Managing Plot and Subplot

I watched three TV episodes this week about teams of good guys battling a mastermind who communicated with minions using ear coms. Two of them aired in the past week, the other is several years old, but the basic plot was the same: bring down the mastermind. The difference was in the way the stories used their subplots, and it was a big difference.

(Important Note: This is NOT a writing technique, it’s a critical approach. Don’t do this for your own stories, it’ll make you insane.)

“The Last Call” from Person of Interest.

The main plot is an extortion attempt on a 911 operator to get her to delete a 911 call that could convict someone of murder; the PoI team (Finch, Reese, and Shaw) work against the clock (it’s a time lock plot) to find first the child being held hostage and then the mastermind talking to the operator on her headset.

The first and only subplot is the team’s fourth member, Fusco, back on the job after his triumph in helping to bring down a huge police corruption ring, now being badgered by everybody who wants his opinion because he is The Man in the department. (If you’ve been watching this show from the pilot in which Fusco was a corrupt cop intending to execute Reese, you know how fantastic this subplot is. That’s character arc. Also, Fusco is the best.)

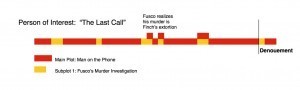

Here’s the plot/subplot breakdown (click to expand):

Each square represents one minute of screen time. In this case, The main plot starts at the beginning of the show with the kidnapping of a child, then there’s a cut to two minutes of Fusco being badgered by other detectives for help with their cases, including one newly promoted guy who asks for help on a murder. Then more main plot, followed by a minute of Fusco helping the rookie interview people in the murder, probably setting up his new partnership. (His last partner was the fifth member of the team, gunned down in the street last season; RIP Carter, we miss you.) Then back to the main case, with the son of a bitch on the phone blowing up a parking garage and threatening to do the kid next.

But when the plot goes back to Fusco’s subplot, the two stories connect, Finch asks Fusco for help, which he gives only to discover that his murder investigation is the crime the mastermind on the phone has been hired to cover up. (Note to writers: Don’t do this. A massive coincidence this late in the game is not good. PoI plots are usually much tighter than this.) So at this point, roughly the midpoint/point of no return, the two plots merge into one so that the subplot is no longer interrupting the main plot, it IS the main plot, which is the sole focus of the show until the kid is rescued. Then three minutes of denouement, one for Fusco back in the squad room with the rookie, and two for the mastermind to call Finch and tell him he’s gunning for him now.

The strength of this plot is its focus. There’s a time lock on a kidnapping, a child’s life at stake, so a lot of stuff about Fusco adjusting to life in the squad room without Carter would have killed the tension (Fusco does not chat about his feelings). Instead, Fusco is investigating a murder until halfway through when he’s part of the team again, and then it’s all main-plot-with-Fusco until the last two minutes.

And that’s another good thing about this plot; once the kid is rescued, it’s over. The writers gave the viewers three minutes of sigh space at the end (and in this show, a lot of the time you don’t even get that), one minute of Fusco back in the squad room and two minutes of resolution plus set up for a multi-arc antagonist. It’s tight, elegant plotting.

But some stories like emotional subplots, and that’s good, too. The next plot has a caper main plot and a character growth subplot, and still keeps the story tight.

“The Juror #6 Job” from Leverage.

The main plot is an attempt at jury-rigging by a criminally ambitious investor who is feeding the defense attorney instructions through an ear com and watching the trial through hidden cameras; the Leverage team (Nate, Sophie, Hardison, Eliot, and Parker) work first to get the company owner to settle and end the trial, and when the investor blocks that move, they work to steal the verdict.

The first and only subplot is trying to move team member Parker from “totally nuts” to “capable of faking sanity.”

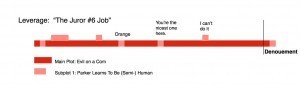

Here’s the plot/subplot diagram:

The first minute shows a man dying from using an energy pill, setting up the litigation in the main plot. The next minute is the subplot, the team coming back from a job furious with Parker because she took risks not agreed on by the team. Just as they’re telling her she has to work well with people, she opens the mail sent to her alias, Alice White, and finds out she has jury duty. Nate, the leader, says she has to go because she has to learn to work with people, setting up the Parker-learning-to-fake-being-a-sane-person subplot.

But the joke’s on Nate because Parker spots the cameras and the ear cams and tells the team they have to do something or a widow is going to get swindled out of her case. For the rest of the episode, the Parker subplot is inextricably part of the main plot because her attempts to learn to connect with people are her job in the con. The plot only pulls out three one-minute scenes to focus on Parker’s growth curve: One scene in the first half where she fails miserably at convincing Eliot to trade his apple for her orange, one scene at the halfway point when another woman she’s been spending jury time with tells her a secret and then says, “You’re the nicest one here,” and one moment of despair at the crisis point when she says, “I can’t do this.” All three of those short scenes connect directly to the main plot because the success of the con depends on Parker being able to connect to everybody in the jury room. When they win the trial, the plot gives the viewer one minute of denouement for Hardison and the last minute for Parker, who opens her mail and gets an invitation to lunch from her buddy in the jury room; she’s connected. It’s a great example of integrating plot and subplot so that the viewer sees the entire story from the beginning as one plot.

And then there’s our last example.

“Time of Death” from Arrow

The main plot is about the Arrow team (Oliver, Diggle, Felicity, and Sara) taking on the Clock King, a computer expert trying to steal money for his sick sister.

The first subplot (listed in the order encountered) is about the tension in the Arrow cave as Felicity feels unneeded.

The second subplot is the island story which this week is about Sin, so it’s the island/Sin subplot.

The third subplot is the tension in the Queen family since Oliver severed connections with his mother without telling his sister.

The fourth subplot is the tension in the Lance family between Laurel and Sara, and between Quentin and Dinah, and between Quentin and Laurel . . .

(Note: These are not all the subplots in the series, just in this episode.)

If that list didn’t pinpoint the problem with this episode, look at the diagram:

The main action plot is the Clock King vs the Arrow Team. The first subplot integrates with that plot after the first act because a lot of the trauma that Felicity faces after that is because the Clock King invades the bat cave. If they’d stopped there, they’d have had an integrated plot and subplot like the plots we’ve already looked at. But this show wants to be more, so they’ve added three character dynamic subplots: one with backstory on the island to explain how Sara became a Big Sister to Sin, one dealing with the schism between Oliver and his mother, and one dealing with the ongoing cat fight that is the Lance family.

If I were writing this show, those last three subplots would be gone. Why? Because a forty-two minute story should devote the majority of its story real estate to the main plot. How much of that forty-two minutes was about the Clock King? Including the Arrow Cave subplot which merges with it, nineteen minutes or forty-five percent of it. Less than half. Another fifteen minutes or thirty-five percent were spent on the three family dynamic subplots. Where’s the last eight minutes? Denouement. Twenty percent of the story is spent after the climax.

There’s no way that distribution can deliver a focused story. The three relationship subplots have no bearing on the Clock King main plot and the Arrow Cave trauma subplot; if they weren’t in this story, the main plot would still make perfect sense. The thing Arrow does best is tell action stories; the best part of this episode was the riveting stuff with the Clock King and the excellent fight scenes. Even the annoying Felicity-feels-wounded subplot integrated beautifully with the main plot; it passed the test of a good subplot because the main plot would be less without it.

Imagine if the story had given those fifteen extra subplot minutes to that main plot, not to mention the extra seven minutes from the endless denouement (you’d still need the minute of Arrow cave denouement to finish the story). Or fine, you want a character subplot. PICK ONE. The island stuff bores me to tears, Sin is doing just fine in the story without any history, and if I never see the Lances have dinner again, it’s too soon, so I’d go with the Queens because I’d only have to give up four minutes to the entire subplot, I love watching Moira snarl, “This is my house,” and ohmygod at the end it’s Slade. And then I’d integrate the Queens’ drama-trauma into the main plot as some kind of complication so that it couldn’t be dropped from the plot without damaging the story.

Here’s the plot diagram with just the two subplots, Arrow cave and Queens:

That’s still less focused than the first two examples, but Arrow is kind of a messy show anyway, which is part of its charm. I’d give the Queens’ subplot one more minute, something that on a second viewing sets up what Moira is doing with Slade while complicating the main plot because I don’t think it’s a good idea to just drop a subplot for the back half of the story, but otherwise, even with the second subplot, that’s a pretty tight story.

Your main plot is the structure that holds the story together, the plot that all the subplots hang from. The more story real estate the main plot holds, the stronger your structure is and the more time you have to develop it, which means it can be richer in detail and event, reversal and escalation. Its subplots should have an effect on it: echo it, reverse it, complicate it, above all serve it. That kind of integration means that when you add your subplots, you’re not interrupting your main plot to tell a different story, you’re supporting that story, and that makes both the main plot and the subplots stronger.

Bottom line: If you take too much real estate away from your crunchy main plot, you’re diluting all that crunch, and that makes for soggy, confused storytelling.

Edited to add:

Here are the three plot diagrams together to help the comparison:

newest »

newest »

Great post! I really enjoyed the breakdown and it even gave me some thinky thoughts on a pending novel length project. Managing the length has always been an issue, and this post had me thinking about length in a different way. Thanks, again!

Great post! I really enjoyed the breakdown and it even gave me some thinky thoughts on a pending novel length project. Managing the length has always been an issue, and this post had me thinking about length in a different way. Thanks, again!