Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 279

January 27, 2014

Next Sherlock Sunday 5: The Empty Hearse by Mark Gatiss

I’ve been putting the craft topic in the headings of these, but the only thing I could think of this time was “The Dickhead Protagonist” which isn’t really a craft term.

Lots of wonderful stuff in this episode, but sitting smugly in the middle of it is Sherlock, the Rat Bastard, who has evidently lost every iota of humanity Irene beat into him last year. Bring back the riding crop.

January 26, 2014

Sherlock Sunday 4: The Reichenbach Fall by Stephen Thompson (Conflict)

There are several reasons Moriarty’s one of the best antagonist’s of all time. He’s up against one of the great protagonists of all time, he’s a doppelgänger for that protagonist, and–in this version–he’s so insane that he’s more powerful than the protagonist. (There are lines that Sherlock won’t cross that Moriarty can’t even see.) Because of that symbiotic relationship that Moriarty has with Holmes, this plot of transference of guilt is brilliant; Moriarty could and does argue that everything he has done could just as easily be the work of Holmes, and it’s so logical that the entire country buys it. So in a sense, the conflict in this story is over Sherlock’s identity, who’s going to control it, who’s going to profit from it, who’s going to die over it. It isn’t just that Moriarty wants to bring Sherlock down, de-fang him, it’s that he wants to become one with him, so that Sherlock isn’t just fighting for his physical life, he’s fighting for his reputation, his legacy, with a foe who will die to take it from him. Much as Aristophanes theorized that people in love were once the same person, and their search to be re-unified fuels their passion, so Moriarty’s recognition of Sherlock as his opposite number fuels his passionate pursuit and ultimate consumption of him. On a thematic level, it really is brilliant conflict, creating not only great scenes as the plot escalates, but roiling the subtext beneath.

But while the episode does a great job of making me furious at Moriarty and sympathetic with Holmes, forever playing catch-up with a faster foe, and while the conflict is clear and strong and drives the story, the story is also smug in the way it plays its secrets and above all in the way it keeps Watson and the viewer in the dark for what appears to be no reason. (And having seen “The Empty Hearse,” I repeat, “for no reason.”) The best Sherlock episodes leave me enthralled and delighted, the worst leave me disappointed and frustrated. This was one of the latter, even though it was a brilliant concept, brilliantly acted. In the end, I think the concept overwhelmed the human element, shot the central relationship in the knee, and privileged more secrets from the viewer over viewer satisfaction.

But I could be wrong. What do you think?

January 25, 2014

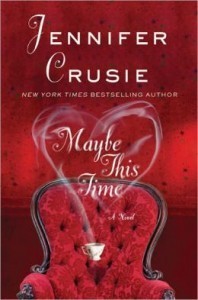

Maybe This Time on Sale for the Nook

I was supposed to put this up yesterday and forgot. Not so good at the promotion, Jenny.

Maybe This Time is 50% off in the Nook store all weekend (today and tomorrow). Was $7.99, now $3.99.

It has ghosts in it. Just so you know.

Cherry Saturday, Jan. 25, 2014

Today is Opposite Day. I thought that was something kids made up to be annoying but no, it’s real.

Questionable: Premise, Central Story Question, Theme

S asked:

‘Premise’. ‘Theme’. And the ‘Central Story Question’. Always hear these terms and blank out. Are they the same thing? How do you use them practically to make your work better? Are they things you think about upfront or try and pick out from a completed rough draft? How do they involve the characters?

1. Not all the same thing.

Premise is the idea you start the story with, often stated as a “What if?” As in:

“What if a retired CIA agent was marked for death and assembled his old team and a new girlfriend to bring down the man who was trying to kill them all?”

Remember, you want your what-if to describe the conflict inherent your story. That is, not “What if a retired CIA agent assembled his own team and brought them out of retirement?” because that could be a story about everybody going to the diner for lunch and telling war stories. Get the antagonist and the conflict in there.

The Central Story Question comes from Michael Hauge, I think. The idea is that you take your protagonist’s name and goal and your antagonist’s name and make a question from them, as in “Will the protagonist defeat the antagonist and get his goal” or . . .

“Will Frank defeat Dunning and save himself and his friends?”

When the reader asks that question, the story begins (so you don’t want to put too much story in front of that realization) and when the reader knows the answer, the story ends (so you don’t want more than a couple of pages after that realization). It’s really a revision tool, an exercise to help you know when to start and end the story more than anything else, although it also useful as a touchstone; that is, when you look at your scenes and subplots, do they help answer the central story question in some way? If not, they can probably go.

Theme is the abstract idea underlying the story, the statement about the human condition that the story makes. It has no moral element; it can be “Crime doesn’t pay” or “Crime does pay.” It’s not a question, and it has no details about the story in it; it’s an abstract idea that powers the narrative.

Teamwork and loyalty will always defeat isolated megalomania.

2. How do you use them practically to make your work better?

They’re not all the same thing, but you use them all the same way, to revise and tighten your work. Both the premise and the central question are touchstones; as you begin to tighten and focus a story in the rewrite, you can keep both or either in mind to cut or tweak scenes that seem weak or that don’t move the story and/or arc character. It’s easy to get lost when writing a novel, so it’s good to stop every now and then ask yourself, “What the hell is this story about anyway?” Premise and central story question are just shorthand ways to keep your plot in line. Theme is a little trickier; you use it in the very last rewrites, to tighten the subtext of your story, especially things like metaphor and motif for unity. Most writers skip that part so they don’t fall victim to theme-mongering. A lot of the time it’s better to just leave theme in the hands of the Girls.

3. Are they things you think about upfront or try and pick out from a completed rough draft?

The way you use premise and the central story question depends on how you work. There are people who start with an outline, so they’d have premise and central story question up front. There are people like me who just start to write as characters talk in their heads and then sort out what the hell is going on in the rewrites. So the answer is “Any way that works for you,” including not worrying about premise and central story question at all. Those things are tools, they’re not necessities like protagonist, antagonist, and conflict.

Theme you do not touch until the last draft or you can get self-conscious and start illustrating theme instead of writing story.

4. How do they involve the characters?

Characters drive story. Story happens because this character was part of this event, and that event changed that character and made him or her do this action, which caused this event, etc. So the premise is the protagonist/main character struggling with the antagonist/other main character. The central story question is that character struggle put into the form of a question. And the theme is what the struggle between the two characters represents, which is why you write the story/struggle and then figure out what it means. It’s okay to think you know what your theme is as long as you shove it to one side when you’re writing the story and then are very open to rethinking it when you’ve reached the final drafts. While I was writing Welcome to Temptation, I thought the theme was going to be about sexual freedom for women. When I finished it, I realized it was about mothers. Go figure.

January 24, 2014

Questionable Fridays

I’ve been thinking. Yes, again.

I won’t be teaching any more after this summer’s McD class ends, and that’ll be good because I absolutely hate grading things. Hate it. The first rule of teaching creative writing is “First, do no harm,” and grading or evaluating too often does harm. I think I mutilated a student last term. Not happy about that. On the other hand, people want honest feedback, not patted on the head. It’s just too damn hard and too damn depressing. So it’s good that I’m getting out.

BUT I love answering questions because questions make me think. Also that’s where real teaching takes place, discussing things. That’s where I do a lot of figuring out what I really think. And when students challenge my answers, that’s even better because that’s when I learn a lot. So questions, yes, I’m going to miss questions. Which is when I thought, “I could do that on Argh.”

Here’s the thing, though: questions only work when they lead to discussions. Which means it would have to be one post per question. I’m good with that because I’m assuming there won’t be that many questions, so I just have to figure out how to get the questions. Which is what this post is about.

Anybody have a question they’d like to talk about? I’m assuming it would be about writing since I know nothing about cars or welding, but I’m open to something else. Also, is this a good idea? Because my usual method of posting is “I find this interesting and I’m sure other people would, too, so here goes.” Needless to say, sometimes those miss, so starting with somebody’s question would at least guarantee that one person would be interested. Probably. I dunno. It’s Friday night and I’m full of brownies and I have a lot of grading ahead of me (oh god) so this could also just be a stalling tactic. Which is another reason it would be good if people did questions/requests.

What do you think?

January 20, 2014

Writing the First Meet Scene: Arrow

Note to Argh Readers:

This isn’t actually a blog post (that’s the next Sherlock Sunday post), it’s an example for a discussion question for the McDaniel students second module in the 522 course, but I needed to embed video and I have to fight with Blackboard to embed TEXT, so I’m doing it here. You are, of course, welcome to dive into the comments. No worries about interfering with teaching; the class will do its stuff on Blackboard.

First meets are crucial in making a romance plot work, and an excellent example of a successful first-meet scene comes from a non-romantic interaction on the TV show, Arrow, done in one minute and two beats. The protagonist, Oliver Queen, is destined to love another woman. The antagonist, Felicity Smoak, is just a one-time character. There is no romantic tension in this scene, no appreciative notice of each other’s physicality, no moments of recognition, no touching. It’s just the billionaire owner of a company asking an IT girl to pull some information off a damaged computer. And yet, this is the scene that launched a thousand ‘shippers and changed Felicity Smoak from a spear carrier to a main character in the series. This is the power of the well-written first meet.

Things to look for in this scene:

Clear Goals: The protagonist, Oliver, enters with a clear goal: get information off a stolen hard drive without alerting anyone that he’s a vigilante. That means he’s come to this place—his own IT department where he has maximum control—and this person—a lowly IT tech who has no power at all to question him—in order to get a concrete, physical goal—information off a computer. No viewer gets confused as to why this scene is happening. I know the “every scene must have a clear goal” feels limiting to writers, but it’s actually freeing: you never have to explain or justify why the characters are doing something, so you can concentrate on how they’re doing it, character in action, which is where all the fun is anyway, especially in a first meet scene.

Character Vulnerability: Oliver’s antagonist is Felicity, an IT girl. The scene tension begins in the first beat when she looks up and sees the owner of her place of employment standing in front of her. Her goal is to keep her job, so all she has to do is shut up and get him the information he needs, but because she’s surprised, she babbles. That means the first beat win goes to Oliver, even though he didn’t intend to catch her off-guard. Still the billionaire just made the IT girl stammer, and that’s the real strength here: these are not two professionals exchanging information, this is a powerful, confident man and a vulnerable, nervous woman, and that vulnerability means that we worry. Even though we know Oliver is a good man, we also know he’s not the most sensitive guy around, and even though we don’t know Felicity at all, she’s so likable and so unprotected here that we lean forward to make sure she’s going to be okay.

Then Oliver smiles at the babble. Since Oliver pretty much never smiles unless he’s pretending to be something he’s not, that real smile says that’s he’s connected, there’s a crack in the tough facade, and now he’s vulnerable. Not a lot, but there’s definitely a crack where before there was just solid granite. And since the person who made that crack is babbling, likable Felicity, readers and viewers sit up a little straighter, aware that something is going on even if the characters don’t see it.

That all happens in thirty-two seconds. No long set up, just “Hi, I’m Oliver Queen,” followed by babbling, followed by viewer/reader anxiety, followed by a smile, followed by viewer/reader awareness.

Character Change: The conflict escalates because nervous Felicity can’t stop being Felicity. It isn’t just that she babbles, although that’s endearing, it’s also that she’s too smart and straightforward not to give him the fish-eye when he gives her a patently ridiculous story about the computer. His position is that it doesn’t matter what he tells her, she’s an IT monkey and she’ll have to do the work, so he doesn’t bother with a better cover story. Her position is that she may be an IT monkey but she has some pride, and while she’ll still say yes and get the information, she’s not going to pretend he’s not lying in his teeth. So she moves from babbling to the fish eye, from somebody we worry about to somebody we cheer for. That’s character arc, change on the page, and it makes the scene dynamic.

Somebody Wins: So the conflict escalates in the second beat because his lie is ridiculous, which causes her exasperation as demonstrated by the head tilt, which makes him smile again, and Felicity wins both the second beat and the scene because the guy with the upper hand has changed and now he sees her not as “IT Girl” but as Felicity. The connection, platonic and professional, is established, but so is . . .

Expectation: The best first meets work because they spark expectation in the reader or viewer. The need to know what happens next, the desire to see these two together again, is the single most important factor in a first meet scene, and this little one-minute scene creates powerful expectation. If you can do that on the first page of a romance novel and then keep building those expectations, you’ve solved half your romance writing problems.

The only You Tube video I could find of this scene (note to self: learn to edit video) has both scenes with Felicity from the third episode of Arrow, so you can stop watching at the one minute mark, the point at which the scene shifts to the two of them looking at a computer screen:

Four other reasons why this one-minute scene is important for romance writers:

1. It demonstrates that a first meet doesn’t have to be about love or sex or romance in any way. Neither Oliver or Felicity at any time in this scene thinks, “Well, hello there.”

2. It shows that it doesn’t matter at all what somebody looks like or is wearing unless the detail is significant in some way. The facts that Felicity is blonde and Oliver has incredible abs are completely irrelevant, but if I were writing this scene in a novel, I’d put that company ID around her neck; it marks her as somebody within his control, his subordinate since he doesn’t need an ID to travel freely through the building.

3. It shows that the elusive element of character chemistry is not delivered with clever banter or great boobs or abs, it’s people reacting as themselves under pressure from each other, changing each other. Felicity is endearing in this scene because her reactions characterize her, but those reactions happen because Oliver underestimates her and then pushes her too far. In the same way, her babbling and head tilt push him out of safe, distant superiority into a recognition of her as an individual, forming a connection that isolated Oliver neither needs or wants, even at this minimal level. (Reluctant chemistry is the best kind because it shows how powerful even a small connection is.) This is why the cute-meet scene can work really well sometimes and fail utterly other times. It’s not about the cute, not about how they look or how snappy their dialogue is, it’s about how the characters surprise each other into vulnerability, about how they react to those surprises, about how they transform each other even if it’s only slightly. Chemistry isn’t about sex, it’s about impact.

4. It shows that scene length is no indicator of importance. This scene could have been four times as long and would probably have had one-quarter of the impact because part of its power is that it takes one minute to change from Billionaire Company Owner vs. IT Girl to Oliver vs. Felicity. The fact that at the end, he’s not thinking, “This woman will become my partner in fighting evil,” doesn’t matter. What matters is the impact they have on each other in such a short time and the desire that creates in the reader to see them interact again.

So how do you blow a first meet scene? Make the characters invulnerable.

Vulnerability is always the key to creating relationships; without vulnerability you have two hard shiny surfaces that can’t attach. The following Oliver/Laurel scene is their first meet in the series, although they have a prior history with each other. That prior history is irrelevant in this discussion because “first meet” also means the first time the reader/viewer meets the relationship, so this is the viewer’s introduction to the great love story of Oliver’s life. But Oliver is detached because that’s Oliver’s go-to coping mechanism (granite, remember); the fact that he’s genuinely contrite is obscured by his distance. Laurel is distant because she’s been hurt so badly and because she’s so angry, but all that shows in this scene is the anger. Which means this is a cold, hostile woman berating a cold, guarded man in a scene in which neither of them changes because neither of them shows enough vulnerability to allow a change. That means that the viewer is given nothing to build future expectations on and in fact, actively hopes they never meet again because these people are unpleasant to watch: two hard, shiny surfaces who make each other colder by their proximity.

Small wonder that when Felicity started to stammer two episodes after this and Oliver smiled, viewers looking for a relationship for him said, “Oh, THERE it is,” and settled in for the long haul in spite of the show’s clear intentions for Laurel as Oliver’s romantic lead. And I do mean, long haul. Thirty episodes later, the Oliver-Felicity non-romance has evolved to this:

So in thirty episodes, the relationship has escalated to standing really close and a shoulder clasp. But look again because the changes are huge, changes that can be easily seen because this scene is an echo of that first meet, this time reversing the dynamic. This time Oliver’s the vulnerable party; he doesn’t babble, but he does address his apology to his quiver, a gawky move the complete opposite of his assumption of power in the first meet. He’s standing and Felicity’s sitting at a computer, the same physical dynamic as that first scene, and he’s asking for something again, but it’s forgiveness this time, emotional connection, and he’s shifting uncertainly on his feet, not standing rock solid and confident. He even bites his lip at one point, and his voice goes up from tension in his attempt at platonic cheer (“Barry’s gonna wake up”). Meanwhile, Felicity is still and distant, holding all the power because, as he’s forced to tell her, he needs her. So on the surface, it’s just a hand on a shoulder and an admission of partnership, but it’s also a huge relationship arc, powerful not just because it’s a good scene but because of the expectations set up in that first meet.

All of which is to say, first meet scenes are crucial to making a romance plot work.

(It should be noted that Laurel is still supposed to be Oliver’s One True Love. I have no idea what show the people who keep saying that are watching, but I don’t think it’s this one.)

Next Sherlock Sunday: The Reichenbach Fall by Stephen Thompson

We talked about beginnings, now let’s talk about endings, especially endings that aren’t cliffhangers.

Also Amazon Instant is streaming the first episode of Season Three now, so we can keep the schedule we’ve got. YAY!

January 19, 2014

Sherlock Sunday 3: A Scandal in Belgravia by Steven Moffat (Motif and Metaphor)

Every time I watch this, I’m astounded all over again at how beautifully this is constructed. (It’s also beautifully directed and acted, but let’s stick to writing.) Rewatching it this time, I was struck by how damn funny the first half is, how light and snarky the dialog and plot are. And then it grows darker, heartbreaking things happen, there’s a magnificent climax and then . . . This is SUCH A GOOD STORY. We could talk about the doppelgänger antagonist again, about writing relationships and not just romantic ones, about characterization and arc, but one of the things this story is especially brilliant at is metaphor, the meaning in the subtext. Metaphor and its stepbrother, motif, sound too grad-school to be any fun, and they too often become heavy-weight story-killers, but handled deftly they can add layers to a story, set up echoes, and generally pull everything together into a unified whole. And Steven Moffat is nothing if not deft. So lets talk about motif and metaphor and the woman who beat Sherlock Holmes.

Motif is easy: it’s anything that’s repeated within a narrative. The shark music in Jaws is a motif; the color red is a motif in The Sixth Sense. Metaphor is almost as easy: it’s a concrete thing that represents an abstract idea. Both metaphor and motif have power, but a metaphor used as a motif is double-barreled subtext. “A Scandal in Bohemia” is studded with metaphoric motifs.

. . . and that’s where I stopped when I was drafting this post and never got back to it, SO I’m putting this up so I can go to the grocery before the snow hits again, and then I’ll come back and talk about specifics of metaphor and motif in the comments. Feel free to start without me and on any topic. ARGH.

Okay, I’m back, I’m fed, and I love this episode.

The thing I love best about it isn’t motif or metaphor, it’s the cataclysmic character change Sherlock goes through because of the impact of Irene. I know there’s a school of thought that says that Irene isn’t as powerful in Moffat’s version as she is in Doyle’s, but I think she’s more powerful: she transforms Sherlock Holmes through the sheer impact of intelligence and daring. He meets his match and she beats him, both figuratively, putting him on the floor, and psychologically, when she blows open his world, destroying his detachment forever. You can’t get the sacrifice he makes in the next episode without Irene stripping him raw in this episode.

That’s why my favorite moment in this episode is when he apologizes to Molly. Before Irene, he could never have understood what he’d just done to Molly. I love the way his new-found empathy makes John and Lestrade and even Molly gape at him when he says, “I’m sorry” and so clearly means it. And that’s followed by his seeing Irene’s present and knowing she must be dead. His vulnerability is so clear that Mycroft offers him a cigarette, a HUGE gesture between these two very controlled men. (I really wonder what Mama Holmes was like.) At the end, when he defeats Irene, he doesn’t do it cooly; there’s passion in every word he says, even though his voice stays steady. And then, having put her on her knees figuratively, he picks up a sword and rescues her when she’s on her knees literally, which is a demonstration not of her weakness but of her power: He’s risked his life and is killing people to save her even though he’s essentially lazy and doesn’t LIKE people; he has to because she’s that essential to his understanding of how the world should work. He outwits her at the end because she cares for him (thus the solvable password), but she owns him in the end because he can’t walk away and let her die. It’s not a healthy relationship, but it is a powerful one, two cold, distant people who have disdain for the rest of the human race, who defeat each other over and over again and yet are inextricably bound to each other.

As a romance writer, I’m amazed every time I watch this episode. There’s incredible sexual tension here but no sex; this is intellectual intercourse. If the most sensitive and powerful sexual organ in the human body is the brain, these two are having the best sex EVER. I love the way Irene deploys sex as a weapon, I love the way Sherlock turns it on her. I love the way she bombards him with sexually coded texts; I love the way he reads every one and never responds until he learns she’s alive, and then says only, “Happy New Year.” I love the way he babbles when she offers him the cryptogram challenge, I love the way she says, “I was just playing a game,” with the plea in her voice that he believe her, that she cares about him. She’s naked in the first scene with him, but for Irene, that’s battle dress. She’s dressed in the climax in Mycroft’s study with him, but she’s never been more naked than she is at the end, in the same way that Sherlock is naked at the palace and invincible, clothed and stripped raw in Mycroft’s study. Clothes have nothing to do with stripping these two bare; they rip every defense from each other in that scene in Mycroft’s study in a true climax in every sense of the word. It’s some of the most masterful writing I’ve ever seen anywhere. (The actors are amazing, too, but we’re talking writing here.)

And then there are the motifs and metaphors. Metaphor, like theme, can be a real story killer, but the way Moffat uses motif, metaphor, and theme in this is so brilliant it actually lifts the story.

So let’s start with an easy motif: the color red. Red means love, danger, evil, death, and above all passion. Seeing red increases respiration and heartbeat; “seeing red” means being overcome by emotion. So all we see of the person who calls Moriarty at the beginning of this episode is her red fingernails, but we know she’s sexual and dangerous. (A nice note of symmetry: Irene’s first action in this story is to call Moriarty; her last action is to text her good-bye to Sherlock and then hand that phone to her executioner.) Irene puts on red lipstick as battle dress; Sherlock shows up at her door with blood spilled deliberately as an assault, to get him in the door. Sherlock, newly schooled in emotion after his meeting with Irene, recognizes the passionate symbolism in Molly’s gift wrap, then sees the same in the gift Irene has left for him, two women offering him sexual love as a gift. Red is threaded through this episode, reinforcing the subtext of passion and its dangers.

A much more interesting motif is nakedness. Irene is naked a lot in this episode but she’s never vulnerable until the end when she’s fully clothed. Irene’s naked body is a weapon she uses; that’s why she calls it her battle dress. She completely disarms John who asks her to put something on, but it’s not her nudity that confounds Sherlock, it’s that she’s stripped herself bare of clues. And yet he should recognize a kindred spirit: he’s just gone to Buckingham Palace in the nude to defy his brother. Mycroft tells him to put his pants on, John asks Irene to get dressed, but Sherlock and Irene know that clothes are irrelevant because they’re not bound by convention or, oddly enough, by sexual feeling. Sherlock may be sexually cold, but Irene is a human iceberg, using the passions of others to gather information and acquire power.

That by itself is interesting; what raises that motif of nakedness to the level of brilliant metaphor is that by the end of this episode, they have stripped each other bare in a much more powerful way: they’ve understood each other intellectually, they’ve seduced each other by flaunting not only their brains but their common disdain for convention, they’ve each recognized that the other is bound by no limits, and their banter and cross-and-double-cross actions are the intellectual foreplay that sets up the climax where Irene rises above him triumphant and on top until he pins her beneath him, destroying everything she’s done in a kind of little death. And even then, they admire each other: she may be the only person who ever beat him, but he is, in turn, the only person who ever beat her. Sherlock tells her he’s defeated her because she’s sentimental, but in the end he keeps her phone, a slave to sentimentality himself.

And that barely scratches the surface of the subtext in “A Scandal in Belgravia.” Start taking apart the metaphors inherent in dominance and submission in this story. The more you unpack that metaphor, the more you find to unpack. It’s just brilliant use of metaphor and motif.

January 18, 2014

Cherry Saturday: Jan. 18, 2014

Today is A. A. Milne’s Birthday.

“It’s snowing still,” said Eeyore gloomily.

“So it is.”

“And freezing.”

“Is it?”

“Yes,” said Eeyore. “However,” he said, brightening up a little, “we haven’t had an earthquake lately.”