Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 180

August 31, 2013

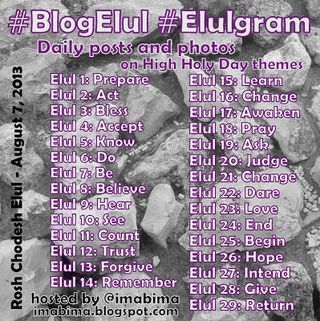

#BlogElul 25: Begin

I love that this is the time of year when my religious tradition tells me we are beginning again.

In the northern hemisphere where I live, we are at the height of harvest. Already the nights are cooler than they were, the days noticeably shorter than in high summer. The corn and tomatoes and peaches and lettuces are exquisite. Summer is waning. We know that winter is coming. And it is now -- as the evidence of our senses tells us that we are moving toward an end, dwindling down to nothing, the days getting shorter and shorter -- that our tradition says we begin again.

(In the southern hemisphere, perhaps some of the meaning of new beginnings in September is that winter is giving way to spring, to new green and new life. I've never spent a round of the seasons in the global South. I'd love to hear from someone who has thoughts on what this seasonal / spiritual transition is like from that end of the planet.)

This is the season when the school year begins. This doesn't have a big impact on my family yet -- our son's preschool runs right through the summer -- but I know that someday it will. And even though our son isn't beginning at a new school, he's starting in a new classroom soon, moving up a year. The goldenrod-yellow schoolbuses are beginning to ply the streets again. The stores are filled with notebooks and number two pencils, symbols of learning and of infinite possibility.

In Jewish tradition, it's always possible to begin again. This is in some ways the central message of teshuvah, repentance or return: that we can always start over. We can't undo the past, but we can move beyond it. Every morning, our liturgy proclaims, God returns our souls to us (having guarded them carefully while we slept) and every morning they are unblemished and pure. Every day we can make teshuvah, seek forgiveness, start over. Every day can be a new beginning.

August 30, 2013

#BlogElul 24: End

I'm rarely ready for things to end.

I'm rarely ready for things to end.I get attached to what is. Especially if it's something I'm enjoying (a weekend with dear friends, a stunning sunset over a lake, a cuddle with my child), though I'm capable of getting attached to even something I'm not enjoying (a dysfunctional relationship, a discomfort which becomes familiar), just because I get used to what is, and change is hard.

But everything ends. Both the sweet things -- sunsets, Shabbats, time with loved ones, every childhood, every life - and the bitter ones.

And every ending is also a beginning. The end of a particularly glorious Shabbat -- say, a Shabbat on retreat with my Jewish Renewal community, everyone all in white, a full day immersed in community and prayer and song and meaning! -- can bring tears, but without that ending, the new week can't begin. If we were to freeze time, we'd never move forward. This existence isn't meant to be static. Endings are built into the way things work.

I grieved my pre-child life once I became a mom. I missed the autonomy, both physical (what was it like before someone needed my body constantly for sustenance? soon I couldn't even remember) and emotional. I missed sleeping in. I missed spare time. I missed feeling in charge of my own life. But without the end of that life, I never could have experienced being someone's mother -- being this little boy's mother, in particular -- and those joys and sorrows (but mostly joys) have been so deep and so transformative that I now can't imagine who I would be if I'd never known them.

Some part of me doesn't feel ready for this Elul to end. I love this month of teshuvah and cheshbon ha-nefesh, taking an accounting of the soul. (And I'm never ready for August to end. I love the profusion of greenery, the fresh corn and tomatoes, the summer light.) But Elul has to end in order to get to the sweetness and the challenges of the Days of Awe; August has to end in order to get to the sweetness and the challenges of the coming autumn. Today has to end in order for us to reach tomorrow. Always.

One of the things I've always loved about the character of President Jed Bartlet on The West Wing is that he meets every ending with "...what's next?" I try to take that as a mantra, too. Everything ends. The question is: now that this is ending, what's next? Where do we go from here? What do we want the coming moment -- hour, day, week, month, year, lifetime -- to hold?

August 29, 2013

#BlogElul 23: Love

Connecting with God is all about love.

Connecting with God is all about love.I know that assertion seems strange to some of us, but I really believe that it's true.

Every morning we sing that God loves us with a great love -- ahavah rabbah ahavtanu. "You have loved us with a great love." Your love for us is so great that You give us Torah, a collection of stories and ideas and teachings to live by, as a parent lovingly gives their child stories and ideas and teachings to live by.

(I've been reading Heschel's Torah Min HaShamayim / Torah From Heaven recently, so I can't help being aware that I've just articulated the kind of view that Rabbi Ishmael would have espoused. Rabbi Akiva, in contrast, would argue that Torah is supernal and is inherently, mystically, holy -- the point isn't that it's rules to live by, the point is that it offers access to God. Well: either way, I suppose, Torah is an expression of divine love for us.)

Every night we sing that God loves us with an unending love, a forever love, a love which spans worlds. Ahavat olam beit Yisrael amcha ahavta -- "You have loved the house of Israel with an ahavat olam, an unending love!" Or, in the words of Rabbi Rami Shapiro's beautiful poem, set to music so lovingly by Shir Yaakov, We are loved by unending love. (I love that setting and that melody. We'll use it at our evening services during the Days of Awe this year at my shul.)

God's love for us is unending and infinite. I believe that the whole of creation, from the most microcosmic particles to the vastest galaxies, is an expression of divine love. God so overflows with divine love that God brings creation into being in order to have somewhere to direct that love, in order to have conscious beings with whom God can be in loving relationship.

And the Days of Awe are all about love. Even the parts which seem, on the surface, to be about justice and repentance. Because God loves us, we are always already forgiven...but that doesn't obviate our need to do the work of teshuvah, to repair what's been broken in our selves and our relationships and our world.

A few weeks ago when the Wednesday morning coffee shop clergy met (to read some of the aforementioned Heschel) we wound up in a conversation about our liturgy and whether/why it matters. One of my colleagues offered the metaphor that all of our fine liturgies, our prayers, our melodies, all of the high pomp and circumstance of these most elevated services of the year...are like a finger-painting a child proudly brings home to the parent. And because that parent loves their kid, they say "How beautiful, sweetie! I love it! I'll hang it on the fridge!"

A few weeks ago when the Wednesday morning coffee shop clergy met (to read some of the aforementioned Heschel) we wound up in a conversation about our liturgy and whether/why it matters. One of my colleagues offered the metaphor that all of our fine liturgies, our prayers, our melodies, all of the high pomp and circumstance of these most elevated services of the year...are like a finger-painting a child proudly brings home to the parent. And because that parent loves their kid, they say "How beautiful, sweetie! I love it! I'll hang it on the fridge!"

No loving parent would ever say "Wow, that's a terrible drawing; what kind of artist do you think you are? You should be embarrassed to even bring that into my house." We try so hard to have grand high holiday services, to follow all of the rules and the customs of our communities, to make these services as perfect as possible. And sure, our efforts matter. But God isn't up there somewhere muttering to Himself, "what terrible artists. They should be embarrassed to even bring that into My house." God is the loving parent Who says, "How beautiful, sweetie -- you made Me a service! I love it! I'll treasure it."

Because God knows we're doing the best we can do. With our services -- with our spiritual lives -- with our lives writ large. And God loves us even though we make mistakes all the time, and even though our art isn't so great. We are loved by unending love. Even if we haven't set foot inside a synagogue since last Yom Kippur, even if we've been steadfastly ignoring God and forgetting to check in every day and every week and every month, even if we've screwed up royally. We are loved. And because we are loved, we have the strength to love in return.

August 28, 2013

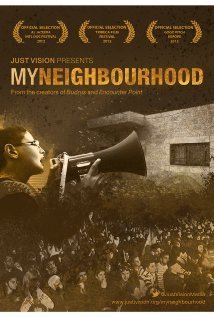

My Neighbourhood in my neighborhood

Earlier this week I attended a screening of the short (25 minute) documentary film My Neighbourhood at The Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield. The filmmakers describe the film as being about "a remarkable nonviolent struggle in the heart of the world's most contested city." Here's the movie's official trailer:

I'd read a lot about it (see East Jerusalem Doc 'My Neighbourhood' Wins Peabody Award by Emily L. Hauser in The Daily Beast, or Sumeet Grover's review in the Huffington Post.) In addition to winning a Peabody, this short film won both at the Warsaw Jewish Film Festival and the Al Jazeera Documentary Festival -- how many movies can make that claim?

I knew I wanted to see it on the big screen. And I was especially interested in seeing it accompanied by the panel discussion which followed -- featuring Rebecca Vilkomerson, the executive director of Jewish Voice for Peace; Israeli writer, activist, refusenik, and poet Moriel Rothman (a frequent contributor to The Times of Israel and to Ha'aretz); and moderator Victor Navasky, Publisher emeritus of The Nation magazine and professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

I expected that the film and subsequent discussion would move, challenge, and discomfit me. I find that trying to look at the Middle East with clear eyes and an open heart always does.

Let me just say this: You should watch the film. It's 25 minutes long, and the whole thing is available on YouTube. It tells its story better than I can. If this is a part of the world that you care about; if peace and justice are issues that you care about; you should take 25 minutes of your life and watch this film.

Watching it made me weep.

After the film, Moriel told the story of protesting in Sheikh Jarrah for the first time, and of what it was like for him to hear police shouting that he was breaking the law -- and how it took him a few minutes to realize they were talking to him. He described himself as an observant Jew and Israeli citizen who has always loved Israel and thought of it as the place where he always wanted to be.

After the film, Moriel told the story of protesting in Sheikh Jarrah for the first time, and of what it was like for him to hear police shouting that he was breaking the law -- and how it took him a few minutes to realize they were talking to him. He described himself as an observant Jew and Israeli citizen who has always loved Israel and thought of it as the place where he always wanted to be.

He cited the original March on Washington (the anniversary of which is this week), and he spoke about the (US/American) Voting Rights Act and how once that act was in place, "the law was on the side of justice," though certain individuals in government (for instance, noted segregationalist Governor George Wallace) weren't acting justly yet. "The situation in Jerusalem is different," he stressed, saying:

"The law is the problem. Israeli law allows injustice. There are different sets of laws for different people. If you are a Palestinian living in Jerusalem you are subejct to different laws than if you are an Israeli living in Jerusalem."

Moriel explained that after 1948, some 700,000 Palestinians became refugees, and the Israeli government gave their properties, by and large, to Jewish refugees from Europe. In 1950, Israel enacted something called the Absentees' Property law (hold that thought, Moriel said; he would return to that law momentarily.) "In 1967, Israel conquered territories including the West Bank, the Golan, Sinai, Gaza and what is now called East Jerusalem. East Jerusalem was of course a concept which didn't exist until '67," Moriel pointed out. "Until then it was 28 Palestinian-Arab villages...this is different from the West Bank where according to Israeli law the land is still disputed."

In Israeli law, East Jerusalem has a different status than the West Bank. (I wrote about this in my 2008 post A Day with ICAHD -- which I still think is worth reading, though it's five years out of date.) The West Bank is "disputed" or "occupied" territory, whereas East Jerusalem was annexed; according to Israeli law, it is part of Jerusalem. And Israeli law -- specifically, that Absentees' Property law -- says that Jews with property claims in East Jerusalem from before '48 can take these claims to court and reclaim their property.

Usually the courts rule in favor of the Jews with the property claims (see Israeli policy pivot strengthens grasp on East Jerusalem, Christian Science Monitor, June 2013), though this doesn't necessarily mean that the houses return to their previous owners. Frequently, Moriel explained, the properties are purchased by the Israel Land Fund (an organization which works toward its vision of "Greater Israel"), and the ILF gives the properties to young yeshiva buchers who want to be part of the struggle to rid East Jerusalem of Arabs. (We heard from some of those voices in the film.) Of course, Absentees Property law cases have to be decided in court, and they do receive due scrutiny. But, Moriel noted:

"The court never asks the question of what it means for a country to call itself a democracy and have two different sets of laws for different people. Palestinians who lost their homes in '48 not only can't take their claims to court, but they are often forbidden from entering Israel at all. This is the injustice taking place in Sheikh Jarrah -- and in Silwan and in other places, as well."

"It's crucial," he added, "that we recognize and remember that East Jerusalem is just as occupied as the West Bank.... [When we talk about] the peace process, we're talking about bringing two parties to the table -- meanwhile there are families in Sheikh Jarrah facing eviction, and when they are evicted, they have no recourse. When we talk about making peace, we need to remember that any discussion of peace process is hollow and meaningless if it doesn't take into account peace on the ground."

Moriel reminded us, "The Torah teaches: you should have one law for the citizen and for the stranger."

Then we moved into Rebecca Vilkomerson's remarks:

"As someone steeped in this issue, watching the opening of this film, it reminds me why I do this work -- the level of injustice that it documents is breathtaking.

If you have an open enough heart, this issue is so easy to understand. But the way that we move toward peace is often fraught with difficult conversations."

She began by speaking to us about her own journey. "Many of us in the Jewish American community have had to overcome some strong conditioning in order to even hear these stories wholly." She told a funny story about meeting her Israeli husband-to-be, being introduced by the Palestinian owner of a coffee shop they both frequented in San Francisco. And she said:

"I knew I believed in equality of citizenship regardless of race, ethnicity, religion; I knew I believed in the universality of human rights; and the more I learned, the more I realized -- much to my sadness -- that Israel was not living up to those values."

She told about picking olives with Rabbis for Human Rights (an experience probably quite like the one chronicled here), about driving Palestinian children who had permits to receive care at Israeli hospitals to those hospitals, about working with Bustan (an Israeli NGO which works with Bedouin and Jewish communities in the Negev), etc -- and also about working with groups which worked in solidarity with Palestinian villages, accompanying Palestinians to protests and so forth. "I swallowed my share of tear gas at the hands of the (Israeli) military." She told stories about going home to wash the tear gas off of her skin and clothes before picking her children up from gan / kindergarten. "That's the joy and challenge of life in Tel Aviv."

"As a Jewish person who hates how Israel acts in my name...I have a personal investment in Israel's future; my girls have Israeli citizenship, I want Israel to be a place where I would be proud for them to live!"

She also pushed us to consider why we're listening to a panel of two Jews moderated by an American Christian, rather than listening to the voice of someone from the Palestinian community. "Why is the Jewish voice on Israel and Palestine so often considered more legitimate than hearing the voices of Palestinians...when [Palestinians] are undoubtedly the ones most affected by what's happening there?"

"Part of the work we need to do, we who are Jewish," she suggested, "is help break down the walls of prejudice which make Jewish voices privileged in these conversations. Even if that means giving up some of our own power to drive -- some would say 'to police' -- these conversations."

"Part of the work we need to do, we who are Jewish," she suggested, "is help break down the walls of prejudice which make Jewish voices privileged in these conversations. Even if that means giving up some of our own power to drive -- some would say 'to police' -- these conversations."

The most critical way that we in the United States can support this struggle, she said, is by supporting the Palestinian-driven nonviolent movement of boycott, divestment, and sanctions -- known colloquially as "BDS." At that moment a buzz went around the room, because everyone in the audience knew what a hot-button phrase that has become.

The peace process, Rebecca noted, has gone on for 20 years and has done nothing but entrench the settlements. (Indeed: more settlements have been announced even since this most recent round of peace talks began.) She continued:

"Israelis have all the time in the world to talk about

peace: they can go to school, work, receive health care, travel freely.

Meanwhile, Palestinians are penned into ever-smaller

areas of land, their freedom curtailed by army, settlers, police. This inequity is the difference between being the occupier and the occupied -- it's the furthest thing from the level playing field necessary for honest negotiations."

Rebecca offered some history around settlements, noting that Prime Minister Shamir saw the settlements as a strategic bulwark against a Palestinian state. She pointed out that this hasn't just been a Likud stance; Yitzchak Rabin, whom many of us revere for working for peace, also supported settlements. She offered a quote from Rabin (also cited in an October 1990 issue of Davar): "For all its faults, Labor has done more for expanding Jewish settlements than Likud with all of its doing. It is we who built the suburbs" -- that's what they call them, she added; suburbs, not settlements -- "in the annexed part of Jerusalem." Israel talks about peace, she told us, but its actions work against peace every day.

Here in the States, she noted, between the presence of AIPAC, and the weapons companies which benefit from US arrangements with Israel, and certain politically powerful branches of evangelical Christianity (which believe that ingathering the world's Jews in the Holy Land is a necessary step toward Armageddon), conversation on these issues has been strangled. The accusation of antisemitism is used to silence critics of Israel or of US policy.

But surely our responsibility as citizens, Rebecca argued, is to be aware of state power and not to trust it blindly. (The Snowden story currently unfolding ought to teach us that.) Given these conditions -- which she described as an ever-worsening human rights situation on the ground, compounded by the US's inability to create a situation of negotiations between equals -- "the peace process," she suggested, "dooms us to something worse than failure: a false hope which perpetuates an unjust situation on the ground."

BDS, Rebecca said, is a movement which allows people all over the world to peacefully act on their values. Palestinians (she told us) have entered into BDS because they recognize that the violence of the second intifada led them nowhere -- and yet, she noted, the American Jewish establishment responds to BDS with the same vitriol with which they responded to that violence, which is problematic.

Boycotts, divestments, and sanctions, she noted, have been employed in a variety of struggles throughout history: boycotts of sugar and rum in protest of the slave trade in the 1700s, in Gandhi's boycott of British goods, the Montgomery Bus Boycott in this country, the use of boycotts and economic sanctions in helping to end South African apartheid. "Israel's situation is not exactly like any of these, but it is similar enough that it's reasonable to think that BDS can work." She added:

"BDS is an economic and cultural tool to impose consequences on Israel where there had been none. These consequences can create emotional reactions for those of us with ties to Israel. But just as previous boycotts did not intend to destroy their targets but sought to make them better places, so now with BDS directed toward Israel."

She explained that JVP participates in BDS efforts which target the occupation specifically. This is what's known as targeted BDS. (I've written about this before; I find the distinction meaningful, though much of the current American Jewish conversation ignores it.)

Rebecca concluded her prepared remarks by urging us:

"Think about the steps that you can take to be part of this growing movement for a just peace in Palestine and Israel. Like the March on Washington, I believe that this is one of the most critical fights for justice in our time."

Then we moved into Q-and-A. Victor Navasky asked: are we better off or worse off without a peace process of some sort? Rebecca said: "This is counterintuitive but we might be better off without one. It gives a false sense of progress, and meanwhile the situation on the ground grows more unjust and less changeable by the day."

Moriel added:

"I think the peace process can be extremely dangerous; it can take the attention of people who are committed to peace, and turn them into people who are committed to process. At best the peace process should be treated with skeptical neutrality. We need to pay attention to issues that actually matter, happening day by day. Many in power want us to ignore what's actually happening day by day."

Someone asked: if Israel gives Palestinians the right to vote, will Israel still be a Jewish state? Moriel replied, "I am a proud Israeli citizen and a proud observant Jew, and I don't want Israel to be a Jewish state -- I want it to be an Israeli state. I want to see a Palestinian state alongside an Israeli state. In the Israeli state Hebrew would be the national language, and there would be an expression of Jewish communal values in the land of Zion... Israel should be an Israeli state in which each citizen, whether Palestinian or Jewish, has an equal stake."

Rebecca added, "I want to reframe the question and ask: what is a Jewish state? 20 percent of the population there now is not treated equally; is that what we want a Jewish state to be? There are Jewish women being kicked off of buses because Israeli men want their seats; is that what we want a Jewish state to be? ...As an American I support separation of church and state. In America we don't want laws to treat us unfairly as Jews, as a religious minority here. To say that those are my values here but not there...?"

She stressed that this is not an official JVP position --" we don't have a position on one state or two states" -- but, she suggested, "what I can imagine is a confederation -- with a Palestinian autonomous area and an Israeli autonomous area, so that people can live in the communities they want -- with a shared economic framework."

Someone else asked: define what you would suggest that people boycott? Rebecca said, "JVP's position is that we participate in boycott and divestment efforts, mostly divestment, which target the occupation specifically. Granted, sometimes to draw a line between occupation and the instutitions of the state can be difficult -- but we boycott products produced in occupied territories and companies which profit from the occupation, not Israeli products."

Another question after that raised the issue of "normalization," which is a big and complicated issue. There was also an interesting conversation about the pros and cons of economic sanction vs. cultural boycott, and about the current state of Israeli politics. I didn't manage to take notes on all of it; what you've read here is most of what I wrote down.

I'm still reflecting on this event. The film moved me and made me angry and sad -- it impacted me most in the realms of yetzirah (heart) and atzilut (spirit). The panel discussion was enlightening and interesting primarily in the world of briyah (intellect.) I guess the only thing missing was assiyah, action and physicality, since we're on the far side of the planet from where this conflict continues to unfold.

I'm still reflecting on this event. The film moved me and made me angry and sad -- it impacted me most in the realms of yetzirah (heart) and atzilut (spirit). The panel discussion was enlightening and interesting primarily in the world of briyah (intellect.) I guess the only thing missing was assiyah, action and physicality, since we're on the far side of the planet from where this conflict continues to unfold.

I have long experienced a powerful cognitive dissonance between the Israel of my dreams, and the Israel of lived realities. Between the Israel in which I was taught to believe and hope, and the Israel whose government takes actions and makes choices which I believe run counter to the prophetic vision of justice cherished in Jewish tradition.

I have friends and loved ones who proclaim Israel's shining glories, and friends and loved ones who bemoan her moral failings, and both are right -- though I've found that attempting to translate between those two worldviews can leave me feeling torn apart. (It's hard to live in a place of you don't have be wrong for me to be right.) And I always want to be conscious that the struggle of American Jews like me to reconcile Israel's beauties with Israel's misdeeds is not remotely important. What matters most is the real people who live in Israel and Palestine, created in God's image, whose lives are damaged by this conflict every day.

Palestinians

and Israeli Jews have come together in a vibrant non-violent movement

to protest the eviction of dozens of Palestinian residents from and

influx of ideological settlers into the East Jerusalem neighborhood of

Sheikh Jarrah. - See more at:

http://www.truah.org/issuescampaigns/...

Jerusalem is a beautiful and holy place. and

Because American Jewish discourse around this is so polarized and polarizing, all too often I am silent. I rationalize my choice: I remain silent because I don't want to be the American outsider whose voice is amplified at the expense of those who actually live there; because I am busy with other things; because there are so many different fronts on which I want to help create change, and this one is both far-away and out of my control. But seeing My Neighbourhood reminds me that silence is complicity with the status quo, and that this status quo is not something I want to tacitly support.

Rabbi Alana Suskin recently wrote that depriving other people of their basic rights and dignity is a "defiling of the land" as surely as anything which Jeremiah decried. Seeing this film heightened my sense that she is right.

The film and panel discussion were part of the fourth annual

Donald and Doris Shaffer Memorial Lecture Series in the Berkshires.

Donald Shaffer passed away in February -- see Don Shaffer: In Memoriam -- and this year's series honors his legacy. My gratitude is due to the lecture series organizers for bringing such a thought-provoking event to Pittsfield.

Related reading:

My colleagues at T'ruah: the rabbinic call for human rights ( Rabbis for Human Rights North America) have a powerful collection of resources on Jerusalem, including:

The Complexity of Jerusalem ("Jerusalem is a beautiful and holy place. // It is also a complicated and painful place")

and Inside East Jerusalem Neighborhoods

("Palestinians and Israeli Jews have come together in a vibrant

non-violent movement to protest the eviction of dozens of Palestinian

residents from and influx of ideological settlers into the East

Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah...")

Also don't miss their resources on the film (including a terrific supplemental discussion guide)

Also worth reading:

The Unsettling Question of Israeli Settlements by Matthew Duss at The American Prospect

Is Normalization Possible before Israel Ends the Occupation? by Daoud Kuttab

Facing Eviction in Sheikh Jarrah: One of Israel's Most Contested Neighborhoods, Sarah Wildman, The New Yorker

#BlogElul 22: Dare

"As we bless the source of life, so we are blessed

As we bless the source of life, so we are blessed

and the blessings give us strength, and make our visions clear

And the blessings give us peace, and the courage to dare

As we bless the source of life, so we are blessed."

That's Faith Rogow's poem. In Jewish Renewal contexts, we sing it fairly often as a prelude to the Bar'chu, the call to prayer.

I'm always struck by the line about the "courage to dare." A quick Google search reveals that the phrase means different things to different people -- e.g. the Courage to Dare Foundation, bringing breast cancer awareness to rural communities -- but for me the phrase always evokes this Faith Rogow poem. I love the experience of invoking the courage to dare as part of our lead-in to the Bar'chu.

There is something daring about entering into prayer. About standing before God and offering our praises and our supplications as though we actually believed that the Creator of Heaven and Earth, the Source of All Being, were listening to us. More: as though the Source of All Being actually cared what we had to say. That's the audacious claim made by Jewish prayer practice every day: that we can dare to stand before God, expecting God to listen.

During Elul, we dare to imagine that our process of self-examination is more than mere navel-gazing. That our inner work of teshuvah matters to how we will be in the world in the coming year; that, like our prayers, it matters to God.

During Elul, we dare to hope that despite all of our patterns and ruts and familiar old grooves, we can strive to be better people than we have been. We can aim to be more conscious, more kind, more giving, more forgiving in the year to come.

During Elul, we dare to face all of who we are: the places where we are glorious, and the places where we are dreadful. Our best actions of the year now ending, and our worst ones. We dare to admit that all of this is part of who we are.

We dare to stand before God as we take an accounting of ourselves. We dare to claim that we can change. We dare, even, to ask God's help in being the change we want to see in the world.

August 27, 2013

#BlogElul 21: Change (2)

Sometimes, when I'm leading Shabbat morning services, I pause during P'sukei D'zimrah, the series of poems and psalms which come after the morning blessings but before the formal service begins with the Bar'chu, and I say a word about all of these praises which we offer.

Many of my students over the years have asked me: why do we say all of these words of praise? Song, praise, adulation, thanks, glory, splendor -- this part of the service is positively dripping with praise. What gives? Is God so insecure that S/He needs to hear this kind of thing every day?

In my understanding, we offer these praises not because God needs to hear them but because we need to say them. Because when we place ourselves in a posture of gratitude and awe, day in and day out, something in us changes. When we recognize that we're not the center of the universe, something in us changes.

Sometimes I think that the point of prayer -- the point of all of our spiritual practices -- is to help us refine ourselves, to help us change, into the people we're meant to be.

Children benefit from routine. I am the parent of a going-on-four-year-old, and I can tell you from experience that daily routines help a lot. Just as our kid is happier and healthier when he gets meals at regular times, nap (or quiet time) at a regular time, bed at a regular time -- so I am happier and healthier when I say prayers with regularity. When I stop every day to articulate gratitude and praise to God.

Having a regular prayer practice changes me. Lighting Shabbat candles every week changes me.

And sometimes I'm resistant to change. I like the way I am now! I don't want anything to be different! I don't want to give anything up -- like maybe my autonomy or my sense of self or my self-satisfaction in the way things are!

When I catch myself writing those scripts, I try to just...notice. With compassion, without judgement. Hey, lookit that, I'm doing that thing again. Where I'm resistant to change because change is scary, growth is scary, and I'm not always ready for what's next. The critical thing at that point, for me, is to just take a deep breath and let the tension flow away. It's okay if I'm not ready to change right this instant. Take another breath. Maybe then I'll be ready. Or maybe the breath after that.

Sometimes change foists itself on us, ready or not. Major health crises can do that. So can parenthood. Getting, or losing, a job can precipitate change. All kinds of things can. But I think if we've already accustomed ourselves to the constancy of change, then when changes come along they're not so terrifying. Just as when we've already accustomed ourselves to recognizing that there's something in the universe greater than ourselves, sudden moments of awareness which bring that recognition to the fore aren't so overwhelming.

Change is always coming. The best tools I know for dealing with change are the best tools I know for dealing with life. Compassion, kindness, plenty of sleep, good hot showers, hugs, prayer. Patience with yourself when you screw it up. Willingness to try again. And again. And again.

You may have noticed that "change" appears twice in this year's set of #BlogElul prompts. Hence the (2) in this post's title. Fortunately change is something I think I could riff on every day, since my sense of change is always -- well -- changing.

August 26, 2013

#BlogElul 20: Judge | On why God-as-judge challenges me, and why I still need the metaphor

One of the predominant images in our High Holiday liturgy is God-as-judge.

One of the most challenging images (for me) in our High Holiday liturgy is God-as-judge.

It's so easy to think of the human judges who have not ruled justly, and to project our anxiety about unjust human rule onto God. To respond with reactivity: I don't want to be judged. To buy into that ugly old line which says that Judaism is a religion of stern and strict Law (while Christianity, the unjust saying goes, is the corrective, a religion of Love.) Ugh. No offense intended to my Christian friends and loved ones; that's just such an appalling (and incorrect) oversimplification.

What fascinates me this year is this: even though I know better than to swallow any of that old negativity, it still crops up in my consciousness. I still struggle sometimes with the metaphor of God as judge.

But it is a metaphor. As surely as any of our terms for God are metaphor. God isn't really a Father or a King or a Judge, a Mother or a Beloved or a Wellspring. And at the same time God is all of those things and more. God is the limitless ein-sof of the kabbalists' imagining, that infinity without-end which human minds can't possibly grasp. And God is every one of the qualities we find in the sefirot as they flow and chain and spiral into creation; God is boundless love and boundaried strength and the balance between the two, God is endurance and humble splendor and generativity, God is immanent in all creation. God is masculine and God is feminine and God is neither and God is both. And God is Friend...and God is Judge.

God-as-judge can be a powerful metaphor -- but we have to remember that it's only a metaphor, and that it isn't the only metaphor. If God is a judge, S/He is the Judge Who rules with the perfect balance of strength and compassion, discernment and mercy.

When we hear that a person has died, the traditional response is Baruch dayan ha-emet, usually rendered as "blessed is the True Judge" or "blessed is the Judge of Truth." Rabbi Marcia Prager taught me that since the word emet, truth, contains the first, middle, and last letters of the alef-bet (א, מ, ת), we can creatively read Baruch dayan ha-emet as "Blessed is the judge of beginnings, middles, and endings." Perhaps that's one sense in which God is our Judge: God is present, with clarity and discernment, as our lives begin and unfold and end.

And God is that moral force which calls us to be our best selves, which pushes us to recognize when we are falling down on that job, which goads us to notice how we could be better in the year to come. At least once a year we all come before the One and have to make a cheshbon ha-nefesh, an accounting of our souls. As much as I love the personal metaphors for God -- Mother, Beloved, Parent, Source -- I recognize that there's a certain kind of awe-some trembling in which I don't necessarily engage when it comes to those more intimate metaphors. At this season, I need God to be a Judge so that I can meet that aspect of God Which helps me to judge myself.

Judge is a partzuf, a face or form or visage or mask through which we can relate to the Infinite. It's not the only mask God wears, but it is one of the ones we most often call upon in our High Holiday liturgy. What role does this partzuf serve for us? What is it that we need to call forth in ourselves which we can only call forth when we find ourselves face-to-face with this aspect of God?

August 25, 2013

Practices from Ki Tavo for entering a new phase of life

This is the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Ki Tavo, last week's Torah portion. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

When you enter into the land, Torah tells us, be conscious of where you are and what you're doing. Bring the fruits of your labors as a gift to God. And then say, out loud, a passage which many of us may recognize from the Pesach haggadah, one which begins "My father was a wandering Aramean..."

What a fascinating instruction this is to find at the beginning of parashat Ki Tavo.

The most obvious reading of this passage is that it describes practices the ancient Israelites followed when entering into the Promised Land and making sacrifices there to God. Yes: that's one way of reading it. Absolutely.

But I'd like to suggest a second reading. This text can also offer us instructions for how to act, what to do and say, when we cross a boundary in our own lives from one phase to another.

What happens if we read this as a text about crossing the spiritual boundary between one part of our lives and the next?

When you enter into this new part of your life, and possess it and settle in it -- when you stop looking back to the past or anticipating the future, when you make the conscious choice to be in this moment, when you enter wholly into the here and now.

You shall take some of the first fruit of the soil which you harvest -- take your hard work, your spiritual gleanings, the new insights and creativity which you have tended and raised up like seedlings from the ground.

And go to the place where Adonai your God will choose to establish the divine Name -- bring your presence in this moment, and your spiritual gleanings, into connection with something beyond yourself.

Go to the priest in charge and say to him, "I acknowledge this day before God that I have entered the land" -- go to someone you admire and trust, someone who facilitates your sense of connection with God and tradition, and affirm aloud for that person that you are here, in this moment, without regrets or anticipation.

You shall then recite "My father was a wandering Aramean" -- speak, aloud, the truth of where you come from and how you got here. Remember your ancestors, both genealogical and spiritual, and what they went through. Remember being in a place of constriction and misery. Remember what it feels like to trust that God will lift you out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Connect the bounty you are experiencing now with that same God Who brings you out of the house of bondage and into covenant and freedom.

Then you shall enjoy, together with the family of the Levite and the stranger in your midst, all the bounty that Adonai has bestowed upon you and your house -- only then, once you have made yourself present in this moment, and harvested your insights and wisdom, and placed yourself in relationship with someone who helps you connect with God, and thanked God for the new stage of your life which you are beginning in this moment, and remembered where you came from, and thanked God for the blessings in your life -- then you will have the abundance and expansiveness to celebrate along with the stranger in your midst, the outsider who is perennially marginalized but whom you welcome into your celebration.

What would it feel like for us to do what Ki Tavo commands? We can't experience the entry into the Promised Land as Torah tells us our ancestors did -- but we can experience this entry into the promised land of the heart and the spirit in every moment if only we are willing to do the work and open ourselves up.

And what better time to do this work than during Elul, as we make ourselves present and remember where we come from and thank God for our blessings in preparation for the Days of Awe?

#BlogElul 19: Ask | on Psalm 27, and what that psalm teaches me to ask

One thing I ask, I ask of You, I earnestly pray for...

It's traditional to read psalm 27 every day during the month of Elul. I don't always manage to daven the full psalm in Hebrew, but I try to include the psalm in every day of this month somehow.

Over the years, I've collected several different variations on the psalm -- some creative interpretations, some melodies, some poems:

Reb Zalman's translation of psalm 27

Nava Tehila melody for psalm 27, verse 8

Achat Sha'alti melody by I. Katz

R' Brant Rosen's psalm 27 - you are my light and my hope

Kirtan Rabbi's Achat Sha'alti (info) and mp3

I love these poems and adaptations and melodies. But I don't want to lose sight of the point of the practice of engaging with this psalm daily during Elul. It's not (just) about the poems and the songs we've created to bring the psalm to life. It's about the yearning which is at the psalm's heart.

What is it that I ask of God at this time of year?

The psalm leads me to ask: please let me be with You. Let me dwell in Your house -- or, maybe, let Your house be manifest in this body, and in this place, in which I dwell. When I sit meditation, let the place around me become Your place. Let me be connected with you all the days of my life -- some of our sages say, "the days of my life" would mean in the daytime, but "all the days of my life" means days and nights both; 24/7; all the time. Let me experience Your wonders. Let me be so aware, so conscious, that every moment telescopes into intimate connection with Your presence.

The psalm leads me to ask: don't hide Your face from me. I know that in my experience You are sometimes present, sometimes not -- and I know that You are always with me, even at the times when I can't perceive Your presence. But please, Holy One of Blessing, don't hide from me. Don't turn away. All of life is impermanent; even my parents, whom I love more than I can say, will someday be gone. You, God, are the One Who is always here, will always be here, forever and ever, world without end. I am like a child crying in a darkened bedroom, frightened of the thunder. Help me to remember that You are with me, even when I feel alone.

The psalm leads me to ask: teach me Your way. Give me the wisdom to yearn for Your path, and the strength to pursue it even when that isn't easy. Help me to access the discernment and the kindness and the patience and the gratitude which are the natural outgrowth of following Your way. Teach me how to be the person I most yearn to be. Help me to be better than I have been. I know that the world is full of distractions and that I am prone to reactivity just like anyone else, but I want to learn how to be the kind, generous, mindful person You have given me the capability to be.

So maybe "one thing I ask of You" is a bit of an understatement. Or maybe all of these other things flow from that one first request: that I might dwell in Your house, knowing Your beauty and experiencing Your wonder, being with You in Your holy place.

There are other things I ask for every day, many of which are in the daily amidah. Give me knowledge, give me the ability to make teshuvah, please heal those who are sick. Forgive me. Bless the elders of my community. Bless the cycle of this year, help my nation to reach justice, help those who do cruel and hateful things to change their ways. Hear our prayer. Bring us peace.

It's a lot to ask. And sometimes I struggle because I know that not everything we ask for is going to be granted. But I think we need to keep asking. In asking God for what we want and need, we articulate those needs and yearnings not only to God but to ourselves.

August 23, 2013

A reprint of an old Elul poem

Waiting

August: my mind changes.

I want to think swimming,

grapefruit sorbet dripping

down a sugar cone, berries

behind the house, but I can't.

I'm cleaning, humming

the song my father loves

the way Barbra sings it,

looking for my bobby pins,

checking my tallis case.

One year mice chewed through.

At my sister's shul in Boston

another woman had my bag,

ivory on ivory, embroidered.

I had to claim the holey one.

Summer's not over, not even

here where snow falls

two months too soon.

Every night it cools I think

of apples weighting trees.

Zucchini bread like practice

for honeycake, the same

baking pan, the same motions.

The horn of the year spirals

to its tekiah g'dolah.

My friend Marisa James posted this poem to Facebook recently, saying that she was finding it meaningful this month. I hadn't reread it in a long time; I'm gratified to see that I still like it!

This poem was first published in my second chapbook, What Stays (Bennington Writing Seminars Alumni Chapbook Series, 2002.) Apparently that chapbook is available online, though I can't vouch for the seller; I also have some copies available for sale for $8, and if you want one, drop me a line and we'll work out shipping costs.

The song referenced in the poem is Max Janowski's setting of Avinu Malkeinu.

After this poem was published, I started writing and sharing Elul poems each year during the lead-in to the Days of Awe. You can read my archived Elul / New Year's poems here: VR New Year's Poems 2003-present.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers