Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 275

March 4, 2014

Questionable: Romantic Conflict

Beth Matthews asked:

How do you come up with goals for your characters in a straight contemporary romance? . . . if there’s no suspense element, no capers. Can the romance itself be the goal? Or is it better to be an external goal? So, for example, in Bet Me is Min’s goal to have a date to her sisters wedding? Do the hero and heroine both need goals? Or do you pick one person to be the protagonist and focus on their goal to drive the story?

Conflict starts with conflicting goals, right? Well, I’m having trouble getting my building blocks in a row. Can people please talk about how they formulate conflict and goals in their contemporary romances? Pretty please?

I reformulated your question to ask about romantic conflict because I think that’s what you’re going after. That is, if a good conflict ends with one of the major characters (protagonist and antagonist) completely destroying each other, how can that be the start of a healthy relationship, since good relationships are based on compromise?

Let us all now turn to Moonstruck, possibly the most perfect romance ever filmed. Loretta is the protagonist. Ronny is the antagonist. Loretta wants a safe life with a man she doesn’t love. Ronny’s brother. Ronny wants a passionate life with the woman he adores, Loretta. The key here is that Loretta’s safe life is poisonous to her passionate nature, it imprisons her. So when Ronny, through the course of the plot, destroys Loretta’s life, she’s reborn into the woman she’s meant to be. (There’s that great image at the end of her coming out of the closet in her mother’s kitchen that’s a lovely rebirth image: Loretta in her ordinary clothes but with her hair tousled and her face flushed from making love all night with Ronny.)

Bet Me is going to haunt me forever in these discussions because that was, originally, magic realism. The antagonist was Fate, who takes an active role in the plot, pushing back. Min’s life is minimizing risk; Cal’s life is calculating risk; they’re both risk averse. But Fate (the Fairy Tale) has decided they must be together, so even though their goals are safe, uncomplicated lives, Fate keeps shoving them together. Fate defeats Cal first, because Cal’s plot is a subplot and you wind those up first. Then Fate defeats Min at the end, to such an extent that when everybody in her life who opposed the romance shows up, she deflects them without batting an eye.

Bringing Up Baby has this plot, the madcap liberating the professor. His Girl Friday has this plot, Walter destroying Hildy’s supposedly perfect future so she’ll come back to the life she really loves. There are variations on that; in The Proposal, both lovers have goals that motivate them to fake the relationship only to fall in love in spite of themselves and then have to untangle all the lies they’ve collaborated on before they can get together.

The big thing to avoid in the straight romance (that is, not connected to another kind of plot like a mystery; you can have gay and lesbian straight romances) is the Big Misunderstanding, which is usually created because there’s no real reason for these two crazy kids not to get together. The Big Misunderstanding is almost always toxic unless it’s set up as a straw man: He says, “That woman you saw me with me last night was my sister,” and she says, “I figured it must be because I knew you would’t betray me.” That can work because people can see a Big Misunderstanding coming a mile away, so if one crops up and the lovers behave like people who love and trust each other, it’s a nice surprise.

Lani and I did the movie Hitch for PopD, and it was a great illustration of this. The main romance was godawful, full of stupid plot turns and a really stupid Big Misunderstanding at the end because there was no other reason for these two beautiful, smart, successful people not to be together. But the subplot was a perfect romance: a schlubby guy who falls for a beautiful heiress. There’s a moment when he’s walked her home, and he’s trying to get up the nerve to kiss her, and he leaves her at the door, and then part way down the walk, he just can’t stand it, so he takes out his inhaler and takes a hit on it, and then throws it away, marches masterfully up to the door, and kisses her passionately. It’s a wonderful moment, you’re just cheering for him. And then much later in the movie, she’s telling somebody else about it, and she says, “And he threw away his inhaler!” like it’s the most romantic thing she’d ever seen, and you want to cheer again because she understands him and loves him, too. It’s just wonderful, and it’s a subplot in one of the dumbest romances ever put on film. (Although the scenes between Kevin James and Will Smith are really funny.)

So the short answer is give them real barriers to overcome, make them struggle and change to be with each other, and your goals and conflict will be there.

Oh, and quick answers for your other questions:

Do the hero and heroine both need goals?

If they’re going to be the protagonist and antagonist, yes.

Or do you pick one person to be the protagonist and focus on their goal to drive the story?

You always pick one person to be the protagonist of the main plot and one person to be the antagonist. If the protagonist’s love interest isn’t the antagonist, it’s good to give him or her a plot because that helps set up character.

Conflict starts with conflicting goals, right?

Not necessarily. The goals can be completely unrelated and the pursuit of the goals be the generator of conflict. For example, Jane wants to sell her grandfather’s home to developers to pay for the operation he desperately needs. John wants to save the three-toed-tree-frog whose only habitat is Grandpa’s farm. Jane bears the frog no ill will, John doesn’t want Grandpa to die, but their goals put them at cross purposes to each other. (Apologies to everyone who is tired of hearing about the damn frog; I’ve been using that example for decades.)

Fiction Archeology 1: Character in You Again

So, You Again. I either resurrect this sucker this time or it’s going to be the first book I’ve ever given up on.

For the past several days, I’ve pulled every file, every document, every jpg I’ve ever had on this book since 2004 (yes, that would be ten years since I started it) and waded through the files. So far, 687 of the files were so corrupted I could open them. Another 236 were duplicates or fragments I skimmed and knew I wouldn’t use. And then there were the 314 jpgs that just didn’t work any longer. Yes, I trashed 1237 docs and jogs. There’s still plenty left to read through before another cull: I kept eighty-nine outline and note docs and 143 jpgs, and probably half of those will go before I’ve got this book focused. And that’s all before I start on the actual scene files:

The moral is, if you’re going to keep working on a book (and killing two laptops with Diet Coke so that you have to rescue great whacks of documents in a hurry), stop and cull before ten years go by and you’re looking at a nightmare.

So as I dig down through ten years of layers on this book, I have realized many things. One is that starting this book as a homage to Agatha Christie, my version of the people locked in a country house with a murderer, was a bad idea for two reasons. The first is that I always start with my protagonist, my romance heroine, who shows up in my head and starts talking. If I try to go into a book any other way, it sets me back weeks, if not months (or years, in this case); Faking It is another example of this. So in the past ten years, my heroine has been named Zelda, Esme, Emma, Roxy, and now Zelda again. She’s been a cookbook writer and a botanist. She’s been depressed, angry, flirtatious, sexually rapacious, detached, and dead. Hey, it’s been ten years. People change.

Meanwhile, her best friend has only had two personas, Beth, a very sweet woman who bored me to tears and Scylla who has a difficult relationship with reality. I’m keeping Scylla, she’s very much alive on the page for me. Plus Scylla gave me the character dynamic I needed for the heroine. The two women have been best friends all their lives, working partners since they were 17, and they’ve fallen into the assumptions that plague any set of two: they’ve defined themselves by their relationship to each other. That is, Scylla is the creative dreamer and Zelda is the practical anchor. They write books about food which, unless you’re on the Food Network, is no sure way to make a living, and they’re in early thirties, so the peripatetic life they’ve been leading is beginning to pall. What they need is something to blast them out of their assumptions, which is the first act of the book. Because of what happens in the first act, really from the first scene, the women’s characters arc in opposition to each other, Zelda becoming the imaginative one (she starts seeing ghosts, people think she’s crazy) and Scylla becomes the practical one (because Zelda’s losing it). I think the opposites arc ends at the crisis, and the last act is them both finding a middle ground, independent of each other. I like that arc and it’s alive in my head instead of just making sense on paper, so I’m good with that.

Weirdly, most of the supporting cast is solid in my head. Rose, Malcolm, Quentin, Mike, Ruby, Ruby’s boyfriend (who’s had so many names I’m just going to toss them all and start over), Mary (gotta change that, too many M names), Angela, Nora, Liam, Francis, Issy . . . All of those people have very clear characters, back stories, arcs, I know them all. Well, I should, I’ve been thinking about them off and on for ten freaking years. So the only one I don’t have is my heroine. Oh, and my hero. Yes, the two main characters in a romance, and I’m still a little shaky on them. His name started out as James. I thought that was too formal, so I changed it to Spencer, but Spencer turned out to be kind of a stuffed shirt, so I changed it to Sam, and Sam is just not going to work here. James was a lawyer, but that was kind of stuffy, too, so I made Sam a hostage negotiator, which was more useful in the book, but . . .

So this week, I’m going through all the actual story I’ve put on paper, culling all the duplicates, all the stuff I know isn’t going to work, and I’m prepared to jettison most of it. When I went back to rewrite Bet Me, I think I ended up with about four thousand words of the original; everything else went. The good thing is, I like a lot of what I have, just from skimming it, so I should be able to salvage more. I have almost 60,000 words on this book (I think; could be more), they’re just all over the place, probably because I’m fuzzy on those two vital ingredients in a romance, the heroine and hero.

Oh, and the other problem with making this my homage to Agatha Christie’s Golden Age country house mysteries is that I am not an Agatha Christie writer. But then on an impulse, I re-read a Georgette Heyer country house mystery and realized that’s who my inspiration was, which makes sense since Heyer inspired me to write romance. The Girls: always as work, even when you’re reading for pleasure.

And now I must go do some more archaeology and hope I find a heroine and hero buried in the debris.

March 3, 2014

“The Juror #6 Job” Plot Breakdown and Subsequently on Leverage: “The 12 Step Job”

And here’s “The Juror #6 Plot” Breakdown.

An underlying motif in this plot is the game of chess, a motif that Leverage references throughout its five-season run. This episode is more blatant than most of the other stories (but not all; Sterling plays their game in “The Queen’s Gambit Job”) because the mark plays chess while she tries to steal the verdict. The plot moves are chess moves, with each side taking a piece from the board until the end Nate shows Earnshaw, the mark, that he’s taken her king, the crystal chess piece from the board in her command center. Lovely use of motif.

Act One: Let’s Save a Widow

Parker, forced into jury duty because she doesn’t pay attention to people, spots that the fix is in because she always pays attention to her surroundings, particularly the tech in her surroundings (in case she wants to steal something from there later). She goes back to the team and asks for help, and after discounting her, Nate get grief from the team and sends Eliot out with her to find out the truth. The truth is that she’s right, an investor named Earnshaw is buying the company and is fixing the trial to protect the company’s CEO, Quint, and the company’s assets; both Earnshaw and Quint know that the pills the company makes are dangerous, and they don’t care. The team goes to work, supporting Parker as their inside woman, which of course is the problem: Parker is going to have to learn how to be a woman instead of a thief.

The Change of Plans: “Let’s Go Steal A Jury”

The team realizes that, as Nate says, they got into this job way too late and the best they can do is con Quint, the company owner, into a settlement. Then Hardison notices that Earnshaw has just run a credit check on Alice White. Parker says, “Who’s Alice White?” and the entire team says, “You are!” Parker says, “Whoa” and pulls back, still having a long way to go on the human thing. Eliot points out that Earnshaw’s going to buy the jury. Nate says, “Not if we steal it first.”

Act Two: “Conversation, Compliments, You’ll Do Fine”

Earnshaw’s bribed the jury foreman, so the team has to take him out. Nate walks into the conference room and says, “Who plays chess?” Eliot says, “I do.” Nate says, “Of course you do,” acknowledging that Eliot is a lot more than dumb muscle; he’s smart muscle who figures out his moves ahead of time. A chess game, as Nate explains it, has three stages. In the beginning, you want to talk control of the board and protect your king which is the weakest piece you have. Earnshaw’s king is Quint, but she’s already attacked the defense (the widow’s lawyer) and bribed a juror, something Nate describes as “a fast, aggressive opening gambit.” So as their defensive move, Nate tells Parker to get the jurors to trust her: “Conversation,compliments, you’ll do fine.” Parker tries, but it’s a disaster, and when Sophie tries to coach her by asking her to talk Eliot out of the apple he’s holding, it gets worse. But when they find out the foreman has been bribed, Nate says, “Make him go away, Parker,” and she’s fantastic, lifting valuables from members of the jury and planting them on him, then squirting mustard on him so that he’s revealed as a thief. Then she takes charge of getting everything back to everyone and gets herself elected as the new jury foreman, a position where she’ll have to connect to make the con work. Parker’s a lot like Sophie who’s a terrible actress unless she’s on the con; Parker can’t connect with people, but she loves the job, so now she’ll learn. And Nate has taken an important piece in Earnshaw’s attack.

The Point of No Return: “Let’s Go Steal A Settlement”

But then Earnshaw takes the widow’s lawyer. Nate says, “We take a pawn, Earnshaw takes a knight. Lucky for us, we have more than one.” The team sends a terrified Hardison in as a replacement to stall the trial until they can finish conning Quint into a settlement, something that Parker’s now helping with behind the scenes as not just the jury foreman, but the woman who helped everybody get their valuables back. Then Peggy, a woman on the jury, tells Parker a secret and Parker says, “Wait. That means we’re friends,” and smiles. She’s getting the hang of it. PROGRESS!

Act Three: “I Can’t Do This”

Hardison delays while Sophie cons Quint into making a settlement. But then Earnshaw takes a big chess piece: she buys the company Sophie has been using to tempt Quint into a settlement, blocking Sophie and symbolically taking the team’s queen. And Parker is panicking; this people stuff is just too hard.

The Crisis: “Let’s Go Steal A Court Case”

Nothing left to do now but win the trial, Nate tells Hardison, with Parker working her new found people skills to sway the verdict in the jury room. Nate congratulates Hardison on a great closing argument, and then points his glass at Parker on the screen, saying, “It’s all on her now.” Meanwhile, Earnshaw begins to notice that somebody is playing chess with her, but then dismisses it; nobody is as smart as she is.

Act Four: “It’s All On Her Now”

Parker connects with the jury; then Hardison works his magic with Earnshaw’s video feed while Parker leads the jury in lunch selection and a guilty verdict.

The Climax: Checkmate

Earnshaw is blindsided by the guilty verdict, and then Nate delivers the coup de gras: he hands her the crystal king from her own chessboard. Check and mate.

The Denouement/Resolution: “Alice Made A Friend”

Parker gets an invitation for coffee from Peggy, her first real friend, although the team has to remind her again that she’s Alice. “You made a friend, Parker,” Sophie tells her and Parker is pleased. HUGE progress for our little whack-job.

Community Status: “We Really Make Each Other Better.”

After “The Juror #6 Job,” comes “The 12-Step Job” (aired tenth).

“The 12 Step Job”

The Caper Plot: Take down a money manager who embezzled from a charity

The Community Plot: The elephant in the room all season has been Nate’s drinking. Fortunately, the latest job involves putting the mark into rehab with Sophie as his group therapist; Parker as group member Rose, a kleptomaniac; and Nate as group member Tom Baker, an alcoholic (Hardison does the cover stories and he’s a Whovian). Forty-eight hours later, Nate is in withdrawal, hallucinating Sterling taunting him to take a drink. He may think that the key word in “functioning alcoholic” is “functioning,” but this episode makes it clear that in his case, it’s “alcoholic.” Meanwhile, Parker is happily crusing on anti-depressants and wants to stay in rehab because she’s making progress, building on her success as Juror #6. Sophie tries to talk Nate into facing his problem, but at the end, even as a ridiculously cheerful Parker goes off with her arms around Eliot and Hardison, Nate’s parting words to Sophie are, “I’m ready for a drink.” A team leader who’s a drunk is never a good thing, but it’s especially bad if he’s planning split-second heists that the fate of the team depends on.

This episode also makes clear another part of the group dynamic: Hardison, Parker, and Eliot have bonded like siblings. Eliot still threatens Hardison, and Hardison still pranks Eliot, and they both think Parker is nuts, but they’re clearly in “Nobody hits my brother but me” mode. Yes, there’s a romance brewing between Hardison and Parker, but it’s just brewing; their real relationship is that partnership of trust they share with Eliot. Nate and Sophie may be screwed up, but the younger three are a community.

Community Status: “The Kids Are All Right, But Dad’s a Drunk.”

Coming up: The double-episode finale “The First David Job” and “The Second David Job.”

March 2, 2014

Leverage Sunday: The Juror # 6 Job, Integrating a Single Character Subplot

Leverage has five members in its community which is a problem if you want to arc your characters by showing how the events of their stories change them and make them grow. One solution is to skip the character arcs and just do action stories, but that leaves a story with characters who become boring because they always react the same way, always do the same thing, Trying to arc each team member in every episode is just as bad; it results in truncated, chaotic plots and not much growth. A third option, giving an episode over to a single team member, would be almost as bad because it would kill the focus on community that makes this show so strong. The Leverage writers went with a different solution: giving characters their own subplots at different times in the series, making sure those subplots are integrated completely into the main plot so the character growth stuff never stops the main con plot in its tracks. “The Juror #6 Job” is a great example of this use of subplot.

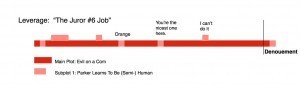

This is a diagram of the main con plot (red) and character subplot (pink).

The first minute of the plot sets up the reason for the con (a man died taking pills the manufacturer knew weren’t safe); the second minute of the plot sets up the character problem: Parker still isn’t a team player. She’s taking risks and endangering the rest of the team and she won’t listen when they tell her she’s hurting the work they do. Then she opens her mail and finds out that one of her aliases has jury duty, and Nate says she has to go. If she has to work with eleven other people, maybe she’ll learn something.

From then on, the plot and subplot merge because of course Parker finds out somebody’s rigging the jury and brings the team in on it. Now Parker has to connect to people in order to fulfill her part of the con. There are three places at roughly the turning points in the plot where Parker’s subplot gets its own scenes: when Sophie tries to train her to convince people to do things, at the midpoint when one of the jurors tells her she’s the nicest one there, and at the crisis point when she says “I can’t do this.” The rest of the plot focused on the twists and turns of the con, keeping the story moving. At the end, there’s two minutes of resolution, one minute for the con in general with some father/son bonding between Nate and Hardison, and one minute for Parker who has an invitation to lunch from “Alice’s friend.” Parker has made a small but significant leap in her character arc, and no main plots were harmed in the process. (Hardison also has a very small character arc in this as Nate has to throw him into the deep end to fake being the widow’s lawyer. He’s having a hard time, but when he apologizes to the widow, she tells him he’s the best lawyer she’s ever had, and then at the end Nate tells him he can do anything. Which Hardison of course snarks about, but still, small growth arc there for Hardison.)

And now the community. After nine episodes, the team is still evolving into family, but by now it’s a family that recognizes each other’s personality problems and is willing to point them out, in this episode, Parker’s selfish addiction to risk which happens in part because she doesn’t connect to the other people enough to see what she’s doing to them. Her detachment from people is shown in the way she speaks of Alice in the third person and continually has to be told by the others on the team that she’s Alice. But this is a family that also helps, so they all come together to coach Parker on how to be human, with Sophie taking the lead in the Mom role.

Parker’s success is shown when a person Parker meets on the jury sends her a note asking her to have coffee. Parker says, “Alice made a friend,” only to be told for the umpteenth time, “You’re Alice, you’ve made a friend,” and it finally sinks in: Parker has a friend. She’s still crazy, but if you look at who she is in this episode compared to who she was in the pilot, the change is clear, and it was done without Parker saying, “Hey, I feel different,” or the writers stopping the main plot for a Very Special Parker Moment: she made her friend and moved her character arc not just while she was working the team con, but because she was working the team con, as part of the team con.

Fun fact: The production hired Apollo Robbins to come in and train Beth Riesgraf to do lifts. She became so good at it that Robbins said she could probably do it as a living. Almost every lift Parker does in the series was really done by the actress.

Equally Fun Fact: Robbins plays Parker’s doppelgänger in “The 2 Live Crew Job,” so his character’s lifts are real, too.

The plot breakdown is coming later, probably tomorrow, because I let this slide. Very sorry. More tomorrow. Argh.

March 1, 2014

Cherry Saturday: Mar. 1, 2014

Today is National Pig Day. Show some respect and lay off the bacon for twenty-four hours, okay?

February 28, 2014

Managing Plot and Subplot

I watched three TV episodes this week about teams of good guys battling a mastermind who communicated with minions using ear coms. Two of them aired in the past week, the other is several years old, but the basic plot was the same: bring down the mastermind. The difference was in the way the stories used their subplots, and it was a big difference.

(Important Note: This is NOT a writing technique, it’s a critical approach. Don’t do this for your own stories, it’ll make you insane.)

“The Last Call” from Person of Interest.

The main plot is an extortion attempt on a 911 operator to get her to delete a 911 call that could convict someone of murder; the PoI team (Finch, Reese, and Shaw) work against the clock (it’s a time lock plot) to find first the child being held hostage and then the mastermind talking to the operator on her headset.

The first and only subplot is the team’s fourth member, Fusco, back on the job after his triumph in helping to bring down a huge police corruption ring, now being badgered by everybody who wants his opinion because he is The Man in the department. (If you’ve been watching this show from the pilot in which Fusco was a corrupt cop intending to execute Reese, you know how fantastic this subplot is. That’s character arc. Also, Fusco is the best.)

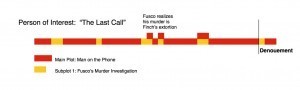

Here’s the plot/subplot breakdown (click to expand):

Each square represents one minute of screen time. In this case, The main plot starts at the beginning of the show with the kidnapping of a child, then there’s a cut to two minutes of Fusco being badgered by other detectives for help with their cases, including one newly promoted guy who asks for help on a murder. Then more main plot, followed by a minute of Fusco helping the rookie interview people in the murder, probably setting up his new partnership. (His last partner was the fifth member of the team, gunned down in the street last season; RIP Carter, we miss you.) Then back to the main case, with the son of a bitch on the phone blowing up a parking garage and threatening to do the kid next.

But when the plot goes back to Fusco’s subplot, the two stories connect, Finch asks Fusco for help, which he gives only to discover that his murder investigation is the crime the mastermind on the phone has been hired to cover up. (Note to writers: Don’t do this. A massive coincidence this late in the game is not good. PoI plots are usually much tighter than this.) So at this point, roughly the midpoint/point of no return, the two plots merge into one so that the subplot is no longer interrupting the main plot, it IS the main plot, which is the sole focus of the show until the kid is rescued. Then three minutes of denouement, one for Fusco back in the squad room with the rookie, and two for the mastermind to call Finch and tell him he’s gunning for him now.

The strength of this plot is its focus. There’s a time lock on a kidnapping, a child’s life at stake, so a lot of stuff about Fusco adjusting to life in the squad room without Carter would have killed the tension (Fusco does not chat about his feelings). Instead, Fusco is investigating a murder until halfway through when he’s part of the team again, and then it’s all main-plot-with-Fusco until the last two minutes.

And that’s another good thing about this plot; once the kid is rescued, it’s over. The writers gave the viewers three minutes of sigh space at the end (and in this show, a lot of the time you don’t even get that), one minute of Fusco back in the squad room and two minutes of resolution plus set up for a multi-arc antagonist. It’s tight, elegant plotting.

But some stories like emotional subplots, and that’s good, too. The next plot has a caper main plot and a character growth subplot, and still keeps the story tight.

“The Juror #6 Job” from Leverage.

The main plot is an attempt at jury-rigging by a criminally ambitious investor who is feeding the defense attorney instructions through an ear com and watching the trial through hidden cameras; the Leverage team (Nate, Sophie, Hardison, Eliot, and Parker) work first to get the company owner to settle and end the trial, and when the investor blocks that move, they work to steal the verdict.

The first and only subplot is trying to move team member Parker from “totally nuts” to “capable of faking sanity.”

Here’s the plot/subplot diagram:

The first minute shows a man dying from using an energy pill, setting up the litigation in the main plot. The next minute is the subplot, the team coming back from a job furious with Parker because she took risks not agreed on by the team. Just as they’re telling her she has to work well with people, she opens the mail sent to her alias, Alice White, and finds out she has jury duty. Nate, the leader, says she has to go because she has to learn to work with people, setting up the Parker-learning-to-fake-being-a-sane-person subplot.

But the joke’s on Nate because Parker spots the cameras and the ear cams and tells the team they have to do something or a widow is going to get swindled out of her case. For the rest of the episode, the Parker subplot is inextricably part of the main plot because her attempts to learn to connect with people are her job in the con. The plot only pulls out three one-minute scenes to focus on Parker’s growth curve: One scene in the first half where she fails miserably at convincing Eliot to trade his apple for her orange, one scene at the halfway point when another woman she’s been spending jury time with tells her a secret and then says, “You’re the nicest one here,” and one moment of despair at the crisis point when she says, “I can’t do this.” All three of those short scenes connect directly to the main plot because the success of the con depends on Parker being able to connect to everybody in the jury room. When they win the trial, the plot gives the viewer one minute of denouement for Hardison and the last minute for Parker, who opens her mail and gets an invitation to lunch from her buddy in the jury room; she’s connected. It’s a great example of integrating plot and subplot so that the viewer sees the entire story from the beginning as one plot.

And then there’s our last example.

“Time of Death” from Arrow

The main plot is about the Arrow team (Oliver, Diggle, Felicity, and Sara) taking on the Clock King, a computer expert trying to steal money for his sick sister.

The first subplot (listed in the order encountered) is about the tension in the Arrow cave as Felicity feels unneeded.

The second subplot is the island story which this week is about Sin, so it’s the island/Sin subplot.

The third subplot is the tension in the Queen family since Oliver severed connections with his mother without telling his sister.

The fourth subplot is the tension in the Lance family between Laurel and Sara, and between Quentin and Dinah, and between Quentin and Laurel . . .

(Note: These are not all the subplots in the series, just in this episode.)

If that list didn’t pinpoint the problem with this episode, look at the diagram:

The main action plot is the Clock King vs the Arrow Team. The first subplot integrates with that plot after the first act because a lot of the trauma that Felicity faces after that is because the Clock King invades the bat cave. If they’d stopped there, they’d have had an integrated plot and subplot like the plots we’ve already looked at. But this show wants to be more, so they’ve added three character dynamic subplots: one with backstory on the island to explain how Sara became a Big Sister to Sin, one dealing with the schism between Oliver and his mother, and one dealing with the ongoing cat fight that is the Lance family.

If I were writing this show, those last three subplots would be gone. Why? Because a forty-two minute story should devote the majority of its story real estate to the main plot. How much of that forty-two minutes was about the Clock King? Including the Arrow Cave subplot which merges with it, nineteen minutes or forty-five percent of it. Less than half. Another fifteen minutes or thirty-five percent were spent on the three family dynamic subplots. Where’s the last eight minutes? Denouement. Twenty percent of the story is spent after the climax.

There’s no way that distribution can deliver a focused story. The three relationship subplots have no bearing on the Clock King main plot and the Arrow Cave trauma subplot; if they weren’t in this story, the main plot would still make perfect sense. The thing Arrow does best is tell action stories; the best part of this episode was the riveting stuff with the Clock King and the excellent fight scenes. Even the annoying Felicity-feels-wounded subplot integrated beautifully with the main plot; it passed the test of a good subplot because the main plot would be less without it.

Imagine if the story had given those fifteen extra subplot minutes to that main plot, not to mention the extra seven minutes from the endless denouement (you’d still need the minute of Arrow cave denouement to finish the story). Or fine, you want a character subplot. PICK ONE. The island stuff bores me to tears, Sin is doing just fine in the story without any history, and if I never see the Lances have dinner again, it’s too soon, so I’d go with the Queens because I’d only have to give up four minutes to the entire subplot, I love watching Moira snarl, “This is my house,” and ohmygod at the end it’s Slade. And then I’d integrate the Queens’ drama-trauma into the main plot as some kind of complication so that it couldn’t be dropped from the plot without damaging the story.

Here’s the plot diagram with just the two subplots, Arrow cave and Queens:

That’s still less focused than the first two examples, but Arrow is kind of a messy show anyway, which is part of its charm. I’d give the Queens’ subplot one more minute, something that on a second viewing sets up what Moira is doing with Slade while complicating the main plot because I don’t think it’s a good idea to just drop a subplot for the back half of the story, but otherwise, even with the second subplot, that’s a pretty tight story.

Your main plot is the structure that holds the story together, the plot that all the subplots hang from. The more story real estate the main plot holds, the stronger your structure is and the more time you have to develop it, which means it can be richer in detail and event, reversal and escalation. Its subplots should have an effect on it: echo it, reverse it, complicate it, above all serve it. That kind of integration means that when you add your subplots, you’re not interrupting your main plot to tell a different story, you’re supporting that story, and that makes both the main plot and the subplots stronger.

Bottom line: If you take too much real estate away from your crunchy main plot, you’re diluting all that crunch, and that makes for soggy, confused storytelling.

Edited to add:

Here are the three plot diagrams together to help the comparison:

Questionable: Great Protagonists

Lola asked

What Makes a Great Protagonist?

A character you can’t stop reading about (or watching).

That’s really the only criteria. A protagonist can be anything, do anything, and as long as you can’t look away from him or her, the writer’s done a good job.

There’s a lot of stuff out there about how to make a protagonist likable, and a lot of it is good advice except that it implies that a protagonist has to be likable. Macbeth and Scarlett O’Hara would beg to differ. For “likable” substitute “fascinating” and you’re on the right track.

So what makes a protagonist fascinating? Depends on the reader/viewer. (Stop screaming. Nobody put a gun to your head and forced you to sign up for this gig. You volunteered.) I think it’s safe to say that a romance reader would probably not be interested in a married general who kills his king and then goes on a bloody rampage only to find his humanity again just as he faces the man whose family he slaughtered. I’m just guessing. Of course if the romance reader is somebody who also likes Elizabethan tragedy, then all bets are off.

But while I can’t give you a recipe for a universally fascinating protagonist, I can give you some fairly good guidelines.

1. He or she is vivid and alive on the page.

The protagonist is somebody we are willing to suspend disbelief for and invest in as if he or she was somebody real, somebody we know.

2. He or she in trouble in a way that we can understand.

If the protagonist is a mass murderer, the reader may have trouble connecting with his need to escape the law. But if the protagonist is a good man tempted by a prophecy and egged on by the woman he loves to fulfill it, and who then loses his grip, a reader can understand how he got into trouble and watch fascinated as he comes undone. If your protagonist isn’t doing anything truly awful, it’s even easier to establish sympathy: just give him or her undeserved trouble. Pretty much everybody has the same reaction to “That’s not fair.”

3. He or she has a goal we understand and sympathize with.

If the protagonist needs something that we understand needing, and we sympathize with his or her need to get it, we’ll sign on to root for success, especially if the stakes are high. That is, we can understand a protagonist wanting a hundred thousand dollars as a goal, but if that’s all, we’re not too invested. If we know he needs that hundred thousand to pay for medical care for his child, we understand the goal and sympathize with it. But if the child is dying, the stakes are high enough that we’re almost sure to be invested, as long as we believe in the protagonist. Stakes in a story are a triangulation of our understanding of the goal, what the goal means to the protagonist, and what the protagonist means to us.

4. He or she has an antagonist who is stronger and smarter.

A protagonist in trouble is in a static state; for us to stick throughout the story, the trouble has to get worse. And the best way to make trouble get worse is to bring in an antagonist in pursuit of a goal that brings him or her in direct conflict with the protagonist. That way each move the characters make increases the conflict for the other.

5. He or she fights the good fight.

The most fascinating protagonists get down in the dirt and fight hand to hand. They don’t hire people to do the dirty work, they don’t ask to be rescued, they get out there and, in their own ways, kick ass and take names. They may be terrible at fighting, they may get the hell kicked out of them, but they pick themselves up and go at it again because they will do anything to get their goals. And every time they get knocked down, they get up again smarter and stronger. Even if they lose in the end, we stick with them because we admire them for fighting so hard.

Of course you can have a great protagonist who doesn’t do any of these things. And you can have a protagonist who does all of these and just doesn’t work. There is no universal protagonist.

Good luck! (Yeah, I never said it would be easy.)

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

February 27, 2014

Arrow Thursday: So Many Things To Fix

When my students do formal critiques of a story, they hit four points:

Who’s the protagonist? What’s his goal?

Who’s the antagonist? What’s his goal?

What must be kept in this story [because it's so good]?

What must be fixed [in order for the story to work]?

So here’s my critique of the Arrow episode “Time of Death” followed by miscellaneous notes at the end. Warning: I really hated most of this, so you may just want to go play in the comments and ignore the post.

Who’s the protagonist? What’s his goal?

Oliver Queen. His goal is . . . uh, to stop the theft of a code-breaking device and some money and . . . uh, to throw a party for Sara? To tell off Laurel? He doesn’t have much focus or direction so it’s hard to tell.

Who’s the antagonist? What’s his goal?

The Clock King. His goal is to get money to save his sister. Although why he doesn’t just rob banks instead of stealing stuff he has to fence is beyond me. Still, great antagonist.

What Should Be Kept:

The Clock King: Great, smart antagonist set up as a doppelgänger for a member of the team. Huge possibilities there.

Diggle: Aside from the Scar Survey, still acting in character, smart, confident, strong, a much better leader than Oliver.

What Needs Work:

On-the-Nose Dialogue: “As you just said, Quentin, the guy who did this isn’t smart enough to have figured this out, so there must be somebody else behind it.” Or my favorite from the flashback: “Ivo killed Shado.” “Because I chose to save you.” Because they both didn’t already know that. Actually, just make that “Bad Dialogue” in general, especially that horrific scene in the bar where Laurel, in the grip of strong emotion, takes a metaphor and abuses it to the point of incoherence: “I was drowning because Oliver was my ‘ship and you sank it, and then I grabbed on to the anchor of alcohol and pills that dragged me down, but then a shark swam by, the shark of redemption, and I let that shark bring me here, water-logged and tooth-marked–I’d show you my scars but that would screw up the metaphor–and now here I am, covered in seaweed and shark spit, just a girl telling a sister that she loves her. Also I forgive you for being a skank.” Okay, that’s not what she said, but really, nobody in the grip of strong emotion uses an extended metaphor.

Cut This Scene: Too many scenes that don’t move the plot, any plot. I love Quentin, but we didn’t need a scene where his ex-wife tells him she’s not coming back; it’s there because his hope for a re-kindled marriage is what drives Laurel to throw the dinner party to which her sister, with an emotional tone-deafness that defies all logic (see Plot-Driven Character), brings Oliver, which causes the meltdown which sends Oliver to feel superior to Laurel and cut off their non-romance (see Unsympathetic Protagonist). Scenes like this take up real estate that could have been spent on the real story, which is the Arrow team vs the Clock King, and not all this emotional angst from people we just want to slap while we yell “Snap out of it!”

Contrived Problems: There is no reason for Oliver not to tell Thea the truth. There is no reason for Oliver not to tell Quentin he’s the Arrow. There is no reason for Oliver to go to the Lance family dinner. There is no reason for Felicity or the Clock King to be at the bank. Contrived Problems are story-killers because they lead to

Plot-Driven Characters (aka, “My character would be smarter than this but the writers need this scene to happen so I’m going to be an idiot here.”) In the case of this episode, pretty much everything everybody does.

Unsympathetic Protagonist. You know, they had a good character going in Oliver and they have just mutilated him. “I have loved you for half my life” except when I was doing your sister and helping you torpedo your relationship with the man who really loved you, and because my love is not real and unconditional I can now berate you for being cold to your sister while I’m lying to mine, and I’m also lying to you because your sister is lying to you about who she is but that’s okay because what we do is justified but what you do is not because . . . uh, I’m Oliver Queen.” You know what makes for a lousy hero? Lying, hypocritical, judgmental takedowns of the people the hero has injured and continues to injure.

Other notes:

Sure, Sara’s an equal because Diggle and Oliver would absolutely apologize to each other if one of them got hit. And then we get the Scar Survey Trope, done better in Lethal Weapon 3 and Leverage’s “The 2 Live Crew Job.” It’s okay to use a standard trope, you just have to use it better than it was done before. In both of those examples (and in most examples of this trope) it’s people showing off their scars as foreplay, but since there’s no Arrow cave three-way, the trope has no impact on any of the people in the conversation. Worse, it’s completely out of character because I will bet any amount of money that Oliver and Diggle who have been training together for a season and a half have never had this conversation on their own. So why are two taciturn men and a secretive blonde showing off their scars and acting completely out of character? Because the plot needs Felicity to feel left out, aka it’s Plot-Driven Character. Another problem: it makes them look like they’re bragging, trying to top each other in some kind for fourteen-year-old “Oh, yeah? Well, I mostly get shot” kind of competition. Also, why doesn’t anybody ever hit these people in the face? All those scars and yet still perfect complexions. Stupid use of a foreplay trope that damages character in the process and doesn’t move story.

This scene (the one where Felicity feels left out while the others compare scars) does not make Felicity look vulnerable, it makes her look like an idiot, right up there with “I love spending the night with you.” Rickard is a good actress, she could have done all of that with a look. And then there’s Sara: “You’re so cute.” Bite me, Sara. Don’t patronize people; you’re not a in a position of superiority here.

Oliver re Laurel: “She’ll come around.” So he’s an idiot. At least Sara has a grip on reality. You know, if he’s this bad at reading people, he’s not a Leader, he’s a Hitter. Diggle reads people. Is it too late to call this show Diggle?

Laurel’s “a little mad at Sara”? Oliver cannot possibly be that dumb. How can Sara leave her own party? She and Oliver just duck out and nobody notices? Why is this party even here? It doesn’t move plot in any way. Oliver and his mother are still at odds. The Lances are still happy Sara’s back. Why was this scene here? Cut This Scene.

“Wolziak (?) was just the muscle. We need to find the brain.” Y’know, I think Quentin already knew that since he just said, “Wolziak is small time on a good day. I doubt he’d even know how to use thing, let along break in and steal it on his own.” On-The-Nose Dialogue.

“Smaller people like us.” Finally, Sara shows some sensitivity, but Felicity’s tired of being patronized.

And we’re back on the island? Why? Edited to add: Oh, to set up Sin. Because that couldn’t have been done in a line of dialogue. Cut this Scene.

How much do I love Quentin? And Laurel, really happy because he thinks her mom might come back, so she offers dinner. Finally a Lance scene that isn’t toxic. Also, finally a scene that moves plot and doesn’t violate character.

The Clock King is a great antagonist. What a shame he’s been in this for about five seconds.

Love “He doesn’t know there’s two of us.” Great action stuff. Scenes move plot, don’t violate character. Go, Arrow.

Oliver patronizes Thea by not telling her the truth. She’s an adult. Kiss on the forehead. Oliver, I will buy you as the Hitter/Muscle in this show, but you couldn’t lead any of these people out of a paper bag. Where’s Diggle?

Sara knows blood analysis, computers, has perfect hair, can kick ass. That must have been some five years. Edited to add: And BARTEND. She makes a perfect drink. I’m thinking of a very old sexist joke that ends “And a flat head to put my pizza on.”

Clock King/sister; Oliver/sister; Sara/sister. Those parallels can’t be an accident, but they just left it there because they were squandering story real estate on scenes that went nowhere.

The Clock King is a great antagonist.

If Oliver liquidates 800,000 shares, doesn’t Isabel buy them? Wouldn’t Walter point that out? Wouldn’t the Clock King see the sudden appearance of all that money as suspicious? Why am I expecting this show to to make sense?

Are you kidding me? Sara wants Oliver to go with her because she doesn’t want to face Laurel alone? Because bringing Oliver will make things so much better? Now Sara’s an idiot, but she can’t help it, her character’s been taken hostage by the plot. Plot-driven character. And now, the show’s convinced me that Oliver and Felicity are a bad idea. I want Diggle and Felicity to run the Arrow cave. Sara can go live with her mother and tend bar for the Flash in Central City. And Oliver can shoot people with arrows when Diggle and Felicity tell him to.

I like it that Felicity is feeling threatened as a team member, not because of her crush on Oliver. That gives her a little of her self-respect back. But they’re still defining her in terms of Oliver and the Arrow cave. Speaking of the Arrow cave, where’s Roy? Did the writers get bored with his plot line? Because you know he’d be there.

I am so Team Laurel at this point, except she deserves better than Oliver.

And Laurel speaks for the entire viewing audience. Or at least me.

So Laurel tells Oliver the truth, and he deflects it by pointing out that she drinks. Oliver “You have no idea what’s going on with my family right now.” Because the fact that I just screwed up your family again is not as important as the fact that I’m lying to my sister. Self-involved, sanctimonious jerk.

“I have loved you for half my life but I’m done running after you.” WTF? When has he ever run after her on this show? He’s screwing her sister and NOW he’s telling her he’s done with her? She got that memo, Oliver, when her idiot sister dragged you to the dinner that was supposed to reunite their broken family and then exchanged long looks with you. I really don’t like Oliver, and not just in this moment. I haven’t liked him for several episodes and now it’s coalescing around this moment. He’s turning into the guy I want the hero to beat up. Diggle? Could you come in here and smack the shit out of Oliver? Thank you.

So is it smart that Felicity is in the bank or dumb? I really want her to be smart and not just going into danger to be a wannabe. The jacket is not a good touch, especially with Sara pointing it out. Tacky, Sara.

“Diggle get her out of here.” Because Diggle is just his driver now?

FINALLY, Diggle gets a real job. And he gets to defeat technology with brawn, which means his skill set is perfectly balanced by Felicity’s. In fact, Felicity and Diggle defeat the Clock King. And I am suddenly struck by how great a Felicity/Diggle team could be. Send Sara and Oliver back to the island, get Laurel a nice guy who appreciates her instead of screwing her over, and give this show to Diggle and Felicity.

Of course Felicity is better at computers than Sara. She had to have known that because she’s not stupid but hey, the plot needed her to feel threatened, so . . . Plot-Driven Character.

Very happy the Lance Catfight is over but this dialogue is just deadly. Nobody in the grip of sincere emotion talks in extended metaphors.

If Felicity saves everybody, why is she cowering while Sara stands triumphant? Do the writers think keeping their feet on her neck is characterization?

How did this show get so bad so fast? What happened?

Edited to Add: I left off the disclaimer I put the beginning of the Arrow posts because things were going so well. Then I got this comment from Dennis:

This is why no one respects women, they watch shows because “there’s hot topless men in it and they do stuff coz abs”. If you’re going to critique something, at least watch it properly, moron.

Yes, Dennis has issues. He also had a valid point in the first part of his comment which I can’t post without editing the insults out of his comment, and I don’t edit comments, so here’s the disclaimer again:

Community Rules: Treat everyone with courtesy and respect. Do not say somebody is wrong, say “I respectfully disagree.” Any comment that refers to anyone in a derogatory way is going to get trashed. Any comment in a sarcastic, snide, or demeaning tone will be trashed even faster. Any comment that says”this is why no one respects women” will be ignored because really? Really, Dennis?

February 26, 2014

Antagonists Again

The 12 Most Codependent Supervillains of All Time is an interesting look at protatonist/antagonist pairings that need each other to define themselves or because they’re the only people who can understand each other, including some doppelgängers. Don’t forget to look at the comments; lots of good suggestions there. With thanks to io9.

February 25, 2014

Questionable: Turning an Idea Into a Plot

Georgia wrote:

I’d like to know about how to turn an idea into a plot . . . At this point I sort of go “Okay, so what do you want?” and if the character doesn’t know the whole thing stalls. If they do know, I can randomly follow that thread (poke the sore spot and see what happens), but that approach doesn’t lend itself so well to a structured narrative. So I’m guessing that it starts with a goal, but building an actual plot beyond that leaves me completely bewildered…

Okay, THIS one I can answer.

There are any number of ways to turn an idea into a plot, but the big two are:

1) Discovery, also known as pantsing (as in “flying by the seat of your pants). In this method you just start writing and keep going until you have enough stuff on the page to see where the idea is going, usually at least thirty thousand words, many of which you’ll cut. Then you break down what you have by analyzing it according to the kind of structure you want (linear, patterned, epic, etc.).

2) Outlining, which means you take your idea and analyze it before you write. You figure out who your protagonist is, what he or she wants, and why he or she can’t get it. Then you figure out who your antagonist is (the person preventing the protagonist from getting the goal) and what he or she wants. You analyze the conflict (a conflict box comes in handy), try to tweak it so it’s a conflict lock (neither can escape from the conflict). And then you start writing.

Whichever way you start, at some point you have to look at the story overall to see if it’s a short story, a novella, a novel, whatever; what POV is going to best communicate the story; and how you’re going to structure everything. How much plot do you have? What are the turning points? Do the acts escalate? Do the turning points make the story new? Does your climax pay off the promise of the first scene? And ten million other structure and character details.

After that it’s lather, rinse, repeat. (Write, analyze, revise.)