Calum Chace's Blog, page 17

January 4, 2016

Mark Zuckerberg’s New Year Resolution

Mark Zuckerberg’s New Year Resolution was to programme an AI to become his butler. He was aiming at Iron Man’s faithful companion, Jarvis. But surely he knows that Robert Downey Junior based his portrayal of Iron Man on Elon Musk?

Interview with BBC Radio 5 Live.

January 1, 2016

A dozen AI-related forecasts for 2016

An AI system devised by DeepMind will beat the best human at Go. (Rather splendidly, he is called Yoda.)

An AI system devised by DeepMind will beat the best human at Go. (Rather splendidly, he is called Yoda.)SwiftKey’s Neural Alpha – a keyboard for phones which uses Deep Learning to dramatically improve predictive typing – will be launched to the general public and will be big news.

Virtual reality will become really quite a big thing.

The existential risk organisations (FLI in Boston, FHI at Oxford, CSER at Cambridge, MIRI in California) will continue to grow resources and awareness despite a media backlash against 2015’s excitement about all things AI.

My book The Economic Singularity, about technological unemployment, will be published.

The debate about Universal Basic Income (UBI) will go mainstream, and become politicised. The left will demand it immediately, but no country will introduce it nationwide.

Siri, Cortana etc will get much better. But we won’t settle on a generic name for them yet.

Google Glass will make a comeback, ducking the “glasshole” cynicism by targeting B2B applications.

Google will announce a significant development with their collection of robot companies.

Intel will decide whether or not it is able to keep Moore‘s Law going in the next decade. If it can’t, IBM, Samsung and others will claim that they can.

The number of items considered part of the burgeoning Internet of Things will reach seventy bazillion.

California will reverse its decision to impose bureaucratic roadblocks to self-driving cars. Buses and trains without human drivers or chaperones will appear in a few more towns and cities around the world, and more new passenger cars will contain self-driving elements.

Happy New Year!

December 30, 2015

Eight big (AI) announcements in 2015

1. The Oxford Martin Programme on Technology and Employment

1. The Oxford Martin Programme on Technology and Employment

In January, Citibank helped establish this programme, to be led by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, authors of a famous paper on AI-driven automation. The programme is monitoring changes in the labour market, and watching for signs of irreversible technological unemployment.

2. Google open-sources Tensor Flow

In September, Google announced an important change in strategy. Having built a very lucrative online advertising business based on algorithms and hardware which produced better AI than anyone else, it was open sourcing its current best AI software – a deep learning engine called Tensor Flow. It only licenses the software for single machines, so even very well resourced organisations won’t be able to replicate the functionality that Google generates, but the move was significant.

The following month, Facebook announced that it would follow suit by open sourcing the designs for Big Sur, the server which runs the company’s latest AI algorithms.

3. Google announces RankBrain

In October, Google confirmed that it had added a new technique called RankBrain to its Search offering. RankBrain is a machine learning technique, and it was already the third-most important component of the overall Search service. It is applied to the 15% of searches which comprise words or phrases that have not been encountered before, and converts the language into mathematical entities called vectors, which computers can analyse directly.

4. SwiftKey announces Neural Alpha

In October, British AI company announced the launch of Neural Alpha, the first application of the AI technique of deep learning to mobile phone keyboards.

SwiftKey pioneered keyboards with a three-word suggestion bar above the keys that could accurately predict your next word. This was powered by a technology called “n-gram”, an approach now used on more than a billion devices globally. Where N-gram technology predicts words that have been seen before in the same sequence, Neural Alpha’s intelligent understanding of context introduces a more ‘human’ touch for mobile typing.

5. The Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence

In December, the Leverhulme Trust announced a grant of £10m to the Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risks (CSER). The centre will become an important new interdisciplinary research organisation, exploring the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence, both short and long term.

Dr Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh, CSER’s Executive Director, said that the Centre will look “at themes such as different kinds of intelligence, the responsible development of technology, and issues surrounding autonomous weapons and drones.”

6. Open A.I.

In December, a group of Silicon Valley luminaries including Elon Musk launched Open A.I., a non-profit artificial intelligence research company with $1 billion in initial funding. Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX, was joined by Y-Combinator president Sam Altman as a co-chair of the new organization. LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman, investor Peter Thiel, Amazon Web Services and Infosys are the other backers.

“It’s hard to fathom how much human-level AI could benefit society, and it’s equally hard to imagine how much it could damage society if built or used incorrectly,” the launch press release said.

7. Google’s quantum computer success

In December, Google announced that its D-Wave quantum computer was 100 million times faster than a traditional desktop computer in a “carefully crafted proof-of-concept problem”, as Google engineering director Hartmut Neven described it. Google acquired the machine in 2013, but had not previously been able to demonstrate its superiority.

Quantum computers use quantum bits (qubits) instead of the binary bits used in classical computers. These qubits can exist in a ‘superposition’ of either 0 or 1 simultaneously, allowing them to carry out a number of different calculations at once.

8. Baidu claims its speech recognition achieves human performance

December 2015, Baidu (often described as China’s Google) announced that its speech recognition system Deep Speech 2 performed better than humans with short phrases out of context. It uses deep learning techniques to recognise Mandarin.

December 24, 2015

Christmas Number One

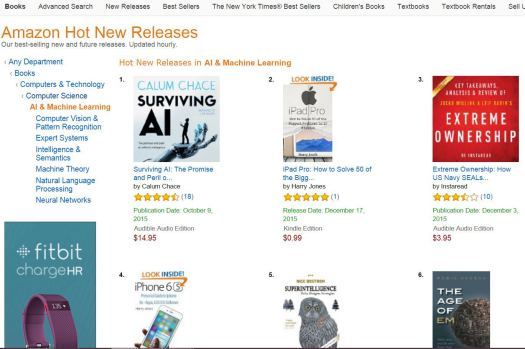

Sorry, but I couldn’t resist sharing this. “Surviving AI” is the Christmas Number One.*

A very Merry Christmas to you, and a Happy New Year!

* On Amazon’s top 100 new releases in AI and Machine Learning. (On Christmas Eve, anyway.)

December 3, 2015

Funding for dedicated organisation to study AI opportunity and risk

It’s great news that the Leverhulme Trust is granting £10m to Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risks (CSER). The money will fund an important new interdisciplinary research centre, the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, to explore the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence, both short and long term.

It’s great news that the Leverhulme Trust is granting £10m to Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risks (CSER). The money will fund an important new interdisciplinary research centre, the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, to explore the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence, both short and long term.

Dr Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh. CSER’s Executive Director, says that the Centre will look “at themes such as different kinds of intelligence, responsible development of technology, and issues surrounding autonomous weapons and drones.”

Prominent figures associated with CSER include professor Stuart Russell, a world-leading AI researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and professor Stephen Hawking, who famously said that if and when artificial general intelligence does arrive, “it’s likely to be either the best or worst thing ever to happen to humanity.” So no pressure, then.

It is interesting that this funding should come from the trust founded by a brilliant entrepreneur and philanthropist, William Lever, who created a lucrative global business from soap – a business which helped create the consumer goods giant Unilever. Lever established a model town for his employees at Port Sunlight, in Cheshire, because he wanted to provide the sort of decent living standards which were rare among industrial workers at the time. Today, the Leverhulme Trust provides £80m a year in research funding to the UK.

It is interesting that this funding should come from the trust founded by a brilliant entrepreneur and philanthropist, William Lever, who created a lucrative global business from soap – a business which helped create the consumer goods giant Unilever. Lever established a model town for his employees at Port Sunlight, in Cheshire, because he wanted to provide the sort of decent living standards which were rare among industrial workers at the time. Today, the Leverhulme Trust provides £80m a year in research funding to the UK.

But like many people of good will in those days, Lever was a deeply paternalistic man, and his commercial activities in the Congo, where he sourced palm oil, caused great suffering. This provides an interesting metaphor for the future of AI. Our actions are so heavily affected by the morality of our time: how well we understand the world around us, and how well we can predict the impacts of our progress. The next decades of AI research will generate great good, but we also need to avoid the potential for considerable harm.

November 24, 2015

Discussion of the Economic Singularity, Fondacion BankInter, Madrid

Fondaction BankInter is a leading global think tank based in Madrid. In 2015 it investigated the idea that machine intelligence may lead to technological unemployment. A workshop in June lead to a report which was published in November, and the Fondacion asked me and Juan Francisco Blanes, a roboticist, to give talks at the launch.

Fondaction BankInter is a leading global think tank based in Madrid. In 2015 it investigated the idea that machine intelligence may lead to technological unemployment. A workshop in June lead to a report which was published in November, and the Fondacion asked me and Juan Francisco Blanes, a roboticist, to give talks at the launch.

The volume on the video is very low, so earphones are required. And with splendid irony, my computer crashed during the presentation, so fans of schadenfreude will particularly enjoy the section at 23 minutes 37 seconds. Fortunately, the Fondacion staff came to the rescue with great efficiency and aplomb, and the talk re-starts at 28 minutes 27 seconds.

November 16, 2015

BBC History

November 14, 2015

FiveBooks

The excellent FiveBooks site interviewed me recently, and asked me to recommend five books to read about artificial intelligence. I think this is the century of two singularities, so I chose two books about the Technological Singularity (one each by Kurzweil and Bostrom) and two about what I call the Economic Singularity, the consequences of technological unemployment (one by Martin Ford and the other by McAfee and Brynjolfsson).

The interview (here), by Sophie Roell, is quite long, but a jolly good read (in my wholly un-biased opinion).

My fifth book choice is Permutation City by my favourite science fiction writer, Greg Egan. I don’t know anyone else who deals with the implications of strong AI better than Egan.

November 8, 2015

Homo sapiens may split in two: a handful of gods, and the rest of us

Charles Arthur, a journalist who writes for The Guardian and other outlets, wrote this intriguing article about the possibility of technological unemployment, and its potential impact on society:

Charles Arthur, a journalist who writes for The Guardian and other outlets, wrote this intriguing article about the possibility of technological unemployment, and its potential impact on society:

If you wanted relief from stories about tyre factories and steel plants closing, you could try relaxing with a new 300-page report from Bank of America Merrill Lynch which looks at the likely effects of a robot revolution.

If you wanted relief from stories about tyre factories and steel plants closing, you could try relaxing with a new 300-page report from Bank of America Merrill Lynch which looks at the likely effects of a robot revolution.

But you might not end up reassured. Though it promises robot carers for an ageing population, it also forecasts huge numbers of jobs being wiped out: up to 35% of all workers in the UK and 47% of those in the US, including white-collar jobs, seeing their livelihoods taken away by machines.

But you might not end up reassured. Though it promises robot carers for an ageing population, it also forecasts huge numbers of jobs being wiped out: up to 35% of all workers in the UK and 47% of those in the US, including white-collar jobs, seeing their livelihoods taken away by machines.

Haven’t we heard all this before, though? From the Luddites of the 19th century to print unions protesting in the 1980s about computers, there have always been people fearful about the march of mechanisation. And yet we keep on creating new job categories.

However, there are still concerns that the combination of artificial intelligence (AI) – which is able to make logical inferences about its surroundings and experience – married to ever-improving robotics, will wipe away entire swaths of work and radically reshape society.

“The poster child for automation is agriculture,” says Calum Chace, author of Surviving AI and the novel Pandora’s Brain. “In 1900, 40% of the US labour force worked in agriculture. By 1960, the figure was a few per cent. And yet people had jobs; the nature of the jobs had changed.

“The poster child for automation is agriculture,” says Calum Chace, author of Surviving AI and the novel Pandora’s Brain. “In 1900, 40% of the US labour force worked in agriculture. By 1960, the figure was a few per cent. And yet people had jobs; the nature of the jobs had changed.

“But then again, there were 21 million horses in the US in 1900. By 1960, there were just three million. The difference was that humans have cognitive skills – we could learn to do new things. But that might not always be the case as machines get smarter and smarter.”

“But then again, there were 21 million horses in the US in 1900. By 1960, there were just three million. The difference was that humans have cognitive skills – we could learn to do new things. But that might not always be the case as machines get smarter and smarter.”

What if we’re the horses to AI’s humans? To those who don’t watch the industry closely, it’s hard to see how quickly the combination of robotics and artificial intelligence is advancing. Last week a team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology released a video showing a tiny drone flying through a lightly forested area at 30mph, avoiding the trees – all without a pilot, using only its onboard processors. Of course it can outrun a human-piloted one.

MIT has also built a “robot cheetah” which can jump over obstacles of up to 40cm without help. Add to that the standard progress of computing, where processing power doubles roughly every 18 months (or, equally, prices for capability halve), and you can see why people like Chace are getting worried.

But the incursion of AI into our daily life won’t begin with robot cheetahs. In fact, it began long ago; the edge is thin, but the wedge is long. Cooking systems with vision processors can decide whether burgers are properly cooked. Restaurants can give customers access to tablets with the menu and let people choose without needing service staff.

Lawyers who used to slog through giant files for the “discovery” phase of a trial can turn it over to a computer. An “intelligent assistant” called Amy will, via email, set up meetings autonomously. Google announced last week that you can get Gmail to write appropriate responses to incoming emails. (You still have to act on your responses, of course.)

Further afield, Foxconn, the Taiwanese company which assembles devices for Apple and others,aims to replace much of its workforce with automated systems. The AP news agency gets news stories written automatically about sports and business by a system developed by Automated Insights. The longer you look, the more you find computers displacing simple work. And the harder it becomes to find jobs for everyone.

So how much impact will robotics and AI have on jobs, and on society? Carl Benedikt Frey, who with Michael Osborne in 2013 published the seminal paper The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation? – on which the BoA report draws heavily – says that he doesn’t like to be labelled a “doomsday predictor”.

He points out that even while some jobs are replaced, new ones spring up that focus more on services and interaction with and between people. “The fastest-growing occupations in the past five years are all related to services,” he tells The Observer. “The two biggest are Zumba instructor and personal trainer.”

Frey observes that technology is leading to a rarification of leading-edge employment, where fewer and fewer people have the necessary skills to work in the front line of its advances. “In the 1980s, 8.2% of the US workforce were employed in new technologies introduced in that decade,” he notes. “By the 1990s, it was 4.2%. For the 2000s, our estimate is that it’s just 0.5%. That tells me that, on the one hand, the potential for automation is expanding – but also that technology doesn’t create that many new jobs now compared to the past.”

This worries Chace. “There will be people who own the AI, and therefore own everything else,” he says. “Which means homo sapiens may be split into a handful of ‘gods’, and then the rest of us.

This worries Chace. “There will be people who own the AI, and therefore own everything else,” he says. “Which means homo sapiens may be split into a handful of ‘gods’, and then the rest of us.

“I think our best hope going forward is figuring out how to live in an economy of radical abundance, where machines do all the work, and we basically play.”

Arguably, we might be part of the way there already; is a dance fitness programme like Zumba anything more than adult play? But, as Chace says, a workless lifestyle also means “you have to think about a universal income” – a basic, unconditional level of state support.

Arguably, we might be part of the way there already; is a dance fitness programme like Zumba anything more than adult play? But, as Chace says, a workless lifestyle also means “you have to think about a universal income” – a basic, unconditional level of state support.

Perhaps the biggest problem is that there has been so little examination of the social effects of AI. Frey and Osborne are contributing to Oxford University’s programme on the future impacts of technology; at Cambridge, Observer columnist John Naughton and David Runciman are leading a project to map the social impacts of such change. But technology moves fast; it’s hard enough figuring out what happened in the past, let alone what the future will bring.

But some jobs probably won’t be vulnerable. Does Frey, now 31, think that he will still have a job in 20 years’ time? There’s a brief laugh. “Yes.” Academia, at least, looks safe for now – at least in the view of the academics.

October 12, 2015

Roll up, roll up! 50 FREE audio books!

Nice Mr Bezos has given me gift vouchers for 25 review copies of Pandora’s Brain audio books and 25 review copies of Surviving AI audio books.

Nice Mr Bezos has given me gift vouchers for 25 review copies of Pandora’s Brain audio books and 25 review copies of Surviving AI audio books.

You get a free book, and when you’ve listened to it, Amazon gets a review of the book – that’s the deal.

Gamification is everywhere these days, so these exciting freebies will be awarded for interesting / insightful / funny or even just plain honest completions of one of the two following statements:

“The best thing about AI is…”

or

“The scariest thing about AI is…”

Email your full name and your answer to calum@3cs.co.uk. Don’t forget to say which book you would prefer, and of course, first come, first served!