Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 2

October 17, 2021

SRK, Is Your Silence Hindustani?

Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights. Speak up, your silence is hurting.

Sir, everyone should know by now that your mother was a social worker in contact with members of the Indian National Congress. Your father was a freedom fighter. Naturally, you can be expected to carry forward their beliefs and share the same ideology. Why shouldn’t you? But your deafening silence, that’s unlike your patriotic parents. Come to think of it, that’s unlike your own high-energy style too. Picture shown above is not for illustration purpose only.

The reason your son is in jail is not because he wanted to have a blast, but because you don’t walk the line that the establishment wants you to. What have you done to upset them? You’ve even endorsed those stinky national-pride gutka brands in godawful ads.

Your films have questionable merit but your character, oh no sir that is unimpeachable.

Your off-camera wit, charisma, and your dimples bolster half your everlasting appeal. Like in one of your better films, you have the nation’s women, children, and men eating chick pea out of your hands the way you fed pigeons with an assuring ‘aao aao aao’ feed call. You are an ingenious pied piper.

The establishment wants to employ precisely this imperishable skill of yours to herd us into an Orwellian nightmare. You must have politely declined to be a part of their evil schemes. You can distinguish between film and reality. They cannot.

Folks from the film industry are silently standing in your support. They are afraid to speak up because the attacks will begin with a tax raid. And it will be relentless bullying after that.

You have always kept a distance from politics. It has benefited you. But now they have come for you. Your family is being harassed. It will be your friends next. If you do not speak up now, you will forever silence your friends and supporters. When they are targeted, they will say you, king-like, didn’t say a word, why should they who are like feeble subjects before you? Who will stand for them? The film industry’s syncretic roots are being systematically dismantled to establish a new one nation, one religion order.

Speak up before your industry becomes a tool for political propaganda. We can see how a section of it has already become servile. Do not let them dictate how to make your films. Do not let them dictate how to lead your lives. They’ve already ruined radio, print, and television for generations to come. This country leads with the most Internet shutdowns in the world.

Your well-wishers will say do not speak up. Do not! You have everything to lose. Yes, you do, and no, you don’t. You have your father’s legacy, your mother’s spirit, and the gift to pass it on to your own children who are being tested.

Nobody doubts that you are a hero in reel and real life. Just say something. Don’t be quiet, even god tweets. Be human like us. Give us hope. Give us courage. Tell us you will not tolerate this nonsense. Tell us you will fight back. Don’t be mute. Tell us only two words if three will be too damaging (flag waving optional): Inquilab Zindabad.

August 30, 2021

Sahir Ludhianvi’s heartbreaking lyrics about his mother’s hardship

Tu mere saath rahega munne.

Sahir Ludhianvi with mother Sardar Begum.

Sahir Ludhianvi with mother Sardar Begum.Writer Khushwant Singh once wrote pithily about Sahir Ludhianvi’s gynophobia (fear or dislike of women) and gamophobia (fear of marriage), most likely linked to his mother-fixation, saying the poet-lyricist probably drank himself to impotency.

Sahir, though romantically linked with several women, loved no woman as much as he doted on his mother Sardar Begum. She had walked out on her notoriously bigamist husband Fazal Din and raised him alone, inspiring Sahir to write the rousing poetry of Tu Mere Saath Rahega Munne in Trishul (1978).

https://medium.com/media/49c4775421cffc697c772354af8d9a17/hrefThe poem had been marinating in his heart for a long time. It wasn’t until her death that he found the right words to express her feelings.

In the film, Waheeda Rehman walks out on her lover Sanjeev Kumar who marries another woman. Holding her infant, she sings the song, traipsing down a deserted road with tears in her eyes but courage in every stride forward. Her words are woeful but strong. She raises her son in harsh living conditions, and on her funeral pyre reminds him to avenge her tormentor, her husband.

It is a stirring melody, evocative, and perhaps even holds a candle in the wind to the troubled times Sahir’s mother faced when her husband harassed them for Sahir’s custody after she left him.

Tu mere saath rahega munne

Tu mere saath rahega munne

Taaqi tu jaan sakey

Tujhko parwaan chadhaane ke liye

Kitne sangeen maraahil se

Teri maa guzri

Tu mere saath rahega munne

***

You will stay with me son

You will stay with me son

So that you see

To raise you

What treacherous paths

I’ve had to tread

You will stay with me son

Composer Khayyam strings the melody with minimal fuss, using slow-tempo instruments in the background to focus on Lata Mangeshkar’s plaintive voice sung as an elegy at her own funeral. She begins the song haltingly, in sync with the distraught mother’s slow steps, and gradually, as the mother soldiers on through strife, her voice rises with formidable strength, echoing a war cry from her ashes. It has a heart-wrenching, cathartic effect.

The song is a powerful bridge that connects the mother-son bonding in film as in real life and death. Begum died in ’76. The song was released two years after her death in ’78. Two years after the awe-inspiring melody, Sahir too died in ’80.

I didn’t know of the existence of this fierce lullaby till a few days ago, when my mother who was watching it on a music channel turned to me half-smiling, half-foggy inside her square specs, she said, “Yeh gaana maine tab suna tha jab tu mere pet mein tha.”

Awkwardly, she laughed and said, “Roxy theatre mein dekhne gayi thi.”

I was sitting across her. I couldn’t look her in the eye. My tears started welling up. She too had walked away from my father, he a notorious bigamist, and they too had fought an ugly battle for my custody.

And to think she was watching this song on the big screen back then when I was a foetus, caressing her belly with the gentle words of the stanza: Tera koi bhi nahin mere siwa/Mera koi bhi nahin tere siwa/Tu mere saath rahega munne, almost pierces an arrow through my unborn state of mind.

The indignities a single mother has to face to raise a child alone. I cannot even imagine how tough it must be.

In one stanza, Sahir writes: Main tujhe reham ke saaye mein na palne doongi/Zindagaani ki kadi dhoop mein jalne doongi /Taaqi tap tap ke tu faulaad baney/ Maa ki aulaad baney/Maa ki aulaad baney /Tu mere saath rahega munne

Contrary to the iron gloves Sahir’s mother wore, my mother, impoverished greatly by her own unfavourable circumstances has always said: Bade naazo se paala hai tujhe maine/ Kisi baat ki kami nahi hone di hai.

Maybe that’s how I will write my mother’s swansong.

August 26, 2021

Why is a woman’s place at a man’s feet in Hindi film songs?

Sharm nahi aati hai iss liye aaj yeh poochna hoga…

There is a song in the film Padosan that goes, ‘Sharm aati hai magar aaj yeh kehna hoga/Ab hamey aap ke kadmo hi mein rehna hoga.’

It loosely translates as: I am bashful but I have to admit/ I am destined to reside at your feet.

‘This song needs to be updated,’ I said to my mother watching in on the telly.

‘Why?’ she asked.

‘Which woman in today’s time will want to live at a man’s feet? What is she, a daasi, an abla naari?’

‘Arre, in those days,’ mother said.

‘Those days are over.’

‘You won’t understand.’

‘I don’t want to. Love does not have to be servile. Where is the equality in this? The heroine (Saira Banu) is admiring the hero’s (Sunil Dutt) feet as if she is into fetish, which would be okay if she was kinky.’

Mother laughed.

https://medium.com/media/36070034347fe710d175520218665977/href‘Guess who wrote the song, a man, right?’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Rajendra Krishan,’ I googled.

‘He also wrote Tumhi meri mandir, tumhi meri pooja, tum hi devta ho (You are my temple, you are my worship, you are my lord).

In that song, the heroine (Nutan) touches the hero’s (Sunil Dutt again) feet and sings. What is with this lyricist making women sound so subservient to men?’

https://medium.com/media/869f8b671c81431328633b49374b88db/href‘As a poet, he should have chosen his words sensitively and been mindful of projecting women with equality, no?’

‘What should the song be?’

‘Just tweak one word. Say pehlu (side) instead of kadmo. Stand beside the man, barabari mein, why fall at his feet? When a man expresses his love at a woman’s feet, it is more about haseen paaon, alluding to her beauty, and submitting through it. Here the heroine isn’t singing a paean about the man’s slender feet, she is putting herself under it.’

Mother contemplated.

‘I think there should have been a three-level inquiry into the usage of that word. Obviously Lata Mangeshkar did not object to the word kadmo because she was used to singing about helpless women praying at the altar of the alpha male to rescue them. The writer (also Rajendra Krishan) and director (Jyoti Swaroop) must have explained some warped situation kadmo as steps, not feet, and gotten away. One can forgive the composer R D Burman for not questioning the lyricist because he did not want to interfere with the words (Gulzar’s poetry was already giving him stressful nights). But just look at how they filmed it.’

‘It is the situation,’ mother said.

‘What is the situation? The hero is injured. The heroine, who did not like him, has now come to nurse him, and is feeling that her rightful place is at his feet? Strangely, she is aware of her emotions, sharm aa rahi hai she admits, but what to do, a man’s feet is where her heaven is. Uff.’

And since then the song has been stuck in my head.

I hum: Sharm aati hai magar aaj yeh kehna hoga/ Ab hamey aap ke pehlu hi mein rehna hoga.

Lata effortlessly lifts and drops the last syllable of the second ‘ho-ga’ with such a delicate, light touch of wilful submission that it is impossible not to love this beautiful melody.

July 29, 2021

Zaalima, what’s swimming in my Coca Cola?

A brief history of Coca Cola in Bollywood and Lollywood.

For a brand name that needs no further universal recognition, Coca Cola can do without the name-calling.

In the recently aired Hindi film song Zaalima Coca Cola Pila De from the film Bhuj: The Pride of India, the brand’s name is used without compunction. Singer Shreya Ghoshal (on playback) implores a zaalima (oppressor) to feed her a Coca Cola. Both the zaalima and the coca cola bottle are missing in the music video featuring Nora Fatehi who gestures suggestively an unquenchable thirst consuming her.

The brand recall is high but where is the damn coca cola bottle when you need it?

https://medium.com/media/0f214fbb6ac1e489b002eb718b22b42a/hrefWhile Coca Cola would certainly not have a problem with its brand name being used, why hasn’t it supplied the film crew with a truck full of the fizzy drink to be featured in the video?

In 1986, when Pakistan’s premier playback singer Noor Jehan sang the original Zaalima Coca Cola Pila De in the Punjabi film Chan Te Surma, it was filmed as a mujra in a kotha where the tawaif is urging her patrons to fetch her a Coca Cola. The universally loved fizzy drink is prominently featured in the hands of her rapacious audience; goons who chug it like illegal vilayati sharaab.

https://medium.com/media/3f921e4f6309073f0ed92932e8d581f5/hrefContextually, alcohol was prohibited during the Zia-ul-Haq regime, when the President-General himself was drunk on the power of the “Islamisation” of Pakistan. So what else would a courtesan serve in her kotha, if not the illicit desire for a real drink? She sang Zaalima Coca Cola Pila De but was clearly alluding to a much stronger beverage.

Coca Cola would have been happy to supply bottles even when it was being mocked in the mujra. Coca Cola entered Pakistan in 1953, when Pakistani films were hardly a place to advertise; the industry was just beginning to take shape in a newly formed republic. At the height of the prohibition in the 1980s if Coca Cola could piggyback on a popular ‘item’ number, why resist?

Chan Te Surma catered to a massy audience, and ticked all the promotion and publicity Coca Cola could get out of the film’s core reach in the province. This was in-film advertising without a spend. In truer words, Coca-colonisation was spreading its tentacles without moving an inch.

Prior to Zaalima Coca Cola, a 1958 film Aakhri Dao featured a song Main Prem Ka Passenger, Tu Husn Ka Coca Cola, sung by as inimitable a chanteuse Iqbal Bano. The song is all but lost to modern listeners.

On this side of the border, the brand name had been invoked in a 1955 film title Miss Coca Cola. Raj Kapoor walks past its billboard in Shree 420 (1955). Kishore Kumar and Madhubala sip it in Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958). Sharmila Tagore picks it from a vending machine in An Evening In Paris (1967).

There’s also been an actor Kamal Raj Bhasin who changed his name to Coca Cola, named his son Pepsi and whose nephew, actor Tahir Raj Bhasin can confirm that the family has received no monetary gains from the brands.

Coca Cola has been in India since the 1950s. In 1977, Coca Cola exited India over demands by the newly formed Janata Party government to share its recipe with an Indian investor and sign the foreign exchange act. In 1993 Coca-Cola re-entered the market when new liberalisation policies were agreeable to the brand.

In 1999, filmmaker and in-film advertising visionary Subhash Ghai crudely legitimised brands by incorporating them into the film’s plot. Coca Cola, Hero Cycles and Pass-Pass, a mouth freshener have greatly benefited from his films Taal and Yaadein.

https://medium.com/media/a00b3a0610aeb20e5ac4fb3802984b28/hrefRumour has it that Ghai had filmed the Ishq Bina song sequence in Taal with both Pepsi and Coke bottles and shown it to both companies. The highest bidder got to promote the sentimental value of puppy romance through a ‘jootha’ or shared bottle of Coca Cola.

Jootha is a unique Indian food-sharing concept that has no English equivalent in language and practise. Through the soft-focus visuals, the song captures the hearts and minds of the emotional Indian people in the A R Rahman melody — Gur se meetha ishq ishq, imli se khatta ishq ishq, bottle uncapped and delicately sipped through a straw to release a frisson of everlasting thoughts. Coca Cola luckily remained unscathed despite the cringe factor.

In 2016, Coca Cola took the cringe out of the dated Zaalima tune and rehashed it in Pakistan. Singers Meesha Shafi and Umair Jaswal gave it a ‘millennial twist’ for Coke Studio 9, taking one of their own quirky, kitschy melodies and making it cool for the next generation. It was just a matter of time for Bollywood to appropriate it.

https://medium.com/media/e8e1a80bde60d39a6e64cbca5cb67a66/hrefMusic composer Tanishk Bagchi is a repeat offender, remixing classic songs and in this particular case, the brand. In 2019, he recreated singer-composer Tony Kakkar’s pop tune Coca Cola Tu in the film Luka Chhupi.

https://medium.com/media/22d1fade29a8568b140925378fcedfad/hrefWith Zaalima, Bagchi is at it again, but he gets it horribly mixed up. In his version, the chorus intro copies Ghagra (Yeh Jawani Hai Deewani). The lyrics, ‘Chandi jaisa rang hai mera, sone jaise baal’ is a direct lift from Qateel Shifai’s ghazal of the same name popularised by singer Pankaj Udhas. Add to it, the Bollywoodisation (or T-Serialisation) of a popular Pakistani melody, where Shreya Ghoshal is far too sweet to match Noor Jehan’s urgency in tone, pitch and rustic Punjabi accent. Three songs are murdered to create one butchered hack job.

The recreated Zaalima song is for a film based on the real events of the 1971 Indo-Pak war. The film’s makers have not taken into consideration that the Noor Jehan melody was made in 1986. Time (an anagram for item), in all likelihood, travels for an ‘item’ number that has no sell by date. Like Coke.

https://medium.com/media/20a7e322e7dc1233dec6a3de0b670786/href

July 5, 2021

Delhi Belly: Making The Shit Work

How the unforgettable shit scene was planned through and through.

After an early pack up, the film’s actors decided to hang out at their producer’s Pali Hill bungalow for a few drinks with their director and writer.

Director Abhinay Deo poured himself a Black Dog.

‘We’re shooting the shit scene tomorrow,’ he said.

Aamir Khan, playing chess on his ipad, turned. His face morphed into a quixotic expression, ‘Accha, what kind of shit are you using for close-up?’

‘Mild, regular, de-caf, do I have an option?’ Deo sipped from his glass.

Imran Khan bounced off the window sill, where he and his co-actors Vir Das and Kunal Roy Kapur were perched, holding bottles of Bud, looking like stool-pigeons positioned to take a hit.

‘You gotta be kidding dude, real shit?’ Imran chugged ferociously from his bottle.

Deo shook his head.

‘Whose shit is it?’ Vir asked.

‘Dog poop yaar,’ said Deo.

Kunal stood up and walked towards the kitchen, ‘But…but…but,’ he hopped, ‘make sure it looks authentic, my dog’s poop is like deep fried peanuts.’

He began filling a bowl with masala nuts.

‘Is it a Pom?’ Deo asked.

There was no sound from the kitchen. Kunal was stuffing his face.

‘Ya man, you can’t use that tiny shit, use like big dog, lab-shit, you know, thlop!’ Imran made a sound with his mouth, hand dropping like jelly on his knee.

Shenaz Treasurywala sank further in her sofa seat, saying, ‘Fuck all that, why can’t we just go get some deep shit from Sulabh shauchalaya yaa?’

‘And say what?’ This was a made-to-order format for Vir to crack ‘Knock knock…who’s there…shit collector…shit collector who…’ he summed up in one breath.

All eyes were fastened on him for the punch line, when Kunal walked in.

Vir crinkled his nose, ‘What’s that awful smell?’

‘Can’t someone volunteer?’ Kunal was out of line to ask. Everyone turned to him, horrified.

Kiran Rao poked Aamir in the ribs. He had fallen off the discussion back to his game.

‘We use ketchup for blood, right?’ she said.

Aamir sat up.

‘Then why not use curry for shit?’ she said.

‘She’s right,’ Aamir played along.

‘Curry from Kareem’s then?’ Poorna Jagannathan was famished with the shit talk around this place.

‘Look, the character is suspicious…this curry has to look runny,’ Aamir suggested.

Kunal had walked in the centre, blocking Aamir’s face from Vir’s.

‘Baaju hatt,’ Vir said, ‘can’t you see he’s talking, move your bloody gaand from the middle, what is it…gaand hai ya brahmaand!’

‘Aabe chootiye, don’t you know that curry has to run through my…’ Kunal flared, ‘do you wan’t to hear the sound of that?’

‘Guys, guys, guys’ Aamir interrupted, ‘concentrate karo yaar, so the curry should have reached that state of putrefaction to look both like curry and shit.’

‘Quite right maamu, let’s order dabba gosht from Lucky’s,’ Imran piped in.

The writer Akshat Verma, who had been sitting quiet agreed, ‘Yea, that will be fine, burnt pepper shit texture.’

Next day Vijay Raaz arrived for the shoot.

As his minion stoops over his shoulders, saying ‘Sir, ye toh tatti hai,’ Deo announced a cut.

Raaz sniffed at the fragrant goo, dipped his middle finger in the steaming pile and sucked it dry.

A collective gasp of ‘Eww’ rose up from the unit behind the lights.

Someone in the unit gushed, ‘Kya intense acting hai boss.’

‘Isme kya hai,’ Vijay spoke confidently, ‘Mira Nair ki film yaad hai…usme humko genda phool khaana pada tha…merrigold.’

‘Saale bhanwre humko chaman samajh baithe…bhinn…bhinn…bhinn (he swirled his head to motion the flight of bees)…phool khaate khaate acting style bhi lotus-eating wala ho gaya…ekdum thanda thanda cool mijaaz.’

Poorna chuckled, ‘It’s ok, our director saab is not a tyrant, he will not make you eat shit.’

‘Kya farak padhta hai Madam, aaj kal ki filmon ke liye bahut kuch karna padhta hai.’

He picked up a piece of boneless mutton glistening in the gravy, plopped it in his mouth, ‘If not this shit, some other shit,’ he loped off with a desultory grin.

Most people present on the sets looked away in disgust.

Some excused themselves.

Bellies had begun churning.

https://medium.com/media/42bbc6388d74ce6dd8818cf634514e84/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

April 4, 2021

Nazia Hassan: ‘I am not interested in singing, it is just a hobby.’

How she met Feroz Khan, had a spat, and sang Aap Jaisa Koi in Qurbani.

It was an unremarkable afternoon in a suburb in London, as unremarkable as two hot-shot Hindi film celebrities Zeenat Aman and Feroz Khan relaxing in the house of a wealthy Pakistani businessman, who hosted them without fanfare.

‘Who is that?’ Feroz spotted a young girl in the garden. She was dressed in cotton overalls, wore two pigtails, and was engrossed in reading a book.

‘That’s our daughter,’ said the host, ‘Nazia beti, zara idhar aana.’

Nazia clumsily sauntered into the living room. She flashed a customary smile she had mastered for her father’s high-profile guests. Feroz noticed her lack of enthusiasm in her posture.

‘She sings very well,’ her father said. ‘You should ask her to sing in your film.’

Feroz smiled toothily and said, ‘I don’t make films for children.’

His arrogant style naturally deepened the silence in the room to a chill. Zeenat cut through his quip.

‘Ask her about it,’ she said.

‘Do you like singing?’ he asked Nazia out of courtesy to his host, the Hassan family.

‘Yes, sometimes.’

‘Would you like to sing in my film?’

‘I am not interested in singing as a career. It is my hobby,’ she shrugged.

Feroz straightened his back.

‘That’s good,’ he said, ‘Making films is my hobby too.’

Nazia smiled the standard I-hear-you smile with a 5-degree anti-clockwise head tilt. She wanted to return to her book.

‘Who is your favourite singer,’ Zeenat asked Nazia.

‘Barbara Streisand,’ she said, ‘I like women with powerful voices.’

‘Which song?’ Zeenat tried to coax a song out.

Nazia hummed the melody of Evergreen from A Star Is Born.

https://medium.com/media/4baba9c88d53f56974d54058ceb3ac68/hrefFeroz was impressed by her words and her choice of a full-throated stage singer not from Punjab or a Bombay recording studio. She had good, eclectic taste, like him, he thought, classy and international. Nazia exuded a laconic aura quite different from the eager to please classically trained kids in film music.

‘Why don’t you come to our studio? My friend Biddu could compose a song and we’ll see,’ he tried to make up for the politeness of the Hassan family over dinner.

‘Okay,’ she said, shrugging her shoulder nonchalantly. Feroz liked her casual vibe. He noticed the book she was reading, Sophie’s Choice. He feared asking her about it would unmask his own lack of reading skills. Well-read women were a great and attractive foil to his own brute intelligence.

Over the Christmas holidays, Nazia and her younger brother Zoheb frequented a studio.

Biddu initially asked Nazia to sing a Hindi version of Boney M’s Rasputin.

https://medium.com/media/3b76dfc6328df97136811ca072a9ad59/href‘I won’t sing this,’ she said.

‘Why?’ Biddu asked. ‘Feroz wants to use this in Qurbani, his new film.’

‘But this is not even original,’ she said, ‘People will laugh at me.’

‘Zoheb and I write our own songs.’

When Feroz heard of her refusal, he was pissed at her gall. He was giving her a break.

‘Look, I don’t give a damn about what you do at home with your fancy guitar your rahees (rich) baap got for you. This is my studio, and you will sing what I say. Ok? I am the producer and am your baap here.’

‘Sir,’ she calmly said, ‘Yeh original nahi hai, aur baap bhi ek hi hota hai na sab ka? (pointing an index finger up) original.’

A moment’s silence was interrupted by a loud laugh. Feroz was happy to have met his match. Nazia’s sweet face held firm ideas unpredictable from her elegant demeanour. She was going to have it her way or she would walk out without a hint of regret.

A new song was recorded in one take. Feroz liked her thin voice but it had a nasal quality that could do with a double track to give it an echo over the umtempo beats. The finish was spectacular but Feroz preferred Laila O Laila on the soundtrack.

https://medium.com/media/76028cabd0f13650d0c7e0767b0d64d1/href‘You were very good,’ he told Nazia, ‘but I think the other song will be a bigger hit.’

It was an old tactic to control a rising talent, pitting one against another, this time Kanchan, another relatively new singer. Feroz had a reputation to live up to as a ladies’ man.

‘Um hum,’ she nodded her head and confidently said, ‘Feroz ji, aap dekhna, yeh gaana saal ka sab se bada hit hoga.’

She teased him as she left the studio, parodying the lyrics and singing aloud, ‘Aap jaisa koi meri zindagi mein aaye toh baap bann jaaye, ahaa baap bann jaaye!’

Her innocent giggle tickled his conscience. Feroz Khan’s sugar-daddy charm had zero effect on her.

https://medium.com/media/595587727dbb568ebc48c1f0bb0e0940/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

March 25, 2021

Pooja Bhatt’s Relevance Is A Bitch

And she shows how to live life like a runaway bride.

In the opening scene of Pooja Bhatt’s film debut Dil Hai Ke Manta Nahin (1991), Anupam Kher, who plays her father (also her Daddy in her ’89 television debut) says, ‘For your naughtiness I will eat a papad and you will get a jhapad.’ A flustered Pooja runs on the deck of her father’s ship, and jumps into the sea.

Her grand entry into cinema is through the exit door.

She leaves even before she can be rightfully established. This trope of leaving abruptly has defined her career throughout.

She recently returned in Bombay Begums (2021) after a twenty-year gap saying, ‘Relevance is a bitch’ in a recent Film Companion interview.

https://medium.com/media/ab5e32bfd6af5ad74e8912eafd2cc2d3/hrefIn between she has worked as a producer, director, production designer and art director but it is her work as an actor that she is mostly regarded for.

She runs away a lot in her films.

It is telling on her part. She chooses them perhaps because it reminds her how she does not fit in conventional roles and it is best to touch and go.

In Sadak (1991), she runs away from a brothel with her lover Sanju baba.

In Saatwan Aasman (1992), she runs away from home with her boyfriend Vivek Mushran to live a full life. In their second film Prem Deewane (1992) they repeat the exercise as silly lovebirds.

In Junoon (1992), she has to run away from her husband Rahul Roy who could eat her up, and not in the most appetising manner. In Jaanam (1992) she cuts herself to save the same beastly Roy chap, but now to take him as her wounded husband. Bhatt and Roy also appear in the tv film Phir Teri Kahani Yaad Aayee (1993), where she is more often running into his arms.

In Sir (1993), her teacher Naseeruddin Shah encourages her to run away from her gangster father at the airport, imploring, ‘Bhaago, bhaago Pooja.’

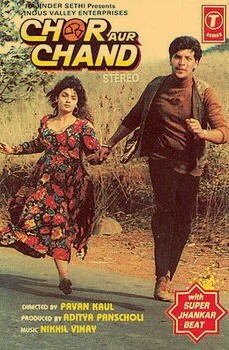

Chor Aur Chand (1993) spells out her running feat in the poster.

In Pehla Nasha (1993), a struggling actor Deepak Tijori helps her run away from goons chasing to kill her. Their hands are glued due to an accident involving superglue. The film briefly brings SRK, Aamir and Saif together.

https://medium.com/media/85392a5b2ff8124a5cd491089eb6c806/href

https://medium.com/media/85392a5b2ff8124a5cd491089eb6c806/hrefTadipaar (1993), as the name suggests, is about outlaws, and she is yet again on the run.

Kranti Shetra (1994) , a battleground for a revolution is a maze of a film where she gets lost.

In Naaraaz (1994), she desperately needs to escape the whiplash of her stepmom Soni Razdan.

By the time she did Gunehgar (1995), Mithun was the co-star she needed to get away from if she still desired a career.

In Hum Dono (1995), her dad won’t let her marry her ‘mamooli mechanic’ boyfriend Rishi Kapoor. She uses the great Indian rope trick, leaves home, gets into a jeep and ‘kidnaps’ him to sing and dance in some remote scenic landscape.

Sunny paaji rescues her from her kidnappers in Angrakshak (1995). But before that, since this is a Southern director’s masterful high-voltage drama, there are choreographed dance sequences where her running quota is fulfilled.

In her Tamil film Kalloori Vaasal (1996), a misunderstanding makes her run away from a friend Prasanth.

In Chahat (1996), she asks SRK if she should leave the mandap where she is set to wed another man, and run away with him. Later SRK’s obsessive lover Ramya Krishnan kidnaps Pooja and she has to eventually run away with SRK who saves her.

In Tamanna (1997) she has to run away from her crooked father with some incriminating evidence. He wants her dead.

In Border (1997) she will have to run towards the body of her dead lover whose news is on the way.

In Kabhi Na Kabhi (1998), the trauma of deciding between two lovers is tearing her apart.

With Bharat Kumar, there has to be some running around in Angaaray (1998). But Pooja must have got tired of it by now and began to wrap up her acting career with a wound Zakhm (1998) where she runs to the door to see if gali mein aaj chand nikla.

Yeh Hai Ashiqui Meri (1998) and Sanam Teri Kasam (also titled Sambandh and Yeh Pyar Hi Toh Hai) are the two films she would like to run out of her memory.

Everybody Says I’m Fine (2001) was her first English-language film, presumably also a language she is more comfortable speaking, and so she didn’t have to run away from this part.

And that’s when she stopped running because the roles she would have liked never came her way.

Her character is called Pooja in at least 12 films. Is that because her personality overshadows them? Probably. And so they don’t see her beyond Pooja and offer her versatile roles? It is one of the perils of being Pooja Bhatt, the persona who didn’t quite fit in despite her giving it a decade-long shot.

In the last scene of Dil Hai Ki Maanta Nahin, her concerned father advises her to run away from the wedding mandap. For a minute she does not heed him and walks up to stand beside her shady beau.

She then listens to her own heart.

It sings in Anuradha Paudwal’s sweet voice: Yeh beqarari kyon ho rahi hai yeh jaanta hi nahi.

https://medium.com/media/402d63dd2ff49993c717276f64b6b35b/hrefShe snaps her dupatta from his stole, and runs away, shaping a legacy for herself as the original and only true ‘bhagodi’ who made a career of running away.

Bravo!

Her performance in Bombay Begums remains opaque till a crucial scene where she breaks down, her lips quivering as she narrates her abuse. It is her finest moment in years. She is in a hurry in one previous scene to meet her paramour but she doesn’t rush through it. She’s still running, but she’s here to stay, as relevant as she was when she started too young to know better.

March 22, 2021

A Meeting Of Two Courtesans

Umrao Jaan and Vasantsena are soul sisters.

Draped from head to toe in gold, she walked like a beam of sunlight looking for a spot to radiate dust motes in the dark. She entered a van, startling another lady inside.

Sorry, I am, she had just begun to introduce herself.

Lilah, the other lady stood up and said, you are wearing more gold than I was sold for.

You are? the bejewelled lady asked.

Umrao, she answered. Umrao Jaan. She intoned like James Bond.

I am Vasantsena, the golden lady responded. I have earned this gold for what I am worth.

I don’t doubt that, said Umrao. You are exceptionally beautiful and alluring.

So are you, polite to a fault. Come, I want to show you more.

Vasantsena held Umrao’s hand and guided her outside the van, singing Mann kyon behka re behka aadhi raat ko.

Umrao laughed and answered, Bela mehka re mehka aadhi raat ko.

https://medium.com/media/4900025aaad88a585c4f4d4cbd966335/hrefKis ne bansi bajayi aadhi raat ko, Umrao asked, reacting to the sounds of a flute wafting from a thicket, like it was a musical sign for clandestine lovers.

Vasantsena chuckled and made it about a shy Umrao, singing to her, Jis ne palkein churayi aadhi raat ko.

They strolled past ancient neem and peepal trees, and entered a settlement.

Yeh kya jageh hai doston, Umrao cooed, wondering where Vasantsena was taking her.

https://medium.com/media/61c679734dde890c6e188b0c634d08d4/hrefYeh woh jagah hai jahan rishi Vatsayana ne Kamasutra likhi thi.

Vasantsena described the courtyard of the vaishyalaya where the two women were standing.

Oh, so this is not Faizabad, Umrao bit her tongue, then I am a perfect fit for this place.

No, no, you don’t say. I have brought you here to entertain us with you Lilah poetry. We do the rest of the work quite smoothly.

Umrao’s lips puckered in self-pity as the other not so modestly dressed girls giggled.

The scantily clad women of the vaishyalaya made her sing and dance all evening and then took the best-looking men into their bedrooms. They moaned and laughed aloud.

Justuju jiski thi usko toh na paaya humne, Umrao sang morosely in mehfils, iss bahane se magar dekh li duniya humne.

https://medium.com/media/57b48f10a696c57529b3015417ba5e75/hrefNo one understood the delicacy of her Urdu words or feelings. They clapped and hooted like unsophisticated people.

Not even a single wah.

The lascivious girls of the vaishyalaya spent all day gossiping about men’s swollen egos and tiny-bit merits, and toiled all night massaging them. Umrao felt left out, partly due to her own tehzeeb. She also wanted what they were having.

Umrao had to do something. She peeped into rooms and watched the twisted kama asanas, muttering Dil cheez kya hai aap meri jaan lijiye, bas ek baar mera kaha maan lijiye.

https://medium.com/media/fc21e0c16eb407d2bbd9ef92180fd5d5/hrefVasantsena said if you want to be like us then you will have to adopt our style.

Umrao readily agreed and began behaving churlishly, talking loudly to men and eschewing poetry and paan for crass behaviour.

Vasantsena personally trained her in the complex asanas.

In a month Umrao’s transformation from a soft-spoken poetess to a chatty harlot stunned everyone.

It was always in my ripped genes you see, Umrao said, defending her new lifestyle. In ankhon mein pehle se hi masti thi.

https://medium.com/media/e341229c0d4a7b84aa0e9a1e53a21e2c/hrefImpressed, Vasantsena let her be, but worried, she asked, who will teach us coquetry now?

Just then, Charudutt, a client of Vasantsena, playing a flute, sang Sanjh dhale gagan taley hum kitne ekaki, as he crossed the vaishyalaya at sunset.

Chhodh chale nainon ko kirno ke paakhi.

https://medium.com/media/2302cec5137da89db2d96da5f6729c03/hrefUmrao remembered the flute when she first met Vasantsena. It was his musical call for her. Both Vasantsena and Umrao rushed to get a glimpse of the man, his melodious voice mirrored their sadness.

Umrao responded, Jab bhi milti hai mujhe ajnabi lagti kyon hai, zindagi roz naye rang badalti kyon hai.

https://medium.com/media/3753c26cf46dcfecf0a6e2936bcbd8f2/hrefHer impromptu shayari elicited a wah from Vasantsena. It surprised Umrao. She missed the applause. Nothing else was worth living for here.

Umrao realised she wanted a life of singing and dancing and music. Charudutt’s voice had stirred those suppressed feelings. She missed poetry. She rushed out, sat in Charudutt’s cart and left the vaishyalaya.

When they reached another village, Charudutt worried how he, a poor man, would fend for their lives.

You don’t have to worry about that, said Umrao, as they entered his house. She dropped the black shawl she was wrapped in. Underneath it, she was studded in gold.

Will you lend me a hand to unhook these? she teasingly said to a shocked Charudutt.

I will show you a great asana in return, she cooed.

He dropped his flute and reached out for her humming neck.

https://medium.com/media/1562d953ef7e21a6053190dc6de515a7/href

March 17, 2021

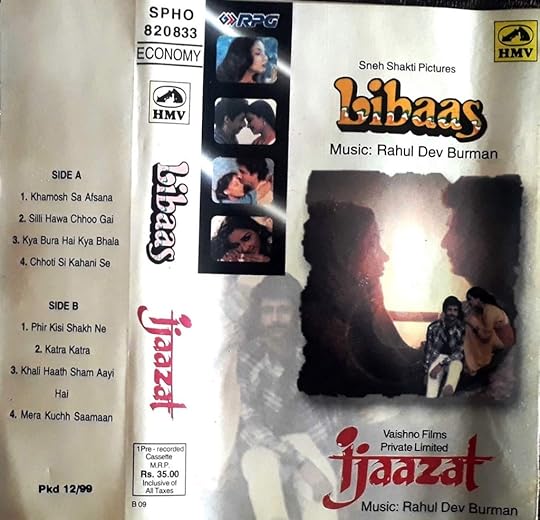

The Identical Songs of Ijaazat and Libaas

Is Asha’s ‘Mera Kuch Samaan’ better than Lata’s ‘Sili Hawa Choo Gayi’?

Asha begins singing Mera Kuch Samaan with a rounded ‘a a a a’ alaap. Midway through Sili Hawa Choo Gayi, Lata catches the throaty alaap and responds with a feathery ‘o o a a’ as if the two sisters are communicating a mnemonic melody code that glues their sisterhood.

It is incontestable. They are incomparable. The two slow wave tunes segue to reach for a common shore. The sisters sing inseparably from each other’s grief of estrangement.

The four songs sung by Lata in Libaas (1988) sound like a rejoinder to the four songs sung by Asha in Ijaazat (1987).

Sample this: In Mera Kuch Samaan, the words are

Geela mann shayad bistar ke paas pada ho

Woh bhijwa do, mera woh samaan lauta do

***

My liquid thoughts are lying beside the bed

Send them back, return those possessions of mine

And in Sili Hawa Choo Gayi they are

Jitne bhi tay karte gaye badhte gaye ye faasle

Milo se din chhod aaye saalo se raat leke chale

***

No matter how much I measure the distance grows wider

I have left day by miles and with night I have walked eons

The two songs are having a conversation, a medley, an antakshari. They meet at a crossroad, where intangible possessions are bartered for tangible memories.

https://medium.com/media/14eb561f9a9255679ef4a426e7eaecaa/hrefThe ‘geela mann’ rosebud in Mera Kuch Samaan blooms into a ‘geela sa chand khil gaya’ in Sili Hawa Choo Gayi. The once-in-a-full-bloom ‘chand’ of Sili Hawa Choo Gayi sashays by a hundred and sixteen times, ‘Ek sau solah chand ki raatein,’ in Mera Kuch Samaan.

https://medium.com/media/89345e2ea8d1f268754e738deb50a56a/hrefStudded with mixed metaphors, these songs of separation and longing are united in the abstract expressions of love. Rarely does a lyricist write words with such emotive feelings of interiority through the usage of synaesthesia.

Lyricist Gulzar’s poetry sounds as ephemeral as it is everlasting. Combined with composer RD Burman’s simple and yet intricate music harking on familiar background sounds of the five elements of nature; the faint breath of life itself pulsing in the atmosphere gives these tunes a longer shelf life than the commercial sounds he produced on demand for hit tracks. These tunes are not rushed. Just check how the two tracks end in whispers. Asha slows down hushing ‘Main bhi kahin so jaungi…’ Lata trails off into a mist singing ‘la la la la’, doing a mysterious disappearing act. These tunes linger thereafter, like a shadowy figure in one’s dreaming head.

In the mid-Eighties, Burman stopped churning because Bappi Lahiri was overdoing it. Burman entered possibly his philosophical stage in music — just to be precise: spiritually divine, not devotional. It had to have purpose and meaning. It was time to stop ratcheting hit tunes using the ‘same old-same old’ popular words and phrases circling dil, jaan, pyaar and jigar.

Another aspect to consider is Gulzar slowing his pace. Burman found himself grappling with Gulzar’s unmusical poems that sometimes read like a newspaper’s headline, he once quipped. Burman’s music found new expression, unfollowing rules and inventing new ways to accommodate words that were often not set in rhythmic metre because Gulzar wrote in blank verse that sounded like mundane prose.

Gulzar is a first-rate poet and in his own modest opinion not as good a lyricist as his longest-lasting contemporary, the very prolific Anand Bakshi.

Gulzar is right.

How many of Gulzar’s lyrics can you sing beginning to end without encountering and stumbling over an unfamiliar Urdu word or a complex metaphor that takes time to swallow? ‘Main chand nigal gayi daiyya re ang pe aise chaale pade!’ I swallowed the moon, my body writhes with blisters! It is in metre but it is saying the unthinkable, perhaps even traditionally, the unwholesome. ‘Jab hum jawaan honge, jaane kahan honge.’ That fits, syllable for syllable. Simple, sweet, instantly relatable. Bakshi writes this for Burman.

Lyrics dilute poetry, aiding music to reach en masse. Though that is not always the case, as Gulzar’s poetry stands distinctly apart for this very reason, trying to blend the two successfully and for which a melodist like Burman, trained in the classical raags and modern jazz-pop instruments, fuses magic.

https://medium.com/media/10576d8fa3a4c4896297755e3dbcf2bb/hrefLata’s trailing ‘la la la la’ reappears in Khamosh Sa Afsana, where the themes of love, legacy and mortality seep into Asha’s Khaali Haath Shaam. The Mangeshkar sisters speak to each other through smoke and mirrors.

Khamosh sa afsaana paani se likha hota

Na tum ne kaha hota na hum ne suna hota

***

Had this lore been written in water’s invisible ink

What you had not said what I would have not heard

************

Khaali haath shaam aayi hai khaali haath jayegi

Aaj bhi na aaya koi khaali laut jaayegi

***

Empty-handed evening has come, it will go back empty

No one has come today too, the evening will return empty

The former is about composing a fable in invisible ink and the latter arrives empty handed to document the missing.

Asha’s immeasurable ‘Katra Katra Milti Hai Katra Katra Jeene Do’ could only be collected in the ample shade of Lata’s ‘Phir Kisi Shaakh Ne Phenki Chaaon Phir Kisi Shaakh Ne Haath Hilaya.’

Interestingly, a line ‘Pathjhad ki woh shaakh abhi tak kaanp rahi hai, woh shaakh gira do, mera woh samaan lauta do’ in Mera Kuch Samaan, a message is encoded for Lata’s chipko-huggable deciduous, hand waving tree branch.

Asha’s Choti Si Kahani Se cuts the upbeat but standard tabla-baaja sounds of Lata’s Kya Bura Hai Kya Bhala short by appearing to be slightly less shrill with its use of the piano-accordion, strings and madal. Bura meets its choti si pair of scissors. Asha softens the end with the ‘la la la’ of La-ta.

https://medium.com/media/a8cee762998aa2dd787bd9ac1e2f033f/hrefThe two films were made around the same time but only Ijaazat got a formal release. Libaas was never released. The producer could not agree with the lyricist-director Gulzar on the open-ended climax of the adultery drama Libaas, which was one of the reasons why Gulzar made the other adultery drama Ijaazat. He did not have to obtain permission from an interfering producer to interpret the story the way he wanted.

Asha and Lata were given identical songs, the tunes of which were also similar. Lata had won a National Award as Best Female Playback Singer for Beete Na Bitai Raina (Parichay), lyrics by Gulzar, music by Burman. He had to prove Asha as equally deserving. She got it for Mera Kuch Samaan. That must have been such a triumph for Burman and Gulzar.

https://medium.com/media/59ef1b63ab91cb75c055e38a6d615b9b/hrefThe Asha-Lata feud, if at all, is professional. What makes it even wilder to imagine is that it feels almost as if RD Burman and Gulzar are conspiratorially chiselling a wedge between the two singing sisters to extract their best. The ruse works fantastically in these two soundtracks that compliment the two sisters like no other collaboration in film music. Ijaazat vs Libaas is their most beautiful and ultimate musical album face/off.

Lata mandir ki aawaz hai

Asha maikhane ki

Dono mein utni hi parastish hai

Jitni ki dono mein pyaas

Lata woh sunehra savera hai

Jiski chandni raat hai Asha

Or as Gulzar may say Lata gud ki chaasni hai. Namak ki bori hai Asha.

https://medium.com/media/98a945092cd3abe750654e96521d91c1/href

March 16, 2021

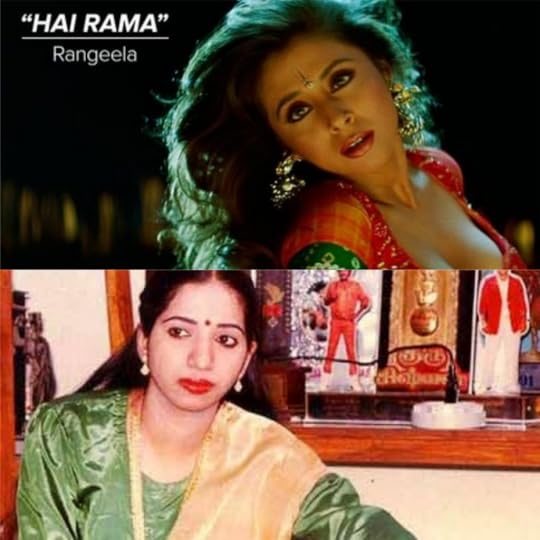

Swarnalatha: How She Was Persuaded To Sing Hai Rama

The classical Rangeela number no one saw coming.

After five days of waiting in a serene beachside cottage in Goa, filmmaker Ram Gopal Varma finally barged into music composer AR Rahman’s room.

‘And?’ he asked, reacting to a bemused Rahman who was watching MTV on the telly.

Rahman had been meeting Varma every night for dinner, promising a tune.

‘It’s coming, it’s on the way,’ he kept assuring an impatient Varma, and compensating it by refilling Varma’s frothy drink.

Rahman did not have a song to shoot the sequence.

‘Next time do one thing. Make sure my room does not have a television,’ Rahman coolly suggested.

An irate Varma wanted to smash Rahman’s face with the remote control he was clicking in Varma’s face to switch his expression to calm.

Back in Madras, Rahman met singer Swarnalatha for the song. A year ago she had sung the Tamil hit number Poraale Ponnuthayi in Mohanam raag for him. It had fetched her a National Film Award for Best Female Playback Singer.

https://medium.com/media/14bd7b7adc19ad3fb2e809a836c1e01c/href‘I have a classical song for you,’ he said.

She beamed.

‘In Hindi,’ he said.

She went cold.

‘Hai Rama,’ she said, ‘What about my pronunciation?’

‘You can do it,’ said a terse Rahman, whose economy of words was only making her sweat more.

‘Yeh kya hua, kyon aise hamey satane lagey?’ she grumbled in her accented Hindi, hinting at its awfulness.

Lyricist Mehboob Kotwal, who was present in the meeting, laughed and began writing in a diary.

Tum itni pyaari ho saamne hum qabuu mein kaise rahein

‘Let’s rehearse,’ Rahman said, playing the keyboard. ‘Speak up, vomit it in Hindi.’

‘Jaane tum ne kya kya socha aagey aagey, hum toh ab darne lagey,’ said Swarnalatha, expressing her fear.

Kotwal wrote some more as Rahman mumbled words to a Purya dhanasri raag.

‘Jaane do na a a a,’ Rahman twisted the raag in a ‘s g, rgmg rsn, pm’ pattern, trying to dispel her fear, and making them sit up attentively.

A few hours later Mehmoob said the lyrics were ready.

When Swarnalatha read it, she realised it looked like a litany of her apprehensions about singing in a non-native language.

‘Now sing it like you are complaining,’ Rahman said, ‘but remember you have no complaints right now.’

‘Think of Sridevi in Kaate nahi kat te yeh din yeh raat and sing to please her,’ he added.

https://medium.com/media/8383592a747ffc22c611c52276d1247b/hrefSwarnalatha smiled and sang her portion without a hitch, arm-twisting ‘jaane do na a a a’ as if she was trying to coyly wiggle her way out of the situation.

‘Perfect,’ Rahman employed his economy of praise and sent her home.

Rahman sent the scratch to Varma.

Varma heard it on his tape recorder and wondered what this messy Carnatic fusion was all about. He flew down to Panchathan Record Inn in Madras and heard it with the complete orchestration — tanpura, tabla, shekere, keyboard, flute, strings, bass, and a whole lot of other percussion instruments and a choir.

He was zapped. Speechless.

All Varma could say was, Hai Rama!

https://medium.com/media/ed1b423440eb63cbda8ca882b415f17c/hrefAlso: Swarnalatha so beautifully singing Hai Rama in 2009, a year before her death in 2010. She had been suffering from Idiopathic lung disease.

https://medium.com/media/35db0d25ae87255b8cd0e0d48be3aa57/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.