Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 165

March 14, 2014

Video conversation about this week's Torah portion

I had the recent pleasure of participating in a video interview with Shmuel Rosner, the man behind the section of the Jewish Journal called Rosner's Domain. The interview is part of his weekly Torah talk series.

Shmuel has hosted several of my friends and colleagues in this interview series, among them fellow Rabbi Without Borders alumni Rabbi Jason Miller, Rabbi Josh Yuter, and Rabbi Rachel Ain, as well as Rabbis Rick Jacobs, Sharon Brous, and Eliot Dorff. I'm honored to be in this fine company!

We spoke for 8-10 minutes about this week's Torah portion, parashat Tzav; I shared this week's Torah poem from 7o faces; and we talked about Hasidic interpretations of sacrifices, the anointing / ordination of Aaron and his sons, and more.

The video is now live, and you can watch it here:

If you'd like to leave a comment, feel free to do so here at Velveteen Rabbi, or to go to Rosner's Domain where the piece originates: Rosner's Torah-Talk: Parashat Tzav With Rabbi Rachel Barenblat. Enjoy!

March 13, 2014

Recent reprints

My thanks go to the editors at the Reform Judaism blog for reprinting my post Why I love havdalah. I serve a Reform shul and I'm delighted to have that post circulating to the broad Reform community.

And my thanks also go to the editors at Kol ALEPH, the voice of the Alliance for Jewish Renewal, for reprinting my post What was the ALEPH rabbinic program like? (retitled as An ALEPH rabbi reflects on the journey.) I'm delighted to have that post circulating in the broad Jewish Renewal community too.

(And hey, if more Reform readers click through to Kol ALEPH and more Jewish Renewal readers click through to the Reform Judaism blog, that's lovely too!)

Shabbat shalom to all, and chag Purim sameach -- a happy and joyful Purim starting on Saturday night.

What was the ALEPH rabbinic program like?

People ask me sometimes what rabbinic school was like. My short answer is "amazing -- really hard -- and one of the best things I've ever done." But maybe a longer answer would be interesting to those who read this blog.

Disclaimer: this may not be characteristic of everyone's experience; I was a rabbinic student, so I can't speak to the experience of students in ALEPH's other programs; and of course the program continues to evolve, so students today may have some different experiences than I had. That said...

The ALEPH rabbinic ordination program is low-residency, which means that students and faculty live all over the world and come together a few times a year for intensive "residency" periods. In between those in-person gatherings, we learned together in other ways. (When I first started the program, half of my classes were held via conference call; by the time I finished, we were using videoconferencing instead.) Years before coming to rabbinic school I got an MFA in writing and literature at Bennington, and that's a low-residency program too, as many creative writing MFA programs are. It was great preparation for the ALEPH learning experience.

Each ALEPH student works with a Director of Studies (a member of the ALEPH ordination programs va'ad) to establish a committee of mentors who will help her or him navigate the program's requirements.

A minimum of sixty graduate-level classes is required in order to be a candidate for rabbinic smicha, and when I was a student, ALEPH offered about 60% of those classes. For the other classes I needed, I pursued learning at other institutions; entered into small-group learning with ALEPH-approved teachers (I have fond memories of translating and interpreting the Me'or Eynayim with two friends and with Rabbi Bob Freedman); and also often engaged in structured one-on-one tutorial learning with a local rabbi friend (once that learning had been approved by my Director of Studies -- which generally required a syllabus and at least one major paper.) Most semesters, I took two ALEPH classes and two classes elsewhere, or three ALEPH classes and one elsewhere. But the majority of my learning was done in an ALEPH context.

It's also worth mentioning that the 60-course minimum is just that -- a minimum. Often the va'ad imposes additional requirements tailored to the learning trajectory of the student. (Which makes sense; we all come to this with strong suits and weak suits, and they aren't all the same.) Our dean, Rabbi Marcia Prager, likes to say that the va'ad isn't merely graduating students -- they're developing colleagues.

The ALEPH ordination programs don't operate on a set timeline. This is not like college, where one enters with a given class of people and stays with them the whole way through. I had the luxury of being a fulltime student, so my learning took just short of six years. Others with whom I was ordained didn't have that luxury, and took much longer to complete the program's requirements. I had friends who took ten years to finish. And I also had friends who completed the required coursework quickly (one by virtue of already having a PhD in Judaic studies, which exempted him from a lot of classes) -- and were asked by the va'ad to spend another few years in the program anyway, in order to wholly integrate the learning and to finish the process of spiritual formation, even though the academic requirements had been met.

Much of the material we were expected to achieve proficiency in is, I think, common to any rabbinic program: Tanakh, exegesis (various forms of scriptural interpretation), history (Biblical, Rabbinic, medieval, modern), philosophy / ethics / theology / Jewish thought, halakhic literature (including Mishna, Gemara, and Codes), Kabbalah and Hasidut, liturgy, pastoral care and counseling, and so on. Of course, we approached these subjects through Jewish Renewal lens, with courses like "Torah as a mirror for spiritual development" and "Integral halakha." I also did a nine-month unit of Clinical Pastoral Education in a hospital, as do most modern seminary students.

Some of our learning was unique to ALEPH. For instance, learning about the history and Hasidic roots of Jewish Renewal; mastering new cosmology material; classes in deep ecumenism; learning in at least one other religious tradition; integrating central Jewish Renewal teachings, such as paradigm shift, into our learning across the board. I suspect that our neo-Hasidic heritage caused us to delve deeper into kabbalah and Hasidut than most other programs do. Every ALEPH student is required to work with a mashpi'a(h) (spiritual director) the whole way through, and to integrate that personal learning into her/his formation. And then there are multi-year retreat-based programs, like the Davenen Leadership Training Program, which is open to non-ALEPH folks but is required for all ALEPH students.

In ALEPH we talk a lot about the four worlds, and one of the ways that idea manifests is in the expectations around our learning. Some of our learning is physical and practical in nature. Much is intellectual. But in addition to those, we're also always expected to be engaged in emotional learning and spiritual learning, too. Jewish Renewal tends to be experiential, and it's our task to discern how to draw on the rich well of tradition in order to bring awareness of God, prayerful consciousness, and meaningful Jewish life to those we serve. It's not enough to merely learn the history of our liturgy, for instance, or to learn how to recite its words fluently: the real question is, can I lead a service which uses the classical matbe'ah tefillah in a way which opens a channel for people to feel connected with God?

And speaking of leading services -- we're expected to be able to lead proficiently, in a way which breathes life into the liturgy, using any major denominational version of the liturgy. That's part of the fun of being transdenominational. (And yes, it really is fun! Which is probably a sign that I'm in the right line of work.)

In order to apply for senior status, I put together the requisite binder of materials: nearly 250 pages of syllabi, transcripts, sample papers in each category of learning, samples of my unique ritual and liturgical work, and so on. Once a subcommittee of the va'ad agreed that my learning thus far was up to snuff, I became a senior, a status which usually lasts about a year and a half. Everyone with senior status takes one final halakha class together, and each of us writes a teshuvah, a rabbinic-legal responsum, in response to a real question which is live for us or for someone we serve. That teshuvah has to demonstrate both mastery of classical materials, and the ability to appropriately integrate those materials into creative thinking which fits the era in which we live.

I think back with gratitude on my rabbinic school learning all the time. When I seek to care for my community through a funeral and shiva, I think of the lifecycles learning I did with Rabbi Marcia Prager. When I go to translate a Hasidic text in order to have good juicy material for a d'var Torah or a study session, I think of the amazing Hasidic learning I did with Rabbi Elliot Ginsburg. When one of my students asks me a question about Jewish history, I think back on my semesters with Rabbi Leila Gal Berner. When I teach liturgy, or offer brief pearls of context during a service, I think of things I learned from Rabbi Sami Barth. And on, and on, and on.

Is the ALEPH program for everyone? Probably not. You have to be a fairly self-directed and disciplined learner. You have to be comfortable navigating the ratzo v'shov (ebb and flow) of intensive community life followed by dispersal followed by intensive community life again. And, of course, you have to be aligned with Jewish Renewal thinking and ideals. For me, the most central of those ideals are post-triumphalism (the sense that ours is not the only legitimate path to God); deep ecumenism (commitment to engaging meaningfully with other religious traditions); a feminism and egalitarianism which presume that we are all, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, made in the divine image; and commitment to imbuing Jewish life with God-connection and with joy.

When I came home from my first week-long retreat with the ALEPH community, I said to Ethan that I had found my teachers, and that I wanted someday to be a rabbi as they are rabbis. I'm grateful to have had the chance to learn with them, and I hope that in my rabbinate, I honor theirs.

March 12, 2014

What it means to become "perfumed" at Purim

Purim is almost upon us! The full moon falls this weekend, and Purim begins on Saturday evening at sundown. In honor of the coming holiday, here's an adaptation of a teaching from the Hasidic master known as the Sfat Emet. (You can read it at greater length in this post from 2009.)

Purim is almost upon us! The full moon falls this weekend, and Purim begins on Saturday evening at sundown. In honor of the coming holiday, here's an adaptation of a teaching from the Hasidic master known as the Sfat Emet. (You can read it at greater length in this post from 2009.)

1. Above good and evil

We read in the Gemara that it is the duty of a person to mellow (or "perfume") oneself on Purim until one cannot tell the difference between 'cursed be Haman' and 'blessed be Mordechai'." This means raising one's consciousness until one is higher than the tree of the knowledge of good and evil -- in other words, expanding one's consciousness so much that the binary distinctions between good and evil fall away.

We read in the megillah of Esther about Haman's gallows, which is called "a tall tree of 50 cubits." (So there are two trees here: the tree of knowledge of binarism, and the tree which is the gallows.) There's an ancient teaching that there are 49 "gates" (or levels) of impurity, and the 50th level is the level of holiness. (There's that number 50 again -- like how Shavuot is the 50th day after the 49 days of counting the Omer.)

If we can ascend past the 49 levels of impurity, we reach the 50th level where everything is holy. If we can reach that high level, we've gone higher than the tree of knowledge of good and evil; we've reached God's vantage, from which everything is good. "Perfuming" ourselves on Purim means opening our minds and ascending to that high God's-eye-view place.

2. Defeating Amalek

Amalek is the name given to the tribe which attacked the Israelites from behind during the Exodus from Egypt. Haman, who sought to destroy the Jews of Persia in the story of Esther, is considered to be a descendant of Amalek. Amalek and his ilk exist on every level of spiritual understanding except the top one, which is the level of holiness. (Maybe the Sfat Emet is saying that Amalek exists in some form in all of us, except for those who are at the very holiest level of spiritual understanding.)

Amalek pursues evil on those lower 49 levels, but at the 50th level, Amalek's power disappears. When Amalek attacked our ancestors, Moses lifted up his hands to God, and as long as his hands were upheld, the Israelites were able to rout the enemy. Moses reached up to God and Torah, and Amalek was defeated. God and Torah are what we find at that 50th gate or rung of spiritual understanding. So: ascending to that high level of spiritual consciousness also enables us to live without fear of our enemies, because at that high level, enmity can't harm us.

3. Accepting the Torah on Purim

There's even a teaching that our ancestors, the ancient Israelites, accepted the Torah on Purim.

What? you ask. Isn't Shavuot the anniversary of when we accepted the Torah? Well, yes. But there's also a midrash which says that we accepted the Torah at Shavuot under duress -- that God held the mountain over us like an inverted barrel, and we accepted Torah rather than perish. But another sage says, "Even if that is so, they re-accepted the Torah in the days of Achashverosh," pointing to a line from Esther which said that we "received it upon ourselves" -- he says that what we received, at Purim, was the highest form of Torah.

And when we approach Purim now with the appropriate consciousness -- awareness that at the highest levels there are no differences between good and bad, between Haman and Mordechai, between "my side" and "your side" -- we can access the highest Torah once again.

That's what it really means to become "perfumed" or "mellowed" -- not to get so drunk we forget who the good guys and bad guys are, but to become so enlightened that we see the unity beyond all differences. When we access that kind of perfume, we're breathing the scents of spices which filled the world at the time of the revelation at Sinai -- maybe even the spices which filled the world at the first moments of creation.

Happy Purim!

Image source: Jaison Cianelli.

March 7, 2014

Interview with Jen Marlowe, coauthor of I Am Troy Davis, in Zeek

Earlier this week I had the privilege of interviewing Jen Marlowe for Zeek magazine. We spoke about her new book, I Am Troy Davis, co-authored with Martina Davis-Correia, which tells the story of Troy Davis who was executed by the state of Georgia. We also talked about The Hour of Sunlight, the book she co-authored with Sami al-Jundi; about the death penalty and the state of the American criminal justice system; about how her Jewishness informs her activism; and about where she finds cause for hope. That interview is now published online, and here's how it begins:

I first encountered Jen Marlowe’s work thanks to blogger (and frequent Open Zion, Ha’aretz, and Forward contributor) Emily L. Hauser. She had written a review of The Hour of Sunlight: One Palestinian’s Journey from Prisoner to Peacemaker, which Marlowe had co-authored with Sami al-Jundi. I read the book, found it powerful though not always comfortable to read — and ultimately partnered with other local organizations to bring Marlowe to my town to speak about her work.

I knew then that she was already working on a new book, also co-authored. That new book is now out. It’s called I Am Troy Davis, and it’s written by Marlowe and Martina Davis-Correia along with Troy himself.

Much like The Hour of Sunlight, I Am Troy Davis shines a spotlight on systemic injustice not by speaking in generalities, but by telling one person’s story — and thereby opening up the experiences of countless others who are in similar shoes. I spoke with Marlowe about these two books, how her Judaism animates her work, and what we as readers can do to strengthen justice in an unjust world.— RB

ZEEK: Tell us about I Am Troy Davis. What is the book, and how did you get involved with it?

JM: I Am Troy Davis grew out of my relationship with Troy and with the Davis family. Troy was a man who spent 20 years on Georgia’s death row despite a very compelling case for his innocence. When that compelling case came to the attention of human rights organizations and then the media, it led to a worldwide movement, both to try to prevent the travesty of justice of Troy being executed, and also toward the abolition of the death penalty, especially when there’s such recognition of the human error that the system is rife with. A system like that has no business making the decision to take a life.

The book grew out of my friendship with him and his family. It was my way of helping them tell their story.

Read the whole thing: Broken Justice and the Death Penalty: Q and A With Jen Marlowe, Co-Author of I Am Troy Davis.

A cinquain about morning prayer (and after)

MORNING PRAYER

Leaves

an echo on

my arm, a spiral fading.

I hope the imprint on my heart

stays.

This little poem is a cinquain, a five-line poem. I've posted this kind of poem here before -- see last year's Daily April poem: a cinquain -- though last year's cinquain was written with both syllabics and stresses in mind, and this one only follows the pattern of stresses. (One stressed syllable in the first line; two stresses in the second; three; four; and then one again.)

The "echo" referenced in the poem -- this is probably obvious to those who wear tefillin, but perhaps less so to those who have never tried the practice -- is the winding mark left on my arm by the tefillin straps, which fades over the course of half an hour or so. Speaking of which, there's a new tefillin category on this blog; if you're interested in posts having to do with tefillin, click on the "tefillin" link in the category cloud in the sidebar, or click here.

Shabbat shalom!

March 6, 2014

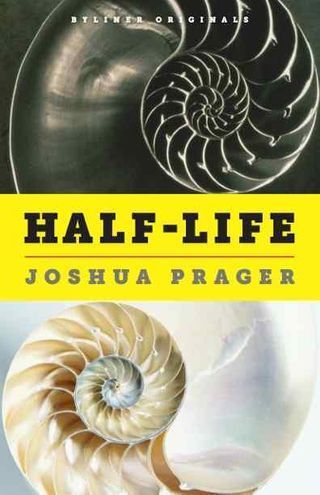

Joshua Prager's Half-Life

I recently finished Joshua Prager's Half-Life: Reflections from Jerusalem on a Broken Neck. Prager was a young man of nineteen studying in Jerusalem when the bus he was riding in was slammed by another vehicle -- not an act of terrorism, as one might have assumed, (especially when a Palestinian driver hits a bus full of Jews), but simple carelessness and bad driving. His neck was broken, a moment of rupture which divided his life irrevocably into a "before" and an "after."

I recently finished Joshua Prager's Half-Life: Reflections from Jerusalem on a Broken Neck. Prager was a young man of nineteen studying in Jerusalem when the bus he was riding in was slammed by another vehicle -- not an act of terrorism, as one might have assumed, (especially when a Palestinian driver hits a bus full of Jews), but simple carelessness and bad driving. His neck was broken, a moment of rupture which divided his life irrevocably into a "before" and an "after."

The book's narrative curls around and loops in on itself. We read about Prager as a hale and hearty student; we read about him paralyzed; we read about the morning of the crash, and the last bodily freedom he remembers; we read about physical therapy and the excruciating effort to regain bodily control. Learning to breathe and to sit again. From quadriplegic to hemiplegic to walking, albeit with difficulty, with a cane.

We return with Prager to Jerusalem, and as voyeurs on his shoulder we accompany him as he slowly makes his way through the city where his life changed. Navigating, for instance, the cobbled streets and uneven city curbs which I remember from pushing a stroller there in the summer of 2008 with my housemates' three-year-old in tow.

This book is full of poignant tension between what was, and what is, and what might yet be. The same could be said of Jerusalem, with its storied history and contested present and future. As Prager himself notes: "This ancient city is a palimpsest, its narratives written and rewritten on white stone." This memoir's structure evokes that quality. At the beginning of any new section, we might be in the now or we might be in the then -- or any moment in between. Even in the now, the then peeks through.

Prager approaches his subject with clear eyes and deft turns of phrase. I admire his ability to write so candidly about his experience, without sentimentality and without sparing anyone, including the reader. The scene where he goes to meet the driver of the minibus responsible for his injuries is a particularly fine example of that. He doesn't sugar-coat and he doesn't flinch from what is -- and he also resists the urge to demonize or oversimplify. (You can hear him tell that story in his TED talk, which I've linked to below.)

One of the book's most memorable moments for me (as a rabbi and sometime hospital chaplain) is the scene where the rabbi emeritus of his synagogue walks into his hospital room and loudly prays over his prone body. Prager writes:

I was mortified. No, rabbi! NO!

But I, who one month before had wrestled a trio of classmates, pinning each, was unable to fend off a rabbi in his eightieth year. And as the litany unfurled -- God asked to shine his face upon me, to be gracious to me, to lift up his countenance to me, to give me peace -- I wished to disappear. But I saw over my stockinged feet that the congregation was not listening, the yellow man beside me, his saffron urine bagged between us, minding his tea. And so I succumbed to a blessing.

In some ways this whole memoir feels to me like a book about succumbing to blessing with grace, and also a book about fighting for every inch of recovery and understanding. The two coexist sometimes uneasily, and that tension is part of what drives the narrative forward.

Prager resists the platitudes -- "everything happens for a reason" or "God only gives us what we can handle." (Two of the top sentences on my list of things never to say to hospital patients, by the by.) But he also resists, I think, the sense that if God doesn't have a "plan" then our lives is meaningless. I experienced this book as Prager's work at making meaning out of his own life, out of the lived Torah of his human experience. And in reading about his process, we join him in making, or finding, meaning too.

You can read an excerpt online here. To my surprise, the Kindle edition is only $3.99 on Amazon. Worth a read.

For more:

Joshua Prager's TED talk, In search of the man who broke my neck [video]

The Q & A: Joshua Prager: Reconstituting a Self, The Economist

March 5, 2014

Not a sign of defeat, but a sign of engagement

I just shared a post about prayer and parenthood. (Which has garnered some lovely comments, by the way; thanks, y'all!) Next up, I wanted to offer something different. Variety being the spice of life, and all that. But apparently the writing I'm doing this week is either for other sources (and therefore not publishable here), or is on these same themes. As my mentor Jason Shinder used to say, "Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work." I guess this intersection is the work in which I'm immersed at this moment in time.

Lately, in fits and starts, I've been reading Verlyn Klinkenborg's Several short sentences about writing. I've dogeared the page where this appears:

But if you accept that writing is hard work,

And that's what it feels like while you're writing,

Then everything is just as it should be.

Your labor isn't a sign of defeat.

It's a sign of engagement.

The difference is all in your mind, but what a difference.

He's talking about the writing life, of course, though (predictably) I've been thinking of this as pertaining to spiritual life, too. Writing life, spiritual life: both will inevitably contain times when "the thrill is gone," when the spark doesn't feel as though it's there; times when one has to work hard just to get the boulder moving up the hill, or when the journey is arduous instead of scintillating. And that's not a sign of failure, as Klinkenborg notes: it's a sign that one is engaged in something that matters.

Or, taking his words in a different direction, try this paraphrase:

But if you accept that parenting is hard work,

And that's what it feels like while you're parenting,

Then everything is just as it should be.

Your labor isn't a sign of defeat.

It's a sign of engagement.

The difference is all in your mind, but what a difference.

Parenting is hard work! And it's supposed to be. Though rearing a four-year-old presents different challenges than caring for an infant, it's still work. I still struggle to maintain the good humor, the equanimity, the right balance of gentleness and firmness to which I aspire. I still fall down on the job, snap at our son when I didn't mean to, drive myself up a tree with fruitless attempts to convince him to try a food which he doesn't already know he enjoys. But if I take Klinkenborg to heart, then the fact that parenting is hard work doesn't mean I'm failing at it -- on the contrary, it means I'm doing it well.

Just so with spiritual life. Sometimes my prayer life and my spiritual consciousness "jut flows," and sometimes it feels as though the channels are blocked, as though God isn't listening -- or maybe as though I can't muster the focus to be listening in return. Sometimes I can't wait to set aside time for daily prayer, and other times I want to skip it all and just go back to sleep. That doesn't mean I'm failing in my spiritual life. If I'm paying enough attention to notice that sometimes it's easy, and sometimes it's hard, then I'm paying attention, period, and that's an essential component of spiritual life.

And just so with writing. Whether I'm writing poetry, or blog posts, or essays, there's work involved in choosing the right words and putting them in the right order -- reading them aloud, winnowing a word here and a phrase there, reading them aloud again -- paying attention to white space, scrapping the boring words and replacing them with words which (ideally) sing. That's the craft of writing. Sometimes it feels like flying, but more often it feels like building a stone wall, testing it for soundness, taking it apart, building it again. (Which is why Stone Work, by John Jerome, manages to be simultaneously about building a stone wall and about the writing life. I miss you, John.)

As Thomas Lux wrote in his poem "An Horatian Notion" (one of the few poems I've ever memorized):

...Inspiration, the donnée

the gift, the bolt of fire

down the arm that makes the art?

Give me, please, a break!

You make the thing because you love the thing

and you love the thing because someone else loved it

enough to make you love it.

(I wrote a kind of d'var Torah on that poem a while back -- What are we here for?) Poetry doesn't come from a bolt of fire. Sustained spiritual practice doesn't either. Though sometimes peak spiritual experiences can involve a kind of ecstatic blaze, the way to cultivate that flame is to tend it carefully, day in and day out, even when you don't feel like keeping the fire burning. The way to cultivate poetry is to keep writing and revising it. And as for parenting -- I don't think one gets a choice, having become a parent, about whether or not to keep doing it on a daily basis! These are long-haul journeys. We enter into them trusting that there will be blessings to balance the labor.

There's something beautiful, to me, in the idea that these lifelong practices take work, and that they're supposed to take work. It's okay if writing is hard -- if spiritual life is hard -- if parenting is hard. "The labor isn't a sign of defeat. / It's a sign of engagement." It's how we know we're actually in the world, doing work that matters.

March 2, 2014

Pekudei: lessons on sacred space and on cultivating Mystery

Here's the d'var Torah which I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Here's the d'var Torah which I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

At the end of this week's Torah portion, Pekudei, we read about Moshe setting up the mishkan, the place where the Shekhinah would dwell -- in English, the "tabernacle." He sets up the tent, erects screens to delineate different spaces, lights lamps and makes offerings. We learn that he and Aaron and Aaron's sons would wash their hands and feet upon entering and upon approaching the altar, a physical act intended to cultivate spiritual purity of intention. And we read that a cloud of God's presence covered the tent, and filled the tent so fully that no one could enter. When the cloud lifted, the people would journey; when the cloud descended, they would camp.

This taste of Torah teaches us some things about sacred space. Sacred space requires careful preparation. Sacred space requires attentiveness to detail. Moshe sets up the screens in part to protect the people from the spiritual power of God's presence; sacred space needs to be safe. Sacred space makes demands of us: that we keep the light of memory burning. That we cleanse our hands of wrongful actions, and our feet of the dust from unjust or unkind paths. This is how we set the stage for an encounter with God.

Of course, this encounter doesn't only happen in synagogues. The labor and delivery room where our son was born felt, to me, so suffused with God's Presence that there was barely space for people in the room. When I have been blessed to sit at the bedside of someone who is dying, I have felt God's Presence hovering over the bed like a mother bird. Maybe you have felt that Presence at those times too -- or while walking in the woods, while breathing in the charged air just before a storm, while immersing in the endless motion of the sea.

When the cloud of glory lifted, the people would travel. We can't live in exquisite awareness of God's presence all the time. No matter how powerful the experience -- whether it's prayer or yoga, childbirth or seeing the aurora borealis -- we have to return to mochin d'katnut, small consciousness. That's how we're able to venture forth, to do our work in the world. And when the Presence descends again, we enter mochin d'gadlut, expansive consciousness -- and we are transfixed for a time by the experience of being in the Presence of Mystery.

If Mystery can be experienced in these solitary and personal ways, why go to the trouble of building the mishkan? Because the mishkan is the spiritual technology given to our ancestors for cultivating that experience. In coming together to build a beautiful place where God's presence could dwell, they cultivated community, and they cultivated spiritual life. A mystical experience might happen in the wilderness, or at a moment of great emotional import -- but it can't be predicted. The mishkan was our way of domesticating the peak experience. Bringing it home. Building a home for it.

In order for a spiritual practice to be sustaining, in order for connection with God to be there when we need it, some maintenance is required. If I wanted to be able to hike Mount Greylock, I'd have to exercise regularly enough that when the mountain is before me, I'd have the endurance to climb. If we want to be able to ascend to the spiritual heights of connection with God, we have to exercise our spiritual muscles regularly enough that when the opportunity for connection is before us, we have the strength and the tools we need to make that trip.

Once our ancestors practiced daily connection with God through fire: burning incense, burning sacrifices, sending a pleasing odor to God. Today we practice that connection through prayer: saying, in Anne Lamott's words, "help" and "thanks" and "wow" until they become second nature. Today the mishkan that we tend is a Mishkan T'filah, as it were; a tabernacle of prayer. It's the community where we practice our help and thanks and wow. It's the altar of our own ardent hearts.

Image of the cloud of glory over the mishkan: found via google image search. Artist unknown. If you can identify the artist, please do and I'll add attribution!

March 1, 2014

Privilege, prayer, parenthood

There's a teaching from the Maggid of Mezritch about morning prayer. I love this teaching -- and I also struggle with it. Here it is:

There's a teaching from the Maggid of Mezritch about morning prayer. I love this teaching -- and I also struggle with it. Here it is:

Take special care to guard your tongue

before the morning prayer.

Even greeting your fellow, we are told,

can be harmful at that hour.

A person who wakes up in the morning is

like a new creation.

Begin your day with unkind words

or even trivial matters --

even though you may later turn to prayer,

you have not been true to your creation.

All of your words each day

are related to one another.

All of them are rooted

in the first words that you speak.

(That's as cited in Your Word is Fire: The Hasidic Masters on Contemplative Prayer.)

It's a beautiful teaching. I love the idea of taking special care to guard what comes out of my mouth, especially first thing in the morning. I love the idea that when one wakes up in the morning one is like a new creation. I love the idea that all of the words I will speak in a day are rooted, somehow, in the first words I uttered upon waking. What a beautiful idea, to keep silence until it's time for morning prayer, and to begin the day with praise and song. I've done that on retreat, and it's a joy.

Here's the thing, though: most of us don't live on retreat. Most of us don't have the luxury of beginning the day in perfect silence and contemplation, gliding into a joyful morning service, and only then engaging in trivial or ordinary speech. Most of the people I know wake up to someone's needs: the needs of children, the needs of parents, the needs of a sick or disabled partner, the needs of animals. Who has the luxury of avoiding "trivial matters" until after morning prayer? Certainly not me.

I think it's possible that the holy Maggid, may his memory be a blessing, was speaking out of a kind of privilege. Something tells me he wasn't waking up to care for a child who chatters and expects answers -- presumably that was his wife's job.

Waking up to care for a child is a privilege, in the sense that I'm grateful to have the opportunity to do it. But waking up and being able to devote oneself entirely to spiritual concerns, because someone else is doing the familial caregiving -- and not noticing that, nor thinking about the fact that for the person doing the caregiving, the day necessarily unfolds differently -- is a sign of privilege. It's unconscious, but that doesn't make it any less present. (In the words of author Cat Valente, "Your privilege is comprised of the questions you’ve never had to ask.") Most of the beautiful spiritual texts at our disposal were written by men, because for most of our religious history, men are the ones who've access to the lives conducive to writing those texts.

Of course, in the Maggid's paradigm, prayer was a mitzvah incumbent upon men but not upon women for precisely this reason. Women were presumed to have familial obligations which exempted us from prayer. (I've written about this before, mostly since I became a parent -- see, for instance, the post Time-bound, 2010.) But I live in an intentionally egalitarian setting, spiritually and otherwise. His gender-determined world is not the world I inhabit, nor the kind of community in which I serve. And yet I recognize that my world isn't wholly liberated, either. Even in my egalitarian community, it's most often women who do the lioness' share of the caregiving -- not always, but often. And I suspect that often we measure our progress in spiritual life against a yardstick designed for people who don't have those responsibilities.

I don't think the Maggid could have imagined the life I lead: ardently religious but not always in ways he would have recognized; invested in prayer and in God, but also accustomed now to finding new ways of living with prayerful consciousness, ways which don't require me to set aside my parenting responsibilities in order to enter into relationship with God. For that matter, I don't think it's only women who struggle with these choices -- not in today's paradigm. Those with caregiving responsibilities, and those who work multiple jobs to get by, and probably other groups of people I'm not thinking of (so feel free to chime in!) -- I suspect that most of us today experience tension between our responsibilities and our yearned-for spiritual lives.

How might I reframe the Maggid's teaching? Maybe something like this:

Take special care to speak with kindness

when you first wake to those for whom you care.

Even in greeting your child, patient, partner, or loved one

you can cultivate compassion and lovingkindness.

A person who wakes up in the morning is

like a new creation.

If you begin your day with frustration

or, worse, resentment --

though you may later turn to gentleness,

you've started the day on the wrong foot.

All of your words each day

are related to one another.

All of them are rooted

in the first words that you speak.

If you would adapt his teaching differently, I'd love to see your version in comments. (Or if you want to keep his teaching precisely as it is -- which I admit I do too! I both want to preserve it, and want to adapt it. I think I need both.)

I don't want to have to choose between "spiritual life" and "caring for my child." I want to be able to engage in spiritual life through caring for my child. I want to make caring for my child part of my spiritual life. Spiritual life isn't what happens after I'm able to put my caregiving responsibilities aside. Spiritual life and spiritual practice are -- they have to be -- bigger than that, deeper than that, richer than that. (I've written about this before, too -- see This is spiritual life, 2011.) Maybe that means spiritual life takes different shapes. Maybe it means we need a more expansive sense of what spiritual life means.

Here's one more teaching about prayer from that same English compilation. This one's from Zavat Ha-Rivash, a collection of teachings attributed to the Baal Shem Tov and his disciple the Maggid of Mezritch:

There are times when you are not at prayer

but nevertheless you can feel close to God.

Your mind can ascend even above the heavens.

And there are also times,

in the very midst of prayer,

when you find yourself unable to ascend.

At such times stand where you are

and serve with love.

"At such times stand where you are and serve in love." I love that. Wherever we are -- whatever we're doing -- we can seek to wholly inhabit that place, and to serve in love. To serve the people for whom we care. To serve God. To serve God through serving the people for whom we care. To serve the spark of God in our loved ones; to see the spark of God in our loved ones. Stand where we are, and serve in love. It's a beautiful ideal... and I recognize that I can't always manage that, either. I can aspire to it! But as with any other spiritual practice, there are times when it comes easily, and times when I can't seem to get there at all.

That's part of why I'm grateful to have the privilege of going on retreat, from time to time. (Or just going on a rabbinic business trip where I get to focus exclusively on my rabbinic life instead of on my other responsibilities for a few days.) Relinquishing my parenting responsibilities for a few days can be a gift, as can focusing instead on cultivating the life of the spirit and nurturing my connection with God. But what do I do when I inevitably fail, in ordinary life, to measure up to the kind of focused spiritual immersion I can manage when someone else is preparing the food, doing the dishes, and looking after my child?

The answer has to be that the goal isn't to replicate the retreat experience at home, but to bring the sustenance of the retreat experience into my householder spiritual life. Which is also a ordinary mom life, and I don't want to fall into the false dichotomy of privileging the "spiritual" part of my life over the "mom" part. In my best moments, I can glimpse the life of the spirit elevating and enlivening the alphabet cereal and the board games and the books before bedtime. The mom life is a spiritual life. Or it can be, when I'm awake to it. And when I'm not able to access that awareness, at least I can try to stand where I am and to bring love to whatever task is at hand.

(.)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers