Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 175

October 21, 2013

On death and land: thoughts on Chayei Sarah

In the first line of this week's Torah portion (Chayei Sarah) the matriarch Sarah dies, and Avraham negotiates to buy a burial place for her: the cave of Machpelah in what is now Hebron. Our first record of ownership of any of the land of Canaan is thus the purchase of a cemetery plot. Land ownership, death, and permanence seem to be linked: while alive, Sarah wandered the land, but now that she is dead, she is fixed in place. When we die, our lives become fixed as though in amber. Whatever stories were told about us while we lived -- those stories calcify like the fossils in the seabed of our ancient seas.

In the first line of this week's Torah portion (Chayei Sarah) the matriarch Sarah dies, and Avraham negotiates to buy a burial place for her: the cave of Machpelah in what is now Hebron. Our first record of ownership of any of the land of Canaan is thus the purchase of a cemetery plot. Land ownership, death, and permanence seem to be linked: while alive, Sarah wandered the land, but now that she is dead, she is fixed in place. When we die, our lives become fixed as though in amber. Whatever stories were told about us while we lived -- those stories calcify like the fossils in the seabed of our ancient seas.

By the end of the portion, Avraham too dies, and his two sons -- Isaac born to Sarah, and Ishmael born to Hagar -- bury him in the same cave where he had buried Sarah. This parsha begins and ends with death. All roads in this portion lead to the cave, the tomb, the entrance into the earth. Maybe in their father's death the two half-brothers are able, however temporarily, to reconcile... or maybe Avraham's absence just heightens their alienation from each other, the ways in which they remember the same stories from childhood through different lenses, trauma in one brother's memory transmuted in the other brother's mind into rosy-hued comfort.

Reading this Torah portion now, I can't help thinking about the modern-day city of Hebron, which I visited several years ago and hope to visit again next year. I think about the continuing tensions between the spiritual descendents of Isaac and the spiritual descendants of Ishmael, and how those tensions have played out at the very site (more or less) which our two traditions hold to be Abraham's burial-place -- from the Cave of the Patriarchs Massacre to recent tensions in the South Hebron Hills. And then I think about initiatives like Project Hayei Sarah ("A group of rabbinical students, rabbis, Jewish educators &

lay-leaders who have spent time in Hebron and are grappling with the

difficult realities we encountered there") and this week's Christian Science Monitor story Why rabbis are helping Palestinians with olive harvests, and I wonder whether projects like those offer threads of hope to which we can cling.

The dead don't fight over who promised what to whom, but we, the living -- we contend bitterly over who has the right version of the truth. This is true on the microcosmic level of an individual family's narratives, and it's true on the macrocosmic level of the descendants of Abraham / Ibrahim -- the vast family narrative of which our traditions tell us we are a part. Every year as we return to parashat Chayei Sarah, I reread the story of my teacher Reb Zalman among the Sufis of Hebron, and I wish that more of us could meet others -- and Others, those whom our stories and our perspectives cast as being different from us -- the way that my teachers have taught me to try to do. What would it take to bring life to our relationships with our cousins from the line of Ishmael -- to say that our interactions don't have to be calcified like the ossified remains of our ancestors, but can instead be alive to growth and change, filled with connection and possibility?

Previous years' divrei Torah on this portion:

2005: Chayyei Sarah: the meaning of ownership

2008: In the same key [Torah poem]

2009: Departure [Torah poem]

2010: The years of my life

Photo source (Tomb of Abraham mosaic): my flickr stream.

Prayer/poem for autumn nightfall

Autumn Nightfall

You mix the watercolors of the evening

like my son, swishing his brush

until the waters are black with paint.

The sky is streaked and dimming.

The sun wheels over the horizon

like a glowing penny falling into its slot.

Day is spent, and in its place: the changing moon,

the spatterdash of stars across the sky's expanse.

Every evening we tell ourselves the old story:

You cover over our sins, forgiveness

like a fleece blanket tucked around our ears.

When we cry out, You will hear.

Soothe my fear of life without enough light.

Rock me to sleep in the deepening dark.

This coming Friday I'll be teaching the first of a series of monthly classes on the poetry of Jewish liturgical prayer at the coffee shop in my town. (The class is free and open to all.) We'll begin by looking at one of my favorite Hebrew prayers which is also a poem: the ma'ariv aravim blessing for God Who brings on (or "evens") the evenings. Once we've spent some time with the poetry of the prayer itself, we'll also look at some adaptations and some other poems on similar themes, ranging from Rabbi Rayzel Raphael's "Evening the Evenings" to Jane Kenyon's "Let Evening Come" to this new poem of my own.

The final lines are a reference to the prelude to evening prayer, v'hu rachum, a pair of lines from Psalm 78 and from psalm 20. As Elliott Dorff notes (in My People's Prayer Book Vol. 9: Welcoming the Night), "The evening liturgy begins by acknowledging human vulnerability occasioned by nighttime darkness. God, we are assured, will save us from potential dangers. God will protect us from what we fear." As the parent of a young child who is afraid of the dark, I find these lines particularly resonant now. And, of course, many adults who no longer fear the dark still fear the onset of winter's long darkness.

Photo source: my flickr stream.

October 18, 2013

Forgiving our ancestors: a practice for Vayera

In this week's parsha we encounter some of our tradition's most compelling -- and most complicated -- family stories. Here are the angelic beings announcing the upcoming conception of Isaac; Sarah's jealousy, and the casting-out of Hagar and Ishmael; Avraham arguing to try to save the people of Sodom; and the akedah, the Binding of Isaac.

In this week's parsha we encounter some of our tradition's most compelling -- and most complicated -- family stories. Here are the angelic beings announcing the upcoming conception of Isaac; Sarah's jealousy, and the casting-out of Hagar and Ishmael; Avraham arguing to try to save the people of Sodom; and the akedah, the Binding of Isaac.

This year as we return to this story I'm moved by the sense that this week's parsha offers us an opportunity to do the work of forgiveness.

What would it feel like to forgive Avraham for his role in our family story -- for his willingness to argue with God to save strangers but not to save his own sons; for his admirable hospitality to strangers matched with his willingness to allow Hagar and Ishmael to be cast into the desert? What would it feel like to forgive Sarah for her role in our family story -- for her desperation to have a child, for her jealousy of her handmaiden and of that handmaiden's son? What would it feel like to forgive Isaac for being, at least on the surface of the text, a silent victim who doesn't try to save himself?

Does it seem strange to imagine extending forgiveness to these ancient Biblical forebears? I believe that there are ways in which their choices -- the things they said, and the things they didn't say; their actions, and their inactions -- continue to reverberate in the family story we share.

Part of the reason why reading Genesis is so compelling is that its themes -- including spousal jealousy, sibling competition, and parental favoritism -- are still unfolding in our world. What would it feel like to forgive our more immediate ancestors (parents, grandparents, great-grandparents) for the places where they missed the mark? To recognize the dynamics of our own family systems and to meet those dynamics not with anger but with kindness and compassion?

Today's practice, for those who are so inclined, is a practice of forgiveness. Inhaling, we address our own hearts: Heart! And exhaling, we make a request: Forgive. Heart, forgive. Heart, forgive.

What arises in us as we try to cultivate forgiveness for the flawed people in our family story?

This post is a written adaptation of a practice I offered aloud at this morning's meditation minyan at my shul. The accompanying image is from here, artist unknown. For a more nuanced look at questions of forgiveness, try my post #BlogElul 13: Forgive.

Previous years' commentary on this week's Torah portion:

2006: Radical Hospitality (originally published at Radical Torah)

2008: Silence [Torah poem]

2009: Aftermath [Torah poem]

2010: The Akedah Cycle [ten linked Torah poems on the Binding of Isaac]

2010: The entrance to holiness

2012: Sodom and Gomorrah, Hurricane Sandy, and God

October 16, 2013

Firmanent / Tearing

"And God said, let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters,

and let it divide the waters from the waters." -- Genesis 1:6

Our sages teach: read not "firmanent"

but "rupture." Swap two sounds

in the original Hebrew

and the vastness of the sky's expanse

becomes the primal tearing

at creation's birth, God wounded.

Our stories teach: all the waters

wanted to be in the realms above

until God, angered, crooked His finger

and the fabric of the cosmos tore.

This dissent is why Torah doesn't say

God saw that it was good.

Only the second day of existence

and God wore that ripped scrap of gabardine

which speaks mourning: "as our lives

are torn, we perform this act of keria..."

God divided the waters of birth

from all our sea-salt tears to come.

Every birth is also a death: the end

of the life that used to be.

Every separation is also a rupture.

Read not "good" but "God:" God saw

that creation was constantly changing

just like its creator, dividing and torn.

This poem arises out of this week's material in Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel's Heavenly Torah. Heschel writes:

Regarding the waters: On the second day of creation, the Holy and Blessed One said: "let there be an expanse (raki'a) in the midst of the water, that it may separate water from water. God made the expanse and it separated the water that was below the expanse from the water which was above the expanse" (Genesis 1:6-7). "God said to the waters: divide yourselves into two halves; one haf shall go up, and the other half shall go down; but the waters presumptuously all went upward. Said to them the Holy and Blessed One: I told you that only half should go upward, and all of you went upward?! Said the waters: We shall not descend! Thus did they brazenly confront their Creator... What did the Holy and Blessed One do? God extended His little finger, and they tore into two parts, and God took half of them down against their will. Thus it is written, 'God said, let there be an expanse (raki'a) -- do not read 'expanse, but 'tear' (keri'a)." (Midrash Konen, Otzar Midrashim, p. 254)

In a footnote, translator and editor Rabbi Gordon Tucker adds:

The Hebrew keri'a is an anagram of raki'a. This is quite an impressive midrash, coming from the early medieval collection known as Midrash Konen. This passage makes obvous analogies between God's creation and human birth. Both involve waters breaking, both involve pain and a tear. The tear in the waters was necessary to create space in which life could develop, and the tear of birth is necesary for the baby to begin an independent life. Keri'a is the rite for the dead, when Jewish law requires the tearing of clothing. The message then is twofold: the tear of death is just the continuation of the tear of birth. Both are necessary for life to continue, and we are powerless to change that. The other message is that God is as much bound by these truths as we are. God also could not create without a day of division and tearing, and thus we and God are both in need of comfort and strength in the wake of the cruelties of nature.

It's a tremendous chapter. My poem is offered in humble homage.

Photo taken at South Padre Island.

October 15, 2013

Dip into the Storehouse; let your creativity run free!

Earlier this month I put up a post at the Best American Poetry blog called Collaboration and remix, in which I aimed to explore some of the new and exciting things happening online where poetry is concerned: creative collaborations, the flowering of remix culture (in which one artist might respond to or riff off of another artist's work, perhaps in the same artistic genre and perhaps in a different one), videopoetry and so on. Behind the scenes, some conversations bubbled up. And today -- thanks to Nic Sebastian and other collaborators -- the Poetry Storehouse is launched -- a new edited / moderated archive of poems available (under an attribution / noncommercial Creative Commons license) for creative use, re-use, remix, transformation, etc.

Here's a glimpse of what it says on the "About" page:

The Poetry Storehouse is an effort to promote new forms and

delivery methods for page-poetry by creating a repository of

freely-available high-quality contemporary poetry for those multimedia

collaborative artists who may sometimes be stymied in their work by

copyright and other restrictions.

Technology has not just connected people and poetry and poets and

artists who weren’t connected to each other before, it has also changed

both the face and the delivery of poetry itself. Poems locked up in

hard-copy print editions only available for sale are struggling in new

and serious ways, while poems delivered in multiple creative ways online

have new leases on life and are reaching an ever-widening audience.

We believe that creative energy, like physical energy, is never

created from scratch, nor does it ever die, but continually morphs from

form to form as each of us is inspired by what has gone before us and in

turn inspire what comes after us.

A handful of poets (me included) have submitted our work to seed the new archive. (Here are my submitted poems -- and I'm chuffed to be able to announce that Nic Sebastian has already created a transformative work; she's recorded one of my poems, "Lunaria Annua," and it's delightful to hear it given life in someone else's voice and intonations!) If you're an artist looking for poetry to play with, the storehouse contains poems ready for use in visual art or music or video or whatever your genre may be -- and if you're a poet interested in being part of this great collaboration, you can submit your work for consideration by the Poetry Storehouse editorial team.

Also don't miss the Sample Remixes section of the site, which features links to some incredibly cool work already.

October 14, 2013

Some of Montreal's small pleasures

A latte the size of my head (okay, not really, but it comes in a bowl, which I can't help but admire):

Interesting graffiti (a form of art which I've photographed in this city before, though not this specific piece of it):

Windows filled with fascinating treasure:

An old car with beautiful wheels (look at the wooden spokes!)

An impromptu picnic in the park with dear friends:

I'm grateful to have had the chance to spend a couple of days in this city -- and to share poems from Waiting to Unfold alongside stories of parenthood and spirituality, poems from 70 faces alongside a sermon.

(I'm home now. Thanks, Montreal, for a lovely time!)

October 13, 2013

On gratitude and thanks: a sermon for the UU community of Montreal

This is the sermon I offered this morning at the Unitarian Church of Montreal. Thanks so much for welcoming me, UU community of Montreal!

מֹודה אֲנִי לְפָנֶיָך, מֶלְֶך חַי וְַקּיָם, ׁשֶהֶחֱזְַרּתָ ּבִי נִׁשְמָתִי ּבְחֶמְלָה. ַרּבָה אֱמּונָתֶָך!

"I give thanks before You, living and enduring God.

You have restored my soul to me.

Great is Your faithfulness!"

This prayer is part of Jewish morning liturgy. It's in our prayerbook, and is often recited at the beginning of communal morning worship -- though in its most original context, it's meant to be recited before we even make it to synagogue in the morning. Modah ani is something we're meant to say upon waking up, first thing.

Some of you may have grown up reciting the 18th-century classic "Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep" before bed. That prayer has its roots in the Jewish custom of the bedtime Shema. Before bed, we say a prayer reminding ourselves that we place our souls in God's keeping while we are asleep. And when we wake again in the morning -- and, mirabile dictu, we're alive again! -- we offer this prayer of gratitude. Thank You, God, for giving my soul back to me! Great is Your faithfulness!

I'm often struck by that line. "Great is Your faithfulness." Often we think of faith -- in Hebrew, אמונה –– as something we're meant to have. We have faith in God. But in this prayer, it's the other way around. God is the one with emunah. God has faith in us.

There's something very powerful for me about asserting that, first thing in the morning. Today is a new day, rich with possibility. I am awaken and alive; I am a soul, embodied. And, my tradition teaches, God has faith in me and in what my day might contain.

In the traditional Jewish morning liturgy, shortly after Modah Ani there's a series of one-liners, called in some prayerbooks the "Blessings for the Miracles of Each Day." We bless God, the Source of All, for giving the bird of dawn the discernment to tell day from night. (In other words, it's a blessing of gratitude for the rooster, or whateverwakes us from sleep.) We bless God, Source of All, Who gives sight to the blind; Who clothes the naked; Who wipes sleep from the eyes and slumber from the eyelids.

These blessings too have migrated into our prayerbook, though I like to remind my community that they were originally intended to be prayed organically. But on the off-chance that perhaps we didn't thank God for the alarm clock this morning, or for straightening our spines as we got out of bed, or for giving strength to the weary, we do so together as part of our daily liturgy. These blessings, and the Modah Ani which comes before them, are part of a daily gratitude practice. And I believe that whether or not one "believes" in "God," that daily gratitude practice has value.

A poem from my forthcoming collection Open My Lips (due from Ben Yehuda Press next year):

Daily Miracles

You bring my son's footfalls to my door

and shock me awake with his cold heels against my ribs.

You teach me to distinguish waking life from dreaming.

You press the wooden floor against the soles of my feet.

You slip my eyeglasses into my questing hand

and the world comes into focus again.

In the time before time You collected hydrogen and oxygen

into molecules which stream now from my showerhead.

You enfold me in this bathtowel.

You enliven me with coffee.

Every morning you remake me in your image

and free me to push back against my fears.

You are the balance that holds up my spine,

the light in my gritty, grateful eyes.

I wrote this poem as a kind of contemporary, and very personal, adaptation of that series of traditional morning blessings. I don't get woken up by a rooster, nor even a clock-radio: I get woken every day by my son, who is almost four. I do experience the restoration of sight to my nearly-blind eyes -- through the medium of these lenses, ground by professionals with precision and care. And so on.

There's a blessing in Jewish liturgy which praises God Who enlivens the dead. In its original context, it referred to resurrection, in which my ancient ancestors believed. I've chosen to read it differently, and I frequently recite it when I step into the shower in the morning and am awakened by its blissful heat -- or when I tip back the day's first swallow of coffee. These are some of the ways in which I experience God's presence in my day, every day, and when I stop to say thank you, I notice God more.

My teacher Reb Zalman -- Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi -- is reported to have had a conversation with someone once in which the questioner began by asserting that he didn't believe in God. Without missing a beat (at least as I've heard the story told), Reb Zalman mildly agreed, "The God you don't believe in? I don't believe in either." The word "God" can mean an awful lot of things -- even just in Jewish tradition! For me, more important than the meaning of that word is the sense of relationship which it represents. God is the One With Whom I am always in relationship.

Here's another from Open My Lips:

Morning Prayer

Some days I say good morning

while the hose splashes into the kiddie pool

and the cat sniffs curiously at its curls

my lightest tallit

a sweep of blue silk

across bare shoulders

Blessed are You

Who straightens the bent, I sing

as I reach for the heavens

and blessed is the One

Who speaks creation into being,

walking across a patch of wild thyme

the mosquitoes want to rejoice in me

so I swish my tzitzit

inscribing letters on the air

then swirl my tallit off

like a bullfighter's cloak

blue rippling around my fingers

it's time to go inside

I turn off the faucet

but Your abundance keeps flowing

The metaphor which depicts God as the cosmic source of blessing, and our prayers as the act of turning on the spigot so blessing can flow, comes from the sages of my tradition. My teacher Rabbi Marcia Prayer teaches, in her tremendous book The Path of Blessing, that this is one way of understanding the traditional "blessing formula," the formulaic way in which most Jewish blessings and prayers begin.

בָרּוְך אַּתָה יי אֱֹלהֵינּו מֶלְֶך הָעֹולָם -- these words are usually rendered something like "Blessed are You, O Lord our God, sovereign of all creation." But Rabbi Prager notes that the word baruch, "blessed," is related to breikha, "fountain", and berekh, "knee:" what might that tell us about the act of blessing, the flow inherent in the practice, or the emotional/spiritual stance it might require?

She writes: "Jewish tradition teaches that the simple action of a brakha has a cosmic effect, for a brakha causes shefa, the 'abundant flow' of God's love and goodness, to pour into the world. Like a hand on the faucet, each brakha turns on the tap."

Jewish tradition holds that we should make 100 blessings each day. Imagine that: in every day, one hundred opportunities for mindfulness and gratitude!

A poem of gratitude from Waiting to Unfold:

ONE YEAR (MOTHER PSALM 9)

A psalm of ascent

When the doctor brought you

through my narrow places

I was as in a dream: tucked behind

my closed eyes, chanting silently

we are opening up in sweet surrender.

The night before we left the hospital

I wept: didn’t they know

I had no idea what to do with you?

Even newborn-sized clothes

loomed around you, vast and ill-fitting.

I couldn’t convince you to latch

without a nurse there to reposition.

But we got into the car, the old world

made terrifying and new, and

in time I learned your language.

I had my own narrow places ahead,

the valley of the postpartum shadow.

Nights when I would hand you over,

mutely grateful to anyone willing

to rock you down, to suffer your cries...

But those who sow in tears

will reap in joy, and you

are the joy I never knew I didn’t have.

I have paced these long hours

bearing a baby on my shoulder

and now I am home in rejoicing,

bearing you, my own harvest.

Sometimes we offer words of gratitude because we are already feeling grateful. And sometimes we come to feel grateful because we are offering words of gratitude. This is something I learned from my teacher Rabbi Jeff Roth many years ago: that when I'm not able to access the gratitude with which I want to invest my Modah Ani prayer, I can instead pray the traditional words in the hope that someday I might be able to feel gratitude again.

This morning we've entered together into a service of thanksgiving. One might ask: what is the relationship between thanksgiving and gratitude? It seems to me that gratitude is an attitude which may be a precursor to giving thanks... and sometimes giving thanks is a way of cultivating gratitude.

When we give thanks, we place ourselves in relationship to something greater than ourselves. Our prayers of thanksgiving and mindfulness carve channels of gratitude on our hearts, and the more frequently we carve those channels, the more easily our spirits flow in those directions.

A blessing for all of us who are here today: that in our prayer and fellowship this morning we might truly connect with gratitude and thanks -- and that as we offer thanks and praise, we may find ourselves changed by that practice; more open to recognizing daily miracles; more able to inhabit the gratitude with which we seek to imbue our days.

I spoke earlier about אמונה, the Hebrew word which means faith or faithfulness. The root of that word, א/ מ / נ, spells out a word with which some of you may be familiar; a word with which many of us have learned to seal our prayers. That word is Amen.

In Hebrew, Amen means something like: right on! I affirm that! So be it! It could mean: I believe that. Or perhaps, as Fox Mulder used to say, "I want to believe." If you'd like to affirm something you've heard this morning, or to offer a wish that you could feel some of what I've been describing, please join me in this practice from my tradition:

And let us say: Amen.

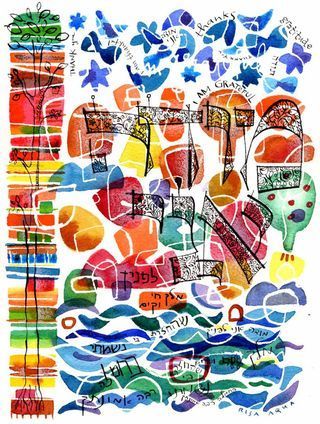

The image which illustrates this post is a print of the Modah Ani blessing, available on etsy, which hangs in my rabbinic office.

October 12, 2013

Illustrated travelogue

When I left home it was a beautiful afternoon:

I decided to take route 43 all the way to the Northway, and it was stunning:

I caught sight of Albany from a distance as I drove by:

The Adirondacks were pretty glorious, too:

But then the hills went away, and as soon as I crossed the border the fields were sere and flat:

And by the end of the day I was safely ensconced with friends, making Shabbat creatively with a tealight and a Montreal bagel!

October 11, 2013

Unify our hearts

וְיַחֵד לְבָבֵנוּ לְאַהֲבָה וּלְיִרְאָה אֶת שְׁמֶךָ.

וְיַחֵד לְבָבֵנוּ לְאַהֲבָה וּלְיִרְאָה אֶת שְׁמֶךָ.

V’yached l’vavenu, l’ahavah u-l’yirah et sh’mecha.

Unify our hearts in love and awe of Your name!

Unify our hearts. Perhaps that means the hearts of each of us in this room. Or the hearts of each of us in our community around the world. Unify our hearts, make our hearts beat as one.

In love and awe. Or, some would translate, love and fear. These are the two paths, the two doorways into serving God. Ahavah, love, is sometimes connected with chesed, lovingkindness which overflows. Yir'ah, awe, is sometimes connected with gevurah, boundaries which restrain.

There's a Hasidic teaching which says that awe and love are two wings, and that when they beat together, that's what lifts our prayers up to God. Another Hasidic teaching holds that most people come to serving God through the path of fear and awe, fear of judgement and of falling-short,

but that the path of love is the higher one.

Another way to understand this verse is: unify the disparate parts of each human heart. Unify the love in our hearts and the awe in our hearts. Help us to bring together our awe -- our radical amazement, our awareness of our own insignificance in the vast span of the cosmos! -- with our love.

A practice. Breathing in, we inhale awe. We inhale amazement. We inhale that sense that compared with God, compared with the universe, compared with the vast sweep of human history we are but specks of dust. And breathing out, we exhale love. We exhale compassion. We cultivate love for those around us, for those we meet, for those whom we know and those whom we don't know. Breathing in: awe. Breathing out: love.

Unify our hearts in the love and awe of Your Name.

This is a written (slightly expanded) version of a teaching I shared during my shul's meditation minyan this morning. See also Rabbi Shefa Gold's teaching and chant Unifying the heart.

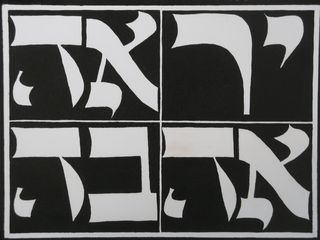

The image illustrating this post is calligraphy by soferet Julie Seltzer and features the words for love and awe, which, she notes, are intertwined and can be read either horizontally or vertically.

Book events across the border!

This morning, after I lead meditation at my synagogue, I'll pack my things and get ready to head up the Northway and across the border.

This morning, after I lead meditation at my synagogue, I'll pack my things and get ready to head up the Northway and across the border.

If you are in or near Montreal, I hope you'll join me for one or the other (or both!) of these two author events -- first a conversation (leavened with poetry) about parenthood and spiritual life at the Anglican Cathedral on Saturday afternoon at 1pm, and then a service at the Unitarian Church of Montreal on Sunday morning where I'll be sharing some poems and also the morning's sermon.

My wonderful publisher, Phoenicia, is based in Montreal -- hence the decision to head up there.  This was initially conceived as more of a book launch weekend last spring, but timing and scheduling and parenthood and logistics were difficult to resolve... so we postponed until autumn, after the Days of Awe were complete. Which is now!

This was initially conceived as more of a book launch weekend last spring, but timing and scheduling and parenthood and logistics were difficult to resolve... so we postponed until autumn, after the Days of Awe were complete. Which is now!

I'm looking really forward to the trip. I've been to Montreal several times before -- as a high school student on a French class trip (a big deal, coming all the way from south Texas!), for a mini-honeymoon right after our wedding, for a gathering with far-flung blogger friends, for a poetry reading and panel discussion when 70 faces first came out.

Every time I'm fortunate enough to visit, I experience a slightly different facet of the city -- which I was initially going to call beautiful and unique, though it occurs to me that those words are so banal as to be almost meaningless; surely every city is beautiful and unique, seen through the right eyes. But Montreal really is both of those things, and I'm looking forward to dipping into it again.

See y'all on the other side!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers