Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 274

March 12, 2014

Toni McGee Causey Wants To Give You Something

Toni has something for you:

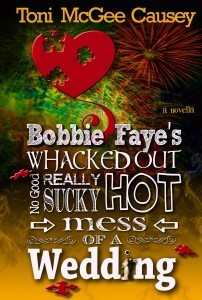

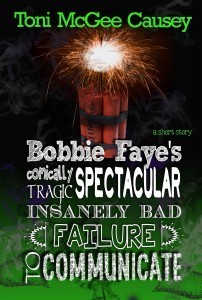

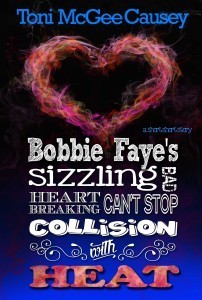

3 Free Bobbie Faye short stories for Toni McGee Causey’s newsletter subscribers. The newsletter will go out early next week with a link to download the pdfs of the three stories (with instructions on how to send it to your Kindle app, or your Nook).

The first one is an incredibly short prequel, the second story’s events take place between books 2 and 3, and the third (a novella), falls a few months after the end of the third book. Not sure who Toni or Bobbie Faye are? Here’s Toni’s brand spanking new website, with excerpts, book links, and her New Orleans photo gallery: http://tonimcgeecausey.com

Want to just go straight to the subscription form? You will be sent an email confirming your subscription–you have to approve that to be on the list. Yes? Go here.

Toni is, of course, one of us here on Argh, so you definitely know who she is.

March 11, 2014

Great Post for Beginning Writers (Well, All Writers, Really)

Charlie Jane Anders has a great post over on io9 for beginning sf writers, but it really applies to all genres.

March 10, 2014

What Must Be Kept

My fake-niece Sarah moved in with me when she was eleven. Sarah’s a writer, so she used to show me her stories, and when I was done reading them, she’d say, “What did you love?” I used to think that was cute; now I think it was genius. “What did you love?” and its older, smarter brother, “What must be kept?” are the most important questions you can ask of your beta readers.

Sometimes what-must-be-kept is obvious. Your main plot stays, along with anything that directly moves it. That’s your third rail: touch that and your book dies in a shower of sparks as many readers throw it against the wall because your story has disappeared into a morass of subplots, and they realize they’re not reading the book they signed on for.

Sometimes it’s less obvious, the small moments of enjoyment that make the story come alive. I learned that in an MFA class when we workshopped a story that had some problems but that also had some beautiful writing in it. When the writer brought it back, she’d fixed the problems, but a lot of the beautiful writing was gone. We hadn’t told her it was beautiful, so she didn’t know to keep it.

You’d think you’d know on your own what to keep, but there’s the other side of the coin: some of the stuff you fall in love with really needs to go. As William Faulkner said, “Kill your darlings;” if you really, really love something, you may have over-estimated its importance in the story, especially if you love it because the writing is sooooooo good. (Ego, get thee behind me.)

Trying to balance “What do you love?” with “Kill your darlings” is even more difficult if you’re trying to save a story, say a novel you’ve been working on for ten years called You Again. I was prepared to dump all 60,000 plus words, but then I started reading through and thought, Wait. Maybe some of this should be kept. Like

“Zelda is very persuasive,” Rose said, grimly. “Which reminds me, stay away from her.”

James leaned against the wall by the french windows and tossed Rose’s present in the air and caught it. Her eyes followed it up and down, so he kept doing it. “I haven’t seen her for eighteen years, Rose. I’m not planning on lunging for her.”

“You won’t have to lunge,” she said. “She’s planning on raping you under the tree Christmas morning. Is that breakable?”

James stopped tossing the present. “Really? Good for Zelda. Why?”

“She’s after something,” Rose said darkly. “Don’t trust her. Can I have that?”

“The Zelda I remember was not good at hiding her motives,” James said. “She was more the slap-you-silly-and-ask questions-later type.”

“She’s changed. You can’t handle her, James. She’s inherited my deviousness. And my breasts.”

“Damn,” James said. “I was hoping to inherit those.” He tried to picture skinny Zelda with Rose’s D cups. “Does she fall over a lot?”

“Don’t be jealous, darling, I’m leaving you my balls,” Rose said.

“I’m not man enough to carry them, Rose,” James said. “I’ll fall over a lot.”

I like that for what it says about James and his aunt, but what I really probably like about it is the banter. If it moves the plot, then it might be a must-be-kept. If it’s just me admiring my own dialogue, it’s a darling-to-be-killed. As it happens, Rose is doing something there that moves the plot, so I can keep it, but it was a close call.

Another pothole in the road to must-be-kept is “But I need to explain this” and its ugly cousin “I need to set this up.” I spent 2400 words on James talking to Angela in his law office, after which I spent another 4000 words on James driving to Rosemore, and all of that was back story, endless back story, back story with some minimally snappy dialogue, but still freaking backstory. Six thousand four hundred words, not one of which moved story. Plus, James isn’t even a lawyer any more. Even I could see that had to go. (No, I’m not showing you 6400 words of wretched back story.)

A third one to look for: “Why is this guy in here?” (Or woman, gender is irrelevant.) I had a defrocked doctor name Liam who was necessary for one crucial scene, so I made him the current, younger lover of Rose. I thought long and hard about cutting him, but that wasn’t going to work because I absolutely needed him for that one scene, so then I thought long and hard about what else he could do in the story to earn his keep, which is when it hit me. Liam had lost his license for dealing prescription drugs, which was useless because there weren’t any drugs in the story. What there was in the story was death: murder and ghosts and an in-the-dead-of-winter setting. So what if Liam had lost his license because he’d helped terminally ill people die with dignity? What if there’d been a little uncertainty as to whether the people had been ready to die with dignity? What if he was cold (it’s winter out there) but honest, a really good doctor missing a piece? That’s a character I want in a murder mystery. Liam stays.

But then there was Nora. I loved Nora. Here, meet Nora:

“Hello, Rose,” Nora Inglethorp said, heading for her hostess. “What in God’s name made you decide to have us all here?” She was smiling, looking much the same as she had the last time Zelda had seen her—dark-haired, red-lipped, almost frighteningly vivid–except for the addition of a good thirty extra pounds, all of which seemed to have settled in her stomach. She kissed Rose on the cheek with an audibly affectionate smack and then took off her coat as she turned to face the rest of the Inglethorps by the fire, and Zelda braced herself for whatever the vipers over by the fire were going to do to her.

“Good Lord, Nora,” Malcolm said, malicious delight on his face. “You look pregnant.”

“Hello, Malcolm,” Nora said. “You look old.”

“Junior Barnes should see you now.” Malcolm snickered. “Some goddess.”

Nora frowned, but Mary said, “What?” Her voice was avid, and she leaned closer to Malcolm, eagerness in every pore, knowing something mean was coming.

Bitch, Zelda thought.

“Don’t you remember?” Malcolm said to Mary. “Junior Barnes called Nora a goddess that one summer. The Aphrodite of Ohio.”

“Oh, right, I remember.” Mary nodded, happy for the first time that evening. She smiled in satisfaction at Nora. “He should see you now, Nora.”

Nora ignored her to frown at Malcolm. “You never told me that. Who said it?”

“Junior Barnes,” Malcolm said, with heavy patience.

“Oh, that loser.” Nora dismissed him with a wave of her hand and turned to Zelda and the drink tray.

“He’s a very fine man,” Malcolm said stiffly.

“He’s a chinless moron.” Nora picked up a martini. “I always thought you hung out with him on the fat friend principle.”

“He wasn’t fat,” Malcolm said.

“No, but he was dumb. You looked like Einstein next to him.” She drank half her martini in one gulp.

“I can’t believe you’ve let yourself get so out of shape,” Mary said, blatantly delighted.

Nora smiled at her sister-in-law, and Zelda thought, Oh, Mary, you dummy, and balanced the tray on her hip as she watched.

“I didn’t let myself get out of shape, Mary. I got hit with menopause. It happens very quickly. You go to bed the Aphrodite of Ohio and you wake up the Venus of Willendorf.” She turned back to Zelda. “Another, please.”

Zelda took a martini off the tray and handed it to her.

“Nora, for heaven’s sake,” Mary said.

“Shut up, Mary,” Nora said. “I’m drinking for two.”

Say good-bye to Nora. She served no function in the text so I sent her to Italy where she’s having a marvelous time. You will not hear from her again.

Which brings us to the distinction between “What do you love?” and “What must be kept?”

In the first rewrite, you keep everything you love, cut everything that’s not moving plot, and fix everything that moves plot but that’s not as good as it could be.

In the second rewrite, you kill any darling that’s not earning its real estate in the plot even if you love it.

And then you give it to your betas and say, “What do you love? What must be kept?” and do it all over again.

March 9, 2014

The First and Second David Jobs: The Recurring Nemesis

Note: The blog broke last night so I didn’t get to revise this and clean it up, but it’s Sunday and it’s getting late so this is going up as is. Apologies for the sloppy work.

“The First and Second David Jobs” are just good storytelling, period, but they’re also great community building because “The First David Job” destroys the community and “The Second David Job” restores it, stronger than before. And all of that happens because the team meets Nate’s nemesis and doppelgänger, James Sterling, aka “The Guy Who Never Loses.”

Oh, Sterling, I do love you.

A nemesis is “the inescapable agent of someone’s or something’s downfall,” a pursuing fury that does not rest until it has defeated its mark. Nate Ford’s nemesis is James Sterling, an insurance investigator who has Nate’s old job and intends to keep it, but there’s more at play than that. Sterling IS Nate, he’s as smart as Nate, as underhanded as Nate, as ruthless as Nate, as fast as Nate. He knows what Nate’s going to do because it’s what he’d do, just as Nate knows him. There’s bitter rivalry there but there’s also healthy respect and not a little admiration. But if they’re so evenly matched, how can Sterling always win?

Because Sterling’s the good guy. Sterling’s the one who plays on the side of law and order while Nate creates chaos. Sterling has the full force of the law behind him, while Nate has Sophie, Hardison, Eliot, and Parker. Sterling still has a reputation to polish, a child to protect, a career to advance. Nate is a drunk with a son he couldn’t save and a career he walked away from. Sterling is the Golden Boy and Nate is the Dark Horse. This is a show about justice being served, and you can’t serve justice by defeating the good guy, so Sterling Always Wins.

On the other hand, it’s hard to root for the guy who holds all the cards. Nate may be the bad guy in Sterling’s world, but in the world of the show, Nate’s the wild card in the justice game, the guy who comes out of nowhere and sweeps the board, righting the wrongs that justice and Sterling cannot fix. So Nate also has to win, which is one of the reasons that the stories get so much more interesting when Sterling shows up.

Another thing that gets more interesting is character. Just by existing, Sterling makes Nate face the truth about himself because Sterling is the perfect foil. Nate tells himself that he not a thief, he’s not a drunk, that he’s just fine, but when he sees Sterling, he can’t escape recognition of how far he’s fallen because he used to be Sterling. It’s not a coincidence that when Nate begins to hallucinate in detox, it’s Sterling he sees taunting him with his failures and his fall. Sterling’s very existence rips aside Nate’s rationalizations, so in a way, Sterling is the best thing that happens to Nate: just by breathing, he drives Nate to face the truth about himself.

Of course, Sterling does a lot more than breathe. He knows Nate’s gone over to the other side, so whenever Nate shows up on his radar, Sterling takes note and pursues. This isn’t good for the team any time, but it’s especially bad when the job the team is doing is complicated, Sophie’s hiding something, Nate’s emotionally involved in the con which blunts his judgment, and worst of all, he’s still drinking heavily. Add to that the rule in the Leverage writer’s room–Sterling Always Wins–and you have all the elements of disaster. Sterling’s appeared in episodes before these and he’s going to come back into the Leverage team’s lives again and again, but this is the job that sets the bar, the job that shows Sterling exactly what he’s up against and shows the team exactly how much trouble they’re in every time he comes into view.

Fun fact: Sterling was written specifically for Mark Sheppard to play.

So what’s the value of a nemesis to a story about community? It’s a unifying element. Each week the team defeats a different antagonist which reinforces their sense of teamwork, and each week they learn a little more about each other which reinforces their sense of family, but the things that help meld them into a group are the things that recur and become a shared language: the brotherly sparring of Hardison and Eliot, the team effort to bring Parker into the land of the reasonably sane (“You’re Alice”), shared goals, shared memories, and a mutual loathing of one guy who pursues them, their leader’s doppelgänger, the guy Parker calls “Evil Nate.” Sterling is great story fodder because he’s a great character, but what he’s best at is uniting the team against him.

“The First David Job” (aired twelfth)

Sterling may be Nate’s nemesis, but he’s not Nate’s antagonist in this episode. This time he’s a minion of Ian Blackpoole, the CEO of the insurance company that refused treatment for Nate’s son. Blackpoole is about to open an art show in “his” wing of a museum, and the centerpiece of his collection in one of two existing maquettes for Michaelangelo’s David. The opening is Nate drunkenly accosting Blackpoole, but a “Two Weeks Earlier” tag takes the narrative back to the original plan. (I HATE those media res openings.)

The Inciting Event

Nate’s drinking is getting worse, so the team stages an intervention, telling him that he doesn’t need rehab, he needs revenge, and then telling him about Blackpoole’s show. This con isn’t about saving someone helpless, it’s about fixing their leader’s past because the demons that torment him are hurting the team.

The team figures out the plan to con Blackpoole out of eight million dollars by selling him a second David, thereby making a fool out of him and destroying his reputation when the statue is found out to be a fake. They put the plan into action, getting Sophie into Blackpoole’s circle as a representative from the Vatican and Eliot in as the expert who will examine the statue to establish it’s authenticity. Nate fakes being drunk to accost Blackpoole and offer him the statue which is being sold by a middle Eastern prince (that would be Hardison) while Hardison and Parker wait in the van. The team is doing great, Nate explaining to Blackpool why he’s brokering the deal–he’s broke, he’s living in his car, etc.–when he’s overheard by the blonde that Eliot has been chatting up. Unfortunately, she’s Nate’s ex-wife Maggie, and his past comes back to kneecap his team again.

The Change of Plans To help Nate make the sale because she feels sorry for him, Maggie volunteers to examine the statue for Blackpool. Since Maggie is an art expert, the story now changes from a con–sell the fake David–to a theft–Parker has to go in and steal the real first David, switching it with the fake, so that the statue that Maggie examines will be real.

As the team scrambles to make the new plan work, Sophy suggests they up the con, switch the real first David they’re going to sell Blackpool after the sale, leaving him with two fakes and a ruined reputation. The team is enthusiastic about it, but Nate takes Sophie into his office and tells her that he know what she sounds like when she’s running a con, telling her “You don’t con us.” Sophie’s more interested in Maggie, wondering how she can work for Blackpoole, the man who let her son die, and Nate, distracted, tells her that Maggie doesn’t know, he never told her. But as she goes out the door, he says under his breath, “There’s that voice again . . .” and the seed is planted that Nate’s past isn’t the only history threatening the team.

Point of No Return: They decide to steal back the first David to destroy Blackpool completely. The story turns again (that’s why they call these “turning points,” folks), this time from a single theft to an elaborate con.

The team goes off and pulls the job exactly as they’d planned except that there’s a hitter named Quinn waiting in the hanger to take Eliot out, goons in suits break into the offices and knock Hardison out, and Sterling is waiting for Parker when she breaks into the van to steal the First David back. The kids are in big trouble because Mom and Dad are trapped by the past.

Crisis: Sterling meets Nate and says, “I know how you think;” his price for giving them Hardison and Parker back will be the second David. When Nate says, honestly, “I don’t have it,” Sterling says, “Of course you do. Just ask yourself, ‘Who came up with the plan to break Ian Blackpoole?’” And light dawns as Nate turns to a guilty Sophie: the entire Blackpoole con has been a set-up for the real con, Sophie conning the team to get the second David, something Sterling can see because he’s not blinded by drink and an affection for Sophie. It’s a devastating last blow in Sterling’s attack. He’s divided and conquered Nate’s team–Eliot’s injured, Parker and Hardison have been captured, and Sophie’s betrayed him–and the story now swings from a triumphant con to a frantic scramble to save two captured team members even as everything they’ve worked for falls apart.

Sophie takes Nate to the Second David, and Nate angrily tells her she’s addicted to theft. “We’re all addicts to our pasts,” she tells him, and then getting to the heart of the problem with the community, tells him: “You still think of us as just criminals. There’s always going to be a part of you that thinks you’re better than us,” forgetting that there’s still a part of her that thinks her needs are more important than the team. But she’s right about one thing: as long as Nate is addicted to and driven by the idea that he’s an honest man, he can’t embrace the team that’s his future and walk away from the bottle.

Nate moves on to the practical problem of getting Hardison and Parker back. Sophie tells him they can’t win because Sterling knows how they think.

“So we think like somebody else,” Nate says and thinks like Parker and Hardison. (Sophie and Parker’s escape from the roof is one of my favorite scenes in the entire series.)

Climax: The team blows up their own home base to destroy the paper trail that Sterling would have used to bring them down–Hardison’s multi-screen “Hey, Sterling, get out of my house”–but Sterling rightfully claims victory: he has the money they scammed from Blackpoole and both Davids which his company had insured. The team’s covers are blown, their faces have been sent to every law enforcement agency in the world, and their base of operations is destroyed. There’s only one smart thing they can do, Sterling tells his henchman, and they’ll do the smart thing because they’re professionals: they’ll scatter, breaking up the team forever. The last scene shows the team walking off in five different directions. Sterling Always Wins.

COMMUNITY STATUS: Destroyed.

Good thing there’s one more episode to go.

The Second David Job (last episode of Season One)

Inciting Event: Sterling is now Vice President at IYS (Insure Your Stuff), but when Blackpool shows him his new office, Nate is sitting in his chair. He tells them, “I’m going to rob the two Davids gallery on opening day,” and then leaves Blackpool laughing and Sterling on guard. (I particularly love this line because he doesn’t say, “I’m going to steal the two Davids,” and for once, Sterling misses the clue.)

Meanwhile, down in the gallery, Sophie, Parker, Hardison, and Eliot are all casing the joint separately, Sophie very nearly running into Maggie. They see each other about the same time that Sterling’s team sees them, and the four of them make a run for it as Nate pulls up a car to help them escape. They end up back at Hardison’s new safe house, arguing and blaming each other until Sophy says, “We’re a mess.” Nate brings them together as they talk about their individual plans for a robbery and then he asks them why they came back when they’d agreed to split up for six months. They all have different reasons–Sophie’s is to hurt their nemesis Sterling–but what they’re facing now is that the robbery is going to be twice as hard as it was before. “Four times,” Nate says and tells them he warned Sterling. Then he tells them that they’re all trying to solve their versions of the crime, adding, “There’s a reason we work together.”

Change of Plans: They agree to get the crew back together, and the story swings from five people planning five different heists to a fragmented crew trying to come together to pull off their last job.

They make their plans which rely on conning Maggie into helping them unaware, but sharp Maggie catches on and they have to read her in on the plan, a new albeit temporary team member, bringing Nate’s past and future together in one place. No wonder he drinks. Nate finally tells Maggie the truth about what happened to their son, and she’s in, but when she hears the plan, she says, “You can’t just make somebody do want you want them to do.” The team unites in their amusement, Hardison saying, “That’s what we do,” and Parker patting her head and saying, “You’re adorable.” The key thing in that scene is that “that’s what we do;” they may be down, but they’re thinking like a family again.

Point of No Return: The story swings from a team trying to con somebody into helping them to a team with a new member going into action.

They scam everybody while Sterling keeps watch, trying to figure out what they’re doing, on top of their every move. Along the way, Parker, Hardison, and Eliot have a come-to-Jesus talk with Sophie about not scamming family–Eliot says, “I was just getting used to be part of a team”–and then they accept Sophie’s non-apology as an apology and move on because it’s show time.

Crisis: Alarms go off as an unknown gas is released into the gallery, and Sterling and Blackpoole and the security team run into gallery to find Nate leaning against the case with the two Davids now obscured by smoke. The story swings from planning to final execution as Nate faces down the man who let his son die and the nemesis who destroyed his team.

Climax: Nate tells Sterling that he can have all the artwork back as long as he ruins Blackpoole. Sterling may know Nate, but Nate knows Sterling: as Sterling says, “You know, your entire plan depended on me being a self-serving, utter bastard.” Still, he agrees, destroying Blackpoole and scoring a promotion for himself because Sterling Always Wins.

Resolution: The team splits up again, but it’s clear that they’re all having second thoughts even as they leave.

COMMUNITY STATUS: Tune In Next Season

The end of the community arc in this first season is a demonstration that the team is so strong it can’t be destroyed. Their leader may be a drunk, their mother figure may have betrayed them, their nemesis may have triumphed, they may be beaten and scattered, but in the end they’ll always come back together, a family tested once again in a crucible and made stronger by adversity.

Next week: “The Beantown Bailout Job” brings them back together after Sophie invites them all to her debut as Maria in “The Sound of Music.” When Parker says, “I didn’t know you could sing,” Sophie says, “Well, not as well as I act,” and still everybody shows up to watch her. That’s family.

March 8, 2014

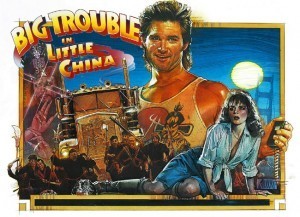

The Movie That Is You

Because I’ve been spending way too much time in my head lately and after that way too much time on io9 (it’s where my brain goes to rest after thinking about story all day), I began to think about the movies I love, which then led to thinking about how my taste in movies defines me, which then led me to think about what I’d choose if somebody put a gun to Milton’s head and told me to pick one movie that represents my taste in story and my worldview. The movie that, if you like it, you will probably like me and I will probably like you. The movie that I would take to a desert island with me and play over and over. That movie.

This is Milton:

And this is my movie:

What’s yours?

Cherry Saturday: Mar. 8, 2014

Today is Be Nasty Day. Except don’t be. Tomorrow is National Panic Day; let’s go with that. We’d be doing that anyway.

March 7, 2014

The Contract with the Reader

Buried in the 300+ comments on the previous Arrow post is a really good discussion on the contract with the reader. We’ve talked about the romance contract here before, but as Pam pointed out, all stories make contracts with the reader/viewer, not just romances.

Here’s my comment on the promise to the reader:

I’ve been thinking about series storytelling (film and books) and the idea that the first page/scene is a promise you make the reader/viewer. I absolutely believe that: the introduction to a story makes a promise to the reader, says this it what this story is going to be about, here are the people to root for, here’s the genre, the mood, the setting, the tone, everything. And then people read/view that promise and decide whether to sign for the story and by extension, the series. If you’re writing a stand-alone novel, that’s fine, you’ve only locked yourself in for that story. But if you’re writing a series, that’s a long-term promise that I think you almost have to shift. Not break, but gradually steer into the direction you’re finding works better if you begin to see a problem. A lot of long-running series in both books and film never break the promise, but they run the risk of going stale, so evolution is important and change is often good. I think the problem comes when the perception is that the promise is broken, that this is not the story the reader/viewer signed on for, that the writer was doing a kind of bait-and-switch. And I think that’s where the assumption that Arrow is about Oliver-Diggle-Felicity comes in, that the promise this show made was that it would primarily be about Oliver Queen fighting crime. As I remember, the pilot had a lot of relationship stuff going on, too, but I read that (my story-goggles) as subplots, the things that would make Oliver’s life more difficult, not the thing the story was about. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that some people may have seen it as a relationship drama, so that when episodes focus on relationship issues like the Clock King episode did, they don’t see a fragmented story that has gone too far and broken the promise, they see exactly what they’d been promised.

I think that’s why, when you’re telling a story, you have to nail the essence of that story on the first page. The books that start with the protagonist staring out the window thinking about her life, or with the author explaining the character’s back story, miss the opportunity to open the door to the reader and say, “Come on in, this is the kind of party this will be,” and establish it firmly in the reader’s mind so that while the reader can still write her part of the story into the white spaces, she can’t say, “No, it’s not about the main plot, it’s about the subplot.”

Then Sarah B replied

I don’t mind if a story I read or watch doesn’t work out like I want, emotionally speaking, as long as I can believe in the direction the creator has taken it. Buffy and Spike are the couple dearest to my heart, but Joss never let them have their happy ending. But I could understand why he wrote the show the way he did, the characters generally stayed true to themselves, and the resolution had an inner logic and truth that fitted with the world he’d created, even if it made me sad. Stephen Moffat also famously does terrible things to beloved characters, and he’s still a brilliant writer . . . .

It’s all about the narrative for me, even if I love F[elicity] and Diggle more than anything else (except maybe the salmon ladder..;) ). When that the story is working, I’ll accept whatever the writers throw at me. I’ve been a Doctor Who fan all my life, and no other show’s writers are more likely to stomp on your heart! Except Joss Whedon, maybe. So, I don’t need to be happy, just convinced.

I love that last line especially:

I don’t need to be happy, just convinced.

I think it’s the double tap of successful stories: establish a clear contract with the reader/viewer and then tell the story so that it makes sense to that reader/viewer in terms of that contract. I hated it when a character I loved died on Person of Interest, but I understood why it happened, it didn’t violate my contract with that story. Beth dying in Little Women ripped my adolescent heart out and fed it to the cat, but it was part of the contract Alcott established. I think a lot of the controversy over Wash’s death in Serenity was really a discussion of a broken contract because it was by no means implausible that one or more of the Firefly team would die horribly in battle, but it was, I think, an unspoken contract for a lot of people that the deaths would mean something. There’s a difference between “This is plausible within this story world” and “This is the story I signed on for,” and I think a lot of Firefly viewers thought they contracted for a story with innate justice.

But the new thing that came up for me was the idea of story focus as part of the contract. One thing romance writers have to do when they first start a novel is to determine if the romance is the main plot, or a subplot that’s almost equal in importance to the main plot. It’s tempting to try to have both, but you really do have to pick a lane or your plot goes all over the place. You can start with the same basic premise and plot, but that plot told as a mystery with a romance subplot will be different from that plot told as a romance with a mystery subplot. You allocate story real estate differently, the aspects of the plot change with the approach. Again, quoting myself (I have no problem with arrogance):

Leverage established from the beginning, I think, that it was first a show about community and then a show about the cons. The two were inextricably linked, but if the focus had been on the cons, they wouldn’t have pursued Nate’s alcoholism at such depth and would instead have used it as a liability and a complication for the cons. Instead, even though Nate has a raging alcohol problem, it doesn’t affect his ability to run the cons. What it does have an impact on is the team, which is why they try to help him. The center of the story is the team, and the team is explored through the cons, not the other way around.

Or take Person of Interest, which was established as an Equalizer/Crime-of-the-Week story in the first season, which then evolved into a Equalizer-against-secret-government-agency story, which then evolved into a Equalizer-against-forces-beyond-your-wildest-dreams story. There are intense personal relationships within that story, but none of them are romances. (I consider Reese/Zoe a team-member-with-benefits because it’s clear that’s how they consider themselves.) The stories evolved, and as they evolved and the danger grew greater, the team established relationships that went bone-deep, we’ll-die-for-each-other levels, but the show always kept the central promise: this team will fight for the helpless against the powerful forces that try to hurt them. The way they’ve defined “helpless” and “powerful forces” changes, but the promise stays the same, this show is about the fight between good and evil, not about relationships. The fight forms the relationships and drives the relationships, the relationships do not drive the fight.

So I’m thinking that that contract with the reader extends to emphasis, too. It’s not enough to say through the events of the first scene in a novel, “This is a romance and a mystery,” you have to establish, “This is a romance with a mystery subplot” or “This is a mystery with a strong romantic subplot.” Because if you don’t establish that, the reader will decide for you. I screwed this up completely in Wild Ride in spite of my readers and my editors pointing out this very problem, and I will not do it again: Making that contract clear is crucial to the success of your story.

Questionable: Pictures and Writing

Deb Blake asked:

I know you’ve talked a lot about your creative process with storyboarding (is that a word?) and collages and such. I don’t tend to use such things, but I’m starting to make Word docs for each novel that include pictures of my protagonists, and other notable stuff (their dogs, cars, motorcycles). Can you talk a little bit about how you create and organize your pictorial “notes”?

I just went back to the draft to this post to reread my answer and realized that I didn’t answer the question Deb asked, I answered the question I thought she asked. So first, here’s the answer to her real question:

I create most of my visual notes by grabbing them off the net, taking pictures with my phone, drawing diagrams by hand or using Curio, and by creating computer collages using Curio, Elements, or Acorn.

I organize my research images, four ways.

I sort them into folders in the book folder on Dropbox.

I combine them into group images in Curio and Acorn.

I put them into VooDoo Pad docs

And I use book boards on Pinterest.

What I thought Deb asked was how I used visuals. I have no idea why I thought that, her question is perfectly clear. But since I answered it . . .

I think the most important thing about using visuals in writing is that it’s a much more natural way to think. Those lines of type are not the way we navigate through the world. We don’t experience things in straight lines and words, we see this and then that over there and then that other thing over there and we see relationships between them and make connections and assumptions that we don’t always verbalize. We observe life, we don’t read it (which is one of the reasons that comic books and film are such great delivery systems for story), and we often use those observations to make patterns and then use those patterns to determine what’s going on, what things mean. So when we’re trying to recreate real life, it makes sense to try to observe the fantasy we’re creating so we can see those connections and patterns.

There are limitless ways to use visuals, but the ones I use most often are:

Story Journals:

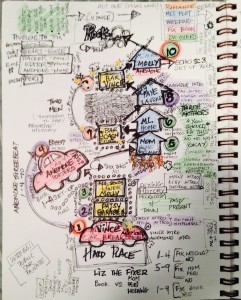

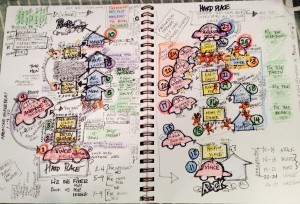

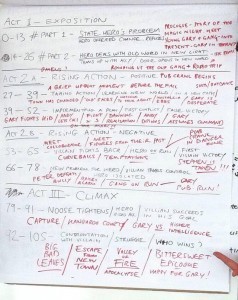

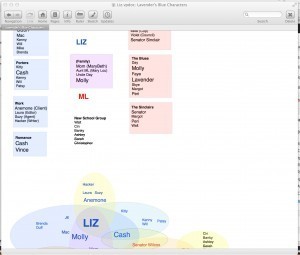

I do a lot of my note taking these days in visual journals. If I want to see all the scenes in an act, I put them on a page in diagrams, starting at the bottom because I want my scenes to rise in tension and because reversing the way I normally see things helps me see everything more clearly. For example, in trying to figure out the patterns in the first part of Lavender’s Blue, I wrote the protagonists for the scenes, starting at the bottom up, trying to place the main plot in the center and subplots off to the side. What I found as I doodled, though, was that I was actually dividing the scenes into spheres. That is, Liz meets some people in public places (yellow squares with lights around them), some in private spaces (blue houses), and some in the mediating space of her car which is both public and private (red cars). At that point I could see patterns in the first act–three mothers in the blue house scenes, the Cash/Vince foil scenes in the bar–and I could see where I was missing things, like Anemone who in this chunk of story only had one scene even though she was a big motivating force. If I wanted her pushing Liz through the plot, I needed more Anemone, so I added some more red in places.

The second act on the right hand page changed when I compared it to the left: I noticed I had another three mothers group, and I realized that the “Fix it, No” thread in Act One had turned into “Fix It, Yes” in Act Two. And I had completely missed the fact that I had three scenes in Vince’s car toward the end, building to the love scene, so I could rewrite those as an escalating series. The diagrams made it easier to divide both acts into scene sequences, too (see notes in lower right hand corners of pages). I could also go back in and doodle the motifs next to the scenes where they were mentioned (pearls, teddybears, T-shirts, etc.) That way I could see if I was repeating them, escalating their importance so I could pay them off in the last act. It’s about here that I start gluing stuff in, which makes the pages a real mess, but that’s okay, this isn’t art, it’s note taking.

And sometimes just screwing around on the page helps solidify ideas. Because neatness doesn’t count on this stuff and because I knew the act was going to end in Liz getting hit with a rock, when I started the first act notes, I doodled “Rock” at the top of the page (the top because I wanted my scene notes to rise in action from the bottom of the page). Then because it’s just doodling, I wrote “Hard Place” at the bottom (ha, amusing myself) and put the car/first scene there, and then realized that was a scene which was a hard place for Liz to be, thanks to her mom and her aunt. When I did Act Two, “Rock” had to go at the bottom, so I wrote “Hard Place” at the top and damn if that last scene isn’t Liz back in her car in a really hard place thanks to her mom and her aunt. Again, that’s something I wouldn’t have noticed if I hadn’t been doodling cars and making dumb visual jokes about Liz being caught between a rock and a hard place

The examples above are in a smooth Bristol journal which will take a lot of abuse–Sharpie doesn’t bleed through this stuff–but you can do this on anything. The key, as in anything visual for writing, is that it’s not artwork, it’s notes. You don’t critique your penmanship when you make notes, so don’t critique your drawing ability or your neatness when you draw notes. (That big grey splotch in the middle is a mistake, not a symbol.)

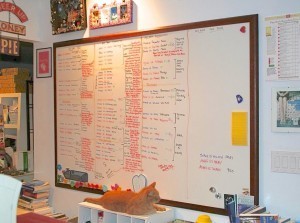

White Boards

Another way to do note diagramming is to do it on a big white board. If you don’t have the wall space, Home Depot has 2′x4′ sheets of whiteboard that are very portable and the perfect size for diagramming an act, a short story, or a novella (okay, you might need two for a novella).

The one below isn’t mine, it’s from the original brainstorming for the movie The World’s End via io9:

Or do the scene diagrams in a graphics program. This one was done in Curio:

Collage

Collage is probably my favorite visual crutch, a place to combine images that evoke the book into a single image that captures the book as a whole. I’ve written about collage a lot before, so here’s the Lavender collage in progress and a link to the blog post that talks about collaging a series and the Three Goddess Chat on collaging. See also Picture This: Brainstorming as Prewriting and Inspiration and the website page with the discussion of my collages.

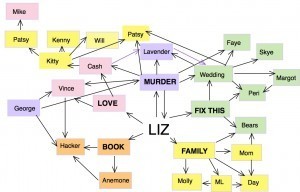

Mind Mapping

Mind mapping is another way to see character relationships, plot and subplot movement, use of motifs, etc. I use Curio software because I’ve had it for years and I like it, but there are any number of programs out there. Even better sometimes is good old pen and paper although it doesn’t give you the luxury of moving things around the way mind mapping software can. I usually end up pasting the finished maps in my journal anyway, just so I can flip to them when I need them.

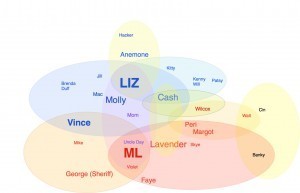

A cousin to the mind map is the character relationship map, a kind of Venn diagram gone mad. Make a list of all your characters and then make a list of the groups they belong to: family, friends, work, school, whatever. Some of your character will be in more that one group and that’s fine. Then write your protagonist’s name large in the middle of blank page with the antagonist’s name large beneath that (leave some space) and the put the groups around the two names, overlapping when names are shared. It takes some jiggering, but when it’s done you can easily see the push and pull of group identities on the different characters. When I did the first one for Lavender’s Blue, I realized that I had aligned everyone with the protagonist and very few with the antagonist. That’s bad, the power balance should be on the antagonist’s side, so I had to reconfigure the groups and their placement. Once that was done, my protagonist’s life got a lot harder and writing conflict got a lot easier.

Timelines

Another visual organizer, linear this time, is a timeline. I’ve just started to use these, experimenting with Aeon Timeline which I like a lot so far, and it gives you a great free trial period which is measured by the number of days you actually use the software. I think it’s for twenty days, which means if you use the software once a week, you’ve got it for twenty weeks. I really like their customer support, too. TikiToki has a free version of its timeline that’s provided as a sample for its paid version.

Keeping It All In One Place

For organizing all of this stuff, I use the journal for the hands-on paper and glue stuff, often printing out the mind maps and diagrams and pasting them in so I can see it all in one place. For online notes, I use VooDoo Pad, my wiki software, a place where I can put everything about my story, including full drafts, in one place with embedded links. You start with a main page/table of contents.

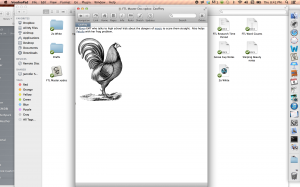

Clicking on any of the titles takes you to a secondary page. “Short Stories” takes me to the list of short stories that are going to make up an episodic fantasy I’m playing around with. Clicking on the title of the first short story takes me to the outline for the story. Clicking on the scene tag in the outline takes me to the rough draft of that scene (that’s a first draft so it’s very bad):

That image is two different Voodoo Pad windows side by side.

Clicking on Characters on the index page leads to a list of characters. Clicking on a character leads to a page with my notes on that character. Click on “Locations” and you go to a page with a list of locations. Click on one and it leads to a page with my notes and pictures for that location. The pages are pretty much endless so you can get a lot of photos on one page.

And of course it’s a great place to store all those computer diagrams and visual notes.

Visual notetaking like this can help you see your book a lot more clearly because you’re breaking out of linearity and words. I don’t use all of these approaches on every book, each story seems to demand something different, but I always use collage because it’s the easiest way for me to see the book as a whole while I’m still drafting, and I always use some kind of mapping at some point so I can see my story’s parts in relationship to each other.

HOWEVER . . . aside from collecting pictures as I go, I do all of the mapping and diagramming after I’ve written most of a first draft. Write first, then organize what you’ve got. Or not.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

March 6, 2014

Arrow Thursday: Back Story. Ack.

I’m coming to the conclusion that this is just not my show any more. Lots of good writing decisions in this episode, including sticking to only two plots that are tightly related, so excellent, focused structure. I love the Russian, hope he comes back more often. I don’t trust the reverend, but that’s just me and he’s a great character. Slade is fantastic, and Slade with his hand on Moira’s shoulder is better than fantastic. Loved watching Oliver’s head explode (because he knows what that hand on Moira’s shoulder means, having put his hand on many shoulders in the past). So what’s my problem?

The actual storytelling has slowed to a crawl because the back story is sucking the life from the main story. If you look at how the story actually moved in this episode it comes down to “Oliver knows Slade is in town and is making a move on Moira.” That’s a great scene right there, but it’s not a story. All of the stuff in the present was fun (except, dear god, they’re turning Felicity into Laurel, the Bitch in Impractical Shoes), loved the stuff in the Queen house except for Sara, who ran the gamut of emotions from A to B (thank you, Dorothy Parker). But the back story . . .

Okay, here’s the problem. With the exception of how the Russian got off the boat, we knew all of that. We knew Slade was gunning for Oliver because of Shado (although trying to sell the idea that Oliver chose Sara over Shado when he didn’t is just ANNOYING), we knew that Oliver was separated from Sara. We’ve talked about As You Know Chat on here; the island story was As You Know Action. I realize that a lot of people like that, which is why I’m not saying the stuff on the island is bad, I’m saying it left me cold, while taking away screen time from the things I love about this show, the Arrow team working together and Moira being the Hot Iron Lady. Oliver, Roy, and Sara boxing in Slade was excellent; give me a whole episode of moving the story forward with the Arrow team like that, and I’m there. Instead I got As You Know and explosions in the dark. No, thank you.

It wouldn’t have been so bad if I hadn’t just watched Person of Interest‘s massive back story episode from this week, “RAM.” The entire episode except for the coda at the end was played in the past, and we knew nothing about any of it, so it was all new information played out in a plot that had a beginning and an end. It was, in short, story.

“Ram” began with a number coming up as usual, but this episode was set in 2010 so it’s pre-Reese. Finch is working with an ex-mercenary who is Finch’s compromise: he needs somebody tough enough to take out the bad guys, but that gives him Dillinger who walks the line between good and evil like a drunk on a bender. There are three different groups–Control, the CIA, and Decima–trying to kill the number this week, including Reese as half of the CIA hit team. As Finch sorts through the groups, Dillinger brings the number back to the library and steals the briefcase, and then the plot becomes a Chinese box, opening up with answer after answer to all the mysteries from three seasons–How did Finch find Reese? Who ordered the hit on Nathan? Why was Reese targeted for death in China?–while moving the story of how the hell Finch is going to save the number by himself (for one thing, he gets out of his wheelchair and limps into the real world again). Instead of back story showing stuff we already know, “RAM” is an origin story, showing how Finch, Reese, and Shaw all entered the same story space, tying off pretty much every mystery the series has been spinning since the beginning, and ending with a coda in the present that has Root bringing the number back into the game for the Machine, telling him, “She needs you.” It was magnificent storytelling, and I couldn’t look away for a moment, every second on that screen was new and moved story, which it gave both an ending–the number was saved–and pushed into the next episode–what the hell is Root doing?

Meanwhile on Arrow, I found out that Slade has the mirakuru, that he wants vengeance on Oliver for Shado’s death, and that the Russian escaped. Oh, wait, I knew all of that. What did I learn? Uh, there’s a character who’s a preacher? And the back story ends in another cliffhanger. Okay, but what about the now of the story. Oliver finds out Slade is town and is hitting on his mother. LOVE it. What else? Uh, that’s it. The big climax is Slade repeating the threat he’s already made several times. So no real story there, either. Sum up the entire episode: Slade is working to make Oliver pay. Wait, we knew that. By possibly making a move on Moira. Okay, that’s fun, but most of us saw that coming. What’s new? Nothing.

I really need story. I need a story that starts in the first scene and gives me closure at the end, I need new stuff happening all the time, I need to be surprised and delighted, and Arrow used to do all of that for me. But now their story pace has slowed to a crawl, there’s nothing new on the screen, and they’re not ending their weekly stories. So I’ll come back for the Suicide Squad (that’s next, right?), but if they do the same meaningless stuff with that that they’re doing here, I’m done. I’ll wait until the end of the season and watch the rest of the episodes together, fast forwarding through the back story and watching for the characters I love: Diggle, Moira, the Russian, Deadshot, Slade, Felicity if they put her character back together (why was she wearing all of her mother’s jewelry?). But weekly viewing? No. I need story.

I will, however, be glued to the screen every week to find out what happens next with the Machine gang, especially this chick:

She could take Slade without batting an eye because she does new things that nobody expects. And then she finishes the job and moves on. Root knows story.

Fiction Archeology 2: Plot and Subplot in You Again

One of the problems of digging up an old, stalled book is that you’ve eliminated so many of your options already. You Again is a murder mystery/romance; the mystery/father hunt/ghost story is the main plot and the romance is the first subplot. The second subplot is Scylla vs her love interest, the secondary romance. But there’s also the third subplot, the plot that Rose is hatching, the bed-and-breakfast plot, which is why she’s lured everybody to the house.

So that’s three subplots. For a novel, that’s not impossible, but it’s not good, either. And of course every character in the book has his or her own reason for coming to Rosemore, Isolde is hoping for a job, Nora thinks Malcolm’s been embezzling, and so on, and they all have secrets they don’t want revealed. So the key is to tie everything to the main plot or a subplot, and then make sure all the subplots echo or interact with the main plot.

So back to the mystery main plot. That’s tied to a trust fund that will be liquidated (is that the right word?) on January 1st. (The story starts the day before Christmas and ends on New Year’s Day.) So the goal of the murderer is money.

The romance subplot intertwines with that because the first murder shifts Zelda’s outlook on life considerably; if it weren’t for the shock of that death, Zelda wouldn’t become open to new things, like sleeping with James-Spenser-Sam (dear god, I have to find a name for him), and the fact that she’s sleeping with him increases the pressure on the murderer. So I’m good there, plus the more the tension rises with the threats from the murderer (they’re snowbound), the more pain there is, and pain spikes adrenalin which fuels passion. I’ll have to look at it again to make sure the main plot needs it, that if I took the romance plot out of the book, the main plot would suffer, but I’m pretty sure it’s inextricably intertwined with the main plot.

Scylla’s romance subplot echoes Zelda’s because the same murder shifts her perspective on life, and when that shifts, so does her view of romance. Her character arc is the reverse of Zelda’s, so that’s a tie to Zelda’s plot, too. Plus she and Zelda are partners all the way, so anything one does, the other is part of, which means that when Zelda starts looking for the killer, so does Scylla. I’m good with her romance as the second subplot. Still, I need to make things she does as part of her romance plot things that are essential to the main plot, so that’s something else to keep in mind. The problem with secondary romances is that they too often feel like secondary plots, something thrown in at the last moment instead of something integral to the plot.

Then there’s Rose’s bed-and-breakfast plot. It’s her motivation for dragging everybody to Rosemore, so that helps unify things since she’ll be working in the background, complicating things for everybody. Her plot puts pressure on Zelda and Scylla because one approves of it and one doesn’t. Her plot pushes the romance because it’s in her best interest to have Zelda and James Etc. together. Her plot pushes the Scylla romance plot because Rose has an investment in Scylla’s choice. It still needs to be tied more tightly to the main plot. Must cogitate on that.

So, Murder Mystery, Romance, Second Romance, Bed and Breakfast. That’s do-able in a novel-length story although I’d be happier if there were only two subplots. The Murder Mystery is definitely the main plot, so it has to start in the first scene, not necessarily with a body, but with a lot of foreshadowing. The Romance has to start there, too, with foreshadowing, building up expectation of the first meet (which in this case is two people who haven’t seen each other in eighteen years). The Second Romance has to start fairly soon, within the first three or four scenes, I think. And the Bed and Breakfast starts in the first scene for sure.

Right now, the beginning of the first act, with the Murder Mystery in bold and the Romance Plot in italics . . .

1. Zelda vs. Scylla: Arguing about the Bed and Breakfast

2. Zelda vs Rose: Negotiating the Father Hunt/Murder Mystery, Bed and Breakfast, Previous murders (Ghost plot?)

3. Scylla vs. Quentin: Bed and Breakfast, the Second Romance Plot

4. James vs. Mike: Arguing about the Bed and Breakfast (echo scene 1)

5. Zelda vs. Quentin: the Father Hunt/Murder Mystery

6. Zelda vs. Rose: The dinner party (there’s conflict here, but it has to change because I’m taking the thing they’re struggling over out of the plot, but I’m keeping the part where she warns Zelda to stay away from James)

7. Scylla vs. Mike: The Second Romance Plot.

8. James vs. Rose: Bed and Breakfast, Romance Plot (she warns him away from Zelda)

9. Zelda vs. James: Bed and Breakfast, Romance Plot?

So the first scene does nothing but set up the minor subplot so I’m going to have to cut that. That makes Zelda vs. Rose the first scene and that does start the Murder Mystery. But then I lose the echo in James’s scene with Mike, which may also be just set-up and need to be cut. Nope, that would put James entering the story in what would then be the sixth scene and that’s too late. Hell. So 1. Zelda vs. Scylla has to include the Father Hunt, which could easily devolve into As You Know Chat, but if I can figure out a way around that, that will make it part of the Murder Mystery. All I have to do is make sure that “1. Zelda vs. Scylla” and “4. James vs. Mike” are not Set-Up Chat, and I can make that work. Although the fourth scene is still pretty late to bring James in. Better make that the third scene. Argh.

Then it’s gets trickier because almost all of the work I’ve done on this has been first act stuff. (Yes, my first act ran very, very long.) I know the first act turning point is the first murder. The second act point of no return turning point is the second murder. The third act crisis . . . I had that a third murder but I think that strains credulity. So now it’s back to the drawing board for the acts plan, and wading through all the first act stuff I’ve already written to see if there’s anything worth keeping. But by god, I have a main plot with two integrated subplots. That’s something. I really have to figure out how that Bed and Breakfast subplot works with the main Murder Mystery, though. And starting that minor B&B subplot in the first scene isn’t good, so no on that. ARGH.

Back to reading old drafts. And while I’m at it, revising the collage again. The early version is up at the top; below is a later version, but neither of them are right for where the story’s going now, so there will be tearing off of images and a lot more scissors-and-glue in my future: