Calum Chace's Blog, page 15

November 20, 2016

Discussing AI with George Osborne

One of the many worrying aspects of the Brexit referendum in the UK and the Trumpularity in the US is that most politicians are not yet talking about the challenges posed by the coming impact of powerful artificial intelligence. This needs to change.

A conversation I had recently with George Osborne (until recently the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer) gives grounds for hope.

The video below (16 minutes) contains excerpts from a recent panel discussion called “Ask Me Anything About the Future”. Hosted by Bloomberg, it was organised by Force Over Mass, an early-stage investment fund manager. It was very ably chaired by David Wood, who runs the London Futurists meetup group.

The video of the whole event (1hr 39 mins) is here.

November 13, 2016

It’s not the Fourth Industrial Revolution!

Industrie 4.0

Klaus Schwab is a clever man. After a rapid ascent through the ranks of German commercial life, he founded the World Economic Foundation (WEF) in 1971. The WEF is best known for organising a five-day annual meeting of the global business and political elite at the ski resort of Davos in Switzerland. He has a list of awards and honorary doctorates as long as your arm.

Schwab has done much to popularise the notion that we are entering a fourth industrial revolution – not least by writing a book of that name. He didn’t invent the phrase: rather he has broadened the term Industrie 4.0, which was adopted by a group of leading German industrialists in 2012 to persuade their government to help the country move towards “smart manufacturing”, in which artificial intelligence and Big Data are deployed to make production processes more efficient and more flexible.

In that limited context the name makes some sense, but the Fourth Industrial Revolution label is expansionist, and has claimed the Internet of Things, among other aspects of our increasingly AI-affected world. It is a misleading and unhelpful label.

The sixth fourth industrial revolution

Smart manufacturing is not the first development to be called the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As this Slate article from January 2016 points out, it is at least the sixth “fourth industrial revolution”. (The others, since you ask, were atomic energy in 1948, ubiquitous electronics in 1955, computers in 1970, the information age in 1984, and finally, nanotechnology.)

Furthermore, if we are in the business of chopping the industrial revolution into pieces, it is by no means clear that there were only three of them before Industrie 4.0 came along. One of the most helpful ways to understand the industrial revolution is to view it as the arrival of four transformative technologies on the following approximate timeline:

1712: primitive steam engines, textile manufacturing machines, and canals

1830: mobile steam engines and railways

1875: steel and heavy engineering, the chemicals industry

1910: oil, electricity, mass production, cars, airplanes and mass travel

Labelling the Internet of Things, or even smart manufacturing, as the Fourth Industrial Revolution is both confusing and plain wrong. In fact they are both part of something much bigger than another lap of the industrial revolution, momentous as that process was. They are part of the information revolution.

The information revolution

The information revolution begins as information and knowledge become increasingly important factors of production, alongside capital, labour, and raw materials. Information acquires economic value in its own right. Services become the mainstay of the overall economy, pushing manufacturing into second place, and agriculture into third. (Some politicians don’t like this idea, but there is not much they can do about it. You can’t wish manufacturing back into pole position, and trying to legislate it would bring ruin.)

An Austrian economist named Fritz Machlup calculated that knowledge industries accounted for a third of US GDP in 1959, and argued that this qualified the country as an information society. That seems as good a date as any to pick as the start of the information revolution.

Not just semantics

Why is this important? Is it just semantics? No. First, labels are an important part of language, and language is what allows us to communicate effectively, to kill mammoths, and to build walls and pyramids. When labels point to the wrong things, or point to different things for different people, you get confusion instead of communication.

Secondly, the information revolution is the most important event in our species’ short but dramatic history. It is our third great transformative wave. The first was the agricultural revolution which turned foragers into farmers. That gave us mastery over animals, and generated food surpluses which allowed our population to grow enormously. It made the lives of individual humans considerably less pleasant on average, but it greatly advanced the species.

The second, of course, was the industrial revolution, which in many ways gave us mastery of the planet. Coupled with the enlightenment and the discovery of the scientific method, it ended the perpetual tyranny of famine and starvation, and brought the majority of the species out of the abject poverty which had been the fate of almost every human before. For most people in the developed world it created lifestyles which would have been the envy of kings and queens in previous generations.

The information revolution will do even more. If we survive the two singularities – the economic and the technological ones – it will make us godlike. If we flunk those transitions, we may go extinct, or perhaps just be thrown back to something like the middle ages. Since you are reading this it is likely that you know what I am talking about, and understand the reasoning behind these apparently melodramatic claims. Too few of our fellow humans do, and we need to change that. Muddying the waters of our understanding of the information revolution by calling parts of it the Fourth Industrial Revolution does not help.

November 6, 2016

The Simulation Hypothesis: an economical twist (part 2 of 2)

Offending Copernicus

Of course this is all wild and ultimately pointless speculation, so I won’t be at all upset if you decide it is more worthwhile to go watch a game of baseball or cricket instead of reading the rest of this post. But if you’re still with me, then isn’t it a curious coincidence that you happen to be alive right at the time when humanity is rushing headlong towards the creation of AGI and superintelligence? And that you might very possibly be alive to see it happen? Doesn’t that situation offend against the Copernican principle, also known as the mediocrity principle, which urges scepticism about any explanation that places us at a privileged vantage point in time or space within the universe?

Another curious thing about the situation is the extraordinary amount of computronium that our simulators seem to have dedicated to the task of creating our context. That “context” is a universe of 100 billion galaxies each containing 100 billion stars. (Although no aliens, as far as we can tell.) And this universe has been running for 13.7 billion years.

Maybe our simulators have a great deal of computronium lying around, and maybe they don’t perceive time the way you and I do. Maybe they didn’t have to sit around twiddling their (indeterminate number of) thumbs while the earth began to cool, the autotrophs began to droll, neanderthals developed tools, we built a wall, we built the pyramids, and so on. (3)

The economical twist

An alternative possibility to all this expense is that our simulation only appears to have 10,000 billion billion star systems and a 13.7 billion-year history. If you have the capability to create beings like us then you presumably have the capability to convince us of the reality of whatever context you would like us to believe in. And you would save a fortune in time and computronium by faking the context. So if we do live in a simulation that was created for a specific purpose, surely it is more likely that we were created quite recently – maybe only a few minutes ago – kitted out with fake memories and the appearance of an enormous backstory and a vast spacial hinterland?

If that is true, it begs the question of what happens to us after the simulation completes its purpose. Perhaps it gets re-run in order to optimise the outcome. Perhaps it is just switched off and we all go to sleep, dreamless. Or perhaps we have the opportunity to combine our minds with that of the superintelligence that is created, and ascend to the level of the simulators.

Turtles all the way up

Of course the simulators themselves may be going through a similar chain of reasoning about their own existence. Perhaps we are somewhere in the midst of a deep pile of nested simulations, each created by and ultimately dependant on the one above. In a description of our world sometimes attributed to Hindu legend, the earth is a flat plate supported by elephants standing on the back of a tortoise. When asked what the tortoise is standing on, one adherent replied, “it’s turtles all the way down”. (4) Perhaps, in our case, it’s turtles all the way up.

Notes

(3) Big Bang Theory, theme tune

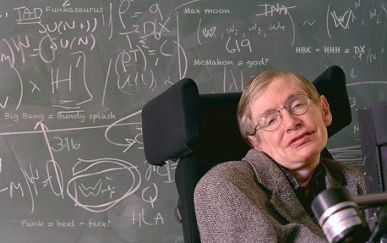

(4) A conversation between Bertrand Russell and an elderly lady mentioned in Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time”

October 30, 2016

The Simulation Hypothesis: an economical twist (part 1 of 2)

Are we living in the Matrix?

Are we living in the Matrix? This question seems futuristic, a theme from a science fiction movie. (Which of course it is.) But the best science fiction is philosophy in fancy dress, and philosophers have been asking the question since at least the ancient Greeks.

The question generated considerable interest in June this year when Elon Musk said the chance that we live in a “base reality” was “one in billions”. But as long ago as 380 BC, when the Greek philosopher Plato wrote “The Republic”, he included the Allegory of the Cave, which argued that men are like prisoners chained to a wall in a dark cave. Their only impression of reality is the shadows cast on a wall in front of them by a fire behind them which they cannot see. If they could see reality in all its true glory it would blind them.

Trilemma

In 2003, the question was given the formal structure of a trilemma (a difficult choice between three options) by the Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom. He observed that we use our technology to simulate worlds inhabited by creatures which are as realistic as we can make them, and that some of the most compelling of these worlds contain people who could be our ancestors. There are many reasons to create these “ancestor simulations”, and a civilisation which could create them at all would create many of them. He concluded that one of these three statements must be true:

All civilisations are destroyed (or self-destruct) before their technology reaches the stage where it would allow them to create ancestor simulations.

Numerous civilisations have reached that stage of technology but they all refrain from doing so, perhaps for moral or aesthetic reasons.

We live in a simulation. (1)

People often that assume that Bostrom argues that we are living in a simulation, but in fact he thinks the self-destruction scenario is also a contender.

Answering Enrico

The simulation scenario and the inevitable demise scenario also both offer plausible answers to Enrico Fermi’s Paradox, the apparent contradiction between the absence of evidence of other intelligent life in the universe, and the high probability of there being lots of it. Maybe civilisations inevitably collapse before they acquire the power to build Dyson Spheres or blurt out Pi in a durable pan-galactic email. Or maybe, like Douglas Adams’ mice (2), the creators of the simulation we live in only needed the one world to achieve whatever goal they had in creating the earth. Populating the universe with teeming swarms of aliens was simply unnecessary, as well as being hideously expensive in computational resources.

Reasons to simulate us

If we do live in a simulation, why was it made? If the sole purpose was entertainment then the prevalence in our world of torture, child leukemia and much else makes it hard to avoid concluding that our creator was either incompetent or callous. (Conscientious theists have to wrestle with a fiercer version of this problem known as the Problem of Evil. I say fiercer because in their case the incompetent or callous entity is also omniscient, omnipresent and omnipotent, which makes their world a very scary place. Especially since most theists believe in a deity which actively intervenes in their world from time to time.)

Perhaps we are part of a massive modelling exercise (a Monte Carlo simulation, perhaps) to determine the optimal way of achieving a specific goal. One candidate for that goal is the creation of superintelligence. From the perspective of a superintelligent alien species, individual humans might be about as interesting as dogs if we are lucky, or as microbes if not. Whereas a superintelligence might be seriously interesting. Maybe our simulators are in the business of creating new friends. Or maybe they need a lot of clever new colleagues to solve a really big problem, like the heat death of the universe.

Next week: the economical twist

Notes

(1) Bostrom’s trilemma makes a few assumptions, notably:

It is not impossible to create simulations inhabited by entities which consider themselves to be alive.

It is implausible that we are the most (or one of the most) technologically advanced civilisations that have ever existed in this universe.

It is implausible that we are one of the tiny, tiny minority of civilisations in this universe which arose naturally.

(2) The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy

October 23, 2016

The Hawking Recursion*

A couple of years ago Stephen Hawking told us that (general) AI is coming, and it will either be the best or the worst thing to happen to humanity. His comments owed a lot to Nick Bostrom’s seminal book “Superintelligence” and also to Professor Stuart Russell. They kicked off a series of remarks by the Three Wise Men (Hawking, Musk and Gates), which collectively did so much to alert thinking people everywhere to the dramatic progress of AI. They were important comments, and IMHO they were r

Journalists are busy people, good news is no news, and if it bleeds it leads. For a year or so the papers were full of pictures of the Terminator, and we had an epidemic of Droid Dread: the Great Robot Freak-Out of 2015.

The Terminator is an arresting image, and it’s good for getting people’s attention, but making people unreasonably scared of AI is unhelpful in the medium term. Among other things, it makes sensible AI resarchers cringe, and in turn they may under-state the risks inherent in AI. Or, like senior Googlers, it makes them go silent on the subject.

So when Professor Hawking repeated his remarks during the launch of the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence in Cambridge this week (October 2016), there was a need for balanced comment. Here is my contribution, in an interview with Sky News.

*If you’re wondering whether this title owes anything to The Big Bang Theory, you’re right.

October 16, 2016

Book review: “Homo Deus” by Yuval Harari, (part 3 of 3)

Week Three: Extreme Algocracy

In the first third of Homo Deus, Harari claims that humanity has more-or-less conquered its traditional enemies of famine, plague and war, and has moved on to chasing immortality, happiness and divinity. He also urged us all to become vegetarian, if only to make us less contemptible in the eyes of a future superintelligence.

In the second third of the book he offers a surprisingly cursory review of the two singularities – the economic and the technological. He seems to assume that most people already know about them, or at least won’t need much persuading to accept them.

Extreme algocracy

So finally we arrive at the main event, in which Harari predicts the dissolution of not only humanism, but of the whole notion of individual human beings. “The new technologies of the twenty-first century may thus reverse the humanist revolution, stripping humans of their authority, and empowering non-human algorithms instead … Once Google, Facebook and other algorithms become all-knowing oracles, they may well evolve into agents and finally into sovereigns.” As a consequence, “humans will no longer be autonomous entities directed by the stories their narrating self invents. Instead, they will be integral parts of a huge global network.” This seems to be an extreme version of an idea called algocracy, in which humans are governed by algorithms. The philosopher John Danaher is doing interesting work on this.

As an example of how extreme algocracy could come about, Harari asks you to “suppose my narrating self makes a New Year resolution to start a diet and go to the gym every day. A week later, when it is time to go to the gym, the experiencing self asks Cortana to turn on the TV and order pizza. What should Cortana do?” Harari thinks Cortana (or Siri, or whatever they are called then) will know us better than we do and will make wiser choices than we would in almost all circumstances. We will have no sensible option other than to hand over almost all decision-making to them.

Two new religions

Given his religious turn of mind, it is no surprise that Harari sees this extreme algocracy as leading to the birth of not one, but two new religions. “The most interesting place in the world from a religious perspective is not the Islamic State or the Bible Belt, but Silicon Valley.” Algocracy, he thinks, will generate two new “techno-religions … techno-humanism and data religion”, or “Dataism”.

“Techno-humanism agrees that Homo Sapiens as we know it has run its historical course and will no longer be relevant in the future, but concludes that we should therefore use technology in order to create Homo Deus – a much superior human model.” Harari thinks that techno-humanism is incoherent because if you can always improve yourself then you are no longer an independent agent: “Once people could design and redesign their will, we could no longer see it as the ultimate source of all meaning and authority. For no matter what our will says, we can always make it say something else.” “What”, he asks, “will happen to society, politics and daily life when non-conscious but highly intelligent algorithms know us better than we know ourselves?”

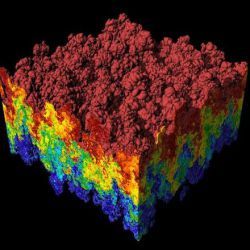

Dataism trumps Techno-humanism

“Hence a bolder techno-religion seeks to sever the humanist umbilical cord altogether. … The most interesting emerging religion is Dataism, which venerates neither gods nor man – it worships data. … According to Dataism, King Lear and the flu virus are just two patterns of data flow that can be analysed using the same basic concepts and tools. … Humans are merely tools for creating the Internet-of-All-Things, which may eventually spread out from planet Earth to cover the whole galaxy and even the whole universe. This cosmic data-processing system would be like God. It will be everywhere and will control everything, and humans are destined to merge into it.”

“Dataism isn’t limited to idle prophecies. Like every religion, it has its practical commandments. First and foremost, a Dataist ought to maximise data flow by connecting to more and more media, and producing and consuming more and more information.” So people who record every aspect of their lives on Facebook and Twitter are not clogging up the airwaves with junk after all; they are simply budding Dataists.

I am un-persuaded by the idea that mere data, undifferentiated by anything beyond quantity and complexity could become sovereign on this planet and throughout the universe. I think Harari has missed an interesting opportunity – if he replaced the notion of data with the notion of consciousness, I think he might be onto something important. It would not be the first time that a thinker proposed that mankind’s destiny (a religiously loaded word which he would perhaps approve) is to merge its individual minds into a single consciousness and spread it throughout the cosmos, but it might be the first time that a genuinely mainstream book did so.

In any case, Harari deserves great credit for staring directly at the massive transformations heading our way, and following his intuitions to their logical conclusions.

TL;DR:

A rather plodding first half may deter some fans of “Sapiens” (Harari’s previous book), but it is worth persevering for the extreme views about algocracy which he introduces in the final third.

October 9, 2016

Book review: “Homo Deus” by Yuval Harari, (part 2 of 3)

Week two: the two Singularities

In the first third of his new book, Yuval Harari described how humanity escaped its perennial evils of famine, plague and war, and he claimed that we are now striving for immortality, happiness and divinity. Now he enters the territory of the economic and the technological singularities. Read on…

Free will is an illusion

Harari begins this section by attacking our strong intuitive belief that we are all unitary, self-directing persons, possessing free will. “To the best of our scientific understanding, determinism and randomness have divided the entire cake between them, leaving not even a crumb for ‘freedom’. … The notion that you have a single self … is just another liberal myth, debunked by the latest scientific research.” This dismissal of personal identity (the “narrating self”) as a convenient fiction will play an important role in the final third of the book, which we will get to next week.

A curious characteristic of “Homo Deus” is that Harari assumes there is no need to persuade his readers of the enormous impact that new technologies will have in the coming decades. Futurists like Ray Kurzweil, Nick Bostrom, Martin Ford and others (including me) spend considerable effort getting people to comprehend and take into account the astonishing power of exponential growth. Harari assumes everyone is already on board, which is surprising in such a mainstream book. I hope he is right, but I doubt it.

Stop worrying and learn to love the autonomous kill-bot

Harari is also quite happy to swim against the consensus when exploring the impact of these technologies. A lot of ink is currently being spilled in an attempt to halt the progress of autonomous weapons. Harari considers it a waste: “Suppose two drones fight each other in the air. One drone cannot fire a shot without first receiving the go-ahead from a human operator in some bunker. The other drone is fully autonomous. Which do you think will prevail? … Even if you care more about justice than victory, you should probably opt to replace your soldiers and pilots with autonomous robots and drones. Human soldiers murder, rape and pillage, and even when they try to behave themselves, they all too often kill civilians by mistake.”

The economic singularity and superfluous people

As well as dismissing attempts to forestall AI-enabled weaponry, Harari has no truck with the Reverse Luddite Fallacy, the idea that because automation has not caused lasting unemployment in the past it will not do so in the future. “Robots and computers … may soon outperform humans in most tasks. … Some economists predict that sooner or later, un-enhanced humans will be completely useless. … The most important question in twenty-first-century economics may well be what to do with all the superfluous people.”

My income is OK, but what am I for?

Harari has interesting things to say about some of the dangers of technological unemployment. He is sanguine about the ability of the post-jobs world to provide adequate incomes to the “superfluous people”, but like many other writers, he asks where we will find meaning in a post-jobs world. “The technological bonanza will probably make it feasible to feed and support the useless masses even without any effort on their side. But what will keep them occupied and content? People must do something, or they will go crazy. What will they do all day? One solution might be offered by drugs and computer games. … Yet such a development would deal a mortal blow to the liberal belief in the sacredness of human life and of human experiences.”

Personally, I think he has got this the wrong way round. Introducing Universal Basic Income (or some similar scheme to provide a good standard of living to the unemployable) will probably prove to be a significant challenge. Persuading the super-rich (whether they be humans or algorithms) to provide the rest of us with a comfortable income will, I hope, be possible, but it may have to be done globally and within a very short time-frame. If we do manage this transition smoothly, I suspect the great majority of people will quickly find worthwhile and enjoyable things to do with their new-found leisure. Rather like many pensioners do today, and aristocrats have done for centuries.

The Gods and the Useless

I have more common ground with Harari when he argues that inequality of wealth and income may become so severe that it leads to “speciation” – the division of the species into completely separate groups, whose vital interests may start to diverge. “As algorithms push humans out of the job market, wealth might become concentrated in the hands of the tiny elite that owns the all-powerful algorithms, creating unprecedented social inequality.”

Pursuing this idea, he coins the rather brutal phrase “the Gods and the Useless”. He points out that in the past, the products of technological advances have disseminated rapidly through economies and societies, but he thinks this may change. In the vital area of medical science, for instance, we are moving from an era when the goal was to bring as many people as possible up to a common standard of “normal health”, to a world in which the cognitive and physical performance of certain individuals may be raised to new and extraordinary heights. This could have dangerous consequences: when tribes of humans with different levels of capability have collided it has rarely gone well for the less powerful group.

The technological singularity

The technological singularity pops up briefly, and again Harari sees no need to expend much effort persuading his mainstream audience that this startling idea is plausible. “Some experts and thinkers, such as Nick Bostrom, warn that humankind is unlikely to suffer this degradation, because once artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, it might simply exterminate humankind.”

October 3, 2016

Book review: “Homo Deus” by Yuval Harari

Week One: ending famine, plague and war…

Clear and direct

Yuval Harari’s book “Sapiens” was a richly deserved success. Full of intriguing ideas which were often both original and convincing, its prose style is clear and direct – a pleasure to read.*

His latest book, “Homo Deus” shares these characteristics, but personally, I found the first half dragged a little, and some of the arguments and assumptions left me unconvinced. I’m glad that I persevered, however: towards the end he produces a fascinating and important suggestion about the impact of AI on future humans.

Because Harari’s writing is so crisp, you can review it largely in his own words.

And because this review is long (over 2,000 words), I’m serialising it. If you’re impatient, you can get the whole thing now by signing up for my bi-monthly(ish) emails – just hit the “Free Short Story” link to your left.

From famine, plague and war to immortality, happiness and divinity

Harari opens the book with the claim that for most of our history, homo sapiens has been preoccupied by the three great evils of famine, plague and war. These have now essentially been brought under control, and because “success breeds ambition… humanity’s next targets are likely to be immortality, happiness and divinity.” In the coming decades, Harari says, we will re-engineer humans with biology, cyborg technology and AI.

The effects will be profound: “Once technology enables us to re-engineer human minds, Homo Sapiens will disappear, human history will come to an end, and a completely new kind of process will begin, which people like you and me cannot comprehend. Many scholars try to predict how the world will look in the year 2100 or 2200. This is a waste of time.”

There is, he adds, “no need to panic, though. At least not immediately. Upgrading Sapiens will be a gradual historical process rather than a Hollywood apocalypse.”

Vegetarianism and religion

At this point Harari indulges in a lengthy argument that we should all become vegetarians, asking “is Homo sapiens a superior life form, or just the local bully?” and concluding with the unconvincing (to me) warning that if “you want to know how super-intelligent cyborgs might treat ordinary flesh-and-blood humans [you should] start by investigating how humans treat their less intelligent animal cousins.” He doesn’t explain why super-intelligent beings would follow the same logic – or lack of logic – as us.

I also find myself uncomfortable with some of his linguistic choices, and two in particular. First, his claim that “now humankind is poised to replace natural selection with intelligent design,” seems to me to pollute an important idea by associating it with a thoroughly discredited term.

Secondly, he is (to my mind) overly keen to attach the label “religion” to pretty much any system for organising people, including humanism, liberalism, communism and so on. For instance, “it may not be wrong to call the belief in economic growth a religion, because it now purports to solve many if not most of our ethical dilemmas.” To many people, a religion with no god is an oxymoron. This habit of seeing most human activity as religious might be explained by the fact that Harari lives in Israel, a country where religious fervour infuses everyday life like smog infuses an industrialising city.

Science escapes being labelled as religion, but Harari has a curious way of thinking about it too: “Neither science nor religion cares that much about the truth, … Science is interested above all in power. It aims to acquire the power to cure diseases, fight wars and produce food.”

Humanism

A longish section of the book is given over to exploring humanism, which Harari sees as a religion that supplanted Christianity in the West. “Due to [its] emphasis on liberty, the orthodox branch of humanism is known as ‘liberal humanism’ or simply as ‘liberalism’. … During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as humanism gained increasing social credibility and political power, it sprouted two very different offshoots: socialist humanism, which encompassed a plethora of socialist and communist movements, and evolutionary humanism, whose most famous advocates were the Nazis.”

Having unburdened himself of all this vegetarianism and religious flavouring, Harari spends the second part of “Homo Deus” considering the future of our species, and on this terrain he recovers the nimble sure-footedness which made “Sapiens” such a great book.

Next week: Harari and the two singularities

*Sapiens does have its critics, including the philosopher John Danaher, who thinks it over-rated.

September 26, 2016

Guardian article: Our job now is to consider a future without work

September 18, 2016

The Reverse Luddite Fallacy

Economists can be surprsingly dangerous

Most economists are convinced that automation will not lead to lasting unemployment. They point out – rightly – that it has not happened in the past. Instead, it has made products and services cheaper, which raises demand and creates new jobs. They say that the Luddites, who went round smashing weaving machines in the early nineteenth century, simply mis-understood what was happening, and this mis-understanding has become known as the Luddite Fallacy.

But in the coming decades, automation may have a very different effect. Past rounds of automation replaced human and animal muscle power. That was fine for the humans who were displaced, as they could go on to do jobs which were often more interesting and less dangerous, using their cognitive faculties instead of their muscle power.

But in the coming decades, automation may have a very different effect. Past rounds of automation replaced human and animal muscle power. That was fine for the humans who were displaced, as they could go on to do jobs which were often more interesting and less dangerous, using their cognitive faculties instead of their muscle power.

It didn’t work out so well for the horse, which only had muscle power to offer. In 1900 there were around 25 million working horses on farms in America; now there are none. 1900 was “peak horse” in the American workplace. Are we heading towards “peak human” in the workplace?

Intelligent machines are replicating and in many cases improving on our cognitive abilities. What most of us do at work these days is to ingest information, process it, and pass it on to someone else. Intelligent machines are getting better at all of this than us. They are already better than us at image recognition; they are overtaking us in speech recognition, and they are catching up in natural language processing. Unlike us, they are improving fast: thanks to Moore’s Law (which is morphing, not dying) they get twice as good every eighteen months or so.

Self-driving cars are the obvious example: there are news stories every day about the plans of the tech giants and the big car makers, and Uber is running a live experiment with self-driving taxis in Pittsburgh.

Self-driving cars are just the start. The early stages of automation by intelligent machines are apparent in the legal, medical and journalist professions, and it is clear that it will affect every industry and every type of work. Retired British politicians like William Hague and Kenneth Baker (former foreign secretary and education secretary respectively) have begun to speak out about this, perhaps because they have nothing to lose and can afford to say the un-sayable.

No-one knows for sure how automation by intelligent machines will pan out. Maybe we will evolve an economy of what Silicon Valley types call “radical abundance”, where machines do all the boring jobs and humans concentrate on having fun.

Or maybe a more dystopian outcome will happen instead, with millions starving while the super-rich cower behind high walls and powerful AI-based defence systems.

Technological unemployment is not impossible. It is complacent and irresponsible to say that it is, based on no evidence beyond what has happened in the past. We should be discussing it and working out how to handle it if it does happen. Failure to do so is the Reverse Luddite Fallacy*, and it could be extremely dangerous for all of us.

* Hat-tip to the merry men behind The Singularity Bros podcast who, as far as I know, minted this phrase.