Calum Chace's Blog, page 16

September 11, 2016

Bumps on the road to the Economic Singularity (Part 3 of 3)

Peviously on this blogpost…

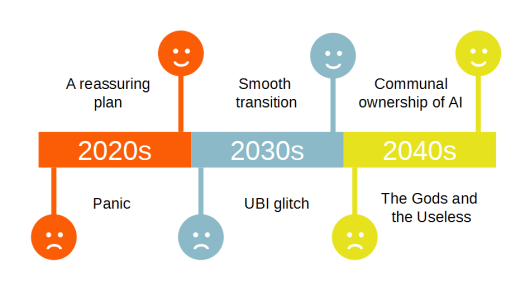

In Part 1 we reviewed the concept of the Economic Singularity, and asked whether automation by machine intelligence will be different from previous rounds of automation. We identified three potential dangers – one for each of the coming three decades. In Part 2 we looked at the dangers in the 2020s and the 2030s. For this rousing finale we look at something that could go wrong in the 2040s. Read on…

3. The 2040s

The danger: the scenario of the Gods and the Useless

It is the early 2040s. For some years, most people have been unemployed, living off a generous UBI funded by taxes on the profits of enormously profitable corporations which deploy impressive AI systems to produce goods and services with great efficiency.

It is the early 2040s. For some years, most people have been unemployed, living off a generous UBI funded by taxes on the profits of enormously profitable corporations which deploy impressive AI systems to produce goods and services with great efficiency.

In most ways, this new economy is a huge improvement on its predecessor. Contrary to the fears that permanently unemployed people would succumb to existential despair or boredom, they play, learn, explore and above all, socialise. Some of them spend most of their waking hours inside VR environments, but these are intensely social experiences, with huge numbers of people all around the world attending concerts, engaged in games, and creating new worlds collaboratively.

Even though very few people still have jobs, the new economy is still a variant on capitalism. Private property remains an essential institution, and people pay for the goods and services with the money they receive in the form of UBI. This means that the corporations which produce the goods and services receive accurate signals about what people genuinely value, and tailor their output accordingly.

The founders and owners of the corporations are stupendously wealthy. Few of the recipients of UBI worry much about this, since they enjoy a good standard of living – better than a middle-class American in the 2010s. Goods and services are cheap and very high-quality, and public infrastructure is well-managed and fit for purpose – thanks in no small part to the internet of things, which (for instance) enables structures to report obsolescence well before damage leads to collapse.

The rate of technological development has not slowed – in fact it has increased, driven by the exponential growth in the power of computers under what is still known as Moore’s Law, even though it has evolved. Until recently, the benefits of this rapid technological progress have spread quickly through the economy. Just as companies made far more money selling smartphones to the majority of the world’s population than they could have done by selling a few diamond-encrusted models to the super-wealthy, so genetic enhancements, nootropics and fancy digital devices have been quickly smeared across the economy.

The wealthy are aware that this is changing: the pace of development is becoming too fast, and new technologies are now supplanting each other before their predecessors are disseminated. This is most noticeable in technologies which enhance human performance, and in particular, their cognitive performance. The wealthy are becoming stronger, faster and smarter than the rest of the population, and the gap is widening.

Thoughtful members of the wealthy realise that this is going to become a problem. They increasingly avoid real-world contact with recipients of UBI, and meet them only in simulated VR environments where their growing difference can be disguised. They spend most of their time in protected enclaves whose whereabouts and whose astonishing defensive capacities are unknown to the rest of the population.

A small group of these wealthy people argue that a difficult choice is looming. The growing separation between the two classes of humans – the Gods and the Useless – cannot remain concealed forever. As they become a different species, this group believes, they will have to choose between explicitly dominating the rest of population, and eliminating them.

The happy scenario: Communal ownership of AI

Soon after the Austrian crisis and the global introduction of UBI, a small group of super-wealthy technology entrepreneurs began meeting to discuss the scenario of the Gods and the Useless. They were determined not to become an isolated minority within their species, feared and hated by the great majority of their peers. They devised a way to transfer their assets into collective ownership, mediated by the blockchain. This, they pointed out, was not socialism or communism, as it did not involve ownership by the state.

They unveiled their plan at the climax of an emotional farewell concert given by a band whose lead singer had recently committed suicide, and it caused a worldwide sensation. Most super-wealthy people immediately pledged to join the action, and they were hailed as heroes by the great majority of the world’s population, although a few isolated groups protested that it was trickery, or some kind of hoax.

September 4, 2016

Bumps on the road to the Economic Singularity (Part 2 of 3)

Peviously on this blogpost…

We reviewed the concept of the Economic Singularity, and asked whether automation by machine intelligence will be different from previous rounds of automation. We identified three potential dangers – one for each of the coming three decades. Read on…

1. The 2020s

The danger: Panic

It is the mid-2020s, and self-driving vehicles (now called “autos”) are widespread. They are well on the way to being universal in commercial vehicles, including trucks, delivery vans, taxis, buses and coaches. As a result most of the five million Americans who used to drive for a living (and the three-plus million whose jobs depend directly on truckers) are now unemployed, and many of them are struggling to find new jobs.

This has not escaped the attention of doctors, lawyers, accountants, factory workers, nurses, short order chefs and gardeners. There is widespread understanding of how powerful machine intelligence has become, and how fast it is still improving. People in every walk of life have realised that their turn is coming – maybe not this year, but soon. They are scared, and wondering how best to position themselves and their families to survive the coming jobs holocaust.

Some of the people who are lucky enough to own their own homes have already started selling them, in order to have as much cash on hand when their incomes dry up. As a result, house prices are tumbling, consumer and business confidence is very low: the world’s largest economies are heading towards a severe recession.

In the absence of a sensible-sounding plan from the incumbent political leadership, populist politicians are gaining strength everywhere, promising impossible rewards for their followers and threatening dire consequences for those who oppose them – at home and especially abroad. We have seen this movie before, and it is not attractive.

The happy scenario: a reassuring plan

Business and political leaders woke up to the possibility of technological unemployment in the second half of the 2010s. It started with a few wild-eyed futurists and writers, and the ideas were taken up by policy wonks and by retired politicians who had nothing left to lose by saying the unsayable. Conferences, colloquia and seminars started to be organised, and pretty soon they were springing up everywhere. Senior executives from the technology giants who were making the intelligent machines got over their reluctance to speculate and address the issue. Economists (but not The Economist) were the last to come around, and as usual they were largely ignored.

Initially, everybody saw the coming changes through the prisms of their pre-existing ideologies and obsessions, but eventually a consensus emerged about the most acceptable outcomes and how to achieve them. People were scared about the future, but not as much as they were excited by it. Humanity had a plan, and we believed in it.

2. The 2030s

The danger: UBI glitch

It is the late 2020s, and everyone accepts that a large majority of people will soon be rendered unemployable by machine intelligence. The debate about how to respond is never out of the headlines of the blogs and the mainstream news media. (Yes, that still exists.) Most people agree that some form of Universal Basic Income (UBI) needs to be introduced. Welfare systems are buckling under the weight of claims by the newly unemployable, and the unemployed are incensed by the poor quality of life that their welfare payments allow.

But not everyone agrees about the wisdom of introducing UBI: the concept has been sullied by a disastrous experiment mounted a few years earlier in Austria. A discredited far-right government was succeeded by a coalition of leftists and techno-optimists, who persuaded their electorate that Austria could blaze a trail for the world and strike a blow against injustice and inequality by unilaterally introducing UBI.

Warnings were sounded both internally and abroad that the result would be a “giant sucking sound”, as all the rich people moved themselves and their assets elsewhere before they could be seized to pay for the UBI. Draconian measures were introduced to prevent capital flight, but were only partly successful, and they led to a collapse of business confidence and investment. The idealistic government pressed ahead, heedless of warnings about an inevitable influx of economic migrants which could not be prevented under the rules of the European Single Market.

Austria’s economy duly imploded, and the government was hounded out of office. The cost to the EU (and in particular, to Germany) of the subsequent rescue was enormous, but the cost to the Austrian people was higher. Another cost was the damage to idea of UBI, and the blow to a consensus which had been developing about the need for it, and how to introduce it.

As the year 2030 approached, many countries were torn by unrest as large numbers of people accustomed to a comfortable life found themselves on the breadline. Thousands were killed in riots, and the severe repression which followed. Eventually, after a series of stumbling crisis talks between political leaders, a global UBI was successfully introduced, funded by taxation of the enormous revenues being generated by the owners of the most advanced AI systems. One of the biggest hurdles to agreement in these talks was that the AI titans were concentrated in the US and China, whose politicians were hard-pressed to overcome the siren call from vocal minorities within their electorates to allow Europe and the developing world find (and fund) their own solutions to the crisis.

The happy scenario: a smooth transition

In its short history, humanity has often repeated the same mistakes – sometimes over and over again. But at times it does respond well to a crisis, and this capability has been enhanced by the advent of worldwide mass communication, especially the Web, and the rise of Big Data and intelligent machines, which enabled us to improve the tracking and analysis of economic and social developments.

As soon as the result of the Austrian elections were known, a small group of world leaders who foresaw the inevitable outcome determined to use it as a prompt for a worldwide agreement on the need for a globally co-ordinated and funded introduction of UBI. The group included the political leaders of the US and China, and also the founders of the biggest AI titans.

As Europe picked up the pieces from the wreckage of the Austrian economy, this group unveiled its proposals, and a grateful world rallied around them.

August 29, 2016

Bumps on the road to the Economic Singularity

A THREE-PART BLOGPOST

PART ONE of THREE

Two Singularities

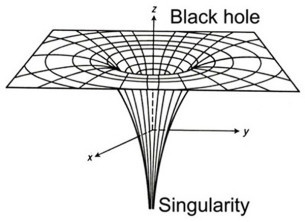

The term “singularity” was first applied to the impact of technology on human affairs back in the 1950s by John von Neuman, one of the founding fathers of computing. He took it from maths and physics, where it means a point at which a variable becomes infinite. The centre of a black hole is a singularity because matter becomes infinitely dense. When you reach a singularity, the normal rules break down, and the future becomes even harder to predict than usual.

Since you are reading this blog, you are probably familiar with the concept of the Technological Singularity, most commonly thought of as the time when artificial intelligence (AI) surpasses humans in cognitive ability and superintelligence arrives on the planet. If you are not familiar with that (and even if you are, to be honest), I humbly recommend my previous book, “Surviving AI”.

The papers these days are awash with articles about a different potential impact of AI: technological unemployment, in which intelligent machines take over human jobs and we all become not only unemployed, but unemployable. Most economists dismiss this as the Luddite Fallacy: we have had automation for centuries, they argue, and it has not caused lasting unemployment. They are of course right about that, but the question is whether it will be different this time. In my new book I argue that yes, it is different this time because this time the machines are coming for our cognitive jobs. And unlike us, they are doubling their capability every 18 months or so.

I also argue that the impact of automation of jobs by machine intelligence will be so profound that it deserves to be called a Singularity – the Economic Singularity

Of the people who do agree with the claim that it is different this time, many are surprisingly relaxed about the outcome. Robots will steal our jobs, they nod happily, and we will all lead lives of leisure, our Universal Basic Income (UBI) funded by the machines’ remarkable (and ever-improving) efficiency in an economy of radical abundance. Instead of spending our days doing jobs which many of us find repetitive and soul-destroying, we can get on with the serious business of playing: learning, exploring, creating, socialising and having fun.

This is an outcome devoutly to be wished for, and I sincerely hope we achieve it because the alternatives are bleak. But I doubt that it will happen by default: getting from here to there will probably require foresight, continuous monitoring and evaluation, planning and talented leadership.

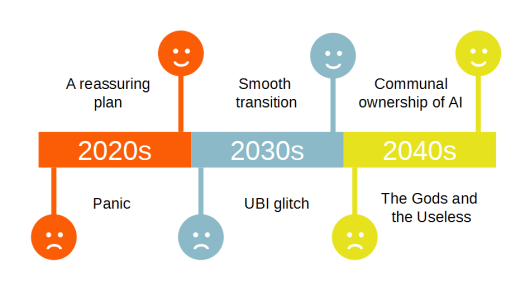

Three dangers

Here are three of the ways that things could go wrong – one for each of the next three decades. To be clear, they are not forecasts, and the timings are just wild guesses. Being an optimistic sort of chap I’m also providing some pointers (“happy scenarios”) to how we can avoid the negative outcomes.

For the 2020s we have panic leading to economic turmoil, which is avoided in the happy version by political leaders demonstrating that they are addressing seriously the potential for an economic singularity, and that they are developing a realistic plan to effect a smooth transition. For the 2030s we have failure to implement UBI effectively leading to widespread deprivation, riots, and a level of social breakdown. In the happy version this is avoided by preparing the ground for the smooth introduction of UBI on a global basis. For the 2040s we have the world descending into the scenario of the Gods and the Useless, a rather brutal phrase I have borrowed from Yuval Harari. This time the happy version involves the super-wealthy agreeing to transfer their assets – especially the AI – into communal ownership mediated by the blockchain.

Next week: The 2020s and 2030s…

August 22, 2016

Auto-cars Assemble!

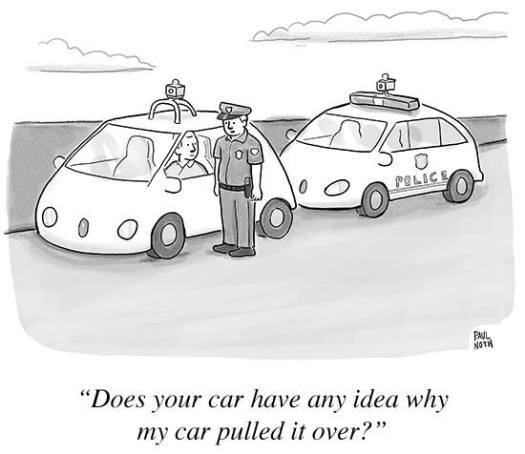

Journalists covering the birth of the self-driving car industry are being kept very busy, and sometimes they must worry if they can keep up with all the new announcements. They haven’t even had time to pause for long enough to give the industry a proper name: “self-driving cars” is too long and too ugly. By way of giving them a helping hand, I’d like to suggest “auto-cars”. That was the name for the horseless carriage adopted by The Times of London newspaper in the late 19th century. Linguistic purists objected that it mixed Greek (auto) with Latin (car), so if anyone still cares about that sort of thing they might prefer to shorten it to “auto”.

Journalists covering the birth of the self-driving car industry are being kept very busy, and sometimes they must worry if they can keep up with all the new announcements. They haven’t even had time to pause for long enough to give the industry a proper name: “self-driving cars” is too long and too ugly. By way of giving them a helping hand, I’d like to suggest “auto-cars”. That was the name for the horseless carriage adopted by The Times of London newspaper in the late 19th century. Linguistic purists objected that it mixed Greek (auto) with Latin (car), so if anyone still cares about that sort of thing they might prefer to shorten it to “auto”.

In the last couple of weeks alone we have seen a series of significant announcements. Uber announced live trials of self-driving taxis in Pittsburgh, thereby enhancing the Steel City’s claims to rival Silicon Valley as the spiritual home of the auto-car. Uber’s legions of self-employed drivers mostly displayed a sort of battle-scarred weary acceptance of their fate as temporary stand-ins for the machines, although Uber’s CEO Travis Kalanick made a brave (some would say risible) attempt to argue that the move to auto-cars will create more jobs than it destroys because machines will not be able to handle all the routes and journeys.

Also in the last fortnight, Helsinki revealed that it is joining a small list of cities trialling driverless buses. Trikala in Greece was the first European city on the list, back in October 2015. Very sensibly, they are proceeding with caution: the robo-buses will hit top speed at a leisurely 10 miles per hour.

An article published this week listed no fewer than 19 car manufacturers, software suppliers and component manufacturers who are committed to having fully automated cars on the road by 2020. Some of them, like Volvo and Tesla, have said they will be ready years before that – if the regulators are.

This raises again the debate about how much automation to offer drivers in the early stages of the auto-car industry. Tesla has been criticised – mostly unfairly – for making its customers complacent about the need to remain vigilant when at the wheel by calling its driver assisting technology Autopilot. When someone is as wildly popular as Elon Musk has (justifiably) become there is bound to be a backlash, and his critics rail against him for putting the safety of Tesla drivers at risk with a “beta” version of the software. Musks’s response has been typically direct and acerbic.

But it is undeniable that humans struggle to pay attention when a machine appears to be doing its job perfectly. Google noticed this when it found the engineers chaperoning its experimental self-driving cars were doing dubious things like turning round to pick up laptops from the back seat while driving along the freeway at 60 miles an hour. Google concluded that self-driving cars should be – at launch – what the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration designates as L4. This means the car’s artificial intelligence can “perform all safety-critical driving functions and monitor roadway conditions for an entire trip”. Tesla’s Autopilot is currently L2, but the company says it will have L4 available in 2018. (L5 means the car has no steering wheel.)

These developments and announcements are all fascinating in their own right, and they certainly keep the journos busy. Collectively, they show that the ecosystem of self-driving cars is becoming varied, and ever more life-like. Only people who are just not paying attention can now deny that the 2020s will the decade of the auto-car.

But what are we to make of it all? Fundamentally, is it a good thing?

Auto-cars will have several profound impacts on humanity. The most important one is that fewer of us will be killed or maimed by cars. Human drivers currently kill 1.2m people a year on the world’s roads, and we injure a further 20 to 50 million. Globally, road traffic accidents are the leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 29, and they cost middle-income countries around 2% of their GDP, amounting to $100 billion a year. We are sending humans to do a machine’s job, and this slaughter cannot end too soon.

A less dramatic but nevertheless profound result will be that commuters will gain time and lose stress. I suspect this will have a bigger impact than we currently realise. One unexpected consequence may be that people will travel around more, as driving becomes less of a tiring chore and more like sitting in your armchair at home: comfortable, and fully in touch with your screens and digital feeds – including virtual reality. No doubt somebody has already written the science fiction story in which many people no longer have homes, but spend their time as nomads in self-driving RVs, slowly touring the world, scheduling frequent rendez-vous with friends in exotic locations, and always plugged into the network.

More prosaically, because AIs will drive more efficiently and safely than we do, they will make more efficient use of space, especially in our cities. Traffic jams and pollution will ease, and if the car-sharing model promoted by Uber and others takes hold, there could be less need for parking spaces, as cars spend less of their time sitting idly in driveways and garages.

For me, though, the most intriguing impact will be that auto-cars will probably cause the first great wave of unemployment caused by machine intelligence. An estimated 3.5m Americans are employed as truck drivers, and it is the most common profession in a majority of US states. There are also 650,000 bus drivers and 230,000 taxi drivers. (This latter figure seems very low considering how many people now make their living by driving for Uber, Lyft and so on.) By 2030, most of these people will have either found a new profession, or they will have joined the long-term unemployed. It is a huge tranche of the working population for the economy to absorb.

As mainstream economists rightly point out, automation has not caused long-term unemployment in the past. In my new book, The Economic Singularity, I argue that it is different this time, and that we need to monitor and prepare.

July 24, 2016

A bet about conscious machines

The estimable Robin Hanson and I are reviewing each other’s books. We disagree with each other about almost everything, which is great. I admire Robin’s ability to disagree strongly without a trace of animosity.

The bet arose because of the following passage in my new book, The Economic Singularity:

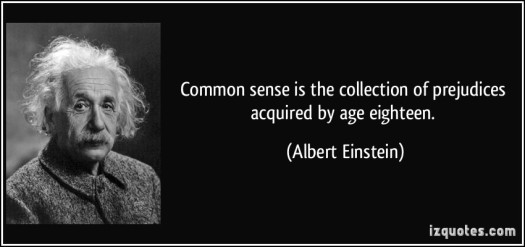

Geoff Hinton – the man whose team won the landmark 2012 ImageNet competition – went further. In May 2015 he said that he expects machines to demonstrate common sense within a decade.

(Here is a report of Hinton saying that.)

Robin is famously sceptical about the rapid progress of AI, thinking it is grossly over-stated. He thinks there is no chance at all that machines will have common sense by 23 July 2026. And so we have agreed a wager. He has generously given me 50-to-1 odds, so if Hinton is wrong I pay Robin $100, and Hinton is right, Robin pays me $5,000. (He’s a tenured professor at a prestigious US university, so that kind of money is loose change to him.)

What do we mean by common sense? I’m not sure it’s a concept capable of precise definition, but you know it when you see it. Here’s one description, from the next paragraph in my book:

Common sense can be described as having a mental model of the world which allows you to predict what will happen if certain actions are taken. Professor Murray Shanahan of Imperial College uses the example of throwing a chair from a stage into an audience: humans would understand that members of the audience would throw up their hands to protect themselves, but some damage would probably be caused, and certainly some upset. A machine without common sense would have very little idea of what would happen.

Rather than try to negotiate a precise definition of common sense, Robin and I have agreed to appoint an impartial judge. We await a response from our first candidate.

To be clear, common sense falls a long way short of consciousness, or of artificial general intelligence.

July 21, 2016

The Economic Singularity – out now!

Artificial intelligence (AI) is overtaking our human ability to absorb and process information. Robots are becoming increasingly dextrous, flexible, and safe to be around (except the military ones). It is our most powerful technology, and we all need to understand it.

In this new book I argue that within a few decades, most humans will not be able to work for money. Self-driving cars will probably be the canary in the coal mine, providing a wake-up call for everyone who isn’t yet paying attention. All jobs will be affected, from fast food McJobs to lawyers and journalists. This is the single most important development facing humanity in the first half of the 21st century.

The fashionable belief that Universal Basic Income is the solution is only partly correct. We are probably going to need an entirely new economic system, and we better start planning soon – for the Economic Singularity!

The outcome can be very good – a world in which machines do all the boring jobs and humans do pretty much what they please. But there are major risks, which we can only avoid by being alert to the possible futures and planning how to avoid the negative ones.

April 23, 2016

Creative Capital at The Hospital

The Ludic Group runs a series of events at London’s Hospital Club, and on the 4th April David Wood, chair of the London Futurists and I gave talks about some of the technologies shaping our future. The video, just 3 mins 45 seconds, is here.

January 30, 2016

ThinkNation talk

ThinkNation is a brilliant initiative. The brainchild of Lizzie Hodgson, it is “where young people, artists and thought leaders tackle how technology is impacting everyday life and shaping our futures.” Given the profound importance of the changes sweeping through our lives in the coming years and decades, there aren’t many more important subjects to address.

ThinkNation is a brilliant initiative. The brainchild of Lizzie Hodgson, it is “where young people, artists and thought leaders tackle how technology is impacting everyday life and shaping our futures.” Given the profound importance of the changes sweeping through our lives in the coming years and decades, there aren’t many more important subjects to address.

So I was very pleased to deliver this talk to an impressive group of 14-18 year-olds in December.

January 27, 2016

The Big Issue

For readers outside the UK, The Big Issue is a street newspaper written by professional journalists and sold by homeless people. It is one of the UK’s biggest social enterprises.

For readers outside the UK, The Big Issue is a street newspaper written by professional journalists and sold by homeless people. It is one of the UK’s biggest social enterprises.

So I am delighted that they commissioned this article about, well … a Big Issue. Click on the logo or the image below to go to the site and read the full article.

January 12, 2016

Letter from Utopia

When Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk and Bill Gates talked about the promise and the peril of Artificial Intelligence last year, the media only heard the peril part. And the Terminator got a new lease of life. Since then a more balanced approach has been settling in.

As a wise and sapient reader of this blog, you already know that those luminaries were prompted to comment on AI by the publication of Nick Bostrom’s book “Superintelligence”. (If you haven’t read it yet, you should.)

Bostrom is often characterised as a doom-sayer, which he categorically is not. Although the New Year fireworks are but a memory, 2016 is still a young year, so I thought I would post this link to an extraordinarily uplifting snatch of optimism that Bostrom posted on his blog back in 2006.

It’s called a Letter from Utopia, and it needs no further introduction.

Click here to read the rest…