Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 7

November 21, 2019

Badnam Basti — India’s first film about gay love

Lost since 1971, found in 2019.

India’s first film about queer love — Badnam Basti, made in 1971, and lost since, has been found in an archive in Berlin.

What a story to remake/revisit perhaps, and give it its due in the canon.

In 2016, when I wrote this story for Scroll.in, “The untold story of ‘Badnam Basti’, possibly India’s first gay movie,” there was no hope of ever finding it.

I had read both the Hindi novel एक सड़क सत्तावन गलियां by Kamleshwar and its English translation A Street With 57 Lanes as part of the research and found the narrative of homosexual love bristling with unspoken emotions.

Badnam Basti could have set the precedent for queer love but got lost in transgression. It could have been a Brokeback Mountain because it did have an unnameable love story at the core of it.

Annie Proulx’s short story about two cowboys in Texas is set in 1963, but was written in 1997. Kamleshwar’s novel was written in 1957, way ahead of the Hollywood blockbuster that broke the dam.

Badnam Basti was also four years before a scene in Sholay (1975) in which Jai and Veeru are put in a prison cell with a colourful jailbird who struts around with lascivious intent. This standard played out for years and harmed more than helped.

Unfortunately, upon release, no one went to see Badnam Basti. Now the task of watching it, and bringing it to India is something worth trying for.

November 18, 2019

Poem: Standoff

The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya

The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goyain the play about disputed land

the owner aims an AK-47 at a usurper

a butterfly

flutters through the audience

and sits on the barrel of the gun

the actors remain calm and still

as a poem of Paash is invoked

मैं घास हूँ

मैं आपके हर किए-धरे पर उग आऊँगा

(i am grass

i will grow over all your deeds)

the butterfly hops

to the fake field of grass on stage

मैं तितली हूँ

मेरा कोई एक ठिकाना नहीं है

(i am a butterfly

i have not one resting place)

irony is not entirely lost

before it becomes evanescent

November 13, 2019

A poem in waiting

Christina’s World by Andrew Wyeth

Christina’s World by Andrew WyethEvery time the elevator ascends the floor

i can hear him coming through the closed apartment door

when he has in fact informed me on the phone

that he is on the way

i must have been waiting for an eternity

when all the sounds i hear are from his absence

October 27, 2019

true that Sukanya Basu Mallik soldier on.

true that Sukanya Basu Mallik soldier on.

October 26, 2019

Here is how I wrote my first book

Harper Collins India published it without my consent.

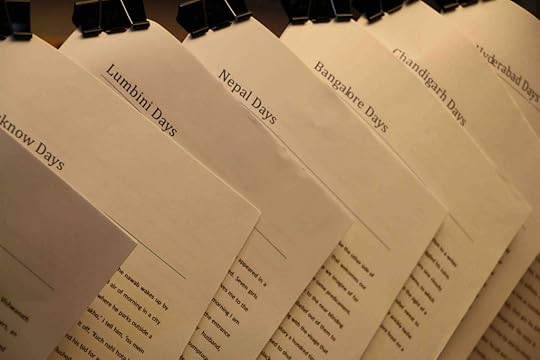

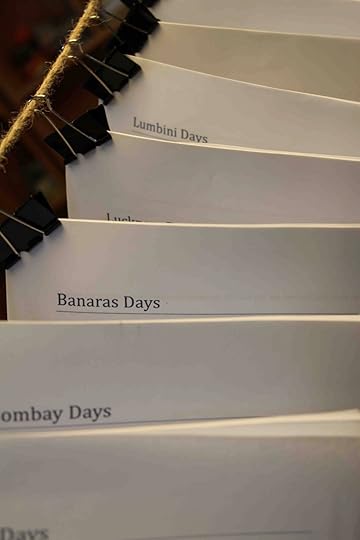

Chapter titles in Lean Days.

Chapter titles in Lean Days.In 2010, after reading how Elizabeth Gilbert wrote, and don’t judge me for saying this because I did not read the book — Eat, Pray, Love — only gathered information from her writing process that she took notes and kept a diary along her travels. No shit Sherlock, as they say.

I thought that is the done thing. Why was I not doing it?

I discovered Gilbert through the movie adaptation of her book. The movie was an endurance test. It was Julia Roberts eating pizza and ice-cream in the film that made me google Elizabeth Gilbert — someone I may or may not read in this life.

Fast forward to 2012, when I decided, enough is enough — how long must I go on like this — writing about food and music that came rather easily to me for a website called Buzzintown that was rather easier to write for.

No one read the website. I certainly did not. Ennui had set into my bones like granite — hard, heavy, and making me immobile.

On April 30, 2012, I decided I would not go to work from the next day: May 1 or Labour Day. It was my way of quitting.

So bourgeois!

On May 1, I flew to Madras. I went to my friend Namrata’s house and asked her to give me shelter for a few days. I told her I was going to write a book.

She fed me well. She did not disturb me when I slept in the afternoon (I seek the stillness of night to write). I felt free to write, understanding that I had finally managed to put myself in an idle state to wander.

Aimlessness is the compass we sometimes need in life to find a direction.

I traveled the country for almost a year, observing people and writing notes: Madras. Bangalore. Hyderabad. Delhi. Ajmer. Srinagar. Ladakh. Chandigarh. Manali. Lucknow. Kathmandu. Lumbini. Banaras. Calcutta. Bombay.

When I returned to Bombay, I had to press my restart button for the daily grind.

In January 2013, my friend Mohit gifted me a new laptop to write because mine was stolen in May 2011.

Robbery at house this morning. Laptop stolen. Mobile stolen. Lodged complaint with police, they registered misplacement case. They say it’s my carelessness. My carelessness- laptop was downloading The Diving Bell And The Butterfly. My carelessness- cell was placed on Bolano’s 2666 next to my face. My carelessness-thief did not slit my neck since there was no money. Landlord rues loss of ‘data.’ Pardon me, ‘poems’.

In four months from January 2013, the first draft of Lean Days was ready. I had to look for work right away. I had mortgaged my life insurance policy to take a loan to write. That money was swallowed up by Bombay house rent bills.

The first chapter I cracked in January was Ajmer Days. I had emailed it to my friend Kapil who was attending the Jaipur Literature Festival the same month. He did not read it but took a print out and submitted it to Mita Kapur.

Mita Kapur is the founder and CEO of Siyahi, India’s leading literary consultancy. She also conceptualises and produces literary festivals and events. Her first book, The F-Word, is a food book, memoir and travelogue. She has edited Chillies and Porridge: Writing Food, an anthology of essays on food. As a freelance journalist, she writes regularly for different newspapers and magazines on social and development issues along with travel, food and lifestyle. (sourced from siyahi website)

She read it and called me immediately.

Where is the rest of this? she asked.

I died but you must first understand why I died.

She is like the Anna Wintour of the publishing business. Her word is the word.

I wrote the entire book with the seriousness of a chipmunk eating an acorn. Do not make fun of their devotion to food. It is a religion: writing while chewing on an acorn.

The next year, I went to the Jaipur Literature Festival held in the Diggi Palace, with a full-bound manuscript of Lean Days.

Where should I meet you? I asked Kapur on the phone.

I am standing next to the swimming pool near the Durbar hall, she said.

How will I spot you? I asked.

I am wearing a pink saree. You cannot miss it, she said.

Indeed, there she was, regal, and terse as the pleats in her silk saree.

Send me a soft copy, she said, as I pulled out the manuscript from my tote bag.

She glided away.

Uh, I thought, all this way for a soft copy!

My friend Abhishek had sponsored my stay at the lit-fest. I felt bad for us both.

In March 2014, Kapur emailed me after reading it. She said:

Lean Days is part travelogue, part diary. The nameless protagonist travels across India in search of love and inspiration. Parts of his personality and past are gradually revealed as he travels.

This is the sort of book that blurs the line between fiction and non-fiction. The protagonist is a writer and the book is written as his travel diary — the reader is left wondering where the author ends and his creation begins.

The tone is very interesting. The protagonist is a poet and writer, and his diary reflects his more introspective, analytic side. Even his trysts with various men across the country are written in a gentle, yearning tone. It is not crass at any point. You can empathise with his search for love, as well as his search for himself.

What is also interesting is that it is a travelogue with a dimension that goes beyond travel. It isn’t simply a description of the places he visits and the people he meets. This is a relief as most travel books tend to be just about the journey.

My main problem with the book is its lack of structure. I understand that each of these chapters can be read as individual short stories, and that’s fine. It’s not the link between chapters that I am missing. The chapters themselves seem to be very loosely structured.

There is a tendency to ramble and also to pontificate. At some points, it almost seems like you’re forcing your erudition down the throats of the reader. The non-linear narrative is a little jarring at points, but not unpleasant.

The book could do with a lot of editing on your part. You need to sharpen the narrative, string together the stories better and keep the reader’s attention. This is not a ‘commercial’ book in any sense, so it isn’t pace or plot I’m concerned about. Right now, it reads as a diary. To make it a book, you might have to tighten your prose.

The end is abrupt. It is almost as if the notebook in which these reminiscences were written has run out of pages. Not satisfactory. There is a sense of him coming back to Bombay, but no sense of completion. If the author can rework and send the manuscript back, we’d love to give it one more read.

This was the first review. It was encouraging. I had to find an editor. I had no money in my pocket.

I emailed the manuscript to several other literary agents, asking them to fix the book and take a cut when the publisher picked it. I could not ask Kapur to fix it because I did not have the money, or the balls, to ask her.

I started emailing the commissioning editors in the Indian publishing houses in the hope that they would pick it up. No one showed interest but said it so politely.

In November 2015, when I had given up, a friend asked me to email the manuscript to Somak Ghoshal, the then commissioning editor at Harper Collins India (HCI).

I thought why not, give it a shot. I had never heard of him. I wrote to him and forgot about it.

In February 2016, Somak wrote an email to me. He said:

“I have read Lean Days and have enjoyed it a lot. You have a distinct voice and a finely stylised prose, both of which one doesn’t encounter often. I did like the idea of having city-based chapters and the structure of the narrative, based on the erotic yearnings. I wasn’t quite sure about a couple of early entries, especially the one on Varanasi which left me somewhat unsatisfied. Also, I am not a fan of the predictive future tense, the ‘I will do this and that’ manner of narration that you sometimes assume. These are, anyway, but editorial quibbles and we should be able to talk through these matters in more detail should we decide to publish this book. I am going to present your MS to my team next week and get back to you — hopefully with an offer.

Thank you, once again, for being so patient and showing me your MS.”

By this time I had collected several rejection notes with sweet words. This one showed a ray of hope.

In March 2016, Somak emailed again.

“I am delighted to offer you an advance of Rs XX,000 against standard royalties (10% HB; 7.5% PB; 25% e-books) to publish Lean Days with us. I was struck by your subject, as well as style, both of which are bold and fresh, though in the event of publishing this work, we hope you would be willing to revise and edit it according to our mutual satisfaction. Please let me know what you think. I look forward to hearing from you.”

That money was two months rent in Bombay.

Only house rent.

I accepted the offer immediately. Who wouldn’t? I could have gone somewhere else. But I was sure no one else would publish it. Somak had impeccable taste.

Bad news immediately followed the good one. Somak emailed me in June 2016, saying:

“I am writing to say that this is going to be my last month at HarperCollins India. I’m leaving you with Karthika, our publisher, who will be your point of contact. I’m sorry this comes in abruptly, but you’ll be in excellent hands at HCI.

One of the pleasures of working in publishing has been the encounter with new voices, and yours is one of those that have most excited me. As far as I can see, your MS needs fleshing out in some parts, and pruning a few, so nothing major. I’m leaving it with Karthika so that she can assign an editor to it. It’s going to be a really special book, and I’m confident it will be reviewed favourably when it’s out.”

This email made one thing clear to me. The book was going to be ruined.

Names were being mentioned — Karthika VK, Udayan Mitra, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, Ajitha GS — editors who were supposed to look into the book but who kept moving out and handing the responsibility to someone else.

It is said that if one editor commissions the book and does not look into its publication, the book suffers.

March 2017- Nothing happened. One year had gone by since the book was acquired by HCI.

April 2017 — Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri emailed saying he was going to slot the MS

May 2017 — Rukmini Chawla Kumar was going to look at edits, she left

July 2017 — Shantanu emailed saying he sent the MS to someone, didn’t mention who, wrote will send edits by Aug 15

Sept 1 2017 — I emailed, no response

September 13, 2017 — I wrote to Somak who had no business looking into this — he said he spoke to the CEO — Ananth Padmanabhan who said, “Do pass on my apologies to the author. Let me speak with Shantanu and take care of this right away.”

September 14, 2017 — Shantanu emailed me with the edit schedule, release date. That was quick!

At this point I have to mention how one lady called Ankita Poddar was assigned the edits. She had textbook rigour and a flair for unintentional comedy.

Here are a few examples of her edits:

1 — The narrator (of the book) writes about a woman laughing on a terrace across the road at night.

The sentence is: Her lady-like manners don’t seem to exist.

Poddar’s comments: This sentence is really sexist, what even are lady-like manners? Assuming there is such a thing, how do they not exist simply because she’s laughing loudly?

2 — The narrator writes about a dark-skinned carpenter he sees in the dark on the terrace.

The sentence is: His skin is too dark to register.

Poddar’s comments: His skin is too dark to see in the dark? I’m pretty sure that’s an extremely questionable statement.

3 — The narrator writes about the carpenter who jokes about his dark-skinned wife.

The sentence is: Black Humour?

Poddar’s comments: I can’t tell if the carpenter is actually black racially, or if this is racist humour.

Poddar edited the chapter for grammar and she did a fantastic job (although that is not how a narrator’s diary would read), but she weeded out the poetry, and the psychological framework of the narrator.

For instance, the carpenter in Lumbini Days is called lowly, primitive, and compared to a monkey asking for a banana in a towel scene (which she changed to a dog, because am guessing that’s aww cho chweet).

As for the rest of the edits, I took a glance. She had removed all literary references. Be it Manto, T E Lawrence, Sebald, or even the overdone Kafka, who I can still agree upon can go.

She wrote about the chunky one-sentence opening paragraph in Bangalore Days as making no sense at all.

For the Srinagar Days chapter she had written a side note, a part of which said, “Some parts, like about women and the male gaze, in a Muslim society are very sensitive topics. Also, there was a section that clearly separated Kashmiris and Indians. While the author wants me to keep some of the other controversial thoughts of the narrator in the text, I thought it best to delete something that has so clearly divided countries and spilt much blood.”

Who is this ultra-nationalist editor, I thought. She had removed entire pages in the chapter.

She said things like a sentence is promoting eve-teasing, another is propagating rape, that staring into other people’s book at Blossoms (a book store in Bangalore) in against the law (she’s not being funny), and a statement about a guy wearing a vest is classist, and one cannot pee into the Ganga in Banaras, and even that the narrator’s agnostic views should be curtailed.

As a queer man, it’s not okay for the narrator to make insensitive jokes about the LGBT community she said — how can the narrator want to be treated like a woman — its offensive to the community.

Hello clueless!

I had to write to Somak Ghoshal once again to intervene. Poor Somak, he wanted to stay away from HCI as far as possible. He was naturally shocked as I was.

Prema Govindan, commissioning editor at Harper Collins India was then assigned to look into it. She made one perfunctory telephone call to me, trying to run her edits by me on a phone call — imagine!

After 10-15 minutes she had to respond to something else, so she never called back ever again.

I emailed saying I can come to Delhi, sit with the team and quickly wrap this up — at my own expense.

No response.

I emailed if I should get another author’s blurb for the cover of the book. You know like when other writers praise a book without reading it and it appears on the cover to lure potential readers. Words like “mesmerising” or “elegiac” or “a new voice” are stencilled.

No response.

I emailed reference images for the cover art because the ones they optioned were not exactly wow.

No response.

I emailed saying the book could do with some images. (Why was I thinking I am John Berger?)

The response was “too late to commission any artwork”.

On February 13, Prema emailed from her gmail id (not official id) for the final edit.

On February 14, 2018, I had flu (or lack of a valentine date) but I tried editing the first three chapters and emailed it back saying I will need a day to look through the rest.

This is what Prema Govindan WhatsApped me on Feb 14…Valentine’s Day — it broke my already empty heart. (Thank god I archived her chats)

“We are long overdue on the press dates and considering that the changes you sent me till yesterday have been carried out with a few exceptions as per my discretion, I will consider the text as final from your side as well.”

Reading this, I did not respond. What was left to say? I could say no, but I was tired of the indifference.

My first book was going to the printers without my consent.When I received my complimentary copy in early March 2018, I noticed that she had removed her and Shantanu’s name from the Acknowledgements section thanking them for their inputs. When I emailed her asking her why she had done that, she wrote:

“Sorry I forgot to write to you about removing that, what with all the running around that was happening at the last minute. I had taken it out since we try not to include our names in books, unless, of course, our intervention has been major. I had meant to write to you but it completely slipped my mind.”

Slipped her mind till the first print was out? It sounded odd but I was beyond discussing it now. With whose consent did the book go to press then?

Who edited the book? Did it magically edit itself? Should I be happy and grateful that I was getting published?

Ironically, yes. Worthier writers languish. I lucked out I guess.

Lean Days was released in March-end 2018. The cover design was okay but the print was bad, the quality of paper used was the cheapest, the finish was awful.

I am not being an ingrate but truth holds its mirror crystal clear.

Prema assigned a girl Ronjini Bora to run the publicity campaign. She did nothing. She said they had no funds for a book launch event while all their other titles were being launched in fancy venues across the country.

She sent two or four dozen copies to Instagram book reviewers and that was it — and I had to email her that list and do the follow-up.

A friend tried to engage a Bollywood actor to launch the book (because she is the few who read), and maybe she was interested initially, but later decided to opt for her wedding instead. Well played.

The publisher did not put out copies in book stores anywhere except Bombay after I insisted for a few. The one copy they sent to the Oxford Book Shop in Calcutta was after a dozen email exchanges requesting them to.

No one had seen or heard of the book apart from the people on my Facebook friend list — and that too because I had been inundating their timelines like legit spam.

First Post, Arre, The Telegraph, The Logical Indian, Indian Women Blog, News 18, Rediff — they were interested not so much in the book, but my background — since this post I had written two months prior to my novel about growing up in a kotha had gone viral and the subsequent articles I wrote on Women’s Day, elaborating on it also got some views. To be fair, their interest might have generated sales of a few copies.

Indian Express, The Free Press Journal, Live Mint gave the book favourable reviews.

The Hindu, for which I freelanced and asked the editors to give it a look, was keener on reviewing an HCI book none of you have read — Koi Good News.

Scroll.in, where I had previously worked, would obviously not entertain my book because I had quit them without serving notice.

At this point I am tempted to say that readers have reviewed it independently on Amazon and Goodreads and have written to me privately (they still do) saying only good things about the book. It is very cute.

If I am to believe Somak Ghoshal and Mita Kapur, the book deserved better, not for me, for itself. Better print, design, marketing, promotion, and some chop-chop.

Now if only someone adapts it for a web series. I am told it has potential. I will not be writing it again.

October 14, 2019

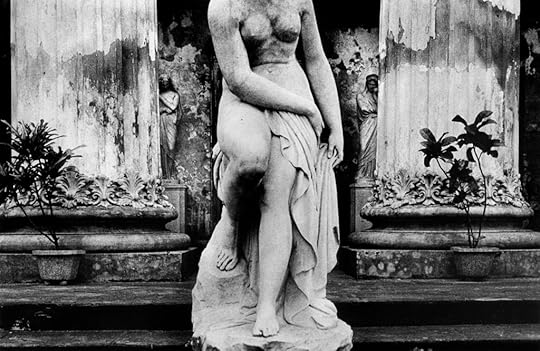

A Woman In Parts

A short story about impossible love.

Photograph: Raghu Rai.

Photograph: Raghu Rai.In 2010, a 35-year old married woman Shreya is arranging breakfast on a table in a house in Calcutta.

Her husband is reading the newspaper, sipping tea, and ready to leave for the office where he works as a banker. Her mother-in-law is switching channels on a television.

Shreya is distracted by the news of a 35-year old writer Asad who is in the city for the launch of his debut novel.

The news anchor is asking Asad, “Aapne iss kitaab ko Shreya ke naam dedicate kiya hai. Shreya naam ki toh bahut saari ladkiyaan hain, yeh bataiye, kya khasiyaat hai iss Shreya mein?”

(You have dedicated this book to a woman named Shreya. There must be many girls with that name, tell us, what is special about this Shreya?)

Asad: “Yeh har uss Shreya ke naam hai jo isse apni kahani samajh ke padhe. Waise Shreya naam sirf ek khayal hai mere zehen mein, haqeeqat nahi.”

(This is for all those women who can relate to the character Shreya as herself. Shreya is my imagination, not my reality.)

In the afternoon, putting her mother-in-law to bed for her siesta, Shreya dresses up in a tant saree in mustard yellow, a red tika on her forehead, and gold jewellery. She carries a blue umbrella in her tote bag, hails a taxi and heads out to the Oxford bookstore in Park street.

She watches from outside. Asad is signing copies. She steps in and picks a hardbound copy. She stands in queue to get it signed.

When Asad asks for her name, she says Sushmita.

He looks up at the striking lady as if he recognises her voice from his past.

Fifteen years ago, he used to talk to a woman on the landline.

He was 20. She was 20.

They never met.

They called it phone friendship.

Two lonely hearts in a chatty duet.

Shreya says, “Waise aap na bhi likhe toh chalega. Kahani mein kisi ka naam likhne se woh kahaani aapki nahi ho jati. Is kitaab par aapka naam hai, par shayad kahani kisi aur ki hai, mera naam likhne se yeh thodi der ke liye meri toh ho jayegi magar kal yeh kitaab, iski kahani, shayad meri na ho, kisi library mein padi ho, kisi aur ki dastaan suna rahi ho.”

(It’s fine even if you don’t write it. The story does not become yours if you give it a name. This book has your name, but it is a story of someone else, if you write my name in it, it will become mine briefly, but tomorrow it will languish in a library somewhere, waiting to be read as someone else’s.)

Asad nods. “Har kahani ki ek shelf life hoti hai, par har kahani ek khuli kitaab toh nahi reh sakti.”

(Every story has a shelf life, but every story cannot remain an open book.)

She says, “Kahani ko anth theek ussi tarah diya ja sakta hai jis tarah uska shuru hona mehez ek ittifaaq se hua ho.”

(Every story can be given an end exactly how it began as a coincidence.)

She collects the signed copy. Says thank you and walks away.

It starts raining outside. She walks to the door. She pulls out her umbrella and steps out.

He stops signing. He walks over to the door. Looks out. She has already taken a turn at the street turning.

He runs to that end hoping to catch her on the other side. He is getting wet in the rain. He can’t see her.

She has used a by lane to walk away.

She walks away, smiling, smiling the familiar smile that we know is her victory, putting this story to rest.

The umbrella in one hand, the other hand is clutching the book titled A Woman In Parts close to her heart.

She has ittifaaqan rumbled a new beginning for herself.

Photograph: Raghu Rai.

Photograph: Raghu Rai.

October 6, 2019

A Short Story About A Quickie

In and out.

Photograph: Prabuddha Dasgupta.

Photograph: Prabuddha Dasgupta.You’re like a flash, in and out, I said. The sex was like a comet.

A short, cascading whistle followed its cameo.

Isn’t that a story for you? What if I came and stayed? There’s no story there.

The character had spoken. I tumbled next to his naked body so that we could look at the small whirring white fan above us and talk.

Right now all I can hear from your words is the confusion in your head, whether to be on top or bottom, he laughed.

He was right. He was reading at jet speed, unlike the slow fan. How did he do it?

He had walked in as the clock struck twelve. No fairytale there. Lots of men in this city are awake for that hour to get laid after a few drinks.

He walks in and sniffs around the hall. I waddle behind him like a neglected duckling. He grabs me and kisses me on the mouth. He tastes like lust, viscous yellow, shiny and ephemeral.

Where do you want to do it, he asks, standing in the doorway of my flat mate’s room, who is away, holidaying in Kathmandu.

Whoa, easy, I go. Let’s sit down and talk?

Ya sure, that also, he plops himself on the sofa in the dim light of the hall.

He smells of alcohol and the sweat of other people sitting heavy on his conscience. A malodorous tongue has grazed behind his gold-studded ears, I gather, as he keeps touching it, as if to wipe off a cold, beery lick.

I met at least five people today, and none of them interested me, he says.

Oh so you’ve had sex with them?

No, not even one, somehow all of them have so much attitude. Some come with a list of expectations. They don’t know who I am! These television actors whose names I cannot take.

He’s from Delhi. I got that from the above statement.

He says he was a runner-up contestant in Mr India some years ago. Didn’t do much after it, slept with several actors, designers, including a toxic boyfriend who modelled for Versace.

I am super impressed. My knees are giving in. I am definitely not letting him go without a lick behind his ears.

Wine, would you like some, I move over to the kitchenette, to fetch a Jacob’s Creek, not mine. Flat mate will not flip. He asked me to finish it when he was going on a vacation.

Yes, why not, he takes a swig and announces how desperate he is to have me inside him. It is a good start. The wine goes inside him, and then I go inside him.

This hottie, with straight black hair, rugged good looks, perfect white teeth that glows in the dark, who is slightly out of his senses, twinkles his liquescent eyes, throwing his head back, sitting on the bar stool, watching me move around like an android totally hypnotised under his spell and ready to perform any action he would like; my master, my sage.

Doesn’t everyone look good in the dark, I wonder.

I can read auras, he tells me when I join him on the table. Auras vibrate in dark places. He is on to something.

You are a writer. I knew it when you opened the door and I saw your hands. And although I have not read anything, I know your writing is sweet. You believe in a love that is unaccomplished. You write about tragedies, but in a romantic voice. The only thing that is stopping you is yourself. You don’t care for money. You are waiting for that little fame that will establish you. It won’t come until you are confident. You need to show it. You need to go out and tell people who you are. Your writing is worthy of it. Your heart has been broken. You must not fall in love again. Not until 2016.

He is an undeniably good smooth talker. More wine is poured for him.

And I thought, who is this prankster, who, an hour ago sent me a message on Grindr, asking me to call him. There was no photo on his profile, just a picture of a naked torso. The torso was curiously tempting. We texted. I saw his face on Whatsapp.

I quickly rounded up my meeting with another chap who was sitting on the same sofa, same spot, sipping English tea and talking about the math classes he conducts for Cambridge students. Impressive, I thought, Cambridge, sitting here in Bombay. RIMS the school, where I teach, is affiliated, he said. I wasn’t paying attention. Rims, is where I stopped him and sent the chap home. Kids should not have to Rims! Ghastly.

You are a single child, with a single parent, you need to look me in the eye and talk, and that is why no one is taking you seriously, Mr India runner-up continued.

He then went on to give me a brief about his life. There were modelling days for designer names I cannot utter, he said. Actors he slept with, whose wives are looking the other way. He is on to his third marriage, he said.

I satisfy my wife, and no one in my family knows about me. It would not be accepted. A cousin in the army was pulled out when the family found out he was fucking a guy. He was tied and beaten up for a month, and I could not help. He is married today, forced, and living in London with his wife.

But that’s better, no? London, free, I said, complicit in the lust for a double life.

He smiles, and chooses to not comment.

Can you please draw the curtains; I want to take my clothes off.

I move to drape the windows, and turn to look. He is taking his clothes off like we are here for jacuzzi and wine. He sits on the bar stool, in the faint pool of one dim yellow bulb in the room. His body is toned, glossy, and he beckons me to come sit with him.

Shall I switch this light off, I ask, because hell, he is hot, and me, I undress with the lights out.

Am okay with anything, he extends an arm and kisses me.

He slides a hand inside me trousers to check how big I am. He is happy to know it’s a saluting member of the horny regiment. I am stroking his perfectly arched spine; I fumble for the right musical instrument — cello, viola, or perhaps an avocado.

I want to lie down here; he walks naked like he owns the space. I watch, and watch.

How can this drunken clairvoyant angel not intrigue me? He is so arrogantly sexy, strutting around like a showy bird; I could have tried my hand at sketching.

After sex, he kisses me on the forehead. This is where you like to be kissed, he says. Is he drunk, or am I dazed?

Don’t fall in love with me, he says. I nod approvingly, I must not. Quickies are a remedy for that.

We cooed, we sighed, we laughed in the middle of it. I said I’m not sure I want to have sex with you when I was in the middle of him. He said he knows I haven’t met a top to satisfy me in years. We laughed through that too, his anal muscles clenching in hoarse laughter, nearly bursting a vein in my penis.

That hurt, like love, absent in its predictably seductive and angelic form.

In the end, there was that all too familiar fairy tale trope.

I have to be home before it’s too late, he said.

And just like that, in a flash, the charlatan wrote himself into a story and disappeared into the fading blue night. Forever.

Photograph: Prabuddha Dasgupta

Photograph: Prabuddha Dasgupta

October 5, 2019

The Poetess

Chapter 2 & 3

2

Mukul sticks his tongue out; the tip touches his upper lip. He retracts it back, filling his mouth with a boom sound from the word lams. The word slips into his larynx, rising in his ears like an echo shaking a cave. He is practising not how to pronounce it, but how to use it in a couplet.

Lams, like lumps. Homonyms that rhyme are rumps and crumbs. But that’s icky, goes with cheese, he chuckles.

‘How did that Agha Shahid Ali get away with english ghazals?’ he speaks to himself. ‘The lengths some people will go,’ he murmurs.

He is running his fingers over the slim new titles in the poetry section at the Kitaabkhana bookstore in Fort. He smells them like nosegay. A new book of Mahjabeen’s poetry is out under the pseudonym Naaz.

‘Finally,’ he picks up the maroon cover, turns it over to check the yellow sticker that displays price, ‘too expensive.’ He does not bother to open it. He places it back and walks out of the store.

‘Books,’ he flares, ‘so unaffordable, ugh.’

His tall, wiry frame sticks out upright, his shoulders thrown back, he appears permanently confused with a tilt in his neck, that of a curious animal in a cage being offered a hand of kindness. It stuns him when he is told how lost he appears. ‘I am not,’ he has often dropped his shoulders to defend himself. And when everyone turns away, he’s back to his crooked posture. He has tried to watch himself. If he looks it, he has tried solacing himself, he probably is, with a shrug validating his tilt.

Mukul walks ahead in big strides, oblivious to a noisy world around him. He walks with a hauteur that possesses him. Wavy haired, long limbs, fair skin, lips not yet discoloured from his new-found fascination with lighting up, he has the features of a young boy even at thirty-five; the wonderment in his burnished bronze eyes catching in the mid afternoon sun glint like darting gold fish.

He’s going home, taking the slow local to Andheri, and following it with the metro to Versova. He came to town in the morning, to catch an Amrita Sher- Gil retrospective. The gate to the NGMA gallery was locked.

‘Sir, that show was over last week,’ the gatekeeper informed him. ‘Oh, I thought it was still running,’ he made small talk with the guard. Mukul had made a mental note with a wrong date. Mukul tried not to resent the guard doing his duty with a fake grin. He exchanged it with his own fake grin.

Picking a second-hand copy of Urdu ghazals, Mukul pampers himself. ‘How much?’ he asks the seller at a roadside bookstall. ‘One hundred,’ the bored vendor rattles. Mukul gets lucky. Now if only he can find a comfortable seat in the local to open it and escape into music.

Meena Kumari.

Meena Kumari.3

Nirmala was cleaning Mahjabeen’s room. She turned a few pages of Mahjabeen’s notebook, trying to decipher the Nastaliq script. She couldn’t understand a thing. It looked to her like a child’s attempt with ink on paper; funny wriggling lines with lots of dots in a triangle pattern she had seen tattooed on the chin and cheek of old Hindu women. Together with empty vials of lotions, medicines, powder boxes and perfume bottles, Nirmala decided to discard the notebook. That evening, when Mahjabeen’s friend Kalra came looking for it, Nirmala denied knowing that it even existed.

“How should I know sir, memsahib must have taken it with her in her grave?”

‘Shut up,’ Kalra reacted, ‘and look over there, in that cupboard, it must be here, somewhere. I need it. I know she left it for me, she meant to give it to me.’

‘But it didn’t look like she had written something in it, it was like a child has been given a pencil to scrawl on paper.’

‘How do you know, haan?’ Kalra grimaced.

Nirmala stammered, ‘Uhh, I saw her writing once, when she was sick, I thought she’s just scratching to pass time. I do that at the beach. I write words on the sands that have no meaning.’

‘Her nonsense is gold you fool, what do you know?’

‘Oh, then I should have saved it.’

‘What did you do with it?’

‘I threw it with the trash.’

Kalra collapsed on Mahjabeen’s bed. ‘Uff, what was that line…Agaz toh hota hai, anjam nahi hota…’

‘Jab meri kahani mein woh naam nahi hota,’ Nirmala seconded him with the following line of the sher. She stopped sweeping the floor, holding the broom’s thick end to her chin like a child amused at her own cleverness. She did not want the two names side by side. Kalra & Mahjabeen. Like how names were written on wedding cards.

‘Aaargh,’ he punched a fist in the mattress, ‘You bloody know everything, now I have to take poetry lessons from a stupid servant girl.’

Nirmala took that as her sign to leave. When people were discourteous, she grew aware that she belonged to a class that was born to suffer in silence. Her naiveté was no longer harmless, its display reaffirming to those who could hire her for her efficiency and yet not fire her because she lacked common sense. How could she know better? She was asked by the landlord to clear Mahjabeen’s room. That’s what she did. How was she to know a notebook contained gold nuggets for the future?

Her eyes did not tear up. Why should she cry? Kalra should cry. He’s the one looking upset as if he’s dead, lying on Mahjabeen’s bed, staring at the ceiling, contemplating god knows what. Suicide? Hope so, she thought.

Nirmala took the stairs down. She was not offended by Kalra. She smiled to herself, she felt superior to him. She knew Mahjabeen’s words, she did not have to look for them. They had become songs on her lips. She could hum them; she could bring them back to life whenever she desired to reminisce about the old lady. But she could do with a little help there. It wasn’t as if it came to her immediately. Someone would have to sing the first line, like Mahjabeen used to do, lying in bed, shuffling a pack of playing cards while Nirmala massaged her callused feet.

Mahjabeen used to joke, ‘Gently Nirmala, these feet have no ground beneath them.’

Nirmala recollected yet another line, ‘Har shaks ki kismat mein inam nahi hota.’ Nirmala laughed, evil, if it should appear, that Kalra was undeserving of the notebook.

Serves him right, she thought, to sprawl on Mahjabeen’s bed, grieving on her sickly sheets. Nirmala hadn’t heard of Kalra’s poetry, not that Mahjabeen ever mentioned it. He was one of those hooligans, who came to her, just like the rest of them, pretending to be her fan while downing glasses of free alcohol.

Suresh had once taken Nirmala to see a picture at Minerva theatre. When Nirmala saw her memsahib shaking those broad hips, she gasped, stunned that the surly woman could be convivial if given a penny for her thoughts.

‘I must tip the memsahib,’ she thought to herself, when some people tossed coins at the screen in merriment. She chuckled at her immodest suggestion.

October 1, 2019

The poetess seeking an audience

Chapter 1: Main Shayara Hoon

Meena Kumari.

Meena Kumari.If it had ever occurred to Mahjabeen that she would have to time-travel to be heard, she would have done it sooner than later. Sooner than later? What a vexing conundrum, she thought, assaulting a spittoon with a gob of chewed paan.

Mahjabeen was coughing her last phlegm, anticipating death to be closer than further ahead. Another vexation.

Nirmala, who was still intrigued by the strange translucent windsock lying on the floor mat, said, ‘Aapa, this jaraab, it’s not even your size.’

Mahjabeen tailed her malignant cough with laughter. ‘Pagli, blow it first. It’s the kafan I got from Mecca.’’

Nirmala’s eyes widened. She adjusted her dupatta over her head, sanctimonious at once, ‘I don’t have so much air in me.’

Mahjabeen grew irascible, ‘You’re full of gas, do it fast now.’

The girl sat upright on the mat, bunched the fabric and held the wide mouth of the windsock close to her lips and blew a short burst of air into its deflated glassy lung. The windsock lit up into a dull white light. Nirmala felt the windsock rising from her fingers.

‘This is flying,’ she cried.

‘Oh hurry up, hold it silly girl,’ Mahjabeen scolded her, ‘I don’t have much time, stop playing with it, it’s my burial bag.’

Three days later, staring at Mahjabeen aapa, who was stuffed in the sock, its mouth tied with a cherry red ribbon, the old woman looked like puffed, pale day-old pastry wrapped in a diaphanous cellophane shroud. Nirmala had seen something similar once at a confectionary store in Colaba. It looked expensive and stale.

The fresh ones were at the local halwai in Dadar where Nirmala went to buy curd and milk. The halwai let her pick the sticky, sugar crusted balushahi and press it between her thumb and forefinger. Oil rose up through its glistening brown folds, surging her greed, ‘Give me this one,’ she grinned at him, sinking her teeth into the sweet dough as she walked out with her day’s purchase.

Mahjabeen was laid in an enamelled coffin and lowered into the earth. Nirmala hoped Mahjabeen would melt inside the shiny bag and disappear as she had told Nirmala before she died.

‘I will not go into an afterlife. I defy faith. I will be back. In this life, in all of my wretched existence, no one paid attention to my fariyaad. I could not be a poetess. What then did I become, haan?’ Mahjabeen had ranted.

Nirmala had sat silently, listening to her tirade. Nirmala had found her very becoming of a maharani and had nicknamed her so.

Mahjabeen’s career as an actress was long over. She was bloating and gloating. She wished to start another, as a poet in the stature of Mir, Firaq and Ghalib. Everyone had laughed at her. Some were even frightened of her audacity.

They liked her talking in the talkies, her moony voice full of grief, but when she began with her poems outside the cinema hall, they loved her even more. They roared with applause and filled her glass with cheap whiskey. Men who roamed the streets at night came in droves, the regular rascals Mahjabeen had befriended one evening, shouting from the ivoried balcony as her pallu slipped, baring her ample bosom to an unsuspecting crowd, ‘Poochte ho toh sunoh kaise basar hoti hai?’

Someone had yelled back kaise and that’s how her new endeavour began. A bunch of hooligans, Nirmala thought, milling at Mahjabeen’s doorstep every night in search of angrezi daaru and chalu shayari.

Meena Kumari.

Meena Kumari.

September 27, 2019

The Chrysalis of Lata Mangeshkar

She emerged into her own in this song.

When a young, gamine Lata Mangeshkar first sang Kuch Dil Ne Kahaa, she complained of a strange case of butterflies escaping her mealy mouth. They swamped the entire recording room in a tropical flutter of colourful wings.

No one believed her.

After the song recording, she requested music-maestro Hemant Kumar into the room to prove her innocence but the butterflies disappeared before he could step into their world.

“It’s fine, Lata,” he nodded, “You’ve got the cadence right in the song, and your nuance is perfect, as if a butterfly has found the most mesmerising chandramallika to sip nectar from.”

And then to puzzle her, he sang a repeat line from the stanza, “Aisi bhi baatein hoti hain… Aisi bhi baatein hoti hain…”

She stood stunned, silent in her musical trance, not knowing what she had felt. Her head began droning the dying sound of “Kuch bhi nahi…” like a siren inside her whole body, an undertow that moved in and out within her.

She hurried home and drank a pitcher of water, honey-sweetened water. Were the butterflies sucking nectar out of her soul?

She went to bed in a grip of fear. She dreamt the scenery of the song — Sharmila Tagore’s nubile charm matched with her outrageous bouffant; talking to the honeysuckles on a hilltop garden. That bun, a storehouse of nectar!

Lata decided never to sing the song on stage — butterflies would manifest in let’s say, the Royal Albert Hall — not entirely grotesque but she dared not.

Thirty years later, she sang the song for Hemant da’s Shradhaanjali concert after much consternation.

As she trilled, she saw, the audience, over a thousand people, humming and swaying in a stadium. They turned into gleaming butterflies and rose up in the air.

She finally understood the effect of her rendition. She had spiritually elevated them.

That uneventful day in the recording room when she had sung it for the first time, the divine had entered her voice and freed her soul.

https://medium.com/media/c1addd75f00db9d55adcc81e68310134/href