Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 5

July 3, 2020

Tribute: Saroj Khan

The dancing star

Photo: Mangesh Pawar

Photo: Mangesh PawarAs a teenager, Saroj Khan featured as a chorus girl in the song Dekho Bijlee Dole Bin Badal Ke (Phir Wohi Dil Laya Hoon, 1963), watching Asha Parekh win a challenging dance-off.

https://medium.com/media/07068b180ae22e0ac3001a0f431ed0b5/hrefIn the film Suraj (1966), she saw Vyjayanthimala, gracefully squash the competition with her moves in Kaise Samjhaun Badi Na Samajh Ho.

https://medium.com/media/e16f6f3239fde26955955ddb224ea420/hrefShe had trained with the best choreographers Sohanlal and Gopi Krishna. She idolised the Travancore sisters.

https://medium.com/media/b125bf7682b80680323c9bca61cf75b0/hrefWatching Sridevi in Himmatwala (1983), she wondered if she would get a chance to work with the actress.

https://medium.com/media/a84509bdd6f4fd9c5648ae0bcfbe0ed4/hrefThe first time she worked with Sridevi was in the song Maine Rab Se Tujhe Maang Liya (Karma, 1986).

https://medium.com/media/981d1e979ecb0aee8382f98f4cf5ac86/hrefMain Teri Dushman in Nagina (1986), was the first time her choreography was noticed. The knee-spin move was tough but Sridevi did it.

https://medium.com/media/ccc143f4d71d46c4f9b37a85e239dc6a/href(Katrina Kaif does a superb knee-slide, perhaps as a homage to that school of dance in the Rekha-Chinni Prakash choreographed Manzoor-e-Khuda, Thugs of Hindustan, 2018)

https://medium.com/media/a3b62897e926b4efd53ae7bdefe7fa11/hrefMadhuri Dixit’s trust in her choreographer catapulted her to become the go-to dance masterji as she was called in an art form dominated by male choreographers. Farah Khan, Vaibhavi Merchant, Geeta Kapoor, Shabina Khan followed.

https://medium.com/media/0df6e6c6ddab4de4485a48851136667d/hrefShe has several songs to display her dance skills but one that I find most becoming of her is giving the actor the ‘chaal’ (gait) of a dancer.

In this dance sequence she wants Sridevi to sway like the moon in the clouds, rustle like the wind in the tall grasses, flicker like the flame in an oil lamp, be firm as earth and fluid as water.

https://medium.com/media/0dea944e54ff58bebe40601b74a787b2/hrefThere are no hook steps. No bol. Only what Saroj Khan knows best: the rhythm of the body in movement to the beats. It is as if the music is in one’s bones and dance its shadow.

July 1, 2020

The myth of the Kashmiri beauty

Men, women, children, and the militant gaze.

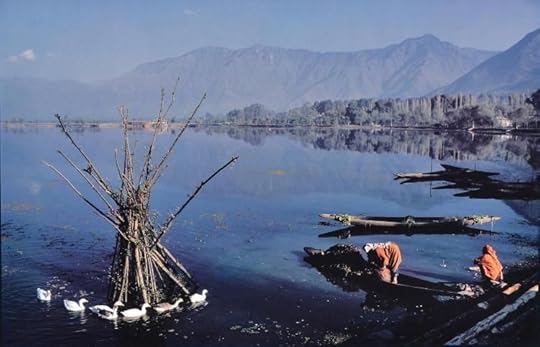

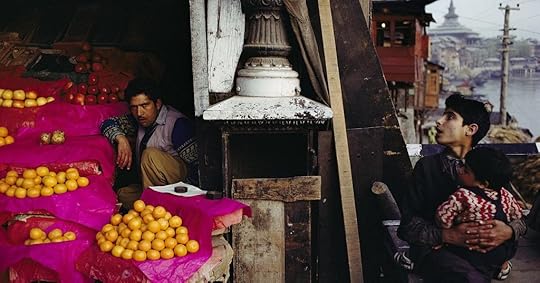

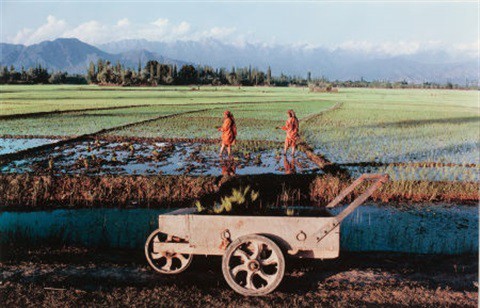

Photo: Raghubir Singh

Photo: Raghubir SinghThe myth of the Kashmiri woman’s dazzling beauty is nowhere more present than it is here in Srinagar — notwithstanding the massive popularity of Katrina Kaif — women are in large swathes absent from any real public presence — as and when you see glimpses of them through fluttering dupattas and burkhas — it remains a preview to hungry eyes.

Where women are beautiful and hidden, there the callous display of their men is intriguing. I see them unmasked — as butchers, woodcutters, bus drivers, vegetable vendors, oarsmen, bakers, wool dyers — in the old and the new — men in a laborious mien — no one is refined, there is no polish, no finesse — these men are designed by a living that makes no small change for vanity.

Raghubir Singh

Raghubir SinghIn a way am reminded of Soviet paintings of the working class — people so bedraggled in their image, they begin to appear brave — skin sallow, upturned lips, downcast eyes — reflecting in their wan faces a disingenuous longing for shade from hardship.

The Kashmiri man’s gaze is intense — bush brow, hollow cheeks, razor slicked jaw line. It’s not uncommon to be bashful to it. A kind of militant gaze of the overzealous — perhaps even a resemblance to the livestock that stares out of a barn at a hillock receiving gales of wind and shower. When I do look at them, sometimes furtively, I wonder about their lives so unloved by the kind of hysteria they would have otherwise received if they were poster boys of the province.

Raghubir Singh

Raghubir SinghWhen beauty goes about unnoticed in the wilderness and like the hangul that is momentarily frozen by the sight of a voyeur — to move ahead unfazed — graceful in its exit — it leaves the hunter crestfallen.

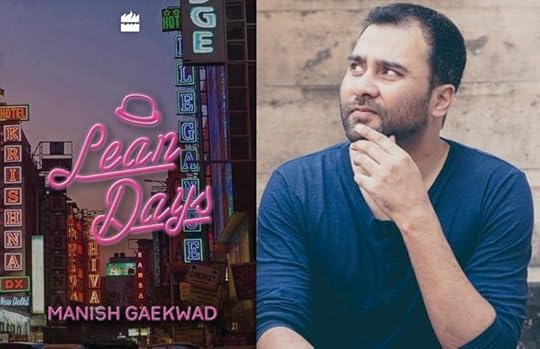

P.S.-I wrote this on July 2, 2012 in Srinagar. It became a part of the Kashmir Days chapter in my novel Lean Days.

June 21, 2020

How my book is trying to enter the bestseller club

Using the Chinese whisper method.

So the book I wrote has crossed its first hurdle. Yesterday, I got an email from the publisher informing me that the book has sold x amount of copies.

Why am I not revealing the x amount? Because some of you will say it’s nothing great. You would have sold more if you had written it. Agreed. You are a genius.

In India, and for a non-starter first-time author like me, one needs to sell 5000 copies to enter the bestseller list. I am not there yet but am inching towards it, despite all the hurdles that the publisher put up against the book.

No promotion, no marketing, no launch, no 5-city tour, etc, etc.

I am not complaining.

The silver lining is there for all to read. Despite it, the book has raced ahead by word-of-mouth through my friends, their friends, friends of friends. I need your help in reaching the 5000 mark, to prove it to the publisher that there are readers if you reach out.

Book sellers, exhibitions, reviewers — they will not help promote it and why should they? They feel that it is a book for queer people and should be segmented and kept at the far end.

I agree about its theme, but I also insist that it should not be labeled exclusively queer. Non-queer people should read the book and discover it is like any other book about the human condition.

Yes, this is an individual initiative, person-to-person. I will have to request you to read this post and mention in comments if you have read the book, own it, or would like to. Let me know.

Online order, your personal review, and rating are the only ways to achieve the 5000 mark into the bestseller club.

Please remember am not doing this to earn from your pocket. I have other sources of income. One writes for love of literature, money is a side-effect if at all it comes, and I have received no royalty so far. If i do get royalty, i promise to use it for a noble cause.

If you must know, in 2005, my first income from writing in a tech magazine went to a girl child’s education in Bangalore.

If you do reach out, we will have to build a network to insure the target can be reached. If you think you can help me accomplish this, it won’t be the first time you did this to contribute to a book’s real purpose — to be read.

In order to help you just have to look at your bookshelf, your friend’s bookshelf, and their friends’ bookshelves and see if my book deserves a place with those who write for money and those who live to write. There is a difference. Some do it for fame. Some because they have no other skill and do it for love. Like Josephine March in Little Women.

June 14, 2020

Tribute: Sushant Singh Rajput

We met in the restobar WTF in Versova. That is exactly how I feel hearing he is no more. WTF!

It takes me back to that evening, when I was enjoying a beer with an actor friend. I was introduced to him. He was hanging out with another actor friend.

Dressed casually, but sporting a hat gave him a standout look. His energy was boundless as he stood at our table, seemingly restless with his spirit or the one he was drinking.

He had debuted in films and was being touted as the next big star. There was no need for me to ask his name. Everyone in the room knew who he was. I was introduced to him as a writer.

Oh, he said, immediately. That’s good. I read a lot too. Raju sir recommended some books I am reading.

He was probably preparing himself for his role in Rajkumar Hirani’s next movie PK.

He rattled off a few names of self-help books that I don’t recollect now but at that time I smiled and nodded, because I would never read them. One must never prevent an actor from discussing books.

I suggest you read these books, he said. I nodded.

I am also reading a lot of science stuff, he said, mentioning A Brief History of Time.

Suddenly, he became a curious case, but before I could say a word, the two handsome men moved away. They didn’t have a table and we were not offering our seats.

I must watch out for this one, I thought.

An intelligent actor is a rare phenomena in the film world. It makes them immortal in the brief history of their time.

I was looking at his photo with MS Dhoni in an aircraft, his interview with ‘Chutki’ Gaurav Gera in a press meet, last night around 2am on Instagram. It did not seem strange then. Here was an actor on the rise.

The world reminds us in mysterious ways who we will be missing next.

A poem he wrote:

तेरी हर एक मासूम हँसी पे

यूं ही मैं अक्सर जी लेता हूँ

खुद के लिए कुछ

जो बचा रखी थी कभी

वो सारी दुआएँ देता हूँ

June 12, 2020

The Making of Gulabo-Sitabo: How The Film Got Its Name

Fatima Begum had a say in it.

Gulabo Sitabo

Gulabo SitaboWe’ll give him a new nose na, said the writer Juhi Chaturvedi.

She and director Shoojit Sircar were deciding on the get-up for the actors.

You are too good, he said. Bachchan sir is meticulous about such things; he has a thick nose for minding his own business anyways.

I know, I heard he invoices his tweets, she said.

For what? He asked.

For his staff, he pays them per tweet they type baba, she said.

No, said Sircar. He can’t be that chindi.

Hah! She mimicked her own laughter and said, Money flattens class.

They were sitting in actor Farrukh Jaffar’s house. They had come to see her for the role of Begum in the film. Jaffar returned from the kitchen with cups of elaichi tea for her guests.

Sircar looked into his bag and said, Shit, I forgot the organic bread.

I told you to pick it on the way, said Chaturvedi. She sounded irritated. Ab peeso chakki ghar jaa ke.

Arre arre, aap log jhagda na karein, the weak-kneed Jaffar stood up from her antique green cushioned rosewood chair to return to the kitchen.

That re-re-reminds me, what w-w-will we do of Ayushmann, he asked hesitantly, trying to divert the conversation.

This exactly, haklana-tutlana, we have to give him one of your nervous ticks, she said.

Jaffar placed a pink cream cake on the table.

Organ jaisa bread toh nahi hai, she said, cake se kaam chala lo.

She smiled like a dowager offering crumbs to the needy.

Chaturvedi sheepishly looked at Sircar, forgetting for a fleeting moment that they were on a strict diet.

Isn’t she perfect? she said, tucking into a slice of ittar-smelling cake.

They told Jaffar they were taking her for the role of Begum.

Film ka kya naam bataya aapne, Jaffar asked.

Fatima Mahal, said Sircar. Film mein aap ka naam Fatima hoga.

Yeh toh rasool Muhmammad ki beti ka naam hai, said Jaffar.

They looked at her and then at each other to keep it together.

Aisa kariye, aap film ka naam badal dijiye, said Jaffar.

They looked at her and then at each other, trying to stay in this together.

Waise toh naam accha hai, par aaj kal ka mahaul toh aap dekh hi rahe hain, Jaffar trailed off.

Nehru ke zamane mein toh log shayad naam sunn kar picture dekhne aa bhi jaate…Taj Mahal, Sheesh Mahal, Khooni Mahal…

Chaturvedi and Sircar smiled at each other.

Fatima Mahal mahal kum aur mazaar zyada sunai padhta hai. Kaun aayega mujhe dekhne?

Jaffar’s chuckle bounced like the laughter of children in a bus riding over a bumpy road.

Film ka naam kuch uut-pataang rakhiye…kuch aaltu-faaltu….jaise Gulabo Sitabo, said Jaffar. Jaise aap dono.

Chaturvedi and Sircar didn’t know where to look.

Shoojit Sircar, Juhi Chaturvedi.

Shoojit Sircar, Juhi Chaturvedi.

June 7, 2020

What The Sad Climax Scene Of Classic Films Reveal

Not Do Bigha Zamin, Pyaasa, Guide, Sholay, Sairat, but Dil Se gets it all wrong.

Dil Se (1998).

Dil Se (1998).Cinema fascinates us but only consumes a few.

I became aware of my obsession in 1998. I was a teenager walking out of a theatre after an afternoon show of Dil Se. I went home and wrote in my diary:

The climax of Dil Se could have been better. Instead of the hero (Shah Rukh Khan) being blown apart, the heroine (Manisha Koirala) could have pushed him away. She could have run away from him. He could have taken a tumble, trying to catch her. He could have fallen down with her green dupatta in his hands, watching her explode at some distance, with the bomb tied to her waist. He could have been sitting in the radio studio, playing a melody as an ode to his incomplete love story. Ae ajnabi, tu bhi kabhi, awaaz de kahin se…

I was rewriting the climax. Such temerity.

I was invested in the moral of the story. What did it tell us about us? If it did not, what purpose did it serve? Art without purpose is like life without meaning.

I was writing without warning. Who was I to tell Mani Ratnam how to make a film? Quite clearly, I was just a fan. I was not yet aware of the concept of fan fiction or else I would have known where I belong. In a trash bin.

My alternative climax sounds filmy but in the garbled mess of that very filmy film it was a beacon of hope (at least to me). The best works do that. They give us the weightless ammo to move on, however irreparable the damage has been. We lick our wounds and strive for better. The end is a start.

Take Pyaasa for instance. What if Guru Dutt’s character Vijay had died on the railway track where a beggar wearing his coat is found crushed under a running train? Even though Dutt returns to renounce fame, his retirement from the stage with Gulabo in his arms is a noble failure that sings to our complicit souls.

Raj Kapoor’s Raj goes to jail in Awaara for killing a man and almost committing patricide. These are serious crimes. The end is bleak, but soul-searching begins. His girlfriend Rita (Nargis) comes to visit him in jail. He has a good reason to live.

Nargis is Radha in Mother India, the long-suffering woman who puts an end to her son Birju’s (Sunil Dutt) derangement with a gunshot in the climax, allowing us to be on the right side of the fence inspite of the heart-breaking cost of justice.

What about Anarkali in Mughal-E-Azam? She is banished from the court and entombed underground, but we also see her being pardoned by the stone-hearted emperor Akbar. Her life is consigned to anonymity but at least she redoubles our faith in love. Pyaar kiya toh darna kya!

A young Dalit boy hurls a stone at a window in the climax scene in Ankur, somewhat similar to the climax in Fandry, both as reactions to unfair treatment by upper-caste men. Sad and violent climaxes but also conversation starters: Who cast the first stone?

Jai dies in Sholay, but what if Veeru died too? Would their dosti still be a paragon? I doubt. Jai‘s legacy lives through Veeru staying alive. It is a story to pass on into countryside folklore.

Sholay (1975).

Sholay (1975).In Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, the proud father could have easily shot down his daughter Simran and her lover Raj to save the family’s honour at the railway station in the climax. It would have made for a grim end to an otherwise enjoyable film, and would not have led to Sairat, where honour killing pulls the rug from under our feet but does so with a glimmer — an infant crawling towards the dead bodies of his parents.

Raju, the tour guide, dies in Guide. Vijay dies in Deewar. What if they had not? The climax would have fallen flat. Raju’s spiritual awakening empowers the film with a metaphysical quality few works of art can accomplish. Vijay’s death in his mother’s lap is his biggest triumph. He is in a good place now.

Satya, and its predecessor Ardh Satya, both have harrowing climaxes. Satya (J. D. Chakravarthy) wants to get a glimpse of Vidya (Urmila Matondkar) before he dies. It will set him free. Om Puri’s cop character Anant in Ardh Satya commits a crime that emancipates him.

Gloom foreshadows the small boy Chaipau (Shafiq Syed) who stabs Baba (Nana Patekar) in the end of Salaam Bombay. It follows Salim Mirza (Balraj Sahni) who blends into the agitating protesters demanding employment in Garm Hava. Phoolan Devi surrenders before a crowd that has gathered to watch her decline in Bandit Queen. Geeta comforts the now-handicapped Vikram (Shiney Ahuja)in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi. The finale musical number in the circus of Mera Naam Joker is suffused with immense sadness. There is a respite of momentary bliss in Nargis serving water to a parched labourer Raj Kapoor in Jagte Raho. The disappearance of Chhoti Bahu (Meena Kumari) in Sahib Biwi Aur Ghulam, the dance of death by Sahib Jaan (Meena Kumari) in Pakeezah, the personal sacrifices of Aarti Devi (Suchitra Devi) in Aandhi, the ostracisation of Umrao (Rekha) in Umrao Jaan, the price of independence for Pooja (Shabana Azmi) in Arth, the retaliation of Sonbai (Smita Patil) in Mirch Masala, Reshmi’s (Sridevi) retrograde amnesia and her cruel return to memory in Sadma, the false imprisonment of Vinod (Naseeruddin Shah) and Sudhir (Ravi Baswani) in Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, the aftermath of the 1993 Bombay blasts in Black Friday. Everywhere, death and grief looms, and at times it is a metaphor that has more that one interpretation in Devdas (all versions), Maqbool, Rang De Basanti, and Kaagaz Ke Phool, hinting at liberty and peace.

Do Bigha Zamin (1953).

Do Bigha Zamin (1953).In Do Bigha Zamin, Balraj Sahni’s family loses everything they have but not each other. Losing their loved ones would have intensified their suffering into yet another relentless wheel spin of hardship. We know that is how it will be but we don’t need a reminder.

Mortality prolongs life in these classic films. The redemptive nature of such art enshrines it into greatness, when it speaks to us directly about the impermanence of life but celebrates its ephemerality. These films with a perfect high-art/low-art balance aspect ratio alter our objective truths into subjective realities.

In Dil Se, if the hero’s bride-to-be Preeti (Preity Zinta) had seen his obsession with another woman and we saw her recollecting her short time with him after his death, then we’d know that all is not lost. That his death was not a waste. That his troubled love story remains alive in her memory as an admirable failure. Perhaps that would have been a more appropriate climax.

Ratnam’s classic film Nayagan finds karma in the bullet-ridden revenge climax. Even Bombay ends on a hopeful note with hands joining to form a chain of humanity to protect the helpless in a turbulent period.

The end of something lost is the beginning of something new to recoup. We can take a bullet but we must survive the fall.Tell us it will be just fine and we will get on with our mundane lives. If that cannot be achieved, then the work of art is never going to endure. Cinema must never lose sight of our loyalty that comes cresting in the comfort of our tears.

Bombay (1995).

Bombay (1995).

June 2, 2020

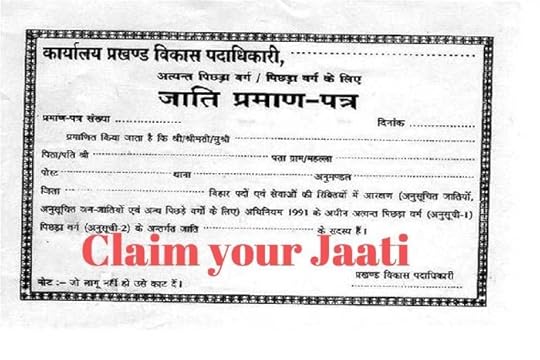

What is your Jaat?

Hurry up before the stock of your caste ends.

No one ever told me about my caste and no one ever asked for it. It was like having a birthmark on a part of my body I could not see, behind my ears.

I have never been aware of my caste till now, although except for once on a train journey a few years ago. I took a train from Dehradun to Haridwar. A man in his late sixties, dressed in a dhoti-kurta sat and with a white tilak on his forehead, sat across. He had a singular thoughtful expression on his face as if he was chewing on the strings of time while it preserved him.

Aap kahan jaa rahe ho, he asked.

Surely he knew the answer but that’s how one makes small talk. After confirming we were headed in the same direction as the train, he asked where I am from.

Bombay, I said.

Naam kya hai?

I said my name.

Gotra kaun sa hai aapka?

My face sank into a double chin.

Jaat kaun si hai aapki?

I don’t know, I blurted, in defence, and in ignorance.

Poora naam?

I said my full name.

Hindu ho, jaat nahi pata, he said in a quizzical tone. Even he couldn’t decipher it from the surname. Yadav hoga.

I understood what this was about. I may have slipped from the varna ranks.

Actually, my father is Muslim, I said, trying to silence him.

Oh, love marriage hua hoga na, he assumed, adding he could sense it from my unshaved beard.

Aajkal ka fashion hai, he said.

Love, or look, I couldn’t grasp what he was reproaching.

After the remark, he went quiet. He could have sounded intrusive if he had asked why I had a Hindu name despite a Muslim father. Trees were flying across the window, the sun was heading up, and warm air was filling the compartment.

Haridwar kyon jaa rahe ho? He asked, changing tact.

I gave the standard touristy reply.

To see the Har ki pauri, I said.

I had seen pictures of the ghat where the Ganga enters the plains. The river has a brilliant emerald tinge descending from the mountains. The water is considered sacred to the Hindus who believe a dip in its cold embrace has curative benefits.

The old man was pleased with my answer. Maybe I was on my way to shed my father’s religious birthmark from my skin.

An old man’s resting bitch face tends to spout myriad truths.

Oh, you will find magic in the waters, he said. The first person you speak to will be an angel to guide you. Remember to try the halwa-puri at Mohan sweets.

I walked from the station to the riverbank. The air was clean, the sun was pleasant, and the chaos was perfectly calibrated to blend in and disappear. I enjoyed the ordinariness of being nobody in a new place.

After observing the musical sounds of the gushing waters, marvelling at its iridescent colour and dipping a toe in its icy fingers, I headed for the treats at Mohan sweets. As I walked away, I watched a boy toss a rope with a magnet tied to it. It pulled coins from the shallow end. Magic.

The salty smoke of deep-frying puris and samosas, shiny orange jalebis, with tea on the side — a classic Indian breakfast had tourists clambering to spot a table. I stood out and ate at one of the standing tables where uncles park their toddlers to reserve the space.

An aunty with tennis shoes peeping out of her baggy blue salwar stood alone, biting into a hot samosa. She smiled at me and small talk began.

She said she was here with her family. They were at another shop behind. She wanted samosa and jalebi. I said as little as possible, keeping the chat brief about being advised to eat here.

She listened patiently and as she moved away casually after polishing her plate, she washed her hands at a water dispenser and said, Koi zaroorat ho to batana.

She left with a head tilt as goodbye.

In Indian culture, one is used to hearing people say that when they are taking your leave. Let me know if you need any help. It is a polite offering when exiting a room. No one buys into the rhetoric nature of the offer.

She was being an angel.

In the years since, the word savarna, or the four forward class of people, has popped up several times on my social media timeline. Initially, it amused me, as I only associated sajna with savarna. I guess for me it still means checking the sajna’s entitlement before getting ready for him. Savarna has become an irrefutable part of our daily online discourse. It makes us check on our own complacency.

My fictional surname Gaikwad was given to me by the principal of a boarding school in Kurseong who misheard the surname Gagade. My mother had to give my father’s name for my admission. She had never been married to my father. She elected her brother-in-law’s surname Gagade. She fumbled to pronounce Gagade a few times and when the principal repeated after her to confirm, he said Gaikwad? She went along with it, nervous that he would reject my admission if she, an uneducated filly, tried to correct him. She had never met a Gaikwad.

Growing up, I associated the surname with the actor Rajinikanth whose real name is Shivaji Rao Gaekwad. I was often asked if I was related to the cricketer Anshuman Gaikwad. Since I did not play the sport, I changed the spelling to the other Gaekwad because I liked the arts and Rajinikanth. The surname also gave me the bloodline of royal lineage from the Gaekwad dynasty of Baroda. I didn’t mind this association as a child. It gave me an air of nobility.

What works for me in a democratic anglophone society will not serve me well in the cow belt extending to all regions lately. For long I have grazed pastures in disguise as a Gaekwad, gae for cow and kwad from kivaad or door: cow door. Although, it is still the best bet. To belong to the Yadava clan gains entry into the Kshatriya club. Second in the hierarchy after Brahmins. I have apparently not been doing too bad with my fake surname.

I am now acutely aware of my jaati, that I belong to a Scheduled Tribe from my mother’s side (Tamaichikar), and to the Muslim minority from my father’s side (Khan). That makes me lowest in the order, along with my personal identity belonging to the queer of caste. Three indelible strikes.

Merit alone has been my jaat so far. If people have been inferring my class status from my fake surname, they are making wrong calculations. As for my true caste, my english-speaking skill has been enough to garner my entry to any upper-class echelon in society. My strong anglophone education has made me indifferent, to not educate myself and utilise the reservation quota that my under-privilege ST status accords me.

The country is regressing to ancient times. Religion is shapeshifting into fanaticism. I may have to rely on magic and angels to survive in the future.

May 30, 2020

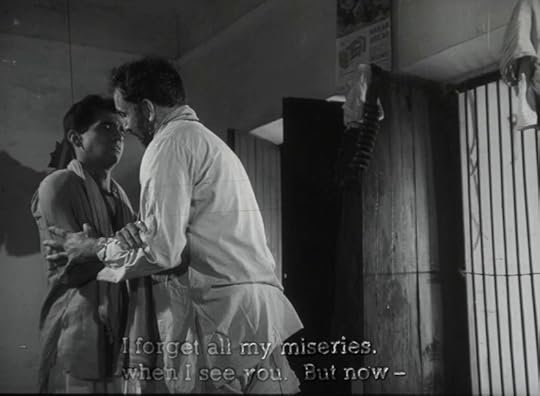

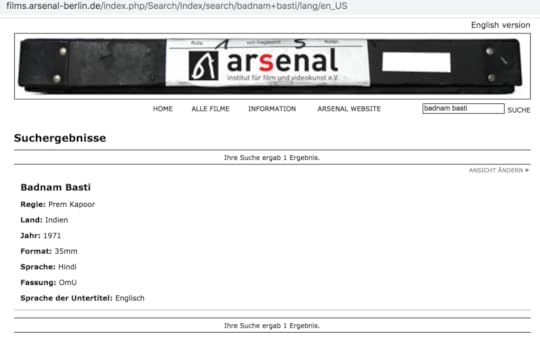

Lost & Found- How India’s First Gay Film Badnam Basti Was Traced After 49 Years Of Mysterious…

Dumped in an archive in Berlin, resurrected in the name of filmmaker Raj Kapoor

I had first read about Badnam Basti in 2008, in the book Same-Sex Love in India.

Published in 2000, the exacting editors of the book Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai combed through poems, books, letters, and biographies in fifteen languages to compile a definitive compendium of the history of same-sex love and desire across the Indian subcontinent.

About the film, they wrote through its main source: Kamleshwar’s Hindi novel Ek Sadak Sattavan Galiyan.

“Badnam Basti created a furore merely because it depicts a truck driver and part-time bandit keeping a young man. The relationship is wholly subsidiary to the heterosexual involvements of both men in the underworld they inhabit, and is visible in the novel mainly in the young man derided by others as effeminate and a hijra.”

The furore was short lived.

At that time I wondered why the furore died down so soon. How come I had never heard of this film? I had so far prided myself in knowing a fair bit about Hindi films. Even the obscure arty ones coming out of the purple haze and blue smoke of FTII playgrounds.

In 2016, working at Scroll.in, the film editor Nandini Ramnath said to think of unusual films to write about. I suggested Badnam Basti (1971). She had not heard of it. I mentioned the source and she got cracking, providing me with names and numbers of the film’s crew to meet and interview.

I emailed Ruth Vanita for more information, but she said that was all she knew too. She had not seen the film.

Furore.

I then read Kamleshwar’s novel in English translation (rapidly) and in Hindi (slowly).

Over two weeks, I was able to meet Hari Om Kapoor, the son of Prem Kapoor who directed Badnam Basti. Hari Om was employed in an office in Andheri West. He had a file of paper clippings about the film but little information about its making.

Where can I see the film, I asked. He had no clue where it was. He had no negatives. He said the disappearance of the film from his house remains an unsolved mystery. He also had a penchant for wearing over-sized hats.

I thought meeting him would make him unearth some forgotten rusty iron trunk under a bed and pull out a dusty round box of film. Classic film cliché.

If that had happened, then it would have been a rather short article. The film’s producer NFDC and the archive vault NFAI had said they had not heard of the film. Hari Om was my only hope to extend furore.

Next I met a director’s assistant whose name I am forgetting. The man was sprawled on an old-style gaddi in a house in the suburbs, yelling at his wife to fetch tea. I asked him to connect me to Nandita Thakur, who plays the role of Bansari, a nautanki dancer in the film. He told me she was hospitalised with an ailment. It was not a good time.

The film’s cinematographer R Manindra Rao, an FTII alumnus, met me in a coffee shop and described the shooting process in great detail. He had high regard for Prem Kapoor’s intellect but the same respect could not be granted to his filmmaking skills. Rao said they fought a lot because Kapoor did not have a background in film. Rao decided to go rogue and shoot as it pleased him. Rao’s cheery disposition was an advantage I could misuse for random interruptions as I filled his cup of coffee with excess sugar.

Lokendra Sharma (brother of television anchor Rajat Sharma) said he was a production assistant on the film set. I met Sharma in his Lokhandwala apartment. He said he was a young lad who had joined the crew in Mainpuri, UP, to gain film experience. He ratified Rao’s claim about Kapoor’s inexperience. He also drank his tea as if in spiritual limber.

The film’s lead Nitin Sethi had died in 1985. Second lead Amar Kakkad met me in his apartment and was happy to discuss his role in the film. He acted in only two films, the second being the 1982 film Lubna (not about Lubna Adams) in which he is the hero’s (Kanwaljit Singh) friend. Furore (for sidekicks getting sidelined). Tea arrived on a tray with biscuits. Yum.

So far so good, but meeting them had made me curious to see the film (and stave off tea).

I wrote the article and submitted it to the editor for corrections. She said all the information needed was there but the framing was off. So she swiped her magic wand and it came out all the more better.

The article was published in Scroll in February 2016.

Hari Om Kapoor was not pleased with the article. He said it belittled his father. I had not included the not-so-polite words of some of the crew members. Only one that called Prem Kapoor a vegetarian — meaning a prude who later went on to make his only other non-veg film called Kaam Shastra, perhaps to shed the tag.

https://medium.com/media/208fb2fd8aa8aa557df3cddbf716b1f8/hrefI had written extensively without seeing a single frame of the film! This was going to be the end of the story of the resurrection of Badnam Basti.

Furore! Furore! Furore! (Sounds like something Nazis would say, hailing a despot)

Who knew that the furore was hibernating in Germany? Uh oh!

Three more years of gumnaami passed.

In November 2019, Simran Bhalla, a PhD student in film studies at Northwestern University, US, and a graduate fellow at the Block Museum, emailed me saying that she had found the film.

Whaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat?

Followed by a calm furore or a shoulder massage.

A 35mm negative print that was nowhere to be found was in an archive in Berlin.

She said she had read the Scroll article and that’s when the museum started checking with archives world over and located it. They stumbled on Badnam Basti in a listing of Raj Kapoor’s films in the Arsenal archive website.

I immediately wrote to the director of the National Film Archive of India and said please get it from the Arse…nal. Kind of funny that a film about queer love is stuck in an arse.

Führer…I mean furore!

Suspense shadowed for a few months when Simran did not write back to update about the 35mm print. Was it damaged?

On May 5, 2020, she wrote back saying the film was in poor condition but the kind people at the Arsenal archive digitised it for online streaming.

The Block Museum had wanted to show the film in their venue but the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown made all lives, and free shows impossible.

So they decided to stream it on Vimeo on May 8.

I had to register on an event site and was awarded a password.

Simran told me to check IST for the screening.

I wound up my body clock to the alarm of Oscar morning. I was up at 5am to watch it, to sync with American CDT.

With groggy eyes and full enthusiasm, Badnam Basti was finally seen.

Lockdown had trained my senses to keep celebration low key. I did not jump on Twitter. The film was ho-hum. Don’t read me wrong. It was as expected. Now I had the task of making sense of it. Like fellow citizens getting brain-freeze tasks.

Little furies.

I wrote furiously, not with anger, at speed. The first draft was ready in the evening. I emailed it to a newspaper editor to consider running it in the daily. The editor asked for time and replied in two days that the team did not approve it. Another editor from the same team said they will get back. Two weeks passed. I texted and emailed. No replies.

I consulted a few friends in the media and sent it to other editors. Lockdown also meant uncommissioned work was no longer welcome. After a few rejections, Firstpost picked it and the furore continues.

https://medium.com/media/14638926a56ff3c7a730fdd981bd021f/hrefWhat do I think about the film?

It has an excellent soundtrack. Listen to this track Sajna Kaahe Nahi Aaye. Singer Ghulam Mustafa Khan sang it, written by Virendra Mishra, and composed by Vijay Raghava Rao.

It sounds a bit like Ajhun Na Aaye Baalma Saawan Beeta Jaaye and Aaja Sanwariya Tohe Garwa Laga Doon

Exquisite!

Another haunting melody Taaron Ka Mela Bhara Hai Gagan Mein was sung by Satish Bhutani.

Of course I am digressing a little, but if you have come this far, please persevere with a tiny bit of furore…

https://medium.com/media/317947ce7dc1814ed1a49970db1e4837/hrefBut what about the film, right? Is it any good? For those of you who are dying to see it.

It may not be perfect but it is pioneering for trying. The biggest crisis facing the crew even while making the movie must have been how to present the subject without offending anyone, In that, it triumphs, with some gorgeous visuals.

But more importantly, Prem Kapoor was trying to circumvent around the minefield of the censor board and get past it with the film’s queer content. There was no point-of-reference for such a theme. Previously, gay characters were either shown as desexualised eunuchs guarding a king’s harem, clapping in festive ceremonies, or as leading men who crossdressed and behaved effeminately to mimic the affectations of a woman vying for a man’s attention. Queerness was played up for laughs.

What Kapoor was trying to do was to portray queer men without them wearing their sexuality on their sleeves. Laundebaazi, or the practise of an older man taking a young lad under his wings is a common social register in North India without recrimination from society. This form of pederasty, so clearly expressed in the novel, dimmed in film translation because of his indecisiveness on how much to show and how much to hold.

Cinematographer Rao said the debutant director was so shy on the film set that he could not instruct Nandita to wink at Nitin in a nautanki dance sequence. Explicit romantic scenes between the men were a danger zone they could not trespass.

Why is Badnam Basti an important addition in the annals?

I didn’t say anus, but The Times of India review was a pain in the arse. It called Sarnam’s character a “sexual deviant,” thus implying that homosexuality was considered an abnormality and mirrored the mood of the country. This is debatable.

Laundebaazi was treated with utmost sensitivity in the book and in the film. It did not invite such an extreme reaction. What the newspaper did was indulge in yellow journalism to stir a furore that may have never taken place at all.

The queer characters were not tormented by their sexuality, they did not seek validation from parents and society, they were not tortured, they did not die for it and far from a happy ending, the film left it open to multiple interpretations. Homosexuality was not shown as a criminal activity or a disease. It was tender, passionate, romantic. Had it been seen more, it would have been praised for the positive representation of queer people.

In 1971, the year of its release, the incumbent (or incompetent) Congress government was too busy furoring with Pakistan over the liberation of East Pakistan. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was more invested in saving her throne after a rift in the party threatened to topple her prime-ministerial dictatorship. Haathi Mere Saathi, a film about an elephant (maybe a metaphor) was the top-grossing film.

There were far too many pressing issues than a small film with rank newcomers that could have caused a furore. I wish it had though.

The film deserves to be seen and ranked as a forerunner, albeit with a re-cut, because at least a bunch of newcomers were showing signs of progressiveness in their work.

How did Badnam Basti nestle in a lair for so long?

Badnam Basti was sent to the Mannheim Film Festival in West Germany in 1972, where it found a safe repository to hibernate.

A negative of the film was recently deposited at the National Film Archive of India, but the content is yet to be ascertained.

This is good news and bad news. You will have to wait for a film festival to pick it from the archive and screen it or you will have to work at NFAI or Arsenal and steal it like a blue-blooded cinephile.

The furore must dance now, till eternity.

May 17, 2020

Notes on a Pandemic: Happy in Lockdown

Reflecting on my privilege while my family slums it out in the crisis.

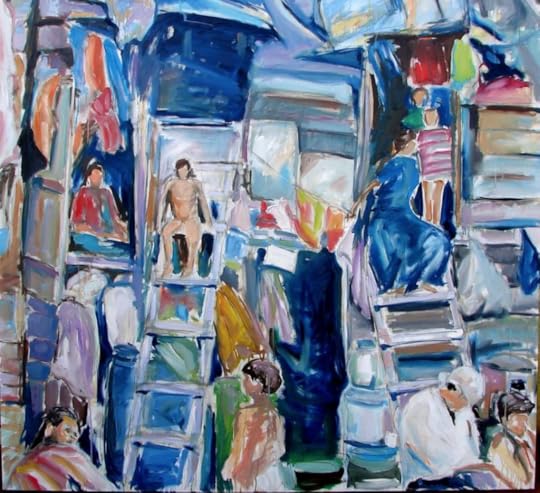

Painting: Dharavi Slum by Caoimhghin O Croidheain

Painting: Dharavi Slum by Caoimhghin O Croidheain(Note: An edited version of this essay was first published in Himal Southasian.)

On March 1, I moved into a rented apartment in Kolkata. A Chinese lady and an Italian man had vacated it in the afternoon. There was no reason to panic.

I fell ill the next morning.

One day it was a runny nose. Another day it was a red-hot fever. Followed by immense fatigue yet another day. What were these symptoms of?

The foreigners had looked fit and fine when I had met them to collect the house keys. No one was wearing a mask. They were beaming smiles. We chatted at a respectable distance as we normally do with strangers. We did not shake hands. They said namaste and folded hands.

Foreigners adapt quickly.

The lady reached her home in Shanghai and reported to our landlady that she had tested negative for the contagious virus. So did the Italian man.

A week passed. I had recovered from my symptoms. I had not left the apartment. Living alone has insulated me from seeking company. I did not know anyone around. My only neighbour was a family living in the ground floor that I rarely saw when I stepped out occasionally for essentials. I was using my convalescing period to begin writing my book. Then the news of the lockdown began to float.

I called my mother who was at her friend’s house in Jaipur. I told her to return to her house in Kolkata. She said she was going to Pune the next day. She would leave from there in a few days time.

She reached Pune. The lockdown was announced.

She was staying in one of her sister’s chawl room. I told her to leave the slum Bhat Nagar in Pimpri-Chinchwad with the help of her relatives if she could.

Her nephew is a rickshaw driver. She said his rickshaw was damaged. Her niece is a sweeper in the Pune Municipal Corporation. My mother said she would not step into a municipality van fearing it would be a minefield of other scabrous diseases. She tried to shirk it off saying she is in a better place than being dumped in a garbage truck.

I was trying to convince her to reach Baramati, where another sister lives on her farm. My mother could have a better survival chance there than in Pimpri which was going to record a morbidly high number of cases.

It was foreseeable.

Bhat Nagar is where the poor, the untouchables, the so-called ‘scourge of society’ live. The place is so filthy that Dharavi is a dream sequence featuring Madhuri Dixit in a Sudhir Mishra film.

Am not overstating it.

https://medium.com/media/32f1557cc39d68402008954e9ca625c5/hrefOver two decades ago, I was seventeen when I stepped out of Pune station and asked a rickshaw driver to take me to Bhat Nagar. My kanjar-samaj relatives had informed me those two words were the complete address: Bhat Nagar.

The rickshaw driver scanned me and asked: Aap ko udhar kyon jaana hai? Aap toh padhe-likhe lagte ho. Why do you want to go there? You look civilised.

That is why I was worried when my sixty-year old mother got stuck there in the lockdown.

My cousins work as security guards in banks and hospitals, sweep roads, make and sell illicit liquor and weed, drive rickshaws and live outrageously (if somewhat harmoniously) with squalor.

Bhat Nagar is infested with pigs, cows, horses, donkeys, goats, ducks, cats, dogs, chickens, birds, rats, cockroaches, spiders, lizards, fleas, bees, mosquitoes. I may have missed a monkey or a bat.

Not a single flower can grow there without being compromised.

Painting: Waiting by Zahid Mayo

Painting: Waiting by Zahid MayoI lived there as a teenager, trying to spend my boarding school knowledge on the children and adults, advocating cleanliness, hygiene and education. I was treated like an entitled prince from a foreign state. I was offered a small bucket to fill and defecate on a vast tract of barren land across the road.

Aap ne baraf dekha hai! You have seen snow! They fawned when I told them about my school in Darjeeling. They thought it was in Switzerland. Like in a Yash Chopra movie.

Not one person believed things could be better if they made a small change. Instead, I think I learnt to not take myself so seriously. Life is precious but it is also unpredictable. A little reckless abandon can perhaps give it character. I left Bhat Nagar after a few years of failure. I went on to pursue my own career instead of trying to change their lives. It takes a village. They were the villagers.

Today, while I sit alone in the Kolkata apartment, worrying about my mother who is diabetic and had high blood pressure, all I can do is call her every day and remind her that she is going to be fine if she takes all the necessary precautions.

Breathe from your gut, I tell her.

I also remind her to be happy. That is the only thing I have been telling her my entire life.

Look at me, I say.

I have never told her I am sad even when I have had lows. I know how quickly it will escalate. I did not tell her about my sickness on moving into the rented apartment. It would have trebled her bp and she would upset at least a few in the family by constantly obsessing about my health.

Isn’t that exactly what we are at present dreading, a community paranoia?

I try to look happy. Always. It is a common trait I may have unconsciously picked up in Bhat Nagar. I now think about it and wonder how it may be the only survival trick I learned from the community.

And look at all those people who are so different from us, I tell her. Their communal laughter is a thing of imperishable beauty.

I never went back to Bhat Nagar because I could no longer live like an urchin. I felt that unexamined life did not dignify my education. I had to be ‘somebody’ when my relatives were trying to turn me into a hooch seller, a bellboy, and a salesman in a garments store.

I am, like all of us, currently re-examining how we treat the marginalised. How expendable they are. This pandemic is renewing our ties with them. As we are now trying to acknowledge their invisible presence amongst us, their lives as inextinguishable from the privileged — it has been my good fortune as a writer to have emerged from that same abysmal place with no hope, to be able to express with artifice and magnify the lives of those who soldier on with quiet persistence. But that too will have to wait.

There is nothing I can do for them right now, just as in my teenage years I was trying to be a lone crusader. But what I do know for sure is that as long as the people of Bhat Nagar are together, they will watch over my mother and keep her in good humour.

That is a luxury my privilege simply cannot guarantee.

May 7, 2020

POEM: The Cyclist

I cycled my way home

It took me a summer

To cross state highways

Policemen and hunger

When I reached home

It was not standing there

Neighbours said it collapsed

The house had no one to live for