Where Everybody Knows Your Name: Community in Storytelling

Lately, I am fascinated by community in stories. I’ve always known it was important, but a couple of weeks ago I realized that one of the novels I’m working on has a community as its protagonist; that is, it’s a group of stories that taken together, show how this community was formed. The individual stories have individual protagonists, but the book is about this group of people who through the struggles in their various plots are thrown together and bond. And that means I need to know a lot more about how to build and use communities (teams, families, whatever) in fiction. So fair warning: I’m going to be doing a lot of posts about community. I can do that, it’s my blog. (Hey, it’s a step up from dog pictures which I have moved to Refab, so count your blessings.)

Community is one of the most powerful storytelling hooks. The more we trade the sense of real, physical attachment to a group for the virtual community of the internet (Hi, Argh People), the more we need to experience connection vicariously in our stories. The pleasure of reading about a lone protagonist finding a community that supports her and loves her, and the fun of seeing interesting characters come together to become a team are both a kind of love story: people who were strangers commit to each other in a unit that makes them stronger and safer and happier. The successful community story is like the successful love story: the people in it are better together.

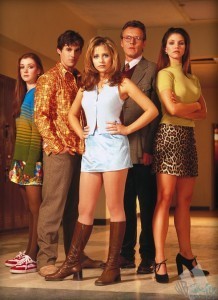

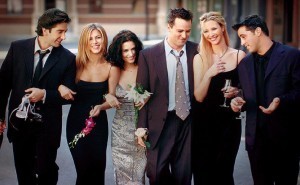

Think of classic TV shows like Friends (“I’ll be there for you”) and Cheers (“You need to go where everybody knows your name”). Buffy was nothing without the Scoobies, Finch in Person of Interest is helpless without the Machine Gang, Oliver on Arrow wasn’t all that interesting until first Diggle and then Felicity made Team Arrow (“Stop”). Frank and Sarah were fun in Red, but the story really took off when they picked up Marvin and the Pig, and then Joe, and then Victoria, and then Ivan, each addition making the team stronger and smarter. Half the fun of community in fiction is seeing how that community assembles, working out their differences and growing stronger with each addition. The reader’s pay-off in those stories is the vicarious sense of belonging, that secret knowledge that if we walked into the bar in Cheers, everybody would know our names; that if we went to Central Perk, they’d make room for us on the couch, that if we stopped by The Pie Hole, Olive would remember our favorite slice. Because we take the journey with the characters, we’re part of their team.

The big problem with writing community is that Community = A Lot of People. If you’re writing a romance, you need to put two love interests vividly on the page and then show them interacting, struggling with each other, negotiating the terms of the partnership, while avoiding long scenes where the two talk about the relationship in favor of short scenes where the two do things that change, grow, and intensify the relationship. Think that’s difficult? Now change “two” to “five.”

So here’s what I think I know about writing community so far:

1. Start with the central figure of the group, the leader/mastermind/source of power.

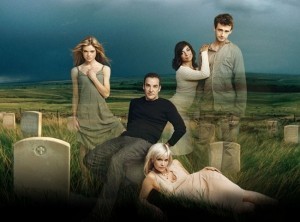

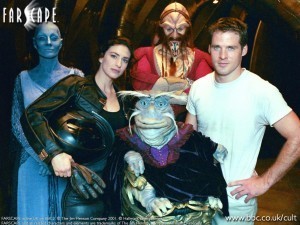

If you look at the pictures in this post, most have a first-among-equals, a leader who anchors the team (Friends is the exception). That character is important because the personality of the character who leads the group is going to characterize the group, which means you get him or her on the page first. She or he is, as a writing prof of mine once said, the stout stake that everyone and everything in the story is tied to. Without Buffy, the Scoobie Gang would be aimless. Without Finch, the Machine Gang would have no focused moral purpose. Without Frank, the Red Gang would just shoot everybody. When you introduce your protagonist/leader first, you introduce the community that’s to come. That means that not only must your protagonist be all the things a regular protagonist is–fascinating, driven by a goal, pro-active–he or she must have a purpose that is difficult enough to require a focused team to achieve. Any protagonist can get a little help from friends; the team leader protagonist has a goal that’s so difficult and complex that he or she needs people who will form one unit to achieve a single goal, his goal.

That means the character of the leader is uber-powerful in shaping the text. For some stories, his character is uber-powerful in the story, too–the fact that Frank has no flaws doesn’t hurt Red although his weakness (Sarah) complicates things nicely and puts a jet pack on his motivations–but if you’re interested in the dynamics of the group, giving the leader a weakness that the rest of the group acknowledges and adapts to can balance the power structure in the group. Sam, the leader of the Cheers barflies, is handsome, famous, and successful. He’s also dumb as a rock, which means that Carla, Diane, and Norm have a level playing field in their negotiations with him (and everybody takes care of Cliff and Coach). A flawed leader means that the group dynamics are less predictable, more dynamic, and a lot more fun.

2. Once you have your leader, build your team around him or her by first putting the group on the page as individuals. That is, you need your group members to be distinctly different from each other so that it’s easy to tell who’s who. If they all look, sound, and work alike, your reader is going to be pulled out of the story trying to identify who’s doing what.

The group above is three dark-haired guys in suits and three-dark haired women in dark jackets and pants. I watched four episodes and still couldn’t remember people’s names.

Now look at this:

Which group do you want to know more about?

3. Once you have your group members, you have to introduce them to the reader. Carefully. The easiest and clearest way to do this is to introduce the characters one at a time, establishing each of their personalities and their relationship with the leader before moving on to the next. Red builds its team that way, the Scooby Gang was introduced to Buffy one at a time, the Machine Gang began with only Finch and Reese. Or you can bring several of them together in conflict and under pressure, and watch them demonstrate who they are and what they bring to the table as the team hits the ground running, as in Leverage where the different characters are hired for one job and become a team under the leadership of Nate Ford, motivated by a joint desire for payback.

However you introduce the members, it’s important to establish their differences up front, especially their skill sets, their personalities, and their flaws and weaknesses. The “You complete me” trope that’s so awful in romances is actually good in building communities; each member is a part of the whole and without each member the whole is incomplete. That means you don’t want any duplicate skill sets. I’m a huge Person of Interest fan, and I love the characters of Reese and Shaw, but they’re duplicates; if the team loses one, the other can do exactly the same things so the whole is not diminished. But if that team loses Finch or Fusco, there’s a hole there that’s not easy to fix. It’s one reason the team is still reeling from the loss of Carter: she was essential.

The same goes for personalities: Friends‘ control freak Monica, material girl Rachel, free spirit dimwit Phoebe are impossible to confuse, as are smart but doofus Ross, tricky Chandler, and sweet dimwit Joey. (Yes, that’s two sweet dimwits, but one’s male and one’s female, so that helps a lot.) The point isn’t just to make sure they’re all different, the point is to make sure they interlock to make the community/team stronger than the sum of its parts. Monica without Rachel and Phoebe would be an uptight mess living a tidy but dreary life; Rachel without Monica and Phoebe would be broke and immature and living with her mother; Phoebe without Monica and Rachel would be wandering the streets singing “Smelly Cat.” They really are better together.

4. Once you have that community established, the fun begins. In the same way that conflict shapes and arcs a protagonist, so conflict shapes and arcs a community, but in infinitely more complex ways because within the community, that conflict is also sparking individual character change. That means a dynamic community is constantly reinventing itself, moving like a series of gears as each character changes and in turn changes the others; everybody has to accommodate everybody else or the community breaks apart. You may have to establish those community members as cartoon-simple in the beginning, but the moment the community begins to act, the characters of its members become more layered, their complexities made evident because of their interactions on the page.

But that’s just the surface stuff. There’s a lot more that I want to know about how community works in storytelling, so for the next fourteen weeks our give-me-something-to-watch-until-this-nightmare-winter-is-over TV Sundays series is going to be Leverage, a show about a group of criminals led by a former insurance investigator who band to together in a kind of Equalizer Club to help the helpless and kneecap the predatory.

If you want to play along, all five seasons are streaming on Hulu, Amazon, and Netflix. My tentative plan (everything is subject to change) is:

Feb 23 “The Nigerian Job,” by John Rogers & Chris Downey (1-1) Introducing a Community

Mar 2 “The Juror # 6 Job” by Rebecca Kirsch (1-11) Integrating a Single-Character Subplot

Mar 9 “The First and Second David Jobs” by John Rogers & Chris Downey (1-12/13) The Recurring Nemesis

Mar 16 “The Beantown Bailout Job” by John Rogers (2-1) Community Dynamics

Mar 23 “The Two Live Crew Job” by Amy Berg & John Rogers (2-7) Foils and

Doppelgängers

Mar 30 “The Jailhouse Job” by John Rogers (3-1)

Apr 6 “The Inside Job” by Geoffrey Thorne (3-3) Integrating Single Character Back Story

Apr 13 “The Rashomen Job” by John Rogers (3-11) POV

Apr 20 “The San Lorenzo Job” by John Rogers & M. Scott Veach

Apr 27 “The Lonely Hearts Job” Kerry Glover (4-15) Integrating Romance

May 4 “The Radio Job/The Last Dam Job” Chris Downey & Paul Guyot; John Rogers (4-17/18) Beginnings, Endings, and Call Backs

May 11 “The Broken Wing Job” by M. Scott Veach & Rebecca Kirsch (5-8) Character Arc

May 18 “The Frame Up Job” by Geoffrey Thorne & Jeremy Bernstein (5-10) The Homage

May 25 “The Long Good-bye Job” Chris Downey & John Rogers (5-15) Endings

Leverage is a lot of fun: it’s light, it moves fast, it’s not depressing, I never feel the urge to slap the protagonist, and it’s a great vivid, dynamic community. It’s the closest thing I could think of to sunshine and tulips until the real things arrive. (Okay, that would actually have been Pushing Daisies, but a good vengeance plot always makes me feel warm and sunny, so we’re going with Leverage.) If you’re not familiar with the show, this YouTube video gives you all five seasons in three minutes.

Questions? Suggestions? Complaints? Put ‘em below.

Note: The first season episodes were aired out of order (why do networks DO that?) so if you’re catching up on the entire first season, here’s the intended order of the episodes with the ones we’re watching in bold:

Nigerian (1), Homecoming (2), Wedding (7), Snow (9), Mile-High (8), Miracle (4), Two-Horse (3), Bank Shot (5), Stork (6), Juror #6 (11), 12-Step (10), First David (12), Second David (13).