Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 11

March 17, 2019

Alisha Chinai: A Siren Song

Kajra Re, Kajra Re, Mere Kaare Kaare Naina, she sang her way out of the mess

Alisha Chinai was presiding over lunch.

Shankar, Ehsaan, Loy; their tongues wagging at the takeaway from Lucky restaurant, the men were trying to concentrate on two things: food and faff.

Chinai was explaining her run-in with foe Anu Malik. She was recounting a traumatising incident.

‘Aisi nazar se dekha uss zaalim ne chowk par,’ she said.

Gulzar saab, strident in voice, jabbed a knife into a piece of mutton chop, prised it out of the silver foil container, and raised it at half-mast, ‘Humne kaleja rakh diya chaaku ki nok par.’ His face widened into a toothless grin, his fuddy-duddy glasses steamed.

‘Bawaal ho gaya!’ Ehsan flung his hands up in the air, following it with a plethora of ‘wah wah’ for Gulzar saab’s ingenious wit.

Loy screamed out, ‘Raita phail gaya,’ tilting a small bowl of streaming yogurt into his plate of chicken biryani.

Shankar drummed his swollen tummy as if it was a tabla, the rotund shape of which it had taken over the years. He would propitiously beat tunes on his belly and compose songs. His body had become a significant acoustic in tandem with his thaap.

‘Dhin tanak dhina, dhin tanak dhina,’ Shankar began beatboxing, issuing vocal percussion sounds, the use of drum beats, rhythm and musical sounds escaping his lips to form a metre.

It was such an inspired coming together for all of them that they tore into their naan rotis and butter chicken with renewed vigour; the table had to be emptied soon, the harmonium had to be played out, a rehearsal was incipient.

While everyone gleefully chomped, Shankar kept drumming and twisting his head to and fro like an owl, flitting in and out of a trance, producing a background score for luncheon thrills.

He performed an infant’s game of food percussion — beating his chest with chicken lollypop (kir-dha kir-dha kir-dha kir-dha), spooning his gravy for a baton (ta-dha ta-dha ta-dha), clapping his naan slices for cymbals (ta-ki-ta dhoom). The final flourish spluttered enough gravy for everyone to rise up.

Things got a little rough and out of hands during the rehearsal. The three amigos, along with the ever-benign Gulzar saab were circling Chinai with thunderous claps and ear-piercing whistles. They touched her and leered and passed her around in their arms like a consolation trophy they had won for making a mess of their lunch.

She felt like a drugged lioness in a cage being entertained by four mad ringmasters. She could snap this minute if she wanted to. All she had to do was to reach out and bite the hand of the one she favoured but she realised it would only put her back into song-less days of melancholy.

Collecting herself, her bag, her stole, her shoes they had knocked off in their delirium, hot tears burning her rosy cheeks, Chinai broke free and ran out, leaving these crazy men to bring the house down with their endless rapture of song and dance.

Left to Right: Loy Mendonsa, Shankar Mahadevan, Gulzar, Ehsaan Noorani.

Left to Right: Loy Mendonsa, Shankar Mahadevan, Gulzar, Ehsaan Noorani.The four men, heads up, watching the ceiling fan circle round and round in their dilating retinas, were oblivious of her exit. An errand boy walked into the room, switched the fan off and helped the elevated men float back to earth, ‘Maidum chali gayi,’ he punctured their enthusiasm.

‘What the f…’ Loy grew frumpy. Gulzar took off his glasses to examine her absence. ‘Kya kar diya maine…oh ho ho ho ho…’

Shankar jangled his flubby flab. ‘Kuch karo Gulzar saab, galti ho gayi…we need that girl, it’s her voice am telling you, that oomph, that sultry silkiness, her diphthong, no one can do it better than her, we need Alisha,’ he said.

‘Dude, did you see her thong?’ Ehsaan tapped on Shankar’s drum belly.

A day later, Gulzar saab telephoned her.

Chinai was reluctant to come around. ‘Dekhiye Gulzar ji, main aapki bahut qadr karti hoon, par uss din jis tarah inn logon ne mere saath behave kiya…aap toh jaante hi hain na…woh Anu Malik ke baad…main thoda darr si gayi hoon…I am scared…I don’t want to compromise.’

Gulzar assured her he had a solution. She agreed, if only he would be present at the recording, ‘Kyun ki main aapki bahut lihaaz karti hoon,’ she said, deliberating over the word lihaaz when she could have said respect.

In the recording room, Chinai seductively read out Gulzar saab’s improvised sher, ‘Aisi nazar se dekha uss zaalim ne chowk par…humne kaleja rakh diya chaaku ki nok par.’

Her voice released pheromones; a salty chemical cologne with a dewy lingering scent of sweet grass. The vapour hovered, tickling the chilly temperature in the room.

The music for the track had been prearranged, and it was going to be her one-take recording. Gulzar saab, who stood at the music console, was tying a black satin sash, blindfolding the three music composers, to emasculate their response.

Shankar, at the whiff of Chinai’s sexy voice entering his ears and triggering a chemical reaction in his brain, swung into action — tailing her sound to grasp her by her waist he imagined he was now holding. Loy and Ehsaan began twirling, grappling with invisible muses of the air. Gulzar saab took off his glasses, and giving Chinai a thumbs up, put a knot behind his thick ears.

Everything operated smoothly after that. She sang, she danced, she pirouetted out of the room, arranging the song on repeat mode and leaving the blinded men in looped carousel.

https://medium.com/media/1183d58bac770d1aef0eaa76db9bc6f0/href

March 11, 2019

Shreya Ghoshal: The Persuasion of Song

Born on 12 March, the birthday girl received her best gift when she was abducted by the Mangeshkar sisters

The housemaid was peeling onions in the kitchen for kanda poha, while Lata Mangeshkar sat on the jhoola in the verandah overlooking the imaginary flyover at her Peddar road apartment.

The maid turned the knob on the radio and the first strains of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan saab singing Bhor Bhayi Tori Baat Takat Piya filtered out to soothe Lata’s frayed nerves; the stinging aroma of the onions was blinding her eyes.

‘Aha,’ Lata cleared her throat, ‘Radio cha sound wadhwa (increase the volume),’ she called out to the maid, who immediately adjusted the volume to fit Lata’s narrow ears.

‘Who is this girl?’ Lata wondered when she heard Shreya Ghoshal accompanying Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Saab. ‘What a perfect foil!’ she thought of the girl.

Lata was livid as soon as that thought passed. ‘How come I was not asked for the duet?’ she sulked when the song was over. ‘Radio bandha kara,’ she instructed the maid.

‘Asha, Meena, Usha,’ she yelled in the direction of the living room. Her voice had not even boomed back to her when the three bleary eyed women stood upright in front of her jhoola, open for interrogation.

‘Tuhe gaana aikley agodar? (have you heard this song before)’ she asked.

‘Ho,’ they admitted their guilt.

‘Hya gaanyacha sangeetkar kon? (who is the music composer)’

‘Rahman,’ they gulped.

‘Hee porgi kon ganari? (who is the girl singing)’

They looked at each other, synchronised, and said, ‘Shreya Ghoshal’.

‘Aana tila itte, mee pan baghte kai bolayachay tila, (bring her to me, let me hear what she has to say).’

The Mangeshkar sisters with brother Hridaynath.

The Mangeshkar sisters with brother Hridaynath.Lata ordered them to leave that very instance and produce the accused before her. She would judge to decide if the girl was indeed made for singing.

The Mangeshkar sisters draped their favourite silk kashtas, wore mogras in their buns and headed out. Lata asked them to instruct the driver to avoid the flyover. They nodded, fully aware that no flyover existed under Lata bai’s nose.

They reached Shreya’s apartment in Lokhandwala after a long stretch on the western express highway, but not before enjoying a zip and an uncontrollable cackle through the smooth sea link. Asha, being the most forthright, rang Shreya’s doorbell.

Before Shreya could react to the stalwarts at her door, the sisters wrapped her in Lata’s unused nauvari and bundled her in the lift. With the help of their driver, who had parked the car just outside the lift door, they stowed her in the trunk of the car and drove off.

Shreya was unwrapped before Lata still swinging in her jhoola, clicking her tongue over piquant lemon pickle. ‘I heard you sing, who do you think you are, you want to replace me?’ Shreya was too petrified to say anything; she simply nodded her head and looked downcast. ‘Who is your Guru?’ Lata inquired. ‘Sanjay Leela Bhansali,’ Shreya squeaked.

‘Ugh, that man is waiting for me to die to have another cathartic movie experience!’ Lata spat out the bitter lemon seeds in disgust.

‘He will have my ghost sing to him, but not me, what a phony…anyways, Rahman sure knows how to use a voice, he is the only composer today who gives me songs my age, I like singing loris for him, but to put you in the league with Bade Ghulam Ali Khan saab reminds me of the time I watched Khan saab during the recording of Mughal-E-Azam songs. I just wanted to be blessed by Khan saab. It seems like you got the chance because of this remix business and auto tuning,’ she said.

‘Can you sing me a note from Bhor Bhayi?’ Lata asked.

Shreya hesitated, sought a glass of water and began, ‘Bhor bhayi tori baat takat piya’ hitting as many as three octaves when the emptied glass began vibrating gently. ‘Bas,’ Lata raised her left arm.

Shreya didn’t know what to say. She stood quietly, hoping to find out at the end of it, what this was all about; she wouldn’t dare upset the melody queen. Asha who was standing behind Shreya, began texting Rahman, ‘I want another Rangeela Re number.’

Meena-Usha drifted into the corridor towards their bedroom, chorusing ‘Apalam chapalam chap laayi re duniya ko chhod teri gali aayi re aayi re aayi re.’ Resigned to their fate, they sang with a spring in their hearts and a bounce in their feet. “ Ho duniya ko chhod teri gali aayi re aayi re aayi re,” they echoed.

“I hereby appoint you as my successor,” Lata blurted without a hint of smile on her face, adding ‘Do you know what the Gujari todi raag is?” just so that Shreya would not be able to fully grasp the miracle of this moment.

Shreya affirmed in the negative.

Shreya was asked to keep Lata’s unused nauvari as a gift. She was sent along with the driver to her house. Shreya rolled down the window and put her head out of the car while crossing the sea link, elated. She asked the driver to drop her at the busy market square in Lokhandwala. It was an unusually hot day for summer. She walked into a Baskin Robbins outlet, mulled over the selection of colourful ice cream on display and decided to settle for her favourite flavour of strawberry in a waffle cone.

Licking it broodingly, she walked her way home. With each absorbed lick the knowledge sank in of what Lata Mangeshkar had said to her. “I hereby appoint you as my successor.” Shreya wanted to sing to the cone, but it would melt if she did, she’d miss its dependable gifts. Of course she had trained in the raag but what did she care about the Gujari todi right now. This was heaven.

https://medium.com/media/c82de76fc2644a9b65ddae79e882116b/href

March 4, 2019

ग़ज़ल\Ghazal

Trying (if not doggedly) to follow the format: beher, matlaa, maqtaa, qafiyaa, and radiff in all shers

East Village Ghazal, Salman Toor.

East Village Ghazal, Salman Toor.***

सांस में आते रहे सांस में तुम जाते रहे

दिल की बेक़रारी दिल में बरक़रार रहे

कौन चाहे के तुम्हे देख के शर्मसार हो

बेअसर न हो नज़र में इतना खुमार रहे

है क़र्ज़दार कई जो सुबहोशाम आते हैं

वक़्त बेहिसाब मगर तुम पर निसार रहे

दिल-इ-मुज़्तरिब में खिले जो आसार थे

हो हसीन न सही ला-इलाज फ़िगार रहे

यह वह घडी है शाम-इ-वस्ल की मनीष

रुखसती के बाद भी जब तेरा दीदार रहे

***

बेक़रारी: Restlessness

बरक़रार: Continuous

शर्मसार: Ashamed

बे-असर: Inefficacious

खुमार: Languor

क़र्ज़दार: Indebted

निसार: Sacrifice

दिल-इ मुज़्तरिब: Restless heart

आसार: Symptoms

ला-इलाज: Incurable

फ़िगार: Wounded

शाम-इ-वस्ल: Evening of union

मनीष: Pen-name

रुखसती: Departure

दीदार: Sight

***

Saans mein aate rahe saans mein tum jate rahe

Dil ki beqaraari dil mein barqaraar rahe

Kaun chahe ke tumhe dekh ke sharmsaar ho

Be-asar na ho nazar mein itna khumaar rahe

Hai qarzdaar kai jo subh-o-shaam aate hain

Waqt behisaab magar tum par nisaar rahe

Dil-e-muztarib mein khile jo aasaar thay

Ho haseen na sahi la-ilaaj figaar rahe

Yeh woh ghadi hai shaam-e-vasl ki manish

Rukhsati ke baad bhi jab tera deedar rahe

***

Beqarari: Restlessness

Barqarar: Continuous

Sharmsaar: Ashamed

Be-asar: Inefficacious

Khumaar: Languor

Qarzdar: Indebted

Nisaar: Sacrifice

Dil-e-Muztarib: Restless heart

Aasaar: Symptoms

La-ilaaj: Incurable

Figaar: Wounded

Shaam-e-vasl Evening of union

Manish: pen-name

Rukhsati: Departure

Deedar: Sight

***

March 3, 2019

Salma Agha: The Sultanat of Salma

Allah jaane kaun banega iss Salma ka Balma, she cried out on 4 March, 1986.

Dressed in a floral maxi gown, a tight auburn bun, with oval drops of thick yellow gold on her earlobes and adjusting her oversized obsidian dark glares, she walked past Rakhi Sawant at an electronics store in Lokhandwala.

She began to size-up the air conditioners on display. She bobbed her head up and down to make measurements in her head. Sawant walked up to her, patted her shoulder, pouted, and said, “Mera naam Shalma, tu bata?”

She didn’t twitch, her lips didn’t curl in surprise. She lowered her glares with a rehearsed stillness as in a stage performance. She looked at Sawant straight in the eye; her algae-green pupils expanding like ink drops on blotting paper, almost commandeering Sawant to run along in search of Kryptonite, a mythical substance that is illuminated by the light from her sweetheart cat-squint.

Her nasal chord opened to call Sawant’s bluff, “That’s not how you do it snowflake,” she said. Sawant nodded and said, “Ok, main dancshing, tu chal gaa.”

Someone handed her a dummy mike. The store blinked hot neon colours and transformed into an Eighties disco club; lights dimmed, drums rolled, and once again she in her silver sequinned butterfly top and cherry red lipstick pouted and sang, “Mera naam Salma…Salma…Salma…Allah jaane kaun banega iss Salma ka Balma.”

Salma Agha, Rakhi Sawant.

Salma Agha, Rakhi Sawant.When she sang the second line “Allah jaane kaun banega iss Salma ka Balma,” the sky tore up with a tearing sound like something was falling through.

Outside the mall policemen had to use laathis to keep the mob in place. Aliens had landed on the roof of the mall. They had heard her voice boom across the milky-milky way. Smooth as sour cream, that Salma was looking for her Balma.

Each one of the green men from outer space claimed to be her green-eyed Balma. They bobbed out of their vessel, making a strange yet coherent sound in union: Balma! Balma! Balma!

Salma Agha was not entirely convinced.

She would go with the one who could pronounce Balma the correct way; with the tongue hitting the roof of the mouth at bal and opening wide for ma. As Shakti Kapoor had learned to pronounce Bal-ma after he had heard her singing it in the film Aap Ke Saath, on 4 March, 1986. Playing the character of BAtuknath Lalanprasad MAalpani, he had pronounced his acrostic pet name Bal-ma in the film Chalbaaz in 1989. Sridevi had followed Shakti Kapoor’s lippy enunciation in Chalbaaz and thrashed the Bal-ma. Kapoor was too sore (and a bore) to be a suitor after that.

The doors were thrown open for a Balma call.

It was a herculean task for the aliens since they did not have tongues to please her.

The singing pigeons of Kabutarkhana were strangulated after they chorused off-key.

A python that had emerged from a water pipe in Tansa had its head squashed after it tried to woo Salma with a rather near-perfect sss-Salma hiss.

Shrew mice from Sion were shot down for anarchic chatter.

In-Humans of Mumbai and Rakhi Sawant’s lisping lips were not allowed to audition.

Her better half had to be someone super human, super alien, someone out of this galaxy.

‘Allah jaane kaun banega iss Salma ka Balma,’ the melody has punctured a hole in the solar system and was traveling faster than light.

https://medium.com/media/106a7707bb84c0e6d1e6e7e0c453e145/href

February 26, 2019

नज़्म/Nazm

Carl Heinrich Hoff

Carl Heinrich Hoffतुम्हारे खत ही बचे थे

मुझे ज़िंदा रखने के लिए

नज़्मों पर तुम्हारे

नीली बर्फ जमी थी

और सामने बुझते चराग में

मेरी साँसे थमी थी

तोह उठा कर तुम्हारे काग़ज़ी जज़्बों को

जला दिया पर बुझा न सकी आरज़ू

के फ़ज़ा में अलम बरक़रार रहे

वह ख़याल जिसे आक़िबत मंज़ूर नहीं

फ़ज़ा: मौसम, अलम: दुःख, आक़िबत: अंत

…

Tumhare khat hi bache thay

Mujhe zinda rakhne ke liye

Nazmon par tumhare

Neeli barf jami thi

Aur saamne bujhte chiraag mein

Meri saanse thami thi

Toh utha kar tumhare kaagazi jazbon ko

Jala diya phir bujha na saki arzoo

Ke fazaa mein alam barqaraar rahe

Woh khayal jisse aaqibat manzoor nahi

Fazaa: Ambience, Alam: Grief, Aaqibat: Conclusion

…

Your letters alone have survived

To keep me alive

Blue ice has blanketed

Your poems

And in the dying embers before me

My last breath flickers

I burn your papery emotions

That cannot contain my desire

A grieving scent permeates the air

Resisting its turn for conclusion

February 24, 2019

A R Rahman: The Faking of Mozart

What he said and what he left unsaid in his Oscar acceptance speech

Rahman called up long time collaborator lyricist Mehboob, and said, ‘Listen man, I need to dedicate a song to amma. It’s long overdue. Even the vadas are getting soggy bottom at lunch. You need to help me on this one macha.’ Mehboob followed the conversation with a nod.

Back at home, Kareema Begum was watching television, when a video from the film Indian distracted her, The song was, ‘Telephone dhun mein hasne waali, Melbourne macchli machalne waali.’ She clicked her tongue in distaste.

‘Enna da,’ she blurted to a heavily pregnant Saira, ‘What is this fish talking business, I hope he is not inspired by your giggling in the house.’ Saira couldn’t care what mother-in-law thought, she knew if she tried to crack a smile her belly would try to breathe as well, and she did not have any more room for elasticity. Her humour was in short supply at the moment.

‘My son needs rest, look at the filth he is churning out these days, this is not music, fish curry.’ Kareema fumed. ‘Amma,’ Saira acknowledged, ‘You should tell him to stop.’ Kareema, satisfied that Saira understood what she meant, fussed further on her way to the kitchen where the pressure cooker had whistled for her attention. She came back to Saira with a quarter plate of thinly sliced unripe mangoes sprinkled with malaga podi, ‘Here you go, you need some indulgence.’

Rahman was caught in a rut. It had been five years since Roja and he was taking on all of the projects that came his way, churning mediocrity in the name of music. None were pleased, least of all Rahman himself who knew that if he delivered one hit in the name of his mother, he would be back on track. He stared at his mother’s smiling portrait hung in his recording room.

At an awards show Rahman met Bharat Bala and confessed his need for a bail-out. It was perfect timing. Bala asked him to re-jig Vande Mataram as India’s 50 years of Independence was close and it would befit both the nation and his mother.

In January 1997, on the 27th day of Ramzan, Rahman, who has a notorious reputation for working in the wee hours, descended into his musical lair built under the now deserted street at Kodambakkam.

Rahman believed that at 2am, when he composed the first two verses of Maa Tujhe Salaam, angels had opened the gates of heaven and a cosmic light had filtered into his studio and answered his prayers. His mother’s portrait shone in the divine light. Mehboob wrote additional words, Bala conceived a music video on a mammoth scale and Sony Music was quick to herald the music sensation of Asia.

Kareema Begum with Rahman.

Kareema Begum with Rahman.During the filming of the video, Rahman suggested to Bala that in order to give a thrust to the tempo of the song, he would stomp his feet in defiant declaration when the phrase ‘ma ma tujhe salaam’ came about in the lyrics. Bala thought it didn’t go with the fluid style of the video but gave in. When the part came where Rahman screeches ‘ma ma tujhe salaam,’ he head-banged his curly locks, stomped like a mini-stallion, and threw up his short arms like a manic circus clown. Bala was convinced of Rahman’s superlative acting skills. The shot was canned in one take.

Saira had been bribed by Rahman to tell Amma that what Rahman was actually singing in the video was ‘amma tujhe salaam’ after the phrase ‘ma ma tujhe salaam’ was repeated. Rahman thought Saira’s word would do the trick.

Kareema, who was beginning to get tone deaf, not particularly due to her son’s cacophonic music, didn’t really buy the con each time the video played on television when Saira would tug at her Chettinad saree tucked in the traditional pinkosu style and tell her how her son had jubilantly included ‘amma’ in the national song to pay tribute to her. ‘What cheek, comparing me to mother India!’ Kareema would chuckle back to her chores, careful to not reveal too much of her unbridled joy.

Such was the impact of the Vande Mataram album that Rahman was flooded with work from as far as Japan and Finland and with his inspiration Michael Jackson. There was no looking back since, not even for mother’s advice.

Twelve years later at the Oscars ceremony, when Rahman was tongue-tied receiving his trophies, the best he could come up with in his acceptance speech was ‘Mere paas Maa hai.’

Saira clucked, “He should have said, Mere paas Amma hai.”

The world was watching.

Kareema, draped in a lustrous red and gold Kanjeevaram, sitting in the audience with Saira, nudged her and smiled, ‘Oh, my favourite child.’

Both mother and son had reached an impasse. It was time to hug and turn around.

https://medium.com/media/4e5df8235ea53350202b96f51e8c83d7/href

February 16, 2019

POEM: Pulwama, what’s ❤ got to do with it?

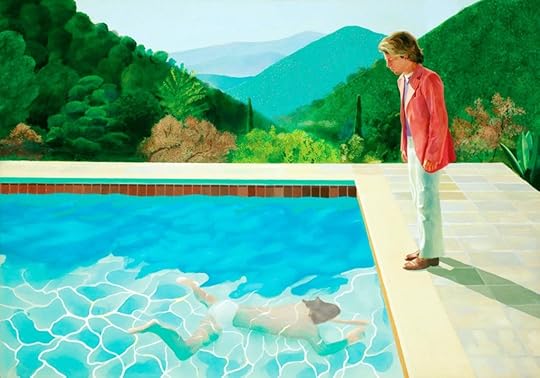

Pool With Two Figures — David Hockney

Pool With Two Figures — David HockneyOn Saint Valentine’s Day

When we were all a little poor for love

Adil, a fidayeen, bombed his broken heart

To reach a place he had booked in heaven

My friend Dil, a soldier

Looked around him in Pulwama and wondered

अगर फ़िरदौस बर-रू-ए-ज़मीं अस्त (If there is a paradise on earth)

What fresh hell is this?

Adil and Dil, two hearts asunder

With only a heartbeat in common

February 15, 2019

Bangalore Poem: 9PM

Yeh sheher so gaya

Raahein ruk gayi

Chalte chalte kahin

Manzilein mit gayi

Kahan gaye musafir

Parchaiyaan chhup gayi

Veeran hai manzar

Ghubaar hai basti

Yaadon ka lamba safar

Kis qadar hoga basar

Soona hai yeh caravan

Saraab hai humsafar

Dard ke sholon par

Bhar aaye abr aasmaani

Kadmon se bujh rahi hai

Khwabon ki rangeen ravani

Aadmi ko nahi

Aadmi ki khabar

Aise gard mausam mein

Insaan mukhtasar

February 8, 2019

Stateless Poem: The Ghost In The Washing Machine

The Sock Knitter, Grace Cossington Smith

The Sock Knitter, Grace Cossington Smiththe washing machine gobbled up a sock

and if i walk around with a limp

will the world not be kinder?

.

the machine never eats in pairs

spitting no unchewable threads

recycling from the other side

where there are no mistakes

.

to vanish without a trace

is as forgettable

as staying behind

out of ordinariness

.

the sock in a vacuum is to hólon

that never leaving is cherished after death

…

February 7, 2019

Delhi Poem

Man With A Bouquet Of Flowers — Bhupen Khakhar

Man With A Bouquet Of Flowers — Bhupen KhakharKai baar jamunaa paar kiya

Bhulaane ke liye tumhe yaad kiya

Kai baar jamunaa paar kiya

Khud se mulaqat ka israar kiya

…