Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 163

April 2, 2014

Tell - for #blogExodus day 2

Every year at the seder we retell our central story: once we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, and now we are free. Once we were trapped in the constriction of terrible circumstance, and now we can breathe and stretch and shape our own choices. Once we were forced to live in servitude to an earthly power; now we are free to choose to live in service to the love and the hope and the power which are beyond all earthly imagining.

Every year at the seder we retell our central story: once we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, and now we are free. Once we were trapped in the constriction of terrible circumstance, and now we can breathe and stretch and shape our own choices. Once we were forced to live in servitude to an earthly power; now we are free to choose to live in service to the love and the hope and the power which are beyond all earthly imagining.

In the traditional haggadah we read:

In every generation a person must see himself as though he himself had been brought forth from Egypt, as it is said: 'And you shall speak to your child on that day, saying, it is because of what God did for me when God brought me out of Egypt. Not for our ancestors alone did the Holy Blessed One wreak this redemption, but we too were redeemed along with them.'

We tell the story as though it had happened to us, because it does happen to us. It is always happening to us.

In every life there are times of constriction and tightness. The name Mitzrayim, "the narrow place," contains the root tzar, narrow. This is the root of the word tzuris, suffering. In every life there is suffering. We all know this, though sometimes we don't want to acknowledge it. (I certainly don't want to acknowledge it most of the time. As though by ignoring it I could make it less true.) But here's the radical part of what our tradition teaches: in every life there is also redemption.

That's the central story we tell, the story which makes us the Jewish people. We tell it each year during the Pesach seder. We tell it each Friday when we remember the Exodus in the kiddush blessing over wine. We tell it every day when we remember the Exodus in the ge'ulah blessing of daily prayer. We were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, we have been in the narrow place of constriction and suffering, and the Holy One of Blessing brings us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. We are the people who tell the story which leads from slavery to redemption, from constriction to openness, from sorrow to joy.

We each have personal stories which we habitually tell. Stories about our childhoods, stories about our families, stories about our choices and our circumstances. What are the stories you tell about your life? What would it take for you to tell a story of wholeness and redemption, like the story our people tells every day, every week, every year -- the story we tell which makes us who we are?

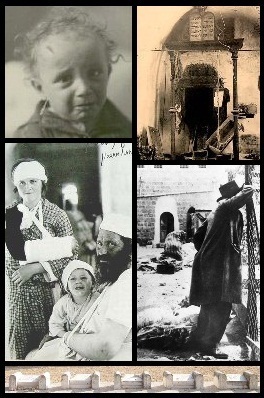

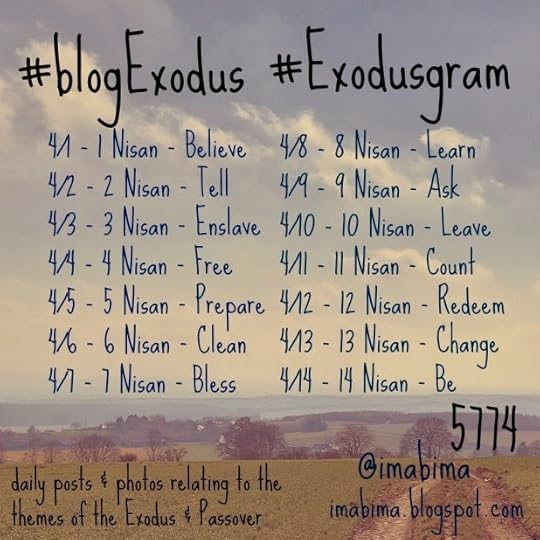

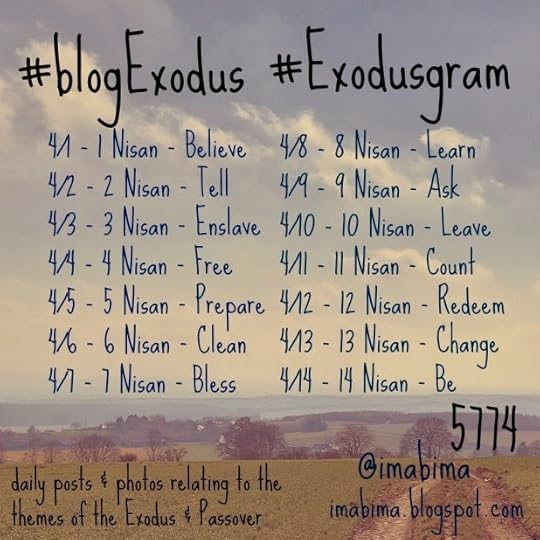

This post is part of #blogExodus, a carnival of posts on themes relating to the Exodus and to Passover, instigated by the ever-wonderful ImaBima. Follow it by searching for the #blogExodus hashtag on Twitter or wherever you habitually look for things.

Daily April poem for #NaPoWriMo, and #blogExodus 1 - Believe

HEBRON

How much is us? Why shall we not

in such burning place live out our allotments?

nothing looks good on paper

if you can tame it, you can have it

-- from "Not This Mouth" by Jasper Bernes

the heart hot with shrapnel

where a man shot a baby in her carriage

where a man shot a child who held a stone

the belly twisting sour

where those people hung their hateful flag

its colors like a stick in my eye

the mind which insists

there is only one story and it is ours,

lists our traumas, every one their fault

the spirit lofted toward God

by the air of this holy place

which only we should breathe

can we tame our animal hatreds

and escape this constriction

I want to believe

This year, National Poetry Writing Month and #blogExodus start at the same time. This is something of a brain-bender for those of us who are active both in the poetry-writing world and the preparing-for-Pesach world. (It's not like I have anything going on this month or anything.)

This year, National Poetry Writing Month and #blogExodus start at the same time. This is something of a brain-bender for those of us who are active both in the poetry-writing world and the preparing-for-Pesach world. (It's not like I have anything going on this month or anything.)

Given that these two things are overlapping this year, I don't know that I can promise that I'll manage both on a daily basis. (I don't know that I'll manage either on a daily basis!) But we'll see where things go.

The first NaPoWriMo prompt invited us to click through to the Bibliomancy Oracle and see what quote we got, and then to write a poem sparked by that quotation. The first blogExodus theme is "believe." I just went on a very intense Dual Narrative Trip to Hebron (about which I wrote a rather lengthy post, but which is still on my mind).

Today's poem came out of all of these.

Daily April poem for NaPoWriMo: based on a non-Greco-Roman myth

LEVIATHAN

Vaster than any known creature who lives in the deep!

Prayers encircle your horns. Light shines from your eyes.

Most of all you are lonely: God reconsidered your power

and killed your companion, salting away her flesh

as a feast for the righteous at the end of time.

These are the stories we whisper where you can't hear.

Each day you eat a whale whole and drink the Jordan down.

Maybe it's your fault there isn't enough water anymore.

To the dispossessed, the defending army is a leviathan

destroying homes with a flick of its mighty tail.

To the other side, the riotous rabble are numerous

as the scales on leviathan's back, deadly as its toothy maw.

Can that story change, or are we locked like bullets

into the rifled helix which points to the fearsome day

when the triumphant will stitch a sukkah from your skin

when we will have slain the greatest mystery of the sea?

The April 2 NaPoWriMo prompt suggests the writing of a poem arising out of a non-Greco-Roman myth. I chose Leviathan - drawing on a number of different midrash about the great sea-creature, many of which are cited in its Wikipedia entry (to which I just linked.)

Of course, since I am still processing my recent trip to Israel and the West Bank, thinking about leviathan's might and power led me to thinking about how each side in the Israeli/Palestinian conflict sees the other as the powerful aggressor, so that's in this poem too.

Featured in Soul-Lit

I'm delighted to be able to let y'all know that I am the featured poet in the current issue of Soul-Lit, a journal of spiritual poetry.

One of the magazine's editors, Wayne-Daniel Berard, interviewed me for the issue's central feature story. Here's one question-and-answer, to whet your appetite:

Can you describe the relationship between your being a rabbi and being a poet?

For me the two are very consonant. In both professions, words matter. When it comes to Torah and prayer, the words are incredibly important. Our mystics tell us that even individual letters of the Torah have the capacity to contain deep meaning! The words we speak in prayer are polished and honed by years of use. One of our daily prayers tells us that God speaks the world into being in every day. Like God, we too can speak worlds into being, and poetry is one of the ways we do that.

When we speak words during religious ritual -- a baby-naming, for instance, or a wedding, or a funeral -- those words are carefully-chosen and important, and they create change in the world around us. In poetry, too, words matter deeply. I love the way that both of these worlds regard words.

I also think that being a rabbi, being a mother, being part of the wide world -- all of these things make me a better poet, because they keep my eyes and my heart open to the things around me. The more I pay attention, the more engaged I am with my world, the more I have to draw on when I write poems.

And, I think that being engaged with poetry helps me to be a good rabbi. One of my spiritual directors when I was in rabbinic school is a longtime scholar of the Baal Shem Tov, and he always had relevant and meaningful Besht quotes to offer. I do the same with poetry. I often share poems with congregants when I think those poems might speak to where they are or might offer a kind of spiritual medicine which they need.

In a practical sense, my congregational job is technically half-time, which means there is spaciousness in my life for poetry. Of course, congregational obligations sometimes push poetry out of the way; if there is a funeral, for instance, that trumps everything. But I try to maintain space in my life for both of my vocations. I think they enrich each other.

Read the whole interview here: Soul-Lit Feature. Along with that interview, they published six of my poems: Belief, Baruch She'amar, Meditation on Removing Leaven, No Limit, Word to the Wise, and Standing at the Edge. The issue contains a lot of other wonderful poems as well -- browse the whole listing here.

My thanks to the editors for kindly featuring my work!

April 1, 2014

#NaPoWriMo1, #blogExodus 1 - Believe

HEBRON

How much is us? Why shall we not

in such burning place live out our allotments?

nothing looks good on paper

if you can tame it, you can have it

-- from "Not This Mouth" by Jasper Bernes

the heart hot with shrapnel

where a man shot a baby in her carriage

where a man shot a child who held a stone

the belly twisting sour

where those people hung their hateful flag

its colors like a stick in my eye

the mind which insists

there is only one story and it is ours,

lists our traumas, every one their fault

the spirit lofted toward God

by the air of this holy place

which only we should breathe

can we tame our animal hatreds

and escape this constriction

I want to believe

This year, National Poetry Writing Month and #blogExodus start at the same time. This is something of a brain-bender for those of us who are active both in the poetry-writing world and the preparing-for-Pesach world. (It's not like I have anything going on this month or anything.)

This year, National Poetry Writing Month and #blogExodus start at the same time. This is something of a brain-bender for those of us who are active both in the poetry-writing world and the preparing-for-Pesach world. (It's not like I have anything going on this month or anything.)

Given that these two things are overlapping this year, I don't know that I can promise that I'll manage both on a daily basis. (I don't know that I'll manage either on a daily basis!) But we'll see where things go.

The first NaPoWriMo prompt invited us to click through to the Bibliomancy Oracle and see what quote we got, and then to write a poem sparked by that quotation. The first blogExodus theme is "believe." I just went on a very intense Dual Narrative Trip to Hebron (about which I wrote a rather lengthy post, but which is still on my mind).

Today's poem came out of all of these.

March 31, 2014

Returning to Hebron - on a Dual Narrative Tour

One of the things I knew I wanted to do, upon returning to Israel for the first time in many years, was to go with Eliyahu McLean to Hebron on his Hebron Dual Narrative Tour. I had heard about the trip from a rabbi friend, who wrote to me:

One of the things I knew I wanted to do, upon returning to Israel for the first time in many years, was to go with Eliyahu McLean to Hebron on his Hebron Dual Narrative Tour. I had heard about the trip from a rabbi friend, who wrote to me:

Eliyahu's trip to Hebron is amazing and wonderful and done in tandem with a Palestinian guide. I cannot recommend the experience highly enough... on Eliyahu's trip, one spends 1/2 the day speaking with Jewish settlers, and 1/2 the day speaking with Palestinians. One experiences what is happening on the ground there. It is painful, complex, and not rhetorical or polemical. It is not either/or to go with Eliyahu, but both/and in every sense of the word.

Not either/or, but both/and: that sounds right up my alley. Eliyahu was the first person ordained by Reb Zalman as a Rodef Shalom, a seeker of peace. (Learn more about his work at Jerusalem PeaceMakers, which he co-founded along with the late sheikh Abdul Aziz-Bukhari, may his memory be a blessing. And here's an interview with Eliyahu at JustVision. While I'm at it -- let me mention that Eliyahu and my friend Reuven collaborated on transcribing the story of Reb Zalman Among the Sufis of Hebron, which I have cherished for years.)

I had visited Hebron once, in 2008, but not on this kind of dual-narrative trip. I was eager to see what I would learn. So last Wednesday morning I woke up early at the Ecce Homo convent and made my way through the Old City, out the Damascus Gate, and all the way down Street of the Prophets to meet up with the group. We were a mixed group of internationals: from Iceland, Denmark, Germany, Canada, the United States, and more. As far as I could tell, I was the only Jew on the tour.

I had visited Hebron once, in 2008, but not on this kind of dual-narrative trip. I was eager to see what I would learn. So last Wednesday morning I woke up early at the Ecce Homo convent and made my way through the Old City, out the Damascus Gate, and all the way down Street of the Prophets to meet up with the group. We were a mixed group of internationals: from Iceland, Denmark, Germany, Canada, the United States, and more. As far as I could tell, I was the only Jew on the tour.

(Long post ahead -- more than 4000 words, and many images, too. I hope you'll read the whole thing, despite its length.)

One of the first things that Eliyahu said to us was, "Remember that this trip is about dual narratives. You may feel at times that they are dueling narratives!" The first half of the day was spent with Eliyahu as our guide in the Jewish area of Hebron, which is called H2. H2 consists of about 20% of Hebron, geographically speaking, and Palestinians are not allowed there. He reminded us that Hebron is one of Judaism's four holy cities, was the first capital from which King David reigned, and is considered in Jewish tradition to be second only to Jerusalem.

Eliyahu speaks to our group; two Palestinian women at the edge of Shuhada / King David street.

He pointed out that both sides in this conflict tend to paint themselves as the victims. For instance: the Palestinian narrative holds that the closure of Shuhada street (which Jews call King David street) is a form of apartheid. That street had been a primary market thoroughfare before it was closed by the IDF. Now it is a ghost town of shuttered shops (and Palestinians are forbidden from walking on most of it), which the Palestinian narrative sees as a land grab and an exercise of power and control. The Israeli narrative says that King David street was closed because of suicide bombings and other attacks on Jews, and points out that Palestinians have access to 97% of the city while Jews are confined to a mere 3%, so clearly it's the Jews, not the Palestinians, who are the victims. (That's one example of incompatible narratives; over the course of the day we encountered many others.)

Beit Hadassah; formerly a hospital, now a museum.

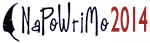

One of the first places we visited was Beit Hadassah. The Jewish community began construction on this building in 1893. In 1912, when Hadassah was established, this became the first clinic in the holy land, which treated Arabs and Jews alike. After the pogrom of 1929, the Jews of Hebron were forcibly evicted by the British. After 1948, Hebron was under Jordanian rule; after the Six-Day War in 1967, Hebron came under Israeli control again. The building was reclaimed dramatically in 1979 (initially by a group of women and children who moved in and refused to decamp.) Now the ground floor is the Hebron Heritage Museum, a museum to Jewish history in Hebron. The earliest material didn't particularly impact me, but the 20th-century material touched me in ways I hadn't expected. The room dedicated to the pogrom of 1929 was so emotionally affecting that I almost started weeping in front of a room full of strangers.

In the Hebron Heritage museum. Eliyahu in front of a mural; pointing at photographs from the 1929 pogrom.

As Eliyahu told the story of the 1929 massacre, it began with the Mufti Haj Amin al-Husayni in Jerusalem who began broadcasting that the Jews were trying to take over the Temple mount -- actually, Eliyahu said, they were just trying to set up a mechitzah for separate-gender prayer at the Western Wall. (About which I have complicated feelings, but that's an entirely different post.) Anyway, there was rioting in Jerusalem, and the British forces came to Hebron and tried to provide weapons for the Jewish residents there in case self-defense were needed. The Jews, Eliyahu told us, refused the weapons. "If we take them, our friends will think we don't trust them. We know these people." Jews and Muslims had lived peacefully together in Hebron for generations, celebrating weddings and lifecycle events together. "They didn't see each other as Jews and Muslims," Eliyahu told us; "they were all Hebronites together."

But when the Mufti's radio broadcasts went out from Jerusalem, a group of Muslims in Hebron caught his nationalist fervor, armed themselves, and began marching to Jerusalem to attack. They were turned back midway... so they returned to Hebron and attacked there, instead. 67 members of the Jewish community were killed, and hundreds of others injured. Homes were trashed. Torah scrolls were desecrated. The photographs of this devastation are terrible to behold.

Source: wikipedia. Other images showed the desecrated synagogue and steps running with blood.

Many Jews attempted to take refuge in the home of Rabbi Jacob Joseph Slonim, Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Hebron. The mob called out that they would spare him because they knew him, but they demanded that he send out anyone who wasn't his family. He replied that everyone in his home was his family. So the mob killed everyone in the house. The only survivor was a three-year-old boy who hid beneath dead bodies. (You can see him in the collage above; he is the child in the upper left-hand corner.)

As I was reeling from this, Eliyahu added, "there's also another piece of the story." Some Muslims of Hebron chose instead to shelter and to save their Jewish neighbors and friends. (There is a brief section about that on the massacre's wikipedia page: Arabs shelter Jews.) Generations of Israeli children (and soldiers) have come to this museum to learn the history of Jews in Hebron, which culminates in this atrocity and then the British decision to expel all Jews from the city for their own safety, and then in Jews reclaiming this city and this land. The implication is clear: we lived here in peace, the Muslims attacked us out of nowhere, ergo they are fundamentally untrustworthy. "How might things be different," Eliyahu asked, "if there were another display, right here, about the Muslims who protected their Jewish friends?"

Two Hebron landscapes: city, and olive orchard.

We walked past a building which serves now as a yeshiva for religious Jews, called Yeshiva Shavei Hevron. Today it is home to some 300 young men who study purely for spiritual enrichment. Those who are learning there aren't seeking rabbinic ordination; this is Torah study lishma, "for its own sake." "If you're a Jew, you study Torah," Eliyahu explained. "It's central to who we are." That building is now under renovation to add a new dormitory floor. This is the only settlement construction within Hebron -- which according to the Israeli narrative isn't expansion. It's not increasing the Israeli footprint, since it's growing up rather than out.

A recently-repainted building, originally meant to be temporary, in Tel Rumeida / Admot Ishai.

From there we walked up to the hilltop Tel Rumeida -- also known as the Jewish neighborhood, or settlement, of Admot Ishai, established in 1984. (Its residents consider it a neighborhood and a legitimate Jewish habitation in a city where Jews have lived for centuries; they wouldn't call it a "settlement." Others, of course, disagree.) It consists of several small yellow-painted low buildings which were initially intended to be temporary; there is a small playground; there is an IDF military base; and there are exposed sections of an archaeological dig which reveal the original steps of the city of Hebron from about 4,000 years ago.

Archaeology of ancient Hebron.

We learned about the small community which lives on this hilltop. (Here's an article which tells some of that community's story in its own words: Tel Hevron-Admot Ishai.) And we learned a bit about the excavations and about ancient Hebron's history. Another reason why Hebron is one of Judaism's historical four holy cities: King David ruled in Hebron for seven years before moving his capitol to Jerusalem. Also, the ancestors of King David are understood to be buried there. We walked past an ancient olive orchard to reach the tomb of Ruth and Jesse (Yishai) -- Yishai being the ancestor of King David; Ruth being the ancestor of Yishai.

Tomb of Yishai and Ruth.

I stopped and said a silent prayer at that tomb, my hand pressed to the limestone. I feel a certain connection with Ruth, the intermarried outsider whose kindness and compassion to Boaz enabled his kindness and compassion to unfold in turn. From their (forbidden) marriage, our sages tell us, came a son who would one day be the ancestor of moshiach. Directly from that gravesite, one can climb a set of stairs to a rooftop outlook which looks out over the city and which I believe was part of the local IDF military base.

Me atop Tel Rumeida.

From there, a quick detour to see the small visible smidgen of a very ancient wall, even older than the original steps -- this is said to be the wall of enormous blocks which the scouts witnessed and, terrified of the giants who must have built it, retreated back to tell the other Israelites that they couldn't possibly conquer this land. (That story can be found in Torah in parashat Shlakh-Lekha.) Above this wall stands an olive orchard, and because that orchard is Palestinian-owned, no archaeological digging can take place there -- though it is believed that behind the wall, beneath the trees, are more remnants of ancient Hebron.

The very old wall.

Then down the hill to meet Mordechai, a young Orthodox rabbi who led us into the synagogue of Avraham Avinu, built in 1540. Mordechai was charismatic and pleasant to listen to; he is American-born, but moved to Hebron because the first time he visited there, as a post-college graduate interested in deeper Jewish learning, he felt immediately as though his soul had come home. He spoke repeatedly of the feeling that he and his community are there to serve a higher purpose and to access the elevated spiritual energy of this holy place.

Mordechai, our first guest speaker in H2.

People asked questions -- what's your life here like, what jobs do people have, that kind of thing -- and he gave fairly ordinary answers. One person asked whether, as rumor has it, settlers receive a stipend from the Israeli government in order to live there. "I wish it were so!" he chortled. "No, not at all." It's worth noting that he referred to this section of land as Judea and Samaria; I confirmed with him that these words are his signal that he believes the land was given to the Jewish people by God, and he said of course. "The term 'West Bank' has only existed since 1948," he pointed out, "when it was the west bank of Transjordan. The historical names are Judea and Samaria."

During the time when Hebron was under Jordanian control, the synagogue of Avraham Avinu was desecrated. One end became a public latrine; another end, a garbage dump; and in the middle, a sheep pen. The synagogue was rebuilt in 1981. Today it is once again a beautiful, clean, welcoming synagogue made of white stone with a domed roof and windows letting in the sunlight. And two original Torah scrolls which were saved have been restored to the aron kodesh -- we got to see them in their Sefardic standing cases; they are more than 300 years old, and they are beautiful.

The Torah scrolls of Avraham Avinu, now restored to their home.

Over the course of the morning we saw several monuments to people -- often women and children -- killed by Palestinian terrorist attacks. At each site, a house of study had been established in order to sanctify the memory of the deceased. For me the most horrible was the one commemorating the death of a one-year-old baby named Shalhevet Pass.

The last place that Eliyahu took us was to Ma'arat HaMachpelah, the building which stands over the Cave of Machpelah and the Tomb of the Patriarchs. According to the Torah, of course, Abraham purchased the Cave of Machpelah in order to bury his wife Sarah there. The building which stands atop that cave is around 2000 years old; it is built from the same Herodian stones which I recognize from the retaining wall which once held up the Temple Mount. During the 700 years of Muslim rule -- Mameluk, Ottoman, and Jordanian -- Jews (and Christians) were not permitted to enter that building. One outer wall was the closest Jews were allowed to come to the interior of the building, which is held sacred by both Jews and Muslims. We saw people praying there even now.

Eliyahu approaches the Herodian-era building over the cave; daveners outside the building.

We entered the building from the Jewish side. (The building is partitioned into a Jewish side and a Muslim side, and has been so ever since the Cave of the Patriarchs / Ibrahimi Mosque massacre.) We walked through a kollel, a place of study, where men were studying holy texts together. We walked past a small indoor/outdoor sanctuary.

The Jewish side of the building; a man in the small tent-covered sanctuary.

Eliyahu told us about the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre. He described Baruch Goldstein, the perpetrator, as an Army doctor whose futile efforts to save his friends after terror attacks caused him to lose his mind. "He was constantly living with the trauma of 1929," Eliyahu said. After the Purim day (during Ramadan) when Goldstein turned a machine gun on Muslims at prayer, killing 29 and wounding 175, the building was separated into two -- a Muslim part and a Jewish part. On ten days of the year, each group gets the whole structure to use as their prayer space. The rest of the time, it's divided. (Intriguingly, each side claims that the other group has access to more of the holy space -- and each side claims that the other has a "better" set of ten days as their own. Just a few more ways in which each side feels wronged by the other.)

For a small number of Jews, Eliyahu admitted, Goldstein is a hero; though most Jews would argue that what he did was unconscionable. His acts were immediately denounced by then-Prime-Minister Yitzchak Rabin and aso by Bibi Netanyahu, who was at the time the head of the Likud party. (In terms of more recent Diaspora response, Rabbi Arthur Waskow calls him Aror, "Cursed," rather than Baruch, "Blessed.")

Eliyahu told us the story of how the caves themselves (actually a cave-within-a-cave -- the name Machpelah means "doubled") was actually discovered beneath the building, and how there were indeed bones in the interior of the cave. Some photographs were taken, some maps were drawn, and then the caves were sealed permanently, because the site is too politically hot to be allowed to be accessible. And then, behind grilles and curtains, we saw the monuments to Abraham and Sarah and their descendants.

The tombs of Avraham and of Sarah.

Then Eliyahu turned us over to our second guide, a Palestinian man named Mohammed. Mohammed would take us through H1, the Palestinian side of Hebron, where Israelis are not permitted to go.

Our Palestinian guide, Mohammed.

Mohammed was both charming and impassioned. He took us directly to a Palestinian home where we were graciously welcomed for lunch. We sat on couches alongside low tables in a whitewashed room decorated only with calligraphy quotations (I assume from the Qur'an), and a man and his wife provided us with a delicious meal of noodle soup, chicken and rice, cucumber-tomato salad, hummous and pita. I regret that I have forgotten the man's name, though his wife was named Sahour. Their little girl Malak ("Angel") was one of the sweetest kids I've ever seen; she sat right next to me, I showed her photographs of my son on my phone, and she beamed at me. (Later I showed Sahour the same photographs and we smiled at each other, one mama to another.)

Our lunch feast.

From there we returned to the building over the Cave of Machpelah, this time from the Muslim side, to see the Al-Haram al-Ibrahimi, the Ibrahimi mosque. (Jews are technically not allowed into this prayer space; I neglected to mention that I am a Jew, and the IDF guards didn't ask.) A group of Israeli soldiers arrived on some kind of training tour, and rattan rugs had been laid down so that they could walk without taking off their boots. (Everyone else in the building had taken off their shoes, as is customary when entering Muslim holy space.) Mohammed fumed that this was a clear sign of their disrespect for Islam. One of the soldiers stopped to argue with him about it, but he was clearly not mollified. To him, the soldiers in their combat boots blithely walking into his holy space were just another microaggression in a lifetime of Israeli aggressions.

The mosque; soldiers visiting the mosque.

Our next stop was a rooftop where we met a Palestinian man who told us stories about his life there in the home which his family has inhabited for generations. To reach his roof, we climbed up a few flights of narrow curving stone stairs. Along the way I caught glimpses of people inside the house, and smelled food cooking, but did my best to keep my eyes on the stairs ahead of me both so I wouldn't fall and so that I wouldn't overly-invade this family's privacy.

Palestinian rooftop view.

Atop the roof, one of the men of the house told us about being arrested and imprisoned for three months for flying a Palestinian flag, and about his water tanks being ruined by settler bullets, and about how he doesn't bother to put a lock on his house because the soldiers will just break down the door when they want to come in and terrorize his children in the night.

Rooftop tank with bullet holes.

After a tour through the shuk (which was by and large similar to last time I was there, though I couldn't help noticing that both the merchandise and the shoppers were quite sparse, compared with other marketplaces I visited in Akko and Jerusalem) our last stop was a second Palestinian home. There we were welcomed by our second host, and we sat for a while in a comfortable living room draped with embroidered goods made by his wife. We drank hot tiny cups of cardamom-spiced coffee or mint tea, and ate green almonds which were distributed, with many giggles, by a three-and-a-half-year-old boy wearing a Spiderman shirt which my son would surely have coveted.

Second home visit. Alas, no photo of the kid in the Spiderman shirt.

Our second host told us a series of stories too. His first wife died when shot by settlers, and she was pregnant at the time. Today three of his four children are elsewhere for their own safety or health; only the little boy we met still lives with him, born to his second wife. He also told us that the window in the livingroom where we were sitting (which is abutted on all sides by Israeli-controlled real estate) had been barred from the outside by the army years ago, and that settlers had tried to kill his family by sending a poisonous viper into the room -- he showed us the snake in a jar. (The other things he said were things I could understand; the part about the snake was frankly bizarre.)

Remnants of tea, coffee, almonds.

After that the conversation shifted into a kind of general Q-and-A, in which people asked questions both of our host and of Mohammed. I remember hearing from Mohammed that he absolutely believes that the settlers receive government stipends for living in Hebron, and I remember hearing him say that the Palestinians just want to live in peace, to have equal rights, and to be allowed to move freely around the country, but the Israelis aren't interested in peace and will never agree to it. (I remember hearing similar things from the Palestinians who spoke to the group with which I came to Hebron in 2008.)

Mohammed talked about how checkpoints and Israeli policies of land control make it impossible for him to travel within his own country, and about how both sides need new political voices who aren't part of the old guard. And he talked about how he still has the key to his grandparents' pre-'48 house, and someday he dreams of living there again. I thought about asking what about the people who've lived there for the last 60 years and surely regard it as home too, but I didn't. I couldn't imagine that he would have an answer which would satisfy me, and my heart felt too bruised from facing this intractable conflict all day. (How's that for American privilege? But there it is.)

Modern Hebron.

He walked with us briefly into the edge of the newer city of Hebron, which had a completely different energy from what we'd seen before. It felt like any bustling Middle Eastern metropolis, alive and full of people and commerce and noise. (There we spotted a few Palestinian police; that is the part of town where Palestinian police are the local law enforcement, rather than the IDF.)

And then back to eerily-empty Shuhada Street with its closed-up storefronts. He bade us farewell at the second checkpoint there, because he's not allowed to cross over. "You can find me on Facebook," he joked, "just look for Mohammed."

Shuhada street graffiti: one protesting the ghost town, the other pro-Third-Temple.

Eliyahu met us there and we talked about the day and what our impressions were. And that's when Eliyahu said something I found really valuable: "In general," he said, "when it comes to the Jewish narrative, let the Jews tell the story of their experience; and when it comes to the Palestinian narrative, let the Palestinians tell their story."

Don't listen to the Palestinian narrative about the Jews, he advised -- for instance, there's that persistent Palestinian rumor that settlers receive government money for living in Hebron, which is not true. (Those with a low income may petition the government for welfare assistance, but that's provided to any Israeli, whether they live in Eilat, Tel Aviv, Haifa -- or Hebron. It's not a salary given for simply moving to contested territory.) By the same token, he noted, don't listen to the Jewish narrative about the Palestinians, which tends to be equally wrong. Instead, he urged, listen with compassion to each community tell its own story in its own voice.

It was only then that I discovered that the man in whose apartment we'd had coffee and almonds at the end of the day was the man from a recent news story I'd read before leaving the US. He'd put a Palestinian flag on his roof, and a settler (annoyed by its presence) came to remove it for him -- but got caught in the barbed wire between the Israeli-controlled buildings and his rooftop. So the Palestinian man helped the settler extricate himself, and then the army told him to remove the flag because in that location it was a provocation (although there are several Israeli flags on neighboring rooftops, which are apparently not considered provocative), and he did. (You can read all about it, and also see a few videos -- which feature our second Palestinian host, the man who had the flag on his roof -- here: Settler seeking to remove Palestinian flag in Hebron gets tangled in barbed wire, Jerusalem Post.)

Duelling propaganda 1: "Palestine never existed (and never will)."

Over the course of the day we saw Jewish posters arguing against the presence of Palestinians, and Palestinian posters arguing against the presence of Jews. It's clear that each side wants to delegitimize the other's claim to this place -- Jewish materials note that Hebron is only the fourth-holiest city in Islam while it's the second-holiest in Judaism; Palestinian materials argue that Jews have no historical connection to the land; and so on.

Duelling propaganda 2: "Warning! this is illegally occupied land."

The mistrust and misunderstanding on each side is phenomenal. Eliyahu mentioned that even today, his Jewish colleagues ask how he can trust the Palestinian guides with whom this tour collaborates. Mohammed described settlers as "crazy" and told us that they are all armed and dangerous, and it was clear that he regarded most Israelis as untrustworthy. I'm pretty sure that Eliyahu thinks we need to find a different paradigm, one in which each side acknowledges the other's connections to and love of this land. I do, too. But I don't have any idea how that's going to happen.

I came away from the day feeling overwhelmed and sad, my mind abuzz and charged-up from all of the stories we'd heard, my heart weary and drained. Hearing about the murderous pogrom of 1929, or the anti-Jewish suicide bombings of recent decades, makes me want to cry, or throw up, or possibly both. And then on the other side the stories of pregnant Palestinian women killed by settler gunfire, or Palestinian children traumatized by late-night IDF incursions, give me the same kind of emotional reaction. (For more datapoints, look at this list of incidents in Hebron.) In one set of stories, Jews are the victims. In the other set of stories, Jews are the perpetrators. The cognitive dissonance makes my head spin.

The hardest thing for me is that I can't see how things are going to get better. Of course, one could argue that the very fact of this dual narratives tour is a sign of hope. The fact that Jerusalem Peacemakers teamed up with this Palestinian NGO and with Abraham Tours to make this happen, and the fact that a group goes twice a week and the tour seems always to be full, is a sign of hope. The fact that people are trying to meet each other, however clumsily and cautiously, is a sign of hope. But these are small signs of hope taken against the backdrop of a deeply-entrenched history of enmity and mistrust.

More duelling signage.

On the bus back to Jerusalem I heard Eliyahu talking with another person who'd been on the tour, and I heard him saying that just as our conflicting religious stories often fuel the violence, those same religious stories can fuel our reconciliation. (That's the kind of answer I associate with Rabbi Menachem Froman, may his memory be a blessing.) I hope that he is right, and that our religious traditions -- including the one which I so deeply love, and in which I have dedicated my life to serve -- can help to heal these wounds. But I don't know where to go from here.

I'm glad I went on this dual narratives tour; I absolutely recommend it. But as one of my fellow passengers said on the bus back to Jerusalem, "I feel like I have more questions now than I did before we started." I think that's a sign that the tour did its job, but sitting with these tensions is hard. And I'm always aware that I'm generally coming to this from the comfortable perspective of the Diaspora. I live half a world away. My confusion and grief matter to me because I'm marinating in them, and because as a rabbi and a Jew I feel connected with these stories in complicated ways, but my feelings and reactions are nowhere near as important as the suffering and anger of those who live with these realities every day.

If you would like to see more photos, here's the photoset from this daytrip: Dual Narratives Trip to Hebron. (And here's my photoset from the other parts of my trip: Israel 2014.)

Also worth reading:

In the Land of Double Narrative, a Tikkun article by Mimi Schwarz about Hebron.

Day Trip to Hebron Photoessay by Adam Groffman, which chronicles the same dual narratives trip I took, though with a few different features.

March 30, 2014

A Shabbat evening with the Nava Tehila community

At my first Jewish Renewal Shabbat services, back at the old Elat Chayyim in 2002, I felt as though my soul had come home. Every time I have davened with Nava Tehila, the Jewish Renewal community of Jerusalem, I have felt the same way.

When I saw that Nava Tehila didn't have a scheduled service during my time in Israel, I shrugged and figured that was just the luck of the draw. They only meet once a month; I was only here for ten days; it was okay. I made plans to spend Friday evening with Bill and Trudianne, two Jewish Renewal friends from Edmonton, whom I met at the Reb Zalman retreat at Elat Chayyim in 2004. I figured we'd come up with someplace to daven one way or another.

But then on Thursday night at my poetry reading (sponsored by Nava Tehila, and hosted in the home of a Nava Tehila member) I learned that the community would be having a service after all. It wasn't an official open-to-the-public service led by Reb Ruth and her band of amazing musicians; rather, a community service, led by community members, hosted in a community member's home. They were gracious enough to welcome us into their midst for the night, and it was exactly what my heart needed.

As the musicians began to play, people lit candles, and I went to kindle two tealights myself. As I lit them, I was overwhelmed by a wave of emotion -- thinking of my usual weekly tradition of lighting Shabbat candles with our son while Skyping with my parents 2000 miles away. I have had an amazing time in Israel, and will be enriched by this trip for a long time to come -- but I also really miss our little boy, and lighting candles without him made me a little bit weepy.

We sat in a circle in a gracious apartment with a big and beautiful mirpesset (balcony) from which one can see the Mount of Olives, the panorama of the Jerusalem foothills, and apparently on clear nights one can see the lights of Amman in the distance across the Dead Sea. There were several guitarists, one person playing a small harp, and one drummer. We moved through the psalms of kabbalat Shabbat, the service of welcoming the Shabbat bride, without any commentary or page numbers (or for that matter, siddurim) -- people just knew the words.

Many of the melodies were melodies I know from previous encounters with Nava Tehila, or from their two beautiful cds. (You can hear their music at Bandcamp.) Spontaneous harmonies unfolded. We sang with gusto. The musicians were terrific: all in synch with each other, changing tempo and mood effortlessly. At the best moments it felt as though we were all part of one organism, one heart with many bodies and voices giving voice to our shared Shabbat prayer.

When we went out on the mirpesset to welcome the Shabbat bride, I found myself overcome by emotion again. Grateful to be here -- grateful to be ringing in Shabbat with a room full of people who know what these words mean and who love them as much as I do -- amazed to be singing these ancient psalms, and these medieval Shabbat hymns, here, in this place, Jerusalem -- awestruck to be davening outdoors, looking over these hills which are at once so parallel to, and so wildly different from, the hills on which our deck looks out at home -- filled with yearning: for home, for here, for the healed and whole Jerusalem of my dreams, for my family (and especially our son), for connection with Shabbat...

And then someone I didn't know placed a kind hand on my arm, and I thanked her silently, and I pulled myself together and let the tears recede, and joined the singing again.

At one point, when we had paused for a moment, we heard the adhān ringing out from minaret after minaret. "God is great," someone murmured. "They're singing harmony with us," someone else said. A moment later came the riotous ringing of Friday evening church bells.

After an hour of luxurious kabbalat Shabbat singing, we heard a d'var Torah from a community member (usually given in Hebrew; tonight, in deference to the many visitors, he spoke mostly in English) and then another community member led us in a short-and-sweet ma'ariv (evening) service. We blessed juice and challah, enjoyed a glorious potluck (my contribution was the fresh strawberries I'd bought in the Old City that afternoon), and then spent some time in triads talking about how we're feeling spiritually as Pesach approaches. My trio sat on the mirpesset, and as we talked, we stopped to marvel at the fireworks down in the valley -- an Arab wedding, my hosts explained.

When we regrouped we sang some spontaneous niggunim -- more close harmonies, more deep feeling -- and then Bill and Trudianne and I regretfully bid the group farewell and caught a cab back to the Old City.

Before I left, I was honored with the request to share a poem. (I read this week's Torah poem from 70 faces, "Like God.") Before I read the poem, I thanked them for welcoming me. I said that every American rabbi comes to Jerusalem hoping for spiritual sustenance, for that feeling of one's soul being revitalized and rejuvenated -- and that I'm not sure everyone actually has that experience, even though it's what we come here for -- and that davening with Nava Tehila gives me exactly that: it fills me up and renews me to return home and bring these living waters back to the community I'm blessed to serve.

March 29, 2014

An unexpected messenger

I walked to Ben Yehuda street toward the end of Shabbat, thinking that I was going to wait on a park bench until Shabbat ended and the stores opened, in order to try to buy a Spiderman kippah for our son. (I should've just bought one in Tzfat when I first saw them; I haven't been able to find one anywhere else!) I did stay on a park bench for quite a while, and waited until well after nightfall, and the kippah stores did not open, and finally I walked back to the Old City and treated myself to one last Jerusalem dinner (kubbeh, pita and hummous, salatim, and a slushy mint-flecked lemonade -- glorious.)

But I did have an encounter on Ben Yehuda which may have been the real reason that I was there.

I was sitting on the park bench, thinking about my trip, thinking about home, when a man in a dark suit wearing a black hat stopped to ask me something in Hebrew. I answered, he thanked me, he moved on. A few minutes later, he was back. And he asked if he could talk with me. I was initially a bit reluctant, but there was something about him which felt safe to me, so I acquiesced. He said (in Hebrew) that he sensed that I was sad, and that his heart felt a connection to me, and that he wanted to urge me to cultivate joy. This sounds corny, doesn't it? But my instincts told me that this guy was okay, and I am never one to turn down a spontaneous spiritual encounter.

He asked if I pray, and I said that I do indeed. Then he asked if he could recite a psalm for me or with me. I suggested psalm 126, which I know by heart, and we recited it together. There was something extraordinary about saying those words -- that ancient psalmist's expression of joy at returning to Zion -- in this place. Then he offered psalm 122, and we prayed that one together, too. "I lift my eyes up to the mountains. From where comes my help? My help comes from the Holy Blessed One, creator of heaven and earth!" It's another one of my favorites.

He asked if I would tell him what had been on my mind. I said that I was thinking about my son, who is far away. He told me about his eight children and grandchildren, and about his son Noam who was born with encephalitis -- "water on the brain" -- who died fifteen months ago at the age of twenty. I offered him the traditional words of consolation, and he clasped my hands and blessed me. He told me about the nonprofit he now runs, which provides free meals for the poor, and which is named in his son's memory, that the merit from the good deed might accrue on his son's behalf.

We smiled at each other. He told me that he is an Orthodox rabbi named Yitzchak; I told him that my name is Rachel, and he called me his sister. He expressed some surprise at my Hebrew and my fluency with the psalms, and asked what I do. I told him that I am a poet and a mother -- a partial truth; I didn't have the sense, in that moment, that he would respond well to hearing that I am a rabbi, so I left that part out. He blessed me that I should have joy in my writing and joy in my son. "Teach your son to love everyone," he advised me, solemnly. "That is the most important thing." He blessed me again, and I thanked him from the bottom of my heart.

So I didn't get the kippah I was hoping to find. But I did get a blessing -- several blessings, really. Perhaps the friendly man in the black hat was an angel, a messenger, stopping in to remind me to serve God with love and with joy.

Meeting new (old) friends

One of the joys of being a longtime blogger is having the chance to meet people whose words one has read for years. I've had the opportunity to meet three bloggers while I've been in Jerusalem. First I had lunch with Chaviva (of Just Call Me Chaviva); then Ilene (of Primagravida) hosted me for a poetry reading; and then I spent most of a day with Vicky (of Bethlehem Blogger.)

On Thursday Chaviva and I met for lunch on Emek Refaim in West Jerusalem, where we chatted about life, parenthood (her baby is adorable), how I came to the rabbinate, how she came to Israel, how Israel has and hasn't been what she imagined before she made aliyah, what it's like living far away from family, and so on. Chaviva lives in Neve Daniel, which I had seen briefly from the bus on my way home from Hebron the day before. It is lovely and green and looks like a great place to rear a kid. (Of course, to its residents it is a suburb of Jerusalem; to the residents of Bethlehem just down the hill, it is an illegal settlement. I did mention that I'm trying to sit with the contradictions, right?) I didn't think to snap a photo, so you'll just have to take my word for our encounter.

The poetry reading, moderated by Ilene and hosted by a lovely woman named Rachel in her Baka apartment, was wonderful. I read poems from both 70 faces and Waiting to Unfold, and talked about Torah and parenthood and poetry and postpartum depression and all kinds of good things. It was such a sweet evening that I almost missed my guesthouse's curfew!

And then the next day Vicky came to meet me at the guesthouse for spiritual pilgrims where I have been staying in the Old City. She took me to a fantastic bookstore-café in East Jerusalem where we ate sandwiches and chocolate cake, and browsed books, and talked about all sorts of things -- how she came to Bethlehem, her PhD research, the children with whom she works, how and why I became a rabbi, culture, theology, her Bethlehem host family, and more. It was the sort of meeting where one instantly feels as though one is with a longtime friend. Of course, we've been reading each others' blogs for years, so we have known each other for a long time, even if we hadn't met in person before. But I suspect that our blog-familiarity is only part of why we clicked so comfortably.

St. Peter in Gallicantu.

Then she took me to see one of her favorite places in Jerusalem, an utterly spectacular church on the far side of the Old City. It's called St. Peter in Gallicantu, and the name denotes the cock crowing -- as in the story of Peter rejecting Jesus three times before the rooster could announce the morning. I didn't manage to get any great photographs of it, so the one above will have to stand in. The interior mosaics which cover the dome and its pillars are incredible: a soft rainbow of colors, a ring of angels bearing trumpets whose robes resemble clouds. And although there was a tour group there when we arrived, we sat quietly off to the side and in time they departed and left us alone in the basilica, which was quiet and peaceful in a way I rarely associate with this city! The church was serene and I said a silent prayer that real peace may come speedily and soon to this place where so many people for so many centuries have sought connection with God.

With Vicky, post-falafel.

She came with me back to my guesthouse so I could don a clean white shirt for Shabbat. We had glorious falafel near the Damascus Gate, and she taught me how to say strawberries in Arabic (so I could buy some for the Shabbat potluck I would be attending), and then we regretfully parted ways. Vicky wrote a really lovely post about our day together: Meeting the Velveteen Rabbi.

I'm grateful that the internet has brought me into connection with so many wonderful people here.

March 26, 2014

The adventure of staying somewhere new

View from the roof of the Ecce Homo, twilight. Below: intersection with minaret, shopkeeper's wares.

I've never stayed in the Old City before. The moment I walk out of the convent guesthouse where I am staying, I'm on the cobblestones of the Via Dolorosa. Merchants selling Christian religious icons beckon me into their storefronts. If I continue walking away from the Lion's Gate, I reach a T-junction. If I turn left there, and follow the road as it zigs and zags a bit, I wind up at the Kotel. If I turn right, and follow the road as it zigs and zags a bit, I wind up at the Damascus Gate.

I've never stayed in the Old City before. The moment I walk out of the convent guesthouse where I am staying, I'm on the cobblestones of the Via Dolorosa. Merchants selling Christian religious icons beckon me into their storefronts. If I continue walking away from the Lion's Gate, I reach a T-junction. If I turn left there, and follow the road as it zigs and zags a bit, I wind up at the Kotel. If I turn right, and follow the road as it zigs and zags a bit, I wind up at the Damascus Gate.

I don't think these streets are officially part of the marketplace (shuk in Hebrew, souq in Arabic), but there are market stalls along them nonetheless. A few vendors are selling prayer beads / rosaries (both Christian and Muslim), or religious icons. Others sell leather sandals, spices, Arabic candy, loops of sesame-encrusted bread, plastic toys, abayas, and alarm clocks shaped like the Dome of the Rock.

I am an obvious outsider in my jeans, sandals, and t-shirt. Even when I don't have my camera out, even without a guidebook in hand, I am clearly a foreigner, which means that vendors call out to me as I pass. "Hello! Miss! Step inside. Come and see." I smile but keep on walking; I'm not in the market for their wares. I wish I could snap photographs of the market stalls, and of the locals as they weave effortlessly through the foot traffic, but I don't.

Breathing in, I inhale coffee with cardamom, a tendril of the incense burning at the spice vendor's shop, vehicle exhaust, the apple-like sweetness of nargila smoke. The scents link me instantly with my summer in Jerusalem and with the trip Ethan and I took to Amman. This is the fragrance of the Middle East. I wonder whether I first encountered it on my adolescent trip to Cairo with my parents and sister, all those years ago, but I can't call up those sense-memories. One way or another, there is nothing like this scent back home.

Around me I hear the clamor of voices, mostly speaking Arabic, which I do not understand. Occasionally I hear a snatch of Hebrew, mostly from the visibly-Jewish passers-by, the men in black frock coats with peyos and hats, the women with their hair wrapped in scarves who push strollers and lead little ones by the hand. The streets are narrow; there is barely enough room for the occasional car which creeps through, horn blaring when the foot traffic gets in its way.

Around me I hear the clamor of voices, mostly speaking Arabic, which I do not understand. Occasionally I hear a snatch of Hebrew, mostly from the visibly-Jewish passers-by, the men in black frock coats with peyos and hats, the women with their hair wrapped in scarves who push strollers and lead little ones by the hand. The streets are narrow; there is barely enough room for the occasional car which creeps through, horn blaring when the foot traffic gets in its way.

As I return to the guesthouse, the set hour arrives for Muslim evening prayer. The adhān rings out first from one minaret, then from another, and within moments I am ensconced in an aural web of voices coming from every direction. The melody is plaintive and melancholy to my untrained ear. (Not so much a melody as a nusach -- like the old melodic modes in which we sing weekday prayer.) The voices seem to ripple, like the surface of a pond into which stones have been thrown. When the call to prayer falls silent, I hear the sound of church bells.

Photos, once again, from my ever-expanding trip photoset.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers