Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 8

September 27, 2019

Chapter 2

No meant so.

Photograph: Krzysztof Grech

Photograph: Krzysztof Grech“When I look at him my ovaries start singing, please take him away from me, please,” she said to her friend Anu who was trudging alongside Simmi in the baked hot sand.

The two women were spectacularly failing the Bechdel test under a soft pink sky flush with a scent of neutrality.

Simmi was not afraid to love him but she was aware of its consequences.

Their bodies tilted sideways as they walked. Swooning was not the same as succumbing.

Simmi rolled her eyes and turned away to the blazing orange orb setting in the sea. She squinted and tried to concentrate on the green spot that appears right before it disappears.

He made her feel proud of her childbearing broad hips. She did not want to go down that road at all. She had decided long ago that motherhood was off her map.

What would have happened if she had professed her love to him? He would probably accept her proposal. They would get married. And then? For a few years she would be able to delay the good news announcement, following pressure from family, friends, peers, who all wanted the same thing out of them.

They would have decided against it in their prenup vows. No meant so.

She had to be sure that he would not succumb to the pressures. Two were a family too.

Her phone rang. It was him. Just like the movies criticised for failing the Bechdel test spectacularly.

She looked at Anu and smirked. “I have two options. To take this call or,” she pointed at the waves.

Before Anu could react, Simmi said, “Here, take the call and tell him I am drowning in my amniotic fluid. He will say what? Take a pic and send it to him.”

She began walking towards the spumy waves, lifting her white skirt, trying her best to stay dry as far up as she could, and that’s just one way of looking at it.

Anu spoke to Shahnawaz as she watched Simmi frolic.

“What did he say?” Simmi asked, returning to wear her slippers.

“He said he will get a vasectomy.”

They laughed. It had a conspiratorial ring breaking the silence of the neutral air.

They knew him so well. That charming rake.

Simi took a long deep breath and said, “How can I resist him? I think am already wet.”

They laughed again. This time it was for Simmi’s irreverent candour.

They got up to leave as the sun drowned and the birds began to scatter to their nests in a hurry.

Shahnawaz would have laughed too, Simi thought, calculating what he said when he was told she was riding the waves.

Photograph: Max Dupain

Photograph: Max Dupain

September 21, 2019

Chapter 1

No time to die.

Paul Newman, unbuttoning.

Paul Newman, unbuttoning.A love story should be epic, he said.

One of us has to die for that, I thought. Who better than him to kill me? Here he is, standing in front of me, asking me to take my shirt off and wear his in exchange. I want to shut him up with a kiss. I feel flushed like Hugh Grant in Notting Hill.

Why? I ask.

Because I am going to a party and my shirt is dirty, he says.

A gust of wind blows in my face. I am not convinced but I want to believe what he just said. He wants me. Up till now, only I wanted him. It would never have occurred to me that he would want me some day. And today, when I am leaving, he is missing me already.

We are both wearing exactly the same black shirt. His looks spotty but it fits his chiseled body better than my loose fit.

No, am not stripping in public, I say, shy that sitting on this crowded bench on the railway platform I should flaunt my unfit body to stun the approaching train.

He shrugs and smiles because he is not easily defeated. We are interrupted by the train’s bells and whistles. It will stop here for only a minute. We have to be quick.

We enter the compartment and find my seat. It is time for goodbye. Not in the traditional way, when a woman and man kiss. A goodbye kiss is like a postal stamp for the goods being shipped that will return one day because it was addressed to the sender. I don’t know why I thought of that sentence. My mind is distracted.

He steps out and looks at me through the window grille. That gorgeous face cropped with shiny curls and a smile that is launching this very train is worth a black shirt. I have the sudden urge to remove it and toss it at him. The shirt is now an umbrella of cute thoughts.

I know he wants to wear me as much as I want to wear him.

But longing will keep us alive. Possessing each other through the shirt might complete us and bring this story to an abrupt happy end. It won’t be epic anymore. We have to be separated for that. That is how love stories become legendary.

I sit back and suck grape juice from a tetra pack. That feeling is just beginning to be realised. He loves me. I have seen his handsome face smiling and waving at me as it fades in the distance. He has not said it but I have felt it. If I have to die, let this separation from my lover kill me. The juice box begins to shrink. It is dead from the inside.

Unknown model, unbuttoning.

Unknown model, unbuttoning.

September 18, 2019

Udit Narayan: An Ear for Music

The rumour was of his first wife’s return.

It was in the summer of 2004 when Deepa got a pissy whiff of rumours circulating around her neighbourhood that Udit was spending quality time with another woman somewhere in the interiors of Bihar, his hometown.

The other woman was said to be his first wife. Who would believe that Udit was capable of infidelity?

Deepa’s best friend said he was sweeter than sin. That made no sense to her. Deepa thought of his patsy grin. Was he really that sweet?

She was not going to take things lying down. She sat upright in bed when she heard about his mistress.

Udit’s parents travelled from Kathmandu to his deluxe penthouse in Mumbai to be a part of his nineteenth wedding anniversary celebrations. Deepa had specially asked for them to be present so that she could put things in perspective and end the matter there and then.

Their son, Aditya, who in the past could never stop fawning around his dad, ‘Oh, I love you Daddy,’ a refrain he sang with his father in Akele Hum Akele Tum as a child artiste, had, after the whispers in his college, started avoiding his very likeable father.

A man with such an unblemished, spotless reputation had to have a secret behind his now ridiculous looking everlasting grin. How Aditya hated this man, he made it a point to reach home awfully late for dinner every day.

Udit, aware of the growing suspicion, also tried to avoid the messy situation at home by excusing himself with busy schedule, late recordings, stage shows, etc, etc.

‘You know how busy an artiste’s life is,’ he grinned.

Deepa was supposed to sit at home, apply different shades of fuchsia nail paint on her toes and move on.

For the evening, Deepa draped a stunning Newari saree in black silk with sanguine red patta border and wore pale gold teardrop earrings from a previous wedding anniversary gift.

At the family dinner, conversation was polite, peppered with salt and pungent dalle khursani (chilli). The momos, Udit noted, were splendid, comparing their soft texture to Deepa’s dimpled cheeks, but Deepa kept a poker face in front of her in-laws.

After her in-laws had retired to the guest bedroom, Deepa took to her bedroom, hoping to have a lengthy discussion with Udit on the state of his current affairs. Noticeably, the one involving another woman, for which she was contemplating separation.

She had spoken to her in-laws, and they had advised her not to be so fastidious and sort it out with Udit, at every doubt assuaging her that their son was a ‘bhadra hridaya bhayeko sant jasto maanchey’ (saint with a golden heart).

Udit walked into the bedroom, holding a gift-box that he was going to present to her, but the petulant woman railed against it.

“Chaiyn dei na timro gift haroo, ko cha tyo aarko… timro rakhel!…(don’t need, your gifts and all, who is that other…your keep!)” Her throat enflamed with anger.

“Yo (this),” pointing to the gift box, Udit untied its frilly lace saying, “Ek chhin (one moment),” he placed a CD in the music player on her dressing table.

Before it could play, he gave her an intro, “Yo geet mai le timro laagi especially aaj record garre; hamro laagi. Sab kura afwaa ho, kina bhaney ma yaahin chhu timro saath, timro laagi, sadhai yethai chu, timro sau” (This song I have recorded today especially for you; for us. All talk is rumour because I am here, with you, for you, forever present, I swear by you).

The song from the yet to be released film Veer Zara played.

‘Jaanam, dekh lo, mit gayi dooriyaan, main yahan hoon yahan hoon, yahan hoon yahan…’

Karaoking, he walked towards her, “Ma yahin chhu, yahin chhu, yahin chhu, yahan.”

She controlled her smile, puckered her mouth.

He placed his hand on her shoulder singing, “Kaisi sarhadyen, kaisi majbooriyan, main yahan hoon, yahan hoon, yahan hoon, yahan.”

The Narayans: Deepa, Udit and Aditya.

The Narayans: Deepa, Udit and Aditya.Then the song interlude of Mera Laung Gawacha played, and Deepa was instantly reminded of her wedding night, when henna-hands she danced riotously. She felt like doing the same at this very moment. Udit was taking her back in time, a time when they were younger, and no one could have come between the two lovers.

‘Tum chhupa na sakogi, main woh raaz hoon, tum bhula na sakogi, woh andaaz hoon.’

Deepa was soon going to melt, if this continued.

Udit held her hand and led her to their canopied bed dressed in sheer white gauze fabric, rose petals littered on the purple satin sheets. He held the back of her head, his lashes fluttering in the scent of her perfumed tresses. She was like soft chhurpi (yak cheese) in his arms.

His fingers trailed over to her chest as he lay beside her. ‘Goonjta hoon jo dil mein toh hairaan ho kyun…Main tumhaare hi dil ki toh awaaz hoon.’ Her heartbeat rose, a quickening velocity she could not breathe through.

‘Sun sako, toh suno, dhadkanon ki zabaan…Main yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan.’ He put his ear to her bosom.

She turned to hide her face, she was beginning to soften, and was feeling ticklish like the plucky virgin she was on the night of their wedding.

‘Main hi main ab tumhaare khayaalon mein hoon…Main jawaabon mein hoon, main sawaalon mein hoon.’

Deepa began to submit to his advances, there was no easy way out; she could not give up on this man, this melodic enchanter. Her body was now ready to be his.

She had fulfilled so many of her dreams with him. She could overlook his indiscretions if he had some, and women were born to be martyrs, wasn’t she?

‘He is a star,’ she thought, ‘People will throw themselves at his feet. So what if some harlot gave him a moment’s pleasure in some poor, unlit village in her absence.’

What mattered to her is that right now he was with her, in her bed, their bed. The lyrics were gas lighting her spirit and dulling her thoughts.

‘Main tumhaare har ek khwaab mein hoon basa…Main tumhaari nazar ke ujaalon mein hoon.’

Her eyes had begun to dilate.

‘Dekhti, ho mujhe, dekhti ho jahaan…Main yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan.’

‘Oh yes,’ she began sliding into a trance, a sleep, as Udit stroked her eyelashes with his palms. She was rising into a dream, or truth was a fairy tale world to sew into her sleep.

As Deepa sauntered off into another realm, she could hear Udit’s mellifluous voice echoing in the distance, ‘Main yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan hoon, yahaan…’

Deepa had dozed off.

Udit walked into his bathroom, dialled a number, and spoke sternly to someone not to contact him for some days till he got back. He hummed the mukhda of the song, washing himself, readying for bed.

It occurred to him to change the ringtone on his cell phone, the only way to keep Deepa’s malleable sanity in check.

He walked over to the CD player, replayed the lilting track and held his mobile phone close to the sound box as if it was an ear that needed to be hypnotised.

https://medium.com/media/5bd52eaff4d0f913548177346a27221b/href

September 7, 2019

Asha Bhosle: Music of the Heart

‘You have never let me live peacefully,’ she sang to her sister.

Lata was always sore with Asha for having once eloped with a young lover.

She thought it was Asha’s way of getting back at her for not being attractive to men.

Asha was, of the four sisters, the most beautiful, and her yet untapped voice, bordering on sultriness, added to her allure. Asha knew how to use it to her advantage, though she was relegated to singing for vamps, molls, licentious women — hanging in the shadow of Lata didi, whose holier-than-thou image was more spectre than shelter.

When word got out of Asha’s affair with the hot-headed music composer O P Nayyar, Lata spoke to the press about it in unkind words. Nayyar, who had never worked with Lata, decided against it in the future. He was so incensed by Lata’s misgivings that he torched the magazine that carried her interview with his cigarette lighter and stubbed the cigarette butt in Lata’s poultry face, complaining about her matronly clucking.

Asha who was sitting next to him, startled and numb to react, witnessed the charring of didi’s face on the cover of the magazine as a horror she would never wish for but nervously laughed off to lighten a visibly irate Nayyar. She made no attempt to stamp the fire out with her thick-soled sandals. It would look like she wanted to kick didi in the face for interfering in her love life again. The last time she eloped with a man she was in love with, their marriage was an eventual failure. Lata had accepted her back into the house with an iron fist.

Nayyar who was young and brash, and with Asha, younger, and impressionable as his gypsy-hearted muse, he was going to make the best of their unlikely combination — spiralling Asha’s fortunes in the musical firmament with heady cocktail solos dipped in high spirits and whipped with the cream of an uninhibited, feline wantonness that only Asha could evoke.

With the evolving taste of the music scene in the sixties, where affluence was emerging, and where women were beginning to desire, and express as much as men; at least in cinema, where dreams could uncork bottled aspirations, Asha’s perfumed voice emanated from Radio Ceylon, chasing jazz music and blue smoke, twirling them around in a magical vapour and creating an ambience of decadence and sin.

Her vocals provided room service to darkened bedrooms lit by lamps draped in vermillion red or green scarves. It made people horny and hopelessly happy.

Screen goddess Madhubala’s tantalising ‘Aiyye Meherbaan’ or the peach plump Mumtaz’s ‘Yeh Hai Reshmi Zulfon Ka Andhera,’ to Babita’s whisky induced hiccup ‘Aao Huzoor Tumko’ and Asha Parekh’s balmy ‘Jaiye Aap Kahan Jaayenge’ were as much about temptresses effortlessly wooing men into their pleasure domes as it was for Nayyar and Asha taking off to colonial hill-stations to compare evocative notes.

What was evident from these songs and their sporadic rise on music charts was that Asha had become Lata’s sensual voice and it began to worry Lata even more. Her sister had become her rival. Nayyar’s music had helped her attain stardom, but not without its pitfalls — where were the Filmfare awards in recognition of her collaboration with Nayyar?

Lata decided to confront her debauched sister, or she thought that such trendy songs had made her so. Nayyar and Asha were making music for twenty years and yet there was no sign of a marriage. What else could all this lead to? She had never discussed it with Asha before, but now, she was upset and concerned.

Asha lived across Lata’s Peddar Road apartment. Lata could have walked into her house anytime she wanted, and had Nayyar seen it, he would have quipped as symbolic of the matronly chick crossing the street. Lata decided to take Nayyar into confidence and spoke to him in his studio.

‘Asha and me, we were inseparable. I used to carry her with me to school. When the headmaster said I could not get my sister into the class for the admission of one, I decided to forsake education. I have not spoken to her in many years, and you are the reason, you know that well. What will it take for you to return my baby sister, my Asha to me?’

Nayyar sat still in his chair, Lata standing over him, casting a nebulous cloud over his thoughts. She looked like she was auditioning, the mike missing in front of her, but her nightingale voice smoothly creeping into his heart and melting it for her wispy agony.

It was really that simple.

Asha Bhosle.

Asha Bhosle.A film poster of Pran Jaaye Par Vachan Na Jaaye was framed on the wall behind where Lata presently stood. Nayyar, whose eyes were fixed on the poster for which he was composing, and in the midst of wrapping up the last song, stood up, said, ‘You have my word,’ and opened the door for the nightingale to make a graceful exit.

The nightingale, without whose singing ability, he had made a name for himself. Without her younger sister’s talent, love, and support, could he have made it? Was he the only reason for rift in this doting Mangeshkar family?

A few days after this secret meeting, Asha came to the studio to record the last song for the film. She was surprised at its dark, introspective mood, and a complete departure from Nayyar’s signature style. The song recording was no fun either.

Nayyar scolded, shouted and insulted her in front of the musicians, cussing that she was not capable of modulating her voice, why did she have to sing like a nympho all the time, where was the poetry, pain, pathos?

Perplexed, humiliated, after many retakes, in which Asha felt her heart bleeding, her voice sunken, she sang to give depth to a song about irritability — drawing from her reserve of resilience she had hardly exercised in all these glorious years.

It was no test. Without giving her any reason, Nayyar split with Asha. That day, when a harried maidservant who worked at both the sisters’ houses brought Lata the news of Asha’s break-up, Lata ran across the street to console her little one.

The year after, at the Filmfare awards function, Asha was no longer competing with Lata. Asha was nominated for four songs. Suman Kalyanpur received the fifth nomination but everyone knew it was Asha’s night. She was touted to win for her zinger track for Zeenie baby, ‘Chori Chori Solah Singaar’ in Manoranjan — where Zeenie, but obvious, essayed the role of a gold-hearted prostitute.

After the five nominations were played out by a live band on stage, Lata boisterously announced the winner, ‘And the Filmfare best female playback award goes to my Asha for Pran Jaaye Par Vachan Na Jaaye.’

Asha was stung in her seat. Usha and Meena, her other sisters who were flanked on her sides began hugging and kissing her, prompting her to stand up and walk towards the trophy.

She stood up like an upright column, dressed in a pristine white organza saree, pearls shining around her neck, her sartorial best. She didn’t know if she wanted to walk up, or turn around and head towards the exit. She faltered.

From the stage arose a pianissimo of the woeful song she has won for. Who was she miffed with? Nayyar, or her seemingly cheerful didi? The sombre song was timed to play till she reached the stage.

The song being, ‘Chaen se humko kabhi, aap ne jeene na diya…’

https://medium.com/media/58cadd303ee1d6b0bfcf37f566ce0c13/href

August 29, 2019

Sisters Of The Sufi Order

Rekha, Kavita, Ila, Jaspinder, Richa, Sapna and the seventh one missing.

Rekha Bhardwaj.

Rekha Bhardwaj.Despite singing for all the major music composers in Bombay, Rekha Bhardwaj was upset that none had dubbed her the most soulful Sufi singer in the country.

That was because everyone in the fray was elbowing for the top spot.

Kavita Seth, Ila Arun, Jaspinder Nirula, Richa Sharma, and even the near-forgotten Sapna Awasthi.

All of them had sung Khusro and Rumi–inspired compositions and thought no less of their claim for the trophy.

Rekha decided to call for a singers’ coven in which Rumi himself would decide who amongst them was the best in the business.

A tent was set on the grounds of Hanging Gardens. Draped in black shawls, the gathered women settled in a huddle, to hold hands and call for the spirit of Rumi — the Illuminated one.

Rumi appeared with very little effort, his eyes shining with the brilliance of a man who had arrested stars in them. Doesn’t take much to please him; the sight of such a talented bunch of aggravated women was surely something to soothe his nerves in these trying times.

Rumi: “Hmn, so what will it take to prove that one of you is the most sufiana?”

Rekha was the first to contest, “Ghar jala liya hai…” in her sonorous voice, sullen in distress.

Richa quickly butted in her high-octane pitch, “Teri kaali ankhiyon se zind meri jaage,” in a bid to impress Rumi.

Sapna Awasthi, sensing her elimination and feeling threatened that she was not going to be considered, screeched, “Kuwa maa doob jayoongi.”

This was not going to go down well with the doyenne Ila Arun, scrimping, she grated her betel stained teeth and taunted the upstarts, “Nigodi badi harami hai… jo baat sunne na meri…nigodi!”

Embarrassed at the cat fight which was about to take place, Kavita Seth shyly raised her voice of dissent in her low timbre request, “Oh re Manva, tu toh bawra hai,” hoping that her quiet resignation would earn her some brownie points with Rumi. She had recently recorded an album called Sufiana.

Jaspinder decided to take a defeatist view of the matter, yodelling, “Yeh toh hona hi tha…” summing up the competitive mood of the gathering.

A long silence followed Jaspinder’s trilling endnote.

Rumi spoke, “Your bickering reminds me of my youth, when I walked all the way to Damascus in search of my master Shams-E-Tabriz. Why was I looking for him when he was not there? His essence was in me. I was looking for myself. I cannot help you ladies, go back home, your search is pointless till you surrender to it.”

Dispirited, the women walked downhill into the pall of the twilight hour, not sure if Rumi had given them a sign.

They walked into a teahouse and were sipping from their cups when they looked up at the breaking news update on a telly screen mounted on the cash counter.

Some days ago, a certain curly -haired stout woman in Pakistan, visibly shaken at being accorded the Best Living Sufi Singer in the World title had screamed ‘Jalal’ (meaning glory, anger, dignity and the first name of Jalaluddin Rumi) and walked out of the back door of her house.

Covered in hijab, she is said to have glided through a busy market square and headed to the surrounding mountain range. She has been missing ever since. She is said to have renounced the world.

The six women seated at the table took an unspoken pledge. Holding hands yet again, eyes shut, they nodded to walk out in all possible directions in search of that missing woman — far and wide they would traverse, as dervish women circling the universe in their flowing robes.

It was the only way for them to come home to themselves. That missing woman was Abida Parveen.

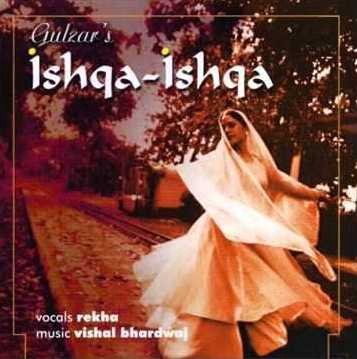

https://medium.com/media/5f2df8ec7ffb2ae4e0ae7aeea2ed6b5d/hrefTrivia: In December 2002, Rekha Bhardwaj released her seminal music album Ishqa Ishqa — lyrics by Gulzar, music by Vishal Bhardwaj. Ghar jala liya hai is one of the tracks from the album.

August 26, 2019

Pritam: Music In My Head

The composer was bald. A song cured it.

‘Alopecia Universalis,’ the rapidly-blinking doctor announced, chafing his front teeth over his lower lip, as if waiting for a solution from the people he was talking to.

Across him, Pritam, seated with his father, looked lost in the doctor’s choice of words.

Prabodh Chakraborty petted his boy’s glistening well-oiled head one more time, and darted a glance at the doctor, ‘Abaar key ta hobay, bolun toh dada (what will happen now, pray tell brother),’ he raised his left hand in the air, curling his fingers to shape a question mark of uncertain fate.

Doctor Sen drew his shoulders to his ears and resigned, ‘There is no standard treatment but I will prescribe and we can see results from time to time. This situation could be a short-term body change, condition can come back to normal, but when, that is the question!’ he said.

At age fifteen, Pritam realised something was different about him. One day, when he was peeing in the stalls in the school’s toilet, some boys his age ambushed him and laughed at his genitals.

One of the boys shouted in a fit of hysteria, ‘The crackpot must be shaving his dick too, what’s he thinking, he wants a smooth pussy maybe!’

There was a huge uproar of consent in the disinfected environment. The boys had pulled at his trousers and interrupted his relief time. He puttered as he buckled and escaped further humiliation.

Unlike the growing boys at school, he had no use for a razor.

He was a hairless wonder whom the children at his father’s music school often teased for looking like an alien. He didn’t mind them, he taught them how to play the guitar, hoping someday he would make it big as a musician and then it wouldn’t matter how he looked. Girls, he knew would come, once the money poured out of the hollow in his guitar, to the strum of his sore fingers.

When Aditya Chopra, heading Yashraj Productions, signed Pritam for Dhoom’s score, the grand old man of romance, Yash Chopra flipped, ‘Kya Adi, iss bacche se music, abhi toh iske sarr par baal bhi nahi ugge hain.’

Adi offered Yash a lopsided grin that the paparazzi waiting outside the fortified studio had been praying to capture for years.

It is when the track Dhoom Machale was being composed that there was a paranormal activity Pritam began to notice in his body. Each time the music boomed on the sound system in the recording studio, he would begin scratching his baldpate and would feel a strange sting in his groin.

Since Sunidhi Chauhan was singing the song on his cue, he thought her voice was stirring his loins; her gruff throw, her westernised accent, her squeaky clean good looks across the glass pane from his mixing board.

He fingers began to fidget over the arranger, synthesiser going out of control.

Sunidhi predicted the number would be the chartbuster of the year. She patted his cheeks, smiled, and gave him a friendly peck on her way out. He couldn’t understand what he had made of the music that night; his fingers had not worked in sync with his mind as they performed on their own free-wheeling accord, while all he wanted them to do was scratch his head and balls.

He woke up next morning to find a single jet black strand of hair on his head, right in the centre, like a wisp of smoke zigzagging its way out of a brown chimney.

He laughed, he laughed so hard he thought the mirror would crack in fright as he kept beating on it to alarm himself. He pulled the band of his pyjamas away from him to check if there was a growth down there too. He touched himself as he shunted wild thoughts in his mind.

Was it the music? That song? Dhoom Machale?

Could music be the cure for Alopecia Universalis?

Yes, some plants are known to respond, but does that mean his body so long was in a vegetative state to his talent as a musician?

‘This is something original,’ he skidded.

‘Original as my music,’ he beamed.

He called up the studio that morning and cancelled his sittings. He roamed the house, naked, downing blinds and pirouetting to his original composition, hopeful that with each replay Dhoom Machale would sprout new wonders on his hairless body.

There was no instant cure.

Pritam got back to work, disheartened and even more busy churning music to ward off all therapy from it. Tunes were being shuffled in minutes, films being signed in card packs. Hit songs were being churned out like fast-food burgers.

Pritam had no time to even look at himself in the mirror, last of all face the dejection that he was in his image, a personality he wanted to shatter with his success.

Dhoom Machale became a rage.

Such was its impact that everywhere Pritam went, it was the only song being blasted; at weddings, at Ganpati immersions, Diwali crackers whistled the tune, ring tones screamed the song, vehicles had replaced their horns with it. Pritam’s music was in the ether as well as reaching into his nether.

But he wanted so much to get away from Dhoom Machale’s spectre following him around like his shadow, a macabre presence he wanted to shirk, too much play had rubbed the novelty of the song.

Dhoom Machale had become anathema to his ears.

After appearing as a judge on a singing competition reality show, Pritam took a break on the weekend and headed to Mahabaleshwar for a weekend trip of some peace and quiet.

Sunday morning, lazing in bed, he switched on the telly in his cosy room overlooking Sunrise Point, and began watching with no particular interest when flipping through channels he came upon the show he had recently shot for.

As the compere announced his name and the camera panned to the flowered entrance on the stage, in walked Pritam, hands folded in a namaskar.

‘Grinning like a bear’ he thought, but wait, there was more — hair was oozing out of every pore of his body. He was covered in it from head, to covered toe.

‘There is more hair on me than snow left on Everest’s peak,’ he blurted at the irony.

He swore he could see spurts of hair fizzing out of his ears. It was that much music to take.

Dhoom boom it was.

‘Success,’ he wryly thumped on a pillow and muttered, ‘has made me unrecognisable.’

https://medium.com/media/334cae3847322caec5e02084d112a7a0/href

August 24, 2019

A Call From The Past

Photo Credit: Shome Basu

Photo Credit: Shome BasuThe other day, we were walking in the filthy streets of Bowbazar, despairing for the women to be working in such appalling, unsanitary conditions.

As we waddled through narrow lanes covered in monsoon slime and moss, edifices shaky, toilets dank and dirty, and a bazaar of noxious scents assaulting our nostrils, I asked my guide if these quarters were once the balakhana (kotha) for mujras.

She said it was unlikely, only sex-work thrives here.

So I said there must be someone here who wants to sing and dance.

She said I was being a tourist.

I stopped walking. I heard a sound; an answered prayer revealed itself above my head, in the leaky tenements we were crossing.

It was the rhythm of ghungroos tied to a girl’s unshackled feet.

Can you hear that? I asked her to stop and listen.

She did.

The music stopped.

She walked.

The rhythm picked up where it had left and walked with me.

The girl is practising, I thought, or is it me hearing the muffled sounds of my unbidden past?

August 17, 2019

Gulzar: The Memory of Weight

A mahogany chest holds his beloved’s kuch saamaan.

He was walking behind her in a straight line, trying not to swing his gaunt hips.

He called out, “Sunoh, zara yahan aana.”

She turned around, her anklets swerved to deliver a stuttering sound. She dropped her shoulders, putting weight on her hips; a sign of both acceptance and disdain. She walked towards him. He looked at her, tilting head to make way past her long, curled lashes.

He groaned, “Kya bhar diya tumne iss sandook mein, bahut wazan hai, utthaya nahi ja raha. Kya hai isme?”

She put a dark hennaed hand on the weight of the luggage to cause a depression on his hunched shoulder and with little sympathy for his agony, her voice ironic, she said, “Mera kuch saamaan.”

That very instance, Gulzar was stirring his evening tea in his bungalow Boskyana. Alone, stretched out on the rattan in the balcony, and dissolving brown sugar in the cup, his seat was overlooking the security gate that was unlocked and unmanned.

He looked vacantly pass the gate into the deserted road ahead. He decided to wait for the tea to cool. He felt heavy, displaced. He couldn’t devise a mukhda for the tune he had received from music composer R D Burman, having played it repeatedly on his recorder all afternoon. He hadn’t taken a nap after a sumptuous lunch of muri ghonto, bhendi bhaja and fragrant gobind bhog rice.

He decided to take a nap and left the tea in a whirlpool. Maybe a dream would help.

He sat by his bed and stared at the mahogany chest in the corner, the key to which she had taken along. He wondered what she must have left in it. Why didn’t she leave the key with him? Didn’t she want him to open it and ferret through her personals? How else would he describe her if not for the perfume trapped in her chest?

He caressed the padlock in one hand, and like a sleepy child lay down alongside.

एक इजाजत दे दो बस

जब इस को दफ़नाऊँगी

मैं भी वही सो जाऊँगी

https://medium.com/media/b75ac99155f12c149501f381c975bf8a/href

August 15, 2019

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: A Circular Rhythm

Passing the musical baton to Rahat Fateh Ali Khan.

extreme left: little Rahat, centre Nusrat, on harmonium Farrukh.

extreme left: little Rahat, centre Nusrat, on harmonium Farrukh.‘I think the noise is coming from here,’ Nusrat placed a swollen palm on his heart, reaching out to his band of musicians who had filed into his hospital room, anxious of his critical condition.

The men were weeping and pleading for Allah’s mercy.

His words silenced them. Like dutiful apostles, they circled his bed to pay attention. It was both a time of grief and challenge. Nusrat was dying, and yet, on his deathbed, he had the most difficult task to execute.

From amongst the men gathered in the room — Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Mujahid Mubarak Ali Khan & Party, he had to choose his successor. Mujahid, his first cousin, Farrukh, his brother, Rehmat Ali and Maqsood Hussain were the front-runners for the post. Nusrat’s pupil, chorus boys, mandolin player, percussion, and harmonium ustaads were also present in the room.

‘Twenty three years ago,’ Nusrat rewound. No one sighed.

‘When I was sixteen; a sixteen year old who had no passions, my waalid’s (father) death gave me a purpose in life. I had trained with him, on the tabla, and learnt the classical khayal form. At his gravesite during his chehlum (fortieth day memorial) ceremony I gave my first performance. I looked up at the skies and sang as I watched a faint star blinking and approving. I knew he was blessing me. I had found my calling, I had found my voice. ’

Nusrat paused to observe the eyes of his singing men glazed with tears. ‘I was twenty-three when I took over as lead singer of my father’s qawwal party. It’s twenty-three years since then and the decision is not easy. All of you are very dear to me, and I will pray that you achieve more success without me.’

‘My brother here,’ he continued, ‘Farrukh, who I believe is more talented than me, is not going to succeed me.’

No one shifted. Not one deceived Nusrat’s opinion.

‘And I have reason to say so, Farrukh will agree.’

Farrukh moved forward to hold his hand.

‘With me, a little of Farrukh will have died too. He cannot take over. I know that. Our music, our devotion, has to be renewed with new blood, a young heart pure in its quest for the Sufi way. Farrukh, and me, we have grown old in the tradition, our hearts are weary and these modern times require even the old art forms to be reignited with a new, brighter flame.’

‘In you,’ he addressed the rest of them, ‘there is one amongst us now, who is paak, as pure as mousiqi (music). It’s him, who is not enlightened, this path, will show him, this discipline to Sufi tradition. If we do not elect him now, we will distance him further from his destiny.’

Rahat with father Farrukh on harmonium.

Rahat with father Farrukh on harmonium.Nusrat cleared his throat to announce his candidate.

‘Brothers, do not be slighted by my decision. It is a sacrifice I am making, and you will have to see it as that. Some of you have reached a stage where you are mature to lead, but I cannot see myself putting your head to sacrifice. I should offer my god son’s head, as Ibrahim did. I can only wish for Allah to show mercy on his test of my faith. I offer him my little lamb.

With that, a smile appeared on his puffy face. He raised a hand in the direction of Farrukh’s son, gesturing him with a head nod to come seek his godfather.

Farrukh’s tears began to roll down his pallid cheeks uncontrollably. Nusrat had raised the bar by picking out his unpolished son for the mighty post.

A shy, young man, startled by this knighthood, the gravitas of which hadn’t sunk in, lowered his head before his uncle to kiss and bless him.

At Nusrat’s chehlum, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan sang, Gin Gin Taare Lang Diyan Raataan. He had sung it first on stage at a concert in England; a solo Nusrat had coaxed him into performing for an audience that was not entirely convinced of his fledgling falsetto. He was eleven then, and his uncle’s pat on his shoulders was reassuring.

Today, at twenty three, when Rahat improvised his sargam, going sotto voce at times, he would look up at the dusk sky arranging its stars; they played out, sparkling and dimming, responding to his dip and scale like musical accoutrements.

https://medium.com/media/4942eb10a888a9bed1ebed73ac7add73/href

August 14, 2019

Adnan Sami: Music For Chameleons

Elevator music can be uplifting, say Lift Kara De.

Adnan Sami

Adnan SamiThe rumour had spread like street hawkers in the busy shopping district of Lokhandwala.

Neon lights glowed brighter, and as far as you could see from the entrance, right up to the end of the lane, the bustle cheerfully welcomed its newest resident.

The real estate network was buzzing with a new development in the market.

Every firm on this side of the Mithi river wanted to accost singer-composer Adnan Sami. They had lucrative deals lined up for the gifted musician from across the border. Adnan Sami was shopping for a flat in Lokhandwala — the home of has-been Bollywood celebs.

One canny builder, sensing the opportunity, pulled a few musical strings. He was selected to chaperone Adnan to his majestic under-construction tower.

When he met Adnan, he was in for a rude shock. Not having expected Adnan to be a man of his size, he wondered how he would fit all of Adnan into an elevator to escort him up to a penthouse in the tallest building in the vicinity. He shuddered, and showed Adnan his less commodious apartments, vexing a plan.

Adnan was not impressed by what he saw and kept asking for more room, more space, more air.

‘Can’t you tell by my size?’ Adnan joked.

‘Yes sirrr, but sirrr, ok sirrr,’ the poor builder servile in his manners, tried to placate his client. ‘Ek din aur Sirrr, you vill not be dis-aa-aa-appoint.’

Next day at noon, Adnan was ushered into a spacious elevator. The builder had politely excused himself out, signalling at a green leather chair inside, bowing and gesturing Adnan to take a seat. As if it was going to be an awfully long journey into space.

When the elevator moved up, an instrumental version of his recently released hit song Lift Kara De played inside. Adnan grew suspicious. He hated people who made an effort to please him.

The elevator opened on the fiftieth floor, into a living room decorated in baroque fittings. Heavy silk drapes hung, which he moved to take a view from the windows, looking down at the market square, where wheezing cars the size of toes jutting out of his sandals pleased him. So easy to crush, he twiddled.

There was a king size jacuzzi next to a king size pouf bed opening into an oriental terrace garden with Japanese bonsai plants dotting latticed balustrades around little bridges under which a gurgling stream ran.

Over his head was a pergola covered in the greenest of vines. Wood wind chimes produced the sonic vibrations of a monastery.

The only thing missing here was a Steinway & Sons grand piano. Sami was ecstatic thinking how the moon would visit him once his fingers began galloping like a racehorse on the polished keys of a piano in this opulent house.

Adnan returned to the elevator, the Lift Kara De muzak (term for instrumental music in elevators) began throbbing in his veins like the tickle of a just-realised joke. He promptly wrote a cheque, sitting on the green seat inside which more and more looked like an emperor’s throne on his way down. It had translucent crystals on the head and gnarly claws for feet.

‘I will be buying seven more properties soon,’ he announced to the greedy builder.

Rumours spread again like immigrant hawkers. Elevators were expanded, muzak was changed, builders spread like snipers, shadowing Adnan to allow them to showcase their designs.

Prosperity increased Adnan’s size further. The elevator to his penthouse began to shrink in appearance. There were times when guests had to wait, take turns to reach because the elevator began to envelop itself around its prized owner Adnan and did not care to take another person in.

Other times, fed up with the Lift Kara De muzak, people began to avoid the elevator altogether. Adnan’s guests thought of his miserable health condition and began to abandon the space trip into his abode. Offers for music also began to dry up.

Epiphany was just around a corner, if there was any left in the elevator, waiting to explode. One evening, as Adnan was preparing to step into the elevator, he caught a reflection of himself in the mirror inside and watched himself trying assiduously to fit into the tiny compartment it had become.

The elevator gave in, the lights blacked out. Adnan was stuck, one foot in the elevator, one out, not able to budge an inch in or out.

The security guard in the lobby rescued him by yanking him out. Adnan wrenched out his green leather throne from the elevator, sat down and perspired, hating himself. The guard lit a candle and wrote a note on a scrap of paper, ‘Lift down’.

Adnan made a resolve right then. He grabbed the candle and in its flickering light, decided to walk his way up the blinding staircase to his penthouse. If the candle snuffed out before he reached his floor, he would use the staircase for the rest of his life.

At first he hopped stairs, then he huffed. Long after the wick had died in his scalded palm, he reached his door wet as a wave crashing shore.

Six years following his promise, he shed 100 kilos to become a new man.

Disbelieving producers welcomed him to merely ogle at him. A successful personal triumph rarely translated into work, often dissipating in mere gossip and speculation.

Adnan tried harder, but few were willing to give him new, excitable work. Curious as a lemur, all they wanted to know was how he had done it — the extreme weight loss.

Adnan happened to run into the builder in the parking lot. The builder had avoided meeting Adnan since the day of the fat cheque. He had fleeced the innocent musician with fittings and décor Adnan paid a double price for back then.

The builder, like everyone, could not believe it was the same Adnan he was shaking hands with. They chatted and moved into the lobby. The builder walked to the elevator to usher Adnan in first.

‘I will see you upstairs,’ Adnan said, moving towards the stairs. The builder, pleading, requested him to take the elevator as he was pressed for time and besides, he didn’t consider himself fit for walking fifty floors with Adnan.

Adnan relented and decided to accompany the builder in the elevator. Doors shut. Lift Kara De wafted.

The builder tried to humour him, ‘Aap ka purana ga-gaana,’ he stuttered. Adnan held court in a corner, urging the builder to sit on the concave leather chair whose crystals were dull of sheen and claws worn out with chipped nails.

The builder, as always, officious, sprung up when the elevator clinked for the fiftieth floor, ‘Koi problem hai toh boliye, kuch maintenance, koi change-wange karana ho toh kahiye.’

It was the best offer Adnan had heard all day. He smiled Buddha-like. It was time to change the elevator muzak.

https://medium.com/media/8d3b095ff1ec0b41402b85427e2cbc28/href