Calum Chace's Blog, page 20

May 16, 2015

Professor Stuart Russell’s talk at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risks

Professor Stuart Russell, computer science professor at University of California, Berkeley, gave a clear and powerful talk on the promise and peril of artificial intelligence at the CSER in Cambridge on 15th May.

Professor Stuart Russell, computer science professor at University of California, Berkeley, gave a clear and powerful talk on the promise and peril of artificial intelligence at the CSER in Cambridge on 15th May.

Professor Russell has been thinking for over 20 years about what will happen if we create an AGI – an artificial general intelligence, a machine with human-level cognitive abilities. The last chapter of his classic 1994 textbook Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach was called “What if we succeed?”

Although he cautions against making naive statements based on Moore’s Law, he notes that progress on AI is accelerating in ways which cause “holy cow!” moments even for very experienced AI researchers. The landmarks he cites include Deep Blue beating Kasparov at chess, Watson winning Jeopardy, self-driving cars, the robot which can fold towels, video captioning, and of course the Deep Mind system which learns how to play Atari video games at superhuman level within a few days of being created.

Until fairly recently, most people did not notice the improvements in AI because they did not render it good enough to impact every day life. That threshold has been crossed. AI is now performing at a level where small improvements can add millions of dollars to the bottom line of the company which introduces them. After self-driving cars, he thinks that domestic robots will be the Next Big Thing.

Professor Russell claims it is no exaggeration to say that success in creating AGI would be the biggest event in human history. He argues that pressing ahead without paying attention to AI safety on the grounds that AGI will not be created soon is like driving headlong towards a cliff edge and hoping to run out of petrol before we get there. The arrival of AGI, he says, is not imminent, and he won’t be drawn on a date: we can’t predict when the breakthroughs which will get us there will happen, he insists. But they might not be many decades away. Facilities like Amazon‘s Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2) keep changing the landscape.

The risk in superintelligence, he thinks, is less from spontaneous malevolence than from competent decision making which is not wholly based on the same assumptions that we make. His hunch is that achieving Friendly AI by constraining a superintelligence will not work, and instead we should work on directing its motivations – solving the value misalignment problem, he calls it. He is hopeful about techniques based on the idea of inverse reinforcement learning.

Professor Russell argues that AI researchers need to expand the scope of their work to embrace the Friendly AI project. Civil engineers don’t fall into two categories: those who erect structures like buildings and bridges, and those who make sure they don’t fall down. Similarly, nuclear fusion research doesn’t have a separate category of person who studies the containment of the reaction. So AI researchers should not just be working on “AI”, but on “provably beneficial AI”.

He urges the whole AI community to adopt this approach, and hope that AAAI’s willingness to debate autonomous weapons in January means it is relaxing its opposition to involvement in any kind of ethical or political debate.

May 9, 2015

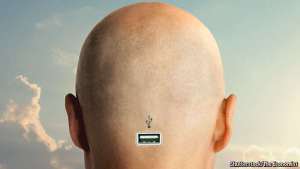

The Economist’s curious articles on artificial intelligence

The Economist is famous for its excellence at forecasting the past and its weakness at forecasting the future.

The Economist is famous for its excellence at forecasting the past and its weakness at forecasting the future.

Its survey on AI (9th May) is a classic. The explanation of deep learning is outstanding, but the conclusion that we should not worry about superintelligence because today’s computers have neither volition nor awareness is, well, less impressive.

The magazine’s leader seems to agree, saying that “even if the prospect of what Mr Hawking calls “full” AI is still distant, it is prudent for societies to plan for how to cope”. But it then goes on to make the outlandish claim that this “is easier than it seems, not least because humans have been creating autonomous entities with superhuman capacities and unaligned interests for some time, [namely] government bureaucracies, markets and armies.”

Must try harder.

April 25, 2015

Ultron – not the new Terminator after all

Film number two in Marvel’s Avengers series is every bit as loud and brash as the first outing, and the crashing about is nicely offset by the customary slices of dry wit, mainly from Robert Downey Jr’s Iron Man. Director Joss Whedon demonstrates again his mastery of timing and pace in epic movies, with audiences given time to breathe during brief diversions to the burgeoning love interest between Bruce Banner and the Black Widow, and vignettes of Hawkeye’s implausibly forgiving family.

Film number two in Marvel’s Avengers series is every bit as loud and brash as the first outing, and the crashing about is nicely offset by the customary slices of dry wit, mainly from Robert Downey Jr’s Iron Man. Director Joss Whedon demonstrates again his mastery of timing and pace in epic movies, with audiences given time to breathe during brief diversions to the burgeoning love interest between Bruce Banner and the Black Widow, and vignettes of Hawkeye’s implausibly forgiving family.

The film is great fun (especially on an IMAX screen) and does pretty much everything that fans of superhero movies want. The story makes sense (more or less) and the script is tight; the actors are engaged, and look as if they enjoyed the process. Of course there is too much CGI; of course the whole thing is a pointless over-sized sugar rush; of course the fight scenes are too kinetic and little human things like pain and broken skin have been airbrushed out. You expect all that; complaining about it is like criticising Jane Austen for a lack of exploding helicopters. If you like superhero movies, you will leave the cinema with a silly grin; if not, then maybe with a superior sneer.

But the movie does have one surprising mis-fire. Whedon had an opportunity to craft a powerful new icon – the artificial intelligence bogeyman for our era, replacing Arnie’s Terminator, which has occupied that role for more than three decades now. The trailers suggested that he had succeeded. Ultron’s sinister Pinocchio parody contains the seeds of genuine horror, and the scene where he starts to “monologue” (which movie baddies do much less since The Incredibles lampooned it so well back in 2004) merely as a cover for a surprise attack is sarcastic repartee worthy of his mentor, Iron Man.

Unfortunately these trailered scenes are pretty much Ultron’s only good ones. After that he comes across as more of a sulky teenager than a dark and near-omnipotent threat. Despite being supposedly an awesome superintelligence, he is repeatedly out-manoeuvred by muscle-bound and not terribly smart humans. He has one Big Idea, which is (spoiler alert) to pick up a city in Eastern Europe and drop it back down on the Earth to create an extinction event like the one that killed the dinosaurs. He risks everything on this one rather fragile plan and when it is foiled he has nothing left in reserve. It doesn’t help that his name sounds like a washing powder.

Avengers: Age of Ultron is a well-made, hugely enjoyable film, but it missed an opportunity to be an iconic, cult movie.

April 19, 2015

Ultron, the new Terminator?

Avengers, the Age of Ultron opens in the UK later this week, and in the US the week after. Apparently Hollywood can forecast a film’s takings pretty well these days (thanks to clever AI algorithms, no doubt) and it seems the studio is quietly confident it’s going to overturn box office records.

Avengers, the Age of Ultron opens in the UK later this week, and in the US the week after. Apparently Hollywood can forecast a film’s takings pretty well these days (thanks to clever AI algorithms, no doubt) and it seems the studio is quietly confident it’s going to overturn box office records.

It may also overturn something else: the unwritten law that every article about the future of artificial intelligence has to be accompanied by a picture of Arnold Schwarzenegger, or the killer robot he played. The original Terminator movie was released in 1984, and 31 years is a great innings. Now Ultron the Marvel super-baddy may well become the new iconic image of a rogue AI.

Ultron, an AI created by Iron Man, has been a key character in Marvel comics for years, but he is new to movie audiences. He arrives at an interesting time: during the Terminator’s tenure, the public has not taken seriously the idea that intelligent machines could become a threat to mankind. Now, thanks to the amazing advances in weak artificial intelligence, and specifically due to the publication last year of Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence, that idea is treated with less disdain.

The growing awareness that AI is an increasingly powerful technology which can have negative as well as positive consequences is to be welcomed. But there is a danger that only the negatives will be understood. In a world of short attention spans where good news is no news, there is a danger of an ill-considered backlash against AI research. That could deprive us of the tremendous benefits that AI can bring us in the years ahead, and in the worst case could drive AGI research underground, to the detriment of the Friendly AI work which we need to accompany it.

Science fiction books and movies provide us with vivid metaphors – shorthand for future scenarios. To have the nuanced, thoughtful debate that we need to have about AI we need a wider range of metaphors. Ultron should provide lots of fun, but nuance…? Probably not so much.

April 16, 2015

On killer robots

The Guardian’s editorial of 14th April 2014 (Weapons systems are becoming autonomous entities. Human beings must take responsibility) argued that killer robots should always remain under human control, because robots can never be morally responsible.

The Guardian’s editorial of 14th April 2014 (Weapons systems are becoming autonomous entities. Human beings must take responsibility) argued that killer robots should always remain under human control, because robots can never be morally responsible.

They kindly published my reply, which said that this may not be true if and when we create machines whose cognitive abilities match or exceed those of humans in every respect. Surveys indicate that around 50% of AI researchers think that could happen before 2050.

But long before then we will face other dilemmas. If wars can be fought by robots, would that not be better than human slaughter? And when robots can discriminate between combatants and civilian bystanders better than human soldiers, who should pull the trigger?

To the Guardian’s great credit, they resisted the temptation to accompany the piece with a picture of the Terminator.

April 6, 2015

Comment on On boiling frogs by Calum Chace

There is a great cartoon of a human demonstrating superiority over animals by pressing a button which explodes her head. Unfortunately I can’t find it, which proves that Google’s AI is still far from perfect.

Comment on On boiling frogs by Stephen Oberauer

Curiously, I also wrote about boiling frogs in a novel that I’ve been writing. It’s a problem with human thinking that really bugs me.

Here’s a snippet, in case you’re interested:

When I was thirteen my biology teacher taught us something foolish. She told us that, if one were to place a frog in a pot of cold water and heat it up slowly, the frog would simply croak away happily, enjoying the warmth, thinking about munching on a large, juicy fly, ignorant of the fact that in a few minutes it will be too hot to jump out and will be well on its way to the froggy afterlife.

What somehow managed to slip my teacher’s mind was that some of us mischievous science nerds would consider this an interesting hypothesis not to be believed until it had been thoroughly processed by the scientific method, tested, re-tested, peer reviewed and published. I looked over at Jim who nodded and winked, apparently having the same thought as myself.

After school the two of us wondered off to a nearby pond. With my lunch box in my hand, I quickly captured a frog; a big one, but still agile enough to be able to hop out of a small pot.

When we arrived at my home I explained the experiment to my little brother, who was just as excited about furthering his scientific studies as we were. I poured cold water into a pot and placed it on the cold stove. The silly frog, however, was not very interested in science and decided to hop out of the cold pot before we had turned the stove on at all. Repeating the experiment produced the same results and I came to the conclusion that my teacher had not been very scientific and was merely repeating an old wives’ tale. The experience, however, had not been a failure, because it had helped me to learn a valuable lesson which would keep repeating itself over and over: Frogs are smarter than us.

On boiling frogs

If you drop a frog into a pan of boiling water it will jump out. Frogs aren’t stupid. But if a frog is sitting in a pan which is gradually heated it will become soporific and fail to notice when it boils to death at 100 degrees. This story has been told many times, not least by the leading management thinker, Charles Handy, in his best-selling book The Age of Unreason.

If you drop a frog into a pan of boiling water it will jump out. Frogs aren’t stupid. But if a frog is sitting in a pan which is gradually heated it will become soporific and fail to notice when it boils to death at 100 degrees. This story has been told many times, not least by the leading management thinker, Charles Handy, in his best-selling book The Age of Unreason.

Unfortunately, the story isn’t true. It was put about by 19th-century experimenters, but has been refuted several times since. Never mind: it’s a good metaphor, and metaphors aren’t supposed to be literally true.

The white heat of technology

Metaphorically, we are all in boiling water now, and the heat is technology. Moore’s Law means that computers double their performance every eighteen months, and this drives the exponential improvement in artificial intelligence (AI). Pretty much every adult in the developing world knows that smartphones and other gadgets are getting smarter at an amazing rate, and you don’t hear many people argue that the progress is going to run out of steam any time soon.

But how many people are asking themselves, Where it is all heading? Well, we all lead busy lives, and we know how hard it is to forecast anything, so why bother?

Life on an exponential curve

Unfortunately, most of us don’t yet understand what being on an exponential curve means. People sometimes talk about the “knee” of an exponential curve – the point at which the past looks uneventful and the future looks like a dramatic take-off. But the reality is that you are always at the knee: on an exponential curve, the past always looks flat and the future always looks vertical. When you understand this, it makes the question of where it is all heading a compelling one.

The exponential improvement in artificial intelligence presents us with two important challenges. In the short term it brings us automation, and we don’t yet know whether that will render most people unemployed in the next two or three decades, or whether humans will manage to scamper up the value chain and keep finding new, interesting and lucrative things to do which computers can’t (yet) match. In the longer term it may bring us artificial general intelligence (AGI), and we don’t yet know whether that will be great news or terrible.

Most people aren’t thinking about these things yet: most of us are still like the frog in the slowly boiling water. But in the last year, the publication of Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence has woken quite a few people up to the risks posed by AGI, because leading technologists like Elon Musk and Bill Gates read it and talked about it. The fact that artificial intelligence presents us with great promise but also great challenges is now openly discussed in the mainstream media. So maybe the metaphor works after all: maybe the metaphorical frog will jump out of the metaphorical water.

Out of the pan…

And if it does, where will it jump? Will there be a rational debate about AI? Or will it become another subject where we make up our minds about what should be done before we have a complete grasp of the facts, and then filter out the evidence we receive to exclude anything which challenges our opinion? Our track record isn’t great, and we can’t afford to get this one wrong!

March 28, 2015

Interview on Singularity Weblog

This week I interviewed with Nikola Danaylov, the creator of Singularity Weblog. It was great fun, and quite an honour to follow in the footsteps of his 160-plus previous guests.

We talked about hope and optimism as a useful bias, about the promise and peril of AGI, about whether automation will end work and force the introduction of universal basic income … and of course about Pandora’s Brain.

March 22, 2015

Science fiction gives us metaphors to think about our biggest problems

Science fiction, it has been said, tells you less about what will happen in the future than it tells you about the predominant concerns of the age when it was written. The 1940s and 50s is known as the golden age of science fiction: short story magazines ruled, and John Campbell, editor of Astounding Stories, demanded better standards of writing than the genre had seen before. Isaac Asimov, Arthur C Clarke, AE van Vogt, and Robert Heinlein all got started in this period. The Cold War was building up, but the West was emerging from the destruction and austerity of war, technology was powering consumerism, and the stories were bright and bold and filled with a sense of wonder.

The golden age was followed by an edgier period, as the Cold War got into in full swing. With the surprise launch of Sputnik in 1957, the Soviet Union revealed its disturbing lead in space technology, and a New Wave of writers led by William Burroughs courted controversy, writing about dystopias, sexuality and drugs. Established SF figures like Asimov and Heinlein changed their styles to fit, and innovative new SF authors arrived, including Samuel R Delany, Ursula Le Guin, and JG Ballard.

Cyberpunk burst onto the stage in 1984 with the publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. It was becoming clear that computers were going to play a growing role in humanity’s future, and it is one of history’s nice ironies that Gibson managed to make his online world so compelling when he had no experience of the internet and indeed had hardly ever used a computer.

The twenty-first century is said to be post-cyberpunk, but it is perhaps too early to tell what that means. The themes of cyberpunk haven’t gone away, but space opera has returned. SF has also been infected by fantasy, which has become unaccountably popular. Very talented writers like Hannu Rajaniemi (The Quantum Thief) blend it with their hard science so that it is hard to tell where one stops and the other starts.

One of the biggest themes in today’s SF is the creation of conscious machines. This isn’t new, of course: AI has been an important feature of many of SF’s best-loved books and movies, from The Forbin Project to 2001 to the Terminator series. But writers have often failed to grasp the impact that thinking machines will have – if and when they arrive. Christopher Nolan’s ambitious but flawed film Interstellar was a classic example: fully conscious machines were treated as – and behaved as – bit-part slaves, even though their cognitive capabilities clearly exceeded those of their human masters.

Writers like Will Hertling (the Avogadro series) and Daniel Suarez (Daemon) are finding new ways to explore the question of how humans will fare when the first super-intelligence arrives. Hollywood is joining in, with thoughtful movies like Her, Transcendence and Ex Machina. We need more great stories about artificial general intelligence: coping with its arrival may well be the biggest challenge the next generation ever faces.