Jennifer Kloester's Blog, page 8

July 31, 2020

1932 – Footsteps in the Dark – the first detective-thriller

In April 1930 Georgette Heyer had returned to England from Macedonia where her husband, Ronald Rougier, had been working as a mining engineer in the lead mines near the Bulgarian border. It cannot have been an altogether easy transition, as they had no home of their own in England and jobs for mining engineers were not easy to find once back in Britain. They had returned home in part because Georgette had decided that they should try for a baby which, for her atleast, meant no more overseas postings. As she explained to her friend Carola Oman, if she was going to have a baby then she wanted to have it in England. Once home, the Rougiers lived at 62 Stanhope Gardens for some months and Ronald invested in a partnership in a gas, light and coke company in the Horseferry Road. Unfortunately, the investment did not reap the hoped-for rewards and by October they had decided to leave London and move to the country. It was there that she would write her first detective-thriller, Footsteps in the Dark.

The dustjacket of the1934 reprint of Footsteps in the Dark had the same picture as the 1932 first edition but with the addition of the Longman triangle.

The dustjacket of the1934 reprint of Footsteps in the Dark had the same picture as the 1932 first edition but with the addition of the Longman triangle.A penchant for privacy

Perhaps it was her penchant for privacy that made the idea of country living so appealing to Georgette. Her father’s death in 1925 had been a cataclysmic event in her life and her overwhelming grief had kept her from writing for over two years. It was during her time in Tanganyika that she had healed. Isolated from the world back home and from the countless reminders of her loss, living a grass hut in a remote compound, the only expatriate woman for 150 miles, she had begun writing again. And then in Macedonia she had lived in a small medieval village, happy to write without the interruption of a busy social life or chatty neighburs (she didn’t speak the language). As an author, she was used to isolation, but even outside of her writing life, Georgette did not seek the bright lights and and busy social whirl of London. By April 1931, Georgette and Ronald had decided to move to Sussex.

A map showing Horsham and the surrounding villages and hamlets where Georgette Heyer lived and set some of her novels.

A map showing Horsham and the surrounding villages and hamlets where Georgette Heyer lived and set some of her novels.A new home in Sussex

Georgette had happy memories of childhood holidays spent in Sussex visiting her grandparents and this may have been a factor in their choosing Sussex as the county in which to find their new home. She had finished writing her remarkable medieval novel, The Conqueror, in 1930 and by the time of its publication in March 1931 she and Ronald had settled on Horsham as the place for Ronald’s new business venture. He had bought a lease for the Russell Hillsdon sports store at Number 9 the Bishopric in the centre of Horsham – at that time a large market town. There he would restring tennis racquets, mend guns and assist members of the local golf club (Ronald also joined Mannings Heath Golf Club), while Georgette wrote her books and helped to support them financially. The Rougiers left for Sussex on the last day of April 1931 without knowing quite where they were going to live. In September, Georgette wrote to her agent, Leonard Moore, from Swan Ken – a house in Broadbridge Heath about two miles west of Horsham. She wrote to tell him that she was writing a serial story and that she hoped he would find a publisher for it:

‘Well, what price my serial story? I may as well tell you (since I feel sure no one else will) that it’s developing into a remarkably fine effort. I haven’t the smallest hope that any editor will take it, but Gosh, if one did how opportune it would be!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, 4 September 1931

Ronald’s shop at Number 9 the Bishopric, Horsham is now a menswear store.

Ronald’s shop at Number 9 the Bishopric, Horsham is now a menswear store.“I MUST HAVE MONEY”

Footsteps in the Dark was the intended serial but in the end the story would be published as a novel. Longmans, who had published Heyer’s contemporary fiction since Helen in 1928, offered Georgette an advance of £200. She signed the contract on 13 November for, as she ecstatically told Moore:

We are expecting an addition to the family in February – to my almost insane rapture…This, you see, accounts for my frenzied energy in writing this blasted thriler. I MUST HAVE MONEY. Like that. All in capitals. I pray to god to soften the hearts of an editor unbusinesslike enough to pay me an extortionate sum for the privilege of producing the thriller.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 4 September 1931.

Hugely popular

The detective-thriller had become hugely popular by the 1920s and 30s, thanks largely to the writings of Edgar Wallace, whose novels, including The Four Just Men, The Mind of Mr J.G. Reeder and The Ringer, sold in millions. Georgette’s first ‘thriller’ Footsteps in the Dark, was inspired by the ghostly footsteps which she and Ronald had sometimes heard in their house in Kratovo in Macedonia. The novel was typical of the genre and, as a first attempt at a murder mystery and a kind of modern Gothic novel, Footsteps in the Dark is a fair effort that, ninety years later, remains readable. It is a lightweight story set in an old manor house in the English countryside not too far from London. The house has been inherited by a brother and sister and they and their spouses, along with their scatty older aunt (a forerunner of some of Heyer’s later scatty but intelligent older women) have taken up residence there. They are soon beset by ghostly noises, strange footsteps, a skeleton, a drug-crazed French artist, an eclectic set of neighbours, a mysterious stranger, a bumbling local policeman and murder. The dialogue is very 1930’s English with a touch of Wodehouse and is very much of its time.

The wonderful 1934 cover for the first book in the set of four uniform editions of Longmans’ “A Murder Mystery by Georgette Heyer” series.

The wonderful 1934 cover for the first book in the set of four uniform editions of Longmans’ “A Murder Mystery by Georgette Heyer” series.12,000 copies sold

While Footsteps in the Dark is not Heyer at her best, it remains a pleasant and entertaining story and parts of it are great fun. She was still learning her craft and this new departure from her earlier books would mark the beginning of a series of murder mysteries in both her contemporary and her historical fiction. While the musrder mystery would not prove to be her forte (although The Talisman Ring is a marvellous witty murder mystery) there was something about the mystery that appealed to Heyer. Her son once explained that she regarded writing thrillers ‘rather as one would regard tackling a crossword puzzle–an intellectual diversion before the harder tasks of life have to be faced’. Georgette definitely enjoyed writing Footsteps in the Dark and was delighted when the novel sold 5000 copies in its first three months earning out her advance. Within a year it had sold nearly 12,000 copies and earned her an additional and very useful £800.

The 19343 Longmans reprint

The 19343 Longmans reprint The 2006 Arrow edition

The 2006 Arrow editionA new son and a new book

On 12 February 1932, Georgette Heyer’s baby son, Richard George Rougier, was born on the same day that Footsteps in the Dark was published. A few days later she received a letter from Kenneth Potter of Longmans who hoped that the baby and Footsteps in the Dark ‘were going to be my two most successful works’. In typical Heyer style, some years later Georgette remembered that

‘This work, published simultaneously with my son on Feb. 12th 1932, was the first of my thrillers, and was perpetrated while I was, as any Regency character would have said, increasing. One husband and two ribald brothers all had fingers in it, and I do not claim it as a Major Work.’

Georgette Heyer

Richard George Rougier was born on the same day that Georgette Heyer’s first detective-thriller was published.

Richard George Rougier was born on the same day that Georgette Heyer’s first detective-thriller was published.

July 24, 2020

The Conqueror – a deep dive into history

Early in 1930, soon after she and Ronald returned to London from Macedonia, Georgette Heyer decided to take a deep dive into history and write her most serious historical novel to date. The book was to be The Conqueror – a retelling of the story of William the Conqueror from his birth in France in 1027 to his coronation in Westminster Abbey in 1066. It was a hugely ambitious project and one which would require an immense amount of research but Georgette was keen to try her hand at the sort of historical novel that her good friend Carola Oman was writing. Carola’s novel Crouchback had been published the previous year to good reviews and Georgette would eventually dedicate The Conqueror to her friend:

To CAROLA LENANTON

In friendship and appreciation of her own incomparable work

done in the historic manner dear to us both.

Georgette Heyer, The Conqueror, Heinemann 1931.

The 1931 first edition jacket of The Conqueror

The 1931 first edition jacket of The Conqueror Georgette signed this first edition copy to a Dr Wight but their connection is unknown

Georgette signed this first edition copy to a Dr Wight but their connection is unknownGeorgette immersed herself in the available sources and made good use, in particular, of J.R. Planché’s The Conqueror and his Companions (1874). The was beset with challenges and it is a testament to Heyer’s skill that she managed to corrall her material into such a lively, vivid novel. As well as depicting a large cast of historical characters – all of whom she researched throughly – she created a number of fictional characters so that her readers could “see” the characters, the action and the scenery. First among these is Raoul de Harcourt, who becomes William’s most loyal follower. It is Raoul’s determination to stay in the thick of things that enabled Georgette to describe so many historical scenes so vividly. Raoul also becomes the glass through which WIlliam the Conqueror is seen and measured for Raoul does not always approve of his master’s judgement or actions. Georgette also gave William a jester, ‘Galet’, a character undoubtedly inspired by the wise fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear and by Walter Scott’s fool, Wamba, in Ivanhoe. The cast of characters is large and complex and years later Georgette acknowledged some of the challenges she had faced in writing The Conqueror:

What a lot of work I put into it! And how difficult it was to correlate the various contemporary (and largely inaccurate) accounts of William’s Life and Times – a task not made easier by the fact that, at that date, hardly anyone had a surname, and that the Chroniclers bestowed Christian names in a somewhat haphazard way, Ralph de Toeni, for instance, appearing, indifferently, as Ralph, Raoul, Reynaud, and Richard! And, even worse, that awful Fitz, meaning “the son of.” All very well if the character was historically important, or if his father had an unusual name, such as Osbern; but although the student of the period knows All About William Fitzosbern, few could be expected to recognize William Fitzwilliam as his son. Well, not at a glance, anyway!

Georgette Heyer

Georgette and Ronald in France in 1930 during her research trip for

The Conqueror

.

Georgette and Ronald in France in 1930 during her research trip for

The Conqueror

.Determined to recreate the past as accurately as she could, Georgette and Ronald also travelled to Normandy to gather material for the book. It must have been a fascinating journey travelling about northern France, visiting the sites of William’s battles and sieges in order to gain a sense of the physical landscape and see the places which had born witness to so many of the Conqueror’s exploits. It is hard not to be impressed by Heyer’s grasp of her subject and of her ability to distill so much historical detail into a readable fictional account. From any point of view The Conqueror is a significant achievement.

The map printed inside the endpapers of the hardback editions of the novel.

The map printed inside the endpapers of the hardback editions of the novel.After reading widely on the subject, Georgette divided The Conqueror into five parts and took great care to reproduce the Norman and Saxon courts as vividly as she could without overwhelming her reader with slabs of historical detail. She also enlisted Ronald’s help – just as she had done with Beauvallet – and he proved very effective in finding bits of useful information with which she could flesh out the story and bring her characters to life. She later acknowledged her husband’s contribution to the book with one of her characteristic tributes on the flyleaf of hisfirst edition copy:

‘Here is THE CONQUEROR for Ronald, with acknowledgements for his watchfulness & care in all such matters as Bear-fights, Cavalry-charges, Distances, & Male-Etiquette and with love from George.’

Georgette Heyer, Dedication, The Conqueror, 1931.

The 1933 UK edition published by Heinemann

The 1933 UK edition published by Heinemann The 1966 US edition published by Dutton for the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings

The 1966 US edition published by Dutton for the 900th anniversary of the Battle of HastingsGeorgette finished The Conqueror late in 1930. It had not been an easy book to write, and halfway through she had felt a sudden anxiety about it, prompting a letter to her agent in April of that year in which she expressed some of her uncertainty:

I have finished Part II, 60,000 words perpetrated already. I shall have to cut it a bit, shan’t I? William has now married his Matilda, & I approach what I think is going to be the most difficult part of the five – “The Might of France” I don’t know what Heinemann will say. Sometimes I think I’ve written a book heavy as lead; at others I don’t think it’s so bad. Carola likes it; Joanna Cannan says it is the most interesting historical novel she has read, but I fear she is partial and prejudiced.

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, April 1930.

Her fears were unwarranted for The Conqueror was a decided success and Georgette soon earned out the £300 advance against royalties which she had received for the novel. In its first six years The Conqueror was reprinted eight times and thirty-five years later, the US publisher, Dutton, released the novel to mark the 900th anniversary of William the Conqueror’s successful invasion of England. The jacket must have pleased Georgette at least as much as the long review in Best Sellers which ended with a glowing account of her scholarship and skill:

Her novel is primarily valuable, however, not so much as a portrait of a man, as it is a period in the history of Western Europe. The Conqueror grew out of an incredible amount of historical research into the way of life, the way of speech, the way of thought, and feeling, and praying in the eleventh century. Without sacrificing the flow of her plot, Miss Heyer conveys an understanding of this period, more authentic as well as more colorful than many historical tomes. It is obvious in reading this novel that Georgette Heyer, who has previously published over 30 historical romances, is indeed mistress of her craft.

Genevieve M. Casey, Best Sellers, 15 November 1966, pp309-10.

July 17, 2020

Barren Corn – the fourth and final ‘modern’ novel

Georgette Heyer wrote her fourth and final modern novel while living in Kratovo, a small village in Macedonia. Barren Corn is the story of Laura Burton, an intelligent, lower-middle class woman from Brixton, and Hugh Salinger, a handsome, selfish member ‘of the Leisured Class’, who meet on the French Riviera one summer after the First World War. Against all her instincts and her better judgement, Laura is persuaded by Hugh to marry him. They have an idyllic honeymoon in Italy before unexpected news takes them home to England where the apparently mismatched couple must face the consequences of their decision. Barren Corn is Georgette’s most ambitious and compelling contemporary romance and the only one of her novels to deal directly with the issue of class in English society. From the beginning, Laura sees the class difference between herself and Hugh as insurmountable, whereas Hugh decides that he can change her – mould her into ‘a creature made perfect’, so that even his mother will ‘forget the accident of her birth.’

Published in April 1930, Georgette Heyer loathed the jacket design for Barren Corn.

Published in April 1930, Georgette Heyer loathed the jacket design for Barren Corn.Inspired by Swinburne

The title of the novel comes from a line in Felise, a poem written by the famous English Poet Algernon Swinburne. In the poem a man’s passionate love for Felise lasts only a year before it withers and dies and he must tell her that he no longer loves her. In Barren Corn, Hugh Salinger’s weak character is revealed through his continuing refusal to treat Laura honestly. In the novel Heyer has much to say about who really has ‘class’ and what it is that makes a person worthwhile. Laura’s struggle with the English class system, its repressive nature and damaging judgements have a profound effect on the young wife and the novel becomes a study in psychology as much as a story about a failed relationship.

Who knows what word were best to say?

For last year’s leaves lie dead and red

On this sweet day, in this sweet May,

And barren corn makes bitter bread.

What shall be said?

Algernon Swinburne, Felise.

A loving father

Georgette’s father, George Heyer, like many Oxbridge undergraduates of his day, was a great admirer of Algernon Swinburne’s poetry. Swinburne was enormously influential in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and it was he who invented the Roundel, a poetic form which George Heyer experimented with in his own poetry. George would have read Swinburne’s poems aloud to Georgette just as he read her Shakespeare, Dickens and the Renaissance poets. As a child Georgette actually met Swinburne, who used to walk daily from his home in Putney to Wimbledon where she lived. Felise is a sad poem and its influence permeates Georgette’s final contemporary novel.

The 1936 Longmans edition with its apposite quotation from the novel.

The 1936 Longmans edition with its apposite quotation from the novel.Rated high

Barren Corn is the only one of Georgette Heyer’s novels to examine deeply the psychology of an enduring, dedicated love – a love so strong as to be utterly self-sacrificing – albeit for the wrong reasons. It is an unusual book which could have made a gripping film and it caught the attention of several reviewers, including the American critic, Isabelle Wentworth Lawrence, who wrote regularly for the Boston Evening Transcript. She was much struck by Barren Corn, rating it high among Georgette’s novels:

The story is beautifully written, with that smooth precision of Miss Heyer’s which seems to be effortless. There is never a word too many. There is never a word too few. Underneath the somewhat cynical style with which she portrays England’s Ruling Order, runs the same compelling force which makes her historical romances so unusual, and fascinating.

The American edition of Barren Corn also published in 1930. To date, I have never seen the jacket.

The American edition of Barren Corn also published in 1930. To date, I have never seen the jacket.Snobbery & psychology

In some ways Barren Corn was a conduit through which Georgette finally gave voice to some of her thoughts about sex, religious beliefs about life after death and the problem of class in British society. It is a surprisingly empathetic novel and, whether she meant to or not, in telling Laura’s story Georgette demonstrated a deep understanding of aspects of the human psyche and the kinds of mental traps into which individuals can fall when driven by love or sexual desire. She sees clearly the great class divide and explores its bitter consequences for Hugh and Laura when they attempt to bridge the chasm of cultural and social difference that comes to lie between them after their marriage. By the end of the novel, her heroine finds herself in a kind of mental and emotional limbo – a personal hell from which there is no escape if she is to spare her own family pain and abide by the code of conduct laid down by her husband and his class. Barren Corn is as much about snobbery as it is about the worth of the individual, a point which Isabelle Wentworth Lawrence noted with some relish:

What gives it its distinction is that, hand in hand with the romance goes an astonishing outlook on society. The entire novel might be a treatise on socialism, were it not so aristocratic. The masses, to be sure, are disregarded, but the lower middle classes are painted, for all the horror of their gentility, as twice as good as you are, Gunga Din. Laura is worth six of Emmeline and all her like. Nevertheless she obviously gives Miss Heyer “the horrors”. She herself who admires her immensely, could not have lived with her long. Yet she makes us love and admire her.

Isabelle Wentworth Lawrence, Boston Evening Transcript, 27 September 1930, Books, p.3. quoted in Fahnestock-Thomas, Critical Retrospective, pp. 89-92.

The first edition dist jacket of a the novel given to her friend ‘Cassy’.

The first edition dist jacket of a the novel given to her friend ‘Cassy’. To Cassy, with much love from Georgette – who was Cassy?

To Cassy, with much love from Georgette – who was Cassy?“Nearly made me sick it up on the mat!”

Barren Corn came out in April 1930, a few months after Georgette and Ronald had returned to England from Macedonia. The year before, Longmans had bought from Hutchinson the rights to Georgette’s first contemporary novel, Instead of the Thorn, and had employed the well-known graphic artist Theyre Lee Elliott to design the cover for it and for the first edition of Pastel. The dustjacket for Pastel was particularly striking with a superb art-deco design in bold shades of orange, red and black, and it may have been the stark contrast in style and colour between this and the artwork selected for Barren Corn‘s cover which caused Georgette to write to her agent to protest at Longmans choice of jacket design for the new novel.

‘I never in my life saw a more – well, blood-stained wrapper! It nearly made me sick it up on the mat, so to speak. A chorus of universal disapproval has arisen from all who have seen it. What malign spirit of inartistry prompted the – so-called – artist to plonk that ghastly, that dire woman on the cover? If he’d contented himself with the mimosa on a black ground it mightn’t have been so bad. As it is – he ought to be put in a pot and boiled.’

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, 1930.

Another dustjacket which Georgette Heyer would have loathed. This is the 1938 Longmans cheap edition described as ‘A Love Story by Georgette Heyer’.

Another dustjacket which Georgette Heyer would have loathed. This is the 1938 Longmans cheap edition described as ‘A Love Story by Georgette Heyer’.Not to everyone’s taste…

Though not to everyone’s taste – and many readers dislike it intenseIy – I have read Barren Corn several times and am always struck by its strong psychological plot and sharply-executed characters. Georgette Heyer may have come to loathe the novel and to vehemently suppress it in the late 1930s but I think there is much to learn from her final contemporary book.

July 10, 2020

Beauvallet – a great adventure

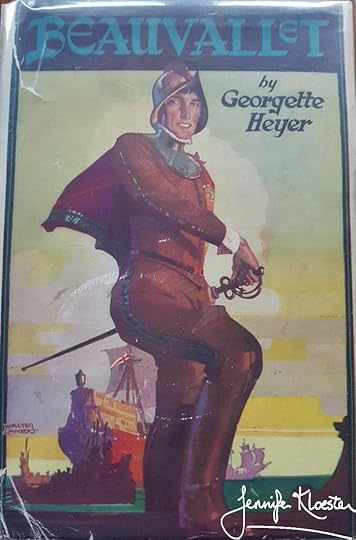

The first edition dustjacket. Heinemann published Beauvallet in September 1929 while Georgette was living in a village in Macedonia.

The first edition dustjacket. Heinemann published Beauvallet in September 1929 while Georgette was living in a village in Macedonia.Writing far from home (again)

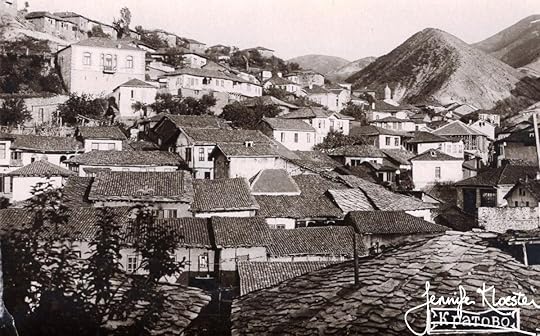

Georgette soon settled into life in Kratovo, the small village in Macedonia to which she and Ronald had moved in 1928 after their return from Africa. Their new home in Kratovo was an old Turkish house with a water supply that had been built in Roman times. Though not remote as their grass hut in Tanganyika, it was still a relatively simple life. While Ronald worked in the lead mines near the Bulgarian border, Georgette spent her days writing and reading. Her new book was to be a swashbuckling adventure story which she called Beauvallet. This would be her fourth historical romance for Heinemann and before leaving England for Macedonia she had rejoined the London Library so that she could still gain access to the books she needed for her research. The London Library had an overseas service and would send books to their members living in Europe. A ready supply of reference books enabled Georgette to continue writing the historical fiction that she loved. She was a conscientious writer who did her research with the aim of giving her readers a vivid (if somewhat superficial) sense of an era and even in her most light-hearted novels she was careful to go to the sources for the ephemeral detail that made even her earliest historical romances convincing.

Kratovo, where Georgette lived from 1928 to 1930 and where she wrote her sixth historical novel,

Beauvallet

. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kratovo,_North_Macedonia

Kratovo, where Georgette lived from 1928 to 1930 and where she wrote her sixth historical novel,

Beauvallet

. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kratovo,_North_MacedoniaAn adventurous spirit

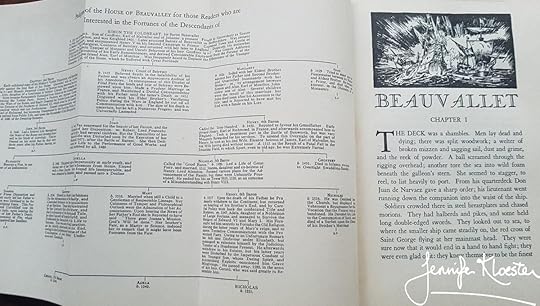

She had an adventurous spirit in those early years of her marriage which is reflected in the novel she wrote in Kratovo. Beauvallet is set during the reign of Elizabeth I, when England was in conflict with Spain and Sir Francis Drake ruled the seas. Another of Heyer’s swashbuckling adventure stories, it stars the captivating Sir Nicholas Beauvallet, a direct descendant of Simon Beauvallet, the hero of Georgette’s 1925 novel, Simon the Coldheart. She must have enjoyed writing Beauvallet for her pleasure is evident in the detailed and humorous family tree which she devised for the first edition of Beauvallet and which she headed: ‘Pedigree of the House of Beauvallet for those readers who are Interested in the Fortunes of the Descendants of Simon the Coldheart’. In it she offered her readers such entertaining tidbits as ‘Simon died of the Stone, which he Suffered with Great Fortitude’ and that he was ‘frequently heard to Deplore the Effeminacy of the Younger Generation’.

The fold-out family tree which appears in both the UK and USA first editions of

Beauvallet

.

The fold-out family tree which appears in both the UK and USA first editions of

Beauvallet

.El Beauvallet who bit his thumb at Spain!

Nicholas Beauvallet is one of Heyer’s vivid characters, whose many impossible feats become believable because the writing is so good. Known to the Spanish as ‘El Beauvallet’ and ‘Mad Nick’ to his men, he is a master swordsman, a pirate and a gentleman, with a sparkling sense of humour that sees him through all of his many adventures. A friend to Drake and a terror to the Spaniards, the story opens with ‘a bloody, ravaging tornado of a sea fight, in which a mighty galleon is badly beaten by a small English vessel.’ This small vessel is the Venture, Sir Nicholas’s own ship, with which he defeats the Spaniards and takes prisoner the beautiful Dominica and her father, a former Spanish governor of the West Indies. Of course, Sir Nicholas falls instantly in love with the lady and against all odds escorts her and her father back to Spain, promising to come for her within a year and take her back to England as his wife.

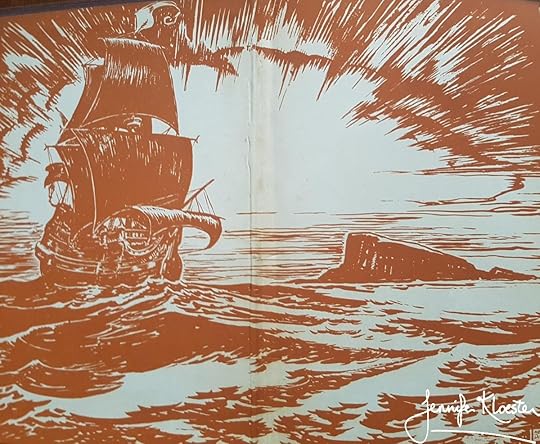

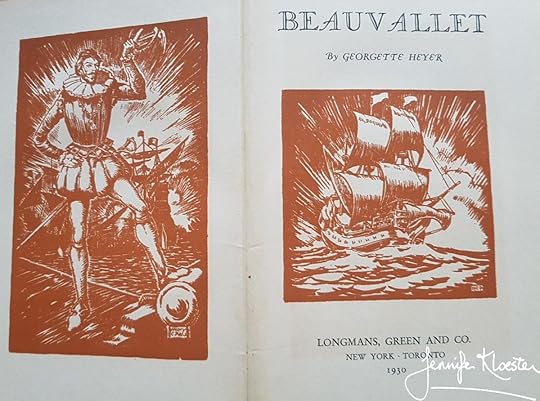

The endpaper and frontispiece of the American first edition of

Beauvallet

published in February1930.

The endpaper and frontispiece of the American first edition of

Beauvallet

published in February1930.The USA edition – doing Georgette proud

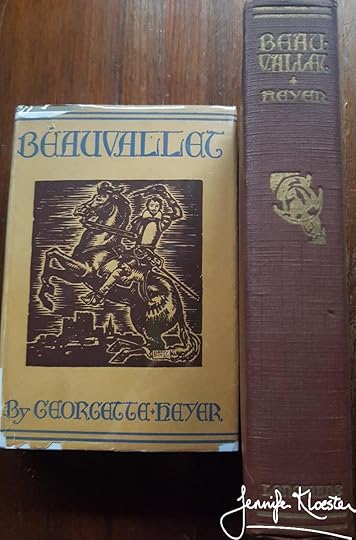

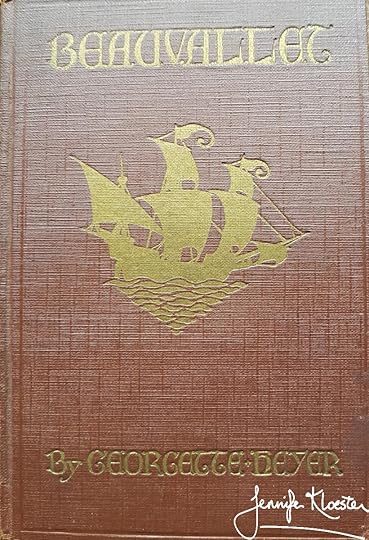

While Heinemann published an attractive edition in 1929, in the United States, Longmans did Georgette proud by producing a stunning edition of Beauvallet with endpapers of a ship in full sail and a facing title page with a picture of Sir Nick in Elizabethan dress and another picture of a ship on the title page. Longmans designed an elegant new cover with Beauvallet riding a rearing horse and also reproduced the fold-out family tree. A second, elegant brown-and-gilt edition also came out that year. Beauvallet received good reviews in America, with a glowing account of the novel in the Boston Evening Transcript:

‘For several years Georgette Heyer has been proving herself a master of romantic fancy-dress fiction. What she does is always right, always highly flavored of her period, so that in some odd fashion the whole era is actually alive before you, and that with few descriptions. It is so easy that you are assured of long study in preparation, while there is no faintest trace of effort.’

Isabelle Wentworth Lawrence, “Brave Knights and Beautiful Ladies. Georgette Heyer Writes a Novel of Swashbuckling Adventures in England and on the Spanish Main”, Boston Evening Transcript, 18 April 1930.

The American first edition, published in February 1930 by Longmans.

The American first edition, published in February 1930 by Longmans.  A different American first edition.The true American first edition with the dustjacket has beige coloured boards. This brown edition with the gilt sailing ship is also an American first edition. No dustjacket seen.

A different American first edition.The true American first edition with the dustjacket has beige coloured boards. This brown edition with the gilt sailing ship is also an American first edition. No dustjacket seen.Georgette enjoyed many aspects of her life in Macedonia: it was simpler and free of the demands of her extended family; she and Ronald were happy in each other’s company and they took walks together and sometimes went horseback riding around the district. Occasionally they would make the trip to the capital, Skopje, and there join other ‘Britishers’ for drinks or dinner. One night they to the local cinema in Kratovo, not to see a movie, but instead to see it burn down after the owner, having insured the building for a handsome sum, announced to the town that he would set it on fire and invited everyone to come and watch. The whole village turned out as if for a party and when the time came for the conflagration the police merely ensured that everyone was clear of the building and then stood back to watch with the crowd as the building went up in flames. Georgette later reported that the cinema owner had collected his money from the insurance company and that everyone had enjoyed a very good time! She did not have such a good time in the dentist’s chair, however. In fact, Georgette Heyer almost died in Kratovo when the gas line became blocked and she turned blue before the anaesthetist noticed the problem and fixed it. By the end of 1929, the Rougiers had decided it was time to go home, but not before Georgette had begun writing a new novel (more on that next week).

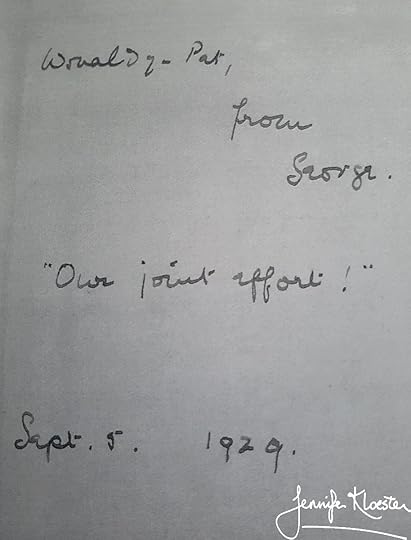

“Our joint effort!”

Ronald had a hand in Beauvallet, though whether he helped Georgette with the plot as he would in some of her later detective novels, or whether he assisted with research and the historical detail, is impossible to tell. That he took a continuing interest in his wife’s writing is clear. After their marriage and her father’s death, Ronald became Georgette’s first reader and critic. She valued his opinions and admired his knowledge of history as well as his ability to hunt up elusive facts or bits of ‘period colour’ which she could use in her writing. Living in Macedonia may have meant depending on Ronald more than usual for when the book came out she inscribed his copy of Beauvallet with an appropriate acknowledgment: ‘”To Wonaldy-pet, Our joint effort”‘ and signed herself ‘George’ – a name reserved for use by only her closest friends and relatives. Georgette and Ronald understood each other very well. Ronald’s practical support when she was writing books such as Beauvallet and laterThe Conqueror also meant that he had a legitimate stake in his wife’s work.

A great deal!

Georgette finished Beauvallet while in Macedonia and posted the manuscript home to her publisher in time for September publication. This was her fourth historical novel for Heinemann and this time they paid her an advance of £200 against royalties. She had received only a £50 advance for Simon the Coldheart and for The Masqueraders, so this fourfold advance was a clear indication of her steadily increasing sales and her growing reputation. As her career advanced, with each new novel her agent, L.P. Moore, had sought a bigger advance and better royalties. In 1929, with Beauvallet, he brokered terms which gave Georgette 15% on the first 3,000 copies sold, 20% on the next 7,000 copies and 25% on all copies sold above 10,000. These were remarkable terms that would be an author’s dream today! More than ninety years later, Beauvallet is still selling.

July 3, 2020

Georgette Heyer died on 4 July 1974 but her novels live on…

Tomorrow, 4 July 2020, will mark forty-six years since Georgette Heyer died from lung cancer in Guys Hospital, London. Int he days following her death several long obituaries were published in the major newspapers in Britain, including the Times, The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and The Sunday Telegraph and, in America, in The New York Times and Publishers Weekly.

Some of Georgette Heyer’s beloved historical novels.

Some of Georgette Heyer’s beloved historical novels.“Georgette Heyer’s Regency romance ends at 71”

With the publication of these tributes to Georgette Heyer, the public discovered for the first time that one of their favourite authors was actually Mrs Rougier, wife of Ronald Rougier QC, and the mother of rising barrister, Richard Rougier, who would later become a High Court Judge. The obituaries offered the first insight into the background of an author who, at the time of her death, was selling 100,000 copies of her novels in hardback and a million copies per title in paperback,. They each pointed out how, despite her enormous success, Georgette Heyer was unique in both wishing for, and maintaining, her personal privacy. To the world she was “Georgette Heyer”, beloved bestselling historical novelist and mistress of ironic comedies of manners; to her family and close circle of friends she was Georgette Rougier who liked nothing better than an intimate dinner party or a riotous game of bridge or a quiet holiday in Scotland. Some papers quoted from a letter she had once written to her agent:

‘I have no hobbies and play no ball-games. I belong to no societies and make no Personal Appearances.

Georgette Heyer quoted in her obituaries in the Times and The Sunday Telegraph, July 1974.

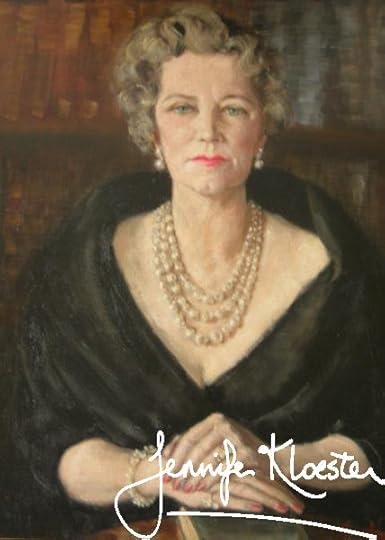

The oil painting done of Georgette Heyer in 1958. Her son, Richard, always said she looked as though ‘someone had trumped her ace’.

The oil painting done of Georgette Heyer in 1958. Her son, Richard, always said she looked as though ‘someone had trumped her ace’.“A household name”

It may seem unusual – especially in this era of celebrity – for such a successful author to be so resolute in eschewing every opportunity for publicity, but this is what Georgette Heyer chose to do. She did not appear in public or do book signings or give talks or open fetes as many authors did at the time, and the only interview she ever gave (to a a journalist from the Australian Woman’s Day magazine) was done so on the proviso that the journalist ask her nothing about her writing life. When asked by the BBC if they could record her voice Georgette gave a typically self-deprecating and pithy answer:

‘Record my voice for posterity indeed! few things are more unlikely than that posterity will have the smallest interest in either me or my works.’

Georgette Heyer, letter to Max Reinhardt, CEO, the Bodley Head.

And yet, despite her refusal to engage in personal publicity, in the decade before her death Georgette Heyer had become a household name. She had also given her name ‘to a recognizable genre of fiction, but no rival managed to achieve the touch which charmed both men and women from all levels of society.’ So said the writer in The Times., while in the Sunday Telegraph, the critic, Duff Hart-Davis, described her as a ’20th century Jane Austen’, explaining that:

‘it was in the field of historical romance that she left almost all competitors standing, and for these her secrets were, first, her cool wit, and second, her immensely detailed research.’

Duff Hart-Davis, The Sunday Telegraph, 7 July 1974, p.8.

Though she would have been the first to decry and strongly deny any comparison between herself and her literary idol, the great Jane Austen, the tributes paid to Georgette Heyer after death universally acknowledged her skill in recreating a vivid sense of the period in which Austen herself had lived and written her six famous novels. The writer in The Times described Heyer as “witty, amusing, charming, generous, delighting in the grand manner, a ‘lady of quality’ to quote the title of her last book” and also observed that, “Popular her novels were, but there was also a firm core of scholarship and expert knowledge of the Regency period, its fashions, politics, military and social history, modes of speech, even agricultural policy…”

Georgette Heyer was the consummate professional, a product of her time and class, a repository of the prejudices of her era, an insightful observer, a clever, witty writer of ironic comedies, a daughter, a sister, a wife, a mother and a friend. She was formidable, intensely shy and very, very private. She enriched the world with her many wonderful novels and there is much, much more to say about her life and her writing. But, for now, on the eve of the anniversary of her passing all those years ago, I am happy to simply think of her as I take up my copy of Sylvester and once again immerse myself in the comfort of re-reading Georgette Heyer.

July 1, 2020

The International Heyer Society – Celebrating Georgette Heyer

It is such a delight to announce the launch today, July 1st 2020, of the International Heyer Society and, in conjunction with my fellow Patronesses, Rachel Hyland and Susannah Fullerton, invite you to join us in sharing the joys of Georgette Heyer. September 2021 marks one hundred years since the publication of Georgette Heyer’s first novel, The Black Moth, written when she was just seventeen. As we look forward to celebrating her centenary in London, New York, Melbourne and Auckland (Covid-19 permitting), we will keep you well informed about the inimitable Georgette with our monthly circular, Nonpareil, in which we discuss her works in detail, along with weekly communications, quarterly digital talks and Q&As with Heyer experts, plus other membership bonuses. It doesn’t cost much to join the International Heyer Society and we look forward to meeting many of her fans as well as lots of new readers online.

The front page of Nonpareil, the official monthly journal of the International Heyer Society.

The front page of Nonpareil, the official monthly journal of the International Heyer Society.“Aunt Georgette would have been delighted”

With members from all over the world already signed up to the Society we are delighted to have a message of support from her nephew, Major-General Jeremy Rougier, who writes:

I know that my Aunt Georgette would be have been quite delighted to know that her books have been widely translated into French, German and Italian editions and that you are now launching an international society to celebrate all things Georgette Heyer. In married life she was Mrs Ronald Rougier and a very formidable personality, married to my father’s younger brother Ronald, who was a QC and an international bridge player. I can well remember the times when in my teenage years my Mother and I were summoned for lunch and then to play bridge with them in their set in The Albany, Piccadilly, an upmarket address second only to Buckingham Palace. It was never a relaxing experience for me. She used to call me “dear boy” which I always suspected was because she couldn’t remember my name. But when I got to know her better in later years I fully realised what a charming, humorous and generous person she was; quite, quite special.

Major-General Jeremy Rougier, 1 July 2020

Georgette Heyer was indeed a very special person – a writer whose novels continue to give hours of reading pleasure to millions around the world. It is so exciting to be part of this new society and to share her brilliant and enduring novels with you. I do hope you will find your membership of the International Heyer Society an enriching and rewarding experience.

A success from the very beginning

A success from the very beginning Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novels

Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novels Georgette Heyer loved writing her many novels

Georgette Heyer loved writing her many novels

June 26, 2020

Pastel – telling too much?

In April 1928 Georgette and Ronald returned home from Tanganyika. After eighteen months in East Africa prospecting for tin, Ronald still had not ‘struck it rich’ and had decided to try his luck elsewhere. After a brief holiday in Uganda, the Rougiers sailed home from Mombasa, stopping along the way at Dar-es-Salaam, Zanzibar and South Africa, before arriving back in England in early April,. The week before they arrived home, Georgette’s second contemporary novel, Helen, had appeared in the bookshops with a long review in the Times Literary Supplement which concluded with the gratifying statement that, ‘this is a story which contains some good work.’ Georgette had by now moved on from Hutchinson’s and it was Longmans who published Helen. They would publish three of Heyer’s modern novels as well as her earliest detective fiction. Returning from Africa, Georgette set to work on a new book, Pastel her second modern novel for Longmans and which would contain much that was familiar to her.

The stunning1929 first edition cover of Pastel with its beautiful art deco design by well-known graphic artist ,Theyre Lee Elliott

The stunning1929 first edition cover of Pastel with its beautiful art deco design by well-known graphic artist ,Theyre Lee ElliottBut not for long…

Once back in England, the Rougiers returned to London where Georgette’s mother was living in rented rooms at 44 Stanhope Gardens in South Kensington. It is not known if they lived with her or whether they found their own place to rent. Wherever they settled, however, it was not for long. Ronald was eager to obtain another overseas posting and that summer he found a job in Macedonia working for the Kratovo Venture Selection Trust Ltd. By August he had left London and made his way to the Macedonian capital, Skopje. From there he travelled by bus or car to their new home in Kratovo, a small village about an hour’s bus ride east of Skopje. As its name indicates, Kratovo lay inside the burnt-out crater of an ancient volcano. It was a small village but the surrounding area had been mined for its precious metals since Roman times. Ronald’s job would take him into the lead mines near the Bulgarian border where Georgette would later report seeing the names of slaves been carved into the rock centuries earlier.

44 Stanhope Gardens, South Kensington, where Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, was living when they returned from East Africa in 1928.

44 Stanhope Gardens, South Kensington, where Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, was living when they returned from East Africa in 1928. The medieval town of Kratovo where Georgette Heyer lived from 1928 to 1930. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kratovo,_North_MacedoniaFrom London to Kratovo was another marked change in Georgette Heyer’s writing life.

The medieval town of Kratovo where Georgette Heyer lived from 1928 to 1930. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kratovo,_North_MacedoniaFrom London to Kratovo was another marked change in Georgette Heyer’s writing life.Two books a year!

Perhaps because she was busy working on Pastel , Georgette did not travel out to Macedonia with Ronald that August but instead joined him there later in the year. She may also have wished to be in England for the release of her second novel, The Masqueraders, which came out in early September. It was a remarkable achievement to have two books out in a single year, but 1928 would mark the beginning of a a prolific period for Georgette Heyer. In the fourteen years between 1928 and 1941, she would write twenty-four novels with a average of two a year for all but three years (1931, 1933, 1939). Her publishers must have loved her! Heyer was unusual in having two different publishers for her work but the arrangement seemed to suit her with Heneimann publishing her historical fiction and, Longmans publishing her contemporary and detective fiction. For over a decade, Georgette alternated between writing historical novels and her modern or detective novels and it is a mark of her extraordinary skill that she was very successful in all three genres.

Published by Longmans in April 1928

Published by Longmans in April 1928 Published by Heinemann in August 1928For fourteen years, from1928 until 1941 Georgette Heyer wrote an average of two books a year.

Published by Heinemann in August 1928For fourteen years, from1928 until 1941 Georgette Heyer wrote an average of two books a year.‘Here is a book for Mummy’

In her previous contemporary novel, Helen, Georgette had created a fictional life-story for her heroine that at times drew on her own life and experiences to the extent that her brother, Frank Heyer, always said that Helen was her ‘most autobiographical book’. In Pastel Heyer would again draw on her experiences, though it is impossible to know just how much. A very telling and somewhat startling aspect of Pastel is revealed in the personal dedication which Georgette wrote in the front of her mother’s presentation copy:

‘Here is a book for Mummy, which is sent with love and the hope that She will like it. Some of it she may disagree with; some of it is designed to make her laugh; but whether she laughs or whether she frowns, this book should, on the whole, please her since it contains so much that is Really and Truly her – Dordette – Kratovo, April 1929’

Georgette also formally dedicated to her mother and it is tantalising, though not always easy, to try to discern Sylvia Heyer within the pages of the book. Pastel is the story of two sisters, Frances and Evelyn Stornaway, who live with their parents in quiet, suburban, middle-class “Meldon” – a thinly disguised version of Wimbledon where Heyer grew up. Frances is the elder of the two and a sensible, reliable young woman who ‘could look almost beautiful’. She is often in the background, however, because Evelyn is so vivid and vibrant and always the centre of attention. The two sisters actually look a lot alike, but Frances is the ‘pastel’ version of her sister – ‘a pale edition of Evelyn’ is how Heyer describes her. At a weekend house party, to which Evelyn is not invited, Frances meets Oliver Fayre and falls in love with him. He is the handsome romantic ‘hero of Asgard’ of her dreams, but when he meets her sister Evelyn it is love at first sight. No one but her mother ever suspects Frances’s passion and at every turn Mrs Stornaway fails to comfort her lovelorn daughter. Though she loves her mother, Frances struggles to find solace in Mrs Stornaway’s prosaic, practical advice that it is often ‘the dull things [that] turn out to be the most satisfactory’ nor is she helped by knowing that her mother hasn’t ‘much faith in the lasting qualities of a grand passion’. Neither statement gives Frances comfort as she struggles to suppress her envy when Evelyn wins Oliver’s heart and hand. Like Sylvia Heyer, Mrs Stornaway is Victorian, conservative, and unable to perceive her daughter’s deeper emotions. She wants Frances to marry Norman Acre, ‘who was such a dear boy and whom they had known for so many years’ and when Frances finally manages to confess something of her feelings for Oliver her mother tells her:

You know, dear, it isn’t always the first man you fall in love with who turns out to be the right one.’

‘And if Oliver wants Evelyn, don’t feel bitter about it. I like him very much, and I know just how his type attracts you. But he isn’t the sort of man I would choose for you, darling. I think you’ll realize that yourself one day.’

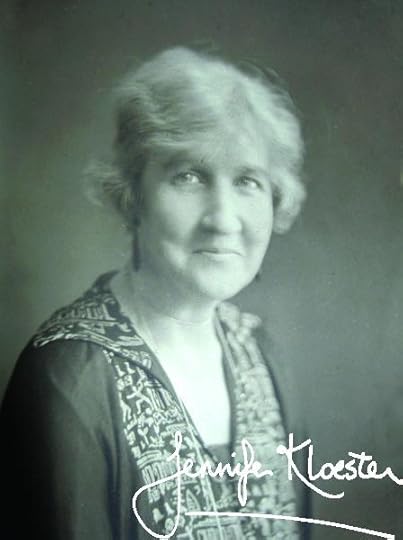

Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, to whom Georgette dedicated

Pastel

. Though Georgette loved her mother, she and Sylvia had a complex and sometimes difficult relationship. (Used with permission)

Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, to whom Georgette dedicated

Pastel

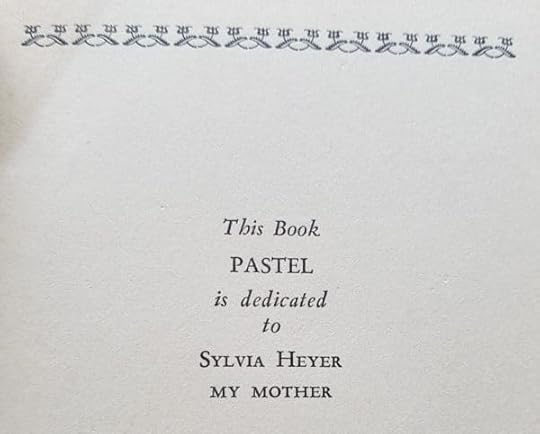

. Though Georgette loved her mother, she and Sylvia had a complex and sometimes difficult relationship. (Used with permission) The formal dedication to her mother but the personal dedication is a far more tantalising inscription to ‘Mummy’.

The formal dedication to her mother but the personal dedication is a far more tantalising inscription to ‘Mummy’.Norman Acre vs. Ronald Rougier

The parallels between fictional Norman Acre and real-life Ronald Rougier are many – both men are strong, good-looking and sensible, they both smoke a pipe, play rugby (rugger) and ride a motor-bike with a side-car in which Norman takes Frances to watch football matches jjust as Ronald took Georgette befor they were married. Both are quiet men, ‘hard to ruffle’ and each is sufficient in himself. In Pastel Georgette describes Norman as:

‘Phlegmatic, stolid: these you might call him; dogged, in the style of your true Rugby football player; dull, that you might call him if you were Frances Stornaway.’

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, 1929, p.3.

It seems unlikely that Georgette found Ronald dull, but the fictional and the real man have other things in common: both have known the woman they want to marry for several years and each is looked on with approval by the ladies’ parents, neither is ‘a hero of Asgard’ like Oliver Fayre and neither invokes in Frances or Georgette the kind of grand passion that Frances, at least, dreams of attaining. It is impossible to know whether Georgette Heyer ever dreamed of a ‘grand passion’, but Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, always believed that there had been someone in Georgette’s life whom she had passionately loved and who for some reason she could not marry. In Pastel Mrs Stornaway assumes that Frances’s feelings for Oliver are something from which she will quickly recover but Frances admits to herself that:

‘it went deeper than that. If it were no more, very pride would have nipped it in the bud. The love she felt had not died when Oliver turned to Evelyn: it consumed her still, and she knew that Oliver was the one man who could give her happiness ideal. If he had cared she would have found herself capable of treading the heights Mrs Stornaway seemed to disparage. He did not care, and Frances felt that the one chance given to each person in life had slipped by her.

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, p.72.

The 1931 Longman Novels cheap edition. In the early 1930s Longmans reprinted all four of Heyer’s contemporary novels in this style.

The 1931 Longman Novels cheap edition. In the early 1930s Longmans reprinted all four of Heyer’s contemporary novels in this style.A better choice

Eventually Evelyn marries Oliver and Frances settles for Norman who, like his name is very ‘normal’, but who in the end – just as Frances’s mother predicted – is a much better choice for her. Reading Pastel it is hard not to think that the novel reflects many aspects of Georgette’s own relationship and marriage.

‘He was not Romance, but he was her husband, and she did care for him. If she was not passionate that was the fault of her temperament. She thought of the man who might have meant Romance, and awaked passion obtruded for an instant. She banished it swiftly. Norman must never know that he was second-best. All thought of Oliver Fayre faded; best or second-best. Norman was her man, and she felt for him something of that protective, maternal love that decreed that nothing should worry or distress him. She got up and went to him. It was not pretence that made her eyes soft and bright with tears; passion might be lacking, but she had love for Norman. He was a dear, and so good to her, and when she saw his face set, and a little anxious, somthing smote her heart, and she wanted to comfort him, and to kiss him too, though not in that desperate, hard way that he seemed to require of her.

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, 1929, p.186.

Telling too much… ?

Pastel is interesting not only for its autobiographical elements and account of middle-class life in 1920s England but also for its intimate portrait of Frances and Norman’s marriage. It is easy to think that the conversations between the newly married pair, as well as the passages of introspection in which Frances tries to work out her feelings about Norman, are a direct reflection of Georgette’s own experience of marriage to Ronald. I think that Pastel is the closest we will ever come to understanding the young, married Georgette. She is not Frances in all her incarnations, but her descriptions of Frances’s feelings – especially in in the last part of the novel – seem to align with what we know of Heyer from her early letters and from her attitude to Ronald as her first reader and counsellor. It may have been because the novel revealed too much of her life and attitudes that in the late 1930s Georgette Heyer firmly suppressed Pastel.

The later 1934 edition published as part of a uniform set of her modern novels with the logo: ‘A Love Story by Georgette Heyer’. She would have hated the cover and the logo.

The later 1934 edition published as part of a uniform set of her modern novels with the logo: ‘A Love Story by Georgette Heyer’. She would have hated the cover and the logo.

June 19, 2020

The Masqueraders – written in a grass hut

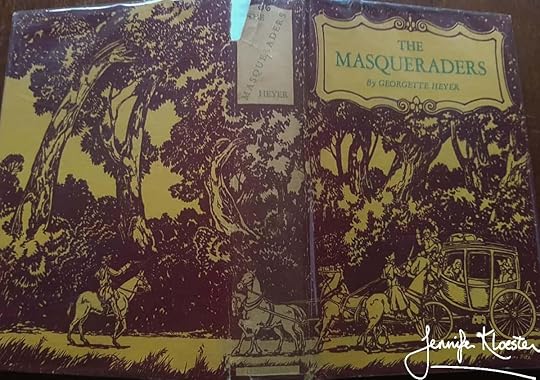

The first edition jacket of Georgette Heyer’s third eighteenth-century novel. She wrote it while living in a grass hut in Africa.

The first edition jacket of Georgette Heyer’s third eighteenth-century novel. She wrote it while living in a grass hut in Africa.‘A sister takes her brother’s sword and the brother uses her fan.’

A joyful return

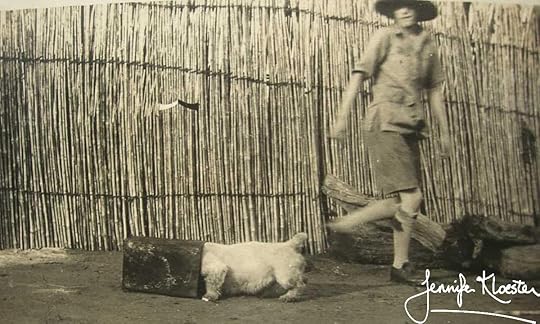

In 1927 Georgette Heyer was living in Kyerwa, a remote part of Tanganyika in East Africa. Her home was a hut made of elephant grass built inside a compound surrounded by a tall elephant grass fence. On the grassy plains outside rhinoceroses, leopards and roan antelope roamed free. Georgette’s husband, Ronald, was prospecting for tin and often away, so she spent her days writing, going for walks and playing with her Sealyham terrier, Roddy. Earlier that year she had finished her contemporary novel, Helen, a book which had helped her overcome the deep grief caused by her father’s unexpected death two years previously. If Helen was a cathartic novel, The Masqueraders was a joyful return to the type of book Georgette Heyer would always love to write.

Georgette and Roddy the dog nside the elephant grass fence surrounding their compound in Kyerwa. (Used with permission)

Georgette and Roddy the dog nside the elephant grass fence surrounding their compound in Kyerwa. (Used with permission) Georgette outside ‘the manor house’, her name for the grass hut that was her home in Africa. (Used with permission)Life in East Africa was unlike anything Georgette had experienced before but the remote location did not stop her writing.

Georgette outside ‘the manor house’, her name for the grass hut that was her home in Africa. (Used with permission)Life in East Africa was unlike anything Georgette had experienced before but the remote location did not stop her writing.Writing in the ‘Manor House’

It is remarkable to think of Heyer writing The Masqueraders in a grass hut in Africa, thousands of miles away from her previous home in staid Wimbledon. She was separated from her reference books and from the London Library, and yet she still managed to pull off a convincing eighteenth-century setting. It’s amazing to think of her working away inside the ‘Manor House’ – her name for her grass hut – writing her manuscript on her lap or at a rudimentary table with a fountain pen. The hut had earthen floors and thin grass walls and it must have been hot both inside and out. Perhaps it’s not surprisng that The Masqueraders is one of her rare books in which it rains. From the very first sentence Georgette sets a scene that could not have been more different from the world in which she was living:

‘It had begun to rain an hour ago, a fine driving mist with the sky grey above. The gentleman riding beside the chaise surveyed the clouds placidly. “Faith, it’s a wonderful climate,” he remarked of no one in particular.’

The Masqueraders, Pan, 1965, p.7.

An utterly convincing, improbable tale…

For many Heyer readers, The Masqueraders remains a firm favourite. In the novel Heyer once again makes use of cross-dressing, with her tall heroine masquerading as a man and her shorter, slender brother disguised as a beautiful young woman. Five years earlier Georgette had told her agent that having her character masquerade as a boy was something that ‘always attracts people’; in The Masqueraders she took the plot device to a whole new level. It is perhaps a reflection of Heyer’s skill that she makes this rollicking confection of a tale so convincing. As award-winning author Kathleen Baldwin explains in her essay in Heyer Society :

Here she adroitly weaves an improbabe tale of cross-dressing siblings who escape the noose, vanquish evil and bamboozle high society, all while the clever duo falls charmingly and humorously in love with equally interesting counterparts. In The Masqueraders, Georgette Heyer convinces us of the impossible. She does so with such finess and confidence…

Kathleen Baldwin, ‘Splash, Dash and Finesse! Heyer’s Magical Pen and Indomitable Spirit on Display in The Masqueraders, Heyer Society, p.87.

Homeward bound

Early in 1928 Georgette and Ronald left Africa and returned home to England. Before leaving Tanganyika they enjoyed a holiday, travelling north from Bukoba on the western shore of Lake Victoria (Nyanza) to Kampala in Uganda, stopping at Bukatata and Ripon Falls along the way. From Kampala they travelled to Mombasa on the south-east coast of Kenya where they boarded the ship, S.S. Usarama. Their voyage home took them via Zanzibar, where they visited the Sultan’s Palace, and Dar-es- Salaam where they picked up some interesting curios, including a knife which Ronald bought ‘by low barter’ at the market. From there they sailed to South Africa, stopping in the province of Natal and visiting the Valley of the Thousand Hills before embarking ship again. After stops at Port Elizabeth and Capetown, their ship sailed up the west coast of Africa, calling in at Walvis Bay and Lüderitzbucht (as it was known then), before sailing on to England and home.

Ronald and Roddy the Sealyham terrier on the voyage home from Africa. (Used with permission)

Ronald and Roddy the Sealyham terrier on the voyage home from Africa. (Used with permission) Georgette dedicated The Masqueraders to her husband, George Ronald Rougier.

Georgette dedicated The Masqueraders to her husband, George Ronald Rougier.Home again

Georgette and Ronald arrived home on 27 April 1928. Georgette’s novel Helen had come out the week before – her first novel to be published by Longmans who would also bring out the book in America. Home again, she delivered the manuscript of The Masqueraders to Heinemann who were to publish it in September with a colourful, eye-catching cover. The Rougiers settled back into life in London and with two books in hand, Georgette had time to be leisurely. In June she and Ronald embarked on an ‘England Tour’, visiting various historical sites including Tintern Abbey in Wales. Georgette greatly enjoyed visiting historical sites and would make several such trips in the future. For now, however, Ronald was keen to set off on another mining adventure and in August he left England for the lead mines in Kratovo in Northern Macedonia. Georgette would follow soon afterwards but not before finishing her third contemporary novel.

Published in America

The Masqueraders came out on 30 August and Georgette sent an advance copy to Ronald in Kratovo. Some days later she received a telegram from her admiring husband which read: ‘Congratitations. Find Mahineroders excellent’. In December Georgette travelled out to Kratovo and settled into her new life in the Macedonian countryside. The following year she had the satisfaction of seeing The Masqueraders published in America. The US edition had a stunning cover that must have pleased her for it not only reflected the style and tone of her novel but also depicted a scene from the book. The Masqueraders did well wherever it was published but Georgette was far from home again and busy writing her next historical novel.

Published by Longmans in July 1929, the first US edition’s dustjacket reflected the style and tone of the novel.

Published by Longmans in July 1929, the first US edition’s dustjacket reflected the style and tone of the novel.June 12, 2020

Helen – a very revealing story

Georgette Heyer’s second contemporary novel, Helen, would also be her most autobiographical. She had struggled to write after her father’s sudden death in June 1925 and given up any thought of writing a ‘period’ novel. Though she loved writing historical fiction – especially the high-spirited, vivid novels with which she was making her name – Georgette needed to be in a positive frame of mind to do so. This eluded her for many months after her father’s death. When she did at last return to her writing, it was to pen the book that would be her most cathartic and her most revealing; years later she would firmly suppress it.

Helen was Georgette Heyer’s first novel written after her father’s sudden death and her first book to be published by Longmans.

Helen was Georgette Heyer’s first novel written after her father’s sudden death and her first book to be published by Longmans. This is the first edition dustjacket.

An outlet for grief

Helen tells the story of Helen Marchant, from her birth and the immediate death of her mother, through her childhood and adolescence into the tumultuous years of young adulthood. Helen’s father decides to raise his only child himself and he and Helen become inseparable. She adores him – much as Heyer adored her own dad – and Marchant raises his Helen in his own particular way, just as Georgette’s father did:

‘Himself had taught Helen to read and write, while in long talks with her he had instilled into her a not inconsiderable knowledge of history and literature’

‘I don’t want Helen educated for a profession and made to pass Matriculation. I want her mind to expand. I want her to be accomplished in the sense that she has a wide knowledge of art and history, and literature, and the things that matter.’

Helen, Georgette Heyer, Longmans,1928, pp. 44 & 46.

There are many moments in Helen that echo moments in Georgette Heyer’s life, but the most telling part of the book comes at the end when Marchant dies suddenly and Helen is left utterly bereft. Throughout the book, Helen is depicted as someone who doesn’t show her feelings – who cannot bear ‘to have them touched’. This was Georgette’s way, too: ‘There was reserve in that voice, and an instinctive recoil from any impending intimacy.’ Writing Helen gave Georgette an outlet for her deepest feelings and it was an outlet that only she and those who knew her best would ever know about.

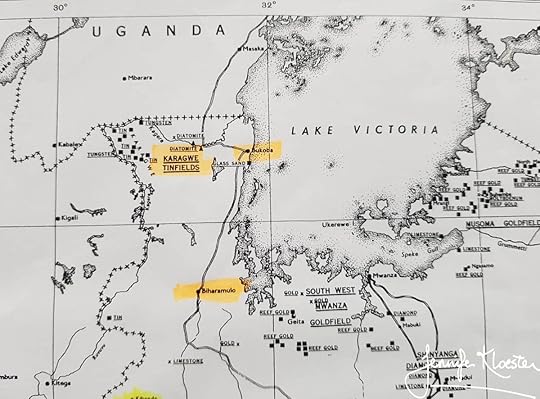

A grass hut in Africa

It is not known exactly when Georgette began writing Helen. She may have begun it before leaving for Africa in December 1926 or she may have written the whole novel in the grass hut that was to be her home for the next eighteen months. In the autumn of 1926 Ronald had gone out to Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania) in East Africa to prospect for tin with the hope of striking it rich and Georgette had joined there him a few months later. Their new home was genuinely remote for Ronald was prospecting in the Karagwe tin fields about eighty miles as the crow flies from the western shores of Lake Victoria. It was an extraordinary change from life in staid Wimbledon, but Georgette seems to have enjoyed the experience. In those early years of their marriage she had a definite taste for adventure and she adapted to life in Africa remarkably well.

Georgette and Ronald crossed Lake Victoria by boat to Bukoba and then journeyed about 150 miles by lorry to Karagwe.

Georgette and Ronald crossed Lake Victoria by boat to Bukoba and then journeyed about 150 miles by lorry to Karagwe. Georgette appeared to be at her most relaxed in remote East Africa. (used with permission)

Georgette appeared to be at her most relaxed in remote East Africa. (used with permission) Ronald hoped to ‘strike it rich’ prospecting for tin in Karagwe. (used with permission)

Ronald hoped to ‘strike it rich’ prospecting for tin in Karagwe. (used with permission)Georgette finished Helen in the two-room hut made of elephant grass which was her home in East Africa. She and Ronald lived in a simple compound along with a number of other British prospectors; Georgette was the only white woman for 150 miles. With characteristic humour she named their hut ‘the Manor House’ and it was there that she wrote on her lap by the light of an oil lamp. Despite the exotic location and the presence of wild animals including rhinos and antelope, apart from one article for the Sphere magazine, Georgette did not write about her African experience. Instead she was content to continue writing about contemporary life in England and eventually to pen a historical romance.

Memories of the Great War

Helen was not only an outlet for Georgette’s grief over her father’s death, it was also a way for her to write about some of her memories of the Great War. Like the fictional father in Helen, Georgette’s father had also enlisted as an over-age soldier, while Helen becomes a VAD nurse. While Georgette was too young to serve in any official capacity during the War, her mother and her two favourite aunts, Cissie and Jo, each joined the Royal Red Cross and worked as Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses (VADs) during the First World War. Aunt Cissie and Aunt Jo also became senior officers in the Royal Red Cross. Though they probably shielded the adolescent Georgette from the harsher details of their nursing experience, she was bright and observant and her understanding shows through in Helen, in which several of her characters work as VAD nurses. The novel also deals with the departure of all of Helen’s male friends for the Front and the deaths of a number of them. In a way, Helen is also a kind of tribute to the men she knew who did not return from the War.

Georgette’s Aunts Cissie & Jo (at left) in their outdoor uniforms outside the gates of Buckingham Palace after an awards ceremony. (used with permission)

Georgette’s Aunts Cissie & Jo (at left) in their outdoor uniforms outside the gates of Buckingham Palace after an awards ceremony. (used with permission) Georgette’s father, Captain George Heyer, who enlisted as an over-age soldier in 1915 and served behind the lines in France. (used with permission)Georgette was 12 when War broke out, so too young to serve. However, both her parents and other family members ‘did their bit’ for the War effort.

Georgette’s father, Captain George Heyer, who enlisted as an over-age soldier in 1915 and served behind the lines in France. (used with permission)Georgette was 12 when War broke out, so too young to serve. However, both her parents and other family members ‘did their bit’ for the War effort.A piece in Punch

During my research into Georgette Heyer’s life and writing, I was delighted to find this piece in Punch magazine. The poet is unknown, but whoever he or she was, they had undoubtedly read and enjoyed Helen. Though the poem is not without its gentle criticism of Georgette’s most autobiographical novel, it ends with kind encouragement for the young author. Georgette’s father had had several of his humorous poems published in Punch and it must have been satisfying to have her latest novel recognised in the pages of such a famous magazine. One cannot help wondering, however, what Georgette thought of this poem about Helen.

A poetic review of Georgette Heyer’s most autobiographical novel,

Helen

, author unknown.

Punch

13 June 1928.

A poetic review of Georgette Heyer’s most autobiographical novel,

Helen

, author unknown.

Punch

13 June 1928.A Popular novel

Although Heinemann would still publish Georgette’s historical fiction, her agent had found her a new publisher for her contemporary novels. Longmans were enthusiastic and pleased to publish Helen in April 1928. Helen proved popular and by October 1936, the novel had been reprinted eleven times. In their first reprint of Helen, Longmans used the original black and yellow cover art with its picture of the young woman draped around a large potted plant: An unusual image and unlikey to have pleased Georgette. The cover for the first 3/6- edition with its bold black and orange graphics may have been more satisfactory, but she would have loathed the jacket for the 1936 ‘love story’ edition. Longmans would go on to reprint each of Heyer’s four contemporary novels with similar melodramatic, coloured wrappers, with the words ‘a love story by Georgette Heyer’ on the spine. These jackets may have been the impetus for Georgette to suppress her four contemporary books in the late 1930s.

The 1931 cheap edition. Longmans used this style of jacket for each of Heyer’s four contemporary novels.

The 1931 cheap edition. Longmans used this style of jacket for each of Heyer’s four contemporary novels. Georgette would have loathed the melodramatic cover of the 1936 edition.

Georgette would have loathed the melodramatic cover of the 1936 edition. Three of Georgette Heyer’s four contemporary novels. In the later 1930s, her publisher, Longmans, published them with the words: “A love story by Georgette Heyer” on the spine, something she would have found both distasteful and inaccurate.

Three of Georgette Heyer’s four contemporary novels. In the later 1930s, her publisher, Longmans, published them with the words: “A love story by Georgette Heyer” on the spine, something she would have found both distasteful and inaccurate.Worth reading

Georgette Heyer’s four contemporary novels are well-written, interesting books, reflective of their time. Their greatest value lies in what they tell us about the author as well as the picture they draw of middle-class life in post-WWI England.. Of the four books, Helen is the most revealing about Heyer’s life and struggles with personal tragedy. She never fully recovered from her father’s death and in time her writing would become her greatest solace and the outlet for her deepest emotions.

June 8, 2020

These Old Shades – always a favourite (Part 2)

These Old Shades

These Old Shades

Changes

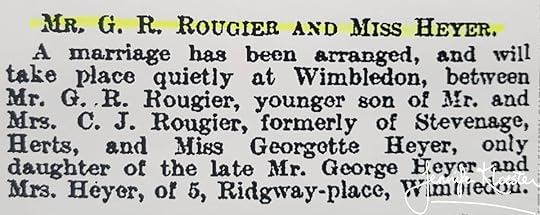

On 15 June 1925 George Heyer had a heart attack and died in front of his 22-year-old daughter. Georgette never fully recovered from the loss and her father’s death changed everything for her family. Her mother, Sylvia, had lost her husband and the family breadwinner and for the rest of her life she would live in hotels and rented rooms, never fully adjusting to the life of a genteel, middle-class widow. Georgette’s brothers were only 13 and 17 when their father died and it soon became clear that their older sister would need to help the family financially – no easy task. Caring deeply for Georgette and only recently returned from Africa, her old beau, Ronald Rougier asked her to marry him. On 20 July 1925, only one month after her father’s death, an announcement appeared in the TImes.

The announcement of Georgette and Ronald’s engagement, The Times, 20 July 1925.

The announcement of Georgette and Ronald’s engagement, The Times, 20 July 1925. A wedding

On 16 August, Georgette turned 23. Two days later on 18 August 1925 she married George Ronald Rougier at St Mary’s Church, Wimbledon. It was just two months after her father’s death and so the wedding was just a small, simple one. Georgette had still not been able to return to her writing and must have doubted her ability to do so, for instead of writing “author” she put a line through the box on her marriage certificate marked “Rank or Profession”. It would take more than a year for Georgette to begin writing an entirely new book but completing These Old Shades would help her find her way back to the literary world she loved.

From the Times, 20 August 1925.

From the Times, 20 August 1925. Georgette married Ronald at St Mary’s Church, Wimbledon on 18 August 1925 (used with permission)

Georgette married Ronald at St Mary’s Church, Wimbledon on 18 August 1925 (used with permission) Georgette Heyer’s marriage certificate with the line through the box marked ‘Rank or Profession’ It would be some time before she wrote again.

Georgette Heyer’s marriage certificate with the line through the box marked ‘Rank or Profession’ It would be some time before she wrote again.These Old Shades

Georgette eventually returned to the manuscript she had begun in 1922 and for which she had so enthusiastically made plans in her 1923 letter to her agent. In the first half of 1926, several months after her father’s death, she finished the book and sent the manuscript to her publisher. On 21 October 1921, Heinemann publishedThese Old Shades. Georgette inscribed her advance copy to her new husband with an affectionate message and a hint of her old humour. The exuberance with which she had written the bulk of the book four years earlier would never fully return. Her father’s tragic passing had been a cataclysm in her life and it marked a distinct change in his daughter. It was from this time that Georgette Heyer began eschewing publicity. This was the beginning of her lifelong refusal to market herself or her books through interviews, book signings or public appearances. Though her fans would later regret her stance, it did not affect sales ofThese Old Shades in the slightest.

My dear,

Once you were given a novel by a friend who bore the name written upon the title page: she gives you now her new novel, but she bears another name today, and presents this book not in memory of past feuds; but with her love. G.R.

Dedication from Georgette Heyer to her husband Ronald Rougier on the flyleaf of her first edition copy of These Old Shades.

Bestseller!

An instant success, These Old Shades would go on to become a huge bestseller. In its first ten years it would be reprinted nearly thirty times. Readers everywhere loved the tale of the sinister Duke of Avon, nicknamed ‘Satanas’ and his encounter with the red-haired runaway, Leon. Having bought the ‘boy’ and made him his page, the Duke embarks on a journey of revenge, love and redemption. Leon becomes Leonie and with a brilliant supporting cast, including the duke’s irrepressible brother, Rupert, his spoilt sister, Lady Fanny, and the dastardly Comte de Saint Vire, Georgette carries the story to its dramatic climax. These Old Shades sparkles. It has an energy that, even today, still draws the reader into its vivid and vivacious world of colour and movement, adventure and pathos. A favourite re-read for many Heyer fans, this 94-year-old novel has endured beyond the wildest imaginings of its youthful author.

Georgette Heyer’s 1926 bestselling novel

These Old Shades

has had many reprintings.

Georgette Heyer’s 1926 bestselling novel

These Old Shades

has had many reprintings.A very special edition

In 1937 Heinemann published a special leatherbound edition of Georgette Heyer’s bestselling book These Old Shades. She was one of fifteen eminent authors selected for the series, her novel standing alongside books by Joseph Conrad, Somerset Maugham, D.H. Lawrence, Will Cather and J.B. Priestley, among others. The new edition showed how much her publishers thought of her work and reflected her standing as a highly-regarded author. By 1937 Georgette had written 23 novels and established for herself a large, diverse and growing audience. Men and women devoured her books and her publishers eagerly awaited their ‘annual Georgette Heyer’ novel. These Old Shades would be just one of her brilliant achievements.

The special leatherbound edition published by Heinemann in 1937

The special leatherbound edition published by Heinemann in 1937 Georgette Heyer was one of fifteen eminent authors chosen for the special edition

Georgette Heyer was one of fifteen eminent authors chosen for the special editionA nod to Austin Dobson

The title to one of Georgette Heyer’s most popular novels has puzzled some readers. These Old Shades is a phrase taken from one of Austin Dobson’s poems entitled ‘Epilogue’. It was published in his Eighteenth Century VIgnettes and the poem is a humorous comment on Dobson’s own fascination for eighteenth-century life. Dobson was one of the poets who, in the late 1800s, helped to revive many of the medieval poetic forms such as the villanelle, the rondeau and the ballade – poetic styles which Georgette’s father loved and which she would use in her novel, The Transformation of Philip Jettan. Austin Dobson’s entry in Britannica explains that it was his ‘polish, wit, and restrained pathos that made his verses popular’.

.The poet Austin Dobson was a favourite of Georgette’s father’s

.The poet Austin Dobson was a favourite of Georgette’s father’s Georgette drew her novel’s title from Asutin Dobson’s poemThe poem ‘Epilogue’ taken from Austin Dobson’s Eighteenth Century Vignettes

Georgette drew her novel’s title from Asutin Dobson’s poemThe poem ‘Epilogue’ taken from Austin Dobson’s Eighteenth Century Vignettes