Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 171

December 17, 2013

Two versions of a short winter poem

Snow drops a scrim over the lake,

softens every outline.

The roads become sepia-tone

caked with dirt and salt.

Behind glass, a small white cat

watches flutters of grey and black

juncos and chickadees

at their perennial cocktail party.

EIGHT LINES OF WINTER, II

Snow drops a clouded scrim,

softens every outline.

The roads become sepia-tone.

Snow drops a clouded scrim

on flutters of grey and black

at their perennial cocktail party.

Snow drops. A clouded scrim

softens every outline.

I haven't posted a new poem here in a while. As part of an ongoing effort to be better at self-care (not always the easiest thing for mothers or for clergy), I'm trying to take Tuesdays as self-care days -- which for me often means poetry-writing days.

I have two versions of this one on my desk right now. I can't decide which I prefer. The first has more specifics ("caked with dirt and salt," "juncos and chickadees.") The second works with a known poetic form (the triolet, though mine has neither rhyme nor meter.) Do you like one better than the other?

Image source: my flickr stream.

December 15, 2013

Returning to the hospital which saved my life

I don't remember when I first learned the story of my birth. As long as I can remember, I've known that I was born ten weeks early, weighing 3 lbs 1 oz, in a hospital which had no neonatal unit; that I was rushed across town in an ambulance and lost half of my birth weight before I made it to the neonatal unit at Santa Rosa; that I spent six weeks in an incubator because I had hyaline membrane disease, a terrifying diagnosis because it had recently taken the life of Patrick Bouvier Kennedy.

I don't remember when I first learned the story of my birth. As long as I can remember, I've known that I was born ten weeks early, weighing 3 lbs 1 oz, in a hospital which had no neonatal unit; that I was rushed across town in an ambulance and lost half of my birth weight before I made it to the neonatal unit at Santa Rosa; that I spent six weeks in an incubator because I had hyaline membrane disease, a terrifying diagnosis because it had recently taken the life of Patrick Bouvier Kennedy.

I knew in a distant intellectual way that many premature babies born as early as I was didn't survive. I remember taking penicillin every day until I was about six, when suddenly tests showed that I had developed surfactant, to everyone's surprise. (Developmental insufficiency of surfactant, and underdeveloped lungs, are among the problems of hyaline membrane disease, now called infant respiratory distress syndrome.) But as a kid I took my own survival for granted, as I think most children do.

It wasn't until my nine months of clinical pastoral education, in my first year of rabbinic school, that I started to understand just how scary my birth must have been for my parents. One of the places where I made the rounds, at the hospital where I served as a student chaplain, was the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). There I saw impossibly tiny babies, babies whom one could hold (as my father had always reminisced) in the palms of cupped hands. Babies struggling for vitality. And I saw their parents, by their sides, hoping and praying and yearning for their babies to thrive until they were healthy enough to bring home. When I could, I ministered to those parents. Sometimes I told them that I myself had been one of those NICU babies. I think -- I hope -- that they took some comfort from that.

While I was in San Antonio visiting family last week, my childhood pediatrician took me to visit the NICU at the hospital which saved my life. As a kid I knew Dr. Wayne as the tall man with the gentle voice who took care of me when I was sick (which was fairly frequent -- perhaps a legacy of my premature birth.) He used to give me tongue depressors on which I could draw puppets. Now I know that since then he's had a broad and illustrious career which includes teaching medical students, serving as an administrator for Christus Santa Rosa Children's Hospital, and being honored there with the creation of the Richard S. Wayne Distinguished Chair for Pediatric Cardiology. And he was gracious enough to take the time to give me a tour of the NICU which once saved my life.

Dr. Wayne began by showing me photographs from the early days of the hospital, starting with the three Catholic Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word who began caring for the sick there in 1859. (My favorite photos were from the 1920s: the doctors with bushy mustaches and white coats, the nuns standing in the background of the operating room in their dark habits, and of course no one was gloved or masked because that wasn't yet the norm.)

Dr. Wayne began by showing me photographs from the early days of the hospital, starting with the three Catholic Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word who began caring for the sick there in 1859. (My favorite photos were from the 1920s: the doctors with bushy mustaches and white coats, the nuns standing in the background of the operating room in their dark habits, and of course no one was gloved or masked because that wasn't yet the norm.)

Then we went to the place which had been the NICU in 1975 -- a small squarish room, now a storage room filled with disused hospital beds. (On some walls, remnants of yellow duckling wallpaper remain, a faded imprint of the room's former life.) He showed me where the neonatal cribs had been. I could see how little space had been available for anyone else in the room; parents couldn't stay with their kids, there was no place for them to be. He told me about what they had at their disposal back then, much of it retrofitted adult medical equipment.

And then he showed me today's NICU at Santa Rosa, with its brightly-colored floor cemicircles denoting each two-crib "pod," the headwalls filled with places to plug in monitors and medicine-dispensing pumps, gentle lighting for the babies' comfort, floors and ceilings designed to mute the busy hospital's sounds. To my amazement, we met someone on the neonatal transport team who's been working there for 41 years, and when told my birth year and situation, remembered me! We walked slowly around the unit, and as we passed different babies, Dr. Wayne stopped to chat with their caregivers or to remark quietly to me about some detail of their situation and their care.

Visiting the modern NICU moved me deeply. I saw tiny babies: some resting in their specialized cribs; some cradled in nurses' arms, in the wooden gliding rockers which sit alongside each crib, taking bottles; some attached to specialized preemie ventilators. Dr. Wayne showed me some of the equipment they use in truly dire cases, including cases where they have to mechanically bypass both heart and lungs. (That's extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, and the Santa Rosa NICU is one of the places where this procedure is done with neonates.) We visited the pediatric intensive care unit, too (where I thought, with quiet grief, of Superman Sam and his family as they move into hospice mode). Everywhere we visited, I was struck, as always, by the kind and gentle caring of the pediatric nursing staff.

When I was a student chaplain, I was married but had not yet taken the leap into parenthood. My chaplaincy colleagues told me that having a child would be a profound theological education. And they were right. Many of the poems in Waiting to Unfold reflect how becoming a mother has changed my sense of God. As I toured the NICU and PICU at Santa Rosa, I found myself thinking not only about God's limitless compassion, but also God's limitless grief when Her children suffer. I suspect that ministering to pediatric patients and their families would challenge me in a new way now that we have a child. It would be all too easy to project my own fears of loss and grief onto the parents and children in need of care.

The modern NICU at Santa Rosa is gorgeous -- and as the hospital is reconstructed in its new form, it's going to be replaced by a new NICU which will be light years ahead of this one, as this one was light years ahead of the one I once inhabited. (For more: see Children’s Hospital of San Antonio to work with Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital to elevate pediatric care in San Antonio, about Santa Rosa's plans to collaborate on a new facility.) But before that renovation takes place, I'm grateful for the opportunity to walk through these halls and to offer silent prayers for healing for the babies who are growing there now -- and to offer my spoken words of immeasurable gratitude to those who every day do the work of keeping kids like me alive.

Black and white image: NICU "isolette" from 1984, nine years after my NICU years, from a history of the March of Dimes. Second image: from an Express-News article about the Santa Rosa NICU.

December 11, 2013

This week's portion: deathbed blessings, deathbed curses

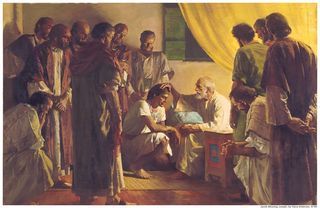

In this week's portion, Vayechi, we begin with the death of Jacob and end with the death of Joseph. Jacob blesses Joseph's sons with sweet words, and then he offers parting words to all of his own sons. Some of those parting words are more like curses than like blessings. What must it have been like to be one of the sons who received stinging rebuke from his dying father?

In this week's portion, Vayechi, we begin with the death of Jacob and end with the death of Joseph. Jacob blesses Joseph's sons with sweet words, and then he offers parting words to all of his own sons. Some of those parting words are more like curses than like blessings. What must it have been like to be one of the sons who received stinging rebuke from his dying father?

I'm reminded of my beloved grandfather who became sometimes anxious and paranoid as he neared death. He could easily become convinced of terrible things (for instance, that another family member was making a pass at his wife) and at this times he made accusations which we all knew weren't true.

When those episodes arose, all we could do was gently try to reassure him that he was mistaken, and shower him with love, and forgive him the things he had said. We knew that the man he had been when he was fully alert would never have said those things. No one held those moments against him. I've seen this with others, as well. A woman grows old and begins to lose track of things and, frantic, accuses her daughters of stealing her silver. Or her caregivers. Or a spouse who is long-gone...

When Jacob spoke harshly to some of his sons as he lay dying, was he fully aware that these would be his last words to them -- that this anger was what they would remember of their father when he was gone? Were his assessments of his sons accurate, in that moment of extremis? (For instance, his accusation that Reuven had "mounted his bed," which is to say, had made a pass at Jacob's wife?) Granted, some of the sons may have deserved his harshness -- I'm thinking of Simeon and Levi, who chose to slaughter the entire tribe of Shechem in the story of Dinah. But even if the angry words were deserved, was this really the time to speak them? I wonder what was the impact of these words on those men as their father prepared to die.

Reading Vayechi this year, I wonder what it would take for us to forgive Jacob / Israel for his flaws and his errors. He played favorites with his sons, as his father and grandfather had done before him. And given the opportunity to say goodbye to his sons and to give all of them a final blessing, words of hope for the lives they may yet lead, he doesn't speak with compassion to all of his sons. How might it change this story for us if we imagine Jacob, at that moment, as not-entirely-tethered to reality -- like those we have known who have been prone to flights of paranoia in their elder years? How might we change our own stories of how we relate to those we love who are dying -- and how we relate to those we love when it is our time to say goodbye?

I initially posted this alongside a request for help in figuring out who had painted this illustration. Thanks to Barbara and to Sam Steinmann, both of whom left comments / emailed me indicating that the artist is Harry Anderson, a member of the Mormon community.

Other years' commentary on Parashat Vayechi:

2007: Carrying our bones (originally published at Radical Torah)

2009: Instead of sons [Torah poem]

2010: The blessings of Ephraim and Menashe

2012: For a reason [Torah poem]

December 8, 2013

Making God present: protecting human rights

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for Human Rights Shabbat / parashat Vayigash, crossposted to my From the Rabbi blog.

Today we're observing Human Rights Shabbat. Human rights are woven into the fabric of our tradition. They've been there from the very beginning, the creation of humanity in the image and the likeness of God. Every human being bears God's DNA, as it were; each of us reflects a unique facet of divine infinity.

Because every human being is a reflection of God, containing a spark of divinity within, every human being has inalienable human rights regardless of race, gender, creed. The right to worship freely, without coercion. The right to pursue meaningful work. The right to earn a living wage. The right to choose the shape of one's family. The right to be treated as a whole and holy creation of God.

Over recent weeks our Torah portions have taken us into the Joseph novella. Joseph's story features several suspensions of his human rights: when his brothers throw him into the pit, when he's sold into slavery, and when he's cast into Pharaoh's jails.

In Joseph's story, of course, everything happens for a reason. Joseph himself is certain of this. When he reconnects with his brothers he assures them, "don't feel guilty for what you did -- even if you intended it for ill, God intended it for good." The Joseph story is a classic example of what our tradition calls "descent for the sake of ascent." In order to be lifted up, you have to recognize that you're someplace low.

Here's someplace low: our world is marred by human rights violations which ignore the innate wholeness and holiness of every human being.

Some of these happen far away, and we may feel we can safely ignore them: children mining mica in India to bring sparkle to American womens' makeup, or Chinese workers laboring 21-hour days in a soccer ball factory. [Source: slaveryfootprint.org] Others are closer to home: indefinite detention and torture at Guantanamo Bay; an American prison system disproportionately filled with young men of color; rampant prejudice against immigrants and against Muslims.

Later in our Torah story, a Pharaoh will come who does not remember Joseph, and he will be alarmed by the Hebrews resident in Egypt. Torah says "the Israelites were fruitful and they swarmed;" perhaps that word 'swarmed' is meant to suggest how that Pharaoh saw us. Pharaoh whips his people's anxieties into a lather, and -- spurred by those anxieties -- the Egyptian people become merciless taskmasters. They're capable of treating their recent neighbors inhumanely because they have come to see the Hebrews as subhuman.

After all, those Hebrews swarm like bugs. "You know those people, they're not like us, they dress funny, they eat strange foods, they have so many children, they're going to overrun our country, who let those people in, they're mooching off of our government's generosity, it's not our job to support them, they should be deported back where they came from..." People say those things today, too.

The International Declaration of Human Rights reminds us that "Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay." Rest and leisure: the gift of Shabbat, a day for nurturing and nourishing body, heart, mind, and soul. This is precisely what was denied to our ancestors in Mitzrayim.

This gift of rest -- built by God into the fabric of creation -- is also denied to those today who live in poverty. If you have to work several jobs just to get by, you can't be home to take care of your kids -- which in turn means that those kids grow up not only fiscally struggling but parentless, and therefore statistically likelier to wind up in trouble. It's our job to work to change that system.

Another article of that declaration says, "No one should be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment." The ancient Egyptians, Torah tells us, made our ancestors' lives bitter with hard work. Then they systematically killed Israelite newborn boys. A number of midrashic sources tell even more horrible tales.

Equally dreadful things happen today in prisons around the world, including some for which our government is responsible. And there are other governments which receive US military assistance even though they routinely engage in torture. [Source: National Religious Coalition Against Torture.] It's our job to argue against this: to agitate for treating everyone humanely -- even enemies, even prisoners, even prisoners of war, here and everywhere.

In the Joseph story, every descent happens in order for the next ascent to be greater. It's our job to take every place where our world is low, and work to turn it around into an ascent.

This Shabbat we join the world in mourning the death of Nelson Mandela, who fought against the horrors of apartheid, was imprisoned for 27 years, and emerged to lead his beloved South Africa into a new era of reconciliation and justice. He was a champion of human rights and a beacon of hope. His life took him lower even than Joseph...and he emerged to extraordinary heights. His memory is a blessing. May it impel us to rededicate ourselves to seeking full rights for every human being on this earth.

Scholar Judy Klitsner notes that once we enter into the Biblical story of Egypt's dehumanization of the children of Israel, there are no mentions of God. When we dehumanize others, then God recedes; God disappears from our story, from our world, from our lives. And when we make the positive choice to remember that every person is made in the image of God, then God becomes present for us again. When we work for human rights, we make God more present in the world. Kein yehi ratzon: may it be so, speedily and soon.

December 7, 2013

A prayer before departing this life

On my first day of hospital chaplaincy training, I was surprised to discover that one needn't be Christian in order to baptize a baby. One need only say the words with intention.

On my first day of hospital chaplaincy training, I was surprised to discover that one needn't be Christian in order to baptize a baby. One need only say the words with intention.

Those of us in my chaplaincy cohort who were Jewish, or Muslim, or came from traditions which don't do infant baptism, had a lot of conversations that year about how we might handle that situation if it came up. Our hospital's policy was that we only provided baptism in cases of extremis, for babies who were near death or too ill to leave the hospital and be baptized in their home community. (My plan was that I would ask the parents if they wanted to say the words, since as Christians they would find the words more meaningful than I, and I would seek to sanctify the moment with my presence.) Though I thought about it and planned for it, I was never called-upon to serve in that way.

But I did have many experiences with those who were dying. On my first day, when I learned that fascinating tidbit about baptism, I also learned that the Catholic sacrament of the sick -- formerly known as "last rites" -- does require a priest. If a Catholic patient were near dying, we were instructed to call the priest on call and get him in there. During the day, there was usually a priest in the hospital with us; overnight, the on-call priest would be elsewhere, though would come if we paged him. I remember one of the hospital's on-call priests teasing us that if we woke him at 2am for someone who turned out to survive until dawn, he was going to be very miffed at us for ruining his sleep. (He was kidding.) And I remember times when I had to call him in the middle of the night. That was the year I began learning about Jewish customs having to do with sickness and death. I'm pretty sure it's when I first encountered the deathbed vidui.

I've written about different forms of the vidui before. "Vidui" means "confessional prayer," and it comes in several forms. There's one version of it intended for daily use, which really speaks to me, and which I try to say every night before bed. There's another kind of vidui which we say on Yom Kippur. And then there's the one which the tradition instructs us to recite before death. Though there's nothing wrong with saying it at a different time. If needed, the prayer can be recited more than once. There's no superstition attached to it, it's not as though saying it "too soon" will somehow bring death sooner, there's nothing wrong with saying it and then surviving and getting to say it again another day. What the tradition teaches is, when death is imminent (whatever that means to you), it's appropriate for the ill person (or someone else on his/her behalf) to offer a vidui. Here's the version of that prayer which is found in the Reform Rabbi's Manual:

Deathbed Vidui

My God and God of all who have gone before me, Author of life and death, I turn to You in trust. Although I pray for life and health, I know that I am mortal. If my life must soon come to an end, let me die, I pray, at peace.

If only my hands were clean and my heart pure! I confess that I have committed sins and left much undone, yet I know also the good that I did or tried to do. May my acts of goodness give meaning to my life, and may my errors be forgiven.

Protector of the bereaved and the helpless, watch over my loved ones. Into Your hand I commit my spirit; redeem it, O God of mercy and truth.

יְיָ מֶֽלֶךְ, יְיָ מַלַך, יְיָ יִמְלֹך לְעוֹלָם וַעֵד / Adonai melech Adonai malach Adonai yimloch l’olam va’ed.

(God reigns; God has reigned; God will reign forever and ever.)

בָּרוּךְ שֵׁם כְּבוֹד מַלְכוּתוֹ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד. / Baruch shem k’vod malchuto l’olam va’ed.

(Blessed be God’s name whose glorious dominion is forever.)

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל, יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְיָ אֶחָֽד: Shema Yisrael Adonai eloheinu Adonai echad.

(Hear, O Israel: Adonai is our God, Adonai is One.)

Here is an alternative vidui prayer -- one which speaks in slightly more Jewish Renewal language:

Alternative Deathbed Vidui

I acknowledge before the Source of All that life and death are not in my hands. Just as I did not choose to be born, so I do not choose to die.

May my life be a healing memory for those who knew me.

May my loved ones think well of me, and may my memory bring them joy. From all those I may have hurt, I ask forgiveness.

To all who have hurt me, I grant forgiveness.

As a wave returns to the ocean, so I return to the Source from which I came.

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל, יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְיָ אֶחָֽד: Shema Yisrael Adonai eloheinu Adonai echad.

(Hear, O Israel: Adonai is our God, Adonai is One.)

As I learned in my "From Aging to Sage-ing" class in rabbinic school, it's also possible to write one's own deathbed vidui, to recite in addition to the traditional one. (You can find many other variations, as well as some beautiful deathbed practices and prayers, at Alison Jordan's website Vidui Variations -- a website which I find deeply valuable and which I higly recommend.) And I've formed the practice in my rabbinate that if no vidui was recited before death by the person who has died, or by someone else in that moment on their behalf, I will sometimes recite one on behalf of that person's soul at the funeral, before interment. I think healing is often possible for those who are present when they hear this intention of letting go of grudges and seeking forgiveness for the places where one has missed the mark.

I frequently teach about the tradition which says that one should make teshuvah -- repent; atone, return to God -- the night before one's death. Of course, who among us knows when that night is coming? Therefore our tradition teaches us to make teshuvah every night before we sleep. (This is one of the reasons behind saying the nighttime vidui as part of the bedtime shema: saying "I forgive anyone / who hurt or upset me or offended me..." allows us to let go of our angers and our hurts before we sleep, so that if we should die in the night, our souls are not encumbered by all of that baggage.) For me, one of the most important parts of making teshuvah is trying to let go: of the places where I've screwed up, of the places where other people have screwed up, of my unmet expectations. For those of us who aren't near death (as far as we know), that's an ongoing process. For those who may be aware that death is coming, I imagine that the urgency of that work might feel heightened.

I suspect that most of us feel the natural inclination to not want to think about death -- our own, or that of our loved ones. Our culture teaches us to focus on the positive, to anticipate happy outcomes, not to talk about the inevitable reality that life is finite and that all of us will someday die. But Jewish tradition offers us a lot of tools and technologies for navigating this transition -- both the transition of the person who is dying, from this life into whatever comes next, and the transition of the family and friends who will move from anticipation to mourning and grief.

Jewish tradition acknowledges that death is real, that it will happen to all of us, that it is natural and normal. (I'm thinking here of our funeral customs, including the gentle washing and dressing of the body performed by the chevra kadisha, and of the custom of burying our dead in simple linen garments and biodegradable pine boxes. No wreaths of cut flowers, no enbalming or cosmetics to allow us to pretend for the duration of the funeral that our loved one is merely "sleeping.) For those who walk the mourner's path we have the traditions of shiva and shloshim (the first week and month of mourning), the recitation of the mourner's kaddish, and other prayers and psalms to help ourselves heal and perhaps to help the soul of our loved one ascend along its path. For those who are caring for mourners we have a rich tradition of nichum avelim, comforting the bereaved.

But for those who are preparing to die, the vidui is one of our most powerful tools for cultivating acceptance and for letting go gracefully and at peace.

For more on this: Dr./RP Simcha Raphael works as a death awareness educator, and I can recommend his book Jewish Views of the Afterlife.

A short teaching from Reb Zalman on how prayer can change our minds

"There is a mantra in our heads which says to us that we are no good and we need to change."

"Like erasing a tape by using a high pitched sound, beyond audibility, which then allows the new stuff to be recorded, we need a newer, more positive mantra so that we can change how we think about ourselves."

"This is what davvenen / prayer is for."

-- Reb Zalman, in A Guide for Starting Your New Incarnation

(available as a pdf download from the ALEPH Canada store.)

"There is a mantra in our heads which says to us that we are no good." Who among us hasn't heard that voice? Sometimes I associate that voice with the voice our sages called the yetzer ha-ra, the "bad inclination."

In the traditional understanding, each of us has a good inclination and a bad inclination. For our sages the bad inclination and the good inclination are always inevitably bound up together. We need both of them. (There's a great midrash about how the rabbis once managed to imprison the yetzer ha-ra and for three days, until it was freed, no eggs were laid throughout the land. Without the tension between our impulses, between good and bad, there's no fruitfulness, no generativity.) But one of the ways I've experienced my own yetzer ha-ra is as the voice of excessive internal critique.

Sometimes that critique is productive and nudges me to do better, in which case I should listen to it. Other times it just makes me feel lousy, in which case I should ignore it. The challenge is discerning which times are which! I remember talking in rabbinic school with my friend (now Rabbi) Simcha Daniel Burstyn about how the yetzer ha-ra is the voice which whispers to us that we don't have time to daven properly, with full intention, so we might as well not even try. It makes the perfect into the enemy of the good. The way to triumph over it is to plough ahead and engage in our practice, even if we know we're not going to do it with perfect full heart and perfect focus and perfect everything. Even if we know we aren't going to be perfect.

We were talking about davenen, but it could as easily apply to other practices: meditation, yoga, exercise, volunteer work, spending time with one's family. It's so easy to slip into feeling as though, if we can't do something 100% the way we wish we could, then we might as well not try. I still work at noticing that pattern; recognizing it for what it is, without judgement; and then letting it go. Maybe this is why I gravitate toward Reb Zalman's idea that the tape of negativity can be erased (or at least mitigated) through the use of a new mantra which will overwrite the old one -- and that davenen, prayer, is our tradition's primary tool for doing that work.

Davenen is a Yiddish word. In Hebrew, we have two words which mean prayer. One of them is avodah, service. The priests of old performed the service of the sacrifices; in our day we engage in avodah she-ba-lev, the service of the heart, when we offer up our words. And the other word is tefilah, which comes from l'hitpallel, which means to discern or to judge. When we pray, we serve something greater than ourselves; we reaffirm for ourselves that we did not create everything around us, that we are not the center of the universe, that there are reasons to offer thanks and praise. And through our practice of prayer, we can discern things about ourselves. What speaks to you in a particular prayer today may not speak to you next week. There will be days when the prayers feel alive and sparkling, and days when they feel rote. The words don't change, but we do.

And our practices change as our lives do. (See This is spiritual life, 2011, and especially Prayer life changes, 2010.) For me it was becoming a parent which led to that realization. My prayer life couldn't be what it was before I had a child. I was too taken-up with the details of childcare, physically and emotionally. But I learned that my prayer life could be something different, something equally beautiful and meaningful, when I embraced the kinds of praying I was uniquely able to do at that moment in my life. For others, this realization might arise because of a job change -- a move to a new place -- an unexpected illness -- any of life's curveballs. One of the hidden upsides of trying to daven with a newborn was that I figured out pretty quickly which prayers were essential to me, which prayers I absolutely had to find a way to say.

One of the things I've learned over the years is that I am healthier and happier when I articulate gratitude every morning (via modah ani and other gratitude practices), and when I pause to forgive everyone who's hurt me that day as I approach sleep (via the bedtime shema and the forgiveness prayer I so love.) The corollary which I've also learned, to my chagrin, is that when I'm in a tough emotional or spiritual place, I have trouble doing those very things. Or, perhaps it works the other way -- that when I can't access gratitude and forgiveness, that's a signal to me that something is awry and requires tending and care. Being attuned to my prayer life, and its ebbs and flows, helps me stay attuned to my own internal landscape. This is how I understand the the definitions of the verb l'hitpallel, to pray/to discern/to judge -- when I make time for prayer, I'm able to discern what's happening in my interior life.

In that same section of this booklet, Reb Zalman writes:

Reb Nachman of Bratzlav has this wonderful teaching. He says that if I want to undertake to do something good, like I want to learn, then the best way to help myself get started is to spend some time imagining what it feels like to learn.

I love this little teaching, too. If I want to experience gratitude, I can spend some time imagining what it would feel like to get there. If I want to pray with my whole heart, I can spend some time imagining what it would feel like to do that. The imagining becomes a kind of mental road map. If I've "been there before," even only in imagination, that can help me get there again.

One of the great gifts for me of being a working rabbi is that one component of my job is leading davenen. When I lead services, I have an opportunity to recite (and hopefully to feel and to mean) some of the prayers I need to be saying. But on days when I'm not leading others in prayer, my own prayer life varies wildly. Although our son is now four, it's still rare for me to give myself the spaciousness to spend a long time in solo prayer (much less to daven in community) unless I'm on retreat. But there are a few prayers I try to say every day. And sometimes when I'm driving I'll quietly sing as much of the evening service as I know by heart, harmonizing weekday nusach with the tone created by the wheels of the car.

Here's something else that strikes me about this short teaching from Reb Zalman. He says prayer is the practice designed to help us overwrite the voice in our heads -- the one which says "we're no good," and the one which says "we have to change." I think that he means both clauses. Not only the "we're no good" part, but also the "we have to change" part. Maybe practicing prayer can help us not only to discern who we most deeply are, but also to recognize that in our deepest selves, we don't need to change -- we're wonderful already, imperfections and all, just the way we are.

Photo source: my flickr photostream.

December 5, 2013

This week's portion: when we reveal ourselves

This week we are reading parashat Vayigash.

When Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, they are stunned into silence.

He draws them close, and urges them not to be troubled or upset by having sold him into slavery. Not they, he says, but God is the One who truly sent him down into Egypt. God did this in order that he might be there to help interpret Pharaoh's dream of lean cows devouring the fat ones, in order to convince Pharaoh to stockpile grain against the coming years of famine, in order that when his family came begging for food he could not only feed them but bring them all down to herd their flocks on Egypt's fertile soil.

Then he falls weeping on his brother's neck, and Benjamin weeps with him; and he kisses all of his brothers and weeps with them. Only after this can his brothers respond to him.

When we reveal our true selves, removing the masks with which we disguse our deepest identity and our souls' own light, both we and those to whom we reveal ourselves may weep. Emotions may run high. Revealing who we really are, in all of our vulnerabilities and differences, requires great bravery. But it is only through that revelation, and through the healing tears which ensue, that we can begin to truly respond to one another -- to speak to, and from, the heart of who we really are.

December 4, 2013

Three tiny teachings on Chanukah's light

The Bnei Yissaschar (Rabbi Zvi Elimelech of Dinov) teaches: On Chanukah, we are given part of the or ha-ganuz, the primordial light which has been hidden-away since the moment of Creation and which is preserved for the righteous in the world to come. (This is the light of the first day of creation, before the sun and moon and stars were created; not literal light, but a kind of spiritual or metaphysical light, the light of expanded consciousness.) With this light, you could see from one end of the earth to the other. And with this light, we kindle other holy lights -- the souls within each of us.

The Bnei Yissaschar (Rabbi Zvi Elimelech of Dinov) teaches: On Chanukah, we are given part of the or ha-ganuz, the primordial light which has been hidden-away since the moment of Creation and which is preserved for the righteous in the world to come. (This is the light of the first day of creation, before the sun and moon and stars were created; not literal light, but a kind of spiritual or metaphysical light, the light of expanded consciousness.) With this light, you could see from one end of the earth to the other. And with this light, we kindle other holy lights -- the souls within each of us.

(From his teachings on the month of Kislev; the final insight comes from Michael Strassfeld's commentary in The Jewish Holidays.)

The Sfat Emet (Rabbi Yehuda Leib Alter of Ger) teaches: "The candle of God is the soul of man, searching all of one's deepest places." (Proverbs 20:27) In the spring we search our homes for leaven with a candle. (That's the ritual of bedikat chametz, hiding some leaven around the house and then "discovering" it with a candle, to ceremonially burn it before the holday begins.) At this season, we search our innermost selves for the spark of God which illuminates us (as the Chanukah candles illuminate what's around us.)

The mishkan, the dwelling-place-for-God (e.g. the holy Temple, the one whose rededication we celebrate at this season even though it's been destroyed now for almost two thousand years) -- that holy dwelling-place is within each of us, as we read in Torah, "they shall build for Me a sanctuary and I will dwell within them." (In other words: we built the sanctuary not so that God could live in it, but so that through the process of the building we might open our hearts for God to dwell in us.)

The Temple no longer exists; in our era the mishkan is hidden -- but we can still find it by searching for it, which we do with the (metaphorical) candles of the mitzvot. We search for God's presence by "lighting the candles" of doing mitzvot. Doing mitzvot with all of our hearts, our souls, our life-force, is a way of searching for God's presence in the world. Through doing mitzvot with intention and awareness, we are able to find the point within us which is the hidden mishkan, the dwelling place for God.

(Here's a longer exploration of this teaching: Sfat Emet on light and Chanukah, 2010.)

The Sfat Emet also teaches: The miracle of Chanukah was one of light. This light allows us to find the hidden illumination / enlightenment which is in darkness and in our alienation.

* * *

As we kindle the Chanukah lights tonight for the last time this year, may we experience their light as a glimpse of that primordial light from the first moment of creation; may we find our souls kindled through the act of doing this mitzvah, and may we recognize ourselves as dwelling-places for God's presence; and may our lights connect us with the hidden illumination which can be found in even our darkest emotional and spiritual places.

December 3, 2013

New poem at Satya Robin's site

My friend Satya Robyn of Writing Our Way Home did a really neat thing to celebrate the launch of her newest book, Afterwards: she invited a variety of writers and artists to create new works on the theme "afterwards," and created an online gallery of that new work, which premiered on the day that the book launched.

I was honored when Satya asked me to participate in her virtual launch party, and even more delighted when I saw the wonderful other works in the gallery, including artwork by Rosemary Starace and new poetry from Luisa Igloria.

My contribution is a poem called "After," which begins "After the wrong-footed morning / after the temper tantrum..." I suspect that the emotional arc of the poem will be familiar to parents of young children, though I hope the poem will speak also to those who are not parents.

Here's the virtual gallery -- go and enjoy, and consider picking up Satya's latest!

December 2, 2013

Chanukah and the obligation to sit still and notice

One of the customs of Chanukah is to sing a couple of hymns after we light Chanukah candles. One of them is Maoz Tzur, "Rock of Ages." (Here's an abbreviation of the traditional version. Here's Reb Zalman's version, which is singable to the same tune but celebrates the miracles of Chanukah in a different way.) And the other hymn is Hanerot Hallalu, "The lights which we light." Here's that second one:

"We light these lights for [commemoration of] the miracles and the wonders, for the redemption and the battles that you made for our ancestors, in those days at this season, through your holy priests. During all eight days of Chanukah these lights are sacred, and we are not permitted to make ordinary use of them except to look at them in order to express thanks and praise to Your great Name for Your miracles, Your wonders and Your salvations." (From Talmud, Sofrim 20:6)

This little song is often overlooked and is not well known. Which is a shame, because it's quite wonderful.

Hanerot Hallalu teaches us that we light the candles of the chanukiyyah in order to remember miracles and wonders, and that their light is holy -- so holy, in fact, that we're not supposed to use that light for ordinary things. Instead, our job is to just enjoy them. To look at them. To contemplate them, and their small beauty, and to cultivate an upwelling of thanks and praise. In this way, Chanukah invites us into contemplative practice.

The Shabbat candles which we kindle each week are also holy. But they don't come with this same obligation. It's perfectly permissible to eat one's Shabbat dinner by the light of the Shabbat candles. But the Chanukah candles aren't meant to be used in any mundane way. The shamash candle, the "helper" which lights the others, casts ordinary usable light. But the eight candles in the chanukiyyah proper are there not to give us light to do the dishes by -- they're there to give us a meditative focus, something to look at as we coax wonder and gratitude to arise within us.

At this hectic season -- Thanksgiving and "Black Friday" just past, Christmas and New Year's on the horizon, everywhere around us a tumult of coveting and shopping and spending, the academic semester racing to its finale -- the very idea of taking the duration of the Chanukah candles as a time for quiet and meditation seems like a miracle. May we all be blessed to find our moments of stillness and peace as the candles burn low.

Here's a choral setting of Hanerot Hallalu. And here's a solo setting of an unknown melody. If your tastes run more toward a cappella, here's Six13's version. And here's a simple sung version, accompanied beautifully on piano.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers