Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 167

February 8, 2014

Leah Vincent's Cut Me Loose

I can't remember how I first heard about Leah Vincent's memoir Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After my Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood. I suspect I read an excerpt, probably at Unpious.com, and on the strength of that excerpt pre-ordered the Kindle edition long before publication. (Unpious is the magazine edited by Shulem Deen -- the blogger formerly known as Hasidic Rebel -- which specializes in "voices generally suppressed" in Hasidic and ultra-Orthodox publications. It's worth checking out if you don't know it already.) One way or another, the memoir materialized on my Kindle, so I read it. And holy wow, is this one powerful, painful, and ultimately redemptive story.

I can't remember how I first heard about Leah Vincent's memoir Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After my Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood. I suspect I read an excerpt, probably at Unpious.com, and on the strength of that excerpt pre-ordered the Kindle edition long before publication. (Unpious is the magazine edited by Shulem Deen -- the blogger formerly known as Hasidic Rebel -- which specializes in "voices generally suppressed" in Hasidic and ultra-Orthodox publications. It's worth checking out if you don't know it already.) One way or another, the memoir materialized on my Kindle, so I read it. And holy wow, is this one powerful, painful, and ultimately redemptive story.

Many years ago I reviewed the anonymous YA novel Hush by Eshes Chayil, which told a story of sexual abuse in a Hasidic community. There are ways in which Vincent's memoir reminds me of Hush -- the trajectory from loving and comfortable religious community to ostracism; the unflinching descriptions both of what can be sweet about growing up in a deeply religious community, and also of what can be almost unthinkably bitter. Of course, Hush is fiction while Cut Me Loose is memoir. (Also one is set in a Hasidische community and the other in a Yeshivish community -- though I suspect that distinction won't make much difference to a lot of readers; the two versions of deep Orthodoxy will seem equally foreign.)

Maybe because I came to the book only having read one excerpt, without having read the back jacket copy or any reviews, the book took me frequently by surprise. A trajectory from ultra-Orthodoxy, to going "off the derech," to some kind of new life in the non-ultra-religious world -- that, I expected. But I didn't expect the many mini-journeys along the way: to Britain, to Israel, the rastafarian "boyfriend," the cutting and suicide attempt, each turn off of the prescribed path darker and more painful. Vincent writes about all of this with powerful clarity, and I followed her emotionally into every place her journey went.

This is a tough book to read for me as a passionate liberal religious Jew, especially as a Jewish Renewal rabbi who claims connection through Reb Zalman with Hasidic lineage. I can see in this book some of the things I envy about committed religious community -- families automatically living according to our tradition's rhythms, from choosing a perfect etrog at Sukkot to dancing at Chanukah to turning the house upside-down cleaning for Pesach, experiencing every Shabbat as a time apart from time. But I also see here the things which are most upsetting about insular religious community: control, a rigidity which has no room for personal deviation, and a system which relies upon keeping young women thoroughly uninformed about the outside world (in the name of keeping them "pure") which, when it backfires, can be life-destroying.

It's easy to imagine the ways in which the grass is greener on the other side of that fence -- to fantasize that in a community where everyone cares about Judaism and God as much as I do, it must be easy to keep the rhythms of Jewish life; to live in constant devekut / union with God; to aspire to serve God with joy in all things. This book reminds me that there is a terrible shadow side to that kind of insularity, and that those who deviate from the community's norms -- especially women -- pay an unthinkable cost.

Looking at the book with my Bennington MFA hat on, I relate to it as a gripping memoir. Vincent is a skillful writer with a keen eye for the details which will make a scene pop right off the page. That old writerly adage of "show, don't tell" --? She does that, in spades. Several times, reading this, I thought back on Bennington conversations and panel discussions about memoir, memory, and the complicated ethics of telling one's own story when that story inevitably involves other people who may not wish for it to be told, or for it to be told in the way that feels true to the person writing the memoir.

Looking at the book with my rabbi hat on, I relate to it as though it were a congregant's story, and that makes my heart ache. This book isn't a polemic against ultra-Orthodoxy or against religion. It's just Vincent's own story, and the story speaks for itself. I'm thankful that in the end there is redemption, as well as a community of former compatriots (see Footsteps) who understand both where Vincent is coming from and where she's choosing to be. Still, I come away from the book aswirl with emotions. Wonder, anger, admiration, grief, and above all gratitude that we, her readers, are privileged now to bear witness to the story she so deftly tells.

There's a part of me that wishes I could offer pastoral care to the author of this book. I wish I could sit down with her over coffee or a glass of wine and offer her the listening ear and the loving response which her religious community didn't give. I can't help clinging to the hope that Vincent's sense of herself as a spiritual being, and her connection with God, wasn't thoroughly shattered by the ordeal of her upbringing and its aftermath. That's my own bias as a reader, and I own that. Part of what makes me angriest about Vincent's description of her upbringing is just how badly this religious community mis-served her -- how a family and a spiritual community which should have been a source of nurturing and support became a fountain of rejection, neglect, and emotional abuse.

The author's twitter handle, @EhyehLeah, hints both at God (Who, you may recall, named Herself/Himself/Hirself to Moshe as Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, "I am Becoming Who I Am Becoming") and at the author's own becoming. Maybe that's the best blessing I can offer: celebration of her process of becoming as it unfolds in these pages. May the Source of All Being bring comfort and companionship, self-determination and meaning, joy and gladness in the life she has chosen. And may there be many more books from this strong new literary voice. Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so!

There's an excerpt from the book at JTA: The first step out of an ultra-Orthodox world.

February 7, 2014

The mind is like tofu

Here's the short teaching I offered during our meditation minyan at my shul today. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Here's the short teaching I offered during our meditation minyan at my shul today. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

I learned from my teacher Rabbi Jeff Roth -- who learned from our teacher Reb Zalman (Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi) -- that the mind is like tofu: it takes on the taste of whatever we pickle it in.

What marinade is your mind soaking in today?

Is it a marinade of resentment? She told me she would do that thing, and then she didn't, and now I feel betrayed.

Is it a marinade of anger? On the radio I heard someone from the political party with which I disagree, and now my blood is boiling.

Or is it a marinade of gratitude, of wonder, of readiness to serve in whatever ways the world will call forth today?

We all have recourse to all of these ingredients. Breathe in; and hold it for a moment; and as you exhale, wash the negativity away. Rinse the tofu clean. Once again it becomes plain, ready to take on the flavor of whatever marinade you choose.

As we pray in the morning liturgy: Elohai neshama shenatata bi, tehora hee -- "My God, the soul that You have given me is pure!" Every morning we awake to a clean soul -- a blank slate -- a mind like tofu, ready to take on whatever flavors we steep it in.

Modah ani l'fanecha: I am grateful before You.

Mah norah hamakom hazeh: what a wonder, what a miracle, is this very place, this very moment.

Hineni: Here I am, ready to serve.

Shabbat shalom!

February 5, 2014

On my two rabbinic communities, Rabbis Without Borders and ALEPH

"What does it mean to be a rabbi without borders?" people ask. "Is it like Doctors Without Borders? Do you travel the world?" Not in the sense of accruing more stamps on my passport. The travel is between perspectives and viewpoints, not between nations.

"What does it mean to be a rabbi without borders?" people ask. "Is it like Doctors Without Borders? Do you travel the world?" Not in the sense of accruing more stamps on my passport. The travel is between perspectives and viewpoints, not between nations.

Longtime readers know that I went to a transdenominational rabbinic school where students and faculty from all of the major streams or denominations of Judaism learned together. There are three such seminaries now, though I believe that ALEPH was the first, and ALEPH is unique in its explicitly Jewish Renewal orientation. Anyway: my whole adventure of rabbinic school learning was a transdenominational one. My primary context for rabbinic community has always involved people from different Jewish backgrounds with differing Jewish practices.

For that reason, although I knew I would enjoy the Rabbis Without Borders fellowship, I wasn't sure how groundbreaking or new it would feel to me. After all, sitting around a study table with Jews ranging from Reform to Orthodox was already a familiar part of my worldview, and so was the assumption that there is a multiplicity of valid paths toward truth. So maybe it's not surprising that my experience of RWB/Clal has been in many ways parallel to my experience of ALEPH. It's not so much that the passionate pluralism of RWB feels new, as that it's a delight to discover another transdenominational rabbinic hevre (community of colleagues and friends) who share my ideals and my yearning to bring Judaism and God-connection to those who thirst.

In an ALEPH context, we come together across our differences of interpretation and practice beneath the common umbrella of Jewish Renewal. We share a yearning to revitalize Judaism (or Judaisms), respect for the groundbreaking work of our forebears (among them Reb Zalman), an investment in deep ecumenism, and a unique blend of feminism, progressive values, and neo-Hasidism. In a RWB/Clal setting, the umbrella is klal Yisrael, the Jewish community writ large. Though the qualities which are most central to Jewish Renewal aren't necessarily focal points in RWB, it seems to me that both communities come together across our differences of interpretation and practice to jointly serve the Jewish community in all of its forms, and to bring Jewish wisdom to the wide world. We are, you might say, responding to the same divine call.

In RWB we gather with the utmost respect for each other's perspectives and training. We don't gloss over the places where our practices and comfort zones differ. And we act in the good faith that each of our forms of Judaism is one piece of the Jewish puzzle, one partial truth within the greater truth which belongs to the Jewish community as a whole. For me as a Renewal rabbi, of course, the same metaphor holds true with regard to the religious world -- Judaism has one piece of the truth, Christianity has another piece, and so on, and so on. (I think many RWBs agree on this one, too. Day before yesterday I learned some amazing Hasidic texts with RWB Hanan Schlesinger, who taught -- drawing primarily on the Sfat Emet -- that our real challenge is finding Torah, which is to say finding truth, everywhere. Not only in our own tradition, but everywhere. How beautiful is that?) This is a pluralism which feeds my soul.

And I believe it's a pluralism which the world desperately needs. So much of the news we receive speaks in stark black and white, particularly about religious differences, but reality is far more nuanced and subtle. Truth and meaning aren't the unique purview of any community; as Reb Zalman likes to say, God broadcasts on all channels and each tradition receives revelation based on how we're attuned. I believe that there are glimmers of truth even in worldviews with which I deeply disagree (though sometimes it stretches me mightily to try to find them). And I can seek to open the wellsprings of Jewish wisdom and tradition even for those with whom I have substantial differences. As Rabbi Brad Hirschfield has so eloquently argued, you don't have be wrong for me to be right. I'm more interested in what connects us than in what divides us: across the different branches of Judaism, and across our various politics, and across the varied manifestations of our human family tree.

One of the questions which I think animates this Rabbis Without Borders community is: how can we bring Jewish wisdom to the wide world? What sustenance can we draw forth from our living well which might feed people's hearts and souls in years to come?

In Jewish Renewal we often speak in terms of paradigm shift. When the Temple fell, there was a transition to rabbinic Judaism, which wasn't always easy or comfortable but was utterly necessary in order for Judaism to continue to thrive -- that was a paradigm shift. Reb Zalman has argued that we're experiencing another paradigm shift now, in which we must come to see Judaism, humanity, and our planet in a new way. (The last century's massive destruction, including Hiroshima and the Shoah, is one side of the paradigm shift; seeing our planet from space, that beautiful blue-green ball suspended in blackness, is another piece of the shift. Both of these together call us to co-create new responses to the new challenges at hand.) I believe that the work my Renewal and RWB colleagues are doing, striving to bring Jewish wisdom to the wide world, is part of the tikkun (healing) which this new paradigm shift calls forth.

In Jewish Renewal we often speak in terms of paradigm shift. When the Temple fell, there was a transition to rabbinic Judaism, which wasn't always easy or comfortable but was utterly necessary in order for Judaism to continue to thrive -- that was a paradigm shift. Reb Zalman has argued that we're experiencing another paradigm shift now, in which we must come to see Judaism, humanity, and our planet in a new way. (The last century's massive destruction, including Hiroshima and the Shoah, is one side of the paradigm shift; seeing our planet from space, that beautiful blue-green ball suspended in blackness, is another piece of the shift. Both of these together call us to co-create new responses to the new challenges at hand.) I believe that the work my Renewal and RWB colleagues are doing, striving to bring Jewish wisdom to the wide world, is part of the tikkun (healing) which this new paradigm shift calls forth.

In RWB (and I think also in ALEPH), the borders we cross are those of perspective and practice. We don't all have the same answers. We don't all maintain the same practices. Some of us daven in gender-segregated spaces, and some don't. Some of us maintain deep attachments to the classical halakhic system, and some don't. Some of us are comfortable with substantial liturgical variation, and some aren't. Some of us daven every word in the classical siddur at lightning speed; some of us soak ourselves in slow contemplative liturgical chant. (And some of us do both on alternate days!) We dress this way and that way. We eat this way and that way. But we're united in our belief that we are part of the same enterprise, and that without compromising our ideals or our practices we can work together to bring healing to Judaism and to bring Jewish wisdom to the world.

The fact that I've found not one but two rich spiritual communities of colleagues and teachers who are driven by these passions, who share these commitments to traditional depth and intellectual / spiritual breadth, and who are both willing and able to draw on a variety of different wisdoms (whether within our own tradition, or across many traditions) in order to serve God and to serve the needs of our communities -- it's incredible. I am so blessed.

For more: see RWB FAQ: What is a Rabbi Without Borders? and Kol ALEPH: What is Jewish Renewal?

February 3, 2014

RWB alumni retreat, first 24 hours, in gerunds

Seeing friends from my RWB cohort again.

Seeing friends from my RWB cohort again.

Meeting people from the other rabbinic cohorts.

Putting faces with Twitter handles and email addresses.

At an icebreaker, "outing" myself as a reader of speculative fiction.

(Also as a congregational rabbi and a writer.)

Watching the Superbowl with a room full of rabbis.

Hooting and hollering at the football and the commercials alike.

Sipping whiskey with a friend from far away.

Davening shacharit (morning prayer) b'tzibbur (in community).

Remembering, all in a flash, davening in that same room four years ago.

Meeting people whose work I have long admired.

Hearing from heads of the Republican and Democratic Jewish organizations.

Hearing from heads of the Republican and Democratic Jewish organizations.

Talking, in small groups, about political pluralism and whether / how it's possible.

Chatting about poetry with a fellow-poet rabbinic school friend.

Studying Hasidic texts of passionate pluralism.

Being amazed by their radical welcome and openness.

Studying texts on how blessings turn the forbidden into the permitted.

Tweeting back and forth with RWB fellows who are here, and RWB fellows who aren't here (and tagging it all #rwbclal).

Enjoying dinner conversation about growing up as geeks who love Judaism.

Being with other rabbis who are thoughtful about our rabbinates.

Sitting by the fireside surrounded by quiet conversations and laptops.

Thinking about finding the partial truth in things with which I disagree.

Making midrashic message-driven trash art out of broken cell phones, paint, beads, and clay.

Returning to my room, exhausted from a long day but grateful to be here.

Taking Nyquil and heading for bed.

February 2, 2014

Back at Pearlstone

The last time I was at Pearlstone, I was still a rabbinic student, and I was here for two weeks of ALEPH rabbinic program intensive study. It was my first rabbinic school residency as a mom, and our son was less than a year old -- which meant that first Ethan (for a few days before he went to TED Global and gave the TED talk which led to Rewire), and then my mother, stayed with me and took care of the baby while I was in class.

Then, and now. What a difference 3.5 years makes.

I had some extraordinary experiences here. It was here that I wrote the mother psalm which begins "Don't chew on your mama's tefillin," which to this day is one of my favorite poems in Waiting to Unfold! And it was here that I first got the chance to introduce my mom to my rabbinic school community and vice versa -- a nice prelude to my entire mishpacha attending my rabbinic smicha the following winter.

Last time I came to Pearlstone, we drove down, encumbered by all of the gear required for a two-week trip with a baby: pack-n-play, quilts, stuffed animals, you name it. (And then had to purchase one item we hadn't thought of -- with no bathtub in the room, we resorted to giving baths in an inflatable rubber duckie which Ethan found at a local store.) Last time, I had to ensure that our preferred brand of baby food had the right hechsher to enter the dining hall.

This morning I watched cartoons and played board games with our son, ate a delicious breakfast cooked by my spouse, and then traveled solo to Albany, on my flight, and through the Baltimore airport where I met up with three other Rabbis Without Borders. Together we drove to Pearlstone. And in about half an hour, this year's RWB Alumni Retreat will begin.

I'm looking really forward to a few days of learning, (re)connecting, strengthening friendships, and being lovingly challenged to think outside of my usual boxes. It feels a little bit strange to be here without the loved ones who surrounded me last time I was here. But I'm really excited to see members of my RWB fellows cohort, and to meet rabbis from the previous cohorts who I have until now only known online. I'm really grateful to be part of this hevre (community of friends.)

What we give to make space for God: thoughts on Terumah

Here's the short d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Terumah. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Here's the short d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Terumah. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

This Torah portion contains one of my favorite verses in Torah, a verse I choose to preach on every year: "Let them make Me a sanctuary, that I might dwell within them." We build the sanctuary not so that God can dwell in it -- no matter how beautiful its design or furnishings -- but so God can dwell in us.

And yet, the beautiful design and furnishings seem to be important. Because the Torah spends a lot of time talking about them.

For some weeks to come, we'll continue hearing about the wood and the hammered gold, the supple leathers, the fabrics woven in the most precious of colors, all donated as gifts from those whose hearts so moved them.

What this says to me is: it's important that we give freely, offering up to God things which are precious to us. We're not building the Shekhinah (the indwelling Presence of God) a secondhand home out of scrap. In order to prepare our hearts for that Presence, we have to give something that matters to us.

The children of Israel gave their most precious items freely in order to build a place for the Shekhinah -- in order to open up space for the Shekhinah in their hearts. What would we give, if we were similarly called?

Would we build a home for the Shekhinah out of iPads and Droid phones? Out of expensive clothes and shoes? What would be most meaningful for you to offer? What would make space in your heart for the unfolding of something new?

This morning, each of you is giving ninety minutes of your life to be in community together, to sing and pray together, to try to make a minyan together for those who grieve. Maybe the most precious offering we can give today is our time.

Ninety minutes for Shabbat services. Or half an hour for Torah study. Or five minutes before bed to say the bedtime Shema and look back over the day, to connect with God before sleep. Or fifteen minutes of daily morning prayer -- or of simply sitting and cultivating gratitude for the gifts in your life.

You might wonder, what does God need with these minutes we offer up? But you might as well ask: what does God need with hammered gold and acacia wood? We open our hearts through the practice of giving. When we give, we let God in.

We read this morning about the poles which allowed the Israelites to carry the ark together. We receive the same call: to shoulder the burdens of holy community together. As our spiritual ancestors came together to build and carry the mishkan and the ark of the covenant, so we come together to build and carry our community.

"Let them make Me a sanctuary, that I might dwell within them."

What if we made a mishkan, a dwelling-place for the Shekhinah, out of our attention -- our intention -- our collaboration -- our time? How might holiness dwell within us, then?

February 1, 2014

A poem for Rosh Chodesh Adar א

The first Adar takes its name

from the letter who tells no tales.

Contains "little Purim"

which is just like big Purim

except we don't read the megillah

or send gift baskets

we just cultivate joy.

The first Adar's mitzvot are invisible.

The first Adar conceals its holiness

like a veiled Torah scroll.

It's like the cosmos compressed

into the silent first letter

of the first word

of the first commandment.

Like the queen whose name means hidden,

who keeps her Judaism close to the vest.

Like the Holy One, never mentioned

in our bawdy passion play

but gleaming all over the story

for we who have eyes to see.

Happy Rosh Chodesh / new month!

It's new moon; we've entered into Adar א, the first of this year's two months of Adar. (Why two months of Adar? In seven out of every nineteen years, we get a "leap year," which on the Jewish calendar means we get a whole extra month; that way, our calendar remains in synch both with the cycles of the sun and the cycles of the moon. Adar is the month which gets doubled during leap years.)

Here's a bit more about Adar 1 (2011).

And here's a post about Purim Katan (2011), referenced in the second couplet of this poem.

The final three couplets hint at the Megillah of Esther, the scroll which we read on Purim during Adar ב / Adar 2.

January 31, 2014

Following the breath as it comes and goes

There's something poignant about leading meditation on a morning which will contain a funeral. Following our breath as it comes and goes, knowing that soon we will turn our attention to someone whose breath no longer enlivens.

There's something poignant about leading meditation on a morning which will contain a funeral. Following our breath as it comes and goes, knowing that soon we will turn our attention to someone whose breath no longer enlivens.

In Genesis 2 we read that God formed the first human being out of earth and breathed into its nostrils נִשְׁמַת חַיִּים (nishmat chayyim), the breath of life. In modern parlance the Hebrew נֶשַׁמַה (neshamah) is usually translated as "soul."

Every morning we pray אלהי נשמה שנתת בי טהורה היא (Elohai neshama she-natata bi, tehora hee) -- "My God, the soul which You have placed within me is pure! You created it, you formed it, you breathed it into me, and you will take it from me in a time beyond time..."

My friend Rabbi Arthur Waskow teaches that every breath is a prayer, because with every breath we pronounce the ineffable Name of God.

What is it that enlivens us? It isn't merely breathing, in this age of ventilators which can keep the lungs moving after brain activity has ceased. But without breath, there is no life.

When that enlivening breath is gone, a person's body is no longer that person as we knew them. It remains holy because it once held a soul, but it becomes almost a figurine, a likeness of the person we once knew.

After life, we return our bodies to the adamah, the earth, from which Torah teaches the first earthling was made. The body returns to the earth; the soul-breath returns to the Source from which it came.

I opened and closed this morning's meditation with a practice which I learned from my friend and colleague Rabbi Chava Bahle. The first breath together: a reminder that I am mortal. The second breath together: a reminder that those around me are mortal. The third breath together: a reminder that because of those first two truths, this moment is incomparably precious.

This moment is incomparably precious.

Image source: cauldrons and cupcakes.

January 28, 2014

Finding meaning

At OHALAH, I learn about The December Project, a collaboration between author Sara Davidson and Reb Zalman in which they speak honestly and candidly about aging, death and dying, and the afterlife. I promptly pre-order a copy.

At OHALAH, I learn about The December Project, a collaboration between author Sara Davidson and Reb Zalman in which they speak honestly and candidly about aging, death and dying, and the afterlife. I promptly pre-order a copy.

Upon my return home, a woman seeks me out with burning questions about Jewish beliefs around death and dying, burial practices, the afterlife. We have a long conversation in my office and agree to meet again.

Within days of that meeting, a man seeks me out to talk about illness, end-of-life issues, creating programs to help adult children speak (and listen) clearly to the wishes of their aging parents. We, too, agree to meet again.

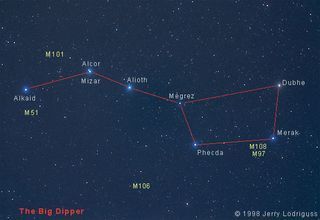

The human mind seeks to make meaning. Give us a handful of stars in the night sky, and our brains sketch them into the shape of a constellation. Give me three disconnected encounters with questions of aging, dying, and what comes after, and my mind wants to turn them into a pattern.

Does it "mean something" that this theme keeps cropping up in my January?

Maybe this is just a reminder that this is a need which people have, these are conversations which people both fear and crave. Maybe it's just a happy coincidence that I learned about a new resource to share, just before I met someone with whom I wanted to share it. These are disconnected events; they have nothing to do with each other.

And maybe the people who brought these questions into my life this month are messengers whose presence is meant to awaken and attune me to these questions. That's what angels are, in the early parts of Torah: messengers sent by God. They look like ordinary people, but they bring awareness of something that someone needs to know or learn.

Both of those can be true at the same time. Anyone I meet can be a messenger if I'm open to finding a deeper message in our encounter. What looks like happenstance to you might look like a holy encounter to me (or: what I experience as happenstance on one day might feel to me like a holy encounter on another day.) Neither of those interpretations has to trump the other.

The stars of the Big Dipper take on a shape because we see the shape in them. So do moments in a life. Connections and coincidences flare brightly because we notice them and draw lines to connect them.

What meaning will I make from the shape which is coalescing here?

January 27, 2014

Two prayers for b'nei mitzvah

Maybe because I'm anticipating (and preparing for) a family celebration of bar mitzvah this spring, I've been on the look-out for poems and prayers for that lifecycle moment. At the OHALAH conference, I picked up a display copy of a new siddur which one of my colleagues had brought to show off. The siddur was Siddur Sha'ar Zahav, a new prayerbook created by Sha'ar Zahav, an LGBTQ Jewish community in San Francisco. And I happened to open it to a page which contained two poems / prayers for b'nei mitzvah, exactly the kind of thing I'd been looking for.

Maybe because I'm anticipating (and preparing for) a family celebration of bar mitzvah this spring, I've been on the look-out for poems and prayers for that lifecycle moment. At the OHALAH conference, I picked up a display copy of a new siddur which one of my colleagues had brought to show off. The siddur was Siddur Sha'ar Zahav, a new prayerbook created by Sha'ar Zahav, an LGBTQ Jewish community in San Francisco. And I happened to open it to a page which contained two poems / prayers for b'nei mitzvah, exactly the kind of thing I'd been looking for.

I liked the readings so much that I got online and ordered myself a copy of the siddur right then and there. And here they are:

To A Bar / Bat Mitzvah

I want to tell you a secret, kid.

Although we say today you are an adult,

because the calendar page has turned,

because your age now has two digits,

because you have studied and prayed

and read and written and worried and hoped

to prepare for this, your big day,

your childhood will continue forever in you,

its questions, fears, wonders, dreams, magic.

Though you take on the stature of adulthood,

its responsibilities, powers, doubts, alleged wisdom,

you will always be a child deep inside,

wandering, seeking, finding, losing, finding, loving.

- Jacqui Shine

Remembering the Bar / Bat Mitzvah Problem

Today I am a man.

Today I am a woman.

Today I am mortified.

Bad enough to be growing into this body, but a public celebration of the fact?

Maybe all b'nei mitzvah struggle with identity, rules, clothes, traditions, expectations.

But can anyone see who I am, hidden by make-up, or by a crew cut and tie?

Years and years later, I can say:

Today I am who I am.

Surely Adonai understands that.

- Ray Bernstein

I suspect that the second reading would speak more to the adults in attendance (who remember the slings and arrows of adolescence, as it were) than to the b'nei mitzvah kid. But it really moves me. And I can imagine parents, or an adult in the family, reading the first one aloud as part of the service, or as part of a toast at the kiddush afterwards, or something along those lines.

If (like me) you collect siddurim, this one is really worth owning. It's a beautiful object, a beautiful book, satisfying to hold. It's well-designed and very readable. It treads a nice balance between traditional and innovative. And in addition to fine renderings of all of the prayers one would expect from any good siddur, it also contains prayers and liturgies which aren't in the average Jewish prayerbook -- blessings for discovering one's sexual orientation, prayers for Transgender Day of Remembrance, and so on. The book isn't cheap, but it's well worth the price. I know I'll be turning and returning to it often.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers