Questionable: Bodies in Motion After Concrete Goals

Tamsin asked:

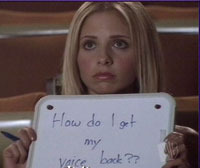

How do you get your characters to ACT? (I’ve realised that my perennial problem is that my default is characters that don’t have any goal and don’t want anything (because it’s dangerous to want) – and it is interesting (to me ;-)) that I’m just starting to be able to write characters who have some kind of goal/desire (however limp), just as I’m managing to action that in my own life for the first time too – probably no coincidence! But any tips on how to cattle-prod my characters into further narrative-carrying goals/wants would be really helpful!

You’ve pinpointed your first problem: if characters don’t have goals, they don’t have any reason to act. So get those suckers some concrete goals. That is, they don’t want inner peace, they want the ark of the covenant. If your character’s goal is an abstract like inner peace or happiness, find something concrete that will represent that for him or her, something that she thinks will bring her inner peace or happiness if she achieves it. But it has to be concrete, something that exists as an object in the real world, so that she has to use her physical body to acquire it. It has to be something she has to move through physical space to get. Your character’s goal is so central to the entire story that if she doesn’t have one, you don’t have a story, so I’d go back and look at what made you want to write the story in the first place and see if there’s a concrete goal there that you missed.

The next step is to make sure that goal is life or death to the character. It can be a psychic death, but it has to be so great that he or she will cross boundaries to get it, it has to be essential to her well-being, to her concept of self. If she doesn’t get that goal, she’s not the person she thought she was, her identity will disintegrate, and she’ll die that psychic death (or real death, depending on her antagonist).

After that, you have to reorder the way you think about character on page, and here I sympathize, believe me. If I could, I’d do all my books in dialogue. The problem is, dialogue often lies. That’s because people lie. They don’t just lie on purpose, they also lie to themselves to make a situation less painful, they interpret the truth to mean what they want it to mean, they tell themselves that things are fine when they’re not.

But people’s bodies don’t lie. If I stand up in front of a group and tell them I’m perfectly calm while tapping my fingers on the lectern, they know I’m not perfectly calm. If somebody says, “I’m open to your suggestion,” while keeping her arms crossed over her chest, she’s not open to your suggestion. Talk is cheap, movement is truth.

This is because emotion lives in the body (and thank you, Ron Carlson, one of the best teachers I’ve ever had, for that piece of knowledge). You can write that Susan was shocked, or you can write that Susan saw something, went cold, and threw up. You can write that she was scared, or you can write that the gun slipped in her hand because her palms were sweating. You can write that she was angry, or you can write that she snapped the stem off the champagne glass she was holding. Talk is not character, action is character, bodies betray character, and bodies in motion are the ultimate in characterization.

But the big reason to use bodies in motion is not just character, it’s that movement draws fire, as a friend of mine used to say. It’s movement that creates conflict, people doing things in space and time, not talking about ideas and intentions. The fact that characters want something is meaningless until they begin to move after it; until they take action, go places, struggle with other people, they’re just thinking about the future not taking part in the now. And the fact that they’re taking action means that the antagonist must now take action, move his body through space for a concrete goal, blocking your protagonist, which will force her into more action . . . Lather, rinse, repeat, which I would point out, is a physical action.

So after you figure out what your character wants, the next step is not explaining it to the reader, it’s writing your character’s body in motion going after that goal.

For practice, try writing a scene like a silent movie: no dialogue. If they can’t talk, they’ll have to do something.

The best example I have of this is the brilliant Buffy episode, “Hush.” Joss Whedon had been dismissed as just a guy who wrote great dialogue, so he wrote an entire episode that for the most part had none: Everybody in town became mute and couldn’t even scream. It was amazing and terrifying and you couldn’t look away because you didn’t know what they were going to do next.

Another great place to look at bodies in motion is graphic novels. I love Amanda Conner’s Harley Quinn:

Look how much she does here with no words at all:

Harley could have said a million words about how much seeing that dog hurt bothered her, but instead Connor shows her body reacting, first in tears and then the implosion in her eyes as she loses it, then her body launching toward her antagonist, and finally the physical exhilaration of the freed dog and her happiness. Those two pages would be just fine without any dialog at all.

Character is bodies in motion, so tell as much of your story as you can through movement in pursuit of that life-or-death goal.