Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 271

April 4, 2014

Questionable: Bodies in Motion After Concrete Goals

Tamsin asked:

How do you get your characters to ACT? (I’ve realised that my perennial problem is that my default is characters that don’t have any goal and don’t want anything (because it’s dangerous to want) – and it is interesting (to me ;-)) that I’m just starting to be able to write characters who have some kind of goal/desire (however limp), just as I’m managing to action that in my own life for the first time too – probably no coincidence! But any tips on how to cattle-prod my characters into further narrative-carrying goals/wants would be really helpful!

You’ve pinpointed your first problem: if characters don’t have goals, they don’t have any reason to act. So get those suckers some concrete goals. That is, they don’t want inner peace, they want the ark of the covenant. If your character’s goal is an abstract like inner peace or happiness, find something concrete that will represent that for him or her, something that she thinks will bring her inner peace or happiness if she achieves it. But it has to be concrete, something that exists as an object in the real world, so that she has to use her physical body to acquire it. It has to be something she has to move through physical space to get. Your character’s goal is so central to the entire story that if she doesn’t have one, you don’t have a story, so I’d go back and look at what made you want to write the story in the first place and see if there’s a concrete goal there that you missed.

The next step is to make sure that goal is life or death to the character. It can be a psychic death, but it has to be so great that he or she will cross boundaries to get it, it has to be essential to her well-being, to her concept of self. If she doesn’t get that goal, she’s not the person she thought she was, her identity will disintegrate, and she’ll die that psychic death (or real death, depending on her antagonist).

After that, you have to reorder the way you think about character on page, and here I sympathize, believe me. If I could, I’d do all my books in dialogue. The problem is, dialogue often lies. That’s because people lie. They don’t just lie on purpose, they also lie to themselves to make a situation less painful, they interpret the truth to mean what they want it to mean, they tell themselves that things are fine when they’re not.

But people’s bodies don’t lie. If I stand up in front of a group and tell them I’m perfectly calm while tapping my fingers on the lectern, they know I’m not perfectly calm. If somebody says, “I’m open to your suggestion,” while keeping her arms crossed over her chest, she’s not open to your suggestion. Talk is cheap, movement is truth.

This is because emotion lives in the body (and thank you, Ron Carlson, one of the best teachers I’ve ever had, for that piece of knowledge). You can write that Susan was shocked, or you can write that Susan saw something, went cold, and threw up. You can write that she was scared, or you can write that the gun slipped in her hand because her palms were sweating. You can write that she was angry, or you can write that she snapped the stem off the champagne glass she was holding. Talk is not character, action is character, bodies betray character, and bodies in motion are the ultimate in characterization.

But the big reason to use bodies in motion is not just character, it’s that movement draws fire, as a friend of mine used to say. It’s movement that creates conflict, people doing things in space and time, not talking about ideas and intentions. The fact that characters want something is meaningless until they begin to move after it; until they take action, go places, struggle with other people, they’re just thinking about the future not taking part in the now. And the fact that they’re taking action means that the antagonist must now take action, move his body through space for a concrete goal, blocking your protagonist, which will force her into more action . . . Lather, rinse, repeat, which I would point out, is a physical action.

So after you figure out what your character wants, the next step is not explaining it to the reader, it’s writing your character’s body in motion going after that goal.

For practice, try writing a scene like a silent movie: no dialogue. If they can’t talk, they’ll have to do something.

The best example I have of this is the brilliant Buffy episode, “Hush.” Joss Whedon had been dismissed as just a guy who wrote great dialogue, so he wrote an entire episode that for the most part had none: Everybody in town became mute and couldn’t even scream. It was amazing and terrifying and you couldn’t look away because you didn’t know what they were going to do next.

Another great place to look at bodies in motion is graphic novels. I love Amanda Conner’s Harley Quinn:

Look how much she does here with no words at all:

Harley could have said a million words about how much seeing that dog hurt bothered her, but instead Connor shows her body reacting, first in tears and then the implosion in her eyes as she loses it, then her body launching toward her antagonist, and finally the physical exhilaration of the freed dog and her happiness. Those two pages would be just fine without any dialog at all.

Character is bodies in motion, so tell as much of your story as you can through movement in pursuit of that life-or-death goal.

April 3, 2014

Money Is the Root of Evil

Questionable: Character Arcs

Tamsin asked:

Character arcs – how do you know if you have a strong one for your character? How do you winkle it out of a character that is refusing to tell you what theirs is?(!) And is there a diagrammatic shape/structure that you use for character arcs? Do characters have separate arcs for different aspects: i.e. an emotional arc and a mystery plot arc or should those be welded together as aspects of each other?

Let’s break this down into its parts first, says the teacher.

An arc in a story is the movement from the beginning (when the conflict starts) to the end (when the conflict ends). Some arcs are higher than others: some things only change a little bit and some things do a 180 degree turn and become the complete opposite. All arcs move from stability to stability; that is, just before the story begins, everything is stable (not necessarily happy, but stable). Then the conflict begins and grows and escalates until everything blows up at the climax, at which point everything settles down into a new stability and the arc ends.

There are two kinds of arcs, plot and character.

An example of a plot arc is a stable story world in which someone is murdered. The story world is thrown into disarray because there’s a killer loose, and as the characters try harder and harder to catch the killer and the killer tries harder and harder to escape detection, the plot arcs in tension, danger, and stakes until finally the detective and the killer meet in the climax, the killer is arrested, and the world of the story returns to stability. This is external plot arc because you’re talking about events between two characters.

An example of character arc is a person who is in a stable situation and who is thrust out of that stability by events (see plot arc) at the beginning of the story and is therefore forced to do things he or she normally wouldn’t in order to survive. While the actions the character takes are part of the plot arc, the impact of the actions changes the character, forces him or her to cross psychological boundaries that were uncrossable before, and with each boundary crossed, the character changes, over and over again, each change greater, until at the end, the character fights the last battle in the plot arc, forever changed emotionally and psychologically from the battle, and achieves psychological stability again, his or her character arc finished. This is internal character arc because you’re talking about emotional/psychological changes within the character.

Events cause character change, and character change is demonstrated in event, which means that plot arc and character arc are inextricably linked. If the events of the plot don’t have enough impact on your character to change him or her, the story will lack impact. If your character arcs but the events in the plot have nothing to do with the change, your character will be unbelievable. So what you need is an event strong enough to push your character past a psychological barrier he or she would never cross, which changes your character since a boundary once crossed is destroyed. That change in your character then means that he or she acts differently in the next section of the story, which moves the plot, the events of which escalate to another event that’s strong enough to push the character past the new boundary, which leads to more character arc, which leads to more dangerous plot events, which lead to . . .

Plot should change character, and character should change plot. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Let’s consider Jane, mostly because I’m growing quite fond of our beheaded-Barbies stalker who shoots pigeons out her bedroom window.

Jane works for a multinational corporation in their trouble-shooting department, which means she hires assassins when the company needs them. Jane is very good at her job because she’s absolutely honest, she keeps her personal life segregated from her work, and she lives to support and protect the corporation. She also has a strong moral code: she may hire assassins, but she’s not one. It’s her job to keep the corporation safe, but she’d never hurt anyone.

Our story opens as Jane, having shot her morning pigeon, arrives at work and is assigned a new project: Hire a new assassin to take out a difficult target. The corporation suggests Alan, and when Alan walks into her office, Jane is smitten: he’s gorgeous, he’s funny, he’s smart, and he smiles at her as if he’s been waiting his whole life just to meet her. At the end of the interview, Jane hires Alan, and he asks her out.

Jane never mixes work and personal life, but she can’t resist, she’s fallen for him, and she crosses that boundary. Super-controlled Jane is now making decisions based on emotions. Her character arc has begun.

At dinner that night, Jane has a marvelous time; Alan is even more amazing than she realized. But as they’re leaving the restaurant, they run into one of Jane’s co-workers, who pulls her aside and says, “Isn’t that the new assassin you hired?” On the spot, knowing word will get back to her superiors and her perfect record will be sullied, Jane lies in her teeth and says no.

Jane never lies but she has to protect her job, so she crosses that boundary. Now she’s mixed her personal and professional lives and lied about it, and since she’s done those things once, she’ll have to keep on doing them, which will bother her less and less. Her character is arcing.

Jane and Alan walk through the park, trading stories about their lives and achieving a perfect understanding, right up until the moment when they’re in darkness under a bridge. Alan pulls Jane to him and kisses her passionately, and then says, “I’m sorry, I really like you,” and pulls out a gun. Jane, acting on instinct, knees him in the groin and takes the gun, and says, “What the hell, Alan?” and he tells her that he was hired to kill her: the corporation is phasing out the assassin department and she knows too much, so her severance package is a bullet. Jane stares at him through a red mist of rage, betrayal, and corporate vengeance, says, “Alan, as far as I’m concerned, you’re just another damn pigeon,” and shoots him between the eyes.

Jane has never killed before, but the events have pushed her across that boundary, and now she sees clearly that her allegiance to the corporation as its head assassin wrangler has been for naught. That finishes Jane’s 180 arc: she’s mixed business and pleasure, she’s lied, she’s killed, she’s lost her belief in the defining institution of her life, and now she’s a brand new Jane. The honest corporate helper monkey is gone and Jane the dangerous ass-kicker has been born.

Jane puts Alan’s body in his trunk, goes to the home of the head of the corporation and tells him she knows where all the bodies are buried (literally), and that he’s going to give her a promotion, and oh, by the way, there’s a body in his front yard he’s going to have to do something about. As the story ends, Jane’s in a new and better apartment, shooting a new and better pigeon, getting ready to go to her new and better office as senior executive vice president in charge of anything she wants, prepared to take out anybody who gets in her way. In particular, she thinks, it might be time to go see Richard about those headless Barbies . . .

So keeping all that in mind, here are the answers to your questions:

How do you know if you have a strong [arc] for your character?

Look at who your character is in the first scene and who he or she is in the last scene. If the character hasn’t changed much, you don’t have much of an arc.

How do you winkle it out of a character that is refusing to tell you what theirs is?

Your character doesn’t know. Look at how much you’ve changed over the years without really noticing it. Instead, look at the events of your plot. What kind of impact does the inciting event/first scene have on her? How does that force her to begin to change? Then go through each event in the story to see how each changes her character incrementally, and how those character changes drive events. (Remember, most character change happens through conflict, so you’re doing the same thing for your antagonist.)

Is there a diagrammatic shape/structure that you use for character arcs?

I use a basic turning-point-and-acts linear plot structure, making sure that the major events at the turning points also swing character into a new direction, but there are any number of ways to structure different kinds of arcs. Whatever works for you is good.

Do characters have separate arcs for different aspects: i.e. an emotional arc and a mystery plot arc or should those be welded together as aspects of each other?

Generally speaking, you’ll have a main plot/external arc and a protagonist/internal arc, and they’ll interlock, as explained above. But you’ll also have external subplot arcs and internal character arcs for other people in the story, so you’ll have a lot of arcs, all interlocking like gears in a machine, and as each one turns, the others turn. Concentrate on protagonist arc and main plot arc in first drafts, and then in later rewrites consider the other arcs.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

April 2, 2014

So Let’s Talk About Endings

It was so nice of the How I Met Your Mother people to schedule their much-reviled series finale the same week I’m teaching endings at McDaniel. I’ve only seen half a dozen episodes of HIMYM, so I have no investment in the finale, but I am interested, as always, in the reactions to story by readers and viewers. And this is a big reaction.

We’ve talked here before about the contract with the reader, the promise the story makes at the beginning. In the case of HIMYM, it was that the story would end with how Ted met his children’s mother. SPOILER: Nine seasons later (and sometime we should talk about stories overstaying their sell-by date), in one episode, Ted meets the woman who will be the mother of his children, marries her, has the kids with her, sits by her bedside while she dies, and then goes to find the woman he’s loved all along, “Aunt Robin.”

Viewer reactions have not been good. Again, I’m not a regular viewer, but just looking at the facts in the above paragraph, I can tell you that if you promise the reader something and then after nine years deliver it and take it away again in forty minutes, you’re kneecapping reader satisfaction in a big way. The speed of the resolution, the neck-snapping turns the plot took in those forty minutes, the abuse of characters established over nine years in under an hour, all led to a feeling that the writers had said, “Fuck it, let’s end this sucker and go get a beer.” This is bad because it violates the number one rule of endings:

You have to make the climax the best part of the book because if it’s not good, the whole story goes under.

Why? Because it’s the promise that’s kept the reader reading, that need to see the protagonist and antagonist face off in a fight to the bitter end, to see the girl get the guy she deserves, to see everybody back in a stable world, the story finished and reader catharsis delivered. Beyond that, it’s bad just because it’s the last thing the reader reads and therefore the thing she’ll remember most. If the climax doesn’t deliver, your story is toast.

What’s most interesting to me about a lot of the internet chatter about HIMYM is that there are people defending the finale because everything in it was foreshadowed in the previous nine seasons, or because it was clear that that’s what was right for the characters, or because that’s what the fans wanted. It’s as if they just explain the ending, everybody will say, “OH, now I see,” and change their minds. But people have already seen the ending and they didn’t like it; the number of people tweeting, “It wasn’t called How I Met Your Aunt Robin” must be in the hundreds by now. If an ending tanks, explaining why it was good is useless. If people didn’t like it, it wasn’t good.

My lecture on endings has this to say about the impact of the story climax:

Bob Mayer and I used to argue about the Most Important Scene in a story. He insisted that the first scene was the most important because it set everything up, introduced the protagonist, and put the story in motion. But mostly, he said, the first scene was the most important because if your reader didn’t like it, she wouldn’t read the rest of the book, making any other scenes in the story moot.

I argued that the last scene was the most important because that’s the pay-o�ff for the reader, the big finish, and if that scene doesn’t satisfy her, everything that went before it was wasted, the entire story experience falling flat, which leaves you with a frustrated, unfulfilled reader. Have you ever read a book that started slow but had a magnificent finish? Did you read that author again? Have you ever read a book that was wonderful right up to the end, but failed miserably at the climax? Did you ever read that author again?

Or as Mickey Spillane put it, the first page sells the reader on this book, and the last page sells the reader on the next book. I’m less interested in the selling aspect and much more interested in the reader satisfaction aspect, but the ideas are the same: fail at the beginning and the reader might stick with you to get to a great ending, fail at the ending and the entire story fails.

I asked the McDaniel students to talk about bad endings they’ve read and great endings they’ve read, and I’ll extend that to film here. What makes a great ending? What endings have failed for you? Reaction to the examples is subjective–I’m one of the few people who think the ending of The Sopranos was brilliant–but I think the reasons behind the reactions are objective: What kills an ending for you? And more important, what makes for a great finish?

April 1, 2014

Organization: This Time It’s Going To Work

I am hellishly unorganized which is why I live and work in chaos. This is dumb, so I’ve been working on changing that, and things are actually starting to improve. The funny thing is, I owe it all to software programs. Forget finding inner peace and achieving awareness, I needed to find the programs where I could put things so that I could find them, and one program that would remind me what I needed to do now that I could find the things.

It all started when I began to look for old WIPs that I knew were stashed all over my hard drive. You Again was the kicker; I had–no exaggeration-thousands of files for that sucker, many of them duplicates or corrupted copies I couldn’t even use.

So I opened a Scrivener file for each of the books I was working on and started in slotting the stuff I had so that all my current drafts were in one place, along with the really important working notes and pictures.

That still left me with mountains of info, so I made wikis for each book in Voodoo Pad (VooDoo Pad is Mac only, sorry.). That forced me to go through everything, cutting and pasting what I wanted to keep and trashing the rest.

Scrivener and Voodoo Pad were great, but they couldn’t keep track of time in a story for me, so I added Aeon Timeline which talks to Scrivener, thank God, and got all my dates in times in one place.

Now my fictional worlds were finally under control. If only my real world could be. Then Lifehacker did an essay on organizing your life (they do those a lot) and mentioned a program called Things just in passing. I clicked on the link, thought it looked promising, downloaded the fourteen-day free trial, found out it was fifty bucks and went back to Evernote.

But there was a problem. Evernote is great if you have complex life full of events and tasks and projects that you want to organize. My life is relatively simple: I live in a cottage and I make stuff up. So what I needed was a program that would let me make to do lists and then tell me when I had to do that stuff. That’s all.

So I went back to Things, a program that’s so simple, it doesn’t have a manual. (It’s also Mac only; sorry.) I had the basics down in under two minutes. You click on the Projects button and give the project a name–You Again, Kitchen, Chores, Car, whatever. Under that you click on the Add button and you get a line in your To List so you can break down the job into small parts: Synopsis, Hang Shelf, Wash Dishes, Call Toyoto, whatever. Then you assign a due date for each To Do. That’s it. It does other things–you can assign tags and add notes, etc.–but it does the one thing I need–generate daily to-do lists–and it does it really well.

The most valuable thing about it so far is that it’s shown me why my life is in chaos. There was so much to do that it wasn’t possible, so I’d get overwhelmed and shut down. My first to do lists weren’t broken down into small enough tasks, so I’d look at my list for a day and realized it would take forty hours to do what I’d scheduled in twelve. Back to revising the lists, stretching out the time periods for getting things done, making the tasks smaller. My second to-do lists were much better, until I realized that scheduling sixteen-hour work days wasn’t a good idea, either. I can do that for one or two, even three days, but week after week? No. So I went back in and reassigned due dates again, which is easy to do in the program.

It’s going to take me awhile to get the hang of all of this. But even though I’m still in the learning curve, I can now find all my current drafts immediately side by side with my working notes in Scrivener; Voodoo Pad and Aeon Timeline are finally getting my story worlds in sync; and Things is teaching me that not getting things done doesn’t mean I’m lazy, it means I scheduled too much again and to reward myself because the list of things I have checked off is amazing.

If you’re interested in doing any of this, you can find free wiki, timeline, and organizational software pretty easily, so buying all of these programs is by no means necessary. But getting organized? Yeah, that’s necessary, and if I can do it, anybody can do it.

So tell me, Argh People, how do you organize your life?

March 31, 2014

Questionable: Back Story and Flashback

Katie Redhead said:

I vote yes to discussing how and when to deploy backstory effectively . . . And maybe I’m sort of asking another question all together about flashbacks vs backstory and whether which way we get the information makes a difference to how I feel about a character.

Let’s start with what back story is, then go on to the difference between flashback and memory as a way of putting back story on the page, and then talk about back story and character.

Back story is the stuff that happens before the story starts.

If you are writing in classic linear structure, your story begins when the conflict starts and ends when the conflict ends.

That stretch of time between the beginning and the ending is the now of the story, the events unfolding in front of the reader, the events that make the reader part of the story.

Anything that happens before or after the now of the story is not story because it’s stuff that happens out of the time of the story. The common term for events previous to the story is “back story” but it should more accurately be called “history,” because it’s not part of the story it precedes and so is not story at all in that context.

Because your story is happening now in the reader’s mind, it’s a living thing; every time you interrupt the story to explain back story, you cut into it and make it bleed. Therefore, back story should be avoided at all costs.

Note: This applies only to linear/chronological storytelling. If you’re using a patterned narrative, you can go all over the place.

Flashback and memory are the two most common ways of screwing up your story in the now with back story.

A flashback is an event from the past shown as a full scene as if it is happening now, even though it isn’t. (The flashback, like the cake, is a lie.) Flashback cuts into your story to take the reader back to an event in the past so that she can read a scene that is not only not part of your story, it has no relevance to your story because what actually happened in the past is gone. The facts of the event evaporated right after it happened and it immediately became memory, or rather memories, the different versions that the people who were at the event constructed to explain it. There is no past in the now, there are just memories of what people think happened in the past, so what actually happened at that event is irrelevant and unknowable. So flashback in a chronological narrative is essentially useless.

Memory happens when a character in the now of the story remembers something that took place in the past. It’s better than flashback because it’s part of the now of the story, but it’s still deadly when misused because it results in sittin’ and thinkin’ scenes in which nothing happens, so the plot doesn’t move and character doesn’t change.

Basically, back story kills.

But, you ask, what happens when the stuff that happened in the past is important and must be on the page?

Look at your definition of “important.” If it really means, “It’s easier to explain this character by showing an event in her past,” that’s not important, that’s a misconception on two points.

The first is that a character’s reaction to any past event is an explanation for current behavior. Ten people can be traumatized by the same event, and they will react in ten different ways, take ten different paths, because no human being reacts to events in exactly the same way. So dropping the back-story-as-fact (which is really a subjective memory) into a story to explain something is useless.

The second is that one event in your character’s past does not inform her character, it’s the thousands of events that have happened to her since birth that have made her the person she is today, along with whatever genetic dispositions Nature packed into her before birth. That one event may be a piece of the puzzle the character is now, but it in no way completely explains or motivates her behavior now

Therefore do not use back story as explanation or motivation for character action: character is what we are now, how we act, what we say, how we think now, not what happened to us in the past. I can’t make this strong enough: Dropping big chunks of back story into the now of the story to explain something is useless and damaging and should be avoided at all costs.

Yes, I know that’s upsetting. Now let’s look at how you can use brief memories of back story in the now of the story to build and arc character.

Let’s start with our character, Jane. Jane is at a party chatting away, when Richard walks into the room. Jane freezes. The person Jane is talking to says, “What’s wrong, Jane?” Jane says, “There’s that bastard, Richard, who ripped off the head of my Barbies when I was six.” The person Jane is talking to says, “Let it go, Jane, you’re forty-two, it’s time to move on.”

If Jane does move on, you can cut that entire bit because that piece of back story, while fun, is completely unnecessary to the story.

If Jane does not move on, if the thought of her topless Barbies now haunts her and she begins to stalk Richard, planting Barbie heads everywhere he goes and slowly driving him mad, you can keep that bit and leave the back story as that one line. The reader knows all she needs to know to understand that Jane is a complete whack job, not because of what happened in the past but because of Jane’s actions now. Character is action now, not in the back story. What makes the Barbie back story important is not that it happened, but how Jane is acting on that memory now.

Have I mentioned that you should stay in the now of the story?

The key is to only give as much back story as the reader needs to understand the story she’s interested in now. She doesn’t want a flashback to Richard topping Barbies because she knows that happened. Move on, she thinks, What’s Jane doing to Richard now? Ah, he’s just found a Barbie head floating in his French onion soup, its plastic tresses tangled in the cheese. Now Richard’s throwing up on the waiter. Who cares what he was like when he was six, what’s he going to do now?

The key to back story in the now of the story is, why is this character remembering this now? What has happened in the now of the story to bring this memory back now? Why is this memory important now? What is that memory going to spur the character to do now? The memory isn’t what’s important, what really happened in the past isn’t what’s important, what’s important is what’s happening now that’s going to make the character do something now to change the story now which will in turn change her character now.

In short, stay in the now.

And now, looking into my crystal ball, I foresee these questions:

Can I have my character think about back story if something in the now of the story triggers the thought?

Okay, remember you’re in the now of the story. Richard has just said something to Jane that made her remember that he ripped the head off her Barbies. How much time does Jane have to think before she snaps at Richard? Whatever you write has to be in real time, Jane can’t remember the whole sordid story in the middle of the conversation because (a) people don’t have long memories when they’re involved in conversations, especially if they have a violent reaction to the memory, and (b) Richard’s gonna notice that long silence and ask questions about it. So you get exactly as much time to write back story as Jane has to think the thought and continue the conversation. Which probably means something like You bastard, not a detailed image of how the Barbies looked topless.

Fine, she’s not in conversation, she’s staring out a window thinking about the whole thing. Is that okay?

A scene is two people in conflict. If she’s staring out the window thinking, she’s passive, alone, and not in conflict and therefore not in scene and therefore you’re not telling story. You can fix it by putting somebody else in the scene and creating conflict, but then you’re back to conversation (see Jane and Richard above).

Okay, FINE. How the hell do I do back story then?

You don’t. If it’s not part of the ongoing plot, people don’t need to know it. Write the story without the back story and give it to your beta readers; if they don’t ask for more information, the story doesn’t need it. If they do, find a way to make the information BRIEFLY part of the ongoing plot, usually by somebody in the now questioning the actions of a character in the now and demanding an explanation.

Yeah, I know that’s hard. I’m working on two different novels right now that are lousy with back story, so I feel your pain.

In conclusion:

Most of the time you don’t need back story because what’s happening now is what’s important. When you do find you need it, it’s because something happening in the now is caused by the back story resurfacing in some way and that reemergence becomes part of the now. It’s not what happened back then that’s important, it’s the effect of that event on the current story that’s important.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.

March 30, 2014

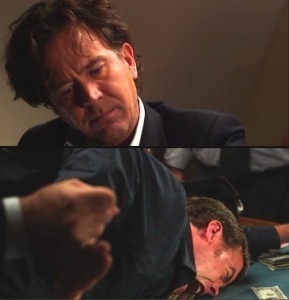

Leverage Sunday: The Bottle Job: External/Internal Character Arc

“The Bottle Job” is one of the last episodes in Season Two, the season of Nate Ford’s descent into darkness, and it’s the clearest indication that Nate is close to hitting bottom because it’s the clearest illustration that Nate’s internal conflict is hurting the way he directs the team’s external conflicts and, by extension, hurting the team.

External conflict takes place between two characters struggling to achieve their goals, so Nate’s external conflicts are always easy to see: He’s going to take down some greedy guy in a suit who’s victimizing innocent people. It’s good clear-cut conflict, no gray areas. Nate’s internal struggle is also pretty clear: He wants to see himself as in control, the mastermind, cool and focused, but when he comes up against the white collar crooks who remind him of Ian Blackpoole, the man who let his son die, all the rage and guilt he’s buried surges to the surface and overwhelms his illusion of rationality. Until he faces the fact that he’s out of control internally, he’s not going to be able to make the changes that will finally give him peace and a clear mind, the things he needs to protect his team and, not incidentally, to sober up. Because he can’t let go of his past, he’s jeopardizing his future and the future of the community he leads.

As “The Bottle Job” opens, the bar that’s become a second home to the team (their first home is upstairs in Nate’s apartment) is having a wake: its long-time owner has died, and his daughter, Cora, a red-head with a sweet face and a broken heart, is rousted by Evil Mark Doyle and his two Evil Henchmen, Liam and Liam’s brother. Cora’s father went to Doyle, a loan shark, to pay for her mother’s medical bills and put the bar up as collateral, now Doyle tells her she has two hours to pay him the $15,000 plus interest she owes him or the bar is his. Unfortunately for Doyle, Nate thinks of Cora as his niece, and Nate does not react well when the children in his family are threatened. He calls in the troops, they set up and run a wire con in an hour, and Nate wins the bar back. Yay, the day is saved!

Except that Nate’s running on internal conflict now, his guilt and rage at Ian Blackpoole transferred to Doyle, and he decides they’re going to take everything Doyle has, humiliate him, and destroy him. It’s an insane decision–Doyle’s dangerous and so are the thugs guarding the safe Nate sends Eliot and Parker to break into, they have no time because Doyle’s about to fly home to Ireland to tell his terrifying father that Boston is theirs for the taking, and most of all, they’ve already saved the client–but Nate can’t let it rest. He denies that it’s reckless, his common sense defeated by his thirst for vengeance.

All of this is made much worse because, in order to make the wire con work, Nate had to drink with Doyle. Where in the first season he drank to dull the pain and rage, his sobriety this season has found him joining forces with this emotions, channeling them into torturing the marks beyond the call of duty. Nobody cares because the marks all deserve it, but now that Nate’s drinking again, it’s the worst of both worlds: he’s unleashed the anger and he’s drinking away his inhibitions, something made clear when he breaks Doyle’s finger after he’s been defeated. The finger-breaking isn’t part of the external conflict, that’s over; it’s evidence of the internal conflict, the honest man Nate thinks he is defeated by the raging sadist he’s become.

What does all of that have to do with community? It’s destroying it. In an earlier episode, Hardison says to Sophie, “We count on Nate to make the plan work, we count on you to take care of us.” But Nate’s plans are increasingly dangerous and ugly, and Sophie been driven away by Nate’s refusal to face his problems; she can’t face hers if she’s trying to keep him in check. So the other three team members draw closer together and watch Nate carefully: they’re still a family, but Dad’s a mean drunk and Mom’s on speed-dial, not there with them, so they have to watch each other’s backs. The place that’s supposed to their haven–their family–has become the most dangerous place to be.

This is an incredibly risky thing to do on a show that’s built on community. It’s brilliant character work, showing a man disintegrating from his internal conflict played out in external conflict, but it undermines the thing that brings the audience to the show: They want to see a great team in action–competence porn–that is also an emotionally bonded family. When the bonds of the community break, the bonds of the audience to that community weaken, too.

This has happened on two different shows aired this year. The first, Person of Interest, killed off a major character, the heart of the Machine Gang, and the team disintegrated because of it, one of the most important members quitting because he couldn’t save her. Losing and then bringing that team member back became the focus of several episodes as the PoI writers took a potentially damaging story line and used it to strengthen the community by showing the community dealing with its grief and then rebuilding itself. (The scene where Reese tells Finch he’s going to need a new suit and Finch realizes he’s coming back is one of my favorite scenes of the entire series; the look on Michael Emerson’s face is so poignant that you know exactly how much Reese and the Machine Gang mean to him.)

The other show is Arrow, a story with multiple subplots anchored by a central team of three. The Leverage producers have talked about their assumption that people tuned in for the cons, only to find out that scenes that viewers liked best were the five team members together in a room, interacting. I think Arrow was much the same: as long as all those insane, soapy subplots were anchored by three sane people in an underground lair figuring out how to stop crime, the show worked. When the writers moved away from the central three, playing the majority of plot points with people outside the team and drawing the protagonist away from his two partners, the show lost its center, and for some viewers, that’s resulted in a loss of faith in the authority in the text; that is, they don’t think the writers see what’s happening as a problem within the world of the story.

I think the key to any move that hurts a central team is in making it clear that the damage to the team is the result of internal conflict–the protagonist who lets his demons overwhelm his rationality and weaken the team–and that the story knows that’s a bad thing. The Leverage writers demonstrated over and over again that Nate’s detachment from the team was trouble, that he was going to hit bottom, and that the team was suffering from it. The Person of Interest writers showed Reese unraveling from his crisis of conscience over more than one episode, and then showed how the Machine and Finch brought him back. In both cases, viewers were uncomfortable but they stuck because it was clear that the writers understood that the disintegration of the team was a disaster, and they trusted the writers to fix it. The problem with Arrow is that it’s fairly clear that no one within the story thinks Oliver’s detachment from the central three is a bad thing, no indication that Oliver will pay for distancing himself from the team. In fact, Oliver’s hypocrisy and occasional outright stupidity is rewarded within the story. Two of the shows used the protagonist’s internal conflict to break down and then rebuild a stronger community through adversity, one presents its problematical protagonist and its community breakdown as story-as-usual and therefore not adversity.

I think it’s easy to look at external conflict and internal conflict as aspects of character alone, much harder to look at those conflicts as interlocked with everything else in the story. A story based only on internal conflict is boring and self-indulgent; a story based only on external conflict is shallow and insipid. A story whose external conflict is powered at least in part by its characters’ internal struggles not only adds depth and layers, it gives writers more leeway to do dangerous things in the story before pulling the narrative back from the edge.

Which is why next week we’re watching “The Three Strikes Job” and “The Maltese Falcon Job”: To watch Nate Ford hit bottom, resolve that internal conflict, and save the team he’s almost destroyed.

March 29, 2014

Cherry Saturday: Mar. 29, 2014

Today is Smoke and Mirrors Day. (Nothing up my sleeve and ignore that man behind the curtain.)

March 27, 2014

Subsequently on Leverage, Season Two

Season Two of Leverage is interesting. Having established the team in Season One, the writers test the community in Two: Nate’s sober and mean, Sophie leaves two-thirds of the way through to find herself, and then Nate starts drinking again and comes undone, leaving the kids to band together to survive. Sophie’s departure was not a production decision: Gina Bellman was gone for six episodes on pregnancy leave, so they did the smartest thing possible and kept her in touch with team through phone calls and Skype, but her loss is felt keenly. It’s an oddly disjointed season, which made analyzing it for community growth a challenge.

Still, I think that testing is important for the growth of any community, just as it is in any relationship. “The Bottle Job” is the episode in which Nate starts drinking again, which means it’s a good one to look at for a community that’s breaking from within, so I’m switching to that for Sunday. I’m also dropping and adding shows to the schedule to give better topics on aspects of community. Apologies for the changes.

The New Schedule:

Mar 30 “The Bottle Job” by Christine Boylan (2-14) External/Internal Conflict

Apr 6 “The Three Strikes Job” and “The Maltese Falcon Job” by John Rogers (2-14/15)

Apr 13 “The Inside Job” by Geoffrey Thorne (3-3) Integrating Single Character Back Story

Apr 20 “The Rashomen Job” by John Rogers (3-11) POV

Apr 27 “The Lonely Hearts Job” Kerry Glover (4-15) Integrating Romance

May 4 “The Radio Job/The Last Dam Job” Chris Downey & Paul Guyot; John Rogers(4-17/18) Beginnings, Endings, and Call Backs

May 11 “The Broken Wing Job” by M. Scott Veach & Rebecca Kirsch (5-8) Completed Character Arc

May 18 “The Rundown Job” by Chris Downey & Josh Schaer (5-9) and “The Frame Up Job” by Geoffrey Thorne & Jeremy Bernstein (5-10) Foreshadowing

May 25 “The Long Good-bye Job” Chris Downey & John Rogers (5-15) Endings

March 26, 2014

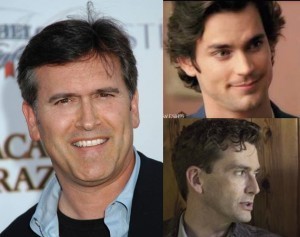

Collaging Character

We’re talking about collage this week in the McD class, and one of the hardest things to get across is that collage is not illustration. While it’s perfectly fine to google for specific things in your story, what you’re really looking for is the look and feel of the narrative, and nowhere is that more important than in the characters.

It’s tempting to just pick one face to represent your character and leave it at that, but I’ve found that it’s too limiting, especially if you’re using an actor in a particular role. At that point, you’re really just using somebody else’s character, so I’ve found it’s easier to visualize my people if I choose multiple faces to represent them. For example, here’s Tennyson from “Cold Hearts:”

Tenn is that color-outside-the-lines guy who spins you a con but who can be deadly serious when necessary. He doesn’t look like any of these guys, he looks like all of them because Tenn is a character, not a face.

Courtney was harder because she’d already been in a story, so I’d already slotted in a picture of her as a supporting character (I’d only used one because she was mostly a voice on the phone). The picture below is from the making of the “Hot Toy” collage showing the original pictures of Courtney and Trudy (angry-looking models from the Anthropologie catalog) along with the altered image that I used for the final Trudy:

So based on what I’d written in the story, Courtney had to have curly red hair and a lot of hostility. Here’s Courtney two years after “Hot Toy”:

There’s probably a twenty-year age span in those three actresses, but it doesn’t matter, none of those pictures is a portrait of Courtney. But taken together they’re an emotional portrait of her; this is who she is on the page (I hope).

This all goes along with the idea that it doesn’t matter what your character looks like as long as you get the character of the character on the page. Readers like to see the story through their own eyes, imagine the characters looking the way they want them to look. Unless a character detail is really important to the plot–something specific about the description has an impact on how the narrative unfolds–what people look like in detail is irrelevant to your story.

Which means it’s irrelevant to your collage, too.