Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 179

September 11, 2013

New poem for Yom Kippur: We Are Jonah

I'm immersed this week in preparing -- logistically, emotionally, intellectually, spiritually -- for

Yom Kippur, which begins at sundown on Friday night. I'm also working on what has been the project of

my heart for the last many months, a new machzor for the Days of Awe, which will be available (God willing) next summer

for use next year. (More about that later, when the process of revision and multilingual proofreading is complete!)

As I shift back and forth between preparing for these holidays, and working toward

next year's holidays, I've found myself working on a new poem which comes out of the book of Jonah.

(It also comes out of a beautiful midrash from the first-century Pirkei de Rabbi Eliezer, which I

cited in last year's sermon In

the Belly of the Whale.) If this speaks to you, feel free to use it -- with attribution, of course.

WE ARE JONAH

In Rabbi Eliezer's vision

Jonah entered the whale's mouth

as we enter a synagogue.

Light streamed in through its eyes.

Jonah approached the bimah, the whale's head.

Show me wonders, he said, as though

his own life weren't a miracle.

The whale obliged, swimming down

to the foundation stone,

the navel of creation

fixed deep beneath the land.

Tsk tsk, chided the fish:

you're beneath God's temple --

you should pray.

Prayer requires stillness.

Running away had always been

so easy. Sitting silent

in self-judgement -- forget it!

But waves only churn the surface.

In the deep beneath the deep

Jonah was wholly present.

We all flee

from uncomfortable conversations

the drip of a hospital IV

the truths we don't want to own

the work we don't want to do.

Now we're in the belly of the whale,

someplace deep and strange.

God calls us to awareness:

to stand our ground

in the place where we are,

to do the work which needs doing.

To bring kindness and mercy

even to those who are unlike us.

Are we listening?

September 9, 2013

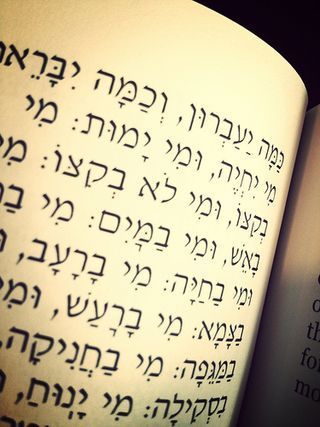

Sitting with what we can't know: on "who will live and who will die"

This morning I was asked a question about the Unetaneh Tokef prayer which we pray on Rosh Hashanah. How do we make sense of "on Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed" when something truly awful happens? For instance: a teenager is killed, God forbid, in a horrific accident. How can we reconcile our horror at this kind of trauma with a sense of a loving God? What does it mean to assert that God "seals" such a fate for us? Let me say upfront that I don't have "the" answer. But here is an answer.

This morning I was asked a question about the Unetaneh Tokef prayer which we pray on Rosh Hashanah. How do we make sense of "on Rosh Hashanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed" when something truly awful happens? For instance: a teenager is killed, God forbid, in a horrific accident. How can we reconcile our horror at this kind of trauma with a sense of a loving God? What does it mean to assert that God "seals" such a fate for us? Let me say upfront that I don't have "the" answer. But here is an answer.

Earlier in that same prayer, we read "You open the Book of Memory. It reads from itself and the signature of every human being is in it." That line says to me that we're not talking about God as some kind of cosmic accountant, taking note of each action and selecting a corresponding fate. (This isn't Santa Claus, who "knows when we've been bad or good so be good for goodness' sake!") The Book of Memory is something we each write for ourselves.

Every action I take inscribes itself in the Book of Memory. I inscribe and seal my signature in that book with every thing I do, and every thing I don't do; every kind word I speak, and every unkind thought I harbor. God doesn't write the Book of Memory for us: we write it ourselves, and at this season of the year, it "reads from itself" -- or, to use a more modern metaphor, at this season of the year, we sit down and watch the television show of our own lives.

Later in that same prayer, we read "But teshuvah (repentance or re/turn, turning toward God), tefilah (prayer / self-examination), and tzedakah (righteous giving) avert the harshness of the decree." The prayer doesn't make the claim that these three things can change what's going to happen; but they can ameliorate it. They can sweeten it. They can soften it. If, God forbid, someone I love is going to get sick and die this year -- no amount of teshuvah, tefilah, or tzedakah on my part or on theirs will change that reality. Our cells do what they do; our bodies do what they do; and sometimes we cannot be medically made well again. Or if, God forbid, a teenager on her bicycle is struck by a car -- no amount of repentance, prayer, or righteous giving can change that shattered reality for her or for her family who remain to mourn. But teshuvah, tefilah, tzedakah can change how we experience the reality which is. They can change our experience of the world.

In between the two verses I've cited, there's the part I was asked about. How can we make sense of a God Who writes on Rosh Hashanah, and seals on Yom Kippur, who will live and who will die; who by fire and who by water; or in this day and age, as a colleague of mine dryly noted, who by peanut allergy and who by bee sting? I read this passage not as a literal description of who God is or what God actually does, but as a metaphor. What it says to me is: for centuries we have collectively needed to imagine a God Who is in charge, Who is holding the reins, Who is keeping watch over creation. A God Who takes note when someone dies by fire, and someone dies by flood. And not only how we die, but also how we live -- who will find rest, and who will wander; who will be driven, and who will be tranquil. Something in us needs to believe that God is paying attention.

This prayer's authorship is unknown, though we know that parts of it date back to the 8th century of the Common Era. (That's one thousand, three hundred years ago. This is a very old concept of God.) I suspect that its authors wrote it out of a fervent hope that God was, in fact, keeping track of who lives and who dies (and, beyond that: who dies in comfort, and who dies in trauma; who lives happily, and who lives in misery.) But after that paragraph, the prayer goes on to say that our teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah can temper the harshness of life's decrees. If it helps, we might think of the "decree" as something like karma, in which the aggregate of our actions and choices leads us to a particular future. Or maybe the "decree" is the laws of the universe: sometimes cancer cells can be conquered, and sometimes they can't. Sometimes a near-car-accident can be averted, and sometimes it can't.

And then the prayer goes on to say: "You [God] do not seek our death, rather that we turn from our ways and live." In other words: God isn't up there somewhere in the sky waiting for us to screw up so that He can strike us down! That kind of toxic theology exists in the world, but it's not a Jewish way of thinking about God. In the Jewish understanding, God is always yearning for us to make teshuvah, to turn and re-turn, to re-orient ourselves so that we are facing in the right direction again, to consider our lives and try to make better choices. No matter what we do, God always wants us back. I think there's something especially meaningful about hearing that as we begin the Ten Days of Teshuvah, the ten days of intensive repentance when we struggle to align our lives again with our highest ideals. No matter how we've missed the mark, God always yearns for us.

And then the prayer reminds us -- echoing the verses from psalm 90 which we read at funerals -- that "we are a broken urn, withering grass, a fading flower, a passing shadow, a vanishing cloud, a blwing wind, settling dust, a fleeting dream." Even our lengthiest and sweetest lives are like withering grass compared with the vast scope of the cosmos. The prayer's final line contrasts God with that description of us: we are fleeting and our lives are short, but God endures forever. I suspect that the prayer's author(s) found comfort in the idea that even though our lives are brief, there is something beyond us which endures forever, throughout all space and time, throughout all the worlds. We are temporary; God is forever; and when we enter into relationship with God (whatever we understand that term to mean), we link ourselves with forever.

What is it that is written on Rosh Hashanah, and sealed on Yom Kippur? I don't believe that God writes down every action each of us will take in the new year, and then seals the book on Yom Kippur like a vault door swinging closed. I believe that on Rosh Hashanah we are called to take the time to sit with the truth of the lives which we ourselves have written. Who am I? Who have I been over the last year? Who do I think I will be in the year to come? We're also called to sit with the uncomfortable truth that we don't know what the year will hold. Who will live, and who will die, in 5774? Who will be healthy, and who will be sick? Who will be joyful, and who will experience depression's cold fire? These are real questions, and though most of us ignore them most of the time (who can live in constant awareness of everything we don't know about our own futures and our own mortality?), during these ten days we're called to sit with what we can't know.

The purpose of this prayer, for me, is its emotional journey. It takes me from "I am writing the book of my own memories and my own life," to "I don't know what the coming year will hold, but every life contains death and suffering," to "I can sweeten my experience of these realities through teshuvah, tefilah, tzedakah -- through trying to live in a mindful, thoughtful, just way." And then it takes me to its final stop: "my life is brief, but God is forever, and in my moments of greatest awareness, I can touch that forever-ness." At the moment of a birth -- or when I am awestruck by a sunset or a snowfall -- or when I sing to someone while they are dying -- I connect with God. I touch infinity, just for an instant.

I still experience sorrow. I am still mortal, and so are those I love. And terrible things still happen: they could happen to me, they could happen to my loved ones, they could happen to hundreds or thousands of people. But when I try to live with teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah, I strengthen myself; I root myself; I make myself more able to face not only the times when life is bitter, but also the times when life is sweet.

Related reading:

Need a Reason to Repent? The Answer—No Matter Who You Are—Can Be Found Here, by Helen Plotkin, in Tablet magazine (2013)

Every day I write the book, from my own archives, posted here in 2005

September 6, 2013

Waiting for us to come home

In lieu of a sermon last night, I shared a handful of Rosh Hashanah poems. One of them is brand-new, and here it is. It is inspired by (or perhaps is a remix / adaptation of) Rabbi Margaret Moers Wenig's sermon God is a Woman and She Is Growing Older.

Waiting for us to come home

God sits in her kitchen

with her gnarled hands folded.

She doesn't needlepoint much anymore.

She's waiting for us to knock.

We always forget the door is already open.

God remembers when each of us was born.

God remembers when creation was born.

Closing Her eyes and touching that place

deep inside, the swirling void

within which all life was grown.

God remembers every child She has lost.

God remembers every time

one of us has been unkind. Each night

she lights memorial candles across the heavens,

our souls remembered across the sky.

God wants to say: it's okay that you didn't write.

It's okay that you didn't call.

You stayed away because you didn't want

to disappoint Me. You could never disappoint Me.

Do you know that I still love you?

God sings lullabies to us, rocking us

even though we don't think we fit in her lap any more.

We blink and old mama God is transformed.

Her creaky kitchen chair is a throne,

her house dress an ermine robe.

How often do we sit here in shul

reciting prayers we didn't write, signing postcards

and dropping them in the mailbox

instead of coming home? God is waiting

for us to come home.

September 5, 2013

Creating Community (A sermon for Rosh Hashanah morning)

For the building will be constructed from various parts, and the truth of the light of the world will be built from various dimensions, from various approaches, for these and those are the words of the living God... It is the precisely the multiplicity of opinions which derive from variegated souls and backgrounds which enriches wisdom and brings about its enlargement.

That's Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine, known colloquially as Rav Kook. Let me say part of that again:

For the building will be constructed from various parts, and the truth of the light of the world will be built from various dimensions, from various approaches, for these and those are the words of the living God...

We might reasonably ask: what is Rav Kook talking about here? What is "the building"?

Often in Jewish tradition when we hear reference to a building, especially when it sounds like it might be a Building-With-A-Capital-B, the text is speaking of the Temple. The first Temple was built in Jerusalem in 957 BCE, and was sacked by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. The second Temple was begun some fifty years later; it was sacked by the Romans in the year 70 (C.E).

But Rav Kook is speaking in the future tense, about something which will be built. He might mean the Third Temple -- for which, I should note, the Reform movement officially does not yearn! But the idea of a rebuilt Temple implies a time when the work of perfecting creation will be complete; the messianic era. Perhaps that's what he's speaking of. Perhaps he means Olam ha-ba, the World to Come.

But I don't think he has to be speaking about a literal construction project at all. I think he's talking about Jewish community.

[A]nd the truth of the light of the world will be built from various dimensions, from various approaches, for these and those are the words of the living God...

Just as "the building" requires many different parts, truth does, too.

"For these and those are the words of the living God." Some of y'all may remember the Talmudic story about the longstanding dispute between the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai, the two archetypal schools of Torah interpretation. Each set of scholars claimed that the law was in accordance with their own views. But then a bat kol, a voice from heaven, announced Eilu v’eilu divrei Elohim chayim, "These and those are the words of the Living God," adding, "but the law is in agreement with the rulings of Beit Hillel."

Since both these and those "are the words of the Living God,” why is the law according to Beit Hillel? Because they were kindly and modest; they studied their own rulings and those of Beit Shammai.

In modern lingo, we might call them pluralists. They accepted the possibility that someone else's interpretation might be right.

I love Rav Kook's idea that in order for truth to be built, we need all of our "variegated souls and backgrounds." The building of a community requires all of us.

This community, like Rav Kook's building, is constructed out of diverse parts. Some of us joined this congregation when it was Orthodox. Others joined when this community was affiliated Conservative. Still others joined once this community became a part of the Union for Reform Judaism. And some of us aren't officially "members" at all, at least not yet.

We all have different reasons for being a part of this community. Some of us may join because we want to educate our kids. Some of us may join because we have a spiritual thirst, and we find that davenen in this community feeds our thirst to connect with the prayers and to connect with God. Some of us, because we want to honor our parents, or because we just want to support the existence of a synagogue in northern Berkshire.

Members or not: in an existential sense we all belong here, we're all welcome here, no matter where we come from, no matter what our religious background, no matter what our personal spiritual practices may be. And the community requires all of us, all of our approaches and ideas and souls.

The first time I was called for jury duty, I was caught between exasperation and curiosity. (This may sound like a non sequitur, but bear with me.) I've been called many times since then. I've spent mornings in the courthouse, watching the videotape in which a judge speaks to us about the importance of doing our civic duty. I've answered questions about prejudices which might disqualify me from serving.

I don't hope to ever wind up on a jury, but I admire the fact that our nation's system of justice is built -- at least, in its most ideal form -- on a foundation of equality, where each of us has a part to play. Creating a just society isn't something left to the rich, or consigned to the poor. It isn't work that's permitted only to men, nor work endured only by women. No race or sexual orientation or creed exempts one from taking part. There's something profoundly egalitarian about this system. Building justice is work which all of us must do.

In our Jewish lives, too, we live in an egalitarian system. In Reform Judaism, there are no distinctions between kohen, levi, and yisrael, the ancient divisions of the Jewish people into priestly castes and ordinary folk. And in our community, people of all genders and sexual orientations are both entitled and expected to live a life of mitzvot.

Although the word mitzvah is often translated as "good deed," it means "commandment." Jewish tradition speaks in terms of positive and negative mitzvot, things we are commanded to do and not to do. Many of these are time-bound, which means they're meant to be performed within a particular span of time.

In the early traditional understanding, men were obligated to perform time-bound mitzvot; women were not. Prayer is the quintessential example of a mitzvah which is incumbent on men, but from which women were considered exempt. After all, it was presumed that we had children to care for!

As the mother of a three-year-old, I appreciate the way our sages valued the "women's work" of caring for a household and a child...but I've always chafed a bit at the corrolary that therefore, women didn't "count" in a minyan. If we weren't obligated to participate, then we couldn't be counted as participants.

That was the norm across the board in the Jewish world until 1845 when the Reform movement chose to count women for the purposes of making minyan. Today we take egalitarianism for granted in almost every liberal Jewish community. We presume that people of all genders "count." Our challenge is a different one: the challenge of standing up to be counted in the first place.

Some of us may pray daily. And some of us even maintain a practice of daily liturgical prayer, using the words in the siddur. But for most of us, spiritual practice is the item which falls off the to-do list when times get busy. And even if we do make time to meditate or to daven, we tend to do it alone, on our own time.

Solitary prayer and meditation are wonderful. And they're a longstanding part of Jewish tradition. But the mitzvah of daily prayer, as it's classically understood, is specifically an obligation to not be alone. It's an obligation to come together in community. Phrased another way: it's an obligation to make a minyan, a quorum of ten.

Prayers which involve a call-and-response are traditionally only recited when ten are present. One is the bar'chu, the call to prayer. One is the kedusha blessing of the Amidah, which begins n'kadesh et shimcha ba-olam, "Let us bless Your name throughout the world!" And one is the prayer we've come to know as Mourner's Kaddish.

From my teacher Rabbi Daniel Siegel I learned about the beautiful practice of standing next to a mourner so that the mourner knows that they are being heard. Listening, and responding with amen and with the refrain y'hei shmei raba m'vorach, becomes an active act. The kaddish is a kind of duet, a collaboration, created through the mourner's speech and the community's response.

And traditionally, it requires ten adult Jews in the room.

Can kaddish be recited alone? I know mourners who have prayed the kaddish alone and have found comfort in the ancient cadences. I have recited mourner's kaddish with fewer than ten adult Jews in the room, and the prayer still had meaning for me and for them.

But I think that when our sages mandated that the mourner's kaddish be recited with a minyan, they were on to something. They understood that there is meaning, for a mourner, in being surrounded by the loving embrace of community and saying these ancient words to listening ears. And there is meaning, for a community, in together creating the container within which members can safely mourn.

When I was a student chaplain, I came to feel that my primary job was to listen. When I listened with my whole attention, God listened in and through me. The same is true when a mourner is reciting kaddish. We are God's listening ears; we are God's compassionate embrace. This is a mitzvah; a commandment; an obligation.

We may chafe at that notion of obligation. "Most of us feel constrained or burdened when we hear this word, as though freedom is now constrained and happiness compromised," writes Rabbi Irwin Kula. "But in fact, when we heed our obligations, take responsibility for our decisions, place our duties for others before our immediate satisfactions, we actually are happier as a result."

Some of us may push back: commanded by Whom? I'm not sure I believe in God, so how can I be commanded? Others may say, that's not what religious life is about for me. I come to synagogue for spiritual satisfaction, or to honor those who have died, but not because of any "commandments." Or, perhaps: I join the synagogue to support Jewish community, but that doesn't mean I'm "commanded."

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas argued otherwise. For Levinas, the most important thing is not the self but the other, which is to say, other human beings. Levinas taught that when we allow ourselves to truly meet someone else, we encounter a "trace of God."

When Moses asked to see God's face, God replied that no one could look upon divinity and live. So God placed Moses in the cleft of a rock and passed by him, and Moses saw the divine afterimage. For Levinas, that afterimage of God is present when we truly see each other as whole human beings. In meeting and honoring the other, he said, we encounter God.

And we become responsible to each other. For Levinas, that's what it means to be metzuveh, commanded. Rabbi Ira Stone writes, following Levinas, that "The beginning of ethics is holding the door for another person and saying, Apres vous." In order to lead an ethical life, one needs to hold the door open for the other. To notice that the other needs you, and to be there for them as you are able.

Rabbi Simcha Zissel, who lived in the late 1800s, taught that "one of the methods by which the Torah is acquired is by carrying the burden with our fellow." This is the Jewish path. We reach enlightenment, you might say, by schooling our lives in practices of being responsible to each other. Even more: this is how we cultivate joy.

And how do we do that? By showing up. At naming ceremonies and b'nei mitzvah, weddings and funerals -- preparing meals of celebration, and meals of consolation -- learning and growing together -- feeding the hungry together -- and helping each other fulfill the mitzvah of saying kaddish with a minyan.

We read in Pirkei Avot, the Ethics of the Fathers, that "When two sit together and discuss words of Torah, the Shekhinah, God's Presence, is present with them." Surely God is found in our gatherings even when we are as few as two.

But a gathering of ten feels qualitatively different from a gathering of two. Imagine setting a dinner table for ten and having only one or two guests show up: you might still have a wonderful time, and you'd have plenty of leftovers, but it's not the same. Beyond that, there's something important about understanding ourselves as ethically, and spiritually, obligated to each other.

"Once the other has called us," writes Rabbi Ira Stone, "once we have fallen in love, we are enjoined to a life of never-ending responsibility." As a parent, I've come to understand this deeply. Once I came face-to-face with our newborn son, my life was irrevocably changed. I became not only Rachel, not only poet and rabbi and thinker, but also his mother, responsible to him and for him. Always.

But that same kind of responsibility inheres in all of our relationships. Each of us is responsible to, and for, each other. The fact that we come together to shoulder each others' burdens is what makes us a Jewish community. In this community we come together in this way regardless of denominational background. Whether you grew up Reform or Orthodox, whether you grew up Jewish or non-Jewish, whether you are intermarried or inmarried or single: each of us is responsible to and for each other.

I said earlier that we all belong here. All are welcome. I mean that. And belonging bears a price. I'm not talking about membership dues or high holiday donations, though obviously we appreciate everyone who's able to help us keep the roof intact and the heating bills paid. I'm talking about presence.

Every day is a spiritual barn-raising, in Jewish tradition: an opportunity for people to come together and help each other with something none of us can do alone. One could say, echoing the famous dictum, "no man is a minyan." No person can make community for herself or himself alone.

As a pluralistic community, a community with roots in all three of the major denominations of contemporary Judaism, we have a unique opportunity to work together to create a life of learning, a life of celebration, and a life of prayer, a big tent beneath which we can all be sheltered. Like jury duty -- see, I told you I'd get back to that! -- this is work which we all must do.

Over the course of 5774, we'll do some learning here about minyan, kaddish, and what it means to build community -- starting with a two-part class on kaddish and minyan which I will teach along with Rabbi Pam Wax next month.

"Davening in a minyan," writes Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, "reminds me that no person is an island. It gives me a much stronger feeling of K'lal Yisrael, the greater body of the people Israel. Each of us is a link in a chain of tradition that stretches back thousands of years. The God of my ancestors becomes more real to me in shul."

Here's a secret, already known to those who come here on Saturday mornings: our Shabbat services are short and sweet, a mere 90 minutes long. They are rabbinically guaranteed to enrich your life, lower your blood pressure, and connect you with those around you. And, as my beloved teacher Reb Zalman points out, each of us is a cell in the body of K'lal Yisrael. When we come together, we are more than the sum of our parts.

Whether you show up every week, or once a month, or half a dozen times during the year, your presence is a twofold gift. You get 90 minutes to sing, pray, and relax. And you're constituting community by showing up for someone who needs to mourn...so that when it's your turn to mourn, there's a strong and healthy community to be there for you, too.

Though this isn't just about ensuring that ten are present to surround and comfort those who mourn. It's about stepping up to be an active participant in creating community. Torah teaches that we are called to be a mamlechet kohanim, a nation of priests. Connecting with holiness, striving to imbue our lives with meaning, creating community: these aren't tasks we delegate to a hereditary caste of priests. They're not even something we delegate to our rabbis. These are everyone's task.

In Reform Judaism, we often privilege informed choice over the accumulated decisions of our sages. We may think of ourselves as choosing Jewish practice, rather than being born into it or obligated to it by default. But we can choose to be obligated to each other. We can choose to understand ourselves as co-creators of something intricate and beautiful. Together, we weave the tapestry of our community. And that requires all of us. If one person doesn't show up, doesn't bring their thread, then there's a hole in the tapestry where that thread is meant to be.

Earlier this year I had the opportunity to study the work of a Harvard-trained Israeli happiness expert named Tal Ben-Shahar. He writes:

Many people believe that the key to a successful relationship is finding the right partner. In fact, however, the most important and challenging component of a happy relationship is not finding the one right person -- I do not believe that there is just one right person for each of us -- but rather cultivating the one chosen relationship.

This is true of spiritual life, too. No religious community is perfect...including this one. You may find that there's something we do here which you wish we didn't, or something we don't do which you wish we did. There may be someone here who pushes your buttons, or something that doesn't quite meet your expectations.

But being part of a congregation is like being in any relationship. What matters is that you choose the relationship and cultivate it. And, as in any relationship, the blessings you receive in return will be proportional to the amount of your investment. Again, I'm not talking fiscally; I'm talking about soul and heart.

Rav Kook wrote that the building will be made from various parts, and the truth of the light of the world will be built from various approaches, various souls and backgrounds.

This community needs each of us. Not despite our differences, but because of them. It's in and through our differences that we can know ourselves to be part of a much greater and more vibrant whole.

September 4, 2013

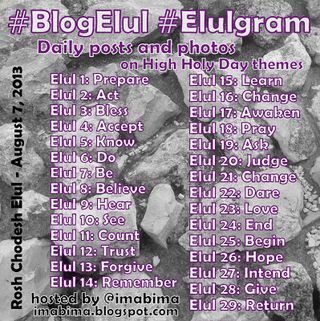

#BlogElul 29: Return | an #Elul poem about #teshuvah, and thoughts on returning

RETURN

How to make it new:

each year the same missing

of the same marks,

the same petitions

and apologies.

We were impatient, unkind.

We let ego rule the day

and forgot to be thankful.

We allowed our fears

to distance us.

But every year

the ascent through Elul

does its magic,

shakes old bitterness

from our hands and hearts.

We sit awake, itemizing

ways we want to change.

We try not to mind

that this year’s list

looks just like last.

The conversation gets

easier as we limber up.

Soon we can stretch farther

than we ever imagined.

We breathe deeper.

By the time we reach the top

we’ve forgotten

how nervous we were

that repeating the climb

wasn’t worth the work.

Creation gleams before us.

The view from here matters

not because it’s different

from last year

but because we are

and the way to reach God

is one breath at a time,

one step, one word,

every second a chance

to reorient, repeat, return.

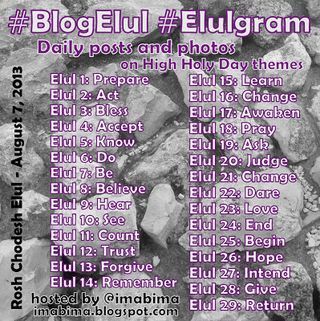

This poem was written in 2005, and served as my Elul card that year. (You can find all of the Elul / New Year's poems I've written over the years at the page VR New Year's Poems.) It seemed an apt way to close out my experience of blogging #blogElul this year.

This poem was written in 2005, and served as my Elul card that year. (You can find all of the Elul / New Year's poems I've written over the years at the page VR New Year's Poems.) It seemed an apt way to close out my experience of blogging #blogElul this year.

Every year during this season we focus on our work of teshuvah, of turning and re-turning to orient ourselves toward God. As one of my favorite prayers of the season goes, "Return again, return again, return to the land of your soul." (The melody I know is by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, z"l; I'm not sure whether or not he also wrote the words.) "Return to who you are, return to what you are, return to where you are born and reborn again..."

Every year we reorient, repeat, return. Every year the work is the same because it is human nature to need to make teshuvah: daily, weekly, monthly, annually. We are always human, we are always missing the mark, we are always needing to return. Every year the work is different because we are different. We bring this year's version of our selves to the work at hand.

I wish you every blessing in the continuing work of teshuvah, of returning to our Source, returning to God, turning yourself around again so that you can feel in your heart and know in your mind that you are on the right path again. May we all be blessed to return to where we need to be.

Happy Rosh Hashanah, everyone. May your new year be joyous and sweet.

September 3, 2013

(Revised) Prayer for Syria

Pretty much every rabbi I know is either working on a sermon about Syria, or wondering whether we ought to be frantically scrapping an existing Rosh Hashanah sermon in order to preach about Syria, or reading voraciously to try to cultivate an informed opinion about Syria and whether the United States should intervene (or whether, perhaps, the US should have intervened eighteen months ago but has now missed its window.)

Here's a slightly different tack. I've spent some time today revising a prayer which I posted here just over a year ago. This revision is intended to be prayed aloud. In my community we'll be reciting this prayer toward the end of Rosh Hashanah services, alongside our Prayer for Israel and Prayer for Our Country. If this speaks to you, you're most welcome to use it; I ask only that you keep my name attached so that people know where it came from.

A version of this prayer / poem will appear in my forthcoming collection of Jewish liturgical poetry.

Prayer for Syria

Shekhinah, in Whose womb creation is nurtured:

when your children are slaughtered you weep.

Bring peace beneath Your fierce embrace

to Syria. Let a new image of the world be born

in which American Jews pray for Syrians, who pray

for Israelis, who pray for Palestinians, who pray

even for American Jews. Fill the hearts

of the insurgents with Your compassion

so that when the regime comes to its end

no one seeks the harsh justice of retaliation.

Awaken conscience in the Syrian government

and spark their dormant mercy. And for us:

help us to wield our power in service of good

and strengthen our resolve not to turn away.

We bless You, Source of Mercy. Bring wholeness

to this broken creation. And let us say: Amen.

#BlogElul 28: Give

To make a present of:

I give my son a toy.

To place in the hands of:

please give me the challah.

Give in. Give away.

Give off. Give back.

To accord or yield

something to someone else.

From the Old Norse.

From proto-Germanic.

From Proto-Indo-European:

"to take, hold, have..."

I give you my word.

I give all I have to give.

Accord, allow, hand over,

provide, present, vouchsafe.

Antonyms: deny, refuse,

take, withhold, keep,

neglect, receive.

That last seems wrong.

God gives; we receive.

These aren't opposites:

they're a two-sided coin.

Giving and receiving

we open up our hands.

We give to each other

blessing and forgiveness

now and forever.

The lines "Giving and receiving, we open up our hands" come from Rabbi Hanna Tiferet's beautiful Grace After Meals, V'achalta v'savata u-verachta. The various definitions of "give" come from assorted thesauri.

September 2, 2013

This year's new year's poem

This is the Elul card / approaching-new-years' card which my family sent to friends and loved ones this year. I'm sending it now to each of you. May your transition into the new year be sweet!

At three and a half, your glee

at stomping on a sand castle

is as vast as your desolation

when another kid won't share.

At thirty-eight, I seek

good novels and vinho verde

instead of chocolate-chip cookies

and Dora cartoons --

though when an email angers me

I seethe just like you do.

But if I've carved grooves

of gratitude on the soft sand

of my heart, my tempests drain.

I can calm my own sea.

The sages of the Talmud say

if we teach you Torah

and how to make a living

and how to swim

then our work here is done.

I want to give you the Torah

of curiosity and kindness,

of noticing beauty everywhere.

The life's work of saying thanks

even for what shakes you.

The skill to navigate

your own turbulent waters,

to take deep breaths, to wake

into new reasons for gratitude.

לשנה טובה תכתבו ותחתמו!

May you be inscribed and sealed for a good year.

With love, Rachel, Ethan, and Drew

(All of my previous years' Elul poems / new year's poems are archived here: VR New Year's Poems, 2003-present)

#BlogElul 27: Intend

Does intent matter?

My inclination is to say yes, intent matters a lot. If someone steps on my foot by accident, that's different from doing so maliciously and on purpose. If someone tramples on my emotions by accident, that's different from doing so maliciously and on purpose. In this mode of thinking, I am pretty squarely aligned with Jewish tradition. In Judaism, intentions do matter.

An example: it's a mitzvah (a connective-commandment) to make a blessing over what one eats. If I make the blessing borei pri ha-etz ("blessed are You, Adonai our God, source of all being, creator of the fruit of the tree") over an apple and then eat the apple, then I'm done. If, fifteen minutes later, I decide I'm hungry for a pear too, then I make the blessing again.

However -- if when I made the blessing the first time, I had the intention of eating both fruits, then the blessing "counts" for both and I don't need to repeat it. (My gratitude for this nifty example is due to the author of the post Jewish Treats: Intentions Matter.) When it comes to saying blessings, intent matters.

The same goes for saying prayers. Saying a prayer with whole intention (usually known in Hebrew as kavanah) is a transformative act. Merely reciting words without intention isn't the same at all. The ideal is to carry out a mitzvah -- whether one of prayer, or ritual, or interpersonal interaction -- while holding on to the intent that the mitzvah should take place for the sake of good and for the sake of God. If one walks past a synagogue on the first of Tishri and happens to hear the shofar, but didn't realize it was Rosh Hashanah and doesn't listen to the sound with intention, does it "count" as having fulfilled the mitzvah of hearing shofar? The tradition's dominant answer is: nope, that doesn't count. In order to fulfill a mitzvah, you have to do it with intent. (For more on this: Kavvanah & Intention | My Jewish Learning.)

It's the season of teshuvah, repentance and return. When I think of teshuvah and intention, I think: how do intent and intention impact our need to make teshuvah? And here's where I get back to the idea with which I started this post -- that intentions matter. If I have every intention of lighting Shabbat candles, but I get sick and I can't drag myself out of bed to do the lighting: nu, that's a missing-of-the-mark, but not a big one. If I don't give a damn about lighting Shabbat candles or creating Shabbat consciousness, and that's why I don't bother to light -- that missing-of-the-mark has a different valance, a different feel. It's the difference between failing someone accidentally, and failing them because you can't be bothered to care about the relationship at all.

If I aspire -- if I intend -- to lead a life filled with mitzvot, a life of connection and consciousness, then that intention will shape my days and my choices. I'll still miss the mark, because that's inevitable! But if my intentions are good, then my mis-steps won't be so terrible. This does not mean that one can intentionally sin and then aim to make teshuvah later -- e.g. "I'll ignore this person in need, because I don't feel like being compassionate, but later I'll make up for it." Or "I'm going to say something mean, because I'm feeling spiteful toward this person, but next week I'll make teshuvah and it will be as though it never happened." That's not how it works. We don't get to intentionally sin, promising to get around to teshuvah later. That's a kind of intentional manipulation of the system, and it doesn't actually work most of the time. (That teaching comes from Talmud, Yoma 85b.)

We're called to have the best of intentions, and then to live up to them as best we can... knowing that we'll fall short of our own expectations sometimes, but not letting ourselves off the hook in advance. And -- no matter how good our intentions, we also have to keep the needs of others in mind, and not trample on others in pursuit of our own ends. One could argue that it doesn't matter how good my intentions are; if I stomp on your foot, it hurts you, whether or not I meant to cause pain. Intent matters -- but consequences matter too. The needs of others matter too. For me the first step is always intending not to hurt anyone; intending to do the right thing; intending to be kind and compassionate, to lead a life of mitzvot and connection, always. But I also need to be mindful that I may hurt someone else without intending to do so, and when that's pointed out to me, I need to apologize to the person I have hurt, even if I didn't intend to cause any harm.

September 1, 2013

#BlogElul 26: Hope

I live in hope. I always hope that a better world is possible; that we can change and grow; that we can make better decisions tomorrow than we made yesterday. I always hope that peace is possible, even in the most entrenched conflicts. I always hope for something better than what we know now.

In classical Jewish tradition there's a strong strain of messianic hope. Today different branches of Judaism speak in different terms -- the days of moshiach, the messianic age, that day to come when all of our broken places will be restored -- but although our framing language differs, our hope is the same. Hope for a world redeemed. Hope for healing. Hope for something better than what we know now.

I hope that humanity is on a trajectory toward wisdom and compassion and that we can each do our small part to help humanity along that path. In the words of the reverend Martin Luther King, z"l (quoting earlier minister Theodore Parker), "The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice." Or at least -- I believe that we can bend it toward justice. It's not an automatic trajectory; it's not as though, having started in this direction, we're inevitably going to reach the finish line.

(I'm also not always convinced that there is a finish line -- I think this may be more of an asymptotic curve, in which we we strive to move ever closer to redemption and wholeness, and what matters isn't whether we "get there" but how we choose to act along the way.)

But I hope that we can make choices in our individual lives -- and in the aggregate, through the leaders we choose and the policies we support -- to nudge humanity away from fear and a zero-sum mentality, and toward love and kindness and a consciousness of abundance in the world. There is plenty of everything we need in this world, if we can only learn how to share. It's human nature for those who have, to want to have more; and for those who don't have, to yearn to have. But there has to be a better way than what we've known in the world so far. And that's where hope comes in. Logic might argue that humanity will always behave as humanity has always behaved -- in ways which are generally self-centered. But I choose to hope for better.

I don't know that my hope actually makes a difference in the world at large. But it makes a difference to me. If I live in hope -- that those who are unkind will learn to be kind; that those who are unjust will learn to be just -- then I can face the world every morning with gratitude and welcoming. And that in turn enables me to do my own small part to make my hopes come true.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers