Jennifer Kloester's Blog, page 5

March 19, 2021

The Foundling – Inspired by Austen

The very accurate first edition jacket blurb of Georgette Heyer’s 1948 novel, The Foundling.Georgette and the “Great Jane”

The very accurate first edition jacket blurb of Georgette Heyer’s 1948 novel, The Foundling.Georgette and the “Great Jane”Jane Austen was Georgette Heyer’s favourite author and Austen’s six novels her choice of literature should she ever have been marooned on a desert island. A close reading of Heyer’s own novels reveals many moments where she pays homage to the “Great Jane” through her use of Austenesque humour, witty dialogue, town and country settings and characters whose personality and behaviour frequently show them to be literary descendants of some of Austen’s greatest creations. Not that Heyer copies Austen – her regard for the creator of Emma and Pride and Prejudice was too great for that – but she does draw inspiration from her literary idol and there are many instances where Heyer borrows from Austen an encounter, a minor theme, a character, a setting, a phrase or piece of dialogue as a starting point for a scene in her novels. In 1947, when Georgette began writing a new Regency novel to be called The Foundling, one suspects she had been reading Jane Austen again and very likely Emma.

The 1948 plain wartime jacket for The FoundlingA young and foolish foundling

The 1948 plain wartime jacket for The FoundlingA young and foolish foundlingIt is in Emma that the eponymous heroine befriends the young and foolish foundling, Harriet Smith, and sets about directing her life. Harriet Smith is pretty and naive and in love with the prosperous young farmer, Robert Martin, who has offered her marriage. However, Emma disapproves of the match and encourages Harriet to refuse Martin. Instead, Emma engages to find Harriet a “more suitable” husband in the new clergyman, Mr Elton. Emma is the story of a bored young woman shackled by gentle domestic tyranny who seeks to alleviate her boredom by match-making and managing other people’s lives. The Foundling is the story of a bored young man shackled by gentle domestic tyranny who seeks to alleviate his boredom by escaping from other people’s match-making and their well-meant management of his life. In both novels the foundling is the device each author uses to teach her main character some much-needed life lessons.

Of course, as she would have been the first to admit, Georgette Heyer is not Jane Austen. Rather than imitate her favourite author, Georgette repeatedly pays homage to Austen by frequently taking an Austen element as a starting point and then taking her story in a completely different direction. The Foundling is a sparkling example of Heyer’s determination never to attempt to imitate the author she admired above all others. A few examples: where Emma’s journey of self-discovery takes place entirely within the confines of her village, Gilly’s journey requires him to leave his cloistered home and go out into the world; in Emma the charming scoundrel, Frank Churchill, is hidden in plain sight, whereas in The Foundling, the charming scoundrel, Liversedge, is instantly obvious; neither Emma nor Gilly perceive their ideal partner at first – though both Mr Knightley and Harriet are right in front of them. While each eventually discovers their true feelings, Emma’s epiphany comes from an external threat in the form of Harriet’s purported love for Mr Knightley, while Gilly’s comes from within and is the result of having finally learned who he is and what he wants his life to be like. There are many other Austenesque moments in The Foundling, not least in the style of the novel. As the reviewer from the TLS remarked:

“A really flowering success”‘There are frequent echoes of Jane Austen, for instance, in such a sentence as: “She will always be silly, but he appears to have considerable constancy, and we must hope that he will always be fond.”

“Period Pieces”, The Times Literary Supplement, 24 April 1948, p.229.

An excerpt from Arnold Gyde’s letter to Georgette Heyer about the blurb he had written for The Foundling

An excerpt from Arnold Gyde’s letter to Georgette Heyer about the blurb he had written for The Foundling On 1 April 1948, the head of the Editorial Department at Heinemann, Arnold Gyde, wrote to Georgette to wish her luck for the publication of The Foundling on April 12th. In a kind and empathetic letter, Gyde also told her that they had sent out ‘the largest list of review copies’ for her books and that Ralph Strauss of The Sunday Times had grabbed his copy of The Foundling with ‘avidity’. Gyde told her how much he had enjoyed the novel and how he felt that Georgettte had ‘developed a sense of comedy’ into a ‘really flowering success’. It was an astute observation forThe Foundling is replete with comic moments.

‘Miss Heyer’s talent is elegant farce and she knows her craft well. It is, without apologies, a lighter-than-air craft.’

Richard Match, “Metamorphosis of the Duke of Sale”, The New York Times Book Review, 21 March 1948, p.20.

Georgette was pleased with the novel and delighted to learn that Woman’s Journal had offered £1000 for the serial rights. This was good money and although she was no fan of the editor, the autocratic Dorothy Sutherland, Georgette knew it could only help her sales to be published in the prestigious magazine. Her antipathy towards Miss Sutherland – brought about by the editor’s repeated alteration of her book titles – for example, Regency Buck to Gay Adventure – is reflected in her comments to her young Australian fan, Rosemary White. Georgette wrote to Rosemary and receiving another food parcel from Australia. Appreciative of the gesture (though not needing the food, for despite rationing, Georgette could still shop for food at Fortnum & Mason’s on the other side of Piccadilly), Georgette wrote to ask Rosemary:

And what, pray, can I possibly send you in return, from this impoverished island? I know you would like a new book by Me, but I can’t send you that, because it won’t appear until March. It is coming out in serial form in Woman’s Journal – one of those horrid monthly magazines which request you to “turn to page 175” after the first few paragraphs. For reasons which I don’t pretend to fathom, the editor has altered my title, which is “The Foundling”, to “His Grace, the Duke of Sale.” Apart from the really awful snob-value of this, I believe the dictum laid down by my son at the age of twelve is correct: A Five-Word Title Won’t Do!

Georgette Heyer to Rosemary White, letter, 27 October 1947.

1948 edition of Woman’s Journal. The magazine regularly featured Georgette’s novels.

1948 edition of Woman’s Journal. The magazine regularly featured Georgette’s novels.It is interesting to note that Georgette, so often deemed a dreadful snob herself, should have marked the snobbery inherent in the revised title of her novel. She was not always a snob, as evidenced by her long friendship with Isabella Banton, her former landlady in Hove, but like most people, she had inherent biases and an unfortunate habit of labelling people en masse, such as the French, the Irish, Jews or Americans, whereas in a one-on-one situation her attitude was often very different. Being intensely shy, Georgette was slow to make friends, but if a person was intelligent (not necessarily educated) and could hold a conversation, over time, she would warm to them and a solid friendship might form, regardless of their background. She did not have a large circle of friends but those she did have, loved and admired her in spite of her biases and forthright (sometimes offensive) opinions. Those opinions often changed over time as she learned and grew and this evolution is also reflected in her novels.

The Book Club edition published in 1948 with an charming depiction of the hero.The Duke of Sale – “I rather love him myself”

The Book Club edition published in 1948 with an charming depiction of the hero.The Duke of Sale – “I rather love him myself”Although Georgette Heyer is famous for describing her heroes as either “Mark I: the brusque, savage sort with a foul temper and a Know-All” or “Mark II: enigmatic or supercilious and suave, well-dressed, rich, and a famous whip,” she did, in fact, devise a number of different kinds of heroes that were neither Mark I nor Mark II. One of these is The Foundling‘s hero, the young and untried, “Most Noble Adolphus Gillespie Vernon Ware, seventh Duke of Sale” – also known to his friends and intimates as “Gilly”. Heyer enjoyed writing this new kind of hero and told Rosemary White that she hoped she would like him:

He isn’t tall, or handsome, or dominant, but I rather love him myself.’

Georgette Heyer to Rosemary White, letter, 27 October 1947.

There is a lot to like about Gilly as he tries to sort out the tangled affairs of a lively and memorable cast of characters. It says much for Heyer’s skill that she was able to so seamlessly weave into the story such a diverse and mismatched set of people. Among these are the foolish but beautiful Belinda (the foundling); young Tom Mamble, the wealthy ironmonger’s son; Lady Harriet Presteigne, Gilly’s shy and gentle betrothed; his big cousin Gideon (whom every reader wishes had his own novel); the autocratic Lord Lionel Ware; the feckless and impulsive Lord Gaywood, Harriet’s brother; and, perhaps most impressive of all, the villainous Swithin Liversedge who, despite his willingness to murder the young Duke, proves astonishingly endearing! Amongst this robust cast of characters the Duke must hold his own. He proves to be a kind, caring and gentle hero (neither Mark I or Mark II) whose innate good manners carry him through many difficult and often hilarious situations.

The first Australian edition of The Foundling published by the Heinemann office in Melbourne in 1948.Harriet and Belinda

The first Australian edition of The Foundling published by the Heinemann office in Melbourne in 1948.Harriet and Belinda‘Unless I do something about Harriet, this will be a novel without a heroine, for no one could call the ravishing Belinda a heroine. And whether I shall let it stand as it is – a leisurely, long book – or whether I shall ruthlessly cut & re-write I know not.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 1 May 1947.

In Heyer’s new novel, the pretty, naive foundling is Belinda. She is wonderfully foolish and disastrously innocent. Always ready to go off with any gentleman who will promise her a purple silk gown, she causes Gilly endless problems. Like Austen’s Emma, Heyer’s foundling is in love with a farmer but, after leaving his home, has no idea how to find him again. As her protector, Gilly, (unlike Emma), has no wish to keep Belinda from marrying her farmer. Instead, he does all in his power to reunite her with Jasper Mudgley. The scene in the novel where Belinda is reunited with her lost suitor, “his sleeves rolled up, and his shirt open to reveal the tanned, sturdy column of his throat” is truly memorable and Heyer perfectly describes its effect on Lady Harriet:

” not even Harriet, with twenty years of strict training behind her, could wonder that Belinda no sooner saw him than she gave a little scream of joy, and, without waiting for the steps of the chaise to be let down tumbled headlong into his arms.”

Georgette Heyer, The Foundling, Pan edition, 1967, p.330.

Harriet is one of Heyer’s unexpected heroines. Depsite being absent for most of the middle part of the book she is crucial to the plot. It is in his relationship with Harriet that the reader clearly sees how much both she and the Duke have changed. Both shy and uncertain at the beginning when Gilly must ask Harriet to marry him, in the final chapters he is a different being. Harriet, too, has evolved and some of their final scenes together are among Heyer’s most poignant and touching.

The 1967 Pan edition of The Foundling.Sir Timothy and Gideon

The 1967 Pan edition of The Foundling.Sir Timothy and GideonAmong Georgette Heyer’s many talents was her remarkable ability to create a fully-formed character in a few lines, a paragraph or half a page. The Foundling has several of these including Lord Lione’s “old crony”, the cynical Timothy Wainfleet. He appears en scene for just on two pages but we know him intimately almost at once:

"I wonder why I did not tell my man to deny me?' mused Sir TImothy. "I never listen to gossip, you know. Really, I do not think I can assist you!" "You listen to nothing else!" retorted Lord Lionel. Sir Timothy looked at him in melancholy wonder. "I suppose I must have liked you once," he said plaintively. "I like very few people nowadays; in fact, the number of persons whom I coridally dislike increases almost hourly."Georgette Heyer, The Foundling, Pan edition, 1967, p.184.One of Heyer’s most popular creations is a man many readers devoutly wish had had his own book. Gideon Ware is the Duke of Sale’s “big cousin”. Gilly’s senior by four years Gideon is a captain in the King’s Life Guards and the only one among the young Duke’s many relatives who does not try to cosset or control him. Gideon is an enigmatic character – one of Heyer’s perceptive men with a lazy smile and way of talking. Very little perturbs him until he comes face-to-face with the rascal, Liversedge, who has kidnapped his cousin. Gideon is all strength of mind and body and stands in useful contrast ot his much smaller, less confident ducal cousin. They are great friends, however, and it is a measure of how much Gilly has learned and grown in confidence as a result of his adventures that, by the end of the novel, he is able to demand, “Gideon, will you have the goodness to allow me to manage my own affairs?”

Heyer had a deep appreciation of Austen’s wit and wisdom and she more than once acknowledged her indebtedness to both Austen’s novels and her letters as sources of language and information about the period. But Heyer drew much more than this from Austen. Although the two writers occupy different spheres in the literary canon, for any reader familiar with both there is much enjoyment to be derived from the clearly Austenesque aspects of The Foundling and many of Georgette Heyer’s other Regency novels.

March 13, 2021

Albany – Georgette’s ideal home

‘Founded in the heart of London in 1803 as a speculative venture, offering apartments to well-to-do bachelors, Albany has, for nigh on two centuries, played host to a rich diversity of inhabitants, embracing both the well-known and the obscure. During this period almost 2,000 people, encompassing some of this country’s most gifted poets, philosophers, playwrights, publishers, novelists, actors, actresses, soliders, sailors, entrepreneurs, industrialists, politicians – including six one-time Prime Ministers – civil servants, peers, Companions of Honour, holders of the Order of Merit, knights, dames, adventurers, eccentrics, pioneers and inventors have made the building their home: two of its residents have even been offered European crowns. Not surprisingly, it has also been an inspiration to some of our ablest writers, featuring in over seventy works of fiction.

Jonathan Ray, Albany: The Prosopography and the Chronology, PhD Thesis, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, 1997.

Albany as it is today. Famous for its privacy and for its location on Piccadilly in the heart of London, Albany exactly suited Georgette Heyer. Moving to the capital

Albany as it is today. Famous for its privacy and for its location on Piccadilly in the heart of London, Albany exactly suited Georgette Heyer. Moving to the capitalIn 1942 Georgette Heyer and her husband, Ronald Rougier, were living in Hove near Brighton. Ronald had completed his training for the Bar and was now working as a barrister in chambers in the Inner Temple in London. The Second World War was in its third year and the Blitz had ended in September 1941. With London less of a bombing target (for now), the Rougiers had begun to think about moving to the capital. The move would mean Ronald could give up the daily train commute and be closer to his work, while Georgette would have easier access to the London Library for her research. Georgett’es friend and publisher at Heinemann, A.S.Frere, lived in Albany with his wife, Pat Wallace (daughter of the famous author, Edgar Wallace) and they encouraged Georgette to think about renting an apartment (known as a “set”) in the famous building. The idea had appeal and on 1 September 1942, she and Ronald visited Albany to look at a possible set to rent. A few days later she reported that:

“I rather fell for it. If we could get a large set we might consider it, as it isn’t expensive, & it’s wonderfully cloistral. Frere has Macaulay’s chambers – very nice, but not quite large enough for us.'”

Georgette Heyer to Leonard Moore

A set in Albany with its drawing room and dining room visible. Residents could choose how to configure their rooms.Known as “Albany”

A set in Albany with its drawing room and dining room visible. Residents could choose how to configure their rooms.Known as “Albany”Originally built in 1771 for the 1st Lord Melbourne as Melbourne House, in 1791 the Melbournes sold the mansion that became Albany to the Duke of York and Albany for £23,570. The Duke also assigned to Lord Melbourne the lease on Dover House in Whitehall. A decade later, mounting debts forced the Duke to sell the mansion and by 1803 it had been adapted into apartments to be known as “Albany”. The developer, Alexander Copland, converted the original mansion house into thirteen sets and built another 54 apartments in two long parallel buildings facing each other in what had been the Italian garden. Designed for “men of rank and wealth”, the Trustees established a set of rules which stipulated that “in order to exclude improper Inhabitants” the apartments could not be let or sold without the Trustees’ consent. Nor could any “Profession, Trade or Business” be conducted without the Trustees’ majority approval. Two hundred years later these same conditions still apply, for the the aim of the Trustees has been to maintain Albany’s longstanding tradition ‘as a discreet bastion of the Establishment and as a refuge for the unconventional. From its inception in 1803 as bachelor quarters, Albany had been a much sought-after address. It is a unique haven in the heart of London and, as one long-established resident put it, ‘People come to live in Albany to disappear.’ It would exactly suit Georgette Heyer.

Albany’s elegant entrance hall.A tranquil oasis

Albany’s elegant entrance hall.A tranquil oasisSince its inception Albany has been home to London’s literati, theatre people, politicians, peers of the realm and those wanting a secluded but beautiful place to live in the heart of the city. Located on Piccadilly and set well back from the road with a cobblestone courtyard and a porters’ office at the front of the building, residents were assured of complete privacy. Contrary to popular myth, there has never been any rule against women living in Albany and they have done so since the 1880s. Once past the porters’ lodge, residents and approved visitors passed through an elegant entrance hall before entering the famous Rope Walk between the two “ranges of apartments” facing each other across this covered walkway. The sets in these two buildings branch off from a series of staircases lettered B to F on the west side and G to L on the east. The set in which Georgette and Ronald would eventually reside was on the F staircase and up a flight of 70 steep concrete steps. Albany was (and still is) a tranquil oasis in the heart of London which had the added benefit of being across the road from Georgette’s favourite grocers, Fortnum & Mason, and her favourite bookshop, Hatchard’s. It is no wonder that Georgette fell in love with Albany.

The famous Rope Walk which gives access to the 54 apartments in the two buildings behind the mansion house. “the most superb sitting-room”

The famous Rope Walk which gives access to the 54 apartments in the two buildings behind the mansion house. “the most superb sitting-room”Georgette was excited by the prospect of Albany and all that it offered. The first set that she and Ronald saw was A.11 which she described as having “the most superb sitting-room, panelled in old pine, with a huge bow window'”. She told her agent that it was a set we “definitely want”, but “whether we get it or not is another matter”. She longed to move in but there were several things to work out first. Acquiring chambers in Albany could be a complicated business and Georgette’s vision for A.11 meant alterations which required a builder’s permit for a new kitchen. The War, however, made renovating very difficult and in the end Georgette had to give up the idea of A.11 and look at a different set instead. On 2 October 1942 she again wrote to Moore, this time with more positive news:

“We are definitely negotiating for a set of chambers in Albany – F.3. This is a very large set, up two long flights of concrete stairs, – rather unfortunately, having one frontage onto Vigo Street. One window only gives onto Albany itself. But it has distinct advantages – & the set I very much wanted can’t have a kitchen put in until after the War, so that was out. I may yet end up there — if I make my fortune with Penhallow!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 2 October 1942.

Lady Lee’s sitting-room in Albany

Lady Lee’s sitting-room in Albany A corner of Lady Lee’s bedroom in AlbanyViews of Lady Lee’s set in Albany with its sumptuous furnishings and decorations.£125 per annum!

A corner of Lady Lee’s bedroom in AlbanyViews of Lady Lee’s set in Albany with its sumptuous furnishings and decorations.£125 per annum!On 24 November 1942, Georgette and Ronald moved into their new home at F.3 Albany. Located on the second floor, their new home had two floors with two main rooms and a bedroom and bathroom on the lower floor and the kitchen on the upper floor. Georgette had her desk and her library set up in the large light-filled sitting room and they ate their meals in the elegant dining room. To reach the kitchen Georgette and Ronald had to navigate a narrow winding staircase – an inconvenience they were prepared to endure if it meant living in Albany. There were also the seventy narrow concrete steps to climb in order to reach their front door but Georgette would manage these for the next 24 years, until ill-health forced her to give up her beloved set. There was so much to love about their new home, not least of which was the remarkably low rent. In 1942 this was a paltry £125 a year! This increased in 1945 to £350 per year and in 1952 until they moved out in 1966, their rent was just £500 per year!

More views of a set in Albany. Georgette’s own set was also elegantly furnished with Regency prints on the wall in the dining room.Richard’s room

More views of a set in Albany. Georgette’s own set was also elegantly furnished with Regency prints on the wall in the dining room.Richard’s roomWhen, in 1942, Georgette and Ronald took the lease for F.3. they also took a lease on a room known as F.1 Attic. Located on the top floor and also known as “F.1 Top” this was a tiny room with a sloping roof and one window that looked out over one end of the Rope Walk and at an angle over Savile Row and Vigo Street. Richard was ten when his parents moved into Albany and, as children under the age of thirteen were not allowed to live in Albany, he had to be given a special dispensation to stay there during the school holidays. It was a lonely place for a child, and for much of his time there, Richard was the only child in residence. He had one confidant in Albany, however, and that was the remarkable man known as the Squire of Piccadilly. William Stone, was a bachelor, a lifelong Albany resident and had been “a bright young dog of the Victorian Age”. Stone owned many of Albany’s sets and when he died in 1958 he willed 37 of these to his alma mater, Peterhouse College, Cambridge. Richard liked William Stone and always remembered the time when the old gentleman had bent down and said, “I was at the Tsar’s wedding you know – not the late Tsar you understand.” Richard was always fascinated that he had had as a friend a man who had been present when Maria Federovna married Alexander III.

View of Albany from the rear. Georgette Heyer’s apartment or ‘set’ was on the second floor to the right of the gate.Macaulay’s ghost and other famous residents

View of Albany from the rear. Georgette Heyer’s apartment or ‘set’ was on the second floor to the right of the gate.Macaulay’s ghost and other famous residentsMany famous people have lived in Albany but its most famous ghost was the historian, Thomas Babbington Macaulay, who moved into Albany in 1840. He originally lived in E.1. where Georgette’s friends the Freres lived, but on 17 December 1846 Macaulay moved to ‘larger chambers at F.3. on the second floor by the gate which leads to Vigo Street’. Here, in the very set which Georgette Heyer would occupy almost one hundred years later, he found ‘more room for his constantly increasing library’ and wrote much of his most famous work: The History of England from the Accession of James the Second. It was in F.3 that his ghost apparently took up residence although Georgette always said that only Johnny the bull-terrier ever took any notice of it! In Georgette’s time other famous residents of Albany included Malcolm Muggeridge, Sir Isaiah Berlin, Alan Pryce-Jones, Sidney Bernstein, Antony Armstrong-Jones, Earl of Huntingdon, J.B. Priestley, Sir Kenneth Clark, Margery Sharp, Sir Harold Nicolson, Prince Littler, Viscount Esher, Graham Greene, G.B. Stern, Clifford Bax, Baron Philippe de Rothschild, Edward Heath, Sir Terence Rattigan (who moved into F2 below the Rougiers in 1946 until 1949) giving way to Clifford Bax in 1949 who in turn gave way to Ted Heath in 1962), Margaret Leighton, Edgar Lustgarten, Patrick Hamilton and Dame Edith Evans. Georgette was not fond of the Edward Heath, the future Prime Minister, because he used to play the piano late at night and keep her awake!

Albany in the early nineteenth century.Albany in fiction

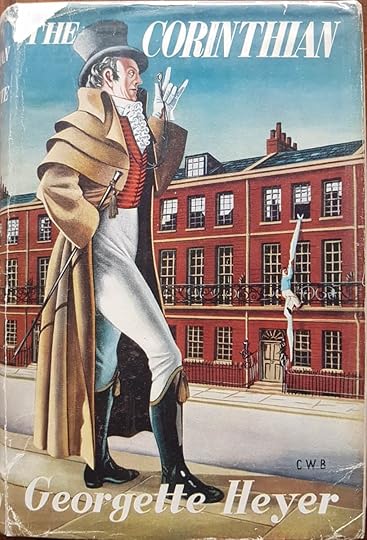

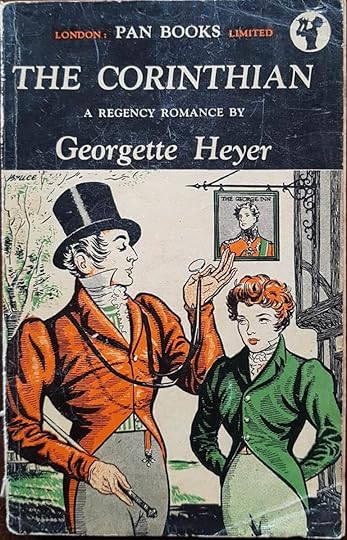

Albany in the early nineteenth century.Albany in fictionAlbany has long been popular with authors wanting the ideal residence for their characters. From Lord Lufton in Trollope’s Framley Parsonage to Disraeli’s Endymion, Oscar Wilde’s Ernest, E.W. Hornung’s gentleman burglar, Raffles, Compton Mackenzie’s soldier bachelor, Prescott, to Georgette Heyer’s Captain Gideon Ware, all have lived in Albany and enjoyed its unique character.

“I live in the Albany,” said Endymion. “You live in the Albany!” repeated St Barbe, with an amazed and perturbed expression. “I knew I could not be a knight of the garter, or a member of White’s – the only two things and Englishman cannot command; but I did think I might some day live in the Albany. It was my dream. And you live there! Gracious!”

Benjamin Disraeli, Endymion, 1880, chapter 51.

“… and the Duke going off to Albany, where Captain Ware rented a set of chambers. These were on the first floor of one of the new buildings, and were reached by a flight of stone stairs. The Duke ran up these, and knocked on his cousin’s door … [Wragby] would have announced him had not Gilly shaken his head, and walked without ceremony into his cousin’s sitting-room. This was a comfortable square apartment, with windows giving on to a little balcony, and some folding doors that led into Captain Ware’s bedchamber. It was lit by candles, a fire burned in the grate, and the atmosphere was rather thick with cigar-smoke. The furniture was none of it very new, or very elegant, and the room was not distinguished by its neatness.

Georgette Heyer, The Foundling, Pan edition, 1967, p.60.

Albany in 1803, the year it was opened as bachelor quarters.

Albany in 1803, the year it was opened as bachelor quarters.

March 5, 2021

The Reluctant Widow – a very funny Gothic novel

Georgette Heyer did not publish a book in 1945. She had been remarkably prolific throughout the 1930s with sixteen published titles in that decade alone. The 1940s, however, would prove to be a decade of change. Although she still managed to publish nine novels between 1940 and 1949, Heyer did not produce a book at all in either 1943, 1945 or 1947. There are several likely reasons for these unusual (for her) gaps in her writing. Illness, war, family demands and a severe paper shortage were all factors, but Georgette was also progressing into middle age and finding it harder to summon the extraordinary energy that had enabled her to write an average of two books a year between 1928 and 1941. It is also perhaps unsurprising that there was no new Georgette Heyer novel in 1945 given that in May of that year the Second World War ended and in September her only child, Richard, began the next stage of his education as a boarder at Marlborough College. The first intimation of a new novel came soon after Georgette had seen Richard off to his new school. She wrote to her friend and publisher at Heinemann, A.S. Frere, to tell him that:

‘There is a book going round in my own head like a borer beetle, but it hasn’t yet chrystalised. Do you like mixed metaphors?’

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 30 September 1945.

The 1946 Heinemann first edition with its plain Wartime jacket.A delightful parody of the Gothic romance

The 1946 Heinemann first edition with its plain Wartime jacket.A delightful parody of the Gothic romanceThe book eventually did ‘chrystalise’ and Georgette was soon once again engrossed in writing her new novel. Another Regency historical, this was to be a delightful parody of the Gothic romance and a book which offered its author plenty of scope for her comic talents. Georgette had grown up reading many of the classics including Jane Austen who was her favourite author. Austen’s novel Northanger Abbey is a clever and humorous parody of the Gothic novels popular in her day and Heyer obviously took pleasure in writing her own humorous Gothic tale. The novel – eventually to be called The Reluctant WIdow – has a compelling and suitably sinister opening. Miss Elinor Rochdale, well-born but penniless and alone in the world, alights from a stagecoach with the expectation of being met by a servant in a gig and transported to her new home, there to work as governess to one Mrs Macclesfield’s ‘high-spriited’ (read difficult) seven-year-old son. When approached by a servant and asked if she is the young lady ‘come down from London in answer to the advertisement’, Elinor agrees and is soon on her way (in an unexpectedly luxurious carriage) to her new home. But all is not as it seems and the house to which she is taken is gloomy and decayed. She is led to the library and there meets the man she assumes to be her employer. A conversation ensues and it is some time before Elinor discovers that she and the man before her have been talking at cross-purposes. Aghast to find herself in the wrong house, she demands to be taken to Mrs Macclesfield’s. Unfortunately, it is by now past a respectable hour for arrival and Lord Carlyon is now bent on persuading Elinor to aid him in a truly Gothic plan. It is Carlyon’s wish that she marry his young and dissolute cousin, Eustace! All of this transpires in chapter one and such is Heyer’s skill that the reader (and Elinor) are not only convinced but amused by the reasons for Carlyons Machiavellian machinations.

The gorgeous 1947 Book Club edition with a cover by noted artist Philip Gough.‘Gothic shenanigans’ and a rare error

The gorgeous 1947 Book Club edition with a cover by noted artist Philip Gough.‘Gothic shenanigans’ and a rare errorGeorgette had great fun creating a suitably Gothic setting for her heroine, the newly wed and newly widowed, Elinor Rochdale – now Mrs Cheviot. Highnoons, the house she inherits from her deceased husband, has long been neglected and its overgrown garden, vine-clad windows, dusty rooms and skeleton staff prompt her heroine to make reference to ‘all of one’s favourite romances’. Heyer, of course, had read the most famous early Gothic novelists such as Clara Reeve, Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe and Monk Lewis and she uses elements of their work such as secret passages, attacks in the night, locked rooms, and foreign conspirators to good effect in The Reluctant Widow. Heyer does make one rare and surprising mistake in the novel, however. when she describes Elinor reading a novel on her first evening at Highnoons. Initially described as a book by ‘Miss Clara Reeve’s story’ Heyer goes on to describe Elinor’s reaction to ‘Orlando and Monimia’s’ melodramatic story. But their story was by Miss Charlotte Smith who published The Old Manor House in 1793. Later in the scene, Heyer does refer to ‘Miss Smith’s Monimia’, so she clearly knew who the author was but accidentally inserted Clara Reeve’s name instead of Charlotte Smith’s at the beginning. Despite this minor error, The Reluctant Widow is replete with the tropes and cliches of the Gothic romance. Elinor, too, is familiar with the Gothic tradition and able to observe to Lord Carlyon in a humorously sarcastic comment that:

‘I expect you will like my new book’‘I hope there may be a blasted oak. I do not ask if a spectre walks the passages with a head under its arm: that would be a great piece of folly! …The house is clearly haunted. I have not the least doubt that that is why only two sinister retainers can be brought to remain in it. I dare say I shall be found, after a night spent within these walls, a witless wreck whom you will be obliged to convey to Bedlam without more ado.’

Georgette Heyer, The Reluctant Widow, Pan, 1961, p.75.

Rosemary Marriott (nee White) as she is today. As a teenager concerned for her favourite author’s well-being, Ro wrote to Georgette Heyer after the War and received kind letters and signed books in response.

Rosemary Marriott (nee White) as she is today. As a teenager concerned for her favourite author’s well-being, Ro wrote to Georgette Heyer after the War and received kind letters and signed books in response.In February 1946, Georgette wrote to a young Australian fan to say that her novel, The Reluctant Widow, would be published in the spring. Knowing teenage Rosemary to be an avid reader of her novels, Georgette said, ‘I expect you will like my next novel’ and went on to thank her for the parcel of food which Rosemary and her mother had sent Georgette from Australia. While Georgette Heyer had a reputation for disliking her fans this was not entirely true. What she disliked were people who gushed over her novels, describing them as ‘sweetly pretty’ or demanded to know ‘where she got her ideas?’. Georgette loved people reading her books and she always answered fan mail that she thought sensible or intelligent, but she was impatient of readers who flattered her or suggested (as one reader did) that a statue be erected in Georgette’s honour. When young Rosemary White from Shepparton in Victoria, Australia, wrote to Georgette out of concern for her well-being on account of the strict food rationing in Engand after the War, her favourite author could not help but be touched. Worried that Georgette might be starving and (unsurprisingly) oblivious to her real circumstances – Georgette was living in Albany and shopping for food at Fortnum & Mason’s and Harrods – for several years Rosemary and her mother sent Georgette and her family food parcels. Each year a parcel would arrive at Albany with a large homemade fruit cake and packets of dried fruit and nuts and Georgette would respond by writing her young admirer pleasant, chatty letters and sending her signed copies of her latest novel. There was much in The Reluctant Widow for Rosemary to love for Georgette had given the hero an endearing younger brother, Nicky, who was guaranteed to win the heart of a romantic teenager. Georgette’s own son, Richard, was fourteen when The Reluctant Widow was published and there is no doubt that he influenced her creation of Nicholas Carlyon.

Georgette Heyer wrote several letters to young Rosemary White in Australia and always sent her a signed copy of her latest novel. The first (but hopefully not the last) Heyer movie

Georgette Heyer wrote several letters to young Rosemary White in Australia and always sent her a signed copy of her latest novel. The first (but hopefully not the last) Heyer movie

‘Miss Wallace tells me that there is a whisper down the chromium and three-ply corridors of what is called the film industry, that Somebody Wants THE RELUCTANT WIDOW.’

Frere to Georgette Heyer, letter, 2 April 1946.

And indeed somebody did. It took another four years but in 1950The Reluctant Widow (The Inheritance in the USA) finally made it to the big screen. Georgette had long wanted her books made into films. From as early as 1925, when she had urged her agent, Leonard Moore, to try and sell a film option for Simon the Coldheart, she had yearned to see the product of her imagination on the silver screen. In 1935 she wished that someone would see ‘what a super film Regency Buck would make’ and in the 1960s she was delighted when Anna Neagle became interested in playing Lady Denville in a film of False Colours. In 1971 she actually sold the film rights to These Old Shades. Sadly, so far, nothing has come of the many options sold to various production companies for a film or series of Georgette Heyer’s wonderful novels. I do not despair, however, for the books are ripe for production into a well-crafted, witty and intelligent film or television series and in many ways this seems more likely now than ever before. The 1950 production of The Reluctant Widow was not a box-office hit but then it diverged so far from Heyer’s clever comic novel that that is probably not surprising. While perfectly watchable (you can see it here) with some fine scenes and a charming opening with a stage-coach, it does not come close to doing Georgette justice. She never saw the film, mainly because her son Richard saw it and was appalled by it. He told his mother ‘don’t go, Mummy, You would hate it’. In fact, the final film is not that bad (for an excellent account of it see Rachel Hyland’s essay in Heyer Society), but Georgette was put off by the advance publicity which she found too salacious:

‘I am being driven frantic by the advance publicity from Durham, and am trying to think what I can do about it. I feel as though a slug had crawled over me. I think it is going to do me a great deal of harm, on account of the schoolgirl public. Already I’m getting letters reproaching me. They have turned the Widow into a “bad-girl” part for Jean Kent, and this week’s Illustrated carries two pages, headed “Jean Locks Her Bedroom Door”. Also seduction scenes 1 and 2. If you can think of any answer, for God’s sake tell me! Smith, of Christy & Moore, is going to try to go down to see the rushes, and hopes we may be able to do something through diplomacy. I don’t think there’s much hope. I should like a notice to appear in every paper disclaiming all responsibility. At all events, I think I can get my name removed from the thing, and I shall. It seems to me that to turn a perfectly clean story of mine into a piece of sex-muck is bad faith, and something very different from the additions and alterations one would expect to be obliged to suffer. If I had wanted a reputation for salacious novels I could have got it easily enough. The whole thing is so upsetting that it is putting me right off the stroke.’

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 30 November 1949.

Valued and esteemed

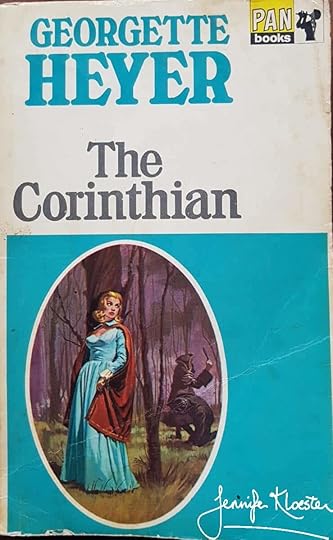

Valued and esteemedIt is a pity that the film of The Reluctant Widow did not do the book justice, especially as Georgette’s novels were so highly valued and esteemed by her publisher and her readers. In 1952, Heinemann in association with Chatto & Windus published a limited series for its ‘Vanguard Library’. The first author to be included in this series was Somerset Maugham, followed by Aldous Huxley, Graham Greene and Compton Mackenzie. Daphne du Maurier was fifth and Georgette Heyer was the seventh author to be added to the list. Heyer’s inclusion re-emphasises the way she was perceived during her lifetime – as a writer who appealed to people across the social and cultural spectrum. While her appeal has not lessened and she is well on the way to becoming a classic author, it is unfortunate that, as Stephen Fry recently pointed out, the covers of her books do not always reflect the wit, the humour and the intelligence of their contents.

In 1952, Heinemann added Georgette Heyer to their library of eminent authors with this edition of The Reluctant Widow

In 1952, Heinemann added Georgette Heyer to their library of eminent authors with this edition of The Reluctant Widow Countless comic moments

Countless comic momentsA light-hearted story with countless comic moments, The Reluctant Widow is also a murder mystery with two deaths and a denouement in which the spotlight is captured by one of Georgette’s most deceptively ruthless and yet utterly debonair characters: the dandy Francis Cheviot. The happy ending is assured, however, and nearly fifteen years later Ronald was forcibly reminded of it in court. In February 1959, at a session of the Water Bill Committee Hearings in the House of Commons (in which Ronald was acting as counsel for the Committee), the Chairman, Major Legge-Bourke, made a speech to the opposing counsel:

The Chairman: Perhaps I might say to you, Lord Vaughan, that while you were using the wedding-metaphors I could not help but be reminded of something with which Mr Rougier is, perhaps, more familiar, from The Reluctant Widow, by Georgette Heyer: “I have spent a great deal of my life listening patiently to much folly. In my sisters I can support it with tolerable equanimity. In you I neither can nor will. Will you accept my hand in marriage, or will you not?”

Lord Vaughan: Mr Rougier has matrimonially the advantage!

House of Commons: Minutes of Evidence taken before the Committee on Group B of Private Bills on the South Bucks & Oxfordshire Water Bill, Bucks. Water Bill, Readings Berkshire Gate Bill, Mid-Wessex Water Bill, Wednesday 4th February 1959.

The 1961 Pan edition

The 1961 Pan edition The 1962 Pan edition

The 1962 Pan edition

February 26, 2021

Georgette Heyer – a new appreciation

The 2021 University College London Press first edtion of academic essays on Georgette HeyerA fascinating collection

The 2021 University College London Press first edtion of academic essays on Georgette HeyerA fascinating collectionIn this, Georgette Heyer’s centenary year, yesterday’s launch of Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction by the University College London Press seems perfect timing. This fascinating collection of essays by academics and independent scholars from the UK, Australia and the USA greatly expands our understanding of Heyer’s literary ouevre, her form of historical fiction, her language, characterisation, and her original and longlasting contribution to the historical novel genre. Nearly fifty years after her death, Georgette Heyer’s more than fifty novels continue to sell and her remarkable longevity continues to attract critical attention. The first serious appraisal of Heyer was in 1966 when the beloved historical novelist Rosemary Sutcliff wrote a long introduction for a special edition of Heyer’s novel of Waterloo, An Infamous Army. The second and by far more enduring analysis of Heyer’s literary prowess came in 1969 when A.S. Byatt wrote a perceptive piece for Nova magazine entitled, “Georgette Heyer is a Better Writer Than You Think”. Since then there has been a growing number of academic theses (both MAs and PhDs), journal articles, newspaper articles and online blogs discussing, analysing and frequently appreciating Heyer’s contribution to literature. In 2001, Mary Fahnestock-Thomas published her marvellous compilation of reviews of Heyer’s novels which also included some of Heyer’s early writing and several articles about Heyer. This invaluable resource has helped to further reader understanding and appreciation of the reclusive bestseller. Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction is the first academic text to focus solely on Heyer and is an invaluable contribution to our understanding of this reclusive but enduring author whose work has been overlooked by serious critics for far too long.

The 2001 edition of this wonderful collection of many things Georgette Heyer.‘The persistence of Heyer’s presence’

The 2001 edition of this wonderful collection of many things Georgette Heyer.‘The persistence of Heyer’s presence’In the editors’ excellent Introduction to Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction, Professor Kim Wilkins and publisher and editor, Samantha Rayner, argue that ‘the enduring appeal of her work signals an importance that we believe should be recognised via more academic study and appreciation of her achievements’ (hear, hear!). They offer this wide-ranging volume of essays as the first serious study of Heyer’s oeuvre and put out the call to ‘researchers from all over the world’ to explore ‘different aspects of her work’. Certainly the thirteen essays on offer in Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction provide Heyer readers with a rich and eclectic intellectual feast, ranging from a discussion of Shakespeare in Heyer, her Regency language, Heyer in science fiction, Heyer’s military novels, the Gothic in Heyer and studies of specific novels such as A Civil Contract and Regency Buck among other commentaries. As they point out in their conclusion, ‘such eclecticism underscores the wide reach of Heyer’s work’ – something all Heyer readers know to be true and a point aptly underscored at the online launch of this valuable new book with attendees from as far afield as Australia, Pakistan, Rumania, Scotland, New Zealand, Britain and the USA.

Samantha Rayner co-editor of Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction

Samantha Rayner co-editor of Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction Kim Wilkins co-editor of Georgette Heyer, History and Historical FictionA feast for fans

Kim Wilkins co-editor of Georgette Heyer, History and Historical FictionA feast for fansI have had a delightful time reading this feast for fans – Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction. Each chapter has enlightened and entertained and several have sparked new and unexpected ways of thinking about Heyer and her novels. Though not usually a science-fiction or fantasy reader (though I love Tolkien, Le Guin, Feist and Pratchett), Kathleen Jennings’s essay “Heyer…in space! The Influence of Georgette Heyer on Science Fiction” inspired in me a strong desire to read more of those genres. A foray into Tor.com was illuminating and many Heyer-influenced titles have now been added to my TBR list! Tom Zille’s essay on “Georgette Heyer and the language of the historical novel” was another eye-opener. I read with deep appreciation his account of how Heyer researched and used Regency slang as well as his analysis of her narrative voice and linguistic style with apparent Austen, Victorian and early twentieth-century historical writers (such as Sabatini and Orczy) all having an influence on Heyer. Despite these influences, however, Tom Zille rightly concludes that ‘The dialogue of the Regency romances is the creation of Heyer alone.’

Kathleen Jennings who pursues Heyer’s influence on science fiction writers

Kathleen Jennings who pursues Heyer’s influence on science fiction writers Tom Zille whose deep dive into Heyer’s language is fascinating readingA few favourites

Tom Zille whose deep dive into Heyer’s language is fascinating readingA few favouritesOne of my favourite essays was Jennifer Clement’s intelligent and insightful account of ’emotional hypocrisy’ in A Civil Contract. Whether you love or hate A Civil Contract (it tends to be a book that grows on readers as they age), Clement’s chapter will give you a new appreciation of this complex and brilliantly constructed novel. A Civil Contract is Heyer’s most realistic book (and one of my absolute favourites) and one which deserves this level of analysis. Geraldine Perriam’s piece on Freddy Standen will both inform and delight all of us who love Freddy and who are interested in Heyer’s various representations of the ‘hero’ in her novels, while Laura George’s clever essay on Judith Taverner as ‘dandy-in-training’ is thoughtful, provocative and well-worth reading. Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction is a true feast for fans and will confirm you in your in belief that Georgette Heyer is, as the editors themselves, pronounce her: ‘a Nonesuch’ – ‘a person or thing without equal’!

‘I think that what makes her so unique is the rare combination of totally gripping stories, historical detail that is spot-on yet illumiinating, characters that are so enjoyabe, romantic storylines that are genuinely heart-stopping and gorgeous and finally and most importantly all wrapped up and told by someone with a cynical eye. She is not fluffy, or prone to flummery…’

Harriet Evans, quoted in Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction, p.8

February 19, 2021

Friday’s Child by Georgette Heyer

!942 was a watershed year for Georgette Heyer. In May she finished writing Penhallow, the novel she believed was ‘a bit of a tour-de-force‘ and in November she and Ronald moved into a set of chambers in Albany in central London. Albany would prove to be a very good move for Heyer, for over the next twenty-four years she would write some of her finest novels there. Penhallow, however, would be the greatest personal disappointment of her writing life. Published in October 1942, it sold out its first print run of 12,500 copies but it did not win her the rave reviews Georgette had been hoping for. It is possible that her disillusionment over Penhallow was one of the reasons why she produced no book in 1943 – a rare absence that had happened only twice before in 1924 and 1927. These were also the War years and challenging times for the British. Although Georgette was stoical by nature something kept her from her writing for well over a year after she had finished Penhallow.

The Heinemann 1944 wartime first edition of Heyer’s bestselling novel, Friday’s Child. The plain wrapper is due to the paper shortage.Very few letters extant

The Heinemann 1944 wartime first edition of Heyer’s bestselling novel, Friday’s Child. The plain wrapper is due to the paper shortage.Very few letters extant1943 was also a year for which there are very few letters extant. There are only nine letters for the entire year, with one written in January and the remaining eight written from August onwards – six of them to her agent and two to her friend and publisher, A.S. Frere of Heinemann. Several of the letters are written from the St Enodoc Hotel in Wadebridge, Cornwall, where Georgette and Ronald and their eleven-year-old son, Richard, were spending several relaxing weeks and where Georgette was apparently convalescing after some sort of illness. The only clue to her long hiaitus from her usual energetic writing lies in a postcard written from Cornwall to her agent, Leonard Moore, which ends: ‘Health better, pen still idle’. She also wrote a cheerful letter to Frere which included a paragraph in typical humorously self-deprecating Heyer-style which reflected her more hopeful state of mind regarding books she might soon write:

Are you at Cape Wrath, & is it fun? With luck, I shall write a thriller for Uncle Percy [her Hodder & Stoughton publisher] while I’m here, & then I can get down to a book for you. It might be Wellington, but quite easily not. Maybe I’ll make some easy money with a frippery romance. You needn’t put on your despising-face, either, because if I do prostitute my deathless art you’ll do very well out of it.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 3 August 1943, written from the St Enodoc Hotel, Wadebridge, Cornwall.

It is not known exactly what Georgette meant by ‘the Wellington book’ but for she had a long-held ambition to write a serious biography and after her work on An Infamous Army and The Spanish Bride she may have had the Duke of Wellington in her mind as a likely subject. Whatever her idea, she never did write a biography. The closest she ever came was her fictional posthumous novel, My Lord John, about the John of Lancaster, which she never finished.

The fabulous St Enodoc Hotel in Wadebridge Cornwall where Georgette Heyer recuperated after illness and began writing again.Illness or disappointment or something else?

The fabulous St Enodoc Hotel in Wadebridge Cornwall where Georgette Heyer recuperated after illness and began writing again.Illness or disappointment or something else?It is possible that earlier in the year Georgette had succumbed to a severe illness or suffered one of her ‘nervous breakdowns. It is also possible that in the months following the publication of Penhallow (October 1942) that her disappointment over the novel’s reception had badly affected her. She had had high hopes for Penhallow, believing her agent and publisher who had each told her it would be a suces fou – an extraordinary success. Unfortunately, although the book did well and earned good reviews, Georgette’s vision of accolades and recognition had not been realised. Whether it was her disappointment, a serious illness or something else that prevented her from writing we may never know. What is certain is that when she finally did begin writing again, it was to be a book that would forever change the course of Georgette Heyer’s career.

The Australian first edition also published in 1944 and reprinted many times afterwards. Australians loved Heyer from the first.Shakespeare and Cophetua

The Australian first edition also published in 1944 and reprinted many times afterwards. Australians loved Heyer from the first.Shakespeare and CophetuaWithin six weeks of her return from Cornwall, Georgette had written 55,000 words of her new novel. She had dispensed with the idea of writing a thriller for Hodder & Stoughton and begun a vivacious historical romance. This would be her 32nd novel but only her fifth book set in the true English Regency – that period between 1811 and 1820 when George III had been declared mad an dhis son, George, Prince of Wales was appointed Regent to rule in his father’s stead. On 12 November Georgette told her agent that she had written about half the book and gleefully explained that

It is very lively indeed – a laugh on every page, & people ought to lap it up. I have a new sort of character in George, Lord Wrotham, who amuses me tremendously. He is a beautiful & turbulent young man, always trying to call his friends out to fight duels, & never succeeding. He’s in love in a very romantic & despairing way with the Beauty, & I’ve got him well & truly embroiled in the Heroine’s affairs too.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 12 November 1943.

Georgette was once again writing at top speed and with all of her usual verve and enthusiasm. At first, she thought of calling the new book Cophetua, after the 16th century ballad about King Cophetua and the beggar-maid. The word “Cophetua” had become shorthand for a man who falls in love with a woman and instantly marries her. The story would have been familiar to anyone brought up on Shakespeare as Heyer was, for the Bard alludes to the tale in several of his plays. Heyer enjoyed using Shakespeare as a source when naming her novels. Unfortunately, neither her publisher nor her agent thought Cophetua a ‘selling title’, so Heyer offered them an alternative: Friday’s Child. She had been a little “dubious about Friday’s Child‘, thinking it too similar to Faro’s Daughter, but both Frere and Moore were enthusiastic. That was good enough for Georgette who told them: “since you both like the title, & it is certainly apt, I’ve decided to use it.'”

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid by Edward Burne-Jones 1883Georgette’s personal favourite

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid by Edward Burne-Jones 1883Georgette’s personal favouriteFriday’s Child was Georgette Heyer’s personal favourite among her many novels. She always said it was because of Ferdy Fakenham, that slightly dim-witted, but very funny, foil to the young and impetuous hero, Lord Sheringham. Ferdy is definitely a stand-out in the novel, not only for his occasional lapses into (for him) deep thinking, but also for his glorious take on Nemesis, the Goddess of Retribution. Heyer’s running joke in the novel has become a byword among Heyer fans and just the mention of the name is enough to provoke laughter among knowing readers. Ferdy is joined in this witty, light-hearted story by his friends: the impulsive hero, Sherry (Lord Sheringham), charming Gil Ringwood, and the handsome, hot-blooded Byronic alpha male, George, Lord Wrotham, while the endearing heroine is the appropriately named “Hero”. She is the “Friday’s Child” of the story and a joy to read. Smitten with Sherry and married on a whim, Hero makes her debut into Polite Society with a glorious naivete that has many unexpected consequences for her young and irresponsible husband. Heyer’s genius for comedy and her mastery of period detail and language is evident throughout as she takes her unlikely couple on a whirlwind ride from London to Bath in a story replete with wit and humour.

The 1946 Book Club edition produced to the “War Economy Standard” which meant thin cardboard covers, small margins and a sepia jacket.A dozen excerpts

The 1946 Book Club edition produced to the “War Economy Standard” which meant thin cardboard covers, small margins and a sepia jacket.A dozen excerptsAs was often her way when she was excited about a book she was writing, Heyer took the time to write out a dozen excerpts from her work-in-progress for her agent. In the case of Friday’s Child the hand-written excerpt ran to three full pages before Heyer ended with the hope that Moore would find the contents amusing and a brief synopsis of whar remained to be written:

Well, that should give you a very fair idea of my quality in this book! I am now going to deal with Sir Montague Revesby’s bastard-infant, & the Betrayed Village Maiden. This little affair, & my incredible heroine’s part in it, effectually puts a stopper on Sherry’s disastrous friendship with Revesby. So it is a Good Thing about the Baby. After that, we shall work up to the final Quarrel between this peculiar couple, leading up to the heroine’s flight to Mr Ringwood – complete with ormolu clock, & canary in a cage – her sojourn at Bath with Mr Ringwood’s grandmother, the arrival in Bath of George, Sherry, the Beauty, & Sir Montague, & then the final mix-up, in which a nice man called Jasper Tarleton is implicated, Sir Montagu does a hurried exit on finding that George is out for his blood (you’ve gathered that George is a crack-shot?), Isabella at last consents to marry George, & Sherry discovers he’s been in love with his own wife for months. Voilà!

It was a joyful letter about what was to be a joyful book and Friday’s Child would mark the birth of the genre that Georgette Heyer created – the most popular historical novel genre that would become known around the world as ‘the Regency’.

Two of several Pan editions of Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novel, Friday’s Child.

Two of several Pan editions of Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novel, Friday’s Child.

February 12, 2021

Penhallow – NOT a contract-breaking book

Myths and legends are pervasive things that, once they take hold of the public consciousness, are almost impossible to remove. For those who read and love Georgette Heyer’s many novels there a couple of myths that have proved very difficult to shatter. One of these is the idea that she did not want her books made into films (so wrong!) and the other is that her 1942 detective novel, Penhallow, was deliberately written as ‘a contract-breaking book’ when it was actually a book she believed in utterly and which she felt compelled to write. Originally called Family Affair, the novel that became Penhallow would be a book that, not only obsessed Georgette Heyer, but was also a book that she, her agent and her eventual publisher believed to be a tour de force. She held the highest hopes for a great success with big sales and excellent reviews and told her agent that ‘if obsession counts FAMILY AFFAIR ought to be amongst my best books.’

The 1942 UK first edition of Penhallow. Its plain wrapper was due to the Wartime paper restrictions.Struck with the idea

The 1942 UK first edition of Penhallow. Its plain wrapper was due to the Wartime paper restrictions.Struck with the ideaGeorgette had first been struck with the idea for the novel in May 1941 when she should have been writing the book that became Faro’s Daughter. As she explained to her agent:

The most amazing & unexpected thing has happened! While I was meditating on Pharaoh’s Daughter, a wholly unwanted saga about a preposterous family called Pendean, who live at Cressy Hall, crept into my mind, & grew, & grew, & grew. Finally, the family tree spread so, & such ramifications grew up that I set it all down, with a genealogical table attached. My dear L.P., I don’t know yet all the details, but Ambrose Pendean was murdered, poisoned, & he was a roaring, Rabelaisian old man, a real patriarch, with roaring Rabelaisian sons, & two who are Lilies of the Field, & a brother who has soft white hands, & collects jade, and a widowed sister with a wig, & foul language, trailing dirty skirts through the vast spaces of Cressy Hall … It seems to me that the thing is called Family Affair, & possibly set in Cornwall. Only you don’t hunt much in Cornwall,* do you, & the Pendeans obviously do. It will be long, obviously, & more of a problem in psychology than in cold detection.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 28 May 1941.

She continued in this vein for another two full pages, describing the rest of the extraordinary family to Moore, before ending her letter with a message for Percy Hodder-Williams, her publisher at Hodder & Stoughton:

Next time Uncle P. gets restive, tell him that this thing burst on me, willy-nilly. I even dreamed about the Pendeans last night! I shall have to keep a note-book for them, as fresh imbroglios keep cropping up, & mustn’t be forgotten.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 28 May 1941.

She was eager to get the book on paper but was committed to writing Faro’s Daughter for Heinemann first. Frustratingly, it would be some months before she began the only one of her novels to ever psychologically obsess her or raise her hopes of extraordinary success. She could not know that Penhallow would change the course of her writing career.

The US 1943 first edition of Penhallow. This was to be Georgette’s last book with Doubleday Doran.Another new home

The US 1943 first edition of Penhallow. This was to be Georgette’s last book with Doubleday Doran.Another new homeIn September 1941 Georgette and Ronald moved again – this time to 27 Adelaide Crescent in Hove, a few miles further west along the Brighton waterfront from Steyning Mansions. Their new home was a small service apartment on one floor of an elegant, curving row of three-storey white terrace houses with views across the sea. Their building belonged to the famous Sassoon family and had a beautiful black and white marble hall with an elegant wrought iron staircase and a handsome drawing room. To Georgette’s great relief there were no cooking facilities. Instead, all the tenants’ meals were brought up to them by staff overseen by Mr and Mrs Banton, who ran the building. Isabella Banton admired Georgette tremendously and later told Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, that she was a ‘marvellous person’ and that ‘there was nothing she didn’t know’. The two became great friends and on one occasion during the War, when there was alarm that Hove was going to be cut off and all of the staff left the building, Mrs Banton took Georgette’s dinner up to her. Unfortunately, she dropped the lot, but Georgette took it all in her stride, helping to clear up the mess and replace it. Long after Georgette and Ronald had moved to London, she and Isabella continued to correspond and would sometimes have lunch together in town. Georgette’s last letter to Isabella Banton was written only a few months before her death in 1974. Years later, Mrs Banton vividly recalled those months in Adelaide Crescent, when Georgette would sit ‘at the side of the fire writing on her lap and living with real people’. These were the Penhallows.

27 Adelaide Crescent, Hove, near Brighton, where Georgette Heyer wrote her dark, Gothic-inspired novel, Penhallow.Penhallow

27 Adelaide Crescent, Hove, near Brighton, where Georgette Heyer wrote her dark, Gothic-inspired novel, Penhallow.PenhallowPenhallow, the novel Georgette would eventually write in 1942, would be unlike anything she had written before or would ever write again. It stands alone in the Heyer canon. Part murder mystery, part family saga, part pschological experiment, when she finally came to write the book about which she had thought for months, Penhallow poured from her pen.

Let me tell you that with the exception of a handful of passages first jotted down in pencil in a rough note-book, as you see it, so it came out of my head.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 29 May 1942

It is a dense, wordy novel, rich in description and alive with the sounds, smells and scenes of Trevellin, the great, ramshackle house on Bodmin Moor in which her large and ‘preposterous family’ – the Penhallows – live. These were the people who came alive for Georgette while she wrote her strange, and strangely compelling, novel. Each servant and family member is fully-fleshed out with all of their anger and resentment, their worries and secrets forming the complex core of the book. One of the things that sets Penhallow well apart from Heyer’s other novels is the sense of unpleasant realism. Today, we would describe the family as ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘toxic’ and it is a testament to Heyer’s skill that this visceral book is not without its humour.

Penhallow is a fascinating psychological study, not only because of its characters, but also because of the way in which it possessed Georgette Heyer’s mind as it did. Jane Aiken Hodge described Penhallow as ‘a strange, grim book’ and that it showed

more signs of strain than can be accounted for by war and trouble with agents or publishers. This was a bad time in Georgette Heyer’s life, the nearest she ever came to a breakdown.

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, 1985, p.66

Aiken Hodge was wrong about Heyer’s mental state – her breakdown had occurred ten years earlier – but she was right in thinking that Georgette had been under strain – at least in the months leading up to her writing of Penhallow.

Bodmin Moor, Cornwall, where Georgette set Penhallow. © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)Arsenic!

Bodmin Moor, Cornwall, where Georgette set Penhallow. © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)Arsenic!Although she had promised Hodder that she would get to work immediately on Family Affair and the novel was burning in her brain, the book languished through November and December 1941. Georgette had been suffering from an unpleasant skin condition and towards the end of October had begun a treatment prescribed by her doctor. Unfortunately, it had only made her worse:

‘Herewith the contract. I haven’t read it, being too ill to care! I have been taking a cure for a skin-complaint – increasing quantities of arsenic. I cannot describe to you the horror–! I have been in bed for a week, wholly unable even to sign my name. Better now, having jettisoned the cure.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 31 October 1941.

It took time to recover from the arsenic treatment and she remained ‘under doctor’s orders’ for some weeks, describing herself as ‘suffering from Aftermath, which includes such oddments as weakened heart, abnormally low blood-pressure, and blurred sight’. Things were no better in the new year, and Georgette still had not begun the novel she longed to write. Ronald’s mother died on 31 December 1941 and the final weeks of her life had caused Georgette deep emotional anguish as she watched her mother-in-law grow

steadily weaker, lying in a coma, and altering under our eyes. You may imagine what sort of time we went through. She died in her sleep, but not before Ronald had been sent for – the day before – on a false alarm, and not before he, I, and her sister were worn to shreds with the anxiety, and the strain of waiting for an end which was inevitable from the start. None of this exactly helped me to recover my health, and I am today a sort of semi-invalid, but beginning at last to feel a little more alive, and able to cope.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 7 January 1941

By March 1942, she still had not begun writing her Cornish saga and told her agent that ‘the Penhallows are seething in my brain, and if only I could have a month’s peace and quiet I could get them down red-hot onto paper.’ Unfortunately, Georgette had not long recovered from an attack of shingles when her young son, Richard, contracted whooping cough, to be followed only a few weeks later by Ronald who succumbed to a nasty case of ‘flu-cum-tonsillitis’. A month’s holiday at Cleeve Hill saw Georgette and Ronald in better health but Richard had not recovered and would not return to school for the rest of term. There is no doubt that these sorts of health and domestic challenges put a strain on Georgette, but I believe that something else drove her to write Penhallow. Years later, her son Richard would suggest that the novel was ‘a catharsis of her family’. It is an interesting idea. Georgette was in her fortieth year and Penhallow may have been a symptom of what has come to be called ‘a mid-life crisis’. She herself often puzzled over the book, not knowing why it obsessed her as it did. She once described the novel as ‘a very peculiar, long and unorthodox story’ and wondered ‘Why on earth did I have to write this disturbing book?’ She had no clear answer. All Georgette knew was that even if it were a ‘mistake’ she had ‘got to write it’.

It’s no use begging me not to write this book: these astounding people have been maturing in my head for months – a sort of saga, which gets added to, and embroidered every day. I know everyone of them intimately. You’ll have to assure Uncle Percy that however repulsive my characters may be, my treatment of them is Pure as Driven Snow. It will be damned funny, too, particularly when Hemingway gets going in the midst of this Cold Comfort Farm circle.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 14 March 1942.

The 2006 Arrow edition of Penhallow

The 2006 Arrow edition of Penhallow The US 1971 Dutton edition of Penhallow “For Frere”

The US 1971 Dutton edition of Penhallow “For Frere”In the end she did not use Inspector Hemingway in the novel but created Inspector Logan, a character she would never use again. The element of detection in Penhallow is in many ways a distraction from the real story and Georgette herself said that ‘Of course, I ought to have given it an eighteenth-century setting, and have ruled out the element of detection, but I can’t do it now: these people ARE, and it’s not a bit of good trying to alter them to fit another period.’ This was not going to be one of her usual country house murder mysteries. In fact, there is no actual mystery for the reader to solve. We watch the murderer commit the crime and see how the tyrannical old patriarch’s death changes everything. Penhallow is intentionally Shakespearean in showing how a desperate act intended to bring about good consequences instead brings only more tragedy in its wake. It is not surprising that Georgette uses a quote from Measure for Measure at the beginning of the book.

She finally began writing Penhallow at the end of March and finished the book two months later at the end of May. Georgette wrote more letters aboutPenhallowi than any other book. Before, during and after its composition she wrote frequently to her her agent and to her friend, A.S. Frere of Heinemann. the letters reflect her growing conviction that Hodder & Stoughton – the publisher to whom she was meant to give this latest book – would not want to publish Penhallow. The opening line alone – ‘Jimmy the Bastard was cleaning boots – she felt would be enough to put off the devout Christian, Percy Hodder-Williams. She was right. H&S rejected Penhallow and Georgette triumphantly offered it to Heinemann. Frere had long been a fan of the novel and eager to publish it, assuring her that it was ‘her best yet’.

Georgette’s personal dedication to her friend and publisher, A.S. Frere of Heinemann

Georgette’s personal dedication to her friend and publisher, A.S. Frere of HeinemannLove or hate PenhallowFor Frere,

From the Obliged Author,

Not because he has not seen enough of it, or because he could not get a copy of it, but because the Author wishes to present him with a token of the gratitude she feels — not only for the encouragement she received from him, but for the patience with which he bore her continued vapourings about this book.

October 26 1942

Georgette Heyer, hand-written dedication on the fly-leaf of Penhallow,, October 1942.

Time has proven that Penhallow is not Georgette Heyer’s best book, but it is a novel worth reading – especially when one knows just how powerfully it obsessed its author. In Madeline Paschen’s brilliant essay, “The Mystery of Penhallow” she gives the reader a kind of ‘before and after’ view of the novel in light of the longstanding myth of it being a contract-breaking book. It was not a contract-breaking book, but perhaps the story became a useful rationale for the only novel to so deeply disappoint its writer after publication. Penhallow had held its author in thrall. She fervently believed it would ‘sweep the board’; that it would make people sit up and take notice. It did not. Penhallow was successful in that it sold well, but it was not the huge bestseller she had believed it would be. She had held such high hopes and had written such eager, confident letters full of ideas and feelings about the book that its ‘failure’ must have hit her hard. Madeline Paschen sums it up well:

I do believe that something crucial happened to Heyer as a writer in that year between the two books [Penhallow and Friday’s Child]. Penhallow, regardless of its critical failure, was a passion project for Heyer, and showed her flexing her writing muscles outside of the genres where she’d already established herself. Whether you love or hate Penhallow (and arguments can be made for both interpretations), what cannot be denied is that it represented a crucial turning point in Georgette Heyer’s career. It deserves much more recognition and acclaim – certainly more than the “contract breaker” role in which it has been unfairly placed in the popular consciousness.

Madeline Paschen, ‘The Mystery of Penhallow’, in Heyer Society: Essays on the Literary Genius of Georgette Heyer, Overlord Publishing, 2018

* People do hunt in Cornwall, though not as much as in some other counties. Today there are four main hunts in Cornwall: the Four Burrows Hunt at Carn Brea, the Western Hunt at Madron, the Cury Hunt at Helston and the North Cornwall Hunt at Camelford.

February 5, 2021

Faro’s Daughter – written straight to the typewriter!

The gorgeous 1941 Heinemann first edition jacket for Faro’s DaughterFrom house to flat – the move to Brighton

The gorgeous 1941 Heinemann first edition jacket for Faro’s DaughterFrom house to flat – the move to BrightonJust before Christmas 1940, Georgette and Ronald, with their eight-year-old son, Richard, left Blackthorns, their home for the past seven years, and moved to Brighton. Heyer had written a dozen successful novels at Blackthorns but the Second World War had changed many things and she and Ronald could no longer cope with such a large house. She had grown up in a world where domestic servants were an unquestioned part of life and, as an author and the mother of a young child, servants had been a vital support – allowing Heyer to write for as often and as long as she needed without having to think about cooking or cleaning or childcare. One of the most lasting changes brought about by the War was the dramatic shift in employment – especially for women. Many housemaids, cooks and housekeepers were easily tempted away from the drudgery of domestic service to the better-paid-with-better-hours work on offer in factories, public transport or on the land. With bombs falling on Sussex with nerve-wracking regularity, Georgette and Ronald had decided to send Richard away to the Elms, a boarding school in the much safer Malvern Hills. His absence during term time enabled them to move into a service flat with meals provided and regular cleaning. Georgette would be able to manage the household without the need for a maid or cook-housekeeper. On 19 December 1941, the Rougiers began the next phase of their life in a service flat at Steyning Mansions opposite the sea at Brighton.

A 1941 advertisement for Steying Mansions. It was to here that Georgette & Ronald moved in December 1940.A new historical romance…

A 1941 advertisement for Steying Mansions. It was to here that Georgette & Ronald moved in December 1940.A new historical romance…By April 1941, Georgette was well settled into her new home with plenty of time to write. Meals were provided, Richard was safe at school and, when not performing his duties as ‘Gas Company Instructor, Bombing Instructor, & No. 1 Sniper’, Ronald was commuting daily by train to his chambers in London. She was now coming to the end of Envious Casca, her latest murder mystery for Hodder & Stoughton, and had already had an idea for her next book. A.S. Frere, her friend and publisher at Heinemann (now doing War work for Ernest Bevin), had recently been to stay and Georgette had told him that she would have a new historical romance ready for Autumn. Frere had been enthusiastic and urged her to have it ready by the ‘End of August, latest.’ Georgette had agreed, at which point he had immediately said, ‘What I really meant, was the beginning of August.’ Her reputation for producing quality work quickly had become well-known in the firm, but even for Georgette the beginning of August seemed too tight a deadline, and she firmly told Frere, ‘nothing doing’. Two weeks later, her idea for the new book had begun to crystallize and she wrote to her agent to say: