Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 276

February 24, 2014

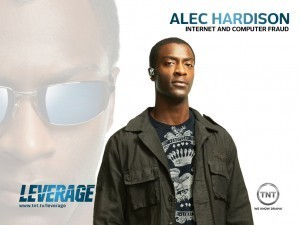

Subsequently on Leverage: The Community Arc Through Season One

Since this series of TV Sundays is about building a community, here’s a synopsis of the community building done over the first season of Leverage in the eight episodes that come between “The Nigerian Job” and “The Juror #6 Job” which is the episode for next Sunday

2. The Homecoming Job (aired second)

The Caper Plot: Get justice for a reservist shot by mercenaries in Afghanistan.

The Community Plot: The team reunites for their first job after taking down Victor. Nate’s given most of his payout to charity, but he’s taken part of it and set them up as a consulting firm with fancy offices and extensive back stories, and shortly after that Parker pushes Hardison off a building for his first cable leap (bonding!). But the job turns dangerous when it becomes obvious that the bad guys are willing to kill to keep their secret, and Sophie, Parker, and Hardison have second thoughts until Nate, with a bottle in his hand, says, “Hey, you called me. If you don’t want to do this, walk away.” “We finish this one,” Eliot says. “Just this one,” Parker says and they go back to work, Sophie taking the bottle away from Nate. Trouble ensues, but they beat the bad guys and save the Corporal while funding his rehab center, and at the end, when they’re all feeling pretty good, Nate says, “Anybody who wants to walk away can do it right now.” Eliot says,”One more job.” Hardison says, “Maybe two.” Parker says “I bought a plant [for my office].” Hardison says, “Nice. Team spirit.” And four of them walk away together while Nate drives off in his Tesla (the other thing he bought before he gave the rest to charity).

COMMUNITY STATUS: We’ll Do One More Job . . .

3. The Wedding Job (aired seventh)

The Caper Plot: Get a mob boss who pinned a murder on someone loyal to him and then didn’t take care of his family.

The Community Plot: Sophie brings in the man’s wife who wants justice, but Nate says no, it’s a mob thing. The rest of the team overrules him, and they scope out the situation. Nate tries to talk them out of the job one more time, and then gives in and they infiltrate the wedding of the mob boss’s daughter to steal the money the man’s wife is owed. The team’s not exactly a well-oiled machine, but nobody’s talking about walking away, and Hardison and Eliot stop fighting long enough for Hardison to tell Eliot he’s a good cook (chef school, no less) and for Eliot to tell Hardison he’d been in love once but she married somebody else. Hardison said, “What did you do?” Eliot says, “I liberated Croatia.” Hardison says, “I’d have just got fat.” Hey, it’s a kind of bonding. Also, Parker continues to dazzle Hardison, and Sophie wants Nate to tell her where they are in their relationship while Nate just wants to know where they are in the con. This episode also includes FBI agents Taggert and McSweeten and Nate’s classic line, “Did you just kill somebody with an appetizer?”

COMMUNITY STATUS: Our Communication Needs Work

4. The Snow Job (aired ninth)

The Caper Plot: Save a National Guardsman who was swindled by a contractor.

The Community Plot: Sophie, Eliot, Parker, and Hardison have settled into a working team, but Nate didn’t get the “we’re a community” memo; he’s making decisions without them and they’re not happy; they’re even unhappier because his drinking is out of control. In the end, Nate leads them to another victory, but the stress on the team is great enough that Sophie tells Nate he’s going to lose them if he doesn’t change his ways. It’s good if your team leader is flawed enough that he’s human, bad if he’s so flawed the team loses faith in him.

COMMUNITY STATUS: Our Problem Is In Our Leadership

5. The Mile-High Job (aired eighth)

The Caper Plot: Get evidence that a conglomerate poisoned a water supply and caused a young girl’s death.

The Community Plot: Sophie distracts the guards, Nate, Eliot, and Parker break in, and . . . Hardison is back at the Leverage office because he overslept after staying up too late playing a video game. The rest of team is working together well until they have to board a plane after which Nate and Sophie argue about when they met until the team has to pull together and finish the job, with Hardison working the ground while they’re in the air. Nate’s still drinking but he’s not drunk so points for that, and once Hardison learns to set his alarm there should be no more trauma in the community. Best in-joke: When Hardison asks Nate what false IDs he and Sophie have on them to travel as a married couple, Nate gives him Tom Baker, Sylvester McCoy, and Peter Davison and Sophie tells him she has a Sarah Jane Baker.

COMMUNITY STATUS: We Have Some Issues, But We’ll Work Them Out

6. The Miracle Job (aired fourth)

The Caper Plot: Save the Nate’s friend’s church from a crooked, violent developer.

The Community Plot: The team comes together on job that’s personal for Nate: saving the church where Nate’s son was baptized, helping a priest who’s been a friend of Nate’s since they were in seminary together (yeah, Nate started out wanting to be a priest, which explains a lot). Hardison objects to faking a miracle but does it anyway, nobody talks about walking away, and Nate doesn’t drink. Progress. (This is also the first of many jobs that will happen because someone from a team member’s past surfaces and needs help, thereby filling in back story for the team member without stopping story. This one’s Nate-centric.)

COMMUNITY STATUS: We’re Getting Better At This

7. The Two-Horse Job (aired third)

The Caper Plot: Take down a Wall Street investor who’s blaming a stable fire on the father of Eliot’s old girlfriend

The Community Plot: The team’s Arch-Nemesis James Sterling makes his debut as the team does a favor for Eliot’s long lost love. As Parker says, Sterling is Evil Nate. Eliot’s the team member on edge this time for personal reasons, and Nate’s on edge, too, because Sterling Never Loses (that was actually a rule in the writers’ room). Things go wrong, Nate tries to pull the plug, Eliot overrules him, but even with all the reversals and glitches (Parker has an unfortunate horse phobia), the team keeps working. At the end, Eliot’s girl tells him she’s glad he’s found a family, something that’s now evident in the way they work together. (A blast-from-the-past Eliot-Centric job, foreshadowed in “The Wedding Job.”)

COMMUNITY STATUS: We’re Beginning To Look A Lot Like Family

8. The Bank Shot Job (aired fifth)

The Caper Plot: The team is finishing up a job when the bank they’re in is robbed by a desperate father and son trying to ransom their mother.

The Community Plot: The team is working like a well-oiled machine when the robbers hit the bank and the job goes to hell. The rest of the episode is the team improvising, with the added pressure of Nate bleeding out from an accidental shooting as the mark takes them hostage and kills the ear comms, which means Hardison, Parker, and Eliot are on their own and do just fine. Parker and Hardison freelance as FBI agents Elmore and Leonard, and Eliot tells the hostage, “Well, ma’am, we be the cavalry.” And when one of the robbers says, “Your people? They’re good?” Nate says, “The best,” and when Hardison says later, “I know, you could have done better,” Nate says, “No, I couldn’t have.” Icing on the cake: Taggert and McSweeten show up to nab the drug dealers. One of my favorite episodes.

COMMUNITY STATUS: We’re Like A Well-Oiled Machine

9. The Stork Job (aired ninth)

The Caper Plot: Take down a Serbian adoption scam.

The Community Plot: This one’s a blast-from-the-past Parker-centric job because she spent her childhood in foster care. Her first time trying to talk to a mark ends badly when she sticks a fork in him after he tells her not every orphan is worth saving, but he really was a creep, so hey, learning experience. That makes her the loose cannon on the team, so she has to learn control. Parker says, “I get it, we’re a team.” Hardison says, “We’re more than a team.” But it gets worse when Parker sees the orphans and decides to save them all right away after the team has agreed to wait until they have a plan. When the other four come get her out of trouble, Hardison tells her she can’t go off on her own: “We’re a team.” Parker says, “We’re more than a team.” The ninth episode of thirteen in the first season, and they’ve moved from team to family.

COMMUNITY STATUS: We’re More Than A Team

Note: This is where I have to express my sympathy to the writers who so carefully arced this community only to have some idiots at the network air the episodes out of order. Because stupidity. ARGH.

Coming up next: “The Juror #6 Job,” with another Parker subplot. Our little girl is growing up. Or at least getting saner, relatively speaking.

Summary of the arc: Hardison and Eliot bicker and they both sometimes give Parker the side-eye, but the three of them have bonded with Nate as Dad and Sophie as Mom. Unfortunately, Dad and Mom still have some issues to work out with the whole team-of-equals thing.

February 23, 2014

Best Movie Poster Ever

I’m definitely losing my grip over this movie:

Although I like writer/director James Gunn’s version better:

It’s that perfectly balanced sense of snark thing.

Also, here’s a place to continue the Antagonist post comments. It got way too close to 300 for comfort.

Leverage Sunday: The Nigerian Job by John Rogers & Chris Downey: Creating a Community

Setting up a community isn’t easy; getting that many people on the page or screen and keeping them all individualized while combining them into a unit normally takes some time, a slow build so that the reader or viewer can get to know each member as the team gradually bonds. Some series–Person of Interest and Arrow, for example–do this over many episodes, adding one member at a time. And then there’s Leverage, a show that dropped five loners into the first episode, fused them into a unit, and never stopped running. The pilot for the series is a great tutorial on how to create a team very quickly while individualizing all its members.

1. Start with the leader.

Even in a team of equals, there has to be somebody in charge, and that leader is crucial because he or she is going to give the group its identity. But because the leader has so much more power than the rest of the group, it’s important to give him or her weak spots so that the group can challenge authority and keep the group identity fluid and the power dynamic equal. In Leverage, the mastermind is Nate Ford, a former insurance investigator, now broken by the death of his son and the collapse of his marriage, drinking himself to death to dull the pain. But Nate isn’t just any insurance investigator; he’s a legend, traveling the globe to track down missing valuables, part of a symbiotic community of detectives and thieves who circle around each other constantly. That means that Nate has intelligence, skills, knowledge, and connections, things that would make him invincible if it weren’t for that drink in his hand.

All of that is set up in the first scene as he’s approached in an airport bar by Victor Dubenich to steal back plans that have been stolen from him, offering Nate both money and revenge on the insurance company that refused to pay for Nate’s son’s treatment, the real chink in his armor of indifference. Nate is the first to be hired, so he’s the only team member in the scene, and the viewer’s full attention is on him. That’s crucial because he’s the one who’s going to define the group, so he has to be established first. The script lampshades Nate’s identity by having Victor tell him that he’s hired three thieves, so now he needs an honest man to lead them.

That “honest man” designation is going to be Nate’s hallmark for the first two seasons, his insistence that he’s not a thief setting him apart from the rest of the cheerfully criminal group until the second season finale when he finally comes to terms with the man he has become, and when asked to identify himself, says, “I’m Nate Ford and I’m a thief.” Possibly a better tag comes from Sophie when she asks him if he doesn’t like being a black king better than a white knight, being the leader of a criminal gang rather than working for somebody else as a good guy, but the truth is he’s both, and that informs the entire crew. Nate now works outside the law to do the good things he did before while his crew now does good things, working outside the law as they’ve always done. They’re all white knights now because they follow Nate’s black king, but because as the series progresses, they all take turns calling the shots, and because Nate becomes part of the team’s community, the black king/white knight designation becomes the team description, too.

2. Add more team members, but make them wildly different from each other, then set them to arguing among themselves to highlight those differences. The next three members of the team arrive all at once and are instantly differentiated in appearance, skill sets, and personality. A black man, a white man,and a woman. A hacker, a hitter, and a thief. An easy-going, good-time guy; a taciturn, brooding guy; a child-like crazy woman. As the series continues, the writers can add layers to these cartoons, making them into complex characters, but in the beginning, the team members need to be as different as possible, no subtlety.

3. Put the team in action right away, before they know each other so they learn each other’s strengths on the job rather than having talking heads explain them to each other. Scenes that have people explain who’s who on the team are useless because nobody remembers words alone, they remember words-and-pictures. Leverage drops three strangers into a computer heist, gives each one a very brief flashback to nail their pasts, and then shows them in action doing what they do very well, imprinting each character distinctly in the viewer’s mind. Then things go wrong and Nate tells them what to do, and together they improvise to finish the job, foreshadowing that they’ll be a team even though each one states clearly that he or she prefers to work alone and the leader prefers not to work with any of them at all.

4. Then put them in a crucible. A team can form slowly over time, learning to trust each other, or they can be melded in a blast furnace of outrage and revenge. An the beginning of the episode, the Leverage team is emotionally distant from each other, brought together for one job only by external forces and the promise of a paycheck, but at the first turning point, they’re put into a crucible–the bad guy cheats them and then tries to blow them up–that gives them a shared emotional goal. By the end of the first episode, they’ve formed a community they’re determined to keep, even if they have to convince their mastermind to keep minding them.

5. Add new members once the basic team is established, but make sure the new member is different from the existing members: different appearance, different skill set, different personality, and must bring something new to the dynamic. In this group, the new kid is Sophie the grifter, an older brunette woman with a seductive personality, the opposite of the other woman in the group, the younger, blonde, socially stunted Parker. Sophie is different in one other respect: she’s the only member of the group chosen by Nate because he’s chased her around the world to recover the things she’s scammed, so he knows how good she is. She’s not only the wild card in this episode’s con, she’s the wild card in Nate’s life.

6. Make sure your stories showcase how the team works together, supporting each other, how, in short, they’re a community, a family. The fun in the Leverage pilot isn’t just in the twisty plot, it’s in watching loners discovering they like working together, a group romance, if you will.

7. Show that the community has a group identity that the individual members value and want to keep. The Leverage pilot did one other thing that was crucial for this team: at the end of the episode it’s revealed that they didn’t just take the bad guy down, they profited from it. Because Hardison is a genius at playing the markets, he can hand every member of the team a huge check, big enough for each of them to retire for life. That means when they follow Nate down the street explaining why they should keep working together, it’s not for the money, it’s because they want to keep the community. The Leverage team pulled their cons for five seasons, but every one rested on the bonding that happened in this first episode.

How They Did It: Plot Analysis:

The community is plot is developed in tandem with the caper plot, each interlocking with and fueling the other.

Act One: I’m Only In This For The Money and I Don’t Like Any of You

The first fifteen minutes is the First Job, Victor hooking Nate, and the team stealing the plans and dropping a virus into the rival’s computers. Hardison, Parker, and Eliot are arguing and resisting Nate’s leadership in the beginning to the point that when things go south, Eliot says “You’re on your own” and prepares to desert them, but by the end when Nate gets them out of trouble, they’re working well together, and it’s all shown in the execution of the theft, the two plots unspooling simultaneously.

The Change of Plans: That Bastard Tried to Kill Us

The first turning point comes when they don’t get paid and Victor tries to blow them up. That swings the caper narrative around from a “Steal back the plans” plot to a “Get even” plot, and the community plot from “this is a one time job” to “let’s work together to get this jerk.” Same characters, new stories.

Act Two: Get Sophie

There’s a nice moment when loner Eliot stops to help a fallen Hardison right before the building blows, especially nice since Hardison had pulled a gun on him only minutes before, but they’re still not a team. That’s demonstrated in the hospital when the three thieves tell each other that they don’t trust any of them. Nate says, “Do you trust me?” and there’s silence until Eliot says, “Of course. You’re an honest man.” Ten minutes later, they’ve escaped and they’re back at Hardison’s place, ready to run, when Nate says, “We can take him,” and after a moment’s thought, all three are back on the team, this time with a common goal to bring down Victor. His team under control once again, Nate makes a final team-building move, getting them a face Victor hasn’t seen: “Let’s go get Sophie.”

The Point of No Return: Let’s Go Break the Law One More Time.”

The mid turning point is when they leave the apartment and put the plan into motion, going into action they can’t retire from. Act Two was the story of four people who’d been attacked and betrayed saving themselves and each other and then agreeing to work together one last time; Act Three will be the team of four plus one in action, changing the plot from “plan” to “execution” and the community from four to five.

Act Three: Get Victor

The Third Act is the Second Job, the team of five eating popcorn and making plans, Sophie and Eliot surprising each other by their common knowledge of a small and evidently hinky town on the Chinese border, Nate surprising everybody with his knowledge of airplanes, all of them beginning to realize the talent they’re surrounded by. The rest of the act is setting up Victor, playing out the scam, problem solving when they hit snags, all of which is new for each one of them and awakens them to the possibilities inherent in teamwork; my favorite example of this is Sophie’s moment of terrified bonding with Parker on the zip line.

The Crisis: Victor Gets Them

The third turning point is when Victor tells his assistant he’s on to them and he’s setting a trap. This is where Leverage cheats in every episode; you watch the team set up the con, but you never have all of the information, which in this case is that Victor’s discovery of their plan is part of their plan. If you know that, all of the tension goes, but if you don’t know that, it’s a cheat since you’ve been part of the team. Normally, I’d be raising hell about this, but I buy it in Leverage: those people lie to everybody, so of course they lie to me. What this TP does for the viewer is change the story from Our Team Is Going To Get Revenge to Our Team Is Going To Get Arrested. The story doesn’t change for the characters, it changes for the viewers.

Act Four: The Biter Bit

Victor springs his trap only to get caught in it by the team’s double con, each part of the plan toppling like dominoes as he tries frantically to stop the fall, while they walk out of the building with files, all dressed alike, a unified team. That is, they come together as Victor falls apart.

The Climax: “I Can Take Your Underpants”

In the caper plot, Victor is utterly and completely defeated and is hauled away by the FBI as Nate returns the stolen plans to his rival along with evidence that Victor was behind the theft.

In the community plot, Hardison passes out checks that give them each enough to retire on, and then the team, in a 180 turn from the first act, tries to convince Nate to stick with them because they want to keep the community and they know it can’t work without him. He tries to walk away, but there’s Sophie, purring “Black king, white knight” at him.

The Denouement/Resolution: We Provide Leverage

The next thing the viewer sees is the new stable world the plot has arced toward, the team talking with a couple in trouble, explaining that they understand that the couple is under a terrible weight, and that what they do is provide leverage to lift that weight. It’s important that its not Nate meeting with this couple alone; Sophie speaks first, then Nate, but all five of them are in the room, clearly a unified community.

Community Status: “This Could Work.”

February 22, 2014

Cherry Saturday: Feb 22, 2014

Today is International World Thinking Day. I think I’ll wait until tomorrow to celebrate; Feb 23 is National Dog Biscuit Appreciation Day, and that always gets a big play here.

February 21, 2014

On August 1 . . .

I never go to the movies anymore. I have a nice large screen TV and my popcorn is better than the theaters. But on August 1, I will kicking small children from my path to get to this . . .

Rocket Raccoon is my spirit animal.

Warning: “Hooked On A Feeling” is going to be in your head for the rest of the day. Sorry about that.

February 20, 2014

Arrow Thursday: Antagonists

If there’s one thing that Arrow does good, it’s Bad. So let’s talk about antagonists.

But first this:

Community Rules: Treat everyone with courtesy and respect. Do not say somebody is wrong, say “I respectfully disagree.” Any comment that refers to anyone in a derogatory way is going to get trashed. Any comment in a sarcastic, snide, or demeaning tone will be trashed even faster. Any comment that refers to John Barrowman as “so far over the top he’s underneath” is okay.

And now, antagonists.

Antagonists are the other half of the engine that drives the story. Protagonists own their stories; their stories happen because they desperately need something (that would be their goals) and they are driven (motivated) to get those somethings. So Indiana Jones must get the Ark of the Covenant to save the world. He goes to Cairo and says, “Where’s the ark?” and somebody says, “Over there,” and he picks it up and takes it home.

There’s something missing in that story: Conflict.

It’s a lousy story because it’s one beat (“Where’s the ark?” “Over there”) that’s not developed (no reason to) and has no impact on the protagonist (“Well, that was easy”). Because it has no impact it doesn’t change the protagonist, and because he doesn’t change, there’s no tension in the story. What do you need to get a story with escalating beats in a tension-filled conflict that has such a tremendous impact on the protagonist that he changes under the pressure? Right, an antagonist.

The antagonist is not necessarily the Bad Guy any more than the protagonist is the Good Guy; he or she is just the character who opposes the protagonist and in fighting back, shapes the plot. You can start with a single premise, and if you swap the protagonist and antagonist, you’ll get a vastly different story because different people are driving and shaping the narrative.

Take the story of a beautiful girl who is abused by her stepmother and fights back to achieve a triumphant wedding with a prince, vanquishing her abusive step-family for all time. Great story. Now take the story of an embattled mother, fighting to protect her daughters against the machinations of her devious stepdaughter. Same plot points but a completely different story. All that changed was who owned the story and who opposed and shaped it.

Now let’s take that mother’s story and change the antagonist to the godmother of the stepdaughter. Now you have an embattled mother in a conflict with another mother figure who has supernatural powers, a mother figure she must defeat if her daughters are to find any kind of happiness, Clash of the Mamas, if you will. Or take that mother and put her in conflict with a rich and powerful prince, a young man who can make or break her daughters’ future. All those stories start with the same premise, involve the same characters, follow the same general plot points, but they’re all different stories because the stories are driven by different protagonists and shaped by different antagonists.

So the story happens because the protagonist needs a goal and sets out to achieve it, but the story gets its shape when the antagonist pushes back; how interesting that shape is depends on how interesting and powerful the antagonist is. The ideal antagonist is stronger, smarter, richer, handsomer, and funnier than the protagonist, which means that the reader/viewer is going to really worry about the protagonist’s chances of success, and the protagonist is going to have to change, learn, and grow to defeat the antagonist. This is why, in many cases, the antagonist is more important to the plot than the protagonist. Not to the story, the story belongs to the protagonist, but to the plot, the events in the story that are shaped by the antagonist’s push-back.

Oh, and one other thing about antagonists: They always think the story belongs to them. That is, they all operate under the mistaken impression that they’re the protagonist. (Actually, all the characters in a story think the story is about them, but we’re talking about antagonists here.) As Arrow producer Marc Guggenheim said in an interview in January:

To the extent that we have a ‘Northern Star’ on the show in terms of bad guys, it’s to always make sure that every villain is the hero of their own story. For us, that principal means that there’s no villain who feels like they’re a villain. They all think that they’re perfectly justified and everything they do is right in its own way.

Okay, enough theory, let’s talk Arrow. As a protagonist, Oliver Queen sets a pretty high bar: he’s strong, smart, rich, charming, and handsome with a dry sense of humor and truly impressive abs. Constructing the perfect antagonist for this guy could mean dreaming up a multi-billionaire of genius level intelligence, hypnotic charm, and more than movie-star good looks who kills at comedy clubs at night and routinely kicks Mr. Universe ass. Or he could be exactly like Oliver, a mirror image that shows Oliver who he’s becoming, a doppelgänger antagonist.

One of the crunchiest things about Oliver as a protagonist is that he’s not that different from his antagonists; that is, he puts on a mask and goes out at night and shoots people. This means that a lot of his antagonists are going to be his double, and that means they’re going to act as foils in the story, characters who are so like him that seeing them side by side points out significant aspects of his character, not only to viewers, but also to Oliver.

Take Malcolm Merlyn, the season one Big Bad.

Malcolm is a billionaire who puts on a hood and goes out at night, plotting to save his city from the cancer that is the Glades (aka, the Bad Part of Town). He thinks he’s a hero, so it’s a good thing we’ve got Oliver, a billionaire who puts on a hood and goes out at night, plotting to save his city from the cancer that is the exploitive one-percenters of the city (aka, the Good Part of Town). Both of them are driven by guilt–Oliver by the death of his father, Merlyn by the death of his wife–both of them were trained on faraway islands during an extended absence from family and friends, both of them favor the arrow as a means of killing, and both of them are wanted by the cops. I could go on, but you get the picture: Oliver and Malcolm are doppelgängers, two halves of the same coin. But, you say, Oliver acts to save the city. So does Malcolm. But Oliver is good, the only one tough enough to go up against the moneyed evil in the city. True, but Malcolm thinks he’s good, better than Oliver, because he’s willing to do the hard thing, the thing Oliver would never do, kill hundreds of low-lifes to clean up the streets. In Malcolm’s mind, he’s better than Oliver. Which is why it’s okay to torture him. Teach the kid a lesson. Also he can catch with one hand the arrows Oliver shoots at him and he’s willing to cross all kinds of boundaries that Oliver won’t. Malcolm may be Oliver’s doppelgänger, but he’s also faster and more ruthless and therefore more powerful, things that make him a great antagonist.

Oliver’s conflict with Malcolm highlights (the foil at work) the flaw in his own plan: he’s killing people. That’s bad. He’s killing them at a slower pace than Malcolm is, but still, he’s set himself up as the same kind of god that Malcolm has, giving himself power over life or death. The last thing Oliver says to Malcolm before he kills him (sort of) is, “Thank you for teaching me what I’m fighting for,” setting up his own turning point, paid off in the first episode of the next season: “The city still needs saving. But not by the Hood. Or some vigilante who’s just crossing names off a list. It needs something more.” Thus Malcolm fulfills the job of every great antagonist: he changes the protagonist through his conflict. (That Malcolm is played by John Barrowman clearly having a fabulous time is just icing on the antagonist cake.)

But not all foils are dopplegangers. That is, a foil is a character who highlights similarities or differences in the character he or she is standing next to, but the foil doesn’t have to be a double, it can be an opposite. Happy, shallow Tommy, for example, was a foil for his best friend, the brooding, damaged Oliver. But antagonists have to be more than happy, shiny people because they have to be stronger than the protagonist. In the case of Count Vertigo, “stronger” means “crazier with no boundaries, a creative bent, and a real head for business.”

I may lose my grip a little here talking about the Count because he’s played by Seth Gabel, who not only owned the role, he franchised it and sold the T-shirt. The Count is as colorful as a big box of Crayolas, if the box was missing a couple of crayons. He’s a successful businessman who’s designed his own popular and dangerous line of drugs, a direct contrast to Oliver Queen who’s refused to become a businessman and take over the family firm. He’s egocentric, colorful and exciting and always moving, characterized by gradiose gestures and wild laughter in contrast to self-sacrificing, mostly silent, mostly still, never smiling Oliver. The impact here is that when Oliver stands beside the Count, he looks grimmer, and when the Count stands beside Oliver, he looks crazier, and their conflict forces them both to the middle: Oliver has to go out of his restrained comfort zone to bring down the Count, and the Count has to take Oliver seriously to escape him. In their final confrontation, the Count does something to shove Oliver not only out of his grim restraint, but also out of his mask: he kidnaps Felicity and forces Oliver to come for her, planning on killing her in front of him, something that’ll put some expression on that blank face at last. And in fact, he really does inspire Oliver to express emotion by killing him three time, putting three arrows into him because he’d taken hostage part of Oliver’s emotional life. Oliver before his conflict with the Count would have finished the job efficiently with one shot. Oliver after the Count needs three arrows because the conflict has pressured him enough that he’s fighting with his heart instead of his brain. And once again a great antagonist does the job he was hired for: he changes the protagonist. (Also, please tell me somebody dragged the Count off to the Lazarus Pit. I don’t care how ridiculous the explanation is, just bring him back.)

Arrow has a wealth of fascinating antagonists to draw from in its source material (who do I have to bribe to get an Auntie Gravity episode?) and the writers have given us great ones, the Huntress, Deadshot, China White, the Dollmaker, and the Bronze Tiger, to name only a few. This season’s Big Bad is Deathstroke, aka Slade, Oliver’s comrade-in-arms from the island, another doppelgänger who thinks he’s the protagonist and who will undoubtedly push Oliver to new realizations about himself in the final episode. As Guggenheim said in the same interview quoted above:

I think heroes are born out of difficult circumstances, and Oliver will learn in the second half of this season that he can say he’s a hero, but the truth of it is that he’s going to have to become a hero through adversity.

The Big Bads shape the A plot, but the antagonists in Arrow’s B plots are just as powerful at shaping Oliver’s personal life. The B-plot antagonist I’m most fond of is Moira Queen, a woman who loves her son to death (she sent him to be tortured and then shot him, but hey, tough love), and who lies and schemes to get what she wants, defending her plots and murders as protecting her children, which they very well may be since Moira, too, sees herself as the protagonist in her admittedly fascinating life story. When last we left Oliver, he had just given his mother the old heave-ho from his life, forgetting that Moira isn’t a helicopter parent, she’s a guided missile. Slade may be Season Two’s Big Bad, but Moira’s going to be shaping Oliver’s life through conflict for a long, long time (I hope). (And a big thank you to Susanna Thompson who took what could have been a cartoon mother and made her into an implacable force of maternal nature.)

And don’t forget the antagonists in Oliver’s romance plots: Shado, Laurel, the Huntress, Felicity, McKenna, Isabel, Sara . . . when does this guy sleep?

The Arrow universe is packed with people shaping Oliver’s life, and that’s a big reason why the stories are so compelling: Arrow is full of fascinating characters struggling in complicated conflicts that fuel wonderful stories. The show may stumble, but Arrow won’t fall as long as its antagonists keep kicking its protagonist up the salmon ladder of self-knowledge and success.

February 19, 2014

Questionable: Beats

Dre Sanders asked:

I would love for you to expound on beats, and how you arrange your scenes with them. Do you track every beat? How do you use them to raise the stakes? What exactly do you consider a beat? I ask this because I’ve read a half dozen different descriptions of beats.

Beats are one of those writing terms that mean pretty much whatever people say they mean. The closest I can come to a universal definition is that they’re a unit of storytelling, but what kind of unit depends on who’s talking. Since I’m the one talking, here’s what I mean by the term:

A beat is unit of conflict. A scene is made up of beats, in the way that a novel is made of scenes. That is, each unit of conflict has a protagonist with a goal and an antagonist who blocks that goal; that dynamic creates conflict and the two characters struggle and at the end of the unit of conflict, one of them wins which either throws the story into the next unit of conflict or ends the narrative. That applies to classic linear novels, acts, scenes, and beats, all units of conflict.

Look at the scene from Moonstruck where Ronnie and Loretta first argue, the first part of which is here:

Protagonist: Loretta

Antagonist: Ronnie

Loretta and Ronnie have come upstairs after his emotional outburst about his brother Johnny causing him to lose his hand many years before. Loretta’s goal is to get Ronnie to agree to come to her wedding to his brother. Ronnie has already refused because he blames Johnny for ruining his life; his goal is to make Loretta go away and tell Johnny that he still hasn’t forgiven him. To get her goal, Loretta has to calm Ronnie down, so she feeds him a steak.

Beat One: Sharp Words

When he’s calm, Ronnie says his girl was right to leave him. This train of thought is not going to get him to the wedding, plus practical Loretta has no time for dramatic self-pity. She tells him he’s stupid. He tells Loretta she doesn’t know anything about him. She tells him he cut off his hand to escape a bad relationship because he’s a wolf who needs to be free, and that the reason he’s alone now is not because of Johnny but because of he’s afraid of what he’ll do to himself if he ends up with the wrong woman again. Ronnie says “What are doing?” Loretta says, “I’m telling you your life!” Ronnie says, “Stop it!” because she’s telling him the truth.

Turning Point: Ronnie changes the subject because he’s just lost that beat conflict, and because he’s really looking at Loretta for the first time: “Why are you marrying Johnny?”

Beat Two: Shouting

Now Loretta’s on the defensive and tells him she’s doing what she has to, and he calls her a fool. They yell at each other about each other’s mistakes, the tension escalates from sharp words to shouting : “A bride without a head!” “A wolf without a foot!” until Johnny knocks the table over.

Turning Point: Set free from his self-pity and misery, Ronnie kisses Loretta.

Beat Three: Physical Passion

Both are overwhelmed by the kiss—Ronnie: “It’s like I’m falling!” Loretta: “I have no luck!”—so Ronnie sweeps her off her feet and tells her he’s taking her to bed.

Turning Point/Climax: Practical Loretta who’s engaged to Ronnie’s brother says, “I don’t care about anything. Take me to the bed.”

Each beat is a unit of conflict, Loretta vs Ronnie, each beat escalates in tension and raises the stakes of the conflict, and the final beat ends the conflict with an act whose consequences will throw the story into the next scene. The scene changes the plot of the story which was about Loretta getting ready to marry Johnny, and it changes the characters in it who are not the same people at the end of the scene that they were at the beginning.

Most of your scenes won’t be this high in emotion, and most of the time, you don’t need to worry about beats; if the scene is working, don’t mess with it, even if it doesn’t have escalating beats. All that matters is that it works on the page, not that it conforms to some abstract set of rules. But when you have a scene that you know is broken, analyzing its beats can be a way to find the broken places.

So how do you use beats to fix a scene?

First of all, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. I know I said that before, but people tend to obsess on this stuff, so if you like the scene, even if you can’t identify any beats, leave it alone.

But you don’t like the scene. Something’s wrong that you can’t put your finger on, but it is definitely not working. Look, not all scenes are worth saving; some are so bad that trying to fix them is just washing garbage. So the first thing you ask yourself is, “Do I need this scene?” If the answer is, “No,” cut it and move on. The second thing you ask yourself is, “Since I need this scene because of X (fill in your own reason), is there another way I can accomplish X by folding it into a scene that is working or writing a brand new scene?” If the answer is “Yes,” do that. If the answer is “No,” you’re stuck and you’re going to have to fix that scene. That’s when beats come into play.

So you go back to the classic, basic conflict questions:

Who is my protagonist? What does she want?

The protagonist is the person who owns the scene and what she wants is her goal. If you’re not sure who the protagonist is, pick one of the characters and give her the scene. If you’re not sure what her goal is in the scene, give her one based on your best guess from what’s there.

Then you go back to the second basic question:

Who is my antagonist? What does he want?

Ninety percent of the time, this is where your scene went south: No antagonist. You have people in the scene with your protagonist, but there’s no conflict. Scenes with no conflict are pretty much just Chat, that murderer of Story. So look at the scene and find somebody with motivation to block your protagonist in pursuit of her goal. If there isn’t one in there, seriously consider cutting the whole thing. No? Okay, put in an antagonist with a clear goal that blocks your protagonist.

NOW you’re ready to look at beats. Figure out the steps of your conflict (Arguing, Shouting, Kissing) and divide the scene into those parts. Then treat each part as its own unit of conflict. The protagonist wants this and does this, the antagonist responds by doing this, the interaction grows more heated until one or the other is pushed into doing something he or she wouldn’t normally do, like Johnny questioning Loretta about her life instead of moaning about his own: “Why are you marrying my brother?”

That broken barrier turns the story/scene in a new direction, leading to the next beat, which continues to build the escalating exchange, just at a higher level: arguing escalates to shouting.

Lather, rinse, repeat for each piece of the scene. Each beat should have greater tension and higher stakes, pushing the protagonist and antagonist toward the final moment, the climax, when one wins and one loses and the story changes (because every scene in your story should move the plot and impact character).

Obviously if you do a beat analysis for every scene in your story, you’re going to lose your freaking mind, so again, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

So how do I do it? The opening scene to a story I’m writing is not working. That’s okay, it’s a first draft, it’s not supposed to be great, but I’m not sure I should even keep it because it mainly serves to move the main character across a street and into a house where she sees the antagonist. Please note, she’s not in conflict with him, she just sees him. Intellectually, I know I should just cut this scene. Emotionally, I want to keep it, I just don’t know why. So first, I break it into beats:

1. Zo and Gleep are across the street from Dark House, Gleep explaining the situation. No conflict, just exchange of information.

2. Zo follows Gleep into the house and notices significant details. No conflict.

3. Zo looks through a doorway, sees the story antagonist, and evaluates the situation and telling Gleep what to do. No conflict.

Usually when I break a scene down by beats, I find out that one beat has no conflict or that the conflict circles the drain instead of escalating in each beat, but this sucker has NO conflict. It should be cut.

I want to keep it.

So back to beats and conflict. This is Zo vs. Gleep. Zo is Gleep’s foster mother. Gleep is ten. Zo’s goal is to get the rest of her foster kids out of the house without drawing any attention from the police. Gleep’s goal is to get Zo into the house to solve a problem there. So Zo’s goal to get the kids out and Gleep’s goal to get Zo in aren’t in direct conflict. Crap.

First beat is Gleep getting Zo to go into the house. Zo says no, she’s not going to break and enter; Gleep refuses to explain what happened, just that the kids are inside and the cops have them. Zo has to go in to get her kids; she’s exasperated, but not afraid. Gleep wins this beat.

Turning Point: Gleep pulls Zo into the street and she follows. The scene/story turns from Zo insisting the kids come out of the house because she’s not going to break in to Zo crossing that boundary and agreeing to go in to get them.

Second beat is Zo at the door of the house which has a security spell on it, which shows her that there’s more going on than just kids breaking into a house. Gleep goes in before she can stop her and after an argument, soshe tells Gleep to invite her in.

Turning Point: Zo goes in and feels the evil that permeates the house and knows that this isn’t about saving her kids from the cops, it’s about saving her kids from the house.

Third beat: Zo looks through a doorway and sees that the cops that have the kids are high level and smart. Caught between the dangers of the house and the cops, she makes and implements a plan to get the kids out, overruling Gleep’s insistence that she has to go into the room.

Turning Point/Climax: Gleep shoves open the door and walks in, blowing their cover, and Zo is discovered, too. The story has changed from Zo trying to get her kids out of the house and away from the cops to Zo talking the cops out of arresting her kids as fast as possible to get them all out of the house.

That’s still not good, I still don’t know why that scene can’t be cut, and it’s still too much description, most of it lousy, but now I have a plan that at least has escalating action and emotion, which means I can do the rewrite and then leave the first scene there until I have the entire story finished, then go back and sharpen it to foreshadow the ending. Or cut it which is probably what I should have done a long time ago.

That’s how I use beats.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

February 17, 2014

The Romance Contract

I’ve been e-mailing with Pam Regis, Argh’s Academic in Residence, about the romance contract, the agreement that romance writers make with their readers. From Pam’s first e-mail:

The unspoken contract in romance fiction is that the parties to the courtship will end up together. They’ll overcome whatever barriers there are to that ending-up-together and commit to each other. For most of the genre’s history, the outward sign of that commitment was marriage–no longer a requirement, although still quite common.

This is pretty basic; it’s the same as the contract that mystery writers make with their readers: The ending will see this mystery solved. That sense of justice restored and narrative completed pervades much of storytelling; at the beginning, the stable world of the story is plunged into chaos and at the end, justice and stability are achieved again, albeit not necessarily the same stability. In the romance, that justice is emotional: good, flawed people find each other, make mistakes, grow, and in the end commit to each other and form a stable relationship, a bond made possible because they’ve fought the good fight.

But the reader can’t follow the good fight unless that contract is in place. That is, just as a mystery reader has to know who the detective is and what the crime is, so a romance reader needs to know who her lovers are. Even if the romance in the story is relegated to the subplot/B plot, that contract has to be in place. Romance readers don’t need the romance resolved right away, and in fact the harder the romance is to navigate, the better the romance plot because stress causes adrenalin which makes people vulnerable and impulsive which leads to more emotional upheaval; a romance under stress is a perfect example of emotional escalation. But readers do need to know who the parties to the romance contract are. Before the contract, the story is just a lot of people running around screwing up personal interactions. After the contract, those same screw-ups become barriers to and escalations of a clear plot. If you’re going to write romance, even as a subplot, you need that contract.

I’d asked Pam about Arrow because it’s currently hurtling toward one of the biggest train wrecks of romance writing I’ve ever seen. Here’s what she said about the Arrow romance contract:

Fulfilling this contract presupposes that the reader/viewer can tell who the parties to the courtship ARE. So, in Arrow, the audience easily identifies Oliver as one of the parties to the courtship–he’s the protagonist whose life changed while he was cheating on his girlfriend with his girlfriend’s sister: cue shipwreck, island, superpowers. Not to mention abs.

But who is the other party to the courtship? In romance (hetero and lesbian), readers/viewers focus on the female, for all that male romance characters now share point of view and have detailed character arcs. So, who is she? (Oliver seems to be hetero, so I’m not asking who he is, although the homosocial aspects of superhero fiction are pretty interesting. I’m also not asking who they are, because the assumption seems to be that this will not be a menage, although with these writers, who knows?)

So, who is she?

Of course, Arrow isn’t a romance, it just has romantic subplots, but even those need a romance contract. Take the Oliver/Helena romance. The contract was established early, supported by the connection they made due to their matching pathologies and then broken by the fact that Helena was a lot crazier than Oliver. It wasn’t a long romance, but it had a clear contract, a clear arc, and an understandable ending. Nobody ever asked during that subplot, “Who is she?” “She” was Helena.

Here’s Pam’s analysis of the Arrow romances:

We have Laurel: the barrier here is that Oliver slept with her sister. Your term, “bleah,” seems a bit mild here. Nothing like destroying a romantic relationship and a family in one go.

We have Felicity: the IT girl who, when she showed up, the viewers said: “That one.” I recall that one of the commenters on Argh reports thinking, “There she is” when Felicity arrived. So the part of the romance contract that requires a viewer to be able to identify the parties to the courtship seemed to be fulfilled for many viewers: Felicity from IT was it. Writers of fan fiction proceeded to write Oliver/Felicity scenes.

Ending the introduction of potential female parties to the courtship here would have left the I-know-who-is-in-the-courtship requirement of the romance contract fulfilled. The writers of Arrow, following the romance contract, would pursue the Felicity relationship, presumably inventing many barriers to its ultimate fulfillment.

But then Oliver kisses Sara. Now who is Oliver courting? Viewers don’t know anymore. They thought they did, but now they don’t.

This for me is the real problem with the Sara kiss: it breaks a contract that many viewers made with the writers and that the writers seemed to acknowledge in later Oliver/Felicity scenes. When you add to that the original contract the writers did make with the viewers, the Oliver/Laurel contract, it puts the writers in the shoes of that guy or girl who flirts with you, tell you that you have nice eyes, promises to call, and then makes out with somebody else at the end of the bar. It’s not that anybody is expecting Oliver to show up with a ring and propose to Felicity or Laurel, it’s that the writers are flirting with too many love interests simultaneously. If they pick a lane, if for example, they make an Oliver/Laurel contract and fulfill it, finishing that romance plot,and then make a new contract with the viewer for an Oliver/Felicity or an Oliver/Sara romance, the viewer can still keep a grip on the story. The length of the contract isn’t particularly important, either; there just has to be a contract.

A romance plot that refuses to identify the parties to the contract becomes a story with blank spaces that the reader has to fill in. This is why writing romances with more than one possible love interest can be such a dicey proposition: if a writer asks the question “Which one?” readers will answer, and if they pick a different love interest from the one the writer chose, the ending of the romance will be a failed catharsis of Biblical proportions. It may seem reductive that the reader has to know the players in a romance up front, but it’s as absurd to have a romance that leaves the identities of the lovers uncertain as it is to have a mystery that’s not sure if there’s been a crime or who the detective is. So if you leave those blank spaces in the text, the reader fills them in. Again, Pam’s take on this:

So the viewers who also write fan fiction, who have identified Felicity as Oliver’s intended, rescue her from her cheating suitor. They pair her with “anyone but Oliver,” including, for a perfect pay-back, Sara. Felicity and Sara both cheat on Oliver–with each other. These fan fiction writers react to the violation of the romance contract by writing scenes that restore romantic justice to the built world of Arrow. But Arrow is primarily about justice of another sort–saving innocent lives, saving the city–warrior justice.

Arrow’s writers have got a lot of courtship possibilities in play for Oliver. And it seems they are perfectly willing to introduce a new romantic element without much set-up: Oliver kissing Sara.

Are they adding characters to the mix, then waiting–not very long in the internet age–to see what the fan base thinks of the reconfigured relationships? To what extent can they violate the romance contract and still keep viewers?

At what point does viewer input make the viewers co-writers of the narrative? That’s the ultimate question.

For me, the writer not the academic, the ultimate question is more practical: at what point does the lack of contract mean that I lose control of the story because the reader rips it out of my hands to make it go in the direction she wants, abandoning my book to dream/write her own fantasies? At what point do I destroy my own narrative by making the teasing of expectation more important than actually telling the story? If I’m going to switch love interests, how much rage can I overcome in my reader to make her invest in the second love interest?

If requiring a contract seems to limit a plot too much, remember that a romance contract is between the writer and the reader, it’s not between the characters; they may not even be aware there’s a romance in their future. That means that both characters in the romance plot can see other people, have other romances (which complicate the arc of the contracted romance), delay acknowledgment of the seriousness of the relationship, pretty much do what they want, as long as what they’re doing doesn’t destroy the future of the relationship that the writer contracted with the reader. Their experiences are part of the romance arc, so the writer has to make sure that those experiences with others move that contracted romance plot, that the things the lovers learn from the other relationships inform the true love story. That means a writer has a lot of leeway even with a contract in place.

Therefore, knowing the contracted love interest on Arrow would clarify the Oliver/Sara kiss because viewers could tie it to the contracted plot; how they’d tie it would depend on who the love interest is. If the writers are abiding by the original Oliver/Laurel contract, they just ended that romance arc; “You slept with my sister twice” is not a segue to a happy ending. If they’re planning long term for Oliver/Felicity, viewers can adapt what’s happening to that romance: Oliver is denying his feelings for Felicity, Oliver is keeping the Arrow team on a professional basis, Oliver hasn’t caught on that he’s in love with Felicity, there are any number of explanations a Felicity ‘shipper can come up with to resolve that action as long as she knows Felicity is the other half of the romance contract. But if they’re planning an Oliver/Sara relationship, they have a problem because there’s no contract; that is, the romance wasn’t foreshadowed in any way that the viewer could say, “Oh, there she is, the other half of Oliver’s romance plot,” so an out-of-the-blue kiss just leads to a general “WTF?” The idea of teasing the reader/viewer with a knowing “wait and see, we have a plan” just doesn’t work in a romance plot. The romance reader is good with insurmountable odds and will wait a fairly long time to find out how the lovers will resolve everything, but she is not good with not knowing what the hell is going on.

Bottom line: To tell an effective romance narrative, you need to establish that romance contract.

Where Everybody Knows Your Name: Community in Storytelling

Lately, I am fascinated by community in stories. I’ve always known it was important, but a couple of weeks ago I realized that one of the novels I’m working on has a community as its protagonist; that is, it’s a group of stories that taken together, show how this community was formed. The individual stories have individual protagonists, but the book is about this group of people who through the struggles in their various plots are thrown together and bond. And that means I need to know a lot more about how to build and use communities (teams, families, whatever) in fiction. So fair warning: I’m going to be doing a lot of posts about community. I can do that, it’s my blog. (Hey, it’s a step up from dog pictures which I have moved to Refab, so count your blessings.)

Community is one of the most powerful storytelling hooks. The more we trade the sense of real, physical attachment to a group for the virtual community of the internet (Hi, Argh People), the more we need to experience connection vicariously in our stories. The pleasure of reading about a lone protagonist finding a community that supports her and loves her, and the fun of seeing interesting characters come together to become a team are both a kind of love story: people who were strangers commit to each other in a unit that makes them stronger and safer and happier. The successful community story is like the successful love story: the people in it are better together.

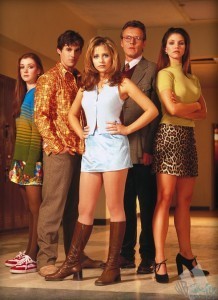

Think of classic TV shows like Friends (“I’ll be there for you”) and Cheers (“You need to go where everybody knows your name”). Buffy was nothing without the Scoobies, Finch in Person of Interest is helpless without the Machine Gang, Oliver on Arrow wasn’t all that interesting until first Diggle and then Felicity made Team Arrow (“Stop”). Frank and Sarah were fun in Red, but the story really took off when they picked up Marvin and the Pig, and then Joe, and then Victoria, and then Ivan, each addition making the team stronger and smarter. Half the fun of community in fiction is seeing how that community assembles, working out their differences and growing stronger with each addition. The reader’s pay-off in those stories is the vicarious sense of belonging, that secret knowledge that if we walked into the bar in Cheers, everybody would know our names; that if we went to Central Perk, they’d make room for us on the couch, that if we stopped by The Pie Hole, Olive would remember our favorite slice. Because we take the journey with the characters, we’re part of their team.

The big problem with writing community is that Community = A Lot of People. If you’re writing a romance, you need to put two love interests vividly on the page and then show them interacting, struggling with each other, negotiating the terms of the partnership, while avoiding long scenes where the two talk about the relationship in favor of short scenes where the two do things that change, grow, and intensify the relationship. Think that’s difficult? Now change “two” to “five.”

So here’s what I think I know about writing community so far:

1. Start with the central figure of the group, the leader/mastermind/source of power.

If you look at the pictures in this post, most have a first-among-equals, a leader who anchors the team (Friends is the exception). That character is important because the personality of the character who leads the group is going to characterize the group, which means you get him or her on the page first. She or he is, as a writing prof of mine once said, the stout stake that everyone and everything in the story is tied to. Without Buffy, the Scoobie Gang would be aimless. Without Finch, the Machine Gang would have no focused moral purpose. Without Frank, the Red Gang would just shoot everybody. When you introduce your protagonist/leader first, you introduce the community that’s to come. That means that not only must your protagonist be all the things a regular protagonist is–fascinating, driven by a goal, pro-active–he or she must have a purpose that is difficult enough to require a focused team to achieve. Any protagonist can get a little help from friends; the team leader protagonist has a goal that’s so difficult and complex that he or she needs people who will form one unit to achieve a single goal, his goal.

That means the character of the leader is uber-powerful in shaping the text. For some stories, his character is uber-powerful in the story, too–the fact that Frank has no flaws doesn’t hurt Red although his weakness (Sarah) complicates things nicely and puts a jet pack on his motivations–but if you’re interested in the dynamics of the group, giving the leader a weakness that the rest of the group acknowledges and adapts to can balance the power structure in the group. Sam, the leader of the Cheers barflies, is handsome, famous, and successful. He’s also dumb as a rock, which means that Carla, Diane, and Norm have a level playing field in their negotiations with him (and everybody takes care of Cliff and Coach). A flawed leader means that the group dynamics are less predictable, more dynamic, and a lot more fun.

2. Once you have your leader, build your team around him or her by first putting the group on the page as individuals. That is, you need your group members to be distinctly different from each other so that it’s easy to tell who’s who. If they all look, sound, and work alike, your reader is going to be pulled out of the story trying to identify who’s doing what.

The group above is three dark-haired guys in suits and three-dark haired women in dark jackets and pants. I watched four episodes and still couldn’t remember people’s names.

Now look at this:

Which group do you want to know more about?

3. Once you have your group members, you have to introduce them to the reader. Carefully. The easiest and clearest way to do this is to introduce the characters one at a time, establishing each of their personalities and their relationship with the leader before moving on to the next. Red builds its team that way, the Scooby Gang was introduced to Buffy one at a time, the Machine Gang began with only Finch and Reese. Or you can bring several of them together in conflict and under pressure, and watch them demonstrate who they are and what they bring to the table as the team hits the ground running, as in Leverage where the different characters are hired for one job and become a team under the leadership of Nate Ford, motivated by a joint desire for payback.

However you introduce the members, it’s important to establish their differences up front, especially their skill sets, their personalities, and their flaws and weaknesses. The “You complete me” trope that’s so awful in romances is actually good in building communities; each member is a part of the whole and without each member the whole is incomplete. That means you don’t want any duplicate skill sets. I’m a huge Person of Interest fan, and I love the characters of Reese and Shaw, but they’re duplicates; if the team loses one, the other can do exactly the same things so the whole is not diminished. But if that team loses Finch or Fusco, there’s a hole there that’s not easy to fix. It’s one reason the team is still reeling from the loss of Carter: she was essential.

The same goes for personalities: Friends‘ control freak Monica, material girl Rachel, free spirit dimwit Phoebe are impossible to confuse, as are smart but doofus Ross, tricky Chandler, and sweet dimwit Joey. (Yes, that’s two sweet dimwits, but one’s male and one’s female, so that helps a lot.) The point isn’t just to make sure they’re all different, the point is to make sure they interlock to make the community/team stronger than the sum of its parts. Monica without Rachel and Phoebe would be an uptight mess living a tidy but dreary life; Rachel without Monica and Phoebe would be broke and immature and living with her mother; Phoebe without Monica and Rachel would be wandering the streets singing “Smelly Cat.” They really are better together.

4. Once you have that community established, the fun begins. In the same way that conflict shapes and arcs a protagonist, so conflict shapes and arcs a community, but in infinitely more complex ways because within the community, that conflict is also sparking individual character change. That means a dynamic community is constantly reinventing itself, moving like a series of gears as each character changes and in turn changes the others; everybody has to accommodate everybody else or the community breaks apart. You may have to establish those community members as cartoon-simple in the beginning, but the moment the community begins to act, the characters of its members become more layered, their complexities made evident because of their interactions on the page.

But that’s just the surface stuff. There’s a lot more that I want to know about how community works in storytelling, so for the next fourteen weeks our give-me-something-to-watch-until-this-nightmare-winter-is-over TV Sundays series is going to be Leverage, a show about a group of criminals led by a former insurance investigator who band to together in a kind of Equalizer Club to help the helpless and kneecap the predatory.

If you want to play along, all five seasons are streaming on Hulu, Amazon, and Netflix. My tentative plan (everything is subject to change) is:

Feb 23 “The Nigerian Job,” by John Rogers & Chris Downey (1-1) Introducing a Community

Mar 2 “The Juror # 6 Job” by Rebecca Kirsch (1-11) Integrating a Single-Character Subplot

Mar 9 “The First and Second David Jobs” by John Rogers & Chris Downey (1-12/13) The Recurring Nemesis

Mar 16 “The Beantown Bailout Job” by John Rogers (2-1) Community Dynamics

Mar 23 “The Two Live Crew Job” by Amy Berg & John Rogers (2-7) Foils and

Doppelgängers

Mar 30 “The Jailhouse Job” by John Rogers (3-1)

Apr 6 “The Inside Job” by Geoffrey Thorne (3-3) Integrating Single Character Back Story

Apr 13 “The Rashomen Job” by John Rogers (3-11) POV

Apr 20 “The San Lorenzo Job” by John Rogers & M. Scott Veach

Apr 27 “The Lonely Hearts Job” Kerry Glover (4-15) Integrating Romance

May 4 “The Radio Job/The Last Dam Job” Chris Downey & Paul Guyot; John Rogers (4-17/18) Beginnings, Endings, and Call Backs

May 11 “The Broken Wing Job” by M. Scott Veach & Rebecca Kirsch (5-8) Character Arc

May 18 “The Frame Up Job” by Geoffrey Thorne & Jeremy Bernstein (5-10) The Homage

May 25 “The Long Good-bye Job” Chris Downey & John Rogers (5-15) Endings

Leverage is a lot of fun: it’s light, it moves fast, it’s not depressing, I never feel the urge to slap the protagonist, and it’s a great vivid, dynamic community. It’s the closest thing I could think of to sunshine and tulips until the real things arrive. (Okay, that would actually have been Pushing Daisies, but a good vengeance plot always makes me feel warm and sunny, so we’re going with Leverage.) If you’re not familiar with the show, this YouTube video gives you all five seasons in three minutes.

Questions? Suggestions? Complaints? Put ‘em below.

Note: The first season episodes were aired out of order (why do networks DO that?) so if you’re catching up on the entire first season, here’s the intended order of the episodes with the ones we’re watching in bold:

Nigerian (1), Homecoming (2), Wedding (7), Snow (9), Mile-High (8), Miracle (4), Two-Horse (3), Bank Shot (5), Stork (6), Juror #6 (11), 12-Step (10), First David (12), Second David (13).

February 16, 2014

Sherlock Sunday: His Last Vow by Stephen Moffat

Talk about a Hail Mary pass . . .

And Sherlock returns to the business of telling stories with a protagonist you don’t want to slap (mostly) and an antagonist you want to stomp. Lots of twists and turns, surprises and reversals, huge suspensions of disbelief, but then that’s Sherlock for you. The story hold together, the conclusion is satisfying, and they’ve got me back for another season.