Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 9

August 13, 2019

Sunidhi Chauhan: A Sweet Hereafter

Ishq mein khud ko bhula ke jhoom. She did that for a brief period.

Sunidhi Chauhan was in a tearing hurry to get married. She was eighteen.

She was shooting the music video of her pop song, Pehla Nasha, and was smitten by its choreographer-director Bobby Khan. Mummy had advised her to gift her virginity only to her husband.

‘Sona,’ Bobby affectionately called her, ‘Babes, just walk naturally ok,’ he instructed her for a shot while filming on a highway outside Bombay.

He was inspired by the video of Madonna’s song Don’t Tell Me, pleasing his own sona, ‘Darling, just be cool when you walk, don’t be conscious of the camera, do anything you like; rustle your hair, smile, touch your ear loops, look around and smile at car drivers hurtling past, ok?’

Sunidhi nodded. She had seen the Madonna video and had practiced the ‘walking style’ — a chunky portion of the choreography of which included walking with her thumbs tucked in the fronts of her denims, lurching forward like a lazy big cat on a deserted road, lip-synching, and never directly looking into the eye of the camera.

Sunidhi thought this was great choreography for her song, so alag aur hatke from aam Hindi pop songs otherwise replete with semi-clad dancers, she quoted to a television reporter who had come to interview her on the shoot.

Could she know any better? It was her pehla nasha. She was in love.

In-between shots, she would text the choreographer-director from her van: Good Shot, Stunning Choreo, Great Visuals, but didn’t get any replies.

Sunidhi could not understand why he did not respond to her virtual compliments, while constantly preparing her for takes with amatory words like ‘sona, babes, darling, madonna.’ Madonna! What a fantastic comparison to be considered in the same league. Madonna Chauhan! Could a man blow hot and cold at the same time?

At dusk, when the team was wrapping up, Bobby Khan knocked on her van, let himself in and offered to drive her home. They played her song en route. She said she didn’t want to go home. Bobby asked, ‘Where then?’

‘Jahan tum le chalo,’ she cadenced, injecting ideas in his visor head. ‘Ok’ he adjusted his cap, accelerated and sped his car. The fuel in his wallet could take them only so far.

Her song Pehla Nasha on repeat mode had put Sunidhi to sleep. She woke up on Baga beach, yolk sun spreading in her eyes; her dark pupils aglow as orange orbs. Bobby was sitting next to her, smiling, waiting for her to wake up.

She leaped out, ran barefoot into the waters, shrieking and jumping with joy, no person in sight besides them. This is the most romantic thing anyone had done for her.

She ran back to the car, dragged Bobby out and pulled him into the water. They fell in, got drenched, stood up, and peered into each other’s eyes and kissed. Sunidhi felt love, aching for marriage to consummate this feeling.

She could not invite her parents to her wedding. They would not accept her husband.

She cried out, ‘But I still want a traditional wedding, I want my mother to dress me up in a joda, my father to do my kanyadaan, my brother to pick up my doli. I want all of these things Bobby! Can we not replace our parents with people who love us unconditionally?’

He made no effort to mediate. She got her friends, television hosts Tabassum, Annu Kapoor, and singer Sonu Nigam flown in for her wedding.

The pipsqueak Tabassum, a favourite on local television, a corn-fed pleasant woman who had made a reputable career dishing barn house friendly advice to lesser sentient beings was the first person to spot Sunidhi’s talent when she saw the little girl singing at a temple in Delhi. Ever since, Sunidhi believed the portly woman was an angel, her godmother.

Annu Kapoor had been more than vocal on the singing reality show Meri Awaz Suno, where he hoarsely announced to the judges his faith in Sunidhi’s talent. She won. He was to play father at her impromptu wedding.

Sonu had sung some duets with Sunidhi and she looked up to him as her bhai. Though all of them consulted that she was taking a rash decision to marry, they supported the beach shack wedding with much gusto.

Tabassum danced, Annu drank, Sonu sang Ruki Ruki Si Zindagi Jhat Se Chal Padi in Sunidhi’s chirpy voice. Her life was speeding in the wrong lane.

The pop album tanked. No one heard the music. No one saw the music video. The marriage lasted one year.

Bobby was using her to bolster his own career as a filmmaker. She was allowing herself to be used.

It took her two years to reclaim her spot in the singing pantheon.

At music composer Pritam’s insistence, she tapped into the tunes of a new film project and chose one track of the four he had listed for her to pick. She chose wisely.

Virginity, marriage, divorce, estrangement, privacy, fame, security — she had snapped out of adolescence with the song that seduced the nation. It was her screaming admittance, a sweet exhortation to reinvent herself.

Sunidhi returned to the roost with Dhoom Machale. A hailstorm of awards followed.

After her divorce she had issued a statement to the press quoting irreconcilable differences and the reason for separation being they both ‘wanted different things from life’.

Bemused readers knew what to expect from the songstress even then, a tradition of playback decorum adhered to.

Her fans she now considered her only family, never forgetting to thank them first at every event where she collected a trophy.

‘Because it’s not my family, not my friends, it is you guys who love me unconditionally,’ she sniffled.

She was back and was never going to be taken for a ride ever again.

https://medium.com/media/3023bcaa3ed3787753cb98d92378691e/href

August 10, 2019

Reshma: Fragile to Music

The Lambi Judai melody that defied boundaries.

In 2006, popular Pakistan-based folk singer Reshma was amongst the first with her family of six to board the Lahore-Amritsar bus on her way to the Golden Temple.

It was the first bus service introduced as part of a peace process between Amritsar and Lahore. With a prayer on her lips stained with betel nut juice, her ears reddening, heartbeat pacing, her feet felt lighter. There was a spring in every step.

Reshma, the nomad woman hummed throughout the journey. She was returning home with a chant in her aching heart. The Sitara-E-Imtiaz of Pakistan was navigating her way through the broken landscape of the imagined state and mending it into the shape of her faith; it was in between these two lands where her wanderlust voice roamed.

On her way, she recalled the time she was flown into the country to sing a song in the film Hero in 1983. She had requested musicians Laxmikant–Pyarelal not to use their famed orchestra piece. She asked for minimal music, a matka preferably. She sat on the floor of the recording room, and with the mike on the ground, she drummed on the matka a languorous rhythm, singing Lambi Judai.

When she came to the line Hijr ki oonchi deewaar banayi in the lyrics, she would sing Hijr ki oonchi deewar girayi in a high octave.

Laxmikant would interrupt her and repeat the correct line to her and ask her to take it from the top. Eyes perpetually shut, Reshma sang in a trance Hijr ki oonchi deewar girayi. She never got it right. A miffed Laxmikant walked out.

Pyarelal, the gentler of the composer team somehow cajoled Laxmi to return to the recording, and to respect her feelings. Perhaps she was internalising the lyrics. Reshma kept babbling in her charming rustic Punjabi about her illiteracy.

Reshma, after hearing Pyarelal’s mithi-mithi gal as she rekindled, eventually picked up and sang in her dune voice Hijr ki oonchi deewar banayi with renewed vigour. And just as she stretched the last syllable of the word banayi on a top scale to the beat of her hand, the matka broke. As if to impugn a symbolic breaking of glass omen — walls, boundaries, borders, fragile to music.

Who has not heard the soulful Lambi Judai?

The song that gave us Reshma, the indisputable gypsy voice of our own wandering souls.

As the bus wound through the changing landscape, she could see the barren deserts, violent winds, panihari songs and makeshift tents that have been her way of living, never tiring of her long road home, and carrying her mournful mountain voice to her resting place. Ever since she was born in the year of the hijr (separation), the lambi judai of 1947.

https://medium.com/media/7fd0e91e3292fda7c7bd089274896ca9/href

August 5, 2019

POEM: A variation of All You Who Sleep Tonight

आज की रात हमे नींद नहीं आएगी

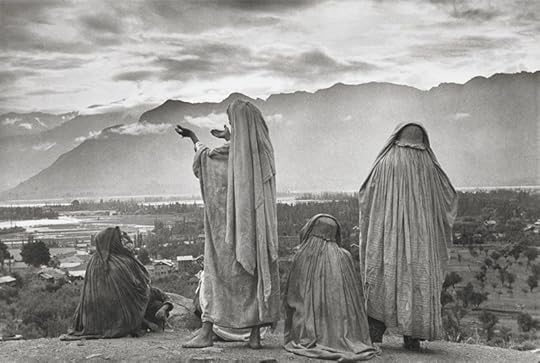

Srinagar, Kashmir, 1948, Henri Cartier-Bresson

Srinagar, Kashmir, 1948, Henri Cartier-Bressonआज की रात हमे नींद नहीं आएगी

यह सोच कर की वह कैसे सोयेंगे

जिनके घरों में सुबह नहीं आएगी

आज की रात हमे नींद नहीं आएगी

यह सोच कर की जब कल आएगा

तब तक शायद बहुत देर हो जाएगी

आज की रात हमे नींद नहीं आएगी

यह सोच कर की अगर हम सो गए

तोह जागने की घडी फिर नहीं आएगी

आज की रात हमे नींद नहीं आएगी

गजर की आवाज़ चार-सू बज रही है

आज की रात गोया लौट के न जाएगी

***

Aaj ki raat hamey neend nahi aayegi

Yeh soch kar ki woh kaise soyenge

Jinke gharon mein subah nahi aayegi

Aaj ki raat hamey neend nahi aayegi

Yeh soch kar ki jab kal aayega

Tab tak shayad bahut daer ho jayegi

Aaj ki raat hamey neend nahi aayegi

Yeh soch kar ki agar hum so gaye

Toh jaagne ki ghadi phir nahi aayegi

Aaj ki raat hamey neend nahi aayegi

Gajar ki awaaz chaar-suu baj rahi hai

Aaj ki raat goyaa laut ke na jayegi

Gajar: alarm, Chaar-suu: four directions, Goyaa: as if

August 3, 2019

Kishore Kumar: What The Heart Wants, The Head Delivers With Guilt

How the singer loved and lost Madhubala.

‘Haal kaise hai jaanab ka?’ she giggled, splashing water on him.

He tapped his straw hat, ‘Kya khayal hai aapka?’

‘Hai, tum toh machal gaye oh ho ho,’ she stood up, tilting the boat with her weight.

He arched on his left, and sat down on the flat board in the bow, ‘Yun hi phisal gaye, ah ah ah.’

‘Cut,’ director Satyen Bose yelled from a distance. He was seated with his film crew on another boat, instructing the camera operator to switch to a new angle. ‘Joldi koro, I want to take far shot, far from here,’ he huffed.

Kishore Kumar began yodelling.

Kumar and Madhubala were shooting for a song in the wobbly boat in a placid lake. The boat was being paddled by a stuntman who was not included in the camera’s frame. The stuntman also appeared oblivious to the actors’ off-screen romance.

‘But you know, I cannot marry you, I will only give you distress,’ she called for Kumar’s attention.

The stuntman looked puzzled, trying to deconstruct her dialogue from one end of the boat.

‘I don’t care,’ Kumar inched closer to her face.

‘I have a hole in my heart,’ she added.

He grabbed her right hand, opened her thumb, took off his hat, and placed it on a whorl in his hair.

‘Do you feel something?’ he pried.

‘Na,’ she grew curious.

‘Rub it,’ he tamped her thumb on his head, putting pressure and rotating it like a driller machine.

She wrinkled her face to give him a sign that she felt nothing.

‘Then how do you expect me to feel the hole in your heart. I see heart, I don’t see hole.’

She laughed at his cunning; he had a child’s guileless charm, there was innocence in his appeal of a kind that can hardly be called romantic, but fetching to the maternal instinct in her. She found herself ready to adopt this grown up brat.

‘Behki, behki, chale hai pawan jo udde hai tera aanchal,’ Kishore teased.

‘Chhodo, chhodo, dekho-dekho, gore-gore, kaale-kaale baadal,’ she flirted, trying to dismiss his affection.

They docked at the waterfront. Kishore was outfoxed by her playfulness, ‘Kabhi kuch kehti hai, kabhi kuch kehti hai,’ he said as he stumbled out of the boat.

At their wedding, he held her shy face by her chin, holding her luminescent smile in his eyes, ‘Zara nazar toh samabhaalna,’ he winked.

Their civil union had upset a lot of people including Kishore’s parents and first wife Ruma. She did not want to divorce him so he could bring home a notun toy to play with.

Ruma had taunted Kumar during the bou bhaat ceremony at home, when Madhubala stated she could not cook a grain and laughed the loudest at her own admission, while others frowned as her indecent display of milky-white teeth and contagious honesty.

For a month, Kishore and Madhubala, both dour-faced, addressed each other as Pagle-Pagli in the Kumar household where Madhubala had a tough time adjusting to his family’s demands of her as a model housewife like Ruma.

Madhubala, who had always been a star since eleven, could not breathe in the stifling atmosphere of the strict Ganguly family. She decided to confront Kishore about it. He was not blind to it either, though he could not stay apart from his joint family.

They agreed to separate, she moved out of his house, back to her Bandra bungalow which was not far from his. They would call each other on and off, sometimes going out on what Kishore called, ‘boy-girl dates.’ He would yodel on the phone to capture her giggle.

Madhubala enjoyed this the most; marriage was over, courtship continued.

‘Pagli…pagli…kabhi tuney socha raste mein gaye mil kyon?’ he would prod her over candle-lit dinner at a glittery five-star, away from the spectre of marriage and its accoutrements.

She would light up, tinkling her glass of claret with his, ‘Pagle…pagle…teri baaton baaton mein dhadakta hai dil kyon?’

They would burst out laughing at each other’s silliness; how they both loved playing it out, their dreary unfilmable lives were in these nimble moments, floating with gaiety and under-table footsie.

‘Hod-aay-e-ee…yud-aay-e-ee…ud-aay-eee,’ Kishore would bleat at his table, often setting the waiters in a scramble. Her toes would reach for his to stop. ‘Woohooo,’ he would empty his glass in one big swig.

The same year she went to London for medical treatment and was told by doctors that there was no cure for her gun-shot heart. She had at most a year to live. The news devastated her; she came back, stopped working and sought to distance herself from everyone.

When Kishore got wind of her poor health condition, he tried to intervene and move in with her, but she would have none of it.

‘Kaho ji, kaho ji, roz tere sang yun hi dil behlaayein kya?’ she quipped. She thought it could get worse, the more she saw him, the more her heart would bleed.

‘Suno ji, aha suno ji, samajh sako toh khud samjho, batayein kya!’ he would plead, bowing, pointing at the hole in his head. Her giggle sounded hurt. Blood crawled up on her lips in spittle. Kishore’s head pounded with agony.

After her death, Kishore Kumar’s fame as an eccentric artist became a lore. To give it further credence, as he began to stun visitors with erratic behaviour; biting a producer’s hand, locking a financier in a cupboard, talking to the trees in his bungalow’s front yard, he put matters to rest when he placed a signboard outside his door. No one disturbed him.

The hole in his head was spreading. The board read, ‘Beware of Kishore’.

https://medium.com/media/68bc8fd42cbe0fd57f11c716b547f59c/href

August 1, 2019

Bhai Jaan meets Sahib Jaan

Pakeezah becomes Park Kiye Jaa.

Sahib Jaan sings, ‘Chalte chalte…chalte chalte…yun hi koi marr gaya tha…yunhi koi marr gaya tha…sarre raah chalte chalte…sarre raah chalte chalte…wahin tham ke reh gayi hai…wahin tham ke…’

‘Wahin tham jaa,’ Bhai Jaan roars.

‘Kya hua Bhai Jaan, itni buri lagi aapko awaaz hamari?’ she sniffles.

‘Awaaz?’ his voice echoes, ‘awaaz hai ke public service announcement, yeh kaisa gaana hai jaan-e-mann?’

He gets up to leave.

‘Thade rahiyo oh Bhai Jaan re, thade rahiyo.’

‘Lagta hai traffic police ka bhoot ghus gaya hai,’ he sniggers.

‘Aisi baat nahi hai Bhai Jaan.’

‘Tan tana tan tan tan tara, chalti hai kya nau se baarah?’ he shakes his belt.

‘Mausam hai aashiqana…ae dil…’ she mulls but quickly switches to another fast tempo song, ‘Chalo bhai jaan chalo…chand ke paar chalo’

‘Moon-woon pe nahi jaana hai. Tujhe Aksa beach ghooma doon, bol fatafat, ae chalti kya?’

‘Paon beach par rakhungi toh mailey ho jayenge, Bhai Jaan!’

‘Chal chal, ghadi-ghadi natak karti hai.’

He runs down the spiral staircase. Strains of ‘Kaun gali gayo bhai jaan’ can be heard emanating.

He speeds off with his bhai log.

The accident occurs.

Sahib Jaan is summoned in court to depose as witness, being the last person Bhai Jaan met.

Sahib Jaan coughs, clears her throat and sings like a jailbird, ‘Inhi logon ne…inhi logon ne…inhi logon ne ,’ she stops.

The prosecution lawyer asks, ‘Inhi logon ne kya?’

‘Lilaah!’ she faints, slips into a coma for 13 years.

Bhai Jaan utilises this period to renovate her kotha into a jazzy clothing store, with free and safe parking facility.

When she wakes up, she is told he has become human.

She has no memory of her past.

All she keeps repeating is, ‘Jo kahi gayi na mujhse…jo kahi gayi na mujhse…woh zamana keh raha hai…woh zamana keh raha hai…’

‘Kya?’ the nurse asks.

Sahib Jaan cannot recollect. She hums, tapping her bare, unadorned ankle, ‘Chalte chalte…chalte chalte…’

https://medium.com/media/23c83237054d11efa220b62b9e71be5e/href

Ek Jaam Meena Ke Naam

Poems for the tragedienne.

Meena Kumari was born today (Aug 1, 1932) and remains immortal.

Dard se mehruum nahi hain hum

Jala toh hai apna bhi daaman

Khush-nasibi se abruu qayim hai

Mehruum: deprived, Daaman: hem, border of dress, Abruu: dignity, Qayim: steadfast

दर्द से महरूम नहीं हैं हम

जला तो है अपना भी दामन

खुशनसीबी से आबरू क़ाइम है

…

लोगों में

जीने का सलीक़ा

खलल गया है हमें

मर कर ही हमने

लोगों तक

अपनी दास्तान पहुंचाई है

ज़िन्दगी की मरमरी आवाज़ पर

अब कहाँ हैरत होती है

लोगों को

Logon mein

Jeene ka saliqa

Khalal gaya hai hamey

Marr kar hi humne

Logon tak

Apni dastaan pahunchai hai

Zindagi ki marmarri awaaz par

Ab kahan hairat hoti hai

Logon ko

Saliqa: good manners, Khalal: distress, Hairat: surprise, wonder

July 30, 2019

Mohd Rafi: In The Last Emperor’s Court

The singer raises the dead with his rendition of Na Kisi Ki Aankh Ka Noor Hoon.

Rafi and wife Bilquis.

Rafi and wife Bilquis.Before Mohd Rafi could record his voice for the tune of Na Kisi Ki Aankh Ka Noor Hoon, he asked the music composer S N Tripathi, “Kis ki ghazal hai?”

Pat came the answer, ‘Bahadur Shah Zafar’.

Rafi saab refused to sing it.

He said he had not been to the last emperor’s dargah, and therefore didn’t know if he had the king’s blessing to do justice to the dirge. Tripathi thought he was being foolish, but insisted that Rafi should read the lyrics to get a feel of the emperor’s last wish.

Rafi saab read and wept inconsolably.

Tripathi seized the opportunity to win him over. ‘Socho, what Zafar must have felt, when he cried out with his ghazal. Rafi, you must give him voice. Who knows after you sing it, Zafar will indeed bless you. Many have sung this ghazal, but in your voice it will be Zafar’s reign, his pledge. You will be the sotto voce of the last Mughal emperor of India. Yours will be the last golden voice of this era.’

Rafi thought of Tripathi’s balderdash and entered the recording room with clay feet.

He faltered every time he had to sing the lines:

‘Aiy faateha koi aaye kyoon

Koi chaar phool chadaaye kyoon

Koi aake shamma jalaaye kyoon

Main voh be-kasi ka mazaar hoon’

(Why should any prayers for the dead commence?

Why should anyone offer flowers at my bed?

Why should anyone light a candle for me?

That helpless mausoleum I have become)

Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Bahadur Shah Zafar.The room would chill, Rafi would get goose flesh. His throat would begin to dry, as if Zafar’s ghost had entered the room to agree with Rafi’s vocal chords.

After a couple of attempts, Rafi warmed up to the eerie atmosphere in the room and delivered. He told Tripathi that his voice was echoing in his ears as if a thousand Rafis were chorusing in his head. A thousand singing spirits had invisibly sung along with him.

The film for which this song was recorded, Lal Qila, was released and quickly forgotten.

Many years later, it was reported in a local Burmese daily, that someone had playfully broadcasted Rafi’s song on the announcement system during the evening prayer call at the Bahadur Shah Zafar dargah in Yangon, Myanmar.

A miracle appeared above his dingy shrine just some distance away from the dazzling Golden Pagoda. A white orb of incandescent light hung in the air over Zafar’s tomb. Pilgrims flocked to offer prayers. In a few hours, the light had weakened and died, but ever since, Zafar’s mausoleum was considered no less special than a Sufi pir’s grave.

Scholars have fiercely contested that Zafar has not written the ghazal, and the miracle was a farce. Discredited, disillusioned, one might say Zafar is haunting the enclosure of his sardgah (empty grave) in Mehrauli where he wished to be buried with his predecessors.

It is rumoured that if you play a tape of Rafi’s rendition at Zafar’s sardgah, you can feel the emperor’s presence.

He will manifest in some form; a darkening of cloud to grey, a raven twitching on a tree, a dip in temperature — all are omens that the emperor is nearby, crying out to be embraced.

India, his home, where he has been entombed far away from, under the oppression of the British tyranny, Zafar finds himself exiled in a foreign land and locked in a hurried tomb.

Freedom and return comes to him in Rafi’s heartfelt poetic voice, each time someone cares to listen.

https://medium.com/media/6278681e1aac709b7ff6ab52d561b49b/href

July 29, 2019

Sonu Nigam: The Inner Voice

With a little nudge from his potty seat, he went from anal to oral…

Composer-duo Nadeem-Shravan invited Sonu Nigam to their studio for an impromptu music sitting. Nadeem explained, ‘Yaar, we want you to break the mould,” without delay when he arrived at their door.

‘Mould?” Sonu responded, “Main kuch samjha nahi,’ his eyes widened in surprise as he stepped into the cool corridor leading to their recording room.

‘Dekho,’ Shravan offered him a chair with a nonchalance that Nigam found oddly comforting, ‘Yeh Rafi saab ki tarah gaana, theek hai, par hum chahte hain ke tum hamare liye ek naye andaaz se gao.’

Nigam signed up.

He was given the lyric sheet and asked to take it home and rehearse. He was told to develop a new style in singing.

Super thrilled, Nigam rushed to his room to sit with his harmonium and practise. He locked himself in, deaf to his mother’s constant pleas to join them for lunch — the sweet fragrance of gatte ki sabzi and matar pulao assailing him to surrender.

He had made up his mind; he would not step out till he had cured his voice from imitation.

Hours passed as strange sounds escaped his room, his family often startled in the midst of their siesta, wondering if he was wringing a cat or hammering a nail on his tongue.

His harridan mother could not be calmed. She cursed his experiments, ‘Hey bhagwaan, kab akal aayegi iss besurey ko, haraam kar diya mera sona.’

‘Nalaayak, nikhattu,’ she would repeat and recline back on her pillow once the jarring sounds from his room receded. This cycle repeated itself into the evening when the agitated woman could take it no more and began banging on his door, ‘Sonu beta, naashta toh kar le, gala sudhar jaayega tera.’

Nigam felt wretched each time his mother knocked and bothered him. His stomach twisted. To drown her voice, he locked himself in his bathroom, pulled his pyjamas down and sat on the throne. He began stuttering the lyrics.

‘Yeh dil…dee-waa-naa…dee-waa-naa hai yeh dil,’ coaxed by the stress on his sphincter. He was aiming for both, constipated as he was, Nigam exerted with more force, creating a vacuum in his stomach.

‘Dee-waa-ney ne…mujh ko bhi (aah)…kar da laaaa…dee-waa-naa.’

The ‘aah’ was a glottal sound nudged by a splash in the bowl that spurted toilet water on his privates, tingling a sensation he thought fit to add to the lyrics.

His bowels began to murmur, his voice rose from his larynx. His inner voice was clearing out of the mist. Nigam sang freely, robust and breathless in his tenor.

‘Maine uske sheher ko chhoda, uski gully mein dil ko toda, phir bhi seene main dhadakta hai yeh dil…(aah).’

The ‘aahs’ kept punctuating the lyrics.

He flushed like a hangman cranking a lever. The whooshing sound of tsunami water in the commode was oceanic music that lifted his spirit. He felt like the lonesome turd circling on foamy surf in the pot, it would eventually find its way. It was the sign he needed to see.

He flew out of his room, into his parents’ bedroom, hitting a C note for the chorus lines, ‘God saves the world …World saves man…Man saves the heart…Heart saves love,’ waving an invisible baton, conducting a high-mass orchestra.

His mother, frightened by his pompous performance, shrieked, ‘Hey bhagwaan, mere bete par shaitaan ka saaya padh gaya! Subah se kuch khaya bhi nahi tha.’

Nadeem-Shravan

Nadeem-ShravanWhen Nadeem-Shravan heard Nigam sing in this new firing-on-all-cylinders style, they were zapped.

‘Holy crap!’ Nadeem felt a bullet rush past, ‘This is awesome dude. bullet chal gayi,’ Nadeem loved the sound of bullets in the morning perhaps.

Shravan wanted Nigam to record it immediately. The composers set up the arrangement and Nigam took up the mike in the recording room, waiting for them to give him his cue.

In the short interval between the overture and his vocals, Sonu looked at them through the glass panel, trying not to envision how he had cracked the song.

They were discussing his murki (musical embellishment). Shravan said, ‘Aur yeh Sonu ka chhota sa ‘aah’ hai na, kamaal hai, iss ka alag nasha hai gaane mein. I like this boy.’

‘Aagey nikal gaya, bahut door tak jayega,’ he averred.

Nadeem agreed, “Bullet ki raftaar hai uski ‘aah’ mein, seena chhalli kar deti hai, kasam se,” he said. He knew a lot about bullets.

In his absence, Sonu’s mother was scrubbing and polishing his toilet seat, sprinkling Harpic, pinching her nose as she tried to flush the lonesome turd that refused to slip out of view.

https://medium.com/media/f76ae2806c8c9c2059d6e0d66b421f07/href

July 22, 2019

Himesh Reshammiya: The Making of a Sphinx

A bloody nose links the singer-actor to the sphinx in Giza, a nose for greatness.

Fed up of the flak he was getting, Himesh Reshammiya decided to do something strange, something impossible of him.

He walked into filmmaker Pooja Bhatt’s production house and had a word with her.

Pooja rolled her eyes and spewed, “Why me, go to Mahesh Bhatt to make a film for you!”

“He does not make films anymore,” Himesh tried to reason.

“He interferes, he ghost-directs!” she snapped.

Himesh sulked, but Pooja wasn’t going to keep her cool.

“Go to Vikram Bhatt, he’ll need someone more horrific than him to sell his films.”

Himesh looked downcast, and was willing to bear the barrage of invectives.

“Mohit Suri is a cousin, go to him; he’ll make a film about Internet porn or some such, and cast you as a lusty trafficker.”

“Bas!” Himesh stood up, holding out his fist in her face, “Maine kuch din pehle apki picture Paap dekhi. Bahut accha laga. Aapke film mein ek ruhaaniyat (spirituality), ek sufiana soz (sufi pain) tha jisne ne mere dil ko ek suroor diya. Mujhe laga ke aap ke saath kaam kar ke mujhe spiritual transcendence milega.”

Pooja gulped. Big words, she thought, for a small man.

Himesh continued, “Maine Paap dekhkar soch liya tha ke agar aap mere saath film banaye toh uske baad chahe mera career chale na chale, yeh tasalli toh rahegi ke hum dono ne milkar kuch alag kiya. Duniya se judaa, khuda ki tarah.”

“Wah,” Pooja widened her amazed eyes, ‘Duniya se judaa, khuda ki tarah,’ she gave it a thought. Only god could have prevailed, common sense was elsewhere.

Tears welled in her thick kohl-lined eyes. She sat stunned in her seat, pensive, not aware that Himesh was reaching out for the door.

“What will we call the film?” she asked the disillusioned entertainer.

He turned around, his new wig firm in place, unshaved jaw turning in slo-mo to give her an appealing shot of his bereaving side profile; face hung down, he looked at her big moist eyes and huskily said, Kajraare with such a solemn feeling that she immediately released her pent and let her smudging kohl licked tears run. She was sold.

“Aashiq bana diya aapne toh,” she thought, but only after she watched him strut away. She dare not utter it to him.

Shooting was far from easy with Himesh. Pooja was no stranger to fits of fury, having previously slapped her actors on the sets, torn clothes of heroines to shreds — her rage had lost her a few good roles even in her own acting days, when she walked out of films because the choreographer’s expression of come hither was bizarre.

Pooja was a dictator on the sets. Some spot boys sprayed dicktator on her chair at one such outdoor shoot. She worked with an unmindful resolute to herself, her current goal was to finish the tortuous shooting of the film.

Camel tow.

Camel tow.During the shooting of the song Rabba Luck Barsa in Egypt, Pooja had to ask her cinematographer to keep panning out as Himesh kept lip-synching without feeling, with one single pained expression throughout. Pooja would yell into the loud-speaker, ‘Himesh, expression do, even the camel following you seems to be singing better, Rabba Fuck Barsa!’

Himesh endured all her tantrums and demands because he believed he was onto something good, that Kajraare would establish his acting credentials. The Bhatts might not have a hit track record but the towering performance of their actors never goes unnoticed. This is the least he could ask for, after giving a hat trick of flops, launch after re-launch.

For the title track, Kajra, kajra, kajraare, the unit went to shoot at the Pyramids of Giza. They dangled Himesh on cords and hoisted him on the head of The Great Sphinx to get a sweeping panoramic visual shot.

Himesh asked to be dropped gently through the disfigured face of the Sphinx and wanted to stand in the centre of the face, where now was remnant chips of its missing nose. The famous Sphinx nose that no one in recorded history has seen, as legend has it that a Sufi apostle, outraged at the peasant offerings to appease the stone idol for their harvest, lopped it off many centuries ago.

Had Himesh suddenly become the grand, epic missing nose? Lawless in Arabia, someone chided Pooja for hanging him up there, precariously perched on the missing nose. She said it was destined. One missing a nose and the other known for it alone.

In the centre, he outstretched his arms, a la SRK in Sooraj Hua Madham. But just as he began posing, his nose started to bleed. Hot spumes spiralled down his nares. The ever-optimistic Himesh saw it as a good omen from the gods that his hard work in the scalding heat; his physical and mental exertion would not be in vain. Rabba was barsaoing luck.

He swabbed the stem of blood flow with an end of the keffiyeh head scarf he was wearing. Each time he opened his arms to simulate flight a simoom in the desert would hiss; a stinging sandy draft blew in his face. Which he found dramatic and hoped it was being captured on film, down below, some distance away.

The loudspeaker had stopped working, and Pooja had no way to scream at Himesh, stranded atop, in his own filmy ruins. She could not draw his attention towards her to give the right shot, and he, oblivious of her instructions, was mucked in blood and sand.

Pooja lost her cool. She found a huge, square glass panel in the prop van, scribbled something with a permanent marker, and asked one of her clumsy spot boys to show it to him.

He read, ‘EID’ and thought Pooja was contributing to his fortune, it was a good, auspicious day to mount the Sphinx. He looked for a faded moon in the heat of the sun. He stood still, and prayed, raising his hands in the sky as men do during namaaz. She wanted him to DIE.

Pooja called for pack-up and set going with her crew to the hotel for rest. By the time Himesh crawled down, everyone had left, except the Sphinx, still standing behind him when he walked his way to the hotel.

At short intervals, he would turn to look back, and wink at the Sphinx, ‘You rock!’ he would exalt once in a while, thumping his fist in the dead desert air. The Sphinx, unmoved, had withstood worse ignobility and looked through him.

In the hotel he asked for a doctor to visit his suite, to inspect him for blood clots in his nose. There were none. This was an even better sign, a miracle. He tipped the doctor, when the doctor, amused at his endurance braving nose, quipped, not to fret, “Just get it insured if you worry so much,” he smiled on his way out.

An august evening at a screening of the film as Himesh stepped out of his luxury car into the wet drizzle on the red carpet, he slipped and fell on his nose. Hundreds of gathered fans gasped but no one dared to laugh.

Himesh chuckled to distract his fans from his bleeding nose which he adroitly shielded with a kerchief. Everyone cheered and clapped in the aisles after he resumed posture. Surely a good sign, he swaggered in bleeding but ready to croon Rabba Luck Luck Luck Luck Barsa, Rabba Muck Barsa.

He looked as expressionless as the Sphinx since centuries, although assured that his nose was insured and would outlast him.

https://medium.com/media/29d782b4ea5a6b8b4897a73f7291c5b8/href

Mukesh: A Denial Of Legacy

Imitating singer K L Saigal impressed no one, least of all actor Raj Kapoor who changed his life.

The first time K L Saigal heard Dil Jalta Hai Toh Jalne Do, he tried to recollect when he had sung that song. It was an era when every young man looking for a break in playback for Hindi films emulated Saigal. Mukesh was no stranger to this brain fever.

For his first recorded song as a playback artist, Mukesh had sung Dil Jalta Hai, imitating Saigal.

Saigal, who happened to hear the song on radio, failing his memory, returned to his chore, having dismissed the song as no mean feat if memory did not help him place its origin.

Mukesh, when he heard of Saigal’s predicament, felt swell that the maestro could not tell between the two, failing which, Saigal had then carelessly placed the song in his own heap of innumerable hits he would only later perhaps have a passing recollection of.

Saigal’s stamp meant everything.

Thereafter, Mukesh decided never to sing in Saigal’s voice and find his own. It was not going to be an easy task to follow. He would subconsciously slip into imitative mode when he sang, impinging each song with the nasal twang that was so becoming of Saigal’s quiet exit.

Music composer Anil Biswas, for whom Mukesh had sung solos, tried every trick in the music book to help him exorcise Saigal’s spirit from his spleen. He would give Mukesh lighter melodies to display his range but the public was in no mood to hear him come into his own.

It began to irk Mukesh, that he should be introduced at film events as the voice that replaced Saigal. He was outraged less out of dishonour towards his idol than from his sense of propriety. Hitherto, he decided to launch himself as an actor, as Saigal had successfully done, and thus, be able to put a striking, handsome face to his voice.

His plan backfired.

There were no takers for his acting chops. His effort to produce another film, lay in the cans. It was a case of misdirected vanity and in the years that Mukesh invested to primp his image, Mohd Rafi and Talat Mehmood had earned stripes that were marked for him. Music composers, wary of his self-indulgence, had begun to hire them who were least interested in acting and had original voices.

Things came to such a turn, that Mukesh’s children were turned away from school because he did not have the required money to pay for their tuition fees. His idol worship had ruined him greatly. Saigal had died in these intervening years and yet his legacy loomed large over Mukesh’s fate.

Mukesh then approached Raj Kapoor, who he had previously sung for. ‘Ek shart par,’ Raj shot back, ‘Tum sirf mere liye gaoge.’ Who was Mukesh to refuse at this point? In return he got Mera Joota Hai Japani, in the film Shree 420.

The song was a marked departure from his sonorous style; it wore its heart on its tattered sleeve. Mukesh disliked the clownish lyrics. ‘What drivel, mera joota hai japani, yeh patloon englishtaani, what form of ridicule do I have to abase myself with?’

Mukesh, Raj Kapoor.

Mukesh, Raj Kapoor.At the music recording, Raj Kapoor sensed his annoyance and asked him to think not of himself while singing but of Raj’s comic face.

‘Sing with a smile Mukesh, this is not about your choice, it’s about my screen presence. Henceforth, when you sing for me, it will mirror the deep pathos of your voice with my winning smile on-screen. That is the combination I want; for people to go back from the theatres with a song about their loves, their lives, their passions and worries, all of which resonates with a be-fikri, a living in the moment hedonism.’

Raj Kapoor was right. Russians were demanding the song be played at The Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Mukesh was back. This time, only more sovereign in thought, jubilant with the success of his new song.

Its global impact helped him discover his new voice, his own, free from influence, and ready to fend for his family. This second coming was not to be shrugged off as just a passing phase. He understood he had to keep this tempo constant, if not soaring, not dipping also.

When Filmfare decided to hand out trophies to singers, he was the first recipient for a song very dear to his heart, Sab Kuch Seekha Humne, Na Seekhi Hoshiyaari from Anari, filmed on Raj Kapoor’s impish smile.

Soon, the actor, Mukesh, the Saigal-clone singer, was forgotten, replaced by the playback artist Mukesh, who was the voice of popular film star Raj Kapoor. Musicians could not think of using any other voice for Raj Kapoor. This insured steady income for Mukesh’s family of wife and five children. Mukesh got so busy working, his family life suffered.

He began touring the west, spreading as far and wide as he could, his new-fangled voice emboldened to improvise Awaara Hoon to Kunwara Hoon for a bunch of beaming women sitting in front rows, lusting over his virginal confessions.

At one such concert tour in America, he died from a heart attack. Lata Mangeshkar who was touring with him, brought his body back home for a state funeral.

On hearing of Mukesh’s sudden death, Raj Kapoor eulogised, ‘I have lost my voice.’ Fittingly, Mukesh’s last recorded song was for Raj Kapoor’s film Satyam Shivam Sundaram.

Naturally, someone in Mukesh’s family was going to take over where he left. His son, Nitin Mukesh, bought it upon him to carry forward his father’s blazing glory. With Mangeshkar’s support, he notched a few duets in his early years, but it was not before the eighties when people began to take notice of the son.

The portly son, dressed in shot-silk kurta, a shawl draped over his shoulders, would walk unsteadily across a stage at a concert, clear his throat, and pay homage to his father through a song he had moderate success with, Zindagi Ki Na Toote Ladi. He tried to sound ethereal, a chain of melody spiralling heavenwards.

Audiences would raise their hands up and sway, trying to conjure images of Mukesh in their head. Nitin would sing feebly, his voice compassing between an infant’s prattle and a fawning boy attaining puberty.

This was his best Mukesh imitation.

https://medium.com/media/d612ab14b748c29c5d3089515c9a8e47/href