Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 278

February 5, 2014

“Screenwriters: Don’t Do This” Infographic

An anonymous script reader created this info graphic that includes a list of thirty-seven things he found were the common mistakes in scripts after reading 300 of them:

Not surprisingly, most of these are the things that go wrong in novels, too. Starting too late, not enough conflict, weak endings, all the classics are there. Click the link for an expandable image plus close ups.

February 4, 2014

Questionable: Evaluating the First Draft

Jilly asked:

I’d love to know how you evaluate your story once you reach the end of your first draft – how do you decide what to keep and what to change?

Short answer: Keep whatever’s working and tells your story, cut or revise whatever’s not working, cut anything that gets in the way of your story even if it’s working.

Long answer: The great thing about finishing a first draft (besides just finishing the damn thing) is that I now have my entire story before me. So after struggling with separate narrative units, looking at beats and scenes alone, I can sit down, read the entire thing at once, and see what the story really is about. At that point it’s a lot easier to find the parts that slow down or repeat, the parts that feel like they’re missing something important, the parts that don’t belong in the book at all. (In every book, I have a stretch that I read and think, “WTF?” and have no idea what I was going for when I wrote it.) Because I write books in small parts over a long period of time, I really can’t know what the story I’m writing is about until it’s finished and I read it as a whole, so the finished first draft is really the first time I meet the story I’ve written.

In that first read-through, I find the scenes that were fine when I wrote them but now are scenes that I skim as I read the whole thing, trying to get to a good part, and I figure out why I’m skimming them, and then I either rewrite them to make them unskimmable good parts or I cut them. I look at my character arcs and find the places where my people suddenly lurch from one kind of character to another, and I either rewrite the lurch so the evolution is smooth or I add in the missing scene to change the lurch to an arc. I find the plot holes and plug them up; I trim the chat so it becomes conflict, and I cut like crazy for clarity, especially adverbs and adjectives which almost always make the narrative sluggish (strong nouns and verbs, people). I do one run through where I just search for “ly” words. Amazing how much you can cut doing that.

Then I get into serious rewriting. The key is understanding the difference between the first draft and the next drafts. The first draft is the place where I swing wide. It’s the place where I go over the top, write all the stuff I want to write, explore any byway that seems attractive. I do not censor or edit myself in the first draft because that shuts down the Girls. So writing a first draft is Anything Goes, but rewriting the first draft is A Lot of This Is Going To Go. That’s because the rewrite of the first draft changes the writer-based, don’t-look-down draft to a reader-based, communication draft. The first draft is an exploration of creativity, the second draft is making that creativity organized and understandable, streamlining it so that my reader can find and follow my story easily. The first draft is for me; everything after that is for her. So my goal for the second draft is clarity: cut or rewrite anything that doesn’t make sense or that obscures the through line for my story.

After that, once I have the big kinks worked out, I break it into acts and see where the turning points/big character shifts happen and how they’re spaced, rejiggering things so that they come closer and closer together, fixing the pacing so the reader gets the sense that book speeds up as she gets closer to the end.

Then I print it all out and do a paper edit. It’s amazing what I find when I shift from the screen to paper.

Then I key in those changes, print it out again, and read it out loud, doing a second paper edit. It’s amazing what I find when I hear the story instead of reading it in my head. And I key in those changes.

And then I turn it over to the betas because I’ve been working on it for so long I can’t see it anymore. And they tell me things and I think, “Oh, hell, why didn’t I see that?” but I couldn’t because I’ve been looking at it for so long I can’t see anything.

Lather, rinse, repeat. Eventually, it’s still not done, but I am, I just can’t work on it anymore and I send it wherever it’s going to go, agent or editor or whatever, and then I take their feedback and do another edit.

Then it goes to copy edit and I get my pages back. My editor is great about telling copy editors not to change anything and to put notes in the margin instead, so that makes things faster because I can just cross out the notes that are insane and fix the rest. I’m allowed to rewrite on the copy edit and I always do, but if I change more than 10%, I have to pay to get the thing re-keyed or whatever they do; by that time, though, I’ve got it close enough that I never get near 10%. Usually it’s just one or two scenes that need significant work.

And then I send it back and that’s it, the next I see it, it’ll be published and unchangeable.

And then I start the next one.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

February 3, 2014

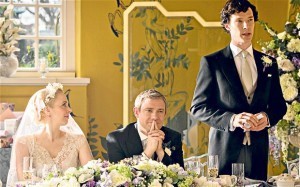

Next Sherlock Sunday: The Sign of the Three by Gatiss, Thompson, and Moffat

I’m fairly bitter about this episode, so you may want to skip my post next week. I took notes as I watched this the second time and then talked about the problems, but there’s no focus on a craft topic because there was just too much wrong with it. I’d say if “His Last Vow” is this bad, I won’t watch the show again, but I’d be lying. I’ll come back just to watch Cumberbatch and Freeman and Stubbs and Graves and Brealey and Gatiss, not to mention Abbington and Pulver. They’re all so damn good, even in a cold mess like this. But I’m gonna bitch about it . . .

February 2, 2014

Sherlock Sunday: The Empty Hearse by Mark Gatiss

The topic for today is The Dickhead Protagonist.

The Dickhead Protagonist is without charm or wit, so there’s nothing to alleviate the cruelty and selfishness of what he does. The Dickhead is so convinced of his own worth and so consumed by his own amusement that he fails to see the emotional damage he inflicts on those around him; his lack of empathy only handicaps him further. The Dickhead is usually committed by writers who have fallen in love with their protagonists and can’t see his flaws, just as a fawning mother will excuse any atrocity her little snowflake commits. Nothing can destroy a story faster than a Dickhead Protagonist (applies to both genders) although a fragmented, unfocused plot that exists merely to showcase how clever the Dickhead is runs a close second.

And now, let us examine “The Empty Hearse.”

In this episode, the writer has taken one of the most appealing protagonists of all time and emphasized his weaknesses while eliminating his strengths to create A Fathead of Epic Proportions, a man we cheer to see hit repeatedly by his best friend. But the worst of the failings here is the abysmal story structure. Of approximately eight-five minutes of story, about twenty are given to the underground bomber plot, the only mystery in the episode. Okay, fine, so maybe the bomb plot is a subplot. Then what’s the main plot? It’s evidently got to do something with Sherlock’s sadistic sense of humor because that’s what keeps cropping up. This is one of the most mean-spirited stories I’ve ever watched.

The first three minutes is a Gotcha, fooling the reader into thinking that it’s the real explanation only to reveal at the end that it’s Anderson’s latest theory and not what really happened. I’m assuming this is supposed to be funny, the writer putting one over on us, but really? Just annoying.

The next four minute are the capture and torture of Sherlock by the last of Moriarty’s people, at the end of which an equally sadistic Mycroft tells Sherlock he’s needed back home because an underground terrorist group is going to blow up London. Why we had to watch Sherlock be tortured is unclear; the information needed about the plot is elaborated on later in Mycroft’s office, so this is a complete waste of story real estate.

Then eight minutes of back story info dump of Sherlock and Mycroft telling each things and John and Mrs. Hudson catching up, followed by eleven minutes of John hitting Sherlock, followed by thirty seconds of Sherlock telling Molly and Lestrade he’s back, followed by another Gotcha, this time a fan explanation that ends with the news that Sherlock is back made public. Then a bunch of vignettes of Sherlock muttering at maps and John and Mary working at his office, followed by Sherlock and Mycroft CHATTING while they play Operation. At this point, I was so confused and so bitter about being yanked around, that if this had been the pilot for the series, I’d have left. Thirty-seven minutes in, there’s a plot to blow up London, and Mycroft is saying, “I’m not lonely.” WTF? That’s followed by nine minutes of Sherlock and Molly doing miscellaneous detection, finishing up with the videos of the trains which is FINALLY the bomb plot, the ONLY plot in this episode so far.

So forty-six minutes in, half way through the story, and we know there’s a terrorist group planning to bomb London, something we knew at the four-minute mark. Look, I know they had a lot to set up here, all of Sherlock’s homecoming stuff, but they could have cut about thirty-five minutes of the sadistic jokes, info dump, and miscellany and made his homecoming part of his attempts to solve the bomb plot. As it is, this was forty minute wasted on the writer being clever and Sherlock being a dick. This isn’t Sherlock reverting to who he was in the pilot episode, that Sherlock was detached, but he had dignity. He didn’t play sadistic jokes and he wasn’t this overtly arrogant. He was QUIETLY arrogant. This Sherlock is blowhard, a clown, unpleasant to watch, all of which is clearly demonstrated in the forty minutes of unnecessary garbage they front loaded this episode with.

Then forty-six minutes in, John gets kidnapped. Why? Damned if I know. I can’t see any way that it interacted with the bomb plot. Was it supposed to distract Sherlock from defusing the bomb? Then why plan it early enough that he can do both? But Sherlock and Mary rush to the scene on a motorcycle and save John the Victim, who deserves better.

Nine minutes later we meet Sherlock’s parents, who are very normal boring people, and I don’t believe it. Nice chatty people like that would not have raised two emotionally damaged sociopaths like Mycroft and Sherlock. It makes no sense. But, hey, it’s a JOKE!. Then John asks Sherlock why he was kidnapped, and Sherlock says, “I don’t know,” but then BAZINGA he suddenly understands that “underground terrorist attack” means that terrorists are going to attack the underground! And it’s only taken our genius detective ONE HOUR to figure that out. Two-thirds of the show.

During the next sixteen minutes, they spring into action, running through a lot of subway tunnels (you can tell Gatiss wrote this), finding the bomb which Sherlock cannot defuse, so John, at the point of death, tells Sherlock that he was the best and finest man John’s ever known and then shuts his eyes waiting for death.

At which point we switch to Sherlock explaining to Anderson how he faked his death. Because we’re really going to worry that the two leads in this show might possibly be blown up. Sherlock explains for two minutes and then spends another minute breaking Anderson down before he tells him that’s not how he did it and leaves.

Back in the subway, Sherlock switches the bomb to “off” and laughs at John’s pain. Because he’s a dickhead. Also, now I hate him. Moran gets arrested. Back at the flat, everybody’s celebrating when Molly brings in her new man who looks a lot like Sherlock; significant looks are exchanged, snickers are smothered, general asshattery reigns as Molly says, “I’ve moved on,” clearly not having moved on. Because that’s a JOKE. Then we get thirty seconds of the Big Bad watching multiple screens which tells us nothing. The End.

I outlined this whole episode and I still don’t know what the hell they were going after. It’s a complete mess, an indulgent morass of sadistic jokes, gotchas, scenes of people running, chat, and torture, glued to about twenty minutes of actual plot. This is why I don’t deliberately choose bad writing for us to watch. Everything you could learn from this you already know: establish your main plot clearly, anchor it with a strong antagonist, and don’t make your protagonist a dick.

I think much of my outrage at what has been done to this character stems from the deep love I had for him after the second season. Irene had made him vulnerable, Moriarty had shown him capable of sacrifice for the people he loved, and now this episode shows that none of that stuck and that he has, in fact, become worse than he was in the first episode of season one, where he was at least not intentionally cruel to people. They murdered my Sherlock and brought back an imposter from the grave.

Next week: The Dickhead Goes to a Wedding

February 1, 2014

Cherry Saturday: Feb. 1, 2014

February is Creative Romance Month. Try to control yourselves.

January 31, 2014

Questionable: Conflict in Romance

Carol wrote:

It’s the conflict in every scene that throws me for a loop. What about romance? Yes, there needs to be conflict or it’s boring, but if it’s all conflict, I can’t buy them having a HEA. Doesn’t there need to be some parts where they are in accord? What about after the Big Bad Thing has happened? I would think the character needs to react, to process the loss, before he/she can think what to do next, especially if it is a major loss. And if the scene begins when the conflict starts and ends when the conflict stops, when does the reader get a breather?

I understand the definition of conflict, but … Man, I can’t even come up with a coherent question. How about – How do you use conflict? Especially the more subtle ways.

Conflict in general is pretty simple. Conflict in romance plots is not. So let’s start with conflict in general.

Your protagonist (let’s call her “she” for this discussion) has a concrete physical goal she must attain or she will die a literal or figurative death, cease to be the person she wants to be.

Your antagonist (let’s call him “he” for this discussion) has a concrete physical goal he must attain or he will die a literal or figurative death, cease to be the person he wants to be.

The pursuit of these goals brings your protagonist and antagonist into direct conflict because neither can achieve his or her goal without blocking and thus defeating the other.

That blocking and reblocking each other makes the tension rise as each has to fight harder and stronger to win, culminating in a satisfying conclusion in which one completely defeats the other, destroying the loser either literally or figuratively, and giving the reader catharsis after the intense build of the plot.

And then there’s the romance plot (not conflict, we’ll get to that next):

The romance plot has a protagonist and an antagonist (or vice versa) who are drawn together and who, during the course of their story, move through the physical and emotional stages of falling in love, foreshadowing that their love is not just infatuation but is in fact, a deep, true, mature love that will last through time. Over the course of the story, they change as people so they can connect, learning to compromise and forming a bond at the end that will keep them together, safe and supportive of each other, forever.

Now comes the hard part, taking the romance plot and giving it conflict, because the two plots are antithetical to each other. That is, a good conflict has the protagonist destroying the antagonist completely (or vice versa). A good romance plot ends in compromise with both protagonist and antagonist safe, happy, and bonded. Trying to navigate the space in between causes most of the problems in romance writing, including the big two, the Big Misunderstanding and the Soft Climax. The Big Misunderstanding happens when the conflict between the two lovers is a mistake (“Oh, she’s your sister? And I was so jealous!”) so it can be solved by one honest conversation. The Big Misunderstanding is a Huge Mistake in writing romance because it means that the lovers have lousy communication skills and that one or both of them is dumb as a rock, neither of which bodes well for long term relationship success. The Soft Climax is exactly what all of you with dirty minds is thinking: there’s no big payoff at the end because there’s no absolute defeat and victory. It’s the reason romance writing often gets slammed as having lousy plotting; it’s not the plotting, it’s the weak endings (especially the weak endings that are followed by epilogues that shows the hero and heroine have reproduced, thereby cementing their love because everybody knows that children make a relationship easier and are a true indicator of mature love, and oh my god, don’t ever do that).

So the problem becomes how to get the lovers’ growth and compromise in a story with a satisfying climax. I have two suggestions, although there are probably other solutions.

1. Marry the romance plot to a conflict plot that has the big climax, defeating a Big Bad. Don’t run the plots parallel to each other, interweave them so that the romance fuels the conflict plot, and the conflict plot fuels the romance. That is, make the romance something that complicates life for the antagonist, making it harder for him to reach his goals. Then make the backlash from the antagonist something that endangers the romance, creating stress which spurs adrenalin which makes it easier for people to fall in love. So the love story drives the conflict story, and the conflict story drives the love story and you can’t separate the two of them. Almost all of romantic suspense takes this approach, although some are more successful than others at integrating the two plots. How to Steal a Milion is a romance with a caper subplot, but Red is a suspense plot with a romantic subplot. That is, the romance between Nicole and Simon in How to Steal A Million is primary, complicated and driven by their attempts to steal the statue, but the romance between Sarah and Frank in Red is a complication in the main plot to bring down the mastermind behind the killings. Both stories need both plots; the emphasis of the story determines which plot will be the main plot and which will be the complication. Fairly often in this kind of plot, the two are almost equal in importance. It doesn’t matter, the key is that you get both the compromise and bonding of the love story with the catharsis of total victory and defeat in climax of the conflict plot.

OR

2. Merge the conflict plot and the romance plot by making the total defeat of one of the lovers a victory for both. The gold standard in this one is Moonstruck, one of the most brilliant romance plots ever written. Our protagonist is Loretta, a practical woman whose goal is a safe secure life with a man she understands completely but does not love, Johnny. Our antagonist is Ronny, Johnny’s brother, a bitter and broken man who meets Loretta when she comes to tell him that she’s marrying his brother, has a screaming argument with her, and is transformed in the moment to a man desperately in love. Loretta’s goal is a safe life with Johnny and she’s sticking to it; Ronny’s goal is a passionate future with Loretta and he’s not giving up. There is no Big Misunderstanding, they each know exactly what’s going on. The conflict comes in that Loretta can’t get the future she wants if she falls in love with Ronny, and Ronny can’t get the future he needs if Loretta stays practical and marries his brother. One of them has to completely defeat the other. In the end, Ronny destroys Loretta entirely, transforming her into a free and passionate woman who is crazy in love with a man who’s crazy in love with her. Because we love Loretta so much, we’re rooting for Ronny to destroy the safe shell she’s built around herself. So we get Loretta emerging from a closet at the end, reborn and happy because she’s lost everything. That’s great romance plotting. It’s also hard as hell to write but hey, nobody forced you to take this gig. (For an example of an absolute failure of this plot, see You’ve Got Mail; I am convinced that Kathleen woke up one morning, realized what Joe had done to her dreams, and smothered him with her pillow.)

If you’re talking about conflict at the scene level, remember that conflict doesn’t mean that every scene is a huge fight. Conflict is a struggle; you can have conflict in a calm, rational discussion about where to have dinner. Since the courtship phase of a romance is all about negotiation, learning to understand each other’s wants, needs, flaws, fears, and joys and then finding a safe ground on which to meet in the middle, your negotiation scenes will have conflict because it’s about two people starting from different places. The scenes you want to avoid are scenes where people just exchange information, the dreaded Chat, or scenes where the characters do something that causes no change in plot or character, like the Great Sex scene where the earth moves but the plot doesn’t. Those are going to be the parts people skip.

Conflict in romance is tricky to bring off, you have to be smart about it, but since it’s inherent in the negotiations people need to make to bond, and since stress is a big adrenalin booster, conflict can intensify the romance and make it more believable while moving the story events along. Embrace the problem; it’ll make your story stronger.

ETA: The conflict we’re talking about is external. External conflict is the only kind of conflict that moves plot. Internal conflict can demonstrate character growth but very rarely causes it. Forget internal conflict for now, think event on the page or screen, not sittin’ and thinkin’.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

January 30, 2014

Sharp Soap: Why I’m An Arrow Fangirl

I’ve been on a writing wonk tear recently. I had two books going at once, and both were blocked, so I threw myself into good TV, trying to find a different way into story and ended up with a third book because I’ve become so fascinated by episodic storytelling. I’ve been taking apart everything I’ve been watching, trying to see how it works or doesn’t work, and there are several series I’ve been particularly fascinated by because of the choices their showrunners make, good and bad. I’ve learned a lot from Sherlock, Life on Mars, and Person of Interest among others, but the show that has reawakened my old zest for storytelling is an over-the-top superhero series that I started watching because I was stuck in a rental house and losing my mind. It took me a couple of episodes to notice what the writers were doing on Arrow, but once I wrapped my mind around it, I realized that there was a lot the show could teach me if I was just open to it. If I had to use one word to describe the showrunners and writers behind Arrow, it would be “fearless.” Also, possibly “drunk,” because these people will go anywhere.

When I was doing my MFA, the most obscene words in my vocabulary were “sentimental” and “melodramatic.” Fiction, I learned, should be cool, controlled, understated, sophisticated. All writers walk a line between over-the-top schmaltz and no-pulse distance, but it seemed to me that while romance writers (for example) often fell into melodrama, literary writers (for example) often wrote stories that sat on the page like ice cubes. Trying to walk that line made writing story really difficult until I had an epiphany while writing Bet Me: I realized that I didn’t want to be cool, that if I fell off that line, I definitely wanted to fall into the hot side: I wanted to embrace the soap and chew the scenery, I wanted to give my readers a ride. Then I hit a very long bad patch where a succession of life trucks hit me, and I lost my way and started second-guessing myself. I was spending so much time worrying about what was smart and believable, I didn’t believe anything I wrote. Watching Arrow reminded me of the key part of “I can do anything”: I really can do anything if I start with a clear vision of what I want and where I’m going, a kind of focused insanity based on a strong protagonist with a strong goal and an equally strong antagonist, and then after that, just go for it, no fear, screw the people who raise their eyebrows. Eyebrow raising is easy, focused anything-goes storytelling is not. The people behind Arrow are nuts, but they know where they’re going. The show is a beautiful example of controlled over-the-top storytelling, a pretty much perfect balance of grounded reality and insane fantasy, all of it intelligent, whacked-out fun, and I am now a complete Arrow fan girl, with extra grateful squee for the writers who reminded me of why I decided write fiction in the first place.

So here’s what I’ve learned studying Arrow.

WARNING: The rest of this post is full of spoilers. No, really, MAJOR spoilers. Don’t whine later that I didn’t tell you. MAJOR SPOILERS.

Adapting a comic book character’s story for a general audience isn’t easy, especially if that character has been around for seventy-three years, been retconned several times, and has interacted with a galaxy of other characters, many of whom have superpowers. The sheer weight of the source material can smother storytelling (not to mention the whole “willing suspension of disbelief” thing), but the people behind Arrow have averted that by making some very smart choices.

1. They centered their story on a strong protagonist and then grounded him in reality (or at least possibility).

If you’re writing a comic book character, you start over-the-top, but Arrow’s Oliver is a human being, not a superhero; he’s just a rich playboy who does a lot of pull-ups and then goes out and defeats bad guys with a bow and arrow. How is this possible? Oliver gets shipwrecked on an island thanks to his father’s secret career as a maniac, and then gets put through hell by a variety of Really Bad People which turns him into the beta version of the Terminator. I have to admit, the flashbacks to the island leave me cold, but they do explain why Oliver can do so many super-heroic things as a mere human: five years of torture, combat training, and new information coming out of nowhere to blindside him have have taught him to cope quickly with reversal and then put an arrow in it. Anybody coming into Arrow should realize that this is fantasy TV, but because the protagonist is grounded in reality (or at least possibility), the events of the story are grounded, too, which is good because the plots feature things like an earthquake machine and John Barrowman. If you’re bringing the crazy in the rest of the story, make your protagonist the calm, (relatively) stable, believable center that everything else swirls around. Stephen Amell gets a lot of credit here; he’s done amazing things playing a dimwit playboy, a superhero, and a superhero pretending to be a dimwit playboy. (Also, the abs.)

2. They made their protagonist vulnerable by surrounding him with people he cares about.

The big problem with a powerful protagonist is that he’s powerful. That is, Oliver is not an Ordinary Guy hero (that would be Barry Allen); he’s a Prince, immensely wealthy, immensely charming and immensely good-looking. When you start with a Prince instead of the Ordinary Guy, you have to do something to make him vulnerable. (You may have noticed I’m hipped on character vulnerability lately. Hey, it’s crucial, okay?) So another smart thing the Arrow people did was give Oliver family and friends that are important to him. (And again, credit goes to a cast who have really inhabited these characters not only with gusto, but with a complete lack of fear.

For the family, they borrowed heavily from Hamlet in the beginning and then let go of that trope, making the stepfather a great guy and giving Oliver’s mom, Moira, a back story that the Greeks would have called too much drama. Moira has enough nervous energy to power an earthquake machine and enough secrets to keep her nervous for a long time; it’s not every mom who hires thugs to torture her son because she loves him, gets sent to prison because the entire town hates her (well, she did help kill over five hundred of them), gets acquitted through nefarious means, and then decides to run for mayor. The last I saw of her, I think she was planning to off her obstetrician. It takes guts to write somebody like Moira–when she agreed to run for mayor, I laughed out loud–but by god, you can’t take your eyes off the woman.

Then there’s Thea, the bratty little sister, who has arced through a season and a half into a strong, savvy woman who runs both her own nightclub and her boyfriend, Roy, (who used to be an adventurer until he took an arrow in the knee from Oliver; I laughed, but then I’m a horrible person). Roy was just a thug in a hoodie until he had a couple of life-changing experiences and an injection of super-juice, and now he has crazy eyes and is hanging out in the bat cave, suiting up as the Red Arrow (I’m guessing). That means Thea is the daughter of two whack-jobs and the lover of another and at the moment has no idea of either; foreshadowing and expectation: it’s a good thing. This addition of crazy family in peril does two things: It makes Oliver more vulnerable and it adds Soap: seething emotional conflict that is played out in event, not just people emoting, although they do a lot of that, too.

Then the Arrow people left the source material again and gave Oliver a bodyguard named Diggle who learns his secret and becomes his partner with a huge, soapy plot line of his own (dead brother, crush on sister-in-law, still in love with ex-wife, vendetta against a classic comic book bad guy). I really admire writers who say, “So what if he’s a supporting character; let’s give this guy enough story to make his own novel.” (Reminds me of that great writing advice: “Give everybody the best lines.”)

And then, of course, there’s Felicity, the IT girl who wouldn’t know angst if it bit her on the butt the costume department has been showcasing lately. Oliver and Digg get the tortured back story; Felicity gets chipper exasperation and no qualms about saying, “Wait a minute. You’re being dumb.” It’s a team of three equals instead of Oliver and his sidekicks, and that makes them even more important to him, which makes him even more vulnerable. Adding Crazy-Eyes Roy to the team is not going to make him any more secure, either. (Although I’m a little worried about it because the Oliver-Diggle-Felicity trio is the heart of this show. So part of me is saying, “Don’t screw with success” and the other part of me is saying, “And this is how you carefully thought yourself into writer’s block, you dummy. Take the risk.” I talk to myself a lot.)

3. They gave the protagonist a series of antagonists strong enough to shape his course.

So the writers took an iconic character, gave him a soapy family and a strong secret team, and grounded it all in reality or at least possibility. Then, thank god, they deliberately lost their collective grip. If they’d left Arrow in that quasi-reality, it would probably still be a good series, but they’d have been missing that comic book POW that’s pretty much the whole point of adapting super-hero stories. So they did the smartest thing anybody telling this kind of story can do: they put in magnificent antagonists, antagonists who cackle with evil glee, insane sons of bitches with scores to settle and cities to level. When your protagonist puts on a hood at night and goes around the city shooting bad guys with arrows, the bad guys need to be hood-and-arrow worthy. One of my favorites is The Count, mainly because Seth Gabel is the kind of actor who chews the scenery but uses a napkin (he knows what he’s eating but that doesn’t mean he’s going to be a pig about it), but the best of the Bad Guys is John Barrowman’s Malcolm Merlin, the man who sabotaged Oliver’s dad’s boat (which killed Oliver’s dad and started his five-year finishing school on the island), impregnated Oliver’s mother (and wait’ll Oliver’s sister finds out about that), turned Oliver’s best friend against him and then (accidentally) killed him (extra points since the guy was Malcolm’s son), and built the earthquake machine which leveled a good chunk of Oliver’s city along with a good chunk of Oliver’s fortune. Then Malcolm died, except he didn’t, and now he’s back, smiling at Moira with dark irony even as she tips off a secret cult of assassins that he’s in town. Never mind how Moira knows a secret cult of assassins; that bitch has a back story that makes Maleficent look like a 7-11 clerk. Any episode that has Moira meeting Malcolm in a dark parking lot is a good episode: Susanna Thompson and John Barrowman practically quiver with glee as they snarl at each other, great foils to Oliver’s steadfast nobility. Also, a big round of applause for bringing in Amanda Waller to recruit the Bronze Tiger for the Suicide Squad. That can only lead to good things, story wise.

4. They know that great story is fluid and alive, so they abandon anything that isn’t working, they keep the turning points and the reversals coming, and they don’t save anything for later.

One of things that’s most inspiring about this show is how fast and fluid the story planning seems to be. The writers seem to recognize what any smart novelist knows: a series, like a novel, is a marathon, not a sprint, and in the long haul, as you write, stuff happens creatively that you have to pay attention to. If you want to make the story gods laugh, start with an outline. If you want to kill your story, stick with the outline while the story that’s trying to breathe beneath it suffocates. The Arrow writers were playing fast and loose with the canon even before the series started, but the way they’ve paid attention to what’s working in the story and what isn’t is brilliant. Last season’s romance between Diggle and his sister-in-law wasn’t working even though both characters were well-rounded and sympathetic; it was just too complicated with the dead brother in between them. This season, Digg’s not hanging out with the sister-in-law any more; when Oliver asks why, Digg says, “It was too complicated with my dead brother between us.” There’s such smart simplicity to a story that tells the truth and moves on.

Even when they’ve got story lines that are working (which is most of the time) they revise and upend to keep things fresh. Oliver’s immense wealth was making things too easy for him, so Malcolm Merlin destroyed half the city and took Oliver’s net worth with him; Oliver is still a long way from poor, but now he has to put up with a bitchy business partner named Isabel and a city that hates his family. (Really, Moira, you think they’re going to vote for you for mayor?) Oliver finds out Sarah is alive back on the island and barely has time to celebrate before he fails to save Shado. Oliver decides to be a good guy and not kill anybody any more only to be forced to kill to save Felicity. Every time Oliver takes two steps forward, the writers hit him with something that knocks him back a step-and-a-half. That surprise and reversal aren’t just keeping Oliver on his toes, they’re keeping the viewer paying attention, too, and the Girls in my Basement saying, “Do that, do that.”

And finally, the Arrow people understand that story should not be rationed, that keeping the things moving is what makes story great, so they cram as much action and emotion as possible into every week; one episode of Arrow would make six episodes of Agents of SHIELD and an entire season of The Mentalist. Also they are not one-note writers: if you’re not enjoying the episode, wait five minutes and it’ll become a different show altogether (see Esther Inglis-Arkells’s essay, “Arrow Splits Itself Into Four Fantastic (and Nostalgic) Genres.”) Because all the plot lines are linked to the protagonist, they’re integrated, and yet every episode is a plot fruitcake, dense and varied and a solid whole. (And yes, full of nuts.)

5. They integrate their romance subplots into the main plots (mostly).

I’ve done two posts on aspects of the Oliver-Felicity relationship because the fan reaction has been so intense, so it’s probably clear that I’m a Felicity ‘shipper, but I’m an even bigger fan of the way the show integrates its romances into the main plots of the episodes. Oliver has had one-night stands with Laurel and Isabel, whirlwind affairs with Helena and McKenna, and an extremely tense Survivor affair with Shado on the island, and only one of these relationships was separate from the main plot. In fact, one of the reasons Oliver crashes and burns so often is because of the way the romances are part of the main plots: He has to shoot Helena, McKenna gets hurt in the cross-fire and moves to another city to recuperate, Isabel comes on to him only because she’s trying to take over his company and possibly because she’s a villain, and Shado gets executed by an antagonist trying to force Oliver to tell him something. At this point, a character is taking her life in her hands if she agrees to have coffee with him. That may be because Oliver’s entire life is running his company and fighting crime so that’s the only way he meets women, but it also keeps the romances on point and under pressure.

The one place they’re failing, I think, is in not picking a lane for a serious love interest so the show can stop squandering real estate on which-woman-will-it-be scenes. Canon says that the Green Arrow’s great love is the Black Canary, Laurel Lance, but in this show, Laurel has not yet put on the fishnets although her surprisingly-back-from-the-dead sister has. Instead she’s now spiraling into alcoholism and prescription drug abuse while flirting with a politician she rightly suspects is a murderous whack job. (He’s the other candidate running for mayor. Starling City must be in New Jersey.) I’m hoping Laurel meets somebody nice in rehab after Oliver & Co. off the politician because she’s not working as the standard she’s-really-beautiful-and-sexy-and-perfect-so-Ollie-must-love her romantic interest, in part because she’s also the only love interest so far whose story is not integrated into the main plot, so her downward spiral is the story equivalent of your annoying sister who stands in front of the TV so you can’t watch your show.

In the opposite corner we have Felicity, who is not “The Girl” but a full non-romantic player in the story: Felicity has hacked every organization that has an internet presence, gone undercover to cheat at cards in a crooked casino, jumped out of an airplane (and thrown up immediately afterward), and swung through the air on a rope with Oliver three times, which has to be a record for any love interest not named Jane. The writers haven’t used Felicity to tack on a romantic subplot to round out Oliver, they’ve made Felicity and Oliver’s crime-fighting partnership one of the gears that moves the main plots, which is, I think, one of the reasons so many viewers are rooting for her: a love story with Felicity would keep the central stories moving, not distract from them. Add to that the actors playing Oliver and Felicity have remarkable screen chemistry, and that the introduction of Felicity in the third episode saved Oliver from being a boring Grim Bastard all the time, and it’s hard not to start carving “Ollie and Felicity 4 Ever” into your TV cabinet. The first writing wonk thing I did on this show was deconstruct that relationship; if I can set-up a romance on the page the way they’ve done this one, I’ll know I’m back in the game.

6. They know exactly what they’re writing, and they’re embracing that genre with enthusiasm and creativity, making every episode fun to watch.

I think that story enthusiasm is something writers often forget, especially over the long haul. It’s too easy to get trapped in an outline, to concentrate on what happens next without factoring in why the reader will care about what happens next, why the story is just fun/exciting/enthralling to read. We get caught up in parsing out information and forget that unless that information comes wrapped in emotion and action, played out by people we love and hate struggling on the page or screen, unless there are moments that make us sit up and say, “YES!” (or “NO!”), none of that information will matter. Even if the story is tragic, heartbreaking, awful, it has to be fun at a visceral level.

The Arrow writers started with viscera because they started with a comic book super hero, and the temptation to try to be more sophisticated than the source material must have been strong. They have made the stories more sophisticated in execution, but at heart, each episode comes at you like a good comic book page, big visual images that explode across scenes. Oliver shoots arrows that blow things up, that disconnect laser beams, and that disarm bombers, and I can’t be the only person who keeps hoping that he will someday shoot that boxing glove arrow from the comics. Thea gets high and wrecks her car spectacularly, chases down the thug who steals her vintage purse and then kisses him because he’s really cute and tortured and future super-hero material. Digg tracks down his brother’s assassin, breaks into a Russian prison to free his ex-wife, and takes a bullet trying to stop a bomber at a crowded rally. Oliver puts an insane drug pusher in an asylum, then puts him in an asylum again, then puts three arrows in him when the bastard is dumb enough to kidnap Felicity. Moira plots to assassinate Malcolm, then kills her co-conspirator when the assassination goes wrong, then sits in her limousine and weeps over the blood on her hands, Lady Macbeth in a Mercedes Benz. Any one of those things could be a comic book page, all lurid color and hectic movement. That comic book sensibility extends to their enthusiasm for playing fast and loose with convention to get to the juice in their stories. It’s the reason Malcolm isn’t dead (do not give up John Barrowman if you want your scenery chewed), the reason Oliver didn’t save the city last season (a Perfect Hero Who Always Saves the Day is boring and doesn’t change), the reason Sarah came back from the dead to make a terrific Black Canary wrapped in hostility, regret, and fishnet, and Perfect Good Girl Laurel is now Addict Laurel Who Is Pushing Her Luck With An Insane Criminal Mastermind as she drunkenly suggests that Oliver fire Felicity and hire her instead, foreshadowing what I really, really, really, really hope is a slide into villainy, making all of that icy selfishness pay off.

Above all the Arrow writers have embraced the fun, the kind of fun I was having when Oliver yelled at Felicity and I thought, You’re jealous, Oliver, you dimwit, apologize, and then Oliver apologized, and Felicity said, “Does this mean I have a chance . . .” (Felicity, damn it, don’t blow this) “. . . at Employee of the Month?” (Oliver, you jerk, tell her she’s your partner!) and Oliver said, “You’re not an employee, you’re my partner,” and there was some serious eye action and that firm hand on the shoulder, and then they went back to work, and I had to go get a Diet Coke to recover. Fun is all those things that engage reader/viewer emotion, that make us lean forward in our seats, saying, “Oh. My. God,” yelling at the screen because people are doing the wrong thing, because we can’t believe the story is actually going there (Moira’s going to be mayor of Starling City, you know she is), waiting impatiently for what happens next. That kind of fun in story is what makes writing story fun, damn it. How did I forget that?

It’s tempting to describe this show as a guilty pleasure, dumb TV, but that’s wrong. Arrow is smart TV, skilled storytelling, as sophisticated in its structure as it is simple in its emotional hooks. It started strong, and it’s getting stronger because the writers have embraced the crazy while grounding the story in reality, keeping a firm grip on the things that make the story work, especially comic book Good vs Evil, where Good is a conflicted angst-ridden hero with an All-My-Children-From-Hell family and a secret team made up of another equally strong hero and a stealth love interest whose perkiest attribute is her brain, and Evil is John Barrowman.

And that’s why I’m an Arrow fangirl.

January 29, 2014

Lani Has A New Book Out!

Our Lani, aka Lucy March, has a new Nodaway Falls book out!

Beautiful, screwed-up Stacy Easter is back and in magical trouble in Lucy March’s follow-up to A Little Night Magic.

“Great writing and characterization flesh out a unique, compelling plot that keeps readers intrigued and emotionally engaged. Touching, sexy and enchanting.” – Kirkus

And here’s your Amazon link.

Questionable: Surprises in the First Draft

Roben wrote:

My question: If in the middle of writing a contemporary romance a secondary character takes on an entirely different demeanor than you intended, and he becomes larger than life, the tone darkens and switches to what could be romantic suspense, do you toss that character out of your relationship/love story or do you go with it and expand his character and go back and foreshadow?

Although I never follow this advice, I really do believe you don’t change anything in a first draft until the draft is done and you can see the shape of the whole story. I think the smartest thing to do is follow the Girls to the end and then step back and see what you have. But you’re right in that a change in tone breaks the promise made to the reader at the beginning of the book, so in the rewrite you’re going to have to pick a lane.

The key is going to be what kind of story it is at the end, what happens in the climax. The end of the story determines everything else in it. You can’t have a lighthearted comedy where the dog dies in the end. You can’t do a slapstick ending to a dark plot. (That actually happened to a very good movie, The January Man, a story about a serial killer and the serious hunt to capture him that ended with Kevin Kline rolling down the several flights of stairs with the killer and making wisecracks the entire time. It was awful.) So at the end of the first draft, look back and see what you ended up with, and then see how that outlier character fits in. If he’s a betrayal of the climax, you might be better cutting him or at least making him lighter. But if he’s the match for the climax and the beginning just starts too light, rewrite the beginning. What you’re looking for is unity, that sense the story is all one piece, all the smaller pieces locking together and matching to make a whole.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

January 28, 2014

Questionable: Multiple POVs

K M Fawcett asked:

I’d love some insight on writing a series of books. Especially POVs in them. I’m on Book 3 now of my sci-fi/ fantasy romance and this is the 3rd couple I’m writing. However, couples from the first 2 books are intertwined in the story as some are related to each other. I want to give them some POV scenes too but not sure if that takes away from the main romance. I’m not sure how to handle writing it. Would that other couple have to be a sub plot that runs through the story? Do I only keep it in this hero/heroine’s POV? I guess the question is how best to handle multiple POVs in a series. Also perhaps how much back story is appropriate to include so that new readers can follow along and old readers don’t get bored. Thanks!

POV is like salt; it’s crucial but should be used sparingly. I did a book with seven POVs once and it’s still the coldest book I’ve ever written for one obvious reason: the more POV characters you have, the less time you spend in the protagonist’s head. The less time you spend in the protagonist’s head, the less time you have to attach to him or her, the less involved you are in his or her story, and the more distance you’ve created between the reader and him or her.

So when deciding how many POVs you want in a story, my rule of thumb is “as few as possible as needed to tell the story.” One POV is great. If you’re writing a romance, convention says you should have two, the heroine and hero (which is not always the same as protagonist and antagonist). Sometimes giving the antagonist a POV is good idea; it’s what saved The Unfortunate Miss Fortunes (Xan was added in very late rewrites) and I think Bill’s POV was crucial in Crazy for You. Other times, it’s a disaster; most mysteries would be ruined with an antagonist POV.

Once you get past main character POVs, you need to ask yourself exactly what the story is getting with extra POVs. I maintain that Rachel’s POV was important in Welcome to Temptation, but there are readers who would happily have done without her view of the story to get more Sophie and Phin. Lately, I’m happy with the just hero/heroine (not protagonist/antagonist) POVs; more than that seems to defuse the story too much even though the limited POV narrows my options for world-building. However, I’ve also got a work-around because the book I’m most interested in right now is an episodic novel, a series of short stories, each complete on its own, that combine to make a novel, and I have a dozen POVs in that collection that build that world, while each story has no more than three POVs to bring the reader closer.

So here’s my multiple POV advice:

1. Your best choice is one POV for intimacy and reader involvement.

2. If you’re writing a romance, the convention is for both heroine and hero POV (not always protagonist and antagonist), and you probably need a good reason not to use both. (I’ve done just the heroine’s POV and liked it, but it does make the romance a little lopsided.)

3. If you’re more concerned with building a world than with tight reader identification and emotional involvement in the plot, bringing in a subplot protagonist POV provides another view of the world you’re building while reinforcing the main plot. The more subplots you add with POV protagonists, the clearer the world you’re building grows, and the colder your story gets. So if you’re writing epic fantasy fiction, bring on the POVs. If you’re writing romance, not so much.

4. If you’re writing a multi-story series (short stories, novellas, novels, whatever), treat each story as its own unit of narrative, and stick to one, two, or three POVs for each story, letting the separate stories taken together do the world-building and use each individual story to create reader identification and emotional involvement.

As to how much back story you include about previous books, my advice is none. Treat each novel as a stand-alone and handle the back story the way you’d handle the back story in a stand-alone; that is, provide whatever information the reader needs to understand THIS story in the now of the story, and leave the rest out as unnecessary to the understanding of the story the reader has now. It goes back to Strunk and White’s idea that a book should have no unnecessary information in it in the same way that a machine should have no unnecessary parts or a drawing no unnecessary lines, “necessary” in this case meaning “necessary to this story alone” rather than “necessary to the series.” If your reader likes this story, she’ll go glom the rest; if she doesn’t like this story, adding in stuff that doesn’t move the narrative is not going to make her look for more stories like that. Plus you have the same real estate problem with back story that you have with extra POV: the more pages you spend explaining what happened before the story started, the fewer pages you have to tell the actual story.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.