Manish Gaekwad's Blog, page 3

March 15, 2021

Arati Mukherjee: How She Sang The Song That Makes Us Cry

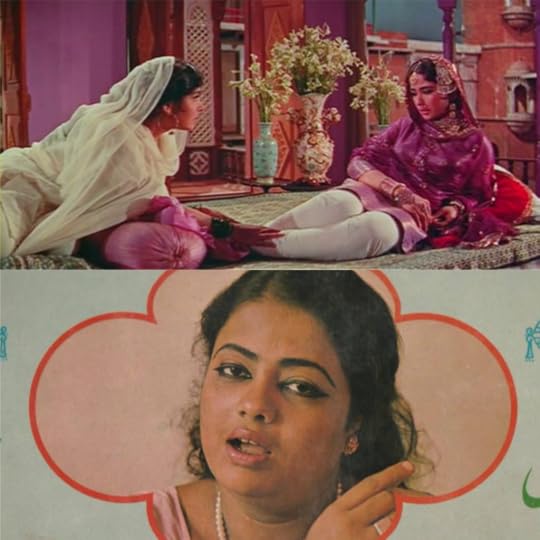

Do Naina Aur Ek Kahani in Masoom.

In 1983, when Shekhar Kapur was filming Masoom, he asked music composer RD Burman for a melancholic melody.

‘It should make people cry. Paani, paani aana chahiye aankh mein,’ he said.

‘Itne budget mein tum mera paani toh nikal ke hi rahoge,’ Burman replied.

‘Oh dada, you fuss too much’ Kapur said. ‘You will get a Filmfare award.’

‘Haan, why not, lagey haath kisi singer ko bhi award dila dete hain,’ Burman said.

‘Who?’

‘Asha!’

‘No, we can’t afford her.’

‘Phir?’

‘Get someone from Calcutta dada. You know those Rabindrasangeet- classical types. They deliver in one take. They have years of practise singing like a cuckoo from a willowy tree, and they will do it free for you.’

‘Hmn, dono aankh mein ek kahani, thoda uska badal, thoda hamara paani,’ Burman said.

‘Exactly, you know how to milk music dada,’ Kapur said.

Burman called Arati Mukherjee. She was the go-to voice for playback in Bengali films.

‘Arati, ek art film hai, paisa…’ Burman coughed on the phone.

‘Dada, aap ke paas kabhi bola kya yeh sab,’ Arati replied in a language she rarely spoke. ‘Hum toh kabhi yeh sab naam hi nahi lete hai paise ki.’

Burman was relieved that Arati was not negotiating money.

When she read lyricist Gulzar’s words in the recording studio, she wept like a child who could not recollect what she was crying for.

Chhoti si do jheelon mein woh behti rehti hai

Koi sune yaa naa sune kehti rehti hai

Kuch likh ke aur kuch zubani

In two small streams she flows

She speaks regardless of being heard

Some in words, some orally

‘Kya hua?’ Burman asked.

‘Bachpan yaad aa gaya,’ she cleared her throat and tried to push back her tears.

‘Paani,’ Kapur said, offering her a glass of water. Paani, his operative word.

Arati looked at Gulzar and sighed after drinking the water. She read the lyrics further.

Thodi si hai jaani hui thodi si nayi

Jahan ruke aansoo wahin poori ho gayi

Hai toh nai phir bhi hai purani

A little is familiar, a little new

When tears stop to complete

What seems new is known too

The simple and profound lyrics were rekindling some buried memories in her. Arati was feeling the return of an innocent time. Before she became an established playback singer, she used to sing for herself. That had stopped in films. She always had to picture who would be singing it on-screen. It felt different with these lyrics. She stepped into the recording booth and sang.

She was singing about the feelings of tears and tearing up feeling it.

Do Naina Aur Ek Kahani was recorded in one take.

Arati came out and asked Burman if she was good.

‘Ho gaya?’ she asked.

‘Haan,’ he said.

‘Itni jaldi?’

‘Haan, tum toh perfect gaya,’ he said. ‘Itna mat ro, paisa bhi milega aur award bhi.’

He made her laugh.

She returned home happy and light, a sense of purpose one gets after a good cry.

A year later, both Burman and Arati won the Filmfare award for the composition.

Burman called Arati and said, ‘Kya, abhi bishwas hua ki nahi, ke main sach bolta hoon.”

Arati recalled that evening. She remembered that special day when all the musicians in the studio congratulated her and said she is crying now but she will be happy when she wins the best playback singer trophy.

Ek khatm ho toh doosari raat aa jaati hai

Hothhon pe phir bhooli hui baat aa jaati hai

As one ends, another night returns

The forgotten word on my lips torment

Thoda sa baadal thoda sa paani

Aur ek kahani

Do naina aur ek kahani

A small cloud, a teardrop of water

And a story

Two eyes and a story

‘Mujhe toh kabhi bishwas hi nahi hota hai,’ Arati cried out laughing.

https://medium.com/media/de2b7283ddecb96e4befff4781bbee8d/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

March 13, 2021

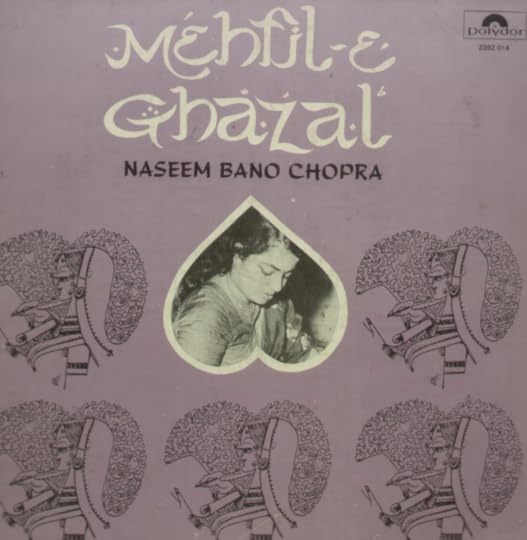

Naseem Bano: Who Shall I Sing For?

Side-tracked to a railroad ghazal in the background score of Pakeezah

Dilip saab aayenge, said a frail Naseem Bano Chopra to the nurse on night duty in Bandra’s Guru Nanak Hospital.

Haan, we are also waiting for Yusuf uncle kab se, said the nurse. I pray to Jesus unko phir kabhi yahan ka rasta mat dikhao. (God forbid him ever to come here again).

She smiled and tucked Chopra to sleep.

Chopra had begun muttering after days of rest.

She was found in a paralysed state and admitted to a hospital by her neighbours. A grubby man, who claimed to be her attendant, showed people the tattered jacket of an LP Buzm-E-Ghazal to collect funds for her treatment.

https://medium.com/media/1b1002f4e199344ab6d2d015846e4150/hrefChopra had sung for the music composer Naushad. Her claim to Hindi films was the song Dekh Toh Dil Ke Jaan Se Uthta Hai, a ghazal written by Mir Taqi Mir, and used in the background in Pakeezah when Meena Kumari talks about love and its distant, fading call.

Chopra’s clear voice rises like a sadaa, an echo reverberating Meena’s yet unspoken desire.

dekh to dil ki jaañ se uThtā hai

ye dhuāñ sā kahāñ se uThtā hai

From the heart or the breath

Where does this fog rise from?

Chopra was a famous singer back in the day when artists visited the kotha district in Bombay. And just like that, she slipped into obscurity when the culture languished.

Chopra began to speak clearly to the nurse.

Har raat teen baje ek rail gaadi apni patriyon se utar kar mere dil se guzarti hai aur mujhe ek paigham de jaati hai. (Every night at three a train derails and passes through my heart, leaving a message for me)

The nurse was surprised to hear her form a long sentence. She congratulated Chopra.

Arre wah, tum toh theek ho gayi. Accha hai, kal chhutthi kar sakte hain. (You have recovered. Tomorrow you can go home)

Saying so, the nurse got up.

Chopra’s hand moved. She gestured the nurse. The nurse lowered her head to hear Chopra.

Train aa gayi hai, said Chopra.

The sound of a Bandra fast local was familiar to everyone in the room, even when it was not passing by at this quiet hour. It seemed wistful of Chopra to talk about trains in her current state, the nurse thought.

The nurse caressed her head and left.

At three in the morning, Chopra opened her eyes. She helplessly stared at the milky white ceiling in the dark, as one stares at the opacity of heaven. The train was on time. She could see her soul, a liquid white flame, floating up from her body to travel into another realm.

gor kis diljale kī hai ye falak

shola ik sub.h yaañ se uThtā hai

Which broken-hearted’s tomb the sky ishttps://medium.com/media/1475d056f6f8604d987095b2c345846c/href

A morning flame rises from the earth

Disclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

October 29, 2020

Invitation to a Beheading

A bullet for a doodle?

Image: The New Yorker

Image: The New Yorker‘We must retaliate,’ said the chief.

The armed, masked men around him, raised their Kalashnikovs in the air, taking their god’s name in greatness.

‘Drop your guns, you fools,’ he said, ‘it does not stop them. They multiply.’

‘What do you mean?’ said one scowling rebel, ‘we will kill them all.’

‘That is exactly what they want, don’t you see?’ the chief bowed his head in despair.

‘An eye for an eye balances the world, but a bullet for a doodle, that’s a bit unfair, don’t you think?’

‘So you mean we should sketch on paper now, instead of waging a war?’ asked a follower of the great faith.

‘What do you suggest my friend?’ said the chief. ‘Which is easier done? Guns or cartoons?’

‘Guns,’ said one, ‘we don’t know how to make cartoons.’

‘That is what is missing,’ said the chief. ‘Humour, you people are too blinded by faith.’

The men looked puzzled, trying to understand what the chief meant by insulting them.

Silence followed to the count of three.

They riddled the chief’s body with bullets.

‘Idiot,’ a rebel laughed, severing the chief’s bloodied head with a knife. ‘Those cartoons look quite funny, poor man, could never explain what is written in it.’

The rebel kicked the chief’s head. It rolled and rolled and rolled. Like a ball of fire in a cartoon.

September 19, 2020

September 17, 2020

Meena Kumari: A Poetess Without An Audience

‘Main Shayara Hoon!’

If it had ever occurred to Mahjabeen (her real name) that she would have to time-travel to be heard, she would have done it sooner than later.

Sooner than later?

What a vexing conundrum, she thought, assaulting a spittoon with a gob of chewed paan.

Nirmala, her maid, was sitting on the floor, tidying clothes.

Mahjabeen was coughing her last phlegm, anticipating death to be closer than farther. Another vexation.

It had been three weeks since the release of Pakeezah. The film had been long in the making, mainly due to acrimony with her producer-director husband Kamal Amrohi, and her deteriorating health caused by chronic alcoholism.

In between, she had been to London for treatment. She had been diagnosed with cirrhosis. Her liver had shrunk. One of the symptoms of the illness was the depression that came along with fame.

Doctor Sheila Sherlock had cured her. It took no less than a detective’s namesake to reach the root cause and put a stopper on the bottle. After she had returned to Bombay, she had abstained from drinking.

Mahjabeen also suffered from acute lovelessness. The nights were too long in waiting.

Pakeezah’s lukewarm reception aggravated her symptoms. Was there no one to love Sahib Jaan?

She relapsed. It was her thirst for alcohol mixed with her loneliness that began to play with her mind. She became delirious.

Nirmala, intrigued by the strange translucent windsock lying on the floor mat, said, ‘Aapa, this jaraab, it’s not even your size.’

Mahjabeen tailed her malignant cough with laughter. ‘Pagli, blow it first. It’s the kafan I ordered from Mecca.’’

Nirmala’s eyes widened. She adjusted her dupatta over her head, sanctimonious at once, ‘I don’t have so much air in me.’

Mahjabeen grew irascible, ‘You’re full of gas, do it fast now.’

The girl sat upright on the mat, bunched the fabric and held the wide mouth of the windsock close to her lips and blew a short burst of air into its deflated glassy lung. The windsock lit up into a dull white light. Nirmala felt the windsock rising from her fingers.

‘This is flying,’ she cried.

‘Oh hurry up, hold it silly girl,’ Mahjabeen scolded her, ‘I don’t have much time, stop playing with it, it’s my burial bag.’

Mahjabeen took ill the same night and was taken to St Elizabeth’s Nursing Home. For two days she complained of a dry throat that water could not quench.

On the third day, she went into coma in her sleep.

Three days later, Nirmala was staring at Mahjabeen aapa, who was stuffed in the big sock, its mouth tied with a cheery red ribbon. The pale woman looked like puffed, day-old pastry wrapped in a diaphanous cellophane shroud. Nirmala had seen something similar once at a confectionary store in Colaba. It looked expensive and stale as jaundice yellow.

The fresh sweets were at the local halwai in Mahim where Nirmala went to buy curd and milk. The halwai let her pick the sticky murabba and press it between her thumb and forefinger. A treacly liquid rose up through its translucent centre, surging her greed.

‘Give me this one,’ she grinned at him, sinking her teeth into the spongy sweet as she walked out with her day’s purchase.

Mahjabeen was that kind of sweet. Crusty on the outside, but gooey from within.

Her body was brought to her eleventh floor apartment in the Landmark building. Her sister Madhu gave her a bath. Her friends flocked for a final glimpse as she lay in her bed for deedar.

In the evening, her mourners began chanting La Illaha IllAllah and carried her body on their shoulders. Ministers, actors, relatives, many, men took turns as pallbearers to hold the coffin as it grew heavier with grief.

On her way out, a neighbour played a song from Pakeezah.

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha sar reh rah chalte chaltehttps://medium.com/media/9d4a10cb0af830618c4784d7a9e86f5a/href

Wahin tham ke reh gayi hai meri raat dhalte dhalte

Mahjabeen was laid in an enamelled coffin and lowered into the earth.

Dharmendra arrived at the cemetery, placing a white handkerchief on his head and raising his hand up, saying, ‘Allah, forgive the deceased her sins and grant her eternal peace in heaven.’

Mahjabeen’s ears would have rebelled against those very words. She had not sinned alone, if this was her punishment for a crime: her paramour reading her faatihaa.

Kamal Amrohi wanted to bury her in his village in Amroha. Here, she lay in Mazagaon. He held a fistful of dust and tossed it in the pit where her coffin was laid.

Her epitaph read:

Rah dekha karenge sadiyon tak

Hum chale jayenge jahan tanha

You will wait an eternity for me

Where I will now walk in solitude

‘From dust to eternity indeed,’ Kamal said.

An hour before midnight, her grave was covered in warm soil. Nirmala hoped Mahjabeen would melt from the heat inside the shiny bag and disappear as she had told Nirmala before she died.

‘I will not go into an afterlife. I defy faith. I will be back. In this life, in all of my wretched existence, no one paid attention to my fariyaad. I could not be a poetess. What then did I become, haan?’ Mahjabeen had ranted a few days ago.

Nirmala had sat silently, listening to her tirade. Nirmala had found her very becoming of a maharani and had nicknamed her so.

Mahjabeen’s career as an actress was long over. She was bloating and gloating. She wished to start another, as a poet in the stature of Mir, Firaq and Ghalib. Everyone had laughed at her. Some were even appalled at her temerity.

They liked her talking in the talkies, her ‘loony-moony’ voice full of sorrow, but when she began with her poems, they loved her even more. They roared with applause and filled her glass with cheap whiskey. Men who roamed the streets at night came in droves, the regular rascals Mahjabeen had befriended one evening, shouting from the ivoried balcony as her pallu slipped, baring her ample bosom to an unsuspecting crowd, ‘Poochte ho toh sunoh kaise basar hoti hai?’

Someone had yelled back ‘kaise?’

That’s how her new endeavour began.

A bunch of hooligans, Nirmala thought, milling at Mahjabeen’s doorstep every night in search of daaru and chalu shayari.

Poochte ho toh sunoh kaise basar hoti hai

Raat khairat ki, sadqe ki sehar hoti hai

Saans bharne ko toh jeena nahi kehte ya rab

Dil bhi dukhta hai na, ab aasteen tar hoti hai

Jaise jaage huye aankhon mein chubhe kaanch ke khwab

Raat iss tarah diwaanon ki basar hoti hai

Gham hi dushman hai mera gham hi koi dil dhundta hai

Ek lamhe ki judaai bhi agar hoti hai

Ek markaz ki talaash, ek bhatakti khusboo

Kabhi manzil kabhi tamhid-e-safar hoti hai

Poochte ho toh sunoh kaise basar hoti hai

Raat khairat ki, sadqe ki sehar hoti hai

***

Listen if you are asking about my woeful existence

The night goes by charity, as alms comes morning

Breathing alone is not called living oh lord

The heart cries and the sleeves are wet

Open eyes are pierced by the shard of dreams

This is how the night of the mad lovers is spent

Sorrow is the enemy my heart seeks

If even for a moment it abandons me

In search of a centre, a wandering fragrance

Sometimes finds a destination, sometimes a journey

Listen if you are asking about my woeful existencehttps://medium.com/media/d4fff061999194869358c6fda3eee354/href

The night goes by charity, as alms comes morning

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, business, events and incidents are the products of the author’s overactive imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely a reflection of form.

September 11, 2020

The Falling Man

Who fell from the sky on September 11.

RICHARD DREW/AP

RICHARD DREW/APStanding on his balcony, I recollect looking at the picture of The Falling Man in the Times of India.

People discussing the photograph, looked pained, commenting mostly at their tragic loss of words to speak commemoratively of the man.

Like pouting vultures we stood on higher ground, moistening eyes with pity; for us not to swoop on this defeat of the human spirit as we gazed into the image placated on the table in front of us — his paper grave.

I made a mistake I will never quite forget every time I come across the image again. In that minute of condolence we held in the boardroom, I turned the page upside down, and said, “Why don’t you people look at it like this?”

A collective gasp rose up, like an uncertain cloud over the falling man’s head, waiting for a thunderbolt to strike him down.

“He isn’t going down; he’s actually shooting up like a free bird.”

As clowns vertically digested to throw up through cannon pits know that men can fly without wings, the falling man chose to do the same instead of melting like wax in the tower of an inferno.

Some people in the room immediately decided to distance themselves from me. “Weirdo”, they thought, ready to set fire to the canon whistle in which I was now roped and balled to flame up.

Gwendolyn, 9/11: The Falling Man: “I hope we’re not trying to figure out who he is and more figure out who we are through watching that.”

Excerpt from Lean Days (HarperCollinsIndia)

September 7, 2020

Begum Akhtar: The Saddest Ghazal Singer In The World

When her twin sister Zohra died, depression became her earliest solace.

Begum Akhtar’s twin sister Zohra died when she was four-years old.

Her estranged father’s family fed poisoned balushahis to the two sisters. They were rushed to a hospital in an unconscious state. When Bibbi, as Akhtar was called at home, woke up, she could not find Zohra.

‘Ammi, Zohra kahan hai?’(Mother, where is Zohra?) she asked her mother, Mushtari Bai.

‘Woh Allah ke ghar gayi hai,’ (She has gone to god’s house), Mushtari said, pointing heavenwards.

She gave Bibbi a white rumaal. ‘Zohra ka hai. Isse sambhal ke rakhna. Woh jab wapas aayegi, usse de dena,’ (This is Zohra’s. Keep it safe. She will need it when she returns)

Bibbi took the handkerchief begrudgingly. She could not understand what happened. She missed sitting on Zohra’s back, riding her like a horse and screaming aloud. The absence of her sister made Bibbi a quiet child. Depression became Bibbi’s earliest solace.

Her mother enrolled her in singing classes to make her speak.

Bibbi’s taleem (training) was tinged with sadness. She would keep Zohra’s handkerchief next to her and hold on to it when the riyaz (practise) got tough. Her voice soared into a wail. Mushtari did not stop Bibbi’s heart from crying. Melancholy was opening her vocal chords.

Soon Bibbi was performing in mehfils and on stage in bit roles as an actor. Her stage career was stalled after a king from a city in Bihar raped her. She was only a girl when she became an unwed mother. To shield Bibbi from shame, Mushtari told everyone that she had given birth to the newest member in the family. A girl they named Shamima.

‘Tum sab ko kehna yeh tumhari behen hai, theek hai?’ (You have to tell people she is your sister, alright?), Mushtari said.

Bibbi nodded her head. She thought her sister Zohra had returned as Shamima, but Mushtari made sure to keep them emotionally apart. It was not good news for Bibbi’s future to be attached to the newborn just when her career was on the rise.

Mushtari veered Bibbi towards cinema. Bibbi acted in films to accelerate her singing career but it did not take off. Music composers said her dolorous voice was suited for funerals.

One day, her mother took her to meet a pir (saint).

‘Iski kismet saath nahi de rahi, kuch kariye Pir saab,’ (Her luck seems to have run out, do something pir saab) said Mushtari.

‘Log kehte hain yeh sirf allah ke pyare ke liye gaati hai.’ (People say she sings only for the dead)

The pir asked Bibbi to show him her notebook of songs. She did as told. He asked her to open it to a page. She did. He pointed to a ghazal written on the page.

‘Yeh wali gao’ (Sing this one), he said.

It was a ghazal written by the poet Behzad Lakhnavi. It happened to be her favourite for riyaz. Bibbi sang the ghazal with a piercing urgency in mehfils, concerts, on radio, and had it recorded on disc.

In a mehfil, her mother could not help notice that the ghazal was making the men swoon.

‘Haye, gade murde bhi jag jaate hain,’ (Even the dead rise up) Mukhtari said, cracking her knuckles on her own head to bestow blessings on her gifted daughter.

Bibbi sang with her sister Zohra’s handkerchief seated beside her. It gave her confidence.

At thirty-one, when she married late, her barrister husband’s aristocratic lineage constrained her singing, where women from good families did not indulge in cheap entertainment.

Years passed in domesticity. She often began falling ill and had six miscarriages. She kept to herself, murmuring and humming songs. The doctors advised her to return to singing as the only remedy but she needed her husband’s approval.

He said she should have done it years ago instead of trying to fit into the role of a housewife.

‘Aaj se tum azaad raho,’ (Live freely from today), he said, unfettering her from the burden of marital duties.

Singing a khayal, a dadra, a ghazal on All India Radio felt like the mike was an apparatus resuscitating her with good health.

She wept at the end of the recording, clutching strongly Zohra’s handkerchief as if it was her sister’s hand. She sniffled, wiping her nose with the same handkerchief as a source of relief.

Some years later, filmmaker Satyajit Ray met her for a thumri in his film Jalsaghar (The Music Room).

‘Main Bengali mein bhi gaa sakti hoon,’ (I can sing in Bengali), Bibbi said.

She began to hum the tune of Jochona Koreche Aari.

https://medium.com/media/a4774953f88dafbb78d741028464df62/href‘No, no, I don’t want any popular song,’ Ray said.

‘The situation in the film is a janeu ceremony. It demands a festive song but I want something imbued with grief. It needs to be beautiful but ironic, joyous but tearful.’

Bibbi was hoping to sing a popular thumri. She mentioned Piya Nahi Aaye, Jab Se Shyam Sidhare, Na Ja Balam Pardes, but Ray would have none of it.

‘No, no, no,’ he said. ‘Which is your least-known thumri?’

‘Sab,’ (All of them) she said.

She preferred singing ghazals as it allowed her to mould her one-octave range without straining her pitch.

At a studio in Calcutta, a regal crystal chandelier was lit with yellow candles. It shimmered in the wall-length mirror across the red-carpeted room. The room with tall round pillars was fumigated with the sweet-vanilla lobaan scent.

Bibbi, wearing a pearl headband, a red bindi, chainmail earrings, an emerald-encrusted necklace, bangles, and her dazzling diamond nosepin, wrapped her head in her maroon Banarasi saree’s gold-border pallu. She strummed the tanpura, sitting along side her musicians on the tabla and the harmonium.

She exuded the decadence of zamindaari (feudal landowner)patronage without frills and concerned only with her star presence amongst keen listeners.

https://medium.com/media/423af1924fb20f50901056551423cf20/hrefAs she sang Bhar Bhar Aayi Mori Akhiyan, she noticed an actor was instructed to snort tobacco and use a handkerchief for relief. Watching him, she realised Zohra was missing; her handkerchief companion was absent from this music room.

Bibbi was so uninspired to perform that she had forgotten to carry the handkerchief. What could Bibbi do now? Could Zohra’s absence deepen the melancholy required for the rendition?

She requested for another take.

When she saw the man dab his mouth again, she thought of it as a sign to let go of Zohra. Could she ever not be without her twin?

Bhar bhar aayi mori akhiyan, she applied the khatka and the taan but nothing seemed to bring tears to her dry eyes. She sang the thumri in a state of trance; one where she was floating in dispassionately.

After the performance, there was no applause. The director had not included it in the scene. With Zohra not beside her, with no appreciation for her performance, she felt out of place. Something was amiss, even cold, but she was in a daze to register its chilling intensity. The experience numbly darkened the colour of her existential sorrow.

She decided never to appear on film again. Jalsaghar was released and did not make a noise. It made no difference to her fame.

Many years later, while performing at a concert in Kerala, she raised her pitch and felt a tear in her voice. It had begun to crack. She coughed into Zohra’s handkerchief and noticed red spots of blood. Sadness had an undeniable bright hue.

She was dying of excess. Drinking, smoking, loneliness, and the demands of the job, she was using all of it to obliterate the pain she felt within. It crystallised in her radiant, heart-wrenching voice.

Ray, who had always heard her on disc and never in a mehfil, walked into a private mehfil in Ahmedabad where Bibbi was performing. She had just finished singing a ghazal written by poet Shakeel Badayuni.

mere ham-nafas mere ham-navā mujhe dost ban ke daġhā na de

maiñ huuñ dard-e-ishq se jāñ-ba-lab mujhe zindagī kī duā na de

My friend, my companion, do not deceive me in your companyhttps://medium.com/media/3f6805566b9352588cd01f522f505bc3/href

I am already wounded in love, do not give me the hope of life

Spotting him, she coughed, cleared her wheezy chest and said, ‘Aur yeh ek aakhri ghazal pesh hai ek khaas dost ke liye, jinka jab bhi zikr hoga, reham se hamey bhi yaad kiya jaayega.’ (And this last ghazal is for a special friend, who when remembered, will also remind you of me.)

As she sang the first couplet, the music room roared with cries of wah-wah and claps.

dīvāna banānā hai to dīvāna banā de

varna kahīñ taqdīr tamāsha na banā de

Make me sound crazy if you want to

Or fate will make a show out of me

Ray was stunned by the reception. He had downplayed it in the film. This was the response Bibbi was used to. It replenished the vigour in the throw of her fading voice. This was the ghazal she had turned the page to in her book of lyrics. The ghazal the pir said would immortalise her.

Bibbi sang full-throated for one last time. Zohra’s handkerchief sat beside her.

Four days after the mehfil, Bibbi dreamt she was with her twin sister in heaven.

https://medium.com/media/6126d797a05368f777a1b6856df57965/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

August 27, 2020

How My Closeted Aunt Helped Me Embrace My Sexuality

She saw in me what she was unable to express in herself.

Portrait of Aunt Pepa by Pablo Picasso.

Portrait of Aunt Pepa by Pablo Picasso.(An edited version of this essay first appeared in Arre)

In August 2017, when the Supreme Court in Delhi was decriminalising portions of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code that stigmatised queer lives, my maternal aunt was in Pune, comatose.

I joked that the news must have reached her. Like how people go into a food coma after a gustatory orgy, she must have gone delirious with happiness and passed out. Alas! She sighed and breathed her last. Liberated in the knowledge that there could have been an alternate life to live, a gayer one.

She could not have been gay in this life. She was not allowed to despite some very obvious signs.

She had what they called a manly gait, a deep voice more masculine than feminine (her larynx tremoured less), and a golden moustache to match a sarpanch’s brittle whiskers in the Kanjar community where she often spoke out loud for women’s rights. She had the hauteur of a warlord.

Her physical attributes also fit the butch stereotype when I met her for the first time. I was nineteen, what better did I know than to pigeonhole my aunt as a queer sort. She was so intimidating on sight that I could only think of her as no less than a man but also more of a clichéd man-hating lesbian — the kind Bollywood detested by projecting as an aberrant to society.

My aunt had what they also called, the rotten morals of an uncivil man. She had never been to school, despised marriage, was separated from her spouse, did not have children, and lived well into her fifties, drinking, smoking, gambling, and, once in a while, seeing random drunk boyfriends she cared even less for.

She was everything I admired in a woman — the kind of outspokenness that made her a champion for those who could not find their own voice. But it also removed her for the intimacy of affection from those who respected her from a distance. People feared her rejection even after appearing servile before her. She held sway, but real love evaded her.

In her, I could see the struggle of queer folx trying to fit in a world where one is raised binary. It reflected the anxiety of the queer folx to come out to their parents or to suffocate in fear because they have been raised to believe that being different is being dirty, vile, and shameful. A cursory look around her environment was enough to cement that perception.

Everyone around her called her gaandi (mad) in the Kanjar dialect. Did my aunt conform to any fixed gender binary? Certainly not. She lived and perished without ever finding out where she stood in the spectrum. Could she have known better if the queer community had been given equal rights and if Section 377 was abolished when the Constitution was formed?

I was nineteen when my mother was scouting for a young girl to fix my engagement. We were being served tea by a chit of a girl in a shanty on the outskirts of Pune. It was bewildering. I stood outside the house, wondering what to make of this all-too-real insanity. Mother said the Kanjar community would take us back into its antiquated folds. I disapproved of mother’s ideas but who did I have to seek counsel? Who would listen to my unspeakable thoughts?

That is when my aunt stepped in.

She gave my mother a verbal lashing. “Can’t you see how naazuk (delicate) your son is?” she railed in a mock tone, perhaps conversely hinting at my fledgling queerness and giving me a rather strong vibe that she understood. It needn’t have been said explicitly, but a little understanding goes a long way in being accepted.

Naazuk she said, defining that age when one is beginning to metamorphose from teenage to adulthood. I was not a man, but a boy in a confused state. She understood that I was different, just like her. She had only just met me recently, and had observed me in those few months that I lived in her house in the slum. I didn’t show any obvious signs of being queer, but my interest in books, my low voice, my general demeanour as a non-aggressive person was at odds with the active boys in the compound. She reckoned that there was more to my sensitive nature than just these physical attributes.

My mother had to heed her elder sister’s advice. She temporarily stalled her hunt for a suitable bride, but she did not pick up the other clue. The delicateness of the matter went unobserved, or as most mothers, she pretended to look the other way. There is no mother in the world that does not know what her child is up to, but she will not acknowledge it because her worst fears will come true if she admits it. My mother was hoping against hope that her son would turn out fine once the androgynous phase of teenage hood was past. I say androgynous not in the context of gender-bending, but what parents think is a experimental phase for their children to come into their own by choosing the acceptable binary.

‘Yeh toh umar hi aisi hai, behek jaate hain bacche, umar ke saath sudhar jayenge,’ (This is an age-related confusion, they will improve with age.) Families reconcile themselves.

Queer folx who struggle to come out to their parents live in fear because they have been raised to believe that being non-binary is being dirty, vile, and shameful. That the kids are besmirching the family’s name with sinful acts of carnality, if they so much as even express any queer feelings. In the toxic environment where parents raise their young, “normal” has a fine “formal” ring to it. Different is “abnormal”, or only the abnormal is different — both ways it’s a tightrope to dispel queer phobia.

The shame, that otherness, which queer folx fight on a daily basis, will not change overnight. I got a taste of that right away when after the announcement of the verdict I heard from relatives that the gaandi aunt had died. I wanted to celebrate the verdict, but I had to pause, to bereave someone I did not know enough, who perhaps also did not get a chance to know herself enough.

What did I feel for my aunt? Nothing. She died in ignorance of choosing a better life for herself. She must have been indirectly aware of the fluidity of identity in a slum inhabited by all kinds of ghettoised minorities, and maybe that was why her apparent unfeminine-ness was her way of channelling her rebellion in some measure, if not entirely being able to assert it for the fear of being ostracised.

Not for herself, but for others, she voiced her concern. What my aunt did for me at nineteen was something she could not have probably done for her own self at nineteen. Is a woman ever really in her prime in her teens? And when she came of age, was it too late? That day, when she rebuked my mother, and when she spun my concupiscence in delicate fibre, she cut loose the rhythm of silence, of suffering — passing on the baton of time. I will speak up when I am ready, just as she once did. It is never too late to reclaim oneself from others. Her death returns hope.

I now think of my aunt like Josefa Ruiz Blasco, the aunt of the painter Pablo Picasso whom he painted in The Portrait of Aunt Pepa. In 1896, when Picasso was fifteen, he was summoned by his uncle Salvador to draw a picture of one of his aunts Josefa. She was a spinster, characterised by her foul moods and extreme religiosity. She did not like the attention, and fussed about being immortalised. It shows, if somewhat unflatteringly but with remarkable virtuosity in the painting. Some of the qualities resemble my aunt. Or all aunts who defy the standard.

Picasso was nineteen when his aunt died. I was nineteen when I first met my aunt. There are no parallels between Picasso and me, but if we were to draw one, I did, back then, capture an image of my aunt’s immortality in my mind’s photo reel, and only now attempt to paint her final portrait in words.

On the night of the verdict, when my aunt died, I was on the phone, trying to console my mother in Kolkata. She was in sobs.

“I live alone, who will look after me if I slip into a coma,” she asked, quickly adding, “I don’t have a daughter-in-law to look after me.”

Any time now is a good time to tell her: I am what I am.

My only hesitation is that she might get a paralytic attack.

August 24, 2020

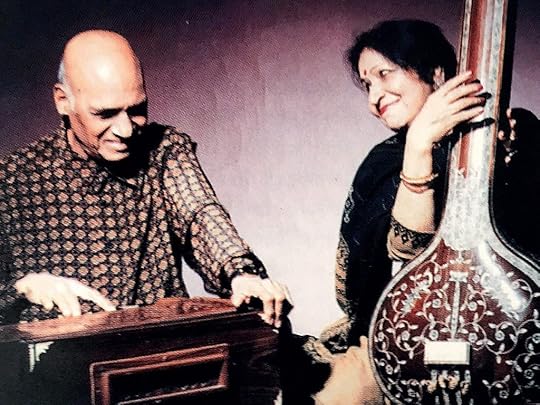

Jagjit Kaur: A Farewell Ghazal For Khayyam

Tum apnā ranj-o-ġham apnī pareshānī mujhe de do

Khayyam was on his last breath. A doctor confirmed to his grieving wife Jagjit Kaur that he had only his will to live.

‘He is in great pain but he trying to smile,’ the doctor said. She knew Khayyam was smiling to keep her alive.

After his fall from an armchair at home, he was admitted to the Lily cabin in a hospital in Juhu. Four days later, his inseparable wife was admitted for low blood sugar in the Tulip cabin next to his. The two wilting white blooms, she 88 and he 92, were trying to make a cheerful bouquet, perhaps for either one’s memorial.

Jagjit entered his bare, white hospital room reeking of a phenyl-sanitised odour. It had the sharp, acidic sting of a clean up after a body had been declared dead and removed. But Khayyam was breathing on borrowed time in a semi-conscious state.

She sat in a wheelchair by his side and took a deep, long breath to compose herself. He opened his eyes and felt at home. When was she not there beside him?

‘Do you remember how we met?’ he said.

She nodded. It was a nod for him to repeat. The story was as clear to her as light, as it was beginning to fog his memory.

‘I was walking on the Dadar foot over bridge. You were approaching from the other side. You were so strikingly beautiful. I stared at you. I thought to myself, she is the one. Yehi toh hai woh! You must have thought who is this idiot staring at me?’

She chuckled.

‘I did not think that,’ she said. ‘I was going to shout when you followed me but when you introduced yourself as a music composer, I was relieved.’

She knew the beats of this story by heart. She repeated after him to keep him in good humour.

‘Haan, you have taken care of this emotional fool for so long. I am so blessed,’ he said. ‘Woh mulaaqat shareeq-e-hayaat mein badal gayi’ (That brief meeting made you my life partner)

This was her cue to weep. She did not want to appear weak. She cleared her throat.

‘Chaliye purani baat chhodiye’ (Leave all this nostalgic talk) she said. ‘What do you want for lunch?’ she said.

‘Bas ek gaana thoda gunguna do’ (Please hum a tune for me) he said.

Dekh lo aaj humko jee bhar kehttps://medium.com/media/d7aa9a4c97c0020349b5e13e92469ba1/href

Koi aata nahi hai phir marr ke

***

Look at me with all your heart

No one returns after death

‘Oh ho, why are you thinking of death?’ she said. ‘You have such a long life.’

He held her hand and said, ‘We both know the truth.’

Hot tears rushed down her pale cheeks. The truth had snapped her hold over them.

‘I am worried for you,’ he said.

‘But that it causing you immense pain,’ she said. ‘Let go of the worry.’

‘I will. I promise,’ he said. ‘I just want to be sure you will be happy without me.’

‘Is that even possible?’ she said, a half-smile returning to her lips. ‘I will try.’

She understood that the only way to release him from his agony would be the assurance of her soothing voice.

‘Accha,’ she said. ‘I will sing a song. Just stay with me, ok? She patted his hand and looked up at the ceiling to prepare herself.

tum apnā ranj-o-ġham apnī pareshānī mujhe de do

tumheñ ġham kī qasam is dil kī vīrānī mujhe de do

***

Give me your grief and sorrow, give me your distress

Promise to take an oath, give me your heart’s emptiness

No sooner had she sung the first stanza that she felt his feeble hand finding its strength by holding her finger.

ye maanā maiñ kisī qābil nahīñ huuñ in nigāhoñ meñ

burā kyā hai agar ye dukh ye hairānī mujhe de do

***

I know I am not worthy of help in your eyes right now

There’s nothing wrong if your give me your suffering

His hand was now holding hers. She looked down at his crinkly face. Blood was flushing his cheeks. Her singing had kept him alive through good and bad times.

maiñ dekhūñ to sahī duniyā tumheñ kaise satātī hai

koī din ke liye apnī nigahbānī mujhe de do

***

Let me also see how this world troubles you

For a while let me keep a watch over you

As she sang the stanza, she felt him tighten his grip on her hand. It surprised and interrupted her cadence. She looked down again. His mouth was open. His eyes were empty. Death froze him like he was staring at her calm face for the very first time.

https://medium.com/media/9e32b0dc236e0b0ea7d5c5b979fccdd5/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.

August 22, 2020

Kishori Amonkar: Between The Notes

She struggled to place her voice in a room where her mother’s voice towered.

Kishori was twenty-five when she lost her voice. Her mother Mogubai said it was only an interruption in her sadhana (practice) and she would recover it soon.

‘Your voice has reached its pinnacle. It will return through you. It is as sign that your voice no longer belongs to you but to your listeners. They are the sadhya (destination) it desires,” she said.

Kishori was trying to comprehend her mother’s complex words with a poker face when Mogubai switched. ‘You are right now in a spiritual state of silence before the storm,’ Mogubai tried to cheer her up.

Kishori forced a smile. For her, her voice was a dialogue with the divine, and that had stopped. Her daily riyaaz had stopped. She was upset. On her mother’s insistence after consultation with a sadhu, she began taking ayurvedic herbs to restore her voice.

One uneventful morning, she was standing in her room, looking out of the window, watching the breeze tickle the leaves of a peepal tree. A lilting sound reached her ears like the tinkling of silver bells. A leaf danced in the air and floated into her palm when she stretched a hand out for its free fall. She chuckled. A geyser of notes began to rise up her larynx. Her mother was rehearsing in the next room, reaching for the ‘re’ note in raag Shuddh Kalyan. Kishori tried to grasp the ‘re’ of raag Bhoop, soaring in the opposite direction of her mother’s voice. Her voice returned with wings. She sang like a bird in flight.

Mogubai had to stop singing and walk into Kishori’s room. She watched her daughter with pride. Mogubai had taught her raag Bhoop for fifteen months straight. It had dried Kishori’s voice. The voice had returned after two years of complete silence. Mogubai said her voice could induce a trance-like effect in listeners.

‘Your voice has finally found its instrument. Remember that you are a tanpura now. You will have to be more careful with this voice,’ Mogubai said. ‘It is not for entertainment.’

Kishori looked at the glazed leaf in her palm as if it was a feather that had fallen off her back in flight.

Kishori’s new voice worked like a miracle. Fans flocked to concerts like devotees seeking epiphany. One thing lead to another, and soon enough Kishori was singing a solo in a film. Mogubai objected to Kishori singing the title song Geet Gaya Patharon Ne in the eponymously titled film. The song’s popularity announced her entry into film music but it was short-lived.

https://medium.com/media/e77a0ea07ad4747b386ad1beccc04d9d/href‘You will not touch my tanpura,’ her mother said. ‘We don’t sing for money and fame.’

Kishori did not return to film music. She became her mother’s most devoted pupil, often submissively allowing herself to be used as an example to set a standard of intent in the music room. Mogubai would sing the sthayi and the antara just once or twice to insure Kishori was focused. She wanted Kishori to surpass her own singing skills, and that required training Kishori with rigidity.

Twenty-five years later, when Kishori composed and sang in another film Drishti, Mogubai reminded her that the filmmaker would misuse her tunes. A lovemaking scene featured Kishori’s vocals. It naturally infuriated Mogubai, a traditionalist who wished the best for her daughter. Yet again, she reminded Kishori not to be swayed by glamour.

‘Why do you not listen to me?’ Mogubai said. ‘When will you do your riyaaz if you waste you time in films and concerts?”

With her head bowed, Kishori tried to contain the rebel growing older inside her. Time and again her mother was correcting a version of herself in her daughter. Kishori was a bird shedding her feathers in an open cage.

After her mother’s death, Kishori became a stickler like her mother. She spent ten to twelve hours in practice. When she stepped out, she reminded others that she was in communion with the divine. She grew irritable with an undisciplined audience, did not talk to the media, and was impatient with inefficient show organisers –things that she had seen her mother silently suffer.

Kishori’s voice had now begun to show signs of wear and tear. She would arrive late on stage and start by clearing her throat, take occasional sips of water and stretch a taan to climb octaves and reach shrutis (micro-notes). An hour would pass without her reaching the raag she was trying to scale, sometimes with great difficulty. Listeners could intuit a range of emotions, from sadness to happiness, but patience was key to both audience and performer.

Although she had her own identity, she was beginning to sound more and more like her mother. It bothered her that she was turning into her mother. Kishori had to find a way to communicate to her mother that she no longer needed her guidance.

At age 84, Kishori decided to perform her final concert to announce her sabbatical from singing. Wearing her trademark big red bindi, glasses, and her hair in a loose bun, she got up on stage draped in a shot-silk saree with a red and gold border. Holding the swaramandal in one hand, adjusting the pallu of her saree across her shoulder, she was a picture of dignity and grace. She sat on a white gaddi decorated with artificial flowers and accompanied by her musicians on the tabla, harmonium, violin and tanpura.

An hour into her performance, the audience was enthralled by her khatkas, meends, gamaks, and murkis — cluster of ornamental notes. Midway through an alaap, she sang Payaliya Jhankar in raag Puriya Dhanashree. She heard a tinkle of silver bells. She opened her closed eyes and looked up into the audience. She saw her mother, standing, and smiling. Kishori believed that when she hit the sublime note of a raag, it manifested itself in person. She could reach her mother through this abstraction in music.

https://medium.com/media/4fffd877f68ed0225f96c72abcb9cbd7/hrefThe transcendental effect of her voice had not only reached its audience, but also herself, like a leaf wilfully resting in her own palm. Her invocation had brought her mother back. Kishori ended the concert without informing the audience about her break from music. She didn’t need to. Her mother’s presence in the audience confirmed it. They were not one and the same.

Kishori died peacefully in her sleep a week later.

Her swaramandal was gifted to a music school. Students rushed to touch the sacred relic. It held her touch, her notes, and her soul-stirring voice, like a leaf dancing in the air, suspended somewhere between the here and the eternal.

https://medium.com/media/be7ecacb1b2f39ac2e9f1918d747e921/hrefDisclaimer: This is a work of fan fiction or more formally known as real person fiction. It is not for any commercial use. Read more on Real Person Fiction here.