefilah comes from the root l'hitpallel, "to judge oneself." The fact that we use the word tefilah to mean "prayer" hints that our liturgical prayer has at least two purposes. One purpose is to help us connect with God (whatever we understand that term to mean); the other purpose is to take a long deep look inside ourselves, to see who we most truly are, to become aware of our consciousness and our thought processes, and to guide ourselves toward becoming the people we most intend to be. Tefilah is meant to connect us both outwards / upwards / God-wards -- and inwards / downwards / into our deepest selves. Both of those directions can involve contemplative practice.

As I've grown more familiar with our (occasionally wordy) liturgy, I've come to love the idea that even our wordiest liturgical prayer can be understood as a contemplative practice. Of course, in order to be able to experience rapidfire Hebrew prayer as a contemplative practice, one needs to know the words so well that they become transparent and flow from one's lips without effort -- which can be a tall order for most contemporary Jews, for whom the Hebrew may be challenging and the siddur's ancient metaphors distancing. Many of us who are not able to reach meditative states through speedy recitation of Hebrew prayers choose instead to daven shorter versions of the prayers, bringing greater intention and attention to each word.

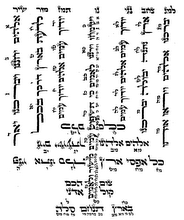

If you've ever seen a page in a prayerbook dedicated to an image made out of Hebrew letters and words -- perhaps an archway, perhaps a menorah, perhaps a tree -- that's another very old Jewish meditative practice. It's called a shviti, after the verse shviti Adonai k'negdi tamid, "I keep God before me always" (Psalm 16:8.) The idea is to gaze at the words which make up the image and to contemplate the words and the letters as a way of keeping God foremost in one's consciousness. (I've written about shvitis before.) Some people carry a shviti with them on a keychain or on a wallet-sized piece of art, in order to be reminded of God's presence every where they go.

Some forms of Jewish contemplative practice borrow concepts and terminology from Western mindfulness practices which may be familiar to other practitioners of meditation -- such as "following the breath," "exhaling the tension from your body," "noticing how the mind wanders." Others are explicitly Jewish in origin and terminology. For example, letter-meditations featuring the four-letter Name of God, where one inhales on the י, exhales on the ה, inhales on the ו, exhales on the second ה. (That's a breathing meditation which allows every pair of breaths to be a recitation of the divine name.) Or the shviti visualization meditation I mentioned a moment ago. There are also embodied Jewish meditation practices which map the sefirot (the diagram of divine qualities, usually conceptualized as a sort of tree) onto the human body and direct energy and attention from one to the next.

Some forms of Jewish contemplative practice borrow concepts and terminology from Western mindfulness practices which may be familiar to other practitioners of meditation -- such as "following the breath," "exhaling the tension from your body," "noticing how the mind wanders." Others are explicitly Jewish in origin and terminology. For example, letter-meditations featuring the four-letter Name of God, where one inhales on the י, exhales on the ה, inhales on the ו, exhales on the second ה. (That's a breathing meditation which allows every pair of breaths to be a recitation of the divine name.) Or the shviti visualization meditation I mentioned a moment ago. There are also embodied Jewish meditation practices which map the sefirot (the diagram of divine qualities, usually conceptualized as a sort of tree) onto the human body and direct energy and attention from one to the next.

At my shul, Jewish contemplative practice takes three different forms. At our Friday morning meditation minyan, we spend half an hour consciously entering into Jewish meditation practices. We follow our breath as it comes and goes, rises and falls; we notice our thoughts as they arise, and without judgement let them drift away; and then depending on the teaching I offer midway through the session, we either engage in guided meditation, or contemplate a quality we wish to cultivate, or reflect on the week now ending in order to process its ups and downs and let it go before Shabbat. That's one way we engage in Jewish contemplative practice.

A few times a year, I lead an explicitly contemplative Shabbat morning service. That's a service which takes the form of chant interspersed with silence. We don't skip any prayers or any of the elements of prayer which are required in order for a person to be yotzei (to have fulfilled the obligation of davening), but instead of reciting each prayer in full-text form, we chant only one or two lines of each, over and over, allowing the meaning of the words to soak in to our hearts and souls. Then we sit in silence for a few moments as the prayer's meaning continues to resonate and reverberate in us before we move on to the next chant. That's a second way we engage in Jewish contemplative practice.

A few times a year, I lead an explicitly contemplative Shabbat morning service. That's a service which takes the form of chant interspersed with silence. We don't skip any prayers or any of the elements of prayer which are required in order for a person to be yotzei (to have fulfilled the obligation of davening), but instead of reciting each prayer in full-text form, we chant only one or two lines of each, over and over, allowing the meaning of the words to soak in to our hearts and souls. Then we sit in silence for a few moments as the prayer's meaning continues to resonate and reverberate in us before we move on to the next chant. That's a second way we engage in Jewish contemplative practice.

And the third form happens frequently during the Shabbat morning services I lead, the "regular" ones which aren't explicitly contemplative. Every time we reach a kaddish, and I remind us that the kaddish is a doorway in the service from one part of the service to the next, and invite us to pause for a moment, and take a deep breath, and see what we're feeling in that moment, and then to carry that feeling (whatever it may be) into the next part of our prayers? That's a Jewish contemplative practice, right there, and that's a third way that we can enter into this ancient tradition.

Jewish contemplative practice can take the form of Torah study, chanting, sitting in meditation (not necessarily in "lotus position" or sitting on meditation cushions -- you can meditate sitting comfortably in a regular chair if that's what works for you), walking in nature, gazing at names of God (on the printed page or in one's imagination), focusing on personal qualities we want to cultivate, reciting the prayers in our siddur with deep intention and attention...and more. Many of these meditative practices are as old as our prayers. And all of them have deep roots in classical Jewish tradition.

If this is interesting to you, don't miss Rabbi Jeff Roth's Jewish Meditation Practices for Everyday Life: Awakening Your Heart, Connecting With God. He's the founder of the Awakened Heart Project, which has as its mission "to promote the use of Jewish contemplative techniques that foster the development of a heart of wisdom and compassion." Rabbi Roth's focus, both in the book and in his organization, is bringing meaningful spiritual practice to life.

For a different perspective, I also recommend Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's Jewish Meditation: A Practical Guide. Rabbi Kaplan is an Orthodox rabbi, and his book explores the deep history of Jewish meditation as well as offering "a guide to a variety of meditative techniques: mantra meditation (with suggested phrases and Bible verses to use as mantras); contemplation; visualization; experiencing nothingness (which he does not recommend for beginners); conversing with God; and prayer." (That's from the Amazon description.)

If you're in or near the Boston area, you might want to check out Nishmat Hayyim (Breath of Life): the Jewish Meditation collaborative based in Boston.

Rabbi Sheila Weinberg, author of Surprisingly Happy: An Atypical Religious Memoir, is also a good resource for Jewish contemplative practices. You can listen to a podcast of some of her teachings here at the Awakened Heart Project. Speaking of which, there's wonderful series of podcasts at the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, by Rabbi Sheila Weinberg and many others, which draw on Jewish contemplative practice(s).

(I welcome suggestions of other resources in comments!)

to promote the use of Jewish contemplative techniques that foster the development of a heart of wisdom and compassion. Cultivating an awakened heart leads to acting in the world with loving-kindness towards all beings recognizing them as manifestations of the Holy One of Being. - See more at: http://www.awakenedheartproject.org/a...

to promote the use of Jewish contemplative techniques that foster the development of a heart of wisdom and compassion. Cultivating an awakened heart leads to acting in the world with loving-kindness towards all beings recognizing them as manifestations of the Holy One of Being. - See more at: http://www.awakenedheartproject.org/a...

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers