Jennifer Kloester's Blog

December 30, 2022

My Lord John – The One Unfinished Novel

The magnificent double-page cover for Georgette Heyer’s last novel and designed by Edward Mortelmans. The Bodley Head 1975Her death came as a shock

The magnificent double-page cover for Georgette Heyer’s last novel and designed by Edward Mortelmans. The Bodley Head 1975Her death came as a shockOn 4 July 1974 famed author Georgette Heyer died. She was 71 and over her fifty-year career had written 55 novels and an anthology of short stories. At the time of her death she was selling a million copies a year in paperback and fifty years after her passing she is still selling. An international bestseller, her death came as a shock to her fans around the world and many of them wrote to her publisher at the Bodley Head to ask if there were any unpublished manuscripts among Georgette’s effects that might yet be put into print to delight her readers one last time. Sadly, there were no completed manuscripts – but there was one unfinished novel that, with some attention, could perhaps be published posthumously. The novel was My Lord John and this is its story.

The 1977 Pan edition of My Lord JohnRAISED ON SHAKESPEARE

The 1977 Pan edition of My Lord JohnRAISED ON SHAKESPEARE Georgette Heyer was raised on Shakespeare. From an early age she engaged with the works of the Bard and as an adult found much to intrigue and inspire her in the plays known as the ‘Henriad’. These were the four plays about three of the kings of the great English Plantagenet dynasty (1154-1485): Richard II, his son, Henry IV, and his son, Henry V. It was this latter monarch which, in 1939, Georgette decided would make a fascinating subject for a new book. She had just finished The Spanish Bride, set during the Napoleonic Wars, while at the same time war was on England’s doorstep. Beginning with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany on 1 September, through the ‘Phoney War’ and into 1940 with the eventual overrunning of France and Belgium in May, inevitably war was paramount in people’s minds. To Heyer, Shakespeare’s Henry V probably felt relevant given that it is a story about war, patriotism, and immense courage in the face of overwhelming odds. It is also a play about an English victory which features Henry V’s famous ‘band of brothers’ speech with which the king ignites his troops before the Battle of Agincourt. There were literary riches to be mined here and Georgette wrote enthusiastically to her agent about her idea for the book. She was disconcerted, however, to received a less-than-encouraging reply. In mid-December 1939 she wrote back to Moore to say:

My dear L.P.! I do hope you will rid your mind of the idea that Henry V will be as faulty a work as the Conqueror! I never was more depressed than when I read your grim prophecy. And if it isn’t a damned sight better than the Army ( which has always filled me with a sense of satisfaction) it is time I packed up.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 13 December 1939

1983 Pan Edition of My Lord John‘I HAVE LOVELY IDEAS FOR MY BOOK ON HENRY V’

1983 Pan Edition of My Lord John‘I HAVE LOVELY IDEAS FOR MY BOOK ON HENRY V’Of course, Georgette Heyer would never have ‘packed up’ for she was a compulsive as well as a compelling writer (and The Conqueror was a masterly achievement) and she assured Moore that ‘I have lovely ideas for my book on Henry V. I think I shall call it Stark Harry.’ But her confident assurance did not play out as she had hoped. The book she was planning would prove to be a challenge unlike any she had yet or would ever encounter in her decades-long writing life. Throughout her career, Georgette had always written quickly and even in the last years of her life she was able to pen a 120,000 word novel in just a few months. The story of the Lancaster family, however would be different. At first, her focus was on Henry V and the book was to be called Stark Harry. Two years later – and most unusually for Heyer – she had written nothing of the new novel. Instead she had published two historical romances and a detective novel and was now immersed in Penhallow. In 1941 this was the book that obsessed her from the moment it had fallen fully-formed into her mind.

STARK HARRY STILL ‘PENDING’She had not forgotten Henry V, however, for in February 1942, she wrote again to Moore to report that Frere had written to her to say that:

He will publish whatever I want to write, & thinks well of my suggestion that I should do something more worth while than these frippery romances. He says good books are selling better than bad ones, & tells me Macmillan has subscribed over 10,000 of Miss West’s new magnum opus! [This would have been Rebecca West’s non-fiction book, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, about the causes of the Second World War.] Isn’t that a cheering thought? Anyway, Frere says, Write what you feel like, & take as long over it as you want to, & throw off the ‘tec novel & the serial in between whiles. He says “you can do them on your head” – little recking that at the moment I couldn’t even do them the right way up. So it may well be that I shall have a stab at StarkHarry. What do you think about it? (Don’t you like the spurious diffidence with which I consult you & Frere about what I’ve really made up my mind to do anyway? But in these bad times I really would be amenable to reason, if you both advised me against any dire course.)

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, February 1942

A month later Stark Harry was still ‘pending’ and the war was taking its toll. It may have been the harsh realities of the Second World War that caused Georgette to shelve her medieval book, but whatever the reason, it would be another seven years before she returned to the idea.

1992 Arrow edition of My Lord John‘FETTERED EAGLE IS GOING TO BE GRAND!’

1992 Arrow edition of My Lord John‘FETTERED EAGLE IS GOING TO BE GRAND!’The War ended in 1945 and four years later, in April 1949, having finished another delightful Regency novel in Arabella, Heyer reported being ‘lost in the 15th century’. A month later, in the midst of various family issues and ‘general turmoil’, Georgette had managed to write enough of the new book to report that ‘Fettered Eagle is going to be grand!’ By now, her vision had enlarged and her focus was no longer solely on Henry V. Instead, she had decided to tell the story of the Lancaster family with Henry’s younger brother John as the main character. John was John of Bedford, the third son of Henry IV and the grandson of John of Gaunt, the first Duke of Lancaster and the founder of the Lancaster royal dynasty. John was an important figure in the era and Georgette had always felt that he should have been better known. In fact, her new novel was – in part – intended to change people’s understanding of this vital and influential period of English history. However, she also wanted to write a book that would make the critics and the academy sit up and take notice. The fact that by 1949 she had written thirty-five novels and that many of them had been highly regarded and praised on both sides of the Atlantic did not seem to resonate with her. Heyer wanted more. All her life she would suffer (as so many authors do) from an overt lack of belief in her own ability. If, underneath, she knew that what she wrote was good, it was not something she could or would openly accept – at least not without the corroborating opinions of those people who apparently ‘mattered’.

‘FORGET BARBARA CARTLAND’ Barbara Cartland, Photo: Allan Warren, Wikimedia Commons

Barbara Cartland, Photo: Allan Warren, Wikimedia Commons Barbara Cartland’s Knave of Hearts renamed The Innocent Heiress in 1970Georgette was incensed when she learned of the tagline ‘In the Tradition of Georgette Heyer’ being used to promote Cartland’s novels.

Barbara Cartland’s Knave of Hearts renamed The Innocent Heiress in 1970Georgette was incensed when she learned of the tagline ‘In the Tradition of Georgette Heyer’ being used to promote Cartland’s novels. The new book was complex and, in terms of research, demanding. There were also other demands on Georgette’s pen for she could not afford to disappoint her eager public and forgo writing her annual novel. Having finished The Grand Sophy in the spring of 1950 she finally returned to her medieval novel. It was by now a whole year since she had told her publisher that Fettered Eagle is ‘going to be grand’ but she was at last immersed in the book she was now referring to as ‘Prince John of Lancaster’ and writing ‘Chapter 3 Beau Chevalier’. Unfortunately, she was fated to be interrupted again. This time she was disturbed by reports of plagiarism. A fan had written to tell her that an author by the name of Barbara Cartland had been ‘immersing herself in some of your books and making good use of them’. Georgette did not recognise the name but she certainly recognised the many ‘borrowings’ perpetrated by Miss Cartland when she read that author’s first-ever historical novel and its two sequels. A Hazard of Hearts, A Duel of Hearts, and Knave of Hearts, would consume hours of Georgette’s life as she cross-referenced the many ‘lifts’ (as she called them), between half a dozen of her own books and those comprising Cartland’s ‘Hearts’ trilogy. It was a frustrating episode and as Georgette explained:

a complete bore, and is wasting my time. Reading my own back numbers is Death – particularly when I’m at work on something quite different. Held up for a day, too, trying to get at the rights of a scandal about Bishop Beaufort.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore letter, 21 May 1950

Georgette tried hard to forget Barbara Cartland but it was difficult. As she told her publisher at Heinemann: ‘I can’t get the wretched business out of my head, and haven’t written a word of John for days.’

Georgette cared deeply about accuracy and detail. Her medieval notebooks are crammed with information.‘SHE WAS A PERFECTIONIST’

Georgette cared deeply about accuracy and detail. Her medieval notebooks are crammed with information.‘SHE WAS A PERFECTIONIST’Eventually, Georgette was able to move on from the plagiarism affair and return to her medieval novel. It was an absorbing undertaking but one which – unlike her usual writing experience – took her far, far longer than perhaps even she had anticipated. She and Ronald had already visited France, there to see the site of the Siege of Orléans and John of Bedford’s tomb among other historic places of interest. She taught herself medieval English and took pleasure in deciphering early documents and garnering a large vocabulary. The following year, in the autumn of 1951, her novel took her to ‘the north country. A pious pilgrimage, in aid of my mediaeval book.’ Returning home, she triumphantly declared that she had ‘put no fewer than 12 ancient castles in the bag!’ And yet, once again the novel languished. It is perhaps not unreasonable to ask why it took Georgette Heyer – an author who was able to consistently write an enduring classic in only six weeks – so long to write My Lord John? It is Ronald who best answers the question in the Preface to the book which was eventually published the year after her death:

Her research was enormous and meticulous. She was a perfectionist. She studied every aspect of the period –history, wars, social conditions, manners and customs, costume , armour, heraldry, falconry and the chase. She drew genealogies of all the noble families of England (with their own armorial bearings painted on each) for she believed that the clues to events were to be found in their relationships… Her notes filled volumes. For the work, as she planned it, she needed a period of about five years’ single-minded concentration.

Ronald Rougier, Preface, My Lord John, Bodley Head, 1975

This was not to be given to her and, more importantly, it was not something she would ever take for herself – not even in the 1960s when her income was assured and she could have, if she had wished, given up writing Regencies and focussed solely on My Lord John. Perhaps it is here that the reason for this one unfinished novel lies. Perhaps, in her heart of hearts, Georgette knew that the task she had set herself was too great; that the book she had envisaged could not be written as her other books had been written –with a closely-knitted plot, wit, humour and sparkling dialogue. Nor could she create her usual cast of memorable characters, so that even the minor players remain with the reader long after the book is ended. She was shackled by history and by her long-held belief in the importance of facts. A close look at the novel itself is enlightening.

Georgette kept several large notebooks crammed with details of medieval life.

M

y Lord John

Georgette kept several large notebooks crammed with details of medieval life.

M

y Lord JohnThe historical tale was intended to be a grand one, full of twists and turns, battles and betrayals, plots, conspiracies, friendships, murders and beheadings, but its subject matter would prove to be too vast, even for so skilled an author as Georgette Heyer. And it was not only the breadth of the topic, nor the fact that Prince John’s life was, for its time, a long and complicated one. John’s story begins in childhood and carries through until his twentieth year, at which point Georgette ‘laid John of Lancaster in lavender’ and did return to him until just two years before her death. There is much in the novel that is worthy and plenty of scenes where Heyer’s inevitable talent shines through. The problem, in my estimation, is that the story has no clear overarching plot or climax. Even in her most serious historical novels such as The Conqueror, An Infamous Army, Royal Escape, or The Spanish Bride, Georgette was always driving towards a dramatic conclusion. Whether it be William’s coronation at Westminster, the breathtaking denouement of Waterloo, or King Charles II’s eventual escape to France, the action in these novels is constantly building towards an end-point. John of Bedford’s life – though full of interesting moments and events – is one of shift and change without an overriding tension to keep the reader going. He is a worthy figure, too, but, try as she would to make him live (and there are scenes where he comes splendidly into clear focus), Georgette could not give John the same sort of three-dimensional presence that she had always been able to achieve with the characters in all of her other books.

More historical narrative than novelIn part this was because My Lord John is more often a historical narrative than a historical novel. While the story is interspersed with vivid scenes of life, events and places, such as her description of Pontefract Castle where Richard II is said to have died, and there are moments of classic Heyer dialogue, the weight of history is a continual constraint. Unlike her other historical writing in this last book Georgette failed to wear her learning lightly but thrust medieval words and phrases into the text as if their mere presence would be enough to convince her reader of a fifteenth-century milieu. she was, of course, not a trained historian, but she sti took history very seriously. She believed in going to the sources, in finding the ‘facts’ and adhering to them as meticulously as possible. Her contract with her reader, even in her most lighthearted books, was that they could trust her history. Whether a modern historian would agree is irrelevant for it is what Heyer believed and it was upon that basis that she wrote her historical novels. My Lord John proved a difficult tale to tell because Georgette could not tell it with all of her usual verve and style. Inevitably, there was a large cast of historical figures to introduce to the reader, and perhaps, as in The Conqueror, this might not have mattered had she been able to offer her readers a strong plot with a clear beginning, middle and end. Instead, such was the diversity of people, essential historical moments needing explanation, and the impossibility of keeping her main character onstage long enough to establish him as someone for readers to care about, that it proved hard to hold the narrative together. Perhaps it was inevitable that the book would end by being uneven in both tone and intent. It seems likely that Georgette’s vision of the novel would never be met and she discovered this in the process of trying to create a compelling story out John of Bedford’s life story. She was a highly intelligent person and a truly gifted writer with a remarkable instinct for what worked in a novel. She must have seen – must have known – that this book, this one book out of so many, was never going to work. And so, she never finished it.

Perhaps Jane Aiken Hodge said it best:

‘Unfinished, her medieval project was at once a splendid hobby and a claim to the respectability denied to ‘mere’ entertainers. Finished it might have proved a sad disappointment.’

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, The Bodley Head, 1984, p.78

The 1975 Bodley Head edition of My Lord John with its sumptuous medieval cover. Georgette would have approved.‘It is definitely GOOD, Max!’

The 1975 Bodley Head edition of My Lord John with its sumptuous medieval cover. Georgette would have approved.‘It is definitely GOOD, Max!’It was to be many years before Georgette finally returned to My Lord John. Just eighteen months before her death she re-read what she had written and was moved to write to her friend and publisher, Max Reinhardt to say:

‘I got out my unfinished medieval book, and ever since have been toying with the idea of bringing to an end, with the death of Henry IV. For it is definitely GOOD, Max! When I read it, after heaven knows how many years, and when I had largely forgotten it, I found it absorbingly interesting!!! But it is not in my usual style, and I can’t make up my mind whether to publish it or not. I think I must be guided by you, and (if you can be bothered with it) mean to send you the three completed parts. The third is still unfinished, and I shall have to put in a lot of work, mugging up the sheaves of notes I took for it. But it you think it would be disastrous to publish it – well, I’ll still finish it, but will then put it away to be published after my death!’

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 27 November 1972

In the end, her wish was fulfilled and My Lord John was published the year after her death. It sold in large numbers and was extensively reviewed wherever it was published. Without exception all of her reviewers praised her research, her knowledge and her skill as an outstanding storyteller, but the majority view was that My Lord John did not match the standard set by her Regency novels. For Georgette Heyer was, above all, a master of comic irony and her most beloved books are a mixture of brilliant wit, vivid dialogue, memorable characters and ingenious plot given to the reader on page after page of perfect prose. In My Lord John the opportunity for these things was decidedly limited by the facts of history. The scope was too huge, the characters too disparate and the timeline of John’s life too fragmented for her to create her usual brilliant, cohesive story. The book will always be readable, but for most of Heyer’s readers it will never be a favourite. Although some people consider it to be among her best books, most find My Lord John to be a candle when compared to the shining light of her other books. I think she knew it, but she held on to her medieval dream until the end.

September 9, 2022

Lady of Quality – the End

Georgette Heyer’s final novel about a strong, independent woman

Georgette Heyer’s final novel about a strong, independent woman A strong, dedicated woman, HM Queen Elizabeth II died 8 September 2022HM Queen Elizabeth II

A strong, dedicated woman, HM Queen Elizabeth II died 8 September 2022HM Queen Elizabeth IIWhile this post is about Georgette Heyer’s last complete novel, it seems somehow fitting to pay tribute to HM Queen Elizabeth II who died today (8 September 2022) at the age of 96. Whether you’re a royalist or a republican, Queen Elizabeth’s standing in the world was unmatched. She was a remarkable woman, dedicated to her people, kind, honourable, and unswerving in fulfilling her duty – as she had promised to do upon coming to the throne more than seventy years ago. She was a “Lady of Quality” and someone whom Georgette – like so many others – greatly admired. The two women met in 1966 when the Queen invited Georgette to lunch at Buckingham Palace (you can read about it here https://jenniferkloester.com/georgettes-lunch-with-the-queen/) and Georgette and Ronald also attended a number of Her Majesty’s garden parties. The Queen was a fan of Heyer’s novels, and after their lunch, she visited Harrods where she bought a dozen copies of Frederica and told the department manager that she thought Georgette “formidable”. In her turn, Heyer described the monarch as having “a merry twinkle and quite a lively sense of the ridiculous”.

The 1972 Bodley Head edition of Georgette Heyer’s last Regency novel – the aptly-named Lady of QualityRestraint

The 1972 Bodley Head edition of Georgette Heyer’s last Regency novel – the aptly-named Lady of QualityRestraintBoth the Queen and Georgette believed in restraint and discretion. Theirs was a generation that valued privacy. For them, one’s public life was to be kept separate from one’s personal, private life. Georgette believed in this very strongly and lived her entire adult life according to this precept. The Queen, however, did not have that choice. Although, in the early years of her reign, she was able to maintain a decided separation between her public and private worlds, as the years passed, and technology took hold, people’s private lives became ever more a saleable commodity. Georgette, of course, died in 1974; the Queen has lived on for almost another half century. In those fifty years change – especially technological change – has been the marker of many people’s lives. While Elizabeth II has remained a constant throughout these past seventy years, change has found her too. This was never more clear than in 1997 after the death of Princess Diana when the Queen was strongly criticised for not speaking publicly about the tragedy. But people of her generation did not believe that expressions of grief were for public consumption. They had been taught to control one’s emotions. By the late twentieth century, however, the Queen’s instinctive reaction to Diana’s death – to keep her family close and her two young grandsons shielded from public gaze – was no longer acceptable to a grieving public. As the BBC explained:

Many of her critics failed to understand that she was from a generation that recoiled from the almost hysterical displays of public mourning that typified the aftermath of the princess’s death. She also felt that as a caring grandmother that she needed to comfort Diana’s sons in the privacy of the family circle.”

BBC, 8 September 2022

The Signet edition of Lady of QualityThe last novel

The Signet edition of Lady of QualityThe last novelOne of the hallmarks of Heyer’s novels is emotional restraint. It is a sign of a character’s worth. The lachrymose, hysterical, “tragedy Jills” and “tragedy Jacks” of the books are almost always secondary characters of questionable virtue, often manipulative and usually weak. Lavinia in The Black Moth, Tiffany in The Nonesuch and Mrs Dauntry in Frederica are but three example of people who either cannot control their passions or use public displays of emotion to achieve their ends. Georgette’s last completed novel, Lady of Quality, has two characters who are the polar opposites of each other in this regard. The heroine, Annis Wychwood, despite a good deal of provocation, is a model of emotional restraint. Her companion, however, the garrulous and irritating Maria Farlow is a woman who gives tongue to every thought and actions to every emotion. Maria is not a bad character – Heyer’s characters are complex and rarely painted solely black or white – but her lack of restraint puts her beyond the pale for both Annis and the reader. Lady of Quality is a reflective book. Perhaps Heyer’s most reflective. The heroine has created a pleasant life for herself: living independently in Bath, famed for her beauty and liked by all in her social circle. And yet, she is not content. Her life is small and constrained by the rigid social protocols of the day. Society says she must have a companion, but Maria is no true companion in terms of interests or intellect. Heyer sets the scene perfectly for the arrival of three people who will change everything.

Georgette wrote her early novels with a fountain pen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Georgette wrote her early novels with a fountain pen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons“the grace, the marvels and the sheer magic”I am longing to know what you think of our new abode – and longing even more to see you both, and to remember that I am not only a Sister, and a Housewife, but a NOVELIST as well! At the moment, I am too tired even to think about a new book, but this has happened to me many times before, and I know that suddenly an Idea will burst upon me – after which I shall forget that I’m a Sister and a Housewife, and shall plunge deep into the early XIXth Century, and be lost to Society until I have written THE END!

Georgette Heyer to Max and Joan Reinhardt, letter, 23 December 1971

1971 was another of Georgette’s rare years without a book. She had been unwell and was easily exhausted. In November, on finding the flat too noisy, they had finally left Jermyn Street and moved to a spacious apartment in Knightsbridge with views across Hyde Park. Christmas had not been easy that year, for her brother Frank’s wife, Joan, had died only ten days before the planned festivities and Boris’s wife, Evelyn was very unwell with kidney problems. Georgette, too, had suffered from poor health and a series of accidents had left her with a gashed ankle and bruised ribs. A month later she broke her leg. Perhaps it was the sudden advent of an unexpected letter that prompted her to start a new novel. In mid-January Georgette received a charming letter from an American reader who wrote to say, among other things:

I am not given to the writing of letters of praise to famous individuals. In this instance, I am literally compelled to do so by a feeling of gratitude so strong that the peace of my nerves demands an assuaging through the process of thanking you for the grace, the marvels and the sheer magic of your writing. Your Regency novels are read and re-read…time after time. As one who is involved in a business of intense pressure (I direct senatorial and congressional election campaigns), I have only to turn to your pages to find a measure of charm, a flow of personal relations that allows one to slip into the period now so removed and, above all, an intense joy of your offerings. Beneath the easy concourse of your characterizations and plot, there is real meaning for me in the proceedings of the a day in which the surface of manners allowed a more graceful and honest meeting of gentlemen than the sheer power of our own.

Mr Roy Pfautch to Georgette Heyer, letter, 31 December 1971

The 1974 Pan edition of Lady of Quality.“Wrestling with a new book”

The 1974 Pan edition of Lady of Quality.“Wrestling with a new book”Such sincere and effusive praise from a man of standing meant a lot to Georgette and she wrote a graceful reply to Mr Pfautch in which she assured him that: “I’m not really as good as you think I am, but it is very nice to be told I am!” Perhaps it was this letter that prompted Georgette to begin writing again, for only a week later she told her publisher, Max Reinhardt, that he could expect a new book from her in time for autumn publication. Max was delighted but Georgette would not find it as easy as she had in the past. Early in February she told her old friend, Elizabeth Anderson of Heinemann, that “I am wrestling with a new book, & finding my hand rather stiff, & my brain very woolly.” She persevered, however, and though she felt she was “making very heavy weather” of it, her friend and agent, Joyce Weiner, assured her that “You know it will come of itself, that the plot, action, ‘argument’, what you will, is secondary to the characterisation, and the dialogue will flow once you get going”. Joyce was right. Georgette’s lifelong skill reasserted itself and gradually the book took shape. By April, she had made good progress and could triumphantly tell Reinhardt that:

Ronald says the operative words are “the rudest man in London,” and I shouldn’t wonder at it if he’s right… I’ve left him making himself thoroughly obnoxious to Lord Beckenham, in the Pump Room, and must go back to him, and think of a few more poisonously rude things for him to say… I have only to add that Mr Carleton is not merely the rudest man in London, but has also the reputation of being a Sad Rake, to convince you that he has all the right ingredients of a Heyer-Hero.

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 27 April 1972

Annis & Oliver“Annis, Oliver, Lucilla & Ninian–four wealthy people, all dissatisfied with their lives. But in the rigid society of Regency England, could they find ways to change them?”

Title page of the serial, Woman’s Own, 14 October 1972

Oliver Carleton, the hero of Lady of Quality is one of Heyer’s care-for-nobody heroes. He and the book’s heroine, Annis Wychwood, on first meeting, appear to be polar opposites. Instead, they discover that they are each possessed of a sharp intelligence, a quick wit and a shared sense of humour. Annis, brought up in strict propriety, has already shocked her relatives by choosing to use her considerable fortune to set up her own house in Bath – with the requisite companion, of course. Change is thrust upon her, however, when she rescues nineteen year-old Lucilla, and her childhood friend, Ninian, from a carriage accident and takes them home. Soon afterwards, Lucilla’s disreputable uncle arrives to find out who this woman is who has taken charge of his niece. Inevitably, sparks fly and against all expectation, Annis finds herself drawn to this obstreperous and outspoken man. Readers sometimes comment on the obvious similarities between Lady of Quality and Black Sheep and there are certainly several points in common. But the two books also differ in a couple of important and interesting ways.

In this book, more than in any other of Heyer’s, the reader is party to many of Annis’s inner thoughts. Her doubts about Oliver, marriage, and the right future for herself and her household all come to the fore. Oliver Carleton is unlike any man she has ever know. In courting her he has “employed no arts at all” but has still disordered “her well-regulated mind”. Here intellect and rational thought clash with emotion as Annis struggles to work out whether it is worth giving up her independence (a rare commodity for women in the Regency era) to marry a man who – when considered rationally – should not appeal to her at all. A close reading of this, the last of Georgette Heyer’s many wonderful and perceptive novels, tells us a good deal about Georgette’s own thoughts and feelings about love, relationships and what makes a good marriage. There are elements of her own husband, Ronald Rougier, to be found in the characters of both Oliver Carleton and Annis’s brother, Sir Geoffrey, but it is Annis who compels us as she struggles to understand her own feelings. Everything about Oliver Carleton is new and unexpected and in the end she finds herself contemplating the very nature of love:

“It was easy enough to understand why she should so often hate him; nearly impossible to know what it was in him that made her feel that if her were to go out of it her life would become a blank. Trying to solve this mystery, she recalled that he had told her not to ask him why he loved her, because he didn’t know; and she wondered if that was the meaning of love: one might fall in love with a beautiful face, but that was a fleeting emotion: something more was needed to inspire one with an enduring love, some mysterious force which forged a strong link between two kindred spirits. She was conscious of feeling such a link, and could not doubt that Mr Carleton felt it too, but why it should exist between them she was wholly unable to discover.”

Georgette Heyer, Lady of Quality, Pan, 1972, p.183

“a Light has Dawned on me”

“a Light has Dawned on me”Though it took Georgette a little longer than usual to write Lady of Quality, due to her continuing health issues, by May she had written most of the novel. She was struggling with exhaustion and it is likely that the cancer that would kill her just two years later had already begun its insidious attack on her lungs. Georgette still found enjoyment in life but she no longer took her regular trips to Fortnum’s or Harrods. Instead, she was content to spend time in Hyde Park among the trees, enjoying the flowers and the birdsong. In late May she wrote to Reinhardt with the good news that:

I think there are about 20,000 words still to be written, and it won’t take long to polish them off – now that a Light has Dawned on me. It dawned quite suddenly, this afternoon, at the eleventh hour, in fact! Until that thrice blessed moment I really didn’t know how to end the book for the only ending I could think of was so unsatisfactory that I grew more and more depressed. And then it came to me! And now that I know just what my goal is my brain and hand have become nicely lubricated, and I foresee no more difficulties ahead of me.

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 19 May 1972

She was right. The novel has a satisfying ending in which Miss Farlow is summarily dispensed with, Annis and Oliver agree to marry and – perhaps best of all – the final scene includes one of Georgette’s perceptive conversations between husband and wife. I like to think that there is something here of Georgette and Ronald in this, the very last, of Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels.

The 2019 Arrow edition of Lady of Quality

The 2019 Arrow edition of Lady of QualityP.S. I have read what I’ve written to Ronald, & he assures me that it’s not at all dull. I fear this may be the sort of heartening thing it is a husband’s duty to say, but I must admit that I didn’t find it as dull as I’d thought!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 19 May 1972

August 15, 2022

Happy 120th birthday Georgette Heyer!

Georgette loved orchids.

Georgette loved orchids.“So then we all went in to lunch, where the new secretary for Heron was presented, and I found an orchid on my plate!!!! As it is years since anyone gave me an orchid that quite made my day!”

Georgette Heyer to her publisher, 12 November 1968

Today, the 16th august 2022, marks one hundred and twenty years since Georgette Heyer’s birth. It is not hard to imagine her suprise and pleasure – were she alive today – upon discovering that her novels are still read and loved all over the world. Little did she know when she penned that first teenage story, that more than 100 years later, The Black Moth and most of her other novels would still be selling.

The 1929 Heinemann first edition

The 1929 Heinemann first edition The 2021 Centenary editionFrom its first publication in 1921 to its centenary celebration in 2021, The Black Moth has never been out of print.Georgette Heyer lives on…

The 2021 Centenary editionFrom its first publication in 1921 to its centenary celebration in 2021, The Black Moth has never been out of print.Georgette Heyer lives on…Most of my works would die with me, I fear; but one or two might continue selling for a while.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, 24 May 1941

Not many authors can claim to have created a genre, but Georgette Heyer may do so with pride. Her twenty-six Regency novels published between 1935 and 1972 established a world that felt real. So real, in fact, that today many authors have set their own stories there. But it is not only her Regency stories that bring hours of pleasure to readers. Georgette Heyer’s other historical novels – the Georgians, the medieval books, the swashbucklers, the Restoration novels and her Waterloo books – as well as her dozen detective novels continue to entertain a broad audience. Her superb prose, her clever plots, her brilliant dialogue, wit and humour, the wonderful endings and the characters who leap from the page and remain with you long after the last page is turned – it is all of this and more that make her books so beloved. She was a genius whose style and intelligence rendered her – as Colleen McCullough once said to me when I asked her if she read Georgette Heyer – “INIMITABLE!”

And so, to the late, great Georgette Heyer – a very happy birthday and may your memory and your books live on forever!

In 2015 Georgette Heyer was awarded a Blue Plaque in recognition of her literary achievements

In 2015 Georgette Heyer was awarded a Blue Plaque in recognition of her literary achievements Georgette Heyer would have been pleased and proud knowing her books were still read and loved

Georgette Heyer would have been pleased and proud knowing her books were still read and loved

July 15, 2022

Charity Girl – against the odds part 3

The Times masthead. Wikimedia Commons“It has left my withers wholly unwrung”

The Times masthead. Wikimedia Commons“It has left my withers wholly unwrung”On 1 October 1970, Georgette Heyer’s penultimate Regency novel, Charity Girl, was published. On that same day, The Times newspaper published a long article about Georgette, her readers and her novels. It was written by well-known author, intellectual and radio personality, Marghanita Laski, and it was not complimentary. Despite having promised Georgette that Laski’s piece would “makes amends” for past neglect, the literary editor, Michael Ratcliffe (possibly because he had not read Laski’s piece or because he had read it and thought it incendiary enough to attract attention), allowed the article to be published. While Georgette herself declared herself unperturbed by the article, it aroused a storm of protest from her readers, many of whom wrote to The Times as well as to Georgette herself and to Marghanita Laski. The Times published half a dozen of the letters under the heading “Miss Georgette Heyer’s Regency Novels” before the Editor declared the matter closed. They make for interesting reading and reflect the points of view of readers from across the social demographic. The letters are given below and it seems certain that they must have given Georgette a good deal of pleasure. Her own response to Laski’s article was expressed in a letter to her friend and former publisher, A.S. Frere:

Readers reply to Marghanita Laski’s “review” of Charity Girl“What a remarkably silly “review” of Charity Girl it was! I thought, as I read it, that I could have torn ME to bits far better than she did. Not that it has done me the slightest harm, so it has left my withers wholly unwrung.’

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter,

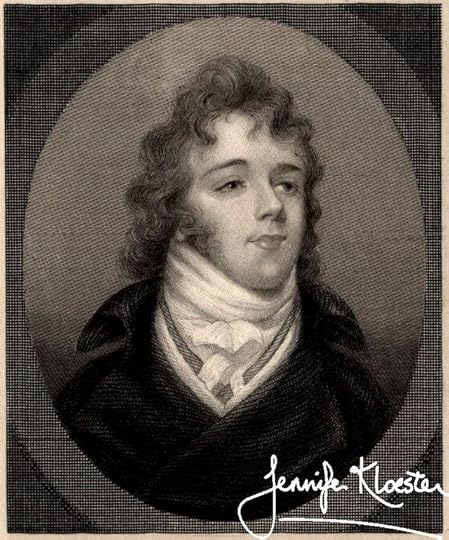

Beau Brummell – the ultimate dandy, arbiter of fashion and leader of society.

Beau Brummell – the ultimate dandy, arbiter of fashion and leader of society. Etching: Wikimedia Commons“the deductions … are perhaps open to question”

Sir, The deductions of Marghanita Laski (review, October 1) concerning the books of Miss Georgette Heyer are perhaps open to question. For instance, she asserts that “the heroes…are invariably dandies”—and what is a “dandy”? A dandy is one who by sartorial distinction, dictation of social conventions, or both, seeks to distinguish himself from the common herd. In fact, very many of Miss Heyer’s heroes “fail” to come into this category, for instance—the Marquess of Rotherham, Mr Miles Calverleigh, and Major Theo Darracot [sic – he means Hugo Darracott]. As for the authenticity of the Miss Heyer’s portrayal of Regency England, I would, from my own knowledge of the writings about that period conclude, contrary to Miss Laski, that the portrait is archeologically correct—sufficiently so to be of some importance to the social historian in his understanding of that era. Miss Laski has for critical purposes juxtaposed Georgette Heyer with Jane Austen in a distinctly inadmissible way—bearing in mind that Jane Austen was writing novels of contemporary manners for her contemporaries, for the absence of detail necessarily used by Miss Heyer to give a sense of period to her present readership being explicable because this detail’s existence was understood between the writer and the reader, and thus did not require inclusion. However, I must agree with Miss Laski that the lack of sexual motivation in the behaviour of the characters is too noticeable, and is a detraction from essential human authenticity, “Regency” or otherwise.

Yours faithfully,

Peter Arnold, letter, The Times 3 October 1970

Walking dress 1817 La Bell Assemblée. Wikimedia Commons

Walking dress 1817 La Bell Assemblée. Wikimedia Commons Walking dress 1813 La Belle Assemblée Wikimedia CommonsUnlike Jane Austen, whose readers lived in the world about which wrote, Georgette Heyer needed to explain period details to her readers.“Laski has not read the Regency novels very thoroughly…”

Walking dress 1813 La Belle Assemblée Wikimedia CommonsUnlike Jane Austen, whose readers lived in the world about which wrote, Georgette Heyer needed to explain period details to her readers.“Laski has not read the Regency novels very thoroughly…”Sir, Miss Marghanita Laski has obviously not read the regency [sic] novels of Georgette Heyer very thoroughly (review, October 1). This is understandable, as she doesn’t like them much, but necessary in order to generalize. In fact, there is dirt, plenty of mud, dust and blood; there is poverty in The Toll-Gate (working-class), Arabella (middle-class); religion of the ordinary Christian kind in evidence, more particularly in Arabella; an occasional [sic] political background (Bath Tangle and the war novels. There are squalid scenes in the streets, there is cruelty to children, to animals. There is noise. Certainly sex is limited. Miss Laski might have found more powerful indications of lustful sex in The Spanish Bride—in which the hero and heroine are actually happily married—or even The Infamous Army [sic], in which the physical attraction between Audley and Lady Barbara is plainly the chief reason for their relationship. I believe it is true that no married man is allowed to have a mistress, although he may visit her to say goodbye (The Convenient Marriage), but the heroes are permitted to carry on with other women both in the pages of the book and while the heroine is about (These Old Shades). The heroes are not all “dandified”, some go out of their way to be thought not so—Charles in The Grand Sophy—or don’t mind what they wear (Black Sheep), and actually the dandies are gently made fun of (Cotillion). People, men too, read Georgette Heyer because they find her books witty, entertaining, well-written—no doubt characters do “gaze up at” each other but so they do in Iris Murdoch—and the detail graphic, interesting and not unreliable. Even dogs and horses are marvellously real. They are romantic novels and as such can hardly put a mirror up to life n all its realities. So, of course, there are inanities, and however did those heroines disguised in men’s clothing “manage”? I am, sir, yours, &c.,

ROSALIND BELBEN, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

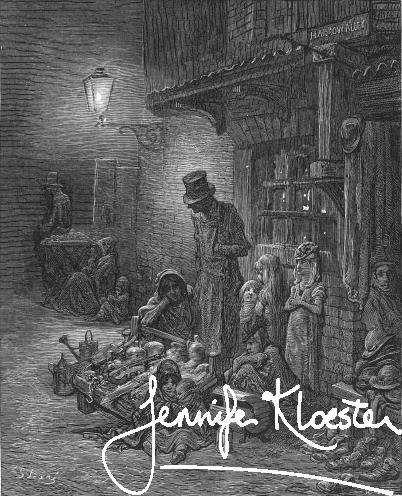

Heyer’s Regency novels were steeped in historical detail. Here is a slum similar to the one descirbed in Arabella.

Heyer’s Regency novels were steeped in historical detail. Here is a slum similar to the one descirbed in Arabella. Heyer reader Rosalind Belben wonders how Heyer’s cross-dressing heroines “manage” Heyer readers were quick to point out her historical detail as well as her appeal to women and to men.“appeal to educated men”

Heyer reader Rosalind Belben wonders how Heyer’s cross-dressing heroines “manage” Heyer readers were quick to point out her historical detail as well as her appeal to women and to men.“appeal to educated men”Sir, Marghanita Laski marvels that educated women read and enjoy the Regency novels of Georgette Heyer. But she appears unaware that they can also appeal to educated men. My father, Professor Sir Richard Lodge, a serious historian, introduced them to his family with much appreciation. My brother, Balliol, ex-schoolmaster and scientist, had an almost complete collection of them in paper-backs. They sparkle with wit and humour and make delightful escapist reading. Personally I can read them again and again and still unexpectedly chuckle aloud. The Reluctant Widow is my favourite. It is surely a curious criticism that there is so much detailed description of “food, clothes, furnishings, transport” in those Regency novels as contrasted with the novels of Jane Austen. Jane Austen was writing in the period, Georgette Heyer is writing of it and creating a picture by those careful details. If it is a glamourised picture, so much the better! There is little glamour about the modern novels which Marghanita Laski prefers, and which I return to the library after reading a few pages. Chacun a son goût! Yours truly

MARGARET B. LODGE, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

Sir Richard Lodge was Professor of History at the University of Edinburgh from 1899-1925 Photo: National Portrait Gallery UK

Sir Richard Lodge was Professor of History at the University of Edinburgh from 1899-1925 Photo: National Portrait Gallery UK Baron Somervell of Harrow was a barrister, judge and politician who served as Solicitor General and Attorney General from 1933-1945 Photo: National Portrait Gallery UKFrom her first novel in 1921, Georgette Heyer has appealed to readers regardless of gender or social status.“refreshment and amusement”

Baron Somervell of Harrow was a barrister, judge and politician who served as Solicitor General and Attorney General from 1933-1945 Photo: National Portrait Gallery UKFrom her first novel in 1921, Georgette Heyer has appealed to readers regardless of gender or social status.“refreshment and amusement”Sir, Referring to Miss Marghanita Laski’s review, The Appeal of Georgette Heyer, I think it is just the “lack of sex” decried by Miss Laski that appeals so much in Miss Heyer’s books. I read and enjoy many of the novels published today which contain very frank and open relationships, but I turn to Georgette Heyer for refreshment and amusement—the humour of Miss Heyer is not mentioned by Miss Laski—as I think many women do. I find her books quite delightful and to introduce sex between her lovely heroines (in reduced circumstances but well born) and her wealthy, masculine heroes would be traitorous! Yours faithfully,

ANNE E. LIMEBEAR, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

This cover offers a hint of the sexual tension in Venetia

This cover offers a hint of the sexual tension in Venetia Another Heyer cover that does not do justice to the novel’s plot or brilliant humour.While there is no overt sex in any Heyer novel, there is plenty of sexual tension“one of the best descriptions of the Battle of Waterloo”

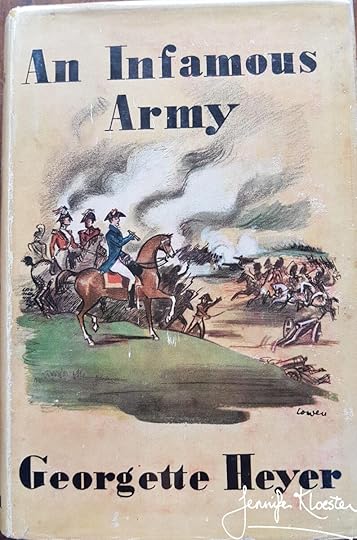

Another Heyer cover that does not do justice to the novel’s plot or brilliant humour.While there is no overt sex in any Heyer novel, there is plenty of sexual tension“one of the best descriptions of the Battle of Waterloo”Sir, As a bookseller for forty years I should like to support those who say that Georgette Heyer’s novels appeal to “educated people”. And when books were out of print after the last war we had to obtain a copy of “The Infamous Army” [sic] for the late Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart who wanted to give it to our Embassy in Brussels as it was, he said, “one of the best descriptions of the Battle of Waterloo”. Yours faithfully,

J. CHAUNDLER, The Blackdown Bookshop Ltd., letter, The Times, 6 October 1970

Sir Robert Bruce LockhartPhoto: National Portrait Gallery UK

Sir Robert Bruce LockhartPhoto: National Portrait Gallery UK An Infamous Army was an outstanding achievement.“Miss Heyer provides a beautifully written novel”

An Infamous Army was an outstanding achievement.“Miss Heyer provides a beautifully written novel”Sir, Marghanita Laski, and your correspondents all miss the secret of Georgette Heyer’s appeal to the middle-aged housewife. We don’t want works of art for our escapism, we don’t want emotion or facts of life of any description—we are surfeited with crying children, tired husbands, putting on weight and wearing a smile. What we want, and what Miss Heyer provides, is a beautifully written novel with a neat plot, witty dialogue and good characterisation, in a romantic world where the girl captivates the hitherto unattainable hero and is in consequence looked after, considered and protected to the hilt in a way that almost never happens in real life! Yours faithfully,

SUSAN HORSLEY, letter, The Times, 7 October 1970

Georgette was delighted by the letters she received defending her against Laski’s attack.

Georgette was delighted by the letters she received defending her against Laski’s attack. Lucy Boston wrote a letter of appreciation to Georgette in response to the Laski articleA letter from Lucy Boston

Lucy Boston wrote a letter of appreciation to Georgette in response to the Laski articleA letter from Lucy BostonDear Georgette,

As you know, I don’t often send you fan letters, but I think you should see this one from Lucy Boston, who is a distinguished children’s author of ours, as I think it might give you some pleasure.

Yours ever, Max Reinhardt

Max Reinhardt to Georgette Heyer, letter, 6 October 1970

Georgette wrote two letters to Lucy Boston, but sadly neither author kept the other’s correspondence, so we will never know what they actually said to each other. That it was complimentary in both directions is certain and in the end Georgette had only one thing to say on the matter:

The final word from GeorgetteYes, wasn’t the correspondence fun? I’ve had lots of letters like Lucy Boston’s and one Fan has actually written to the Laski, telling her where she gets off!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 11 October 1970

July 8, 2022

Charity Girl – against the odds part 2

The Times official logo. Wikimedia Commons.“I’m writing to ask you a favour”

The Times official logo. Wikimedia Commons.“I’m writing to ask you a favour”Dear Mrs. Rougier, I’m writing to ask you a favour. I wonder if you would consider waiving your quite reasonable distaste for being photographed and allow me to send a photographer from The Times at some point in the next two or three weeks. As you probably know, Marghanita Laski is a great admirer of your work and is going to write for me a lead piece on Charity Girl and its predecessors on October 1. It would give me great pleasure to publish with this review a fine new photograph of the author. We could make our choice from a number of pictures and I think I can promise you that we should do it most carefully since our aim will be to complement the notice with the portrait. I fully understand your reticence, particularly since we “Quality” newspapers have not exactly devoted a vast amount of space to your work in the past few years, but we do promise to make amends on this occasion and Marghanita is doing her homework very thoroughly. I shall be delighted if I can persuade you.

Yours sincerely,

J. Michael Ratcliffe, Literary Editor, The Times, letter to Georgette Heyer, 4 September 1970

Georgette’s husband Ronald encouraged her to be photographed by The Times

Georgette’s husband Ronald encouraged her to be photographed by The Times Georgette’s publisher at The Bodley Head was her adored friend, Max Reinhardt“Ronald has persuaded me”

Georgette’s publisher at The Bodley Head was her adored friend, Max Reinhardt“Ronald has persuaded me”It was a flattering letter, but Georgette was not keen. She was by now a huge international bestseller. Apart from the six novels she had herself suppressed, all of her books were still in print and her sales numbered in the millions. By the mid-sixties she had become a household name and her fans eagerly awaited their annual “Georgette Heyer” novel – hounding their booksellers if it did not appear. Charity Girl was to be Georgette’s fifty-fourth novel, and even before publication the subscription was enormous. It is not surprising that The Times wished to do a piece about her. Although she would not consent to an interview, Ronald eventually persuaded her to agree to be photographed. Georgette wrote to her adored publisher, Max Reinhardt to ask:

Darling Max,

Did you have anything to do with the enclosed request? As I’ve told Mr Ratcliffe, my first impulse was to write and tell him I’m just off to the South Pole, but Ronald has persuaded me to give way. He says I really must be photographed just once more, or there won’t be a photograph for my obituary notice! So I’ve asked Ratcliffe to ring me up next Wednesday morning, to fix a date. Not that I think our flat at all a suitable place for indoor photography, but that’s his worry!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 9 September 1970

1970 The last formal photo taken of Georgette Heyer.

1970 The last formal photo taken of Georgette Heyer. Reinhardt assured her that he had had nothing to do with the proposal but nevertheless was pleased that Georgette had agreed to be photographed. In due course the fateful day came and the Times photographer arrived at Flat 4, 60 Jermyn Street to find Georgette at her imperious best. She had dressed for the occasion in a well-cut skirt and jacket with her hair coiffed and a four-strand necklace of natural pearls around her neck. This last-ever formal photograph would see Georgette sitting with perfect posture in a straight-backed chair, a sceptical lift to her brows and – if one looks closely – the faintest hint of a smile. Behind her is a large bookcase crowded with reference books and at least one visible title is The Age of Napoleon by J. Christopher Herold, published in 1963. There is not a single one of her own books to be seen on any shelf. Although Ratcliffe as literary editor had promised her that “We could make our choice from a number of pictures and I think I can promise you that we should do it most carefully since our aim will be to complement the notice with the portrait”, Georgette did not see the photographs until the one chosen by The Times appeared in the paper.

Marghanita Laski. Her 1970 article about Georgette raised a storm of protest.

Marghanita Laski. Her 1970 article about Georgette raised a storm of protest.Photo: the National Portrait Gallery, LondonMarghanita Laski

Marghanita Laski was born in Manchester to a prominent family of writers and intellectuals. Her father was a judge and her grandfather the famous British scholar, linguist and Zionist, Moses Gaster. She had a first-class education, and attended Somerville College, Oxford, where she studied English. Marghanita met her husband-to-be, John Eldred Howard while she was at Oxford. Married in 1937, she had two children, before commencing her writing career in the early 1940s. Her first novel was published in 1944 and over the next thirty years she wrote novels, plays, short stories, screenplays, and in the 1960s and 70s produced biographies of Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling, George Eliot and Charlotte Yonge. Laski was also a major contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary. By 1986, she had added some 250,000 quotations to the dictionary making her “the supreme contributor, male or female, to the OED”. A clever writer and intellectual, in the 1950s and 60s Laski was a panellist on several popular BBC panel shows and she also worked as a columnist and critic. By the time of her death in 1988, she had more than two dozen publications to her name; today most of these have disappeared from view. After her disparaging article about Heyer appeared in The Times Georgette’s agent, Joyce Weiner, told her that she had “known M. Laski since they were both girls” and “that she is consumed by jealousy!” We will never know what prompted Marghanita Laski to write as she did – but her article raised a storm of protest from readers, so many of whom wrote to The Times that, after publishing several of them, the editor had to declare the matter closed.

The 1970 Bodley Head edition of Charity Girl. Marghanita Laski’s was meant to be a “lead piece” about the book and its predecessors.“The Appeal of Georgette Heyer” by Marghanita Laski

The 1970 Bodley Head edition of Charity Girl. Marghanita Laski’s was meant to be a “lead piece” about the book and its predecessors.“The Appeal of Georgette Heyer” by Marghanita LaskiOn 1 October 1970 Georgette Heyer’s new novel, Charity Girl, was published to an eager audience. On that same day, The Times published Georgette’s photograph beside Marghanita Laski’s article under the promising title “The Appeal of Georgette Heyer”. The title was deceptive. Although Michael Ratcliffe had promised that the paper would “make amends on this occasion” and that “Marghanita is doing her homework very thoroughly”, Laski’s article was, as Jane Aiken Hodge aptly described it, “a four-column sneer at once at the books, their readers and, by implication, their author.” Reading the article today, one cannot help but wonder at Ratcliffe’s assertion that “Marghanita Laski is a great admirer of your work”. Given the persuasions offered to Georgette by the Times’ editor in order to have her agree to be photographed, the article must have come as something of a shock. Here is the article quoted in full with my interpolations in bold between the paragraphs:

Ever since the serious novel deprived itself of the pleasure of the shapely story satisfactorily resolved, serious but compulsive novel readers who need the shapely story as a drug have had to turn, for this part of their need to the popular novel. Often it is easy to see why such books appeal to both non-intellectual and to intellectual: the gratifications to be gained from many thrillers, detective stories, science fictions and, of course, from Hornblower, are easy to discern. The Regency novels of Georgette Heyer constitute another and more difficult case. Their appeal to simple females of all ages is readily comprehensible. But why, alone among popular novels hardly read except by women, have these become something of a cult for many well-educated middle-aged women who read serious novels too?

One cannot but wonder at this continuing need by critics to denigrate “the popular novel”. Why is there an innate (and illogical) assumption that “popular” cannot equal good, worthy, well-written, or literary? What does Laski mean by non-intellectual? Is she suggesting that these readers are stupid? What is a non-intellectual and who and what distinguishes them from the intellectual reader? Laski’s tone is patronising and sexist. Her denigration of so-called “simple females of all ages” is extraordinary and incendiary.

For men, a brief description may be helpful. Among other books, including detective stories, Georgette Heyer has for some 40 years been producing novels set in a kind of Zinkeisen-Regency England of which the latest, Charity Girl, is published today. They are entirely concerned with love and marriage among an upper class that ranges from wealthy dukes to wealthy squirearchy. The heroes, usually demoniac, but occasionally gentle, are invariably dandies. The heroines may be spirited and sophisticated, spirited and naïve, or, increasingly of recent years, common-sensible. By miscomprehension and misadventure, hero and heroine fail to achieve mutual understanding until the end.

Incredible that Laski feels the need to “mansplain” – to MEN – here! So far from “doing her homework very thoroughly” it is clear that Laski has no clue about Heyer’s readership and is ignorant of the fact that, from her earliest books and right up to the time of this article, Heyer was read by both men and women of all ages and classes. Her comparison of Heyer’s Regency England to the work of the famous theatrical and film designer, Doris Zinkeisen, is not meant as a compliment. Zinkeisen was a brilliant designer renowned for her “flair” and “fantastic treatment” in creating wonderful costumes for the stage and screen. Laski’s apparent take on Heyer’s Regency World is that it is nothing more than its creator’s fantasy. As for Laski’s comment that her Heyeroes are “usually demoniac” and “invariably dandies” one can only wonder whether she had actually read more than a handful of Heyer novels. She certainly can’t have read Charity Girl whose hero is decidedly NOT demoniac!

Since nothing but the Regency element distinguishes these books from the best of the many thousands that used to fill the “B” shelves in Boots’ Booklovers Library, it must be this element that gives the stories their special appeal, and this element is very odd indeed, for Miss Heyer’s Regency England is not much like anything one infers about that time and place from more reliable writings, whether fiction or fact.

Really? Laski seriously can find nothing but the “Regency element” to distinguish Heyer’s novels from any others? She must have missed the wit, the humour, the brilliant dialogue, the flesh-and-blood characters, the compelling plots, the imbroglio endings, the historical detail, the meticulous research, the sparkle, the joy and the delight that make Georgette Heyer’s novels favourite re-reads for millions of people. Perhaps it is a good thing that Ms Laski is not alive to see the huge and lasting appeal of the Regency genre that Georgette Heyer created. If she were, she would undoubtedly marvel at the apparently insatiable appetite for Regency-set stories – whether they be books, films or television series such as Bridgerton. It is impossible to know what Ms Laski may have inferred from “more reliable writings” about the Regency – but she has clearly missed the wealth of accurate historical detail in Heyer’s 26 Regency novels!

That Miss Heyer has done a lot of work in the period is obvious. Any of her characters may talk more “Regency English” in a paragraph than is spoken in Jane Austen’s entire corpus. Real people often appear, such as Beau Brummel [sic] and Lord Alvanley and, of course, Lady Jersey, since whether or not the heroine will be admitted to Almack’s is often a grave crux—she always is. Any individual Heyer novel can be an extremely enjoyable pastime, but the more Heyer novels one reads the more one recognizes the same limited props, slightly rearranged on the stage. Smart chairs are covered in straw-coloured satin, smart gloves of York tan are negligently pulled on, buttered lobsters are toyed with at elegant meals. Hardly a hero but has a multi-caped coat tailored by Weston, is envied by young cubs for his mastery of the neckcloth. Hardly a dashing heroine but takes the ribbons of a phaeton. Hardly a novel but introduces a Tiger or Game Chicken to exemplify the language of the Fancy in which Miss Heyer is especially deft.

It’s nice that Laski notes Heyer’s “work in the period” (albeit in a condescending tone) and true that there is more cant than ever appeared in an Austen novel. Of course, the two authors were doing very different things. While a good critic may indeed compare Georgette Heyer to Jane Austen – especially given that the former drew inspiration from the latter and repeatedly pays homage to Austen in her novels – one does become tired of those who delight in pointing out that Jane Austen did not explain to her readers those things which would have been OBVIOUS TO THEM! As has been repeatedly stated by better-informed critics: Austen was writing contemporary fiction for people who already knew and understood her world because they were living in it; Heyer is writing historical fiction for readers who live and dress very differently from the characters in her novels. As for the claim of limited props, and there being “a Tiger or Game Chicken” in every novel, never mind that apparently almost EVERY heroine is dashing and can handle the ribbons in form (actually only 4 out of 26), it seems safe to conclude that Ms Laski has in fact read very few Heyer Regencies.

But those aspects of life on which Miss Heyer is so dependent for her creation of atmosphere are just those which Jane Austen (and other novelists for years to come) referred to only when she wanted to show that a character was vulgar or ridiculous. Food, clothing, furnishings, transport—it is because those matters engrossed a Lydia Bennet, a John Thorpe, a Mrs Elton, that we know them to be morally and socially worthless. Though Jane Austen’s letters show how greatly clothes and furnishings, at least, interested her personally, it would obviously be entirely improper for them to interest her in relation to commendable characters. It is possible, even probably, that Fitzwilliam Darcy wore a many-caped coat built by Weston; it is unthinkable that we should know that he did..

The only thing to add to my response above is to say that Georgette Heyer knew very well how to use food or clothing or transport to reflect a character’s moral or social worth. The scene in The Grand Sophy where Eugenia begs “to be allowed to take the back seat” of the landaulet and Cecilia instantly insists “that she should not” is just one of myriad examples in Heyerdom. In a single sentence she tells the reader something important about each young female’s character: in “begging to be allowed to take the back seat” of the landaulet Heyer shows us Miss Wraxton’s innate sense of moral superiority as manifested in this self-conscious act of apparent sacrifice, while Cecilia, seeing through Eugenia’s pseudo-piety, is equally determined that she – and not her brother’s unlikeable fiancée – will be the one to secure the least comfortable seat in the carriage and thereby baulk Eugenia’s attempt at martyrdom. It is worth noting here, that more than halfway through her article, Laski still has not written specifically about Charity Girl or its predecessors.

It is not, then, in respect of decorum that Jane Austen has influenced Georgette Heyer but the influence is there, at least in the early books, in some balance and turn of sentences: “We talked of all manner of things until I was comfortable again, and I do not think there was never [sic] anyone more good-natured”—There is certainly an echo of Harriet Smith here. But “her characters was no use! They was only just like people you run across every day”, as Kipling’s soldier said of Jane Austen; they are several social steps below Miss Heyer’s chosen ambience, and infinitely less glamorous. A model nearer in feeling and event would be Fanny Burney’s much earlier Evelina. But not there, or in Jane Austen or Maria Edgeworth or even Harriet Wilson does one find Miss Heyer’s extraordinary dandified heroes. There were dandies, but they were jokes, not heroes. Is it the shade of Sir Percy Blakeney that knocks at Miss Heyer’s door? If so, his shadow is the only one that falls on this pseudo-Regency in which there is almost no dirt, no poverty, no religion, no politics (a short step to silence in books for women). I have still got no nearer to discovering why Miss Heyer’s books appeal to so many educated women, but I know what lack of shadow it is that makes them of only limited appeal for me. It is because they have no sex in them.

The first part of this convoluted paragraph offers some small acknowledgement of the effect of Austen on Heyer, but why bring Kipling into it? Here again, Laski demonstrates her ignorance of Heyer’s oeuvre. One has only to read Bath Tangle for politics; Arabella for dirt and poverty; Cotillion for religion, and Venetia for superb sexual tension. Clergymen loom large in Austen’s novels and they play vital roles in most of her stories; Heyer uses clergymen and religion differently, but it is there for those who have the wit to see. As for the “extraordinary dandified heroes” one can only wonder at Laski’s meaning. While some of Heyer’s heroes have things in common and several are indeed dandies, no two are the same, and some are not particularly interested in clothes and certainly not in turning out in “prime style” (Miles Calverleigh or Hugo Darracott anyone?).

Now I realize that the popular romantic novel must be without overt sex, especially if it is to sell in tat holy of holies of the trade, Irish convents. [Okay, I really have to cut in here – WHAT is she talking about? Since when does the publishing industry rely on selling novels to Irish convents?] But not to say anything nasty is not necessarily the same thing as not to imply that sexual drive exists. In a good popular novel, be it overtly as clean as a whistle, we should never doubt that to put in the dirty bits would be merely to expand it and not to alter it or, as it would be in Miss Heyer’s case, to shatter it. We have never doubted the sexual passion that linked Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney throughout their alienation. Stanley Weyman’s depressed heroes suffer from real lust, his heroines are in danger of real rape. Even for Charlotte Yonge the sexual relations of her characters were at least implicit (and for what can be achieved within reticence, try her historical novel Love and Life). A counter-bowdlerizing expansion could be undertaken on any lastingly worthwhile popular novelist.

Needless to say, Ms Laski has NOT read Venetia! Or The Masqueraders, or These Old Shades, or Devil’s Cub, or Faro’s Daughter, or The Corinthian, or…

But if Miss Heyer’s heroines lifted their worked muslin skirts, if ever her heroic dandies unbuttoned their daytime pantaloons, underneath would be only sewn-up rag dolls. Her mariages blancs could run till doomsday without either partner displaying nervous strain; her heroes can, as in this latest, roam the country with unprotected young girls who need never fear loss of more than a good name. Certainly the odd hero may have had his opera dancer before he enters the heroine’s (and our) ken, but not inside these covers. So long as the puppets are out of their box, a universal blandness covers all.

I do have to chuckle a little bit here because, despite promising to do her homework, Laski seems oblivious to the fact that Georgette Heyer began writing bestselling novels in 1919 when she was only seventeen. Until 1960, her career spanned an era when, even if she had wanted to, Heyer would not have been allowed – either by her family or the state – to write overtly about sex. Prior to Penguin Books winning the 1960 court case over D.H. Lawrence’s sexually graphic novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, frank descriptions of sex in novels were taboo in Britain. By 1960, Heyer had been published for fifty years and was not suddenly going to change her phenomenally successful writing style to include scenes that would take her readers past the bedroom door. Heyer was also aware of the very real constraints imposed by the realities of her chosen historical period. While illicit sex certainly happened, it did not usually happen between young unmarried upper-class women and their potential suitors.

As for the “universal blandness” remark, nothing could be further from the reality of reading a Georgette Heyer novel.

Were we to take Georgette Heyer simply as a novelist for women whose only novel-reading was popular romance, she would deserve the highest praise. As the genre goes, her books are better than most, and more complicated; it often takes a couple of chapters to guess who will finally marry whom. The Regency element is pleasantly novel and the props, if limited, are genuinely period pieces. But the appeal to educated women who read other kinds of novels remains totally mysterious unless—is it?—could it be?—these dandified rakes, these dashing misses, the wealth, the daintiness, the carefree merriment, the classiness, perhaps even the sexlessness, are their dream world too?

Not much of a fan of the female reader was Marghanita Laski! Her patronising tone and extraordinary condescension – both to Heyer and to her female readers (she did not see fit to acknowledge Heyer’s male readers) – merely supports Joyce Weiner’s assertion that Laski “is consumed by jealousy”. Perhaps this was true. Certainly, Laski’s novels had never achieved the enormous success that Georgette Heyer had always enjoyed.

It was not the promised article and it most definitely was not a review of Charity Girl, and although upon reading it Georgette declared her “withers wholly unwrung” , it must have stung. There was a little more to come, however, in the form of outraged letters of protest to The Times from her fans… (next week)

Marghanita Laski, “The Appeal of Georgette Heyer”, The Times, 1 October 1970

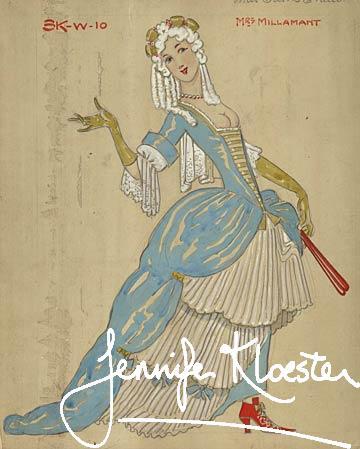

Doris Zinkeinsen’s sketch for Dame Edith Evans in the role of Mrs Millamant photo: Wikimedia Commons

Doris Zinkeinsen’s sketch for Dame Edith Evans in the role of Mrs Millamant photo: Wikimedia Commons Doris Zinkeisen by Harold Cazneaux photo: Wikimedia Commons

Doris Zinkeisen by Harold Cazneaux photo: Wikimedia Commons

June 17, 2022

Charity Girl – against the odds – part 1

As you will see by my use of the typewriter, I am busily engaged on my new book. There is no room to write at my desk once I’ve set up the Infernal Machine! I am now midway through the third chapter, and am – contrary to my expectations – Quite Enjoying Myself! I don’t think it’s too bad – in fact, I think that what I’ve done is Quite Good! Anyway, it is – to judge by Ronald’s chuckles! – quite amusing!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 8 November 1969

Barbosa’s delightful cover for Charity Girl – the design was Georgette’s suggestionA huge bestseller

Barbosa’s delightful cover for Charity Girl – the design was Georgette’s suggestionA huge bestsellerBy 1969, Georgette Heyer was a household name. Her birthday was listed in the Times and her previous two novels: Black Sheep and Cousin Kate had each sold more than 60,000 copies in hardback in the first two months of publication. With her ever-increasing success also came an increasing number of letters from fans, along with an increasing number of requests for interviews, invitations to special events and requests for her to speak at various literary functions. In February 1969 she turned down an invitation from PEN to be Guest of Honour at a sherry-party in Edinburgh, holding to her lifelong rule that “I never make Public Appearances”. It was a rule that sometimes caused her a pang of regret – especially later in her life. However, she had no wish to attend a sherry-party with herself as the focus of attention. Despite her immense success as a writer, Georgette Heyer had no desire to be in the spotlight, preferring instead to live privately and securely behind the mask of “Mrs Ronald Rougier”. As her son Richard explained, she was not only intensely shy but she could also see no reason for anyone to be interested in her but only in her books. It was because of this that she asked her publisher’s secretary, the kind and efficient Belinda McGill, to reply to the Scottish arm of PEN on her behalf:

If you can refuse for me, without giving Grave Offence, I shall be Everlastingly Grateful to you! You could say (with almost complete truth) that I never make Public appearances; you could say (with COMPLETE truth) that since I refused, many years ago, to attend an English PEN club luncheon, I feel it would be most invidious of me to go to a sherry-party thrown by the Scottish Centre of the International PEN; you could say that I regard my Scottish holidays as Complete Escapes from my Literary Life; you could say that Miss Heyer has no desire to figure as a Guest of Honour at this or any other party

Georgette Heyer to Belinda McGill, letter, 6 February 1969

Though practically inconceivable in today’s publishing world, Georgette’s refusal to engage in personal publicity did not harm her sales. The money was rolling in and, with the Booker deal behind her, for the first time since her father’s death in 1925, she had allowed herself to completely relax – to the point of taking an entire year off from writing. She had written nothing since finishing Cousin Kate in April 1968 and months later told her publisher “I am enjoying my idle year”. 1969 would prove to be one of Georgette’s rare years without a book. It had been the Booker Brothers deal that had finally relieved her mind of financial worry. For the first time in her long career the absence of the “annual Heyer” was not due to a loved one’s death, her own poor health, or to War. This time she took a year off simply because she wanted to. Perhaps we should be grateful that Georgette Heyer worried over money as much as she did, because without that pressure (real or perceived) she may never have written so many enduring bestsellers!

Georgette loved seeing the famous Icelandic waterfall Gullfoss. Photo: AEVAR GUDMUNDSSON Wikimedia CommonsHolidays and a new book…

Georgette loved seeing the famous Icelandic waterfall Gullfoss. Photo: AEVAR GUDMUNDSSON Wikimedia CommonsHolidays and a new book…IHer “idle year” was to end in August when she and Ronald were to go to Scotland as usual. This time they were to stay at the famous Gleneagles Hotel (which they did not like) and the Marine Hotel (which they did) while Greywalls underwent renovations. However, before that holiday took place, they were to go to Iceland. It was Ronald’s wish to see that beautiful country and he had convinced Georgette to accompany him. On the 8th July 1969 they left for Iceland for a fortnight’s holiday. She had enjoyed their last Scandinavian holiday and she found Iceland to be “a fantastic country – like nothing I’ve ever seen or dreamt of”. She loved the magnificent scenery and the bracing Icelandic air and told friends “I shall always be glad I’ve seen it'”. The Iceland trip proved to be exactly what she needed after suffering from another “ghastly throat” in the spring. The truth was that Georgette’s health had been indifferent for some time. She had been beset by various ailments, all of which had taken their toll on her both physically and mentally. Iceland did her good, however, and on her return she made a conscious decision to begin writing a new book once they had returned from Scotland.

The Marine Hotel East Lothian. Georgette loved staying in the tower room with its views of the Bass Rock and the firth beyond. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Marine Hotel East Lothian. Georgette loved staying in the tower room with its views of the Bass Rock and the firth beyond. Photo: Wikimedia Commons The vast Gleneagles Hotel in Scotland. It did not suit Georgette and Ronald who were used to the more cosy and less touristy surrounds of Greywalls. Photo: Wikimedia Commons“The thing to do is to start writing the book”