Calum Chace's Blog, page 18

October 11, 2015

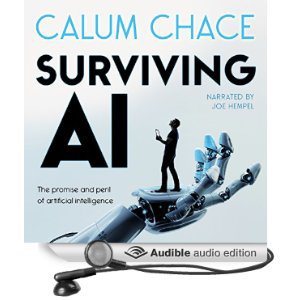

Surviving AI now available as an audio book

Surviving AI is now available at Amazon as an audio book – either as a stand-alone purchase, or (free!) as part of a trial of Amazon’s Audible service.

Surviving AI is now available at Amazon as an audio book – either as a stand-alone purchase, or (free!) as part of a trial of Amazon’s Audible service.

Like Pandora’s Brain, the audio version of Surviving AI is narrated by Joe Hempel, a talented voice artist who is making quite a name for himself in the world of audio books. It is already a best-seller in two categories.

Whether you go to work on the tube or the freeway, turn off the Eagles, and in just four and a half hours, learn all about the promise and peril of our most powerful technology.

October 9, 2015

SwiftKey announces the first neural net on a smartphone keyboard

SwiftKey pioneered keyboards with a three-word suggestion bar above the keys that could accurately predict your next word. This was powered by a technology called “n-gram”, an approach now used on more than a billion devices globally.

SwiftKey pioneered keyboards with a three-word suggestion bar above the keys that could accurately predict your next word. This was powered by a technology called “n-gram”, an approach now used on more than a billion devices globally.

N-gram technology has some limitations, as it can’t capture the underlying meaning of words and can only accurately predict words that have been seen before in the same word sequence. Now, SwiftKey Neural’s intelligent understanding of sentence context introduces a more ‘human’ touch for mobile typing.

Using machine learning and enormous amounts of language data, SwiftKey’s neural model is able to capture the meanings of words and the relationships between them. Within the neural model, words are organised in ‘clusters’, located at varying degrees of proximity to one another.

So, having seen the phrase “Let’s meet at the airport” during training, the technology is able to infer that “office” or “hotel” are similar words which could also be appropriate predictions in place of “airport”. Further, it understands that “Let’s meet at the airport” has a similar sentence structure to “Let’s chat at the office”. This intelligence allows SwiftKey Neural to offer the most appropriate next word based on the sentence being typed.

Until now, neural network language models have been deployed mostly on large servers, requiring significant computational resources. The launch of SwiftKey Neural Alpha is the first time this type of language model technology has been able to operate locally on a smartphone – a huge challenge given the resource constraints.

And the very clever people at SwiftKey reckon they are only scratching the surface of what’s possible with this technology.

October 7, 2015

The new Globalisation: products localise as services globalise

We are used to thinking about globalisation as a phenomenon involving products. Economic liberals see it as a good thing, enabling the law of comparative advantage to improve the lives of people all over the world, and uniting nations in peaceful trade instead of sundering them in war. Their opponents on both the political left and right see it as a bad thing, impoverishing their own citizens as cheap goods flood in from “over there”.

We are used to thinking about globalisation as a phenomenon involving products. Economic liberals see it as a good thing, enabling the law of comparative advantage to improve the lives of people all over the world, and uniting nations in peaceful trade instead of sundering them in war. Their opponents on both the political left and right see it as a bad thing, impoverishing their own citizens as cheap goods flood in from “over there”.

Globalisation is not new. When in 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue, he kicked off a massive wave of globalisation, but it was neither the first nor the last. The phenomenon gathered pace in the decades following World War Two, as economies recovered from war, and new technologies reduced the cost of transport and communication. It accelerated further during the 1970s, as containerisation kicked in, and China adopted capitalism (in practice if not in name).

Globalisation is not new. When in 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue, he kicked off a massive wave of globalisation, but it was neither the first nor the last. The phenomenon gathered pace in the decades following World War Two, as economies recovered from war, and new technologies reduced the cost of transport and communication. It accelerated further during the 1970s, as containerisation kicked in, and China adopted capitalism (in practice if not in name).

But two current technology trends look set to reverse the globalisation of manufacturing and exchanging products. 3D printing has been around for decades, but the lapse of key patents, and the improvements in their software mean that 3D printers are now ready for prime-time. They are being used to build cars, houses, toys, and spare parts for spacecraft. They are still searching for their killer app, and for better ability to use mixed materials, but it is clear that in coming years, many products which would have been manufactured abroad and shipped to a store near you will instead be printed in your own home, or at a neighbourhood 3D printing facility.

The other globalisation-reversing technology is automation. The prices of industrial robots are falling fast, and their safety and user-friendliness is increasing. The competitive advantage of China’s cheap labour is disappearing. It costs the same to buy a robot here as it does there. (China knows this, and is investing in industrial robots faster than anyone else, partly in a bid to make sure its fast-growing domestic consumer market is supplied by Chinese companies rather than foreigners.)

But while globalisation may be going into reverse in products, services are moving in the opposite direction.

Traditionally, services have been local affairs: conceived, negotiated and transacted by people living in close proximity. With a few exceptions (in particular, some financial services) they have been too inexpensive to convey over large distances, and barriers which stood in the way included culture, and the cost and effectiveness of transport and communications.

These barriers are going or gone. The communications revolutions of the 20th century and the powerful global appeal of American culture have plastered a layer of global homogeneity over the world’s multitude of still-vibrant local cultures. Fast-improving bandwidth and interactivity in the internet means that services like media become ever easier to transmit around the world. Virtual reality will sharply accelerate that process.

Professional services like accounting and management consultancy can increasingly be delivered globally. E-commerce continues to take share from the High Street, and artificial intelligence is enabling healthcare and educational services to be delivered remotely, and globally.

As products de-globalise, services are globalising. Something to cheer both the champions and opponents of globalisation, then.

September 30, 2015

Art, creativity, and artificial intelligence

“Art goes beyond creativity, and you have to be conscious to produce it.”

“Art goes beyond creativity, and you have to be conscious to produce it.”

That could be a handy slogan for the forthcoming race against the machines – and it might also be true.

Creativity is the use of imagination or original ideas to create something. Imagination is the faculty of having original ideas, and there seems to be no reason why that requires a conscious mind to be at work. Creativity can simply be the act of combining two existing ideas (perhaps from different domains of expertise) in a novel way.

The eminent 19th-century chemist August Kekule solved the riddle of the molecular structure of benzene while day-dreaming, gazing into a fire. True, he had spent a long time before that pondering the problem, but according to his own account, his conscious mind was not at work when the creative spark ignited. You might argue that Kekule’s sub-conscious was the originator of the insight, and that a sub-conscious can only exist where there is consciousness, but that seems to me an assertion that needs proving.

Can computers be creative? In mid-2015, Google researchers installed a feedback loop in an image recognition neural network, and the result (here) was some fabulously hallucinogenic images. To deny that they were creative is to distort the meaning of the word.

Art is something different. It involves the application of creativity to express something. It might be beauty, emotion, or (my personal favourite) a profound insight into the condition of conscious life. There are probably as many definitions of art as there are people who have sought one, but I suspect that most of us would agree that to qualify as art, a piece of work has to be able to say something to other conscious beings about the experience of the artist. (If that disqualifies a good deal of what is currently sold under the banner of art, then so be it. In fact, three cheers, I reckon.)

To say something about your own experience clearly requires you to have had some experience, and that would seem to require consciousness. Therefore it seems to me that until artificial general intelligence (AGI) arrives, AIs can be creative but not artistic. This in turn means that while Donna Tartt and Kazuo Ishiguro are probably OK for a few decades, Wilbur Smith and James Patterson have chosen the timing of their careers expertly, and their publishers better find something different to do.

September 24, 2015

Artificial novelists

I just finished reading “The Girl in the Spider’s Web”, the fourth book in the Millennium Trilogy by Stieg Larsson, which was made into a great trilogy of films in its native Sweden, and (IMHO) a less good film by Hollywood.

I just finished reading “The Girl in the Spider’s Web”, the fourth book in the Millennium Trilogy by Stieg Larsson, which was made into a great trilogy of films in its native Sweden, and (IMHO) a less good film by Hollywood.

Famously, this fourth book was not written by Larsson, who made the ill-advised career move of dying before his books became huge best-sellers. But (IMHO again) it’s damn good. For me at least, the cast of characters live on. (There is an AGI sub-plot which I think is a bit daft, but it barely distracts.)

The shift in author but the consistency of world-building got me thinking about when an AI will first produce a thriller as good as a human. AIs already produce huge numbers of sports reports and financial reports for AP and others. They’re not going to stop there.

Highly successful writers like Wilbur Smith and James Patterson churn out brilliantly readable books, and some of them have stables of ghost-writers doing the actual drafting. There is a formula to these things, and they work. Readers love ’em.

If and when an AI is first able to write a novel as well as a human, will it quickly figure out how to do it much, much better? I can see no reason why not. Thrillers may become like crack cocaine to avid readers: they’ll forget to eat because they are so engrossed in the story.

When? All forecasts are wrong, of course, and I can only offer a science-free hunch, but I reckon within ten years.

That will be another powerful sign that we are well on the way to the economic singularity I describe in “Surviving AI”.

September 17, 2015

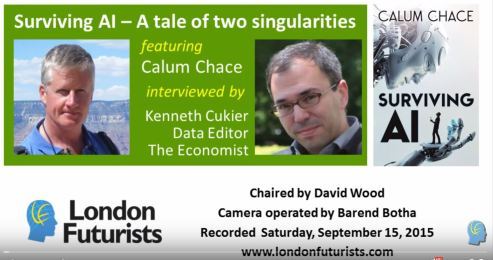

Book launch event for “Surviving AI”

Google kindly offered the use of the conference room at their London Campus for the official launch of “Surviving AI” on 15th September.

Google kindly offered the use of the conference room at their London Campus for the official launch of “Surviving AI” on 15th September.

David Wood, chair of the London Futurist Group did most of the organisation with his usual efficiency and aplomb, and Kenn Cukier of The Economist did a terrific job of compering.

There was a great turnout and a lively discussion after the talk. You can watch the video here, and you can join the discussion here.

September 13, 2015

Interview on Talk Radio Europe

Here’s a link to a 14-minute interview with Bill Padley of Talk Radio Europe, a station for English-speakers in Spain. A tiny bit of research enabled me to illustrate the power of the AI we already have, much to Bill’s delight.

September 9, 2015

Review the Future – podcast interview

A couple of days ago I Skyped with Jon Perry, co-founder and co-host of the excellent Review the Future podcast.

A couple of days ago I Skyped with Jon Perry, co-founder and co-host of the excellent Review the Future podcast.

(I came across this podcast recently when they interviewed Nikola Danaylov of Singularity 1 on 1, and I’ve listened to some of their back catalogue, which I highly recommend.)

Jon and I cantered over much of the subject area covered by “Surviving AI”, and then he edited it so that I didn’t sound like a complete fool. (Thanks Jon!)

And now it’s online and available for your consideration.

September 4, 2015

“Surviving AI” is now available at Amazon!

“Surviving AI”, a non-fiction review of the promise and peril of artificial intelligence is now on sale at Amazon. It’s available in both ebook and paperback formats, and my favourite voice artist, Joe Hempel, is making great strides with the audio version. (Here are Amazon’s UK and US sites.)

“Surviving AI”, a non-fiction review of the promise and peril of artificial intelligence is now on sale at Amazon. It’s available in both ebook and paperback formats, and my favourite voice artist, Joe Hempel, is making great strides with the audio version. (Here are Amazon’s UK and US sites.)

Artificial intelligence is our most powerful technology, and in the coming decades it will change everything in our lives. If we get it right it will make humans almost godlike. If we get it wrong… well, extinction is not the worst possible outcome.

“Surviving AI” is a concise, easy-to-read guide to what’s coming, taking you through technological unemployment (the economic singularity) and the possible creation of a superintelligence (the technological singularity).

Well, that’s what it says on the Amazon site, anyway.

August 31, 2015

Pandora’s Brain is now available as an audio book

The audible version of Pandora’s Brain is now available at your local Amazon store. You can even get it free if you subscribe to Audible’s subscription service.

The audible version of Pandora’s Brain is now available at your local Amazon store. You can even get it free if you subscribe to Audible’s subscription service.

The narrator is Joe Hempel, a very talented voice artist based in the US (see previous post).

In some episodes of Top Gear, the anonymous test driver The Stig listened to audio books while working. I wonder if he now works for the BBC or for Amazon? Anyone got his number?