Questionable: Pictures and Writing

Deb Blake asked:

I know you’ve talked a lot about your creative process with storyboarding (is that a word?) and collages and such. I don’t tend to use such things, but I’m starting to make Word docs for each novel that include pictures of my protagonists, and other notable stuff (their dogs, cars, motorcycles). Can you talk a little bit about how you create and organize your pictorial “notes”?

I just went back to the draft to this post to reread my answer and realized that I didn’t answer the question Deb asked, I answered the question I thought she asked. So first, here’s the answer to her real question:

I create most of my visual notes by grabbing them off the net, taking pictures with my phone, drawing diagrams by hand or using Curio, and by creating computer collages using Curio, Elements, or Acorn.

I organize my research images, four ways.

I sort them into folders in the book folder on Dropbox.

I combine them into group images in Curio and Acorn.

I put them into VooDoo Pad docs

And I use book boards on Pinterest.

What I thought Deb asked was how I used visuals. I have no idea why I thought that, her question is perfectly clear. But since I answered it . . .

I think the most important thing about using visuals in writing is that it’s a much more natural way to think. Those lines of type are not the way we navigate through the world. We don’t experience things in straight lines and words, we see this and then that over there and then that other thing over there and we see relationships between them and make connections and assumptions that we don’t always verbalize. We observe life, we don’t read it (which is one of the reasons that comic books and film are such great delivery systems for story), and we often use those observations to make patterns and then use those patterns to determine what’s going on, what things mean. So when we’re trying to recreate real life, it makes sense to try to observe the fantasy we’re creating so we can see those connections and patterns.

There are limitless ways to use visuals, but the ones I use most often are:

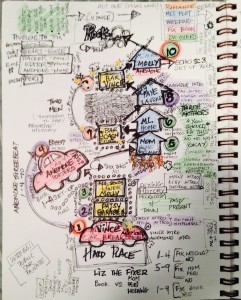

Story Journals:

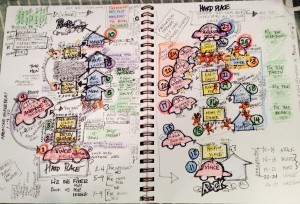

I do a lot of my note taking these days in visual journals. If I want to see all the scenes in an act, I put them on a page in diagrams, starting at the bottom because I want my scenes to rise in tension and because reversing the way I normally see things helps me see everything more clearly. For example, in trying to figure out the patterns in the first part of Lavender’s Blue, I wrote the protagonists for the scenes, starting at the bottom up, trying to place the main plot in the center and subplots off to the side. What I found as I doodled, though, was that I was actually dividing the scenes into spheres. That is, Liz meets some people in public places (yellow squares with lights around them), some in private spaces (blue houses), and some in the mediating space of her car which is both public and private (red cars). At that point I could see patterns in the first act–three mothers in the blue house scenes, the Cash/Vince foil scenes in the bar–and I could see where I was missing things, like Anemone who in this chunk of story only had one scene even though she was a big motivating force. If I wanted her pushing Liz through the plot, I needed more Anemone, so I added some more red in places.

The second act on the right hand page changed when I compared it to the left: I noticed I had another three mothers group, and I realized that the “Fix it, No” thread in Act One had turned into “Fix It, Yes” in Act Two. And I had completely missed the fact that I had three scenes in Vince’s car toward the end, building to the love scene, so I could rewrite those as an escalating series. The diagrams made it easier to divide both acts into scene sequences, too (see notes in lower right hand corners of pages). I could also go back in and doodle the motifs next to the scenes where they were mentioned (pearls, teddybears, T-shirts, etc.) That way I could see if I was repeating them, escalating their importance so I could pay them off in the last act. It’s about here that I start gluing stuff in, which makes the pages a real mess, but that’s okay, this isn’t art, it’s note taking.

And sometimes just screwing around on the page helps solidify ideas. Because neatness doesn’t count on this stuff and because I knew the act was going to end in Liz getting hit with a rock, when I started the first act notes, I doodled “Rock” at the top of the page (the top because I wanted my scene notes to rise in action from the bottom of the page). Then because it’s just doodling, I wrote “Hard Place” at the bottom (ha, amusing myself) and put the car/first scene there, and then realized that was a scene which was a hard place for Liz to be, thanks to her mom and her aunt. When I did Act Two, “Rock” had to go at the bottom, so I wrote “Hard Place” at the top and damn if that last scene isn’t Liz back in her car in a really hard place thanks to her mom and her aunt. Again, that’s something I wouldn’t have noticed if I hadn’t been doodling cars and making dumb visual jokes about Liz being caught between a rock and a hard place

The examples above are in a smooth Bristol journal which will take a lot of abuse–Sharpie doesn’t bleed through this stuff–but you can do this on anything. The key, as in anything visual for writing, is that it’s not artwork, it’s notes. You don’t critique your penmanship when you make notes, so don’t critique your drawing ability or your neatness when you draw notes. (That big grey splotch in the middle is a mistake, not a symbol.)

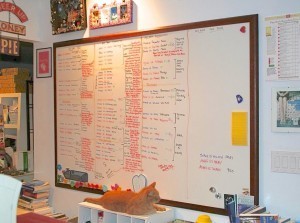

White Boards

Another way to do note diagramming is to do it on a big white board. If you don’t have the wall space, Home Depot has 2′x4′ sheets of whiteboard that are very portable and the perfect size for diagramming an act, a short story, or a novella (okay, you might need two for a novella).

The one below isn’t mine, it’s from the original brainstorming for the movie The World’s End via io9:

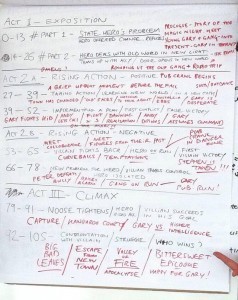

Or do the scene diagrams in a graphics program. This one was done in Curio:

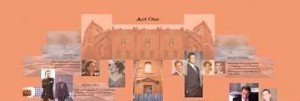

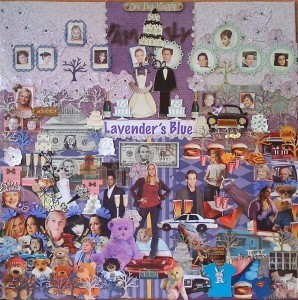

Collage

Collage is probably my favorite visual crutch, a place to combine images that evoke the book into a single image that captures the book as a whole. I’ve written about collage a lot before, so here’s the Lavender collage in progress and a link to the blog post that talks about collaging a series and the Three Goddess Chat on collaging. See also Picture This: Brainstorming as Prewriting and Inspiration and the website page with the discussion of my collages.

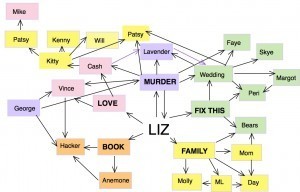

Mind Mapping

Mind mapping is another way to see character relationships, plot and subplot movement, use of motifs, etc. I use Curio software because I’ve had it for years and I like it, but there are any number of programs out there. Even better sometimes is good old pen and paper although it doesn’t give you the luxury of moving things around the way mind mapping software can. I usually end up pasting the finished maps in my journal anyway, just so I can flip to them when I need them.

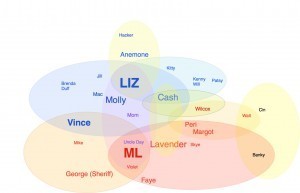

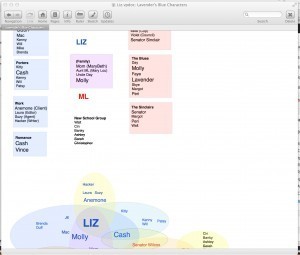

A cousin to the mind map is the character relationship map, a kind of Venn diagram gone mad. Make a list of all your characters and then make a list of the groups they belong to: family, friends, work, school, whatever. Some of your character will be in more that one group and that’s fine. Then write your protagonist’s name large in the middle of blank page with the antagonist’s name large beneath that (leave some space) and the put the groups around the two names, overlapping when names are shared. It takes some jiggering, but when it’s done you can easily see the push and pull of group identities on the different characters. When I did the first one for Lavender’s Blue, I realized that I had aligned everyone with the protagonist and very few with the antagonist. That’s bad, the power balance should be on the antagonist’s side, so I had to reconfigure the groups and their placement. Once that was done, my protagonist’s life got a lot harder and writing conflict got a lot easier.

Timelines

Another visual organizer, linear this time, is a timeline. I’ve just started to use these, experimenting with Aeon Timeline which I like a lot so far, and it gives you a great free trial period which is measured by the number of days you actually use the software. I think it’s for twenty days, which means if you use the software once a week, you’ve got it for twenty weeks. I really like their customer support, too. TikiToki has a free version of its timeline that’s provided as a sample for its paid version.

Keeping It All In One Place

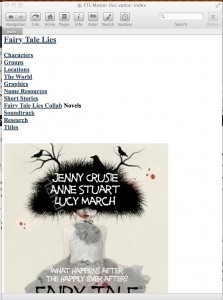

For organizing all of this stuff, I use the journal for the hands-on paper and glue stuff, often printing out the mind maps and diagrams and pasting them in so I can see it all in one place. For online notes, I use VooDoo Pad, my wiki software, a place where I can put everything about my story, including full drafts, in one place with embedded links. You start with a main page/table of contents.

Clicking on any of the titles takes you to a secondary page. “Short Stories” takes me to the list of short stories that are going to make up an episodic fantasy I’m playing around with. Clicking on the title of the first short story takes me to the outline for the story. Clicking on the scene tag in the outline takes me to the rough draft of that scene (that’s a first draft so it’s very bad):

That image is two different Voodoo Pad windows side by side.

Clicking on Characters on the index page leads to a list of characters. Clicking on a character leads to a page with my notes on that character. Click on “Locations” and you go to a page with a list of locations. Click on one and it leads to a page with my notes and pictures for that location. The pages are pretty much endless so you can get a lot of photos on one page.

And of course it’s a great place to store all those computer diagrams and visual notes.

Visual notetaking like this can help you see your book a lot more clearly because you’re breaking out of linearity and words. I don’t use all of these approaches on every book, each story seems to demand something different, but I always use collage because it’s the easiest way for me to see the book as a whole while I’m still drafting, and I always use some kind of mapping at some point so I can see my story’s parts in relationship to each other.

HOWEVER . . . aside from collecting pictures as I go, I do all of the mapping and diagramming after I’ve written most of a first draft. Write first, then organize what you’ve got. Or not.

Standard Disclaimer: There are many roads to Oz. While this is my opinion on this writing topic, it is by no means a rule, a requirement, or The Only Way To Do This. Your story is your story, and you can write it any way you please.