Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 168

January 26, 2014

A small stone for Sunday morning

Chickadees jostle for space at the feeder. The coffeepot murmurs its finishing song. Steam rises from the oatmeal bowl, inscribing unfamiliar alphabets on the air.

For Seon Joon.

January 24, 2014

New essay about motherhood and spiritual life in the Huffington Post

Everyone says that motherhood changes you. That you see things differently once you become a mom. You relate to your own parents differently. You understand things differently. That made sense to me; I expected motherhood to change my outlook. But I didn't expect it to change my brain chemistry -- or my sense of God.

That's the beginning of a new essay (interwoven with bits of poetry from Waiting to Unfold) which appeared this week in the Huffington Post. (It wound up in the Religion section; I wasn't sure whether it belonged in Religion or in Parents! Story of my current life, really.)

Here's another glimpse, from later in the piece:

Elizabeth Stone famously wrote that "Making the decision to have a child... is to decide forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body." Not only because I wish I could protect my own child from sorrow and pain, but because I wish I could protect everyone's children. And I can't.

For a congregational rabbi, this sharp and impossible yearning seems at first blush not necessarily helpful. This doesn't help me hold it together when I'm preparing for a funeral -- or when I'm getting ready for Hebrew school. But in my first year of rabbinic school, when I learned hospital chaplaincy for nine months, one of my older colleagues told me that becoming a parent someday would be the greatest theological education I would ever know. I think this yearning is part of what he was talking about...

I hope you'll click through the read the whole thing: How Motherhood Gives Me A Glimpse of the Tender Heart of God.

January 23, 2014

Phoebe North's Starglass

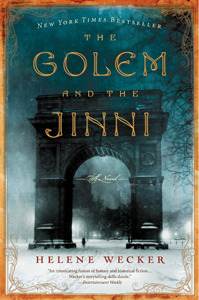

I posted last week about Helene Wecker's The Golem and the Jinni, which I had the opportunity to finish on my way home from the OHALAH conference of Jewish Renewal clergy.

I posted last week about Helene Wecker's The Golem and the Jinni, which I had the opportunity to finish on my way home from the OHALAH conference of Jewish Renewal clergy.

The other book I read on my way home was Phoebe North's YA novel Starglass. It's about a girl named Terra growing up on a spaceship which has been traveling for 500 years toward a new home, a planet the would-be colonists call Zehava, a name which means something like "Golden." (If that puts you in mind of historical Jewish yearning for Yerushalayim shel zahav, Jerusalem, city of gold, you're not far off the mark.)

The premise -- ship full of travelers who departed Earth in crisis and are seeking a new home -- is one I've seen before, and probably you have too. (I think especially of Molly Gloss's gorgeous The Dazzle of Day, one of my favorite examples of that trope.) Part of what makes Starglass unique is how Judaism is woven into the fabric of shipboard life. Well: a kind of Judaism. A Judaism which has evolved in complicated ways over the 500+ years since the asteroid wiped out life on Earth and these colonists set out on their long journey.

The worldbuilding is terrific. (There's a whole page on the author's website dedicated to explaining the world, the ship's architecture, and so on -- but you don't need to read any of that before you dive into the novel; it's just fun stuff to explore once the pleasure of the novel is over.) North trusts us to follow her narration and to understand Terra's world by watching her grow up in it. North doesn't overexplain, and as a result, I as a reader got all kinds of happy little glimmers of recognition as I figured things out.

As the book unfolds, it becomes clear that this isn't just an ordinary coming-of-age story -- not even an ordinary coming-of-age story in space. This is a book about history, totalitarianism, politics, liberty, the importance of fighting for what you believe in. And, of course, also about choice and romance and growing up and parenthood and childhood and all of that good jazz.

For me, the glimpses of how Judaism has been both preserved and mutated are the most fascinating part. The passengers' lingo is peppered with Yiddish and Hebrew words, most of which retain the meanings I know -- but some have shifted. For instance: bar mitzvah, in this book, refers to the coming-of-age ceremony whereby a shipboard boy gets his vasectomy so that accidental pregnancies won't disrupt the delicate ecosystem of shipboard life. (Babies are grown in uterine replicators anyway.) All kinds of substantive Jewish ideas and concepts have been subtly refigured here: mitzvah, tikkun olam... It's both beautiful and chilling to see how Jewish language and practice has shifted in this fictional universe.

There's an excerpt online at Tor.com -- take a peek and see if this book might be your cup of tea, as it was mine. My only real quibble was where it ended; I felt as though we were on the cusp of a whole new adventure, and while it was a reasonable ending-point for the novel, I still wanted more. Then I found out there's a second book coming out next summer, Starbreak. Now I can't wait for July when I get to find out what happens to Terra next.

January 22, 2014

How Shabbat is like a snowstorm

This morning I met again with my usual cohort of Jewish clergy who study sacred texts together each week in the coffee shop. This week, one of our conversations about Heschel's Heavenly Torah went in a direction I didn't expect. We were talking about a passage which contrasts two different ways of approaching Shabbat. In one paradigm (which Heschel links with Rabbi Akiva's school), Shabbat is envisioned as the bride of Israel, our holy mate with whom we experience a supernal connection. In the other (which Heschel connects to Rabbi Ishmael and his disciples), Shabbat is compared to a wolf who causes disturbance both before and after his arrival. The Akivan image of Shabbat as our bride was familiar to all of us, but when it came to the Ishmaelian simile, we kind of scratched our heads: Shabbat, a wolf? What an odd comparison!

This morning I met again with my usual cohort of Jewish clergy who study sacred texts together each week in the coffee shop. This week, one of our conversations about Heschel's Heavenly Torah went in a direction I didn't expect. We were talking about a passage which contrasts two different ways of approaching Shabbat. In one paradigm (which Heschel links with Rabbi Akiva's school), Shabbat is envisioned as the bride of Israel, our holy mate with whom we experience a supernal connection. In the other (which Heschel connects to Rabbi Ishmael and his disciples), Shabbat is compared to a wolf who causes disturbance both before and after his arrival. The Akivan image of Shabbat as our bride was familiar to all of us, but when it came to the Ishmaelian simile, we kind of scratched our heads: Shabbat, a wolf? What an odd comparison!

And then my friend and colleague Rabbi David Weiner shifted the metaphor in a way that made it clear. Shabbat, he said, is like a winter storm.

Before a storm, we scurry around procuring things we'll need -- batteries, flashlights, water, food, what-have-you. We're consumed with anticipation. We batten down the hatches and get ready. And then the storm arrives, and suddenly there's nothing we can do. We stay home. We relax. We have family time. Maybe we play in the snow with our kids. Maybe we read books. Maybe we sit by the fire. Maybe we make time to daven or learn some Torah. All of our usual making and doing and planning is suspended during the time-out-of-time which is the duration of the storm. And then the storm ends, and afterwards we scurry around again, shoveling our walkways, digging out our cars, preparing to dive back into ordinary life.

Just so, Shabbat. Before Shabbat, we scurry around getting everything ready: the challah, the candles, the juice or wine, the festive meal. All of the weekday and workday to-do items have to be completed before sundown on Friday, because once the sun goes down, we enter into holy time. We stop making and doing and focus instead on just be-ing. We have family time. Maybe we play in the snow with our kids, read books, sit by the fire. Ideally, of course, we daven and learn some Torah -- in community, if circumstances permit. Shabbat, like the snowstorm, gives us permission to set aside the to-do list and to just be for a while. And then Shabbat ends and we scurry around again, thinking about work again, preparing to dive back into ordinary life.

Just so, Shabbat. Before Shabbat, we scurry around getting everything ready: the challah, the candles, the juice or wine, the festive meal. All of the weekday and workday to-do items have to be completed before sundown on Friday, because once the sun goes down, we enter into holy time. We stop making and doing and focus instead on just be-ing. We have family time. Maybe we play in the snow with our kids, read books, sit by the fire. Ideally, of course, we daven and learn some Torah -- in community, if circumstances permit. Shabbat, like the snowstorm, gives us permission to set aside the to-do list and to just be for a while. And then Shabbat ends and we scurry around again, thinking about work again, preparing to dive back into ordinary life.

Both a snowstorm and Shabbat offer a break from ordinary workday realities. A time to cease the mechanisms of production and to relax, secure in the knowledge that there's nothing we're supposed to be doing, so we can just be for a change. Of course, snowstorms come and go according to weather patterns most of us don't understand; Shabbat comes every seventh day without fail, if we are awake and alert enough to notice and experience her visit. (Also snowstorms can be dangerous, which is where the comparison breaks down a bit -- I can't really think of any way that Shabbat might pose a danger to anyone.)

It was hard for me to understand Shabbat being like the wolf who causes a stir both before and after his arrival, but Shabbat being like the winter snowstorm which forces us to slow down, stop working, enjoy family time -- that's a metaphor which immediately resonates for me.

For all who are experiencing major winter weather this week, may your snowbound time be safe and comfortable and as restorative as a midweek dip into Shabbat. And for all of us, no matter where we are, may the coming Shabbat bring us the relaxation, surrender, and whimsy which at our best we're capable of finding when the world around us slows down because of snow.

January 20, 2014

Dr. King, z"l (may his memory be a blessing)

I want to say something to honor Martin Luther King Day, but I don't know that I have words meaningful enough for the occasion. And as a white woman, I don't want to co-opt the memory of a great African American leader.

But one of my rabbinic and civil rights heroes, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, was a friend and admirer of Dr. King's. So I'll share a brief quotation from him, speaking after Dr. King's assassination. He said:

Martin Luther King is a sign that God has not forsaken the United States of America. God has sent him to us...his mission is sacred...I call upon every Jew to hearken to his voice, to share his vision, to follow in his way. The whole future of America will depend upon the influence of Dr. King.

(I found that in the essay Two Prophets, One Soul, written by Rabbi Harold Schulweis in honor of Rabbi Heschel's yarzheit.)

We have a long way to go before we reach the America of Dr. King's yearnings. But -- as the sages in Pirkei Avot remind us -- though it's not incumbent on us to finish the task, neither are we free to refrain from beginning it.

I'll leave you with a two-minute excerpt from the film Praying With My Legs, which speaks to how these two great men informed and inspired one another. May we, their descendants, do the same.

May the memory of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King be a blessing.

January 19, 2014

Videopoem!

May I kvell? This is so neat.

Writer and filmmaker Othniel Smith has created a videopoem based on one of my poems -- combining public domain footage, Peg Duthie's audio recording, and my words ("Ethics of the Mothers," which appears in April Daily.) I put the poem in The Poetry Storehouse, but I hadn't actually expected anyone to do anything with it. But Peg and Othniel did!

Thank you, Peg and Othniel!

Tu BiShvat and self-care: a mini-d'var-Torah for Yitro

Here's the very tiny d'var Torah I offered during Shabbat morning services at my shul yesterday. (I kept it brief because I wanted plenty of spacious time for our Tu BiShvat seder after services!) (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

In today's parsha, Yitro, Moses receives some of the best self-care advice in the Torah: you can't do it all yourself. You will wear yourself out, and then you won't be able to help those whom you serve.

We've all been where Moses was: overworked and stretched too thin.

Self-care matters. If we don't nourish ourselves, then we can't do the work we're here to do in the world. Whether you think of that work as "caring for your family and community," or "saving the planet," or "serving God" -- we all have work we're meant to do in this life, and if we don't take care of ourselves, we can't do that work.

Today at CBI we're celebrating Tu BiShvat, the day when -- our tradition teaches -- the sap rises in the trees for the year to come, nourishing the trees so that in the future they can bear fruit.

We too need to be nourished so that we can bear fruit as the year unfolds. As the trees need rain and snowmelt, we need the living waters of Torah to enliven our souls.

As the trees need fertile soil and good nutrients, so we need to feel ourselves to be firmly planted -- and to get all of the physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual nutrients we need in order to grow and to flower.

What nourishment do you most need on this Shabbat?

What would feed you in all four worlds -- your body, your heart, your mind, your soul?

What do you need to soak up in order to be able to bring forth the wonders, the ideas, the teachings, the kindnesses, the mitzvot which only you can do?

And how can you take care of yourself, as Yitro instructed Moshe, so that you will be able to open your heart and receive what you need?

January 18, 2014

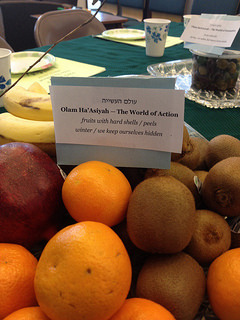

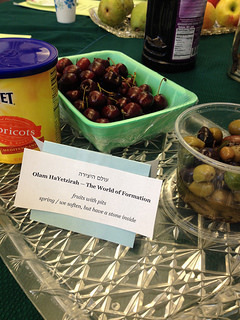

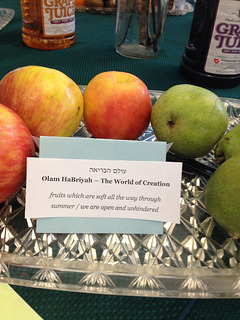

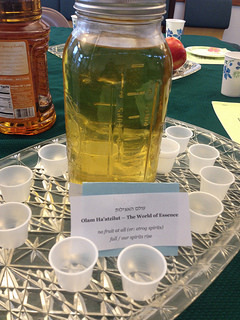

Tu BiShvat in images

Fruits with peels / shells, representing assiyah / action; fruits with pits, representing yetzirah / emotion;

Fruits edible throughout, representing briyah / thought; etrogcello, representing atzilut / spirit.

After services and our (slightly belated) Tu BiShvat seder: the trees sleep beneath their light coat of Shvat snow.

January 16, 2014

The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker

When I started this blog in 2003, it never occurred to me that I might wind up with a sideline in recommending religion-related speculative fiction. But here I am, having written about Saladin Ahmed's delightful Throne of the Crescent Moon last month, and G. Willow Wilson's delightful Alif the Unseen some time before that, and now I've got another recommendation -- Helene Wecker's The Golem and the Jinni.

When I started this blog in 2003, it never occurred to me that I might wind up with a sideline in recommending religion-related speculative fiction. But here I am, having written about Saladin Ahmed's delightful Throne of the Crescent Moon last month, and G. Willow Wilson's delightful Alif the Unseen some time before that, and now I've got another recommendation -- Helene Wecker's The Golem and the Jinni.

This book interweaves two mythologies into one entrancing novel. This is the story of Chava, a golem (think: creature made of earth, brought to life via mystical kabbalistic incantations, á la Rabbi Loew of medieval Prague) and Ahmed, a jinni (think: fire-spirit as mentioned in the Qur'an, the sort once enslaved by Suleyman a.k.a. Solomon) who meet in New York at the turn of the 20th century.

I've known the golem stories for as long as I can remember. I have a tiny clay golem figurine which I bought from a street vendor in Prague (my mother's birthplace) on my first trip there in 1993, and when I wrote my undergraduate thesis on the mystical letter-combination practices of the Sefer Yetzirah and Abraham Abulafia, I spent some time dipping into golem stories just for fun. The jinni material was less known to me, but the book is so deftly-woven that my relatively shallow familiarity with that story didn't matter.

Wecker's depiction of 1899 New York is rich and detailed. Equally so are the depictions of Konin in the late 1800s, and the Bedouin encampment a millennium before. But I think what I like best about the book is the slow, cautious friendship which develops between the two supernatural beings. Both the golem and the jinni are lost in almost-20th-century New York, and as each of them struggles to process the peculiarities of this place and time, the reader experiences the unfamiliar landscape along with them. For both Chava and Ahmed, being exposed to ordinary human society would have disastrous repercussions.

Those similarities aside, they're about as different as two characters can be. One's from Jewish folklore and the other's from Arabic folklore. One's newly-made and the other is ancient as the sands. For that matter, one's (literally) an earth elemental and the other's quintessentially fire, with all of the personal characteristics which those terms imply: steadiness versus capriciousness, rootedness versus wanderlust, quiet contentment versus burning passion. Their relationship is by turns sweet and prickly, filled with misunderstandings -- but as they come to know each other, we get to listen in, and that's a real delight.

There's an excerpt on the author's website. Take a peek, see if this might be a good fit for you. I envy all of y'all who haven't yet read it, and will get to enjoy its twists and turns for the first time.

New essay in Zeek: on Tu BiShvat, parenthood, climate change

It’s fun to teach a 4-year-old about Tu B’Shvat. We’ll probably sing happy birthday to the trees in the backyard, and bless and eat a variety of tree fruits and nuts at a kiddie Tu B’Shvat seder at the synagogue. Maybe we’ll try to connect trees with taking care of the earth, the way Kai-Lan cleans up garbage in the back yard for the sake of the snails.

For adults, Tu B’Shvat offers opportunities for more meaningful reflection.

Tu B’Shvat reminds us to go outside and encounter the natural world where we are. Here in the Diaspora, Tu B’Shvat posters and food traditions remind us of the foodways of our Mediterranean ancestors, including Israel’s blooming almond trees. Where I live, Tu B’Shvat usually means bare trees rising out of snow.

Usually Tu B’Shvat falls during sugaring season in western Massachusetts. The maple sap rises when the days are above freezing and the nights are still cold. All around my region, plastic tubing sprouts like new growth, funneling sap drop by drop into collection buckets and tanks for boiling.

Well: that’s what usually happens. I don’t know how this year’s fifty-degree temperature fluctuations and arctic blasts will impact the syrup harvest. Does that kind of oscillation confuse the maple trees? How about the fifty-below-zero temperatures they’ve been registering in the heartland: how does that impact the food we grow?

That's a taste of Tu BiShvat Reflections on Parenthood, Extreme Weather, & the Human Family Tree, my latest essay for Zeek magazine. I hope you'll click through to read the whole thing.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers