Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 174

November 3, 2013

Why am I, and how can I integrate? - questions from Toldot

Here's the short d'var Torah I offered yesterday morning during the contemplative Shabbat service at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

וַיִּתְרֹצֲצוּ הַבָּנִים בְּקִרְבָּהּ וַתֹּאמֶר אִם־כֵּן לָמָּה זֶּה אָנֹכִי וַתֵּלֶךְ לִדְרשׁ אֶת־יְי:

The children grappled with each other inside her, and she thought to herself: if this is so, why do I exist? So she went to ask that of Adonai.

וַיֹּאמֶר יְי לָהּ

שְׁנֵי גֹייִם בְּבִטְנֵךְ

וּשְׁנֵי לְאֻמִּים מִמֵּעַיִךְ

יִפָּרֵדוּ וּלְאֹם מִלְאֹם יֶאֱמָץ

וְרַב יַעֲבֹד צָעִיר:

And God said to her:

two nations are inside you;

two will branch off from each other, as they emerge from your womb.

One shall prevail over the other;

elder, serve younger.

If this is so, why do I exist? Or: If this is what's happening, why am I?

This is a fundamental question, and perhaps one which those with a contemplative bent know well. Why am I? Why am I me, and not someone else? Why is this life mine?

The word Rivka uses for "I" is anochi. Usually in Hebrew one uses the simple ani, I. But Rivka uses a kind of royal I, the same word used by God.

Rivka takes this question directly to that Anochi, to God, to Yud-Heh-Vav-Heh. That four-letter name can be understood as a form of the verb "to be" in all tenses at once: Was-Is-WillBe. Rivka takes her existential question to the Mystery at the heart of all things.

And that Mystery replies: there is a duality inside you. A pulling this way, and a pulling that way.

We all experience duality. Body and soul. I and thou. Insider and outsider. The wrestle of the twins in Rivka's womb can be a metaphor for the life each of us experiences.

The story of this parsha is a story of one twin overcoming the other. The younger brother, the trickster, the mama's boy, the underdog, winning out over the older brother, the hunter, daddy's favorite, the one who was supposed to inherit.

All over Genesis we find these inversions. Maybe this is a sign that we have always seen ourselves as an "underdog" people. But I always wonder what would have happened if the twins could have avoided their enmity.

And when I see Jacob and Esau as components of every human soul,I wonder what integration of those two sides might look like.

Jacob grabs his brother's heel in utero, and is therefore named Yakov, which relates to ekev, heel. Perhaps Jacob represents attachment. Holding-on. Clinging tightly.

Esau will become so hungry that he trades his birthright for a bowl of red lentils. Perhaps Esau represent desire. Craving. An existential emptiness which can't be filled.

Rivka's anochi is a kind of royal "I." It could also be understood as an integrated "I." When I can wholly integrate my inner Esau and my inner Jacob -- my body and my mind; my impulses and my forethought -- then, like Rivka, I can be an anochi.

What are the opposites which you struggle to integrate and reconcile?

What would it feel like to bring those opposites directly to God?

Who would you be if you could integrate them into one whole?

November 1, 2013

Excavating the Herodian oil lamps

Slit the packing tape. Lift the inner box.

Slit the packing tape. Lift the inner box.

Slide a knife again and listen to muted rainfall:

styrofoam pebbles pouring down.

The stand emerges first, round and heavy.

Then nine swaddled packages, light

as birds' bones, sized to fit in a palm.

Scissor gently through the bubble wrap,

unfold the layers to reveal ancient clay.

What foot pedaled the wheel, what fingers

wet with slip attached each graceful spout

and smoothed it with the flat of a knife

when Herod ruled in Jerusalem?

Two thousand years ago these held light

in the gloomy season on the cusp of Kislev.

Even now, in a world of compact fluorescents

and taillights glowing in the rain like rubies

we guard our wisps of flame, whatever lets us

hope even as the days grow dark.

My parents bought these lamps decades ago, while visiting my middle brother who was at the time working on a kibbutz. They date back to the early years of the Common Era. The person who sold them said, "they were found all together in a house; they must have been a menorah!" I suppose it's possible; the Chanukah story comes from the second century B.C.E., so it does predate these. In any case, the simple fact that they were made that long ago takes my breath away.

These used to be in my parents' bedroom, in the house I grew up in. I remember seeing them there countless times when I was a kid, and learning what they were, and how old, and where they had come from. In unboxing it now, there's a way in which I feel as though I'm excavating not only these artifacts from their storage, but also my own childhood. They grace my synagogue office now, a reminder of our deep-seated need (on both literal and metaphorical levels) to kindle light against the darkness.

For more on the lamps in question: Ancient Pottery Database: Herodian oil lamps; Fowler Bible Collection: Herodian Oil Lamp.

October 31, 2013

Duality within: on Toldot

The children grappled with each other inside her, and she thought to herself, if this is so, why do I exist? So she went to ask that of Adonai.

And God said to her: two nations are inside you; / two will branch off from each other, as they emerge from your womb. / One shall prevail over the other; the elder, serve the younger." (Genesis 25:22-24)

On the surface this appears to be a text about Rebecca and the twins battling in her womb. But the Torah is also a map for our own spiritual development, which means that this is also a text about each of us.

On the surface this appears to be a text about Rebecca and the twins battling in her womb. But the Torah is also a map for our own spiritual development, which means that this is also a text about each of us.

Our sages teach that each person has two inclinations or urges: the yetzer hatov (good inclination) and the yetzer hara (evil inclination.) This is inherent in our nature as human beings.

[Remember that, for our sages, the yetzer hara is an integral part of creation. In midrash we read that when the sages imprisoned the yetzer hara in a cage for three days, no eggs were laid throughout the land. Which is to say: without the yetzer hara, there's no generative impulse.]

But the yetzer hara can also lead us in bad directions. Sometimes when we pause to do the work of discernment, we discover that we're not acting out of a place that's elevated or useful; instead we're acting out of selfishness or fear or anger. One who makes such a discovery about themselves might offer the same existential cry that Rebecca did: "if this is so, then why am I here?" Why am I even alive in this world, if I'm not living out the best self I can be? What's the point?

But we can engage in practices which strengthen our yetzer hatov, our good inclination. We can be mindful and attentive to that within us which is driven by our bad impulse, and with our attention and energy can transform the bad into good. As it says in Psalms, "Turn bad into good." Increase your ability to take the yetzer hara which is within you, and invert or transform it into yetzer hatov.

When you do this, your yetzer hara will surrender and your yetzer hatov will emerge triumphant. And then it will be possible for you to really serve the Holy Blessed One, even with those aspects of yourself which feel linked to your yetzer hara.

(Gently adapted from the Degel Machaneh Efraim, the grandson of the Baal Shem Tov.)

This will be the Torah study text at my shul this Shabbat after our contemplative service, and I'll bring along some questions to hopefully spark our conversation. But I think this is one which merits thinking about for more than just one morning, so I'm sharing it here too. I welcome any responses y'all have to offer.

October 30, 2013

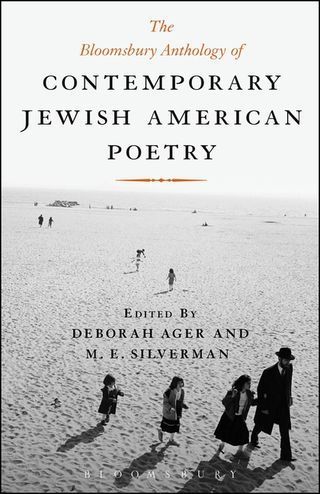

The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary American Jewish Poetry (including mine!)

I could not be more delighted to be able to share the news that I have two poems in The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry, edited by Deborah Ager and M.E. Silverman. Here's a glimpse of how the book describes itself: "With works by over 100 poets, The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry celebrates contemporary writers, born after World War II, who write about Jewish themes. // This anthology brings together poets whose writings offer fascinating insight into Jewish cultural and religious identity[.]" I am tremendously honored to be one of them!

I could not be more delighted to be able to share the news that I have two poems in The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry, edited by Deborah Ager and M.E. Silverman. Here's a glimpse of how the book describes itself: "With works by over 100 poets, The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry celebrates contemporary writers, born after World War II, who write about Jewish themes. // This anthology brings together poets whose writings offer fascinating insight into Jewish cultural and religious identity[.]" I am tremendously honored to be one of them!

Within these pages, we invite you to consider, explore, and reflect upon what shapes the heart of Jewish American poems that both celebrate Jewish traditions and honor the human spirit. In this book, we wanted to share distinctly Jewish American voices, which include second-generation Jews, converts, those on the path to conversion, secular Jews, a rabbi, those who've made Aliyah, and others. We included poems that both do and do not focus on Jewish themes, and we did that to convey the breadth and depth of Jewish personhood. With this book, we do not attempt to answer what it means to be Jewish in a time when so many follow a secular life. We seek to answer how the long history of Judaism expresses itself in the daily lives of the artists represented within these pages, and the poems do that on their own.

So write the editors in their "Invitation to the reader."

My work is included in these pages alongside work by many writers whom I have long admired -- Ellen Bass; Richard Chess, the former poetry editor at Zeek magazine; Lucille Lang Day; Julie R. Enszer; Amy Gerstler; Jane Hirschfield; Joy Ladin, whose (prose) work I've reviewed here before; my friend and teacher David Lehman (under whose tutelage I spent that grad school semester studying Jewish American literature of a variety of stripes, culminating in an attempt to define for myself what makes Jewish literature Jewish); Yehoshua November, whose work I've reviewed for Zeek; my teacher Jason Shinder, may his memory be a blessing; Matthew Zapruder; Rachel Zucker; and many more.

It's a gorgeous, broad, deep collection and I'm really happy that two of my poems -- "Eating the Apple" (which appears in Waiting to Unfold, Phoenicia 2013) and "Command (Tzav)" (which appears in 70 faces: Torah poems, Phoenicia 2011) -- are included. I'm further honored to be one of the voices in the "Further Reflections: Commentary on Jewish American Poetry" section at the end of the volume.

Deep thanks to the editors for including me and to the press for putting out such a beautiful volume. I know I'll be reading and rereading it for a long time to come.

Buy the anthology from the press ($29.95) | or from Amazon ($28.45) | or from Powell's ($36.75)

October 29, 2013

Judith Sarah Schmidt's deep Torah poetry for this week's portion, Toldot

In 2003, as I approached my seventieth birthday, I decided to be bat torah. The Torah portion I received to live with for that year was Toldot: Generations. I spent the year deep in study, reading many sources that informed me and inspired me. This study was absorbed into my midrashic meditations on the portion...

The "voices" of Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob, and Esau contained in these pages are the voices I have heard as I lived, this past year, with the Torah portion of Toldot. I have not only turned it and turned it; more often than not, it has turned and turned me. Our Torah opens ancestral doors through which I find them and also find myself in them and through them.

That's Judith Sarah Schmidt in the introduction to her book Longing for the Blessing: Midrashic Voices from Toldot, published by Time Being Books.

I spent a few years writing weekly Torah poems (the best of which -- and a full cycle of which -- are collected in my book 70 faces: Torah poems, Phoenicia 2011.) But my practice involved writing one poem each week during that week's parsha. I would live with the parsha and its commentaries and my responses to both for one week, and then I would move on, as our Torah reading cycle moves on. I am moved (and more than a little bit awed) by Schmidt's deep year-long journey into this one Torah portion.

The book is divided into sections: "Toldot, My Generations: Canaan," "Hearing the Voice of Jacob / Yaakov," " Hearing the Voice of Esau," "Hearing the Voice of Rebecca / Rifka," "My Generations: Boibrke, Poland," and "Midrashic Musings on Angels and Blessings." The Poland section features her midrashic explorations of her own toldot, generations; the final section is a long d'var Torah offered on her 70th birthday, in which she describes her journey and then shares perspectives on each of these Biblical characters and how she has come to find herself in them and to find them in herself.

Schmidt alternates between poetry and prose, and I frequently love the way she gives voice to these characters. For instance:

Esau's Sacrifice

My mother made a sacrifice of me.

Even before I was born,

I was the one she chose.

She had her reasons.

As she came to know

my lusty kick

against the walls of her womb,

she knew what my life could serve...

When my mother saw me,

she looked upon me

with her knowing smile.

I was the hairy twin,

the one to be put to good use,

to play the role

in the daily drama

of father's redemption.

That poem ends with Esau's poignant sorrow: "I only minded that...she never found me / behind my lonely eyes." The prose reflection which follows it depicts Esau's journey into the desert, and his meeting-up with his uncle Ishmael and his mother Hagar: "They told me that the healing of my starvation would come from drinking in the love of their tender and serious smiles." This is a kind of midrash which hasn't been told before.

Or this one:

Rebecca's Dream

I am in a green land.

The scent of myrtle trees

and the sounds of the turtle doves

fill the air.

I am with my husband, Yitzhak.

We are wrapped

in shimmering waters

under a silken sky.

He is holding me close

the way he used to.

We are moving together

like luminous slippery fish.

He is sliding the stars

into my dry heart.

My mouth is opening

I am crying out:

"Lord, fill my womb.

Make me mother,

Lord, make me mother."

I am swelling, I am swelling.

I am becoming river.

He is still holding me.

I love the way that Schmidt approaches the classical Biblical subject of fertility and yearning, and the sensuality of this poem is incredibly powerful, giving me a different sense of who Rebecca and Isaac might have been. These are just a glimpse; to get the full immersion experience of Schmidt's deep dive into this week's Torah portion, you'll need to pick up the whole collection! All in all, this is a wonderful collection to be reading this week as we navigate this parsha ourselves, and I can only admire Schmidt's dedication to this parsha and to bringing Torah to life in new and renewed ways.

If Torah poetry is your cup of tea, you might enjoy The Blessing, a Torah poem I wrote for this portion in 2012; or Birthings, the Torah poem I wrote for this portion in 2009; or Pulling the strings, which appears (lightly revised) in 70 faces: Torah poems.

October 27, 2013

Looking at the prayer for evening in a new light

I still remember the moment when I opened up my pocket Koren siddur (prayerbook) for the first time. It had been assigned to us by Rabbi Sami Barth, who was teaching my ALEPH rabbinic program class on the liturgy of weekday and Shabbat. He wanted all of us to own that siddur, it turned out, both because it's a good solid standard one to own and daven with -- and also because in that siddur, many of the prayers which are actually poetry are laid out on the page as poetry. Given that my background (before I came to the rabbinate) is in poetry, that was exactly the right thing to say to me to get me (even more) excited about studying liturgy!

I still remember the moment when I opened up my pocket Koren siddur (prayerbook) for the first time. It had been assigned to us by Rabbi Sami Barth, who was teaching my ALEPH rabbinic program class on the liturgy of weekday and Shabbat. He wanted all of us to own that siddur, it turned out, both because it's a good solid standard one to own and daven with -- and also because in that siddur, many of the prayers which are actually poetry are laid out on the page as poetry. Given that my background (before I came to the rabbinate) is in poetry, that was exactly the right thing to say to me to get me (even more) excited about studying liturgy!

That conversation was on my mind when I planned the monthly class I'm teaching in my community this fall and winter: a class on the poetry of Jewish liturgical prayer. Prayer as poetry; prayers as poetry; the poetry of our standard prayers as they've come down to us, both in Hebrew and in various English renderings and translations; and also poetry which doubles as prayer, especially if and when it works with the same ideas and themes as the classical material. It is probably no secret to anyone in my community that I floated this idea for a class because this is totally my idea of a good time. Last Friday that ad hoc group met for the first time, and it was such a joy for me, I can't even tell you.

The prayer I'd chosen for our focus was the ma'ariv aravim prayer, the prayer which speaks to / about God Who brings on (or, one might say, evens out) the evenings. I'd brought a handful of texts with me: the traditional prayer in Hebrew (along with translation and transliteration), an excerpt from an article about the ways in which this prayer works with language, a contemporary singable variation on the prayer by Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael, a prose reinterpretation of the prayer from a Reconstructionist prayerbook, and then two poems: one by Jane Kenyon (not explicitly liturgical) and a recent one by me (intended as a variation on this prayer's language and themes.) I'll share those same materials, along with a few observations, below.

Here's the classical prayer:

Ma'ariv Aravim: God of Day and Night

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ , אֶלֹהֵֽינוּ מֶֽלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם,

אֲשֶׁר בִּדְבָרוֹ מַעֲרִיב עֲרָבִים,

בְּחָכְמָה פּוֹתֵֽחַ שְׁעָרִים,

וּבִתְבוּנָה מְשַׁנֶּה עִתִּים,

וּמַחֲלִיף אֶת הַזְּמַנִּים,

וּמְסַדֵּר אֶת הַכּוֹכָבִים,

בְּמִשְׁמְרוֹתֵיהֶם בָּרָקִֽיעַ כְּרְצוֹנוֹ.

בּוֹרֵא יוֹם וָלָֽיְלָה,

גוֹלֵל אוֹר מִפְּנֵי חֽשֶׁךְ,

וחֽשֶׁךְ מִפְּנֵי אוֹר.

וּמַעֲבִיר יוֹם וּמֵֽבִיא לָֽיְלָה,

וּמַבְדִּיל בֵּין יוֹם וּבֵין לָֽיְלָה,

יְיָ צְבָאוֹת שְׁמוֹ.

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Source of all being,

by Whose word the evening falls.

In wisdom You open heaven’s gates.

With understanding You make seasons change,

causing the times to come and go,

and ordering the stars on their appointed paths

through heaven’s dome, all according to Your will.

Creator of day and night, who rolls back light before dark,

and dark before light, who makes day pass away

and brings on the night, dividing between day and night;

the Leader of Heaven's Multitudes is Your name!

אֵל חַי וְקַיָּם, תָּמִיד יִמְלוֹךְ עָלֵֽינוּ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד

. בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, הַמַעֲרִיב עֲרָבִים

Living and enduring God, be our guide now and always.

Blessed are You, Source of All being, Who makes evening fall.

(This is the translation which appears in the prayerbook which my friend Reb Jeff assembled. Here's another Reform rendering.)

We began by looking at a few small details of the prayer very closely. First, the two-word phrase which usually serves as the name of the prayer, מַעֲרִיב עֲרָבִים / ma'ariv aravim, often translated as "Who Brings the Evening." The Hebrew word erev means evening, and it comes from the same root as ma'ariv, so there's a doubled root in the prayer/poem's title. That three-letter word root can also mean to mix a mixture of one thing and another. The doubled root in that one phrase acts as an intensifier, and it also hints at all of the root's other meanings -- the meaning of mixing, for instance, evokes how the twilight is created by mixing up a bit of afternoon with a bit of nightfall. Isn't that a gorgeous metaphor for what evening is?

We looked at the prayer's visual prosody on the page (which is to say, its shape -- how is the poem-shape different from seeing the same words in a block of prose text?) and at some of the prayer's repeated rhythm and syntax. We talked about different ways of translating a few of its phrases and how those different translations change our experience of the prayer (and how each of thos renderings is contained and implied within the Hebrew of the prayer -- that gets back to some of what Rabbi Marcia Prager discusses so thoroughly and lovingly in her book The Path of Blessing.) That led us into a conversation about translation and a conversation about what makes poetry poetry -- including (though not limited to) tight and careful use of language, and words which operate on multiple levels at once.

I gave them an excerpt from the article The God Who ‘Evenings Evenings’: Doubled Nouns and Verbs Give Hebrew a Unique Poetry, by Philologos, in The Forward -- which I had intended to read together, but our conversation was flowing so well that I didn't want to stop and shift modes into the purely discursive. So we moved right on to Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael's variation:

Evening the Evenings

Sacred words even the evenings

Wisdom opens gates locked around our hearts

Asher bid-varo ma'ariv aravim

B'chochmah potay'ach sh'arim.

Evening, the evenings

evening the frayed edges of our lives;

Ma'ariv aravim, amen.

Understanding alters with the times

Changing seasons, cycles divine;

U- vitvunah m'shaneh e-tim

u-machlif et ha-z'manim.

Paint diamonds on the canvas called sky

Sooth our souls with a lilting lullaby;

U-misader et ha-kochavim

B'mishm'rotayhem ba-rakiah kirtzono.

Rollin', rollin' into the night

Rollin' rollin' away the light;

Golayl or mip'nay choshech,

golayl hoshech mipnay or.

Spirit of the Night we bless Your Name

Eternal light, Eternal flame;

Ayl chai v'kayam tamid yimloch ah-laynu

L'olam va-ed.

-- Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael

Part of what interested my group about this rendering is how Rabbi Raphael pairs each Hebrew couplet (from the classical prayer) with two English lines which riff off of the same meanings. For instance, the first lines, "Sacred words even the evenings / Wisdom opens gates locked around our hearts" -- it's not a direct translation of the first line of the prayer (that would be something like, "Who with His word evens/mixes the evenings, and with wisdom opens [heaven's] gates"), but it works with the same ideas and themes. Or "Paint diamonds on the canvas called sky" -- it's not a direct translation of the prayer's lines about God ordering the stars in their appointed paths through heaven's dome, but it's clearly a metaphorical rendering of the same idea.

This also sparked an interesting conversation about how each of us tends to use the siddur in shul: do we read the Hebrew words fluidly and fluently? do we read the transliteration? do we read the English translation (and if so, do we read it with awareness of what the Hebrew actually means, or are we reading it on its own merits as an English prayer)? do our eyes leap back and forth between Hebrew (or transliterated Hebrew) and English? What's the impact -- visually, poetically, prayerfully -- of Rabbi Raphael's choice to pair English couplets with transliterated couplets?

Next up was a prose version from the 1945 Reconstructionist Prayer Book, adapted to appear in Kol Haneshanah Reconstructionist Daily Siddur. Reading this one after paying attention to the poetry of the previous versions was a little bit comical -- it does have its own appeal, but it's so very prosaic, in both senses of the word! Here it is:

Praised are you, God, ruler of the universe, who has ordained the rhythm of life. The day with its light calls to activity and exertion. But when the day wanes, when, with the setting of the sun, colors fade, we cease from our labors and welcome the tranquility of the night. The subdued light of the moon and stars, the darkness and the stillness about us invite rest and repose. Trustfully we yield to the quiet of sleep, for we know that, while we are unaware of what goes on within and around us, our powers of body and mind are renewed. Therefore, at this evening hour, we seek composure of spirit. We give thanks for the day and its tasks and for the night and its rest. Praised are you, God, who brings on the evening.

One of the women around the table raised the question of: who's excluded by this prayer? Her answer: those who don't yield to sleep; those who have trouble sleeping; those who are woken frequently by personal or medical need. (Personally, I kept getting caught on how difficult it is to pray this paragraph aloud: "when, with the setting of the sun, colors fade, we cease from our labors and welcome the tranquility of the night" -- that's just too many apposotive phrases for my taste.)

Then we moved to two contemporary poems which we read in conjunction with the Hebrew prayer we'd just studied. The first is by Jane Kenyon, may her memory be a blessing. This is one of my favorite poems, by one of my favorite contemporary poets:

Let Evening Come

Let the light of late afternoon

shine through chinks in the barn, moving

up the bales as the sun moves down.

Let the cricket take up chafing

as a woman takes up her needles

and her yarn. Let evening come.

Let dew collect on the hoe abandoned

in long grass. Let the stars appear

and the moon disclose her silver horn.

Let the fox go back to its sandy den.

Let the wind die down. Let the shed

go black inside. Let evening come.

To the bottle in the ditch, to the scoop

in the oats, to air in the lung

let evening come.

Let it come, as it will, and don’t

be afraid. God does not leave us

comfortless, so let evening come.

--Jane Kenyon

I've used that poem before during evening services, and I think of it as liturgical, although I don't think it was written for specific liturgical purpose. My group on Friday talked about how Kenyon draws on all kinds of everyday imagery -- not just the cricket rubbing its legs together, or the woman knitting (both of which have a certain pastoral quality) but even the bottle in the ditch, a piece of trash by the side of the road. We talked about the impact of the repeated word "let" -- submission, surrender -- and we talked about what it feels like to reach the mention of God at the end of the poem. (Intriguingly, Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael doesn't mention God until the end of her poem/prayer/song, either.) I mentioned that "God does not leave us / comfortless" strikes me as a reference to Everett Titcomb's setting of "I will not leave you comfortless" [YouTube link].

And we closed with a new poem of mine, which I posted here last week, and which I wrote specifically for the purposes of this class -- I wanted to be able to offer another contemporary poem which was written explicitly as a variation on the ma'ariv aravim prayer, and since I hadn't written one before, I took this as an opportunity to do so. Here it is again:

Autumn Nightfall

You mix the watercolors of the evening

like my son, swishing his brush

until the waters are black with paint.

The sky is streaked and dimming.

The sun wheels over the horizon

like a glowing penny falling into its slot.

Day is spent, and in its place: the changing moon,

the spatterdash of stars across the sky's expanse.

Every evening we tell ourselves the old story:

You cover over our sins, forgiveness

like a fleece blanket tucked around our ears.

When we cry out, You will hear.

Soothe my fear of life without enough light.

Rock me to sleep in the deepening dark.

--Rabbi Rachel Barenblat

The group noticed the watercolor imagery (my attempt to evoke the Hebrew mixture-implications of ma'ariv aravim), and I explained how the third stanza works with imagery from the verses v'hu rachum y'chaper avon which we read at the very beginning of a weekday evening service, right before the bar'chu and this prayer.

All in all: it was a really sweet hour. I'm so grateful to have had the opportunity to dip into some of the poetry of our liturgy with willing and enthusiastic fellow-conversationalists. And I'm already pondering what we might do next month...

Photo source: from my flickr stream.

October 25, 2013

Susan Katz Miller's Being Both

I've just finished Susan Katz Miller's Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family. This is a book which pushed some of my buttons, nudged against some of my boundaries, and left me with a lot to ponder. Miller writes:

I've just finished Susan Katz Miller's Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family. This is a book which pushed some of my buttons, nudged against some of my boundaries, and left me with a lot to ponder. Miller writes:

"[T]he majority of American children with Jewish heritage now have Christian heritage as well. In other words, children are now more likely to be born into interfaith families than into families with two Jewish parents. And Jewish institutions are just beginning to grapple with that fact. // Some Jewish leaders still call intermarriage the 'silent Holocaust.'... [But] many now call for greater acceptance of Jewish intermarriage in the face of this demographic reality."

Given the flurry of communal response to the recent Pew study A Portrait of Jewish Americans (my response, in brief, is Opportunity Knocks in Pew Results; I also recommend Rabbi Art Green's From Pew Will Come Forth Torah) this book could hardly be more timely.

It's no surprise that an increasing number of Jewish children have dual-heritage backgrounds. What is surprising in this book is right upfront in the title: this book articulates the perspective that all paths open to interfaith families are legitimate ones, including rearing children "as both." Here's Miller again:

"Some of us are audacious enough to believe that raising children with both religions is actually good for the Jews (and good for the Christians[.]) ...The children in these pages have grown up to be Christians who are uncommonly knowledgeable about and comfortable with Jews, or Jews who are adept at working with and understanding Christians. Or they continue to claim both religions and serve as bridges between the two. I see all of those possible outcomes as positive."

Conventional wisdom in the American Jewish community has long been that rearing children as "both" will inevitably lead to confused or rootless children, and to assimilation and to the disappearance of the Jewish people as a whole. My anecdotal sense is that American Christian responses to intermarriage have been different from Jewish ones, though there are asymmetries which shape those different responses.

Christianity has roots in Judaism, so it's fairly easy for Christians to consider Jews as spiritual "family." For Jews, relationships with Christianity are often fraught. I joke that the Christian scriptures are the "unauthorized sequel" to our holy text, which usually gets a laugh from Jewish audiences, though there's truth to the quip; there are times when Christian reinterpretation of Jewish text and practice can feel like cultural appropriation. It's also easier for a majority culture to welcome minority outsiders than for a minority culture to welcome members of the powerful majority. For those of us in minority religious traditions, there's historically been an instinct to stay insular -- for reasons I wholly understand, although I don't always like the results.

What this means in practice is often that the Christian side of the family, or the Christian community writ large, is welcoming of an intermarried couple; the Jewish side of the family, or the Jewish community writ large, can be less so. (Though that's changing, which I applaud. For instance, the congregation which I serve openly seeks to welcome interfaith families.) Regardless, when children are born to an interfaith couple there tends to be an insistence that they choose one tradition in which to rear those kids. This book offers a different perspective. Miller writes:

The vast majority of books on intermarriage have focused on the challenges of interfaith life. While I am well aware of these challenges, in this book I set out to tell a different side of the story: how celebrating two religions can enrich and strengthen families, and how dual-faith education can benefit children.... I think being both may contribute to what the mystical Jewish tradition of Kabbalah calls tikkun olam -- healing the world.

Being both might contribute to tikkun olam: now there's a chutzpahdik assertion.

Miller writes, "Children, whether or not they are interfaith children, go out into this world and make their own religious choices." Miller is herself the daughter of an intermarriage. She was reared Jewish, though she encountered some push-back from sectors of the Jewish community which don't honor patrilineal descent. She writes:

I believe my parents made the right choice for our family in that time and place. In the 1960s, when intermarriage was still unusual, without the possibility of finding or forming a comunity that would support them in giving their children access to both religions, they made a necessary and logical decision. I experienced the benefits of being given a single religious identity but also the drawbacks.

In a different era, in a different place, faced with the same decision, I have made a different choice. I am raising my children as interfaith children, educating them in both of their cultures, in both of their religions.

I particularly enjoyed Miller's descriptions of her early married life in West Africa. (As longtime readers know, my family also has a West Africa connection; my husband Ethan used to live in Ghana, and when our son was welcomed into the world we gave him a Ghanaian name along with English and Hebrew ones.) Anyway, after some years of living abroad in both Senegal and Brazil, Miller had reached a place where, she writes:

I began to understand that all religions have syncretic elements, in that they continue to evolve and change and influence each other -- even Judaism. And I began to resist the idea that this blurring of boundaries, this religious layering, threatens the well-being of practitioners. It may threaten institutions, but that's another story.

That puts me in mind of some of what I've heard Rabbi Irwin Kula teach about the impact of "mixers, blenders, benders and switchers" in today's religious world. An increasing number of Americans are tinkering with religious identity in ways which aren't one-size-fits-all. This might mean bridging or changing within the big tent of a single tradition (e.g. a Jewish family which changes affiliation from one stream of Judaism to another) or across different traditions (as in any interfaith marriage.) Countless Jews and Christians maintain meditation or mindfulness practices, even if they don't self-identify as Buddhists. Religious categories have become more permeable than they used to be. And, as Rabbi Kula notes, this shift brings with it both some loss, and the potential for a "richer and better world."

Miller's argument that this "religious layering" doesn't damage practitioners though it may damage institutions dovetails with conversations I've been having with colleagues in the wake of the Pew report. (For instance: as rabbis, to what extent is it our job to serve existing institutions, and to what extent is it our job to serve God and to serve Jews wherever they are -- or, perhaps, to serve humanity regardless of religious affiliation or lack thereof?) In this world of "mixing, blending, bending and switching" -- in this world of what Jay Michaelson calls 'iSpirituality' -- people are taking ownership of their spiritual lives, making connections and choices and building bridges, in ways which would have been impossible a century ago. Mainstream Jewish institutions may argue that it's wrong (or impossible) to rear a child as "both," but the families in Miller's book would disagree.

While the historical and sociological material in the book is interesting (and is, I think, new -- I think this is the first substantive reporting which takes into account the perspectives of children reared in explicitly interfaith settings), I'm most interested in Miller's reflections on her own experiences and choices. She writes:

I wanted my children to be able to understand their Christian heritage, to be educated about and comfortable with Christianity in a way I had never been. I also knew I wanted them to be educated about their Jewish heritage, and to have a positive relationship with Judaism. I did not want them to feel that they were trying to 'pass' as Christians. And a more universalistic pathway, such as Baha'i or Unitarianism, seemed to ignore the detailed funk and grit of our two family traditions.

I like that line about the "detailed funk and grit," which speaks to some of my own discomfort with Unitarian Universalism even though I am a principled universalist. Miller and her family wound up joining the Interfaith Families Project of Greater Washington. About that choice, she writes:

When I found IFFP, I found the community that I myself had been searching for all my life: A community where interfaith marriage was the norm. A community where no one would challenge my right, or the right of my children, to claim Judaism. A community where people with patrilineal and matrilineal Jewish heritage had equal standing. A community where I could safely explore the role that Christianity has played in the history of Judaism and in my family. A community where my husband and I could feel equally respected, where neither of us would feel like a guest. And finally, a community where I felt my family could be at the center, rather than on the periphery.

The need for interfaith families to be "at the center, rather than on the periphery" is something which I suspect Jewish leaders, even those of us striving to create open and welcoming and interfaith-friendly congregations, haven't though enough about. (There's a poignant quote about that need from Rabbi Nehama Benmosche later in the book, as well: "From a queer perspective, I know there's a difference between being accepted by the majority and being in a position where you are the majority," says Rabbi Benmosche.)

Here's the prayer with which the Interfaith Families Project's gatherings begin. It was written by Cantor Oscar Rosenbloom, who used to serve the Interfaith Community of Palo Alto:

Reader: We gather here as an Interfaith Community

To share and celebrate the gift of life together.

All: Some of us gather as the Children of Israel

Some of us gather in the name of Jesus of Nazareth

Some of us gather influenced by each

Reader: However we come, and whoever we are

May we be moved in our time together

To experience that sense of Divine presence in each of us

Evoked by our worship together

All: And to know in the wisdom of our hearts

That deeper unity in which all are one.

My reactions to that prayer are many and complex. I applaud the post-triumphalism inherent in "that sense of Divine presence in each of us" and "to know in the wisdom of our hearts / that deeper unity in which all are one." And yet I recognize that this prayer really pushes some boundaries -- as does the very fact of communities which identify as interfaith, not either/or but both/and. (Interesting related reading which also crossed my desk while I was writing this post: Rabbi Charles Arian's Christians and Jews: Praying Together With Integrity.)

My teacher Reb Zalman (Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi) teaches that each religious tradition is a vital organ in the body of humanity. We need each to be what it most uniquely is -- were the heart to try to be the liver, or the lungs attempt to serve as the stomach, we'd be in trouble! But we also need each to be connected to and in conversation with the others. It's no longer useful (if indeed it ever was) to try to live in a world where one organ thrives at the expense of another, or where one organ tries to subsume another. I love that teaching. I share it as frequently as I can. The question, of course, is whether the bold interfaith communities which Miller describes are a dangerous blending (the heart trying to be the liver, as it were) -- or a new evolution of spiritual life, an interweaving in ways which can strengthen and enrich the whole. It seems to me from her descriptions that these interfaith communities are not one thing pretending to be another -- this isn't, for instance, Christian proselytizing masquerading as Jewish practice. I think these communities which are choosing to identify as "both" are something unprecedented and new.

In the interfaith experience Miller chronicles, there's a de-centering of individual tradition, a sense in which any religious experience is already part of a broader pan-religious context. I think that's actually true for all of us in the modern liberal-religious world -- but most of us don't enter into dialogue with other traditions quite so intentionally. I grew up learning Jewish prayers and practices in synagogue and at home, and Christian prayers and practices at school and in the broader world. Is the difference between that, and what Miller describes, a difference of degree or of kind? Of course, in my own upbringing I knew which prayers and practices were "ours" and which were "theirs," and I'm not sure that's a distinction which makes sense to kids growing up in the interfaith communities Miller describes. But I think the communities she describes may foreground and make explicit something which all of our families navigate, whether interfaith or single-faith: the process of navigating the boundaries, connections, similarities, and differences between and among different religious paths in an increasingly interconnected world.

In today's world most of us navigate communal boundaries as a matter of course. Outside of communities which are intentionally insular, we all interact with people from other religious cultures. As a rabbi and as a mom, I think a lot about how best to educate kids (and adults!) about the existence and value of different spiritual paths while also giving them a deep grounding in the richness of the Jewish path we've inherited. (This winter, for instance, I'm bringing friends who serve in a variety of traditions -- Christian, Muslim, Buddhist -- to talk to my b'nei mitzvah students.) I think it's valuable to know people who are part of other religious traditions, to have lifelong relationships with people who are walking different spiritual paths, to recognize that "our way" (whatever that way is) isn't the only way. I'm not entirely comfortable with all of the choices which Miller describes -- but I can see that those choices come bearing certain gifts, and that one of those gifts is a comfort level with and a consciousness of different paths toward God.

And I think that today's world is increasingly characterized by transcending binaries which had previously seemed oppositional, and bridging communities which had previously seemed wholly distinct. Miller argues that families who choose an explicitly interfaith identity are bridging religious divisions. Is that qualitatively different from other bridging of divisions which is taking place in other spheres?

Miller writes:

From a cultural point of view, of course, it is true that straddling two cultures is not the same as total immersion in one. Often, this is what people are referring to when they fear that teaching two religions will 'water down' the experience. Being raised in one religion does have benefits -- the main one being the strength and depth of identification with that faith. Those of us choosing both recognize that our children will not have this experience...

I like to use the metaphor that we are giving our children two roots, not leaving them rootless. The children of two Italian Catholics have one deep, thick cultural root to stabilize them. An interfaith child has at least two religious or cultural roots, by definition. If parents choose to nurture them, there will be two substantial roots the child can draw nourishment from.

I think this is a valuable book for both Jewish and Christian clergy to read. For Christian clergy it may open up new ways of thinking about Judaism and about preserving Jewish practice and tradition in a mixed-faith household. And for rabbis who serve increasingly varied and variable communities -- including a steadily-growing number of families with two or more religious heritages -- this book could spark substantive conversations which could help us both to refine our own positions, and to better relate to the people we serve. No matter

where our personal lines are (do we or don't we officiate at interfaith

marriages; under what sorts of circumstances; and so on), most of us

serve in communities where dual-heritage families are increasingly

common. The people we serve may not be explicitly making the choice

Miller describes, but there are ways in which every dual-heritage family

faces some of these challenges (and is, perhaps, open to some of these blessings.)

It's clear to me from reading the book that these ardently interfaith-identified families -- adults, children, and adolescents alike -- are making active choices to take their religious background(s) and practice(s) seriously. These interfaith families are approaching their worship lives, their educational lives, and their moments of lifecycle transition with thoughtfulness. This is not the path of least resistance; this is a path which requires tremendous investment of energy.

At one point in the book, Miller compares interfaith kids to "third culture kids" -- children reared in one country who come from another country, and as a result are uniquely able to bridge between their culture of origin and the culture in which they are reared. (That concept rang a bell for me right away -- Ethan's written about it in the context of homophily and xenophilia. Go and read his book Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection.) There are ways in which interfaith kids can be natural bridges between religious communities. And maybe that gets back to Miller's tikkun olam assertion which I quoted early in this post. Miller writes:

By our very existence, strong interfaith families disarm those who believe there is only one true way to live a righteous life. By our very presence in the world, interfaith children make coexistence into a permanent reality. If the "other" is a wife or husband, if as interfaith children the "other" dwells within us, then there can truly be no "other."

It's a poignant hope. Imagine, for a moment, rewriting that paragraph with "intercultural" in place of "interfaith." Does that disarm it a little bit? And if so: what does it say that we're more comfortable with marriages and families which bridge nationalities or cultures than with families which bridge religious traditions in the ways that Miller describes?

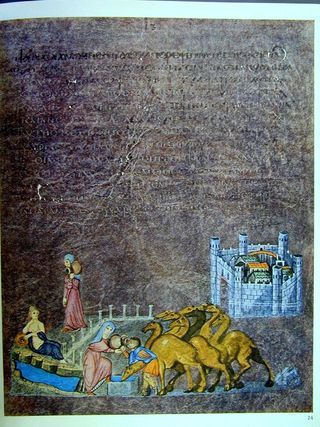

Emulating Rebecca

In this week's parsha (Chayei Sarah), Avraham sends his servant Eliezer forth to find a wife for Isaac. He offers little instruction aside from " go back to where I came from, and get a wife from there."

In this week's parsha (Chayei Sarah), Avraham sends his servant Eliezer forth to find a wife for Isaac. He offers little instruction aside from " go back to where I came from, and get a wife from there."

Eliezer -- whose name means something like "My God is my helpmeet" -- turns to God for help. He prays that God will help him find the right woman for Isaac. He says to God that when he stops at a well, if there is a woman who offers water not only to him but also to his camels, he will know that she's "the one."

Sure enough, when he stops at the well, Rebecca offers water not only to him but to his beasts, too. And he takes her back to Isaac, and they marry -- the first time in the Hebrew Bible that we read that a man loved his wife.

Giving water to a wayfaring stranger in a desert land is the bare minimum of hospitality. But offering to water a train of camels too -- that's a major undertaking.

Rebecca goes above and beyond. In her physical acts at that well, she draws on her own internal well of compassion and kindness to meet this travel-bedraggled stranger with kindness and compassion.

How can we be like Rebecca as this Shabbat approaches -- cultivating the habit of drawing forth compassion from the wellspring of our hearts, so that our natural response to everyone we meet is one of kindness and welcoming?

This is more-or-less the teaching I offered this morning at my shul's meditation minyan. The image comes from the Vienna Genesis, a 6th-century illuminated manuscript. Shabbat shalom!

These are things which have no limit

Things which have no limit in this world or the next:

a parent's tender worry cartoons in syndication

the world glinting and shattered hot tea to soothe our sorrows

sunrise following on the heels of dawn, which follows night

the eggshell blue of autumn sky this grief: another gun death

the rise and fall of breathing clock hands ticking forward

two brothers meeting at a grave their eyes rimmed red from weeping

the silence in between the words of every mourner's kaddish

the need for simple kindness on the subway platform

on the broken sidewalk on the email list-serv

your hand in mine now, warming my heart cracked clean and opened

the heavens glistening with stars waves running and returning

This poem was inspired obliquely by a lot of different things, among them the passage "these are things which have no limit" which is part of our morning liturgy; news of another school shooting; this week's Torah portion, Chayei Sarah; Hannah Szenes' poem "Eli Eli (halicha l'Caesarea)." (That link goes to a gorgeous Regina Spektor recording of the song in Hebrew; an English translation reads, "My God, my God, I pray that these things never end: the sand and the sea, the rush of the waters, the crash of the heavens, the prayer of the heart.")

October 24, 2013

Maintaining hope in the face of depression

Someone asked me recently how to maintain hope when depression is dogging one's heels.

Someone asked me recently how to maintain hope when depression is dogging one's heels.

The first thing I want to say is: no matter how isolating depression feels, you are not alone. Others have been where you are. We recognize the terrain and we recognize the tricks that depression plays on you -- the ways it makes you feel existentially solitary, disconnected, broken. We recognize, too, the way that depression tries to preserve itself. How it murmurs into your ear that nothing will ever be different -- that this is what life is and you will never feel any other way. It is lying to you.

There is help, and I urge you to take it. If you are in therapy, call your therapist. (If you're not in therapy and want a referral, ask someone local to you -- your rabbi or someone you trust.) If you are in spiritual direction, call your spiritual director. (If you're not in spiritual direction but want to explore that possibility, here's one way of finding a spiritual director; you might also reach out to one of my teachers for a referral.) Consider antidepressants or anti-anxiety medication; know that there is no "weakness" in not being able to bootstrap yourself out of depression.

Extend kindness to yourself in whatever ways you can. Try to eat well. Try to get enough sleep. For me, a hot shower and a cup of good tea are always restorative. (So is good hand lotion. I know, it sounds silly, but it really does help.) Walking outside in the fresh air sometimes helps too. Take advantage of whatever small things you can do to make yourself feel better, even if the feeling-better is only temporary. Lather, rinse, repeat. Our sages famously listed things which "have no limit" -- and though self-care isn't on their classical list, it's definitely on mine.

Recognize that depression may at times be disabling, and give yourself ample credit for any goal you set which you are able to achieve. Sometimes just getting out of bed in the morning may feel like you're trying to climb Everest from inside an iron lung. And -- this seems extra-unfair -- bear in mind that sometimes depression brings with it a kind of emotional paralysis which makes asking for help almost impossible. The depression may whisper to you that no one wants to hear from you when you're "like this" or that there's no point in seeking help. Let me say again: it is lying to you.

I heard Rabbi Jeff Roth teach years ago that if one reaches the hour for reciting the modah ani prayer for gratitude in the morning, but finds oneself unable to access the gratitude with which one wishes to invest the prayer, one can say the prayer with the intention of someday being able to feel gratitude again. I know that there are days when gratitude feels impossible to reach. I know that there are days when it feels implausible to even hope for better. On those days, know that people who love you are willing and able to hold on to that hope for you even if you can't reach it yourself.

You who are struggling with this right now: I am holding you in my prayers. If you can't believe that you will ever feel better, don't beat yourself up for that. That's not a failing on your part: it's something the depression has stripped from you. But I believe that this isn't all there is, and I believe that you will reach a better place again. If you can't believe that right now, it's okay -- I'll hold on to that belief for you until you're able to hold it for yourself again. You are loved by an unending love: not only when you are healthy, but also when you are sick; not only when you are optimistic, but also when you feel the way you feel now.

May you find comfort, speedily and soon.

Image source: wikimedia commons.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers