Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 181

August 23, 2013

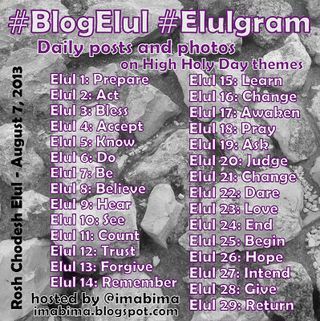

#BlogElul 17: Awaken

My friend and teacher Rabbi Hanna Tiferet Siegel has an album called Awaken, Arise!. The title track begins, "Awaken, arise to the wholeness of your being / Awaken, arise to the beauty of your soul..."

My friend and teacher Rabbi Hanna Tiferet Siegel has an album called Awaken, Arise!. The title track begins, "Awaken, arise to the wholeness of your being / Awaken, arise to the beauty of your soul..."

This is one of the side effects of regular prayer practice, for me. When I dip into davenen I awaken, in Reb Hanna's words, to the wholeness of my being. I remember that there is more to me than whatever's at the top of my to-do list this morning.

Elul is a season of awakening and arising. The great medieval sage Maimonides (also known as Rambam) heard in the shofar's call the words "Wake up, you sleepers from your sleep, you slumberers from your slumber. Search your deeds and return to Me in teshuvah!"

It's traditional to hear the shofar every day during Elul. For some of us that means blowing shofar each day. For others, maybe hearing the shofar on YouTube. And for still others of us, the hearing of the shofar may be more metaphorical than actual.

But even a metaphorical shofar can pack quite a punch. Wake up! The year is waning! Are you the person you intended to be?

These days I most often awaken to our son's presence in our doorway. Each day he comes to wake me into relationship, into my role as mother and caregiver. His footfalls on the stairs call me out of sleep. Wake up! It's morning-time! I had a good sleep! Can you put on your robe and make me waffles? His needs are generally pretty prosaic, but they're non-negotiable. When he's hungry, he's hungry -- it doesn't matter if I wanted to sleep another ten minutes.

The presence of our not-quite-four-year-old is a kind of shofar, waking me to the responsibilities of my day.

Everyone I meet can be a kind of shofar. Every voice can call me to awareness and recognition: of wholeness and brokenness, of "the beauty of my soul" (in Rabbi Hanna Tiferet's phrasing), of the ethical realm in which I have obligations to the Other, of the ways in which I've missed the mark and need to do better.

Suddenly you are awakened by a strange noise, a noise that fills the full field of your consciousness and then splits into several jagged strands, shattering that field, shaking you awake. The ram's horn, the shofar, the same instrument that will sound one hundred times on Rosh Hashanah, the same sound that filled the world when the Torah was spoken into being on Mount Sinai, is being blown to call you to wakefulness. You awake to confusion. Where are you? Who are you?

That's Rabbi Alan Lew in his book This Is Real And You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation, the chapter on Elul, which is titled "The Horn Blew And I Began To Wake Up." This is the month during which we are called to wake up to all of who we are, to all of who we have been, to all of who we could become.

August 22, 2013

#BlogElul 16: Change

"To everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven..."

Many of us sing that song (in its setting by The Byrds) during Sukkot, the festival of harvest and impermanence, which begins four days after Yom Kippur. The megillah (scroll) assigned to that festival is Kohelet, after all -- known in English as Ecclesiastes -- which is the source of that bit of scripture.

We may study Kohelet during Sukkot in particular, but impermanence is a reality all year long. Change is a constant. Even when things appear to be standing still, subtle change is always unfolding.

I'm particularly conscious of this at this time of year, when the glorious greenery of the Berkshire hills begins to shift. Early in August, the first yellow or red maple leaf blows across my line of sight. I always feel a pang. I love the long days of summertime, the golden light, the abundance of flowers and leaves and vegetables and fruits. I'm not ready!

But I know that part of what makes the Berkshire summers so glorious is that they don't last forever. (In the words of House Stark, for any Game of Thrones among you: Winter is coming.) We don't live in the tropics; the days here shift, longer to shorter, warm to cold, and then back again. The real beauty is in the rhythm of the constant change.

Seasons are cyclical; human life is linear, more or less. (Though my good friend Reb Jeff wrote a beautiful post recently about how human life isn't really as linear as we tend to think -- Contrast and Commonality -- which I highly recommend.) There are cycles and circles and recurring themes in every human life, but outside of science fiction we experience the arrow of time going in one direction. We're all growing older, every day; moving further away from the transition into this life, and toward the transition out of this life. But as with the seasons, part of the work of this life is learning to find the beauty in the change, instead of getting too attached to any stage along the way.

I love having a not-quite-four-year-old. This is a charming, fun, funny, exuberant, wonderful age. There are moments when I think: I wish I could hit a cosmic "pause" button and stay with this age, because I love the person our son is right now! I love the cuddles and the silly songs and the goofiness and the earnest sweetness. But then I remember: if I could somehow pause him at this age, I wouldn't get to experience the blessings (and challenges, and frustrations) of what comes next. And what comes after that.

In parenting, it often seems that the only constant is change. I remember when he was an infant and I would become exasperated because just when it seemed we'd "figured him out," and knew how to soothe and comfort him, something would change and the old techniques wouldn't work anymore. The changes are different now than they were then, but change is still the constant.

Though I like to think that love is the real constant. Change is inevitable, change is always unfolding -- but our ability to love one another remains. Our sages teach us that this month’s name, Elul / אלול, can be read as an acronym for אני לדודי ודודי לי / “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li,”

I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine. (That’s from Song of Songs.)

The Beloved, in this case, is God; this is our month for remembering

that we can experience God not only as King and Ruler and Judge (the

metaphors so prevalent in the traditional high holiday liturgy) but also

as our Beloved and our Friend. This is the month when God walks in the fields with us, yearning to connect with us Friend-to-friend, Beloved-to-beloved. Life is change, but love always remains.

August 21, 2013

#BlogElul 15: Learn

There's always so much to learn.

There's Torah, and Torah is limitless. Not just the Five Books of Moses, not just the Tanakh (Torah, Prophets, Writings), not just Written Torah + Oral Torah, but the sum total of every text and commentary and insight relating to Torah writ large. Not just the black fire of the letters, but the white fire of the spaces in between.

There's daily life, and daily life is limitless too. I can learn something from everyone I meet. I can learn things from the experience of moving through the check-out line at the grocery store, from every email, from every Tweet and Facebook message, from every person I encounter everywhere I go.

There's the lived Torah of my own human experience, and that grows at the rate of one minute per minute. As each moment unfolds, the Torah of my life can become richer and more nuanced -- or dimmer and more attenuated, depending on the choices I make about how to be in the world.

I want to be someone who learns from every moment. From the sweet and from the bitter. From the joys (new poems, book publications, dinner with beloved friends, my son laughing with delight as he masters a new skill) and from the sorrows (my strokes -- or the brain damage of someone whose blog I've only recently started to read -- or the leukemia battled courageously by a little boy whose journey I follow online every day.) I'm not sure that our joys and sorrows happen in order for us to learn from them, but when we do learn from them, we make meaning in our lives.

I want to find the right balance between Torah learning and life learning, between dedicating myself to the rich and limitless world of my own tradition and to the rich and limitless world of, well, the world. I don't want to forget the breadth and depth of the wide world. I don't want to forget the breadth and depth of my own tradition. And I don't want to overlook the breadth and depth of what I can learn simply from being conscious in my own life. I want to be capable of learning even from my mistakes. Especially from my mistakes. How else will I avoid repeating them when life brings me -- when I bring myself -- to the same circumstances time and again?

There's an old saying that "we teach best what we most need to learn." What will I teach during the coming year? What is the learning I will need to integrate during 5774 in order to be the Rachel I most need (the world most needs me) to be? What will I need to learn this year?

Related: Balancing learning and work, 2008.

August 20, 2013

Essay and postpartum poems at Postpartum Progress

When I look back now, I can’t believe it took me so long to recognize the postpartum depression for what it was. Sure, I felt hopeless and overwhelmed and I cried a lot, but I was a new mother, sleeping in 45-minute increments; surely that was how every mother of a newborn felt? My old life was over and would never come back; I just needed to accept that, or possibly to grieve it for a while. But the grieving didn’t end, and the acceptance didn’t come.

Before our son was born, I had been a poet and rabbinic student. I

struggled, once he was born, to figure out how to hold on to those

identities. When he was two months old I would enroll in one single

rabbinic school class. But before that, I wrote poems. Not very many of

them, but I wrote them. This sounds melodramatic now, but when I was

writing them I felt as though I was saving my own life....

My thanks are due to Katherine Stone at Postpartum Progress not only for her amazing blog and resource site, but also for publishing my guest post Unfold: Poems of Postpartum Depression, excerpted above.

My thanks are due to Katherine Stone at Postpartum Progress not only for her amazing blog and resource site, but also for publishing my guest post Unfold: Poems of Postpartum Depression, excerpted above.

My guest post at Postpartum Progress includes short excerpts from some of the poems in Waiting to Unfold, my second book-length collection of poems, published this year by Phoenicia Publishing and available both from Phoenicia and from Amazon.

If you don't already have a copy, I hope you'll consider buying one -- for yourself, for a new mother in your life, or for anyone you know who has struggled with depression and might find hope in this chronicle of motherhood and charting a new path through.

#BlogElul 14: Remember

There's an exercise I like to do during meditation on Friday mornings. I invite us to look back on the week now ending, starting with the first day of the week -- on the Jewish calendar, Sunday. What was Sunday like? What happened on that day? What was bitter, what was sweet? What do you want to lift up and be grateful for, and what do you want to release and let go?

And then we repeat the process with Monday -- Tuesday -- Wednesday -- all the way up to the present day, the cusp of Shabbat.

I like that meditative exercise because it gives me an opportunity, before Shabbat begins, to reflect on the week which is about to end. To mindfully move through what I can remember of that week; to express gratitude for the places where I lived up to my own expectations; to notice the places where I missed the mark, and set the intention of doing better next week. That's one of the wonderful things about cyclical time: this particular week will never come back again, but there will always be another.

It's more difficult to do this practice with a whole year. I can't remember every day of 5773, even if I tried. But I can do this practice writ large, on a macrocosmic scale. What are the themes of the year now ending? Where are the big-picture places where I lived up to my hopes for myself, and where are the big-picture places where I missed the mark?

What do I remember when I think back on the year which will soon be ending? The high holidays from last year -- the sweetness of reaching the end of Yom Kippur -- my son delighting in our sukkah. Travel to Texas to see my family, to Colorado and later to New Hampshire to see my ALEPH community, to Rhode Island this summer with our son. The winter's worth of snows and cosy wood fires and savory stews with friends. Purim, Pesach, the Omer. The mud and forsythias and daffodils of spring. Our son turning three, and growing to approach four. This summer's sights and sounds and scents and connections. Countless tiny experiences of compassion and kindness (both given and received)...balanced by countless times when I was impatient, or thin-skinned, or not as kind as I intended to be.

My task now: to lift up the things I want to sanctify and remember -- and to let go of the places where I fell short of my own expectations. To recognize the gifts in the sweet places -- and the gifts in the bitter places, too. To remember 5773, with willingness to let it slide into the past as I prepare for 5774.

When you look back on the year which will end with the next new moon, what do you remember?

August 19, 2013

#BlogElul 13: Forgive

Please be aware that this post mentions a parent mistreating a child, and makes references to addiction and infidelity. If that's likely to be triggering for you, please read with care.

Please be aware that this post mentions a parent mistreating a child, and makes references to addiction and infidelity. If that's likely to be triggering for you, please read with care.

I have a memory from my chaplaincy training at Albany Medical Center. I was sitting with my colleagues, a mixed group of ten clergy and laypeople from a wide variety of traditions, and we were exploring together the question of how to extend pastoral care to someone who had done something terrible. Is it our job, as clergy, to extend forgiveness? What if the patient is near death; does that change anything for us? What if the person to whom we are ministering has done something we feel is unforgivable?

Hospitals are holy places in part because they bring us into contact with life and death, with sickness and health, and those in turn connect us with fears and anxieties which most of us keep submerged most of the time. I remember a lot of pre-surgical patient visits where the patient wanted to talk with me about regrets, about fears, about broken relationships, about hurts both inflicted and received. In Talmud there is a teaching that one should make teshuvah (repent/return) the night before one's death -- and, of course, since one never knows when one's death may be, one should make teshuvah always. The night before a surgery can awaken a deep need to make teshuvah -- and also to struggle with forgiveness, both given and received.

As a chaplain, I understood my job to be primarily about presence. Being present to whatever was being expressed, and to the unique human being who was expressing it. The phrase I used a lot that year was "Manifesting the listening ear of God." But sometimes what we hear, when we listen to the people we care for, can challenge us. Sometimes it triggers us, pushes our buttons, raises our own mental and emotional stuff. There are rules about when we, as clergy, have to report something we've learned in a pastoral visit. (For instance, cases of abuse.) But there are also times when we hear things which don't require reporting, but do require some inner work. Often the challenge is simply to sit with something painful, and to figure out how to respond with compassion both to those who have been hurt, and to those who have inflicted hurt on others.

I remember studying texts in hashpa'ah (spiritual direction) classes about the power of forgiveness, and the ways in which forgiving someone who has hurt one can create a spiritual opening not only for that person (who needs forgiveness in order to move on) but also for the person who has been hurt. Holding a grudge is a constricting spiritual posture; it keeps me clenched-up, metaphysically speaking. Offering forgiveness allows me to release myself from that position. I'm reminded of this every time I have the opportunity to recite the deathbed vidui with someone or on someone's behalf; and every time I recite the nightly vidui; and every time Yom Kippur rolls around. Making a spiritual practice of forgiveness changes me, shapes me in ways I find meaningful and valuable.

And yet. And yet -- there are also times when I can't authentically offer forgiveness. For instance: I have a dear friend who was abused by a parent. When I think of what my friend has gone through, the protective instinct in me wants to wrap my righteous anger around my friend like a shield. I don't want to try to forgive. There's precedent for that kind of sentiment in my tradition. I think of the story (recounted in this collection of Jewish teachings about repentance) about Simon Wiesenthal refusing to forgive a Nazi when that Nazi was dying. The only people who could have forgiven that Nazi were those whom he had killed, and his repentance came too late for them. There is a sense in which it's not my place to offer forgiveness for a wrong which wounded someone else.

Though no merit of my own, I have the privilege of exploring these questions from a distance. These are intellectual and spiritual questions for me, not embodied ones. When I talk about extending forgiveness to those who've hurt me, that might mean someone who was mean or disrespectful, someone who said something unkind, someone who insulted me or my passions -- not someone who physically struck me or abused me. I'm endlessly grateful for that, and I'm also aware that that distance is a luxury. I honor those whose struggle with this is far more visceral than my own, and I respect those who argue that for their own health and wellbeing, they choose not to forgive those who have harmed them.

Forgiveness, as I understand it, does not mean condoning. It does not mean letting someone off the hook. For me, forgiveness means creating a kind of emotional and spiritual opening in myself which allows me to relate to others in a different way. It's a practice, and like any other practice, I find that it takes work and that I'm not always good at it. Just like with my mindfulness practice and my gratitude practice, I try, sometimes I fail, I try again.

We read in the Talmud that for sins between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones -- but for sins between a person and another person, Yom Kippur does not atone until the person has truly sought forgiveness from the person they have wronged. The tradition also teaches that it's cruel to withhold forgiveness from someone who has repented of their misdeeds, and that the withholding of forgiveness is itself a sin, a missing of the mark. Of course, that raises the question: who can tell when someone's repentance, their teshuvah, is real and whole? What if someone's just paying lip service to repentance? This can be particularly difficult to discern in the case of a writer or

teacher or public figure whose misdeeds, and apologies, take place in the public sphere. What if the misdeeds are part of a pattern; does their recurrence invalidate previous assertions of repentance -- or new ones?

I tend to assume it's not my job to assess the authenticity of anyone else's teshuvah. And I recognize, also, that all of us miss the mark -- often in the same ways, repeatedly, because our unconscious patterns bring us back to the same inflection points over and over -- and that it's possible to repent a misdeed and to still wind up repeating it even so. This is maybe most dramatically visible in the case of people who struggle with addiction, or with recurring patterns of infidelity, but it's a human tendency I recognize in subtle ways in my own life too. We all bring ourselves back to the same mis-steps until we do the hard spiritual work of discerning what in us needs to change. And sometimes even then, we bring ourselves back to those same well-trodden paths again. In spiritual life, we're always noticing where we are, correcting course, starting over. And over. And over.

In the Chabad tradition, there's a teaching that forgiveness has three steps. First: you stop wishing the person harm, and you pray for their wellbeing, even if you are still hurt and angry. Second: you let go of all anger and resentment toward that person. Third: you restore the relationship. (See Rabbi Michoel Gourarie's essay Must I forgive everyone?) Of course, as even Rabbi Gourarie acknowledges, some relationships shouldn't be restored. Where there is abuse, where there is toxicity, one needs to have the gevurah to maintain good boundaries. But I find meaning in the idea that even in the case of (God forbid) a rapist or an abuser, even when someone else has been harmed and it is not my prerogative nor my place to grant forgiveness, I can still aspire to not wish the wrongdoer harm. I can school myself in the practice of praying for the wellbeing even of those who have done awful things.

Thinking back to the conversation among my chaplaincy cohort: I remember our supervisor suggesting that ultimately forgiveness isn't our job -- it's God's. Reflecting on that, I find myself thinking about a variety of Hasidic teachings which hold that the binaries of good and evil are inextricably bound up with our limited human perspective, but from God's vantage (as it were) a different kind of love and forgiveness are possible. Each year on Yom Kippur night, as we recite the Kol Nidre prayer, we encounter the words וַיֹּֽאמֶר יְי סָלַֽחְתִּי כִּדְבָרֶֽךָ / vayomer Adonai, salachti kidvarecha -- "And God said: I have forgiven you, as you have asked." When we come before the One with open hearts, with a genuine yearning for forgiveness, I believe that that God always forgives. Which, again, doesn't mean condoning wrongdoing. It's more of an existential statement about the kind of God I believe in. The God in Whom I believe can forgive even when I can't.

I'm not always able (or entitled) to forgive. But I aspire to live in a spirit of forgiveness. And I believe that it is my job, as a rabbi and as a human being, to try to extend compassion as best I can -- both to those who miss the mark in horrendous ways, and to those who are harmed by others' missing of the mark. All year long, though maybe especially now, as we move through this season of focusing on our own teshuvah.

Here's an essay on forgiveness by someone I really admire: The Ancient Heart of Forgiveness by Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield.

August 18, 2013

#BlogElul 12: Trust

After the sutures

Everyone falls down.

No one enjoys the aftermath.

But the real test

comes after the sutures --

the chance to thank the surgeon

who did his quiet work

despite the imprecations

and the thrashing.

Sometimes when I miss the mark

I flail and lash out

just like our three-year-old.

But when I calm

I remember how to thank You

for my mistakes, even when they hurt

for Your messengers who cradle me

for the mountains and the moon

for my son's long body nestled

into me like a crane

for Your arms and heart

holding me together

on the days when I break

and the days when I am whole.

I started working on this post after our son got stitches, late last month. (He's fine! He just took a tumble, as very active kids are wont to do, and needed a few stitches on his chin.) What amazed me about the experience of taking him to the emergency room is that while he clearly had a tough time with the actual stitches (and who wouldn't?), as soon as the suturing was over, he calmed down, and as we left the E.D., he thanked every doctor and nurse "for fixing my boo-boo." It's incredibly powerful for me that our son says thank you after a traumatic experience like getting sewn up -- even though he didn't enjoy the stitching, he understood deep down that these people were there to help him, and that when people help you, you say thank you.

I started working on this post after our son got stitches, late last month. (He's fine! He just took a tumble, as very active kids are wont to do, and needed a few stitches on his chin.) What amazed me about the experience of taking him to the emergency room is that while he clearly had a tough time with the actual stitches (and who wouldn't?), as soon as the suturing was over, he calmed down, and as we left the E.D., he thanked every doctor and nurse "for fixing my boo-boo." It's incredibly powerful for me that our son says thank you after a traumatic experience like getting sewn up -- even though he didn't enjoy the stitching, he understood deep down that these people were there to help him, and that when people help you, you say thank you.

I'm sharing this poem today as part of #BlogElul -- you can find other posts on this theme by searching with that hashtag.

August 17, 2013

#BlogElul 11: Count

Our tradition gives us two seasons of counting. In the (northern hemisphere) spring we count the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, also known as the Omer. As we count the Omer, we connect our festival of liberation with our festival of revelation. It's an opportunity to be mindful of the passage of time, and also to do the important spiritual work required each year to get us into the right spiritual and emotional space to receive revelation anew.

Our tradition gives us two seasons of counting. In the (northern hemisphere) spring we count the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, also known as the Omer. As we count the Omer, we connect our festival of liberation with our festival of revelation. It's an opportunity to be mindful of the passage of time, and also to do the important spiritual work required each year to get us into the right spiritual and emotional space to receive revelation anew.

And in the (northern hemisphere) late summer / early autumn we count 49 days between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah. (This is why my friend and colleague Shifrah Tobacman's book of poems is called Omer/Teshuvah -- turn it one way and you can use each poem as a daily meditation for the Omer count; turn it the other way, and you can use each poem as a daily meditation for the journey to Rosh Hashanah.)

Another interpretation: instead of counting the 7 weeks between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah, some count the 40 days from Rosh Chodesh Elul (the first day of the month of Elul) until Yom Kippur. The number forty has special significance in the rabbinic imagination. Forty were the days of the Flood, forty were the days Moshe spent atop Sinai; forty are the weeks between conception and birth (well, more or less -- that's how the sages of our tradition understood it, anyway) -- so forty can represent the transition from one stage into the next. A kosher mikvah must contain forty measures of water, and as a mikvah purifies the one who immerses in it wholly, so can this time of year purify we who immerse in it wholly.

What's the point of all of the counting? Is it just another opportunity to exercise our uniquely Jewish form of something akin to O.C.D? I don't think so -- or at least I don't think that's all it is. We count the days between one thing and the next because that helps us stay situated in this moment in time. The counting can help us combat the tendency to draft either into the remembered past or into the anticipated future. Beyond that, it links us both with that past and with that future. Today is the eleventh day of Elul. We've been trying to do the work of teshuvah for eleven days: how's that working out for us so far? We have the rest of Elul for our internal work, and then the ten first days of Tishri for external work, repairing our relationships with others and with the world. When we count the days, we keep track of where we are -- how far we've come -- and how far we have yet to go.

August 15, 2013

#BlogElul 9 - Hear

I try to really hear the voice of my child. Sometimes he has things to tell me -- about his day at preschool, about Curious George or Diego, about a favorite songs. Sometimes he has sorrows to pour forth, as when he's not allowed a snack right before dinner. Sometimes he wakes in the night with a scary dream (usually about a frog on his bed. I'm not sure why.) I try to listen to him as best I can. I want him to know that his voice matters to me; that his ideas matter to me. That he matters to me.

I try to really hear the voice of my child. Sometimes he has things to tell me -- about his day at preschool, about Curious George or Diego, about a favorite songs. Sometimes he has sorrows to pour forth, as when he's not allowed a snack right before dinner. Sometimes he wakes in the night with a scary dream (usually about a frog on his bed. I'm not sure why.) I try to listen to him as best I can. I want him to know that his voice matters to me; that his ideas matter to me. That he matters to me.

I try to really hear the voices of my congregants. Often they have things to tell me -- about what's happening in their lives, about their hopes and their fears, about their children or their parents. Sometimes they have sorrows to pour forth, or joys to share. Sometimes they bring budgets or board business to discuss. No matter what, I try to listen to them as best I can. I want them to know that their voices matter to me; that their ideas matter to me. That they matter to me.

I try to listen to the people I encounter every day. In person, whether at the CSA or the grocery store; online, on blogs and Twitter and Facebook. It can be easy to forget that there is a human being behind every online interaction, but of course there is; the internet is just another tool for the ordinary and extraordinary communications which mark every day of human life. Sometimes the people I meet have sorrows to pour forth. Sometimes they have joys to share. I try to listen as best I can. I want them to know that their voices matter to me; that their ideas matter to me. That they matter to me.

When I think about hearing Jewishly, I think of the shema. "Hear, O Israel; Adonai is our God; Adonai is One." (That's the first line -- the prayer continues from there, but that one sentence is the ikkar, the essence.) I've been in services where we're encouraged to replace "Israel" with our own names. Praying the words with my own name swapped in for the communal name "Israel" has been surprisingly powerful for me. Recognizing that this isn't just a generalized call for our community to hear the Oneness of all things, but a call for me, specifically, to listen to God's voice and experience unity...! Holy wow. I love that my tradition calls on me not only to listen but to hear.

During this month of Elul, what kind of hearing can I do? In listening to my child -- in listening to my congregation -- in listening to the people I meet every day -- in listening for the voice of God -- there are opportunities for teshuvah, for repentance and return. I always aspire to listen wholly...and I often fail at that aspiration. It's all too easy to be not entirely present: to my child, to my community, to the people I meet, to God. All I can do is notice when I'm not wholly listening, and take a deep breath, and strive to do better. I want to really listen when the world speaks.

Related: Kol Echad: the voice of the one in the voices of the many, July 2013.

Also worth reading: Shema: Hear! Listen! by Gloria Scheiner at The Jewish Writing Project.

August 12, 2013

#BlogElul 18: Pray

One of the things I love about Selichot services, which we hold in my shul (as in many shuls) on the Saturday night closest to Rosh Hashanah, is the chance to immerse in the melodies and themes of the Days of Awe again.

For those who recite the prayers of tachanun regularly during the year, and/or who recite a vidui prayer as part of the bedtime shema, some of the petitionary prayers in Selichot are regular companions. But for many of us, Selichot is the first opportunity of the year to encounter some of the beloved melodies and themes and words we haven't heard since last Yom Kippur came to its close. These are some of my favorite prayers in our vast and deep liturgy.

"Return again, return again, return to the land of your soul..." This short prayer is one I first learned at the old Elat Chayyim in Accord, New York, when I went there for a Shabbat Shuvah retreat in 2003. I remember feeling that I was returning again to the home of my soul on at least two levels: returning to Elat Chayyim and to the presence of my Jewish Renewal community felt like a return, just as returning to the Days of Awe was a return. At that moment in time, I was still so amazed to discover that I could come home in a spiritual sense that every time I did come home in that way, it moved me to tears.

"Adon ha-slichot..." I think I first learned this one at the Brookline Havurah Minyan, back when I used to go there with my sister and her family on Yom Kippur, years and years ago. I love the sinuous Middle Eastern melody I learned there for this old piyyut. It translates to something like, "Master of forgiveness,

examiner of hearts, revealer of depths, declarer of righteousnes -- we have sinned before You; have mercy on us!" It's an alphabetical acrostic, an A-to-Z of pleading for forgiveness. God, with every letter of the alef-bet, with everything in us from beginning to end, we yearn for Your forgiveness. What could be a better melodic reminder of the themes of this season writ large? We have missed the mark. We yearn for closeness with our Source.

"Ana b'koakh, gedulat y'mincha, tatir ts'rurah..." We've been using this one at my shul for Selichot services for some years now. This prayer is much beloved in Jewish Renewal, I think because of our neo-Hasidic roots. Our beloved teacher Reb Zalman comes from a Chabad lineage, and in the Hasidic world this prayer has many purposes and uses. This whole prayer is considered to be one long mystical Name of God. And it asks God -- in Reb Zalman's singable English translation -- "Source of mercy, with loving strength, untie our tangles!" I love the way it names God not as the source of justice (a common metaphor at this time of year) but as the source of mercy -- and the idea that God can untie our tangled places is incredibly resonant for me as we move through this season of teshuvah.

"Achat sha'alti, me'eit Adonai, otah avakesh..." This is probably the prayer I've known the longest in my Jewish Renewal life. During my first week-long retreat at the old Elat Chayyim in 2002, I attended morning services every day. During that week we moved into the month of Elul, so we sang this excerpt from psalm 27 every day, since reciting this psalm daily during Elul is customary in Jewish tradition. I had never heard the psalm before that week. By the end of the week, the melody had become one of my touchstones, something to which I could return when I wanted to be more connected with God. Every year I rejoice when it's time to start singing it every day again.

These are prayers -- not necessarily prayer, if you take my meaning. Which is to say: these prayers are beautiful containers into which one can pour the innermost prayers of one's heart. My teacher Reb Zalman (Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi) likes to say that our written liturgy is like a cookbook; it's a collection of recipes for spiritual experience. But in order to make the recipes, you have to add ingredients; in order to make the prayers real, you have to add your own heart and soul and being.

The prayer of this time of year -- for me -- is this:

Ribbono Shel Olam, Master of the Universe!

Shekhinah, Source of all Being!

I miss You. I miss closeness with You.

I have missed the mark. I've allowed myself to become distant from You.

Forgive me. Embrace me.

Help me know that I am forgiven and that I can try again.

That is my heart's prayer.

Related: A short service for Selichot, 2012; Petition: A Prayer for Selichot, 2009.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers