Jennifer Kloester's Blog, page 7

October 9, 2020

From Behold, Here’s Poison to The Talisman Ring

The first edition jacket, Hodder & Stoughton 1936

The first edition jacket, Hodder & Stoughton 1936 The first edition jacket Heinemann 1936Georgette Heyer published two novels in 1936, both with vivid characters but with very different detective stories!

The first edition jacket Heinemann 1936Georgette Heyer published two novels in 1936, both with vivid characters but with very different detective stories! Trying to write Behold, Here’s Poison

In Novembr 1935, Georgette, Ronald and Richard moved out of Blackthorns and into a house called “The Paddocks” in the village of Broadbridge Heath near Horsham. It was a temporary move, made necessary by their decision to renovate Blackthorns, even though they did not own the house but rented it. Georgette was desperately trying to finish Behold, Here’s Poison, but by the end of November, to her great chagrin, she had made almost no progress. As she explained to Miss Perriam: “I have been thrown out of gear by my chosen poison being no good, & it has taken me a lot of time to find a substitute.” She was also in a quandary over money, for the cost of new carpet, lights, furniture and furnishings was proving to be far more expensive than she had anticipated and Georgette was afraid that she would soon be “at my wit’s end for ready cash”. They were living on an overdraft and she was trying to decide if she should continue writing short stories for magazines like Woman’s Journal or stick with the novel. Georgette would have loved to see one or more of her novels made into a film and had hopes that a film company might buy an option on Regency Buck, but once again she was disappointed.

“Why the blazes not one of those stinking film companies can see what a super film Regency Buck would make beats me…I despair of films – I expect Fate is going to be ironic, & i shall sell them when it doesn’t really matter much.”

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 25 November 1935.

Georgette always hoped to see Regency Buck made into a film.

Georgette always hoped to see Regency Buck made into a film. Despite always wanting her books made into films, Heyer was deeply disappointed in the 1949 version of The Reluctant Widow

Despite always wanting her books made into films, Heyer was deeply disappointed in the 1949 version of The Reluctant WidowGeorgette’s “Unavoidable Domestic Difficulties”

Heyer was determined to complete Behold, Here’s Poison before the move back into Blackthorns on 16 December. Two days after writing so pessimistically to Miss Perriam about her struggles with the book. she wrote again much more optimistically to report that, “Behold, Here’s Poison is going along nicely”. Georgette had made “no less than 3 false starts” with the novel, all of which she had torn up. Since then, however, she had written 10,000 words of “Promising Stuff”. Once she got going, Heyer usually wrote with extraordinary facility and in the first few decades of her career generally had no difficulty in finishing a 100,000 word manuscript in six to eight weeks. Behold, Here’s Poison, however, was not to be one of those books. Her aim to have it to Hodder & Stoughton by Christmas proved impossible due to “unavoidable Domestic Difficulties” and Georgette’s remarkable admission that

“after my breakdown last year I daren’t sit up all night writing any more. 5.30 a.m. is now my limit”

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 11 December 1935

It cannot have been easy living in temporary quarters at The Paddocks while supervising the building and renovation works at Blackthorns and attend to Ronald’s and Richard’s needs while trying to write several short stories and a novel in order to alleviate her money worries. Nor can it have helped that The Paddocks was

“like a refrigerator. Three outside walls to the sitting room, two lots of windows, & one French window. Such a delightful summer house, as all my guests remark.”

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter 27 November 1935.

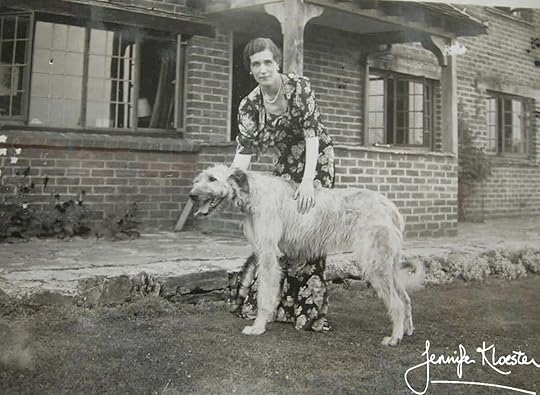

Georgette Heyer and her stately wolfhound

Georgette stopped writing over Christmas and put her money worries to one side. Her friend Joanna Cannan had been in touch with the happy news that she’d found a pedigree wolfhound at an affordable price.

“One charming thing has happened: I look like getting a wolfhound for a song. Been offered a champion-class puppy for £2.2.0, because she’s dislocated her leg, & it isn’t now quite straight – thus making her useless for show…Her name is Misty Dawn, & you can’t deny that I should look well with a stately wolf-hound at my feet!”

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 27 November 1935.

Georgette was elated at the prospect of another dog to join her adored Johnny the bull-terrier and Puck the Siamese cat and she travelled up to Henley to see her likely new pet. The breeder was Miss Esther Croucher, a noted European wolfhound judge, owner of the Rippingdon Kennels at Woodcote, and, from 1939, secretary of the Irish Wolfhound Club. Georgette was smitten with Misty Dawn who stood 33 inches at the shoulder and in later years Georgette would sometimes jokingly threaten to make a scene by bringing her wolfhound with her to lunch at the Ritz.

“the wolfhound wasn’t just any dog. The Irish wolf dog was the hound of kings and warriors dating back to the beginning of Ireland itself, world-famous for its ferocity, prowess in the hunt and —not the least — for its near-human qualities.”

Bob McMillan, 27 March 2018, https://thewildstare.com/what-was-the...

Georgette Heyer with her beloved wolfhound Misty Dawn in the garden at Blackthorns.

Georgette Heyer with her beloved wolfhound Misty Dawn in the garden at Blackthorns. A photo sent by Julie Hughes, an Irish Wolfhound afficianado. It is believed that this is Georgette Heyer with Misty Dawn.Acquiring Misty Dawn was a welcome distraction from her “domestic difficulties” and financial struggles.

A photo sent by Julie Hughes, an Irish Wolfhound afficianado. It is believed that this is Georgette Heyer with Misty Dawn.Acquiring Misty Dawn was a welcome distraction from her “domestic difficulties” and financial struggles.The Talisman Ring – “a wholly glorious novel”

A fortnight after Christmas, Georgette finally returned to her desk and managed to write 7000 words in a single day. By 4 February 1936, the manuscript of Behold, Here’s Poison was complete. It had taken her less than three months to write the novel, but she still apologised to her agent for having “been so long over it”. Even before she had finished it, Heyer was already thinking about what to write next. She’d begun planning a book about Waterloo, but a few weeks later thought she might write some more short stories first – including one called “Corinthian”. By mid-March her money worries had become so severe that she had concluded that the best thing to do was to “abandon – or at any rate postpone – the Waterloo book, & instead to write a light, saleable Regency novel”. She planned to call the novel “Corinthian” and promised to let Miss Perriam “have a synopsis & some 6 or 7 chapters as soon as possible”, but three weeks later she still had not delivered them. Then, on 2 April 1936, Georgette had a breakthrough:

After several days brain-racking, during which time it appeared to me that I had Written Myself Out & couldn’t think of any plot at all, a Wholly Glorious Novel burst upon me in the space of twenty minutes. Three hours work filled in the rough sketch, & the result is the accompanying synopsis, [not attached – unfortunately!] which I hope may convey something to you. I start work tomorrow, & shall hope to have a fair wog to send you by the 14th. Anyway, I send a synopsis now. Unless I’ve lost my gift for the Farcical, which I do not think, I’m going to perpetrate one of my more amusing & exciting works. The title is The Talisman Ring

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 2 April 1936.

The Talisman Ring original cover art

The Talisman Ring original cover art

October 2, 2020

Fifteen years on – Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

It was such a thrill to receive the cover image for

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

. I’ll never forget that moment of first seeing it!

It was such a thrill to receive the cover image for

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

. I’ll never forget that moment of first seeing it!A delight to write!

It seems incredible that this week marks the fifteenth anniversary of the publication of my first book, Georgette Heyer’s Regency World. It was such a delight to write and how much I enjoyed researching it! My love of Georgette Heyer’s many novels began in 1985 when I discovered These Old Shades in the tiny YWCA library in our remote town in Papua New Guinea. But the idea for a companion to Heyer’s novels happened while I was living on the island of Bahrain in the Arabian Gulf. It was an idea born of a conversation with an American friend to whom I had recently introduced Georgette Heyer’s historical novels. She loved them and we spent many happy hours discussing the books and trying to work out which were our favourites (an impossible question with an ever-changing answer!). At times we both expressed a wish for a book that would explain some of the things in Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels that we did not fully understand, could not imagine or with which we were only vaguely familiar. Things like Regency dress, snuff-boxes, carriages, town and country houses, the social hierarchy, Cribb’s Parlour, the Fives-Court, Rotten Row, manners and etiquette, famous people, and a host of other Regency ephemera that we longed to be able to visualise and understand in all their rich detail. Although Heyer’s writing is so good that the reader generally gets a sense of what is meant or looks like or how it operates, we yearned for more detail.

A cutaway view of a tonnish Regency townhouse with the servants’ quarters on the very top floor. One of the illustrations in

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

.

A cutaway view of a tonnish Regency townhouse with the servants’ quarters on the very top floor. One of the illustrations in

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

.Regency research

In 1997 I returned home from the Middle East and immediately began working on what I then thought of as a “Georgette Heyer Handbook”. I had no clear idea of its structure or layout or whether it would ever be published, but I knew there were many things in Heyer’s novels that inspired me to find out more. I began re-reading her novels in chronological order, beginning with The Black Moth. In the earliest days of my research my idea for the reference guide was to include all of Georgette Heyer’s novels but that proved an overwhelming task and after several months I began to focus solely on her 26 Regency novels. I created an index card system for each novel, its characters, places and historical elements. I also created an alphabetised set of index cards for anything in her novels that I thought might be unknown or unfamiliar to modern readers. For example, under “A” were things like Angouleme bonnets, Astley’s Amphitheatre, abigails, Almack’s and Angelo for fencing.

An illustration from Domenico Angelo’s The School of Fencing, with a General Explanation of the Principal Attitudes and Positions Peculiar to the Art.

An illustration from Domenico Angelo’s The School of Fencing, with a General Explanation of the Principal Attitudes and Positions Peculiar to the Art.The wonderful British Library

My card files and notebooks grew and grew and then, in 1999, I was lucky enough to go to London for a special event and, while there, I paid my first visit to the British Library. It is still one of my favourite places on earth and I’ll always remember being given my first British Library membership card. It was like a Golden Ticket that opened the door to a magical kingdom. The Rare Books and Music Reading Room became like a second home whenever I was in England as did the Newspaper Library at Colindale. On that first visit I found myself near to tears when the librarian handed me a copy of the 1787 edition of Domenico Angelo’s The School of Fencing, with a General Explanation of the Principal Attitudes and Positions Peculiar to the Art. could hardly believe that I was actually be allowed to handle and read a 200-year-old book and one that I knew Heyer had read (though perhaps not that exact same volume) and from which she had drawn much of the fencing practice and terminology which so greatly enhanced her historical novels.

The wonderful British Library, home to more than 200 million items. I’ve spent hundreds of happy hours there.

The wonderful British Library, home to more than 200 million items. I’ve spent hundreds of happy hours there.Extraordinary encouragement

For a long time I told no one about my research project, but one day my former history lecturer invited me to lunch at the university. After 13 years of study, mostly doing one subject a semester in either Papau New Guine or Bahrain, I had finally finished my BA. My favourite history lecturer, Roy Hay, had been a great mentor and I’d learned a huge amount about essay-writing and 19th-century British history from him. Over lunch, for some reason, I told him about my Georgette Heyer Handbook idea. He sat back in his chair and looked at me for several long seconds. I remember thinking he’s going to tell me to “stop wasting my time and go and get a job.” Instead, after a long silence he suddenly leaned forward, looked me in the eye and said, ‘That’d make a fantastic PhD!” It was such a surprise, but in that moment I had an epiphany. A sudden, unexpected, never-before-thought-of vision of me in a puffy hat! As a result of that conversation and with Roy Hay’s encouragement, I enrolled in Honours, took a first, and applied to do my Doctorate on Georgette Heyer: Writing the Regency. History in Fiction from Regency Buck to Lady of Quality 1935-1972. It was an incredible feelng when the University of Melbourne offered me a scholarship to do my PhD and in February 2001 I began seriously researching Georgette Heyer’s life and writing.

Puffy Hat Day (PhD)

In March 2005, I was proud to graduate PhD from the University of Melbourne. I had a copy of Georgette Heyer’s first Regency novel, Regency Buck, with me duirng the ceremony. My fabulous mentor, Roy Hay, joined the academic procession.

In March 2005, I was proud to graduate PhD from the University of Melbourne. I had a copy of Georgette Heyer’s first Regency novel, Regency Buck, with me duirng the ceremony. My fabulous mentor, Roy Hay, joined the academic procession.Amazing archives

Doing a PhD meant three and a half years of focussed research and I still think of it as an incredible privilege. Within a few months of beginning my Doctorate I had written to Georgette Heyer’s son, Sir Richard Rougier, and to her biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, and received invitations to visit them when next I was in England. Sir Richard also gave me copyright permission to have his mother’s letters to her agent (1923-1944) copied and sent to me from the repository at the McFarlin Special Collection at the University of Tulsa, USA. Those letters were the first of several new archives of Heyer letters to come to light during my years of research and I have always been so grateful to all those who made access to them possible.

The “Tulsa Archive” with copies of some 600 pages of Georgette Heyer’sletters, still in the box they came in on that memorable day in February 2002.

The “Tulsa Archive” with copies of some 600 pages of Georgette Heyer’sletters, still in the box they came in on that memorable day in February 2002.A dream come true!

Through my years of research I had not forgotten my idea for a “Georgette Heyer Handbook”. Indeed, my PhD had been a vital part of expanding my research as well as a wonderful entrée to libraries and archives that I would not otherwise have been easily able to access. Not long after my graduation, Roy Hay once again took a vital hand in my writing journey. I’d heard that Random House UK were planning to republish all of Georgette Heyer’s available novels and I wondered if they might be interested in my project. Roy emailed a former student of his who worked at Random House in Sydney and told her about my PhD and my idea for a Heyer companion, she forwarded his email to Random House in London, who immediately sent a message back asking me to contact them. I made that exciting phone call, which resulted in a request for a book proposal. I put one together, sent it off and ten days later, Random House offered me a contract for Georgette Heyer’s Regency World. It was an incredible, exciting, dream come true!

Signing copies of

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

in Hatchard’s famous bookshop on Piccadilly

Signing copies of

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

in Hatchard’s famous bookshop on PiccadillySo much fun!

An eloping couple in a post-chaise

An eloping couple in a post-chaiseThere was a lot of wish-fulfillment in writing Georgette Heyer’s Regency World because I was finally able to spend the time discovering many more of the details of the Regency period; all those things about which both Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen wrote with such ease. Austen because it was her world, and Heyer because she knew and loved Austen’s novels and because her own knowledge of the era was so good. One of my favourite chapters in Georgette Heyer’s Regency World is called “Getting About”. I’d always wanted to know what a high-perch phaeton looked like and a how a post-chaise worked with only a rider instead of a coachman to drive it. And what about a barouche? Jane Austen mentioned barouches in her novels and in Pride and Prejudice Lady Catherine de Bourgh is incredibly patronising when she offers Elizabeth Bennet a seat in her barouche. It was so much fun finding out about coaches and carriages and pedestrian curricles. I even had my wonderful illustrator, Graeme Tavendale, create a picture of two women in a high-perch phaeton, drving tandem down St James’s Street, because I’d always wanted to see Sophy Stanton-Lacy with po-faced Eugenia Wraxton beside her. So many of my mental visions came into being thanks to Graeme Tavendale.

One of the illustrations for

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

. I had great fun conceiving the drawings and directing my wonderful illustrator, Graeme Tavendale to create the images for my book.

One of the illustrations for

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

. I had great fun conceiving the drawings and directing my wonderful illustrator, Graeme Tavendale to create the images for my book.Jane Austen’s Ghost

Perhaps it was inevitable that, having spent so many years researching Georgette Heyer, reading her novels and letters, writing articles and books and giving talks about her, I would eventually write my own Regency stories. The first of these is as much inspired by Jane Austen as it is by Georgette Heyer’s Regency world and I adored writing it. Jane Austen’s Ghost is a contemporary novel but with a Regency twist. It’s great fun but for those in the know it has all the invisible foundation of my years (and years) of research and reading. I loved bringing Jane Austen into the modern world and I loved writing the Regency letters that form the backdrop to the story. My next Regency tale is a novella called Priscilla Meets her Match. It will be out in time for Christmas.

September 25, 2020

Behold, Here’s Poison – “An ingenious poisoning device”

The American first edition dustjacket published by Doubleday Doran for their Crime Club series in 1936

The American first edition dustjacket published by Doubleday Doran for their Crime Club series in 1936Georgette had enjoyed writing Death in the Stocks (1935), but it had been her last book for Longmans. She had signed a new contract with Hodder & Stoughton, the publishers famous for their “yellow jacket” books which featured many of the iconic writers of the day. She had every intention of starting the new detective novel as soon as she’d finished with Regency Buck but in June 1935 she wrote to her agent’s assistant, Norah Perriam, to say that the new book would be delayed as she had been ill and was struggling to recover:

‘Neither pen nor paper inspire me with anything but complete mental paralysis’

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 21 June 1935.

At the end of June 1935 Georgette and her family left Sussex and headed north. Her illness had been some kind of “internal poisoning” and she had suffered a complete physical breakdown. She desperately needed a holiday, so they had booked two weeks at the Victoria Hotel in Bamburgh, Northumberland. It was a small village just behind the dunes of a glorious sandy beach and only a short walk from historic Bamburgh Castle. It was an idyllic destination and the Rougiers spent their days exploring the coves and inlets of the north-east coast, taking walks along the beach, shrimping, and paddling in the sea. Although she had “one or two definite ideas about the thriller” Georgette was content to let them bubble away in the background, and made no attempt to write while on holiday. Instead she thoroughly enjoyeda much-needed respite from the demands of producing two books a year.

The Victoria Hotel, Bamburgh, where Georgette Heyer recovered from her illness in 1935. By PookieFugglestein – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The Victoria Hotel, Bamburgh, where Georgette Heyer recovered from her illness in 1935. By PookieFugglestein – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...Recovering from a breakdown

ALthough Georgette spent time with Richard during their fortnight in Bamburgh, he was an energetic three-year-old. To ensure they had a little peace and quiet, the Rougiers brought Richard’s nurse on holiday with them. After a fortnight together in Bamburgh, his parents left Richard in his nurse’s care at the Victoria Hotel and set off for a week in Scotland. This was Georgette’s first trip to Scotland and she loved every minute of it. It was as she said, “a heavenly week” for she’d never “dreamed of such beauty”. They visited St Andrews, where Ronald indulged in “An orgy of golf”, then drove on to Inverness, with a side trip to Loch Rannoch. From there they ran south along Loch Ness to Fort William, before driving on to Lochaber and the pretty port town of Mallaig. Georgette loved seeing Glenfinnan and recalling the stories her father had told her of Bonnie Prince Charlie raising the standard and looking “over the sea to Skye”. By the time they returned to Bamburgh via Berwick she was thoroughly rested and ready to return home and start writing again.

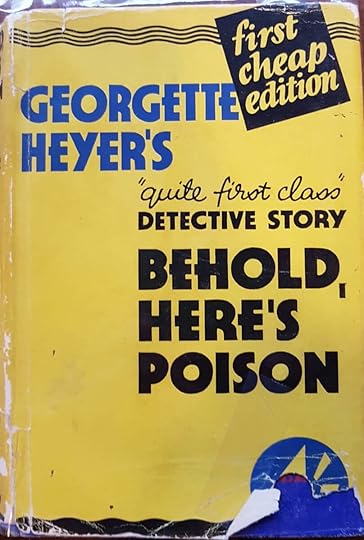

The 1936 first edition of

Behold, Here’s Poison

, Georgette’s first novel with Hodder & Stoughton

The 1936 first edition of

Behold, Here’s Poison

, Georgette’s first novel with Hodder & StoughtonA Shakespearean title

By the end of August she’d made a start on the new detective novel, but when asked by her agent for a title and an outline, she had not yet set it in stone.

‘Rather a teaser. I do know more or less what the new book is about, but I haven’t given it a title, & the plot, being still fluid, is liable to change.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 29 August 1935.

It was at this point that Georgette laid down her pen and took up her Concordance to Shakespeare. After a few minutes perusal, she decided to call her new book either “Timeless End” from Romeo and Juliet, or “Behold, Here’s Poison” from Pericles. Her preference was for the latter and, having decided that two of her characters were to be poisoned, she opted for the quote from Pericles. End the end it was an extremely apt title, for the poison and the method of delivering it may be said to have been under everyone’s eye from the beginning. No spoilers, however, and Behold, Here’s Poison is as much a book about human nature as it is a clever mystery. Heyer obviously enjoyed writing the book, for she gave full rein to her penchant for humour in it by bringing together a cast of very human acharacters, none of whom have any difficulty speaking their minds or being rude either to each other or to the police.

Miss Heyer’s description of family life would win the approval of Mr. G. B. Shaw, so thoroughly does she agree with his thesis that it consists chiefly of a competition in rudeness.

E.R. Punshon, “The Omniscient Detective”, The Manchester Guardian, 23 June 1936.

The 1938 edtion

The 1938 edtion The 1939 editionTwo of the Hodder & Stoughton “Yellow jacket” editions of

Behold, Here’s Poison

.

The 1939 editionTwo of the Hodder & Stoughton “Yellow jacket” editions of

Behold, Here’s Poison

.“The beauty of the book is its wit”

The body is found on page six and by the butler, who clearly did not do it. This delicious reversal of cliche is only the first of many jokes that Miss Heyer plays in the novel. The victim, Gregory Matthews, was the head of the family but he was not well-liked. His umarried sister, Harriet, who lives with him is parsimonious and self-pitying ond insists on telling anyone who will listen that Gregory ought never to have eaten the duck and that no one can blame her because she ordered cutlets for dinner. Her widowed sister-in-law, Mrs Zoe Matthews, also lives with them and she is one of those who must always be at the centre of atention. Mrs Matthews’ son guy is weak andself-indulgent and it is left to his intelligent sister Stella to try to keep the peace. The setting is a large house on Grinley Heath (which Georgette explained was really Wimbledon) into which come Georgette’s two detectives, Superintendent Hannayside and Sergeant Hemingway. The detectives are both capable and clever, and in this, their second novel, they each expand on their very different approach to detection.

‘my favourite Mrs Heyer for a sparkling novel crystallised around a thread of crime…Mrs Heyer had me guessing in Behold, Here’s Poison. She has such a zest for characterisation that she is hard put to it to deodorise a murderer…anyone who can appreciate a delightful book will take it and like it.

Ralph Partridge, “Detective Dozen”, The New Statesman and Nation, 20 June 1936.

Pan edition (1949)

Pan edition (1949) Number 4 in Heinemann’s reissue of Heyer’s detective novels (1954)

Behold, Here’s Poison

was reprinted 7 times in its first three years

Number 4 in Heinemann’s reissue of Heyer’s detective novels (1954)

Behold, Here’s Poison

was reprinted 7 times in its first three years“An amiable snake”

But in the end it is Stella’s clever cousin, Randall Matthews, who takes centre stage and who works out who the poisoner is just a little ahead of the police. Randall is one of Heyer’s sardonic yet compelling men. Intolerant of stupidity, a superb dresser, a man of impeccable taste, independently wealthy, he is also “an amiable snake”. At least that’s how Stella describes him. Randall is Gregory Matthews’ heir and appears to have reason enought to kill him, but nothing shakes Randall’s unshakeable demeanour. He is suave, incisive and generally disliked by most of his family – and he is known to reciprocate the feeling. Heyer gave him some marvellous lines and many readers adore him despite – or perhaps because of it. Georgette is writing her way towards a character who would apear in different guises in some of the Regency novels to come.

‘Randall Matthews, “Amiable snake” dominates entire dazzling yarn, which is a marvellous mélange of malice, murder, mystery, and mirth. – Verdict: Priceless!

“The Criminal Record. The Saturday Review’s Guide to Detective Fiction”, The Saturday Review 14, 5 September 1936, p.18.

The 2006 Arrow edition

The 2006 Arrow edition

September 18, 2020

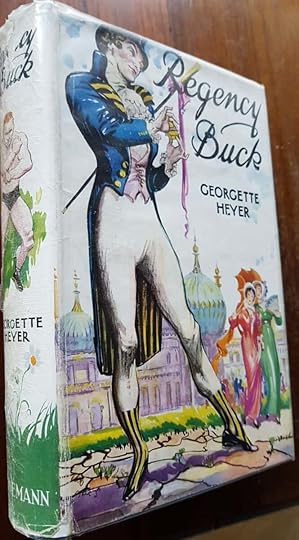

The first Regency novel – Regency Buck

The original 1935 Heinemann dustjacket for

Regency Buck

The original 1935 Heinemann dustjacket for

Regency Buck

“It ought to be a lovely book”

In March 1934 Georgette Heyer began what would become her nineteenth novel. It would also be her first book set in the period of history known as the English Regency – the era when King George III had been declared mad and his son, George, Prince of Wales, would rule as Regent in his father’s stead. Although it lasted only nine years, from 1811 to 1820, the Regency was a dynamic and hugely influential period in British history. While it would be another ten years before she focussed solely on writing books set in the period – and Heyer did not know it at the time of writing Regency Buck – the novel would mark the beginning of a new genre of historical fiction. Georgette was enthusiastic about the book for she had found a wealth of inspiring new material relating to the period and was reading widely. Living in Sussex meant she was in easy reach of London by train and Georgette would sometimes visit the city to have lunch with her agent, shop or visit the London Library. She had been a member of the privaate subscription library in St James’s Square since 1925 and had often had parcels of books sent to her when she was living overseas. Now its wide-ranging collection yielded a rich crop of Regency-related subjects. Georgette immersed herself in the material before writing confidently to her agent:

‘I’m going to open Regency Buck with a Prize Fight – probably Cribb’s second battle with Molyneux, at Thistleton Gap. O.K.? I’ve read Annals of the Ring & Pugilistica – & I know a bit about it now, I can tell you. There will also be a bit of cocking, possibly a meeting of the Beefsteaks, certainly a coaching race to Brighton & a street mill. It ought to be a lovely book.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 18 March 1934

Although the cover stayed the same for many years, the pugilist on the spine only appeared on the 1935 first edition

Although the cover stayed the same for many years, the pugilist on the spine only appeared on the 1935 first editionResearch riches

It was ‘a lovely book’ in some ways, although she did not achieve the subtle distillation of historical detail into the story or create one of her famous imbroglio endings as she would in later novels. Regency Buck is an entertaining story which gives readers a vivid introduction to upper-class Regency London and Brighton in 1811 and 1812 and has several clever portraits of historical personages including Beau Brummell, Lord Alvanley, the Prince Regent, and his brothers, the Royal Dukes. The book is not without its faults, however, for Georgette’s enthusiasm for the period and her delight in the discovery of so much rich material inspired her to use more in this book than she ever would again. Although the story moves swiftly enough, there are moments when the ephemeral detail threatens to engulf the simple central plot. As she had promised, Georgette included all of the things she had mentioned to Moore and added several others, including an encounter with Beau Brummell at Almack’s, an evening at Vauxhall, a meeting of the Four-Horse Club, and a week at Belvoir Castle with the Duke and Duchess of Rutland. Jane AIken Hodge offered an astute assessment of Regency Buck:

‘elated with her own research, she introduced almost too much detail of journeys and furniture into Regency Buck, but came out strong with the Brighton road when Judith Taverner shocked her world by racing her curricle down it, or a cockfight at which her brother Peregrine could get into trouble. And when she wanted a Royal Prince to fall in love with Judith, there was the Duke of Clarence, ready in her notes, with his famous remark about the Thames: “There it goes, flow, flow, flow, always the same.” She devoted almost two pages to the Pavilion at Brighton, which makes her heroine feel faint, and no wonder. Always her own most acute critic, she would not use quite so much background detail again, until it began to creep back in during the last years of her life.’

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, 2nd edition, p.54

The Brighton Pavilion, photo by Jonas Magnus Lystad – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The Brighton Pavilion, photo by Jonas Magnus Lystad – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...Three rare errors

Her enthusiatic research among the sources available at the time resulted in three of Heyer’s rare errors of historical fact. The main one relates to the Brighton Pavilion which she describes in all its Chinoiserie magnificence. But Georgette had set Regency Buck in 1811 and 1812, following the chronology established by R.W. Chapman in his famous annotated Pride and Prejudice, whereas the Pavilion in the form that Heyer describes was not actually begun until 1815 nor finished until 1823. She had always endeavoured to familiarise herself with the different periods in which her books were set and to gain a good general grasp of the social and cultural realities of the time and her mistakes in Regency Buck came from her reading of the limited source material. In 1934 were only four published books about the Pavilion. Heyer’s main source was Lewis Melville’s 1909 book, Brighton: Its History, Its Follies, and Its Fashions which included Brayley’s 1838 Account of the Pavilion. She based her description of the Pavilion’s rooms on Brayley and her confusion over chronology likely arose from an inaccurate reading of his text. In his Account of the Pavilion Brayley describes two dates (1811 and 1784) which are carved into two cornices in the Pavilion. In the book Heyer read, the dates are in bold black print and stand out like sub-headings: H.R.H. GEORGE P.W. a.d. MDCCCXI and H.R.H. GEORGE P.W. a.d. MDCCLXXXIV. It appears that she assumed the descriptions written beneath these headings related to those dates. Her second mistake was in attributing the grand oriental design of the Pavilion to Henry Holland who, in 1787, had overseen the original conversion of a farmhouse into the Marine Pavilion, rather than the architect John Nash. This error also came from her misreading of Brayley’s Account. Heyer’s final error in Regency Buck was to have her heroine visit a popular pleasure-garden, the Promenade Grove, ten years after it had closed.

The 1935 first edition with its gorgeous cover and pugilist both visible

The 1935 first edition with its gorgeous cover and pugilist both visible 1959 Pan edition. Georgette did not like covers that gave her readers the wrong impression of her books.In later years Georgette’s publishers did not always “Get” her work!

1959 Pan edition. Georgette did not like covers that gave her readers the wrong impression of her books.In later years Georgette’s publishers did not always “Get” her work!“Easily my best”

Georgette was proud of Regency Buck, and of the work she had put into it. Her friend Carola Lenanton (nee Oman) had read it and given her high praise which meant a great deal to Georgette who had long admired Carola’s own novels.

‘Kindly note Purple Patch (Clarence’s proposal). Carola Lenanton paid me the biggest compliment I’ve ever had by asking me whether I’d found it in some unknown memoir, & “lifted” it for my book. She said (though I shouldn’t repeat it) that “not one word was false, or out of place.” I knew it was a High Light, but so few people know enough history to recognize it as such!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 10 October 1935

The “Purple Patch” was a glorious speech uttered by the Duke of Clarence to Judith Taverner, Regency Buck‘s rich and beautiful heroine. The Royal Duke is in debt and eager to find a suitable heiress to marry in order to solve his financial problems. Judith is a woman of birth and breeding, she has character and intelligence, but best of all she has money – lots of it! In this delightful paragraph, Heyer gives her readers so much more than a persuasive argument as to why Judith should accept the Duke’s proposal for here is history in a nutshell:

Oh you mean my brother, the Regent! I do not know why he should oppose it. He is not at all a bad fellow, I assure you, whatever you may have heard to the contrary. There’s Charlotte to succeed him, and my brother York before me. You may depend upon it he thinks the Succession safe enough without taking me into account. But you do not say anything! You are silent! Ah, I see what it is, you are thinking of Mrs Jordan! I should not have mentioned her, but there! you are a sensible girl; you don’t care for a little blunt speaking. That is quite at an end: you need have no qualms. If there has been unsteadiness in the past that is over and done with. You must know that when the King was in his senses we poor devils were in a hard case–not that I mean anything disrespectful to my father, you understand–but so it was. We have all suffered–Prinny, and Kent, and Suss, and poor Amelia! There’s no saying but that we might all of us have turned out as steady as you please if we might have married where we chose. But you will see that it will all be changed now. Here am I, for one, anxious to be settled, and comfortable. You need not consider Mrs Jordan

Georgette Heyer, Regency Buck, Pan, 1959, pp.167-168

A “gay adventure”

Georgette Heyer loathed this title for her first Regency novel which was changed without her permission.

Georgette Heyer loathed this title for her first Regency novel which was changed without her permission.‘She chose that filthy title, Gay Adventure, (it makes me sick to write) without one word to me!’

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, assistant to L.P. Moore, letter, 26 May 1935

In 1935, Georgette’s agent, L.P. Moore, sold the serial rights for Regency Buck to the prestigious women’s magazine, Woman’s Journal. It was a feather in any author’s cap to have a novel serialised in Woman’s Journal for it was widely read by both women and men and an excellent way to achieve greater exposure to the reading public. The magazine’s editor was the formidable and powerful, Dorothy Sutherland, and it was she who decided to change Heyer’s title from Regency Buck to “Gay adventure”. It was a mistake which incurred Georgette’s wrath and resentment – a resentment that was to last for thirty years. So great was her dismay at the new title and the awful subheading for her beloved novel, that from then on Georgette referred to Miss Sutherland as the “S.B.” or “Sutherland Bitch”. It rankled to have her elegant tale cast as something prurient in which “men were men and women were seductuvely coy”. Georgette did not write those kinds of books and would rail against any publisher who misled readers with the wrong kind of cover or advertising strap line. In the case of Regency Buck it was particularly annoying for the book’s heroine, Judith Taverner, was neither seductive nor coy.

An enduring classic

Written 85 years ago, Regency Buck has remained in print ever since. An enduring novel, it set the tone for the Regency novels to come, although Heyer never again created quite such a masterful hero as Lord Worth. In 1970, Germaine Greer offered a commentary on romance in her iconic book, The Female Eunuch. In it she described Lord Worth as “her masterful father-lover”, a character-type which Heyer used less and less as her Regency novels evolved. In many of her future novels, relationships between hero and heroine would become more and more relationships of equals and of friends. But she was hugely satisfied with Regency Buck and she had revelled in the language of the period, the costume, the people and the culture. It was Jane Austen’s era and Heyer’s ear was finely attuned to the language, inflection and syntax of her favourite author’s novels and it would shine through in her Regencies. As Heyer herself concluded:

I am inclined to think it is a classic! I don’t really know how I came to write anything so good. I do remember putting in a lot of work on it – And how I loved writing it! The characters in it say “Very true” & “Depend upon it” & Their spirits get “quite worn-down”, & it is “long before the evils of it ceased to be felt” And as for the Earl of Worth – ! Talk of “Heyer-heroes”! He tops the lot for Magnificence, Omnipotence, Omniscience, & General Objectionableness. However, he is more human than the ever popular Duke of Avon, because on one occasion (when Miss Taverner said she was glad he wasn’t her father) “he looked thunder-struck”. Yes, & now I come to think of it, he lost his temper with Miss Taverner & indulged in three pages of recriminations. Avon would have looked down his nose merely.

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, assistant to L.P. Moore, letter,16 May 1935

The 1981 Pan edition

The 1981 Pan edition The 2006 Arrow editionAs Georgette Heyer continued to be a bestseller long after her death in 1974 her covers became more elegant and better reflected the style of her novels

The 2006 Arrow editionAs Georgette Heyer continued to be a bestseller long after her death in 1974 her covers became more elegant and better reflected the style of her novels September 11, 2020

Death in the Stocks – “mirth and murder”

By 1934 the Rougiers were comfortably settled into their new home of Blackthorns at Toat Hill, near the market town of Horsham wwhere Ronald had his sports store. Blackthorns was a large, comfortable house and Georgette had a maid and possibly a cook-housekeeper to ease the domestic burden. She needed the support for she was writing at full speed again and as she once said frankly, “let me tell you (for my biography) that neither by training nor by temperament am I suited to Domesticity”. Her ability to focus on her writing would see Georgette produce twelve books in the seven years she lived at Blackthorns. She’d begun publishing two books a year in 1928 and, with only a few exceptions, would manage to continue this writing regime until 1943 which would be her first year withour a new novel since 1926. It was undoubtedly demanding, but Georgette loved to write and was brimming with ideas. It was in the 1930s that she began to write one detective story and one historical novel a year, alternating between the two styles, with a separate publisher for each. It is a rare author who can achieve a high degree of success writing in two different genres and find a large audience for each, but with talent and discipline Georgette Heyer did it and it is a testament to her skill that both her detective and her historical novels have remained in print ever since their first publication.

The original 1935 Longmans first edition dustjacket for Death in the Stocks

The original 1935 Longmans first edition dustjacket for Death in the Stocks“Miss Heyer shows her gift for creating character”

Many people consider Death in the Stocks to be Georgette Heyer’s best detective novel. It is certainly her wittiest and she obviously enjoyed writing it. It is a novel of firsts: her first book where her characters crack jokes over the corpse and do their best to put off the police by suggesting that they each might be the murderer; her first where she introduces Superintendent Hannayside, who would appear in her next few mystery novels; and the first of her detective novels written without her husband Ronald’s assistance. This last point is likely due to the fact that the murder victim is found dead on page two and the manner of his death is obvious – there was no ‘howdunit’ in Death in the Stocks for Ronald to devise or explain to Georgette (as he had to do with No Wind of Blame). The characters in the novel are fully realised and Dorothy L. Sayers said of them: ‘Miss Heyer’s characters and dialogue are an abiding delight to me…I have seldom met people to whom I took so violent a fancy from the word “Go”.’ These delightful characters are the charming yet infuriating Verekers and the intelligent solicitor, Giles Carrington. It seems likely that Georgette did not know she would use Hannayside again when she wrote Death in the Stocks, for it is Carrington and not the Superintendent who eventually solves the crime.

The delightful American first edition of

Death in the Stocks

The delightful American first edition of

Death in the Stocks

“Humour and mystery so perfectly blended”

Death in the Stocks was to be Georgette’s final book for Longmans. She had been growing increasingly dissatisfied with the firm and had not been entirely happy with their handling of her previous detective novel, the Unfinished Clue. Like many authors, Heyer always felt that her publisher could do a better job of promoting her books and by the time Death in the Stocks was due to be published she had become almost cynical about Kenneth Potter of Longman’s messages about her books. It was Kenneth Potter who, in 1932, had written to Georgette when Richard was born to say that ‘he hoped he & Footsteps were going to be my two most successful works’. Georgette had liked him well enough at the time to be pleased by his compliments, but by 1935 the gloss had worn off and his well-meaning message about her new novel evoked a cynical response from her:

‘You ought to see Potter’s latest effusions! He “feels sure he can sell Death in the Stocks”! Ha, Ha!’ had not been impressed by Kenneth Potter’s

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore

Potter’s efforts to keep Georgette with the firm were not successful. Longmans did not want to lose her and were disappointed by the decision for her reputation as a witty crime writer was growing and she was a reliable writer whose sales were increasing. On 19 February 1935 – just two months before Longmans were to publish Death in the Stocks – Georgette formally ended her relationship with the publisher and signed a new contract with Hodder & Stoughton for ‘her next four new and original “modern” novels’. Never comfortable with conflict or having to face trouble head on, after signing the new contract, Georgette confessed to her agent, L.P. Moore, ‘I dread the inevitable spate of reproachful letters from Potter’, and begged Moore to ‘head him off’. Despite her departure from the firm only weeks before they published Death in the Stocks Longmans did Heyer proud. and the novel received glowing reviews in several major British papers.

Although Miss Georgette Heyer’s publisher’s describe her latest book as “A thriller”, it is more considerable and certainly more satisfying than the type of novel that commonly goes by that name, for Death in the Stocks is not only a very neat and mystifying detective story, it is also an excellent example of what can be achieved when the commonplace material of detective fiction is worked up by an experienced novelist. Miss Heyer’s characters act and speak with ease and conviction that is as refreshing as it is rare in an ordianry mystery story.

Times Literary Supplement, 18 April 1935

The Sun Dial edition of

Death in the Stocks

which was also published in 1935.

The Sun Dial edition of

Death in the Stocks

which was also published in 1935.Merely Murder in America – “Mustn’t miss this”

Georgette had not had a novel published in America since Longmans had brought out Beauvallet in 1930. In 1935, however, Doubleday Doran brought out Death in the Stocks under the new title of Merely Murder as part of their Crime Club series with a teaser on the cover that read: with a quote on the cover which read: ‘A rare and refreshing novel of mirth and murder among the mad young Verekers’. Georgette was pleased to have an American publisher again and wrote from her sickbed to Moore’s assistant, Norah Perriam, to say “I feel quite elated, & have decided not to die after all.” Doubleday produced the first of several striking covers for her mysteries and the book sold so well that it marked the beginning of Doubleday’s publication of all Georgette’s crime novels in America.

The secret lies is Miss Heyer’s remarkable gift for portraiture in the round; she makes the wayward Vereker family about whom suspicion hovers not only alive but positively frisky.

Ralph Partridge, “Death Everywhere”, The New Statesman and Nation, 4 May 1935

On Broadway

In 1936 Georgette received word that an American playwright wanted to produce Death in the Stocks on Broadway. The writer was to be Mr A. E. Thomas, a New York playwright with more than two dozen produced scripts to his credit and whose most recent play No More Ladies had been made into a film the previous year with Joan Crawford and Robert Montgomery in the starring roles. The Playwright had been drawn to the idea of converting Heyer’s novel into a play by the quality of her dialogue, by the characters’ personalities and the question as to Kenneth Vereker’s guilt or innocence. Thomas was keen to have Georgette’s comments and suggestions for the script and sent first and second drafts of it to her in England. She read the second draft in November 1936 and instantly became concerned that Thomas had lost sight of his original intention and turned down the vaudeville path rather than trying to maintain the wit and humour of the original story. She told her agent that, ‘Wit & custard-pies don’t mix. If he tries to introduce “mad situations” he will fall between two stools’ and that ‘the more Mr Thomas deviates from my text the worse the play grows’. Georgette hoped to go to New York to work with Mr Thomas in person but it proved impossible and in the end he finished the script and the play went on. It ran for three nights and then closed. Although A.E. Thomas never had a Broadway hit (none of his plays ran for longer than six months) he was accounted a successful playwright and many of his scripts were adapted for Hollywood and made into films. Death in the Stocks, on the other hand, continues to sell around the world.

The 1942 Penguin edition which was reprinted in 1944

The 1942 Penguin edition which was reprinted in 1944 The 1935 pocket-sized Tauchnitz edition

The 1935 pocket-sized Tauchnitz edition The 1962 Dutton edition published in America

The 1962 Dutton edition published in America

August 28, 2020

The Unfinished Clue – “pure joy from start to finish”

The 1934 Longmans’ first edition of

The Unfinished Clue

The 1934 Longmans’ first edition of

The Unfinished Clue

By August 1933 Georgette And Ronald had moved into their new home, Blackthorns, in Toat Hill near Slinfold, Sussex. The house was a large and comfortable one and the Rougiers had at least two servants to help with the domestic work and a nurse for Richard. He was a bright, exuberant child and his parents were proud of him, although in the typical English style of the time, they were not tactile parents and did not encourage overt displays of emotion. Georgette’s main outlet for her emotions was always her books and Blackthorns proved to be ideal for writing. It was very private and it had a large garden and woods in which to walk. Georgette always enjoyed gardens and often found respite in them from her busy writing life.

Georgette picking sweet peas in the garden at Blackthorns.

Georgette picking sweet peas in the garden at Blackthorns. Ronald relaxing on the front porch at Blackthorns.

Ronald relaxing on the front porch at Blackthorns.Georgette began writing her third detective novel soon after the move to Blackthorns. Originally called Murder on Monday, Longmans would publish the book in March 1934 as The Unfinished Clue. As with her previous detective-thriller, Why Shoot a Butler? the setting was an English country house and once again Georgette introduced a one-off detective. Inspector Harding is a charming policeman and a gentleman and, if she had not chosen to marry him off to the novel’s very intelligent heroine, Dinah, by the end of the novel, Georgette might well have made of him one the genre’s iconic detectives. Harding is an engaging young man who deals admirably with the novel’s difficult characters. These are many, beginning with the unpleasant and belligerent Sir Arthur Billington-Smith, his weak-willed, nervous wife, Faye, her strong-silent-type lover, Stephen Guest, Sir Arthur’s angry and rebellious son, Geoffrey, and, best of all, Geoffrey’s marvellous fiancée, Lola de Silva, a Mexican cabaret dancer who is utterly oblivious to the protcols and etiquette of an English country-house party! It is Lola who sets the house by the ears and Lola who inspired the great Dorothy L. Sayers to write of The Unfinished Clue:

‘I said last week that good writing would often carry a poor plot, and here is a case in point. Reduced to its main outlines The Unfinished Clue has the stamp of stereotype all over it. Here is the same old week-end party: the disagreeable rich man, who is stabbed in the study, the down-trodden wife, the rebellious son with the undesirable fiancée, the hard-up nephew, the wife’s lover, the husband’s petting-partner and her husband — all the stock characters, including the mysterious widow out of the victim’s past and the gentlemanly detective with the sugary love affair, together with a solution which had grown whiskers in the sixties [1860s!] and is as preposterous now as it was then. And yet, simply because it is written in a perfectly delightful light comedy vein, the book is pure joy from start to finish. Lola, the fiancée, by herself is worth the money, and, indeed, all the characters from the Chief Constable to the Head Parlourmaid, are people we know intimately and appreciatively, from the first words they utter. Miss Heyer has given us a sparkling conversation-piece, rich in chuckles, and all we ask of the plot is that it should keep us going until the comedy is played out.

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Sunday Times, 1 April 1934

The 1942 Longmans’ “A Murder Mystery by Georgette Heyer Series” edition of

The Unfinished Clue

The 1942 Longmans’ “A Murder Mystery by Georgette Heyer Series” edition of

The Unfinished Clue

The Unfinished Clue received several good reviews, but it would not appear in America until 1937, three years after its UK publication. By then Doubleday Doran had already published three of Georgette’s detective novels, changing the name of Death in the Stocks to Merely Murder for the benefit of those Americans unfamiliar with the sight of stocks on the village green and which would feature so prominently in that particular novel. An astute publisher, Doubleday designed a series of excellent dustjackets for half a dozen of Heyer’s mystery novels, including the “cast of characters” jacket for The Unfinished Clue in which four of the main characters each have their own logline to hook the reader. Her novel’s delayed sale to Doubleday and belated appearance in the USA may have been one of the reasons for Georgette’s growing dissatisfaction with Longmans’ handling of her books. In 1930, Georgette had been appalled by the publisher’s jacket design for her final contemporary novel, Barren Corn, and unimpressed by the firm’s head, Willie Longman, whom she once described as ‘vapid’. In March 1934, shortly after the publication of The Unfinished Clue, Georgette met her agent, Leonard Moore, at her club to discuss her future with Longmans.

The American1937 Doubleday Doran “Crime Club INC.” edition of

The Unfinished Clue

with its fabulous dustjacket.

The American1937 Doubleday Doran “Crime Club INC.” edition of

The Unfinished Clue

with its fabulous dustjacket.Here’s an elegant buy in smart, streamlined bafflement by the author of Merely Murder [Death in the Stocks], Why Shoot a Butler?, and Behold, Here’s Poison. Clever gabble, malicious characterization. fool-proof plot and high excitement are among the treats.

Will Cuppy, describing The Unfinished Clue in his article “Mystery and Adventure”, New York Herald Tribune Books, 21 February 1937

Although she was not really a ‘club’ sort of person, early in the 1930s Georgette had joined the Empress Club in Dover Street in central London. Established in 1897 as a club for women, its subscribers were a mix of upper-class, educated and professional females. Purpose-built and well-designed, the club

‘boasted two drawing rooms, a dining room, a lounge, a smoking gallery and a smoking room, a library, a writing room, a tape machine for news, a telephone, a room in which servants could be interviewed, dressing rooms, and one of the best orchestras in London.’

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928, Routledge, New York, 2001, p.120.

The Empress Club was an elegant and sophisticated environment which entirely suited Georgette and enabled her to play host to her agent or friends at lunch when she visited the capital. She and Moore met there late in March 1934 to discuss her books. Georgette had begun a new book about which she was very enthusiastic, but she also wanted to complain to him about Longmans. She was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the firm’s handling of her detective novels and had been less than impressed when, after sending back the page proofs of The Unfinished Clue , she had received ‘frantic and numerous telephone messages desiring me to inform them where are the proofs?’ This sort of inefficiency was something she loathed and enough to make her think of leaving the firm. Over the years and as evidenced in her many letters, once Georgette’s displeasure or disapproval was incurred it generally marked the beginning of the end. She was very protective of her books and of her creative life and could be very stubborn where they were concerned. It usually took her a long time to change direction or make a decision to change a long-standing arrangement, but once she had made up her mind the decision was nearly always irrevocable.

The 1945 Penguin (no. 428) wartime edtion of

The Unfinished Clue

The 1945 Penguin (no. 428) wartime edtion of

The Unfinished Clue

It was an easy commute from Blackthorns to London as, in the 1930s, Horsham had its own station on the Guildford branch of the Southern railways. Georgette visited London to shop, lunch at her club or meet her agent who, before the Second World War, had an office in the city. She had a busy life and her writing took up a great deal of her time. During her research for the Private World of Georgette Heyer, Jane Aiken Hodge spoke to locals who remembered Georgette, in particular:

‘The old lady who lived at the end of the drive remembers Richard as a lonely little boy who would come and see her and tell her that Mummy was busy writing. His father would drop in and pick him up on his way home from work. His grandmother, Mrs Heyer, had moved to Horsham and she, too, was apt to complain that her daughter was always busy.

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, p.45

It must have been hard for Georgette being the main family breadwinner, attending to Richard and to her mother whenever she could, keeping the house running smoothly, and writing two books a year as she would throughout the 1930s (she published only one book in 1931 and 1939). Georgette’s creative powers were remarkable but she did pay a price for her productivity, an experience with which many male writers of her era were far less familiar. In these modern times, it is easy to be critical of her apparent neglect of Richard but for a woman of her class it was not so unusual to have one’s child attended to by a nurse or a nanny. Georgette loved Richard and he always knew that although there were times when he longed for a closer emotional tie with his mother. The Unfinished Clue was the next step in Georgette’s evolution into a writer with a growing reputation for writing detective stories that were not only clever, but also witty. She had a penchant for writing characters with a propensity for making jokes about the corpse and doing their best to infuriate the police. This would bear fine fruit in her very next book, Death in the Stocks.

The American 1970 Dutton dustjacket of

The Unfinished Clue

The American 1970 Dutton dustjacket of

The Unfinished Clue

August 21, 2020

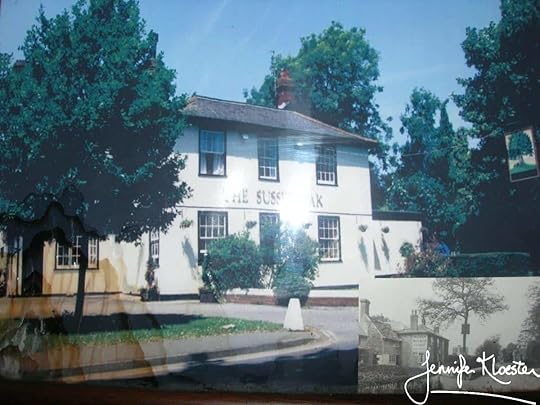

The Convenient Marriage – written at the Sussex Oak

The Sussex Oak in Warnham where Georgette Heyer began writing

The Convenient Marriage

.

The Sussex Oak in Warnham where Georgette Heyer began writing

The Convenient Marriage

.By May 1933, Georgette and Ronald, with baby Richard, had left Southover, their rented house in Colgate, and moved into the Sussex Oak in Warnham, a couple of miles from Horsham. The seventeenth-century inn was to be their home for some weeks while they looked about the neighbourhood for a long-term rental. Richard was now 15 months old and an engaging child. The lease on Southover had expired and his parents wanted somewhere more permanent to raise him. From his infancy, Georgette had employed a nurse or a nanny to help care for Richard, an approach to child-rearing that was very much in the British tradition, but one that was also necessary if she were to continue writing. In 1933, she published only one book, Why Shoot a Butler?, and this was no doubt due to her having given birth the previous year. Though Ronald was still running the sports store in Horsham, his income was not enough to cover their expenses and Georgette knew that she needed to write two books a year until she had established a large enough royalty stream to support their lifestye. In 1934, the first of those two books would be The Convenient Marriage.

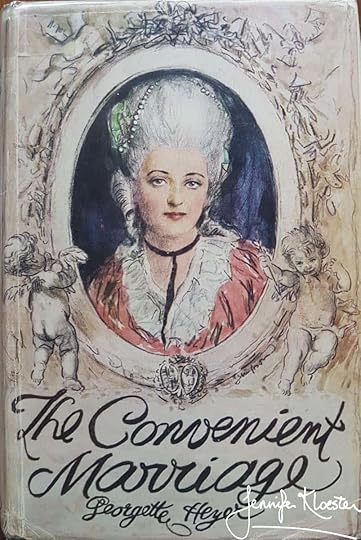

The 1934 Heinemann first edition dustjacket for Georgette Heyer’s sixth 18th-century novel.

The 1934 Heinemann first edition dustjacket for Georgette Heyer’s sixth 18th-century novel.“I’m thinking of calling it The Convenient Marriage. O.K.?”

The new novel was to be her sixteenth book and her sixth story set in the eighteenth century, with all the colour and glamour intrinsic to the period with its fabulous clothing, face patches, jewel-encrusted shoes and extravagant headwear. The hero (surprisingly) is ‘an exquisite’ whose (unsurprisingly) ‘laced and scented coats concealed an extremely powerful frame’ and who, on the surface at least, cares far more for the cut of his top-boots, the choice of his coat (dos de puce or blue velvet?) and the style of his wig (the perruque à bourse or the Catogan?) than for the matters of state in which his earnest young secretary, Arnold Gisborne, wishes he would take an interest. Heyer is so clearly at home in the era and, despite the fact that she was living in a country inn when she wrote the first third of The Convenient Marriage and did not have her library about her, she easily created a sense of period in this gently humorous historical novel. Heyer always read widely and the literary influences in her novels are many with a decided predilection for the works of Shakespeare and Jane Austen. Indeed, the scene where the youthful and impetuous newly-married Countess of Rule visits her family after her honeymoon is reminiscent of the newly-married Lydia Bennet’s return to Longbourn in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

At first glance she seemed to her sisters to have changed out of all recognition. Evidently the day of demure muslins and chip hats was done, for the vision in the chaise wore a gown of tobine striped over a large hoop, and the hat perched on top of curls dressed à la capricieuse bore several waving plumes.

Georgette Heyer, The Convenient Marriage, Pan, 1966, p.56.

A “stylish romantic comedy”

The Convenient Marriage is the first of Georgette Heyer’s novels in which the hero and heroine are married early in the story. Marcus Drelincourt, Earl of Rule, is 35, bored and handsome. Horatia (Horry) Winwood, aged 17, is the youngest of three sisters, one at least of whom must marry money. It is the eldest, the beautiful Miss Elizabeth WInwood, who has reluctantly agreed to sacrifice the man she loves, Edward Heron – a mere lieutanant and an impecunious younger son – and marry Rule in order to save the family fortunes. But it is the youngest, Horry, who risks scandal by visiting the Earl at his home and offering herself in marriage in place of her sister. With consummate skill Georgette Heyer sets up this fantastic story in the first twenty pages and carries it off with such style that the story quickly evolves into one of her delicious confections of wit and intrigue. As Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, said The Convenient Marriage ‘glows with the with the kind of stylish romantic comedy that was to be her hall-mark’.

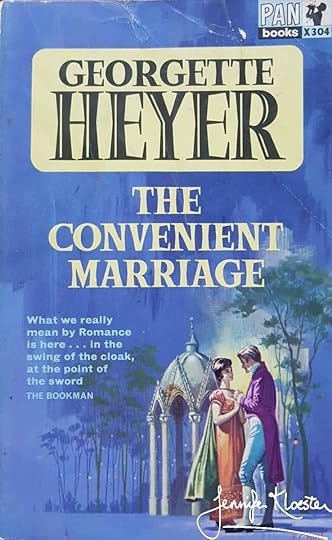

From its first publication in 1934

The Convenient Marriage

has had multiple printings and remains a favourite with Heyer readers.

From its first publication in 1934

The Convenient Marriage

has had multiple printings and remains a favourite with Heyer readers.Written with pen and ink

In the first two decades of her long career, Georgette Heyer often wrote at night, frequently staying awake until dawn writing with a fountain pen on the pages that would become her next novel. In the modern world where computers allow writers to edit, delete, cut and paste, etc. at the touch of a button and to create multiple drafts of their stories, it is hard to imagine writing with pen and ink which must have made rewriting so laborious. It is possible – perhaps even likely – that the pen-and-ink process itself helped to ensure that for many authors early drafts were often close to or actually final drafts. This does seem to have been true for Georgette Heyer whose ability to write quickly and to pen first drafts that were often final drafts was extraordinary.

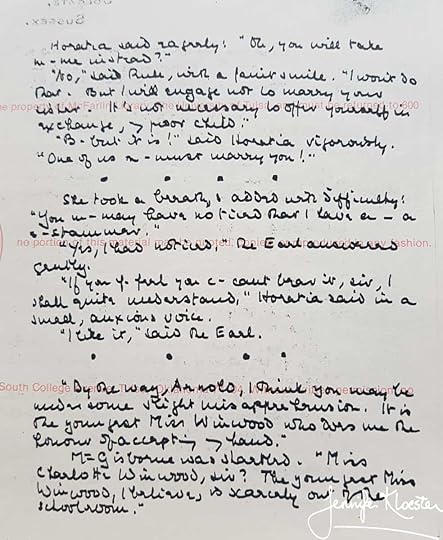

“I’m glad you like my excerpts”

Staying at the Sussex Oak must have had its challenges, but it does not seem to have affected Georgette’s creativity. It is not known if she wrote The Convenient Marriage in her bedroom or at a table in one of the public rooms of the old inn, but wherever she wrote it, the words came easily and in such flowing style that she was prompted to write out several excerpts and send them to her agent, L.P. Moore, for his entertainment. A perusal of these excerpts show them to be identical to what eventually appeared in the published book – something many authors would envy and editors would find incredible!

A few of the excerpts from

The Convenient Marriage

which Georgette Heyer wrote out for her agent’s entertainment.

A few of the excerpts from

The Convenient Marriage

which Georgette Heyer wrote out for her agent’s entertainment.‘this highly scintillating letter”

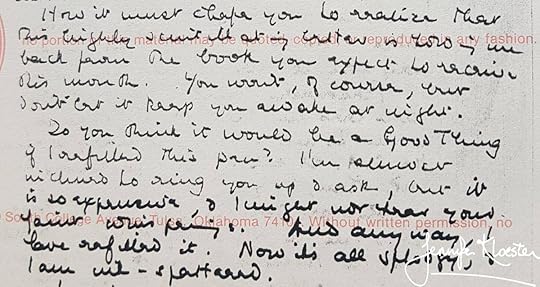

Georgette’s idiosyncratic handwriting where the ‘e’s look like ‘a’s and the running script is sometimes difficult to decipher, but it is so much more interesting than a typed letter or an email. In letters to friends or close associates she often used a stream-of-consciousness style as she does here when telling her agent how writing the letter ‘is holding me back from the book you expect to receive this month’ and asking him if she should refill her pen. Then the ink changes from light to dark and we are in the moment when Georgette has stopped writing, refilled her pen, and returned to her letter to tell him she has done so. How vividly one can imagine her doing that!

‘How it must chafe you to realize that this highly scintillating letter is holding me back from the book you expect to receive this month. You won’t, of course, but I shouldn’t let it keep you awake at night. Do you think it would be a Good Thing if I refilled this pen? I’m almost inclined to ring you up & ask, but it is so expensive, & I might not hear your faint whisperings [Moore had lost his voice]. And anyway, I have refilled it. Now it’s all splodgy, & I am ink-spattered.’

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, written at the Sussex Oak, Warnham, 27 May 1933.

The dramatis personae for The Convenient Marriage

As well as writing out ‘choice excerpts’ for Moore, two weeks earlier Georgette had also written out her dramatis personae for his edification. This was usually how she began her books: she would think up several characters, give them names (her characters’ names were always vitally important to her) and come to know their personalities and characteristics and then drop them into a scene. From there, her characters would then act according to their various natures and the story would evolve, with each character following their natural story-arc until the book’s inevitable and satisfactory end. Heyer’s characters lived for her and she would talk about them to her agent as if they were real people: ‘isn’t it sad about Caroline Massey? Not a Nice Woman at all’.

‘Would you like to hear my Dramatis Personae? No? Well, it’s too late now, you’ve got to.

Marcus Drelincourt, Earl of Rule. Hero of the best type. Very pansy, but full of guts under a lazy exterior. Aged 35.

Elizabeth Winwood, lady in the best XVIIIth cent. tradition. Sweet & willowy. Age 20

Charlotte Winwood. Improving spinster. 19

Horatia Winwood. A stammering heroine, of the naïve & incorrigible variety. 17

Pelham, Viscount Winwood. Brother to above ladies. Young rake & spendthrift. Provides light relief.

Maria, Viscountess Winwood. Mother to all the above Winwoods. An invalid of exquisite sensibility.

Edward Heron. Lieutenant of the 10th Foot, invalided home from Bunker’s Hill. Enamoured of Elizabeth.

Louisa, Lady Quain. Trenchant sister to Rule.

Sir Humphrey Quain. Her husband.

Arnold Gisborne. Secretary to the Earl of Rule.

Caroline, Lady Massey. I regret to say, Rule’s discarded mistress.

Crosby Drelincourt. Cousin & heir-presumptive to the Earl of Rule. A Macaroni, & a nasty piece of work, taken all round.

Robert, Baron Lethbridge. Best type of villain. Fierce & hot-eyed & sardonic.’

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, written at the Sussex Oak, 10 May 1933.

“Yes, but I’ve Stuck”

In writing most of her novels, Heyer would eventually get ‘stuck’, coming to a place where she had no idea what her characters were going to do next. This happened with The Convenient Marriage and, on telling Ronald about it, he merely said, ‘”Ah! I’ve been waiting for that”‘ before enumerating to her ‘all the Sticking places in all the books I’ve written ever since I married him’ . Ronald also confidently told Georgette that she would very likely ‘surmount this obstacle’ just as she had always done. Where she had become stuck was in chapter three where the hero, Lord Rule, goes to visit his mistress, Lady Massey. Georgette described the problem to Moore with her tongue firmly in her cheek:

‘Yes, but I’ve stuck. Here I am, in Lady Massey’s boudoir (all rose pink and silver, you know), & I can’t either talk to her, or get away. The trouble is I’ve led such a sheltered life. It’s a frightful drawback, & I do think young females about to embrace a literary career ought to get to know a few good demi-mondaines. Personally, I can’t make out what Rule sees in that odious Massey. She seems to me a very ordinary woman. No S.A. [sex appeal] at all. But you never know with Men, do you?’

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, written at the Sussex Oak, 27 May 1933

Blackthorns, Toat Hill, near Slinfold, Sussex. Georgette Heyer wrote the rest of

The Convenient Marriage

here and another dozen books.

Blackthorns, Toat Hill, near Slinfold, Sussex. Georgette Heyer wrote the rest of

The Convenient Marriage

here and another dozen books.The move to Blackthorns

Georgette and Ronald eventually found the perfect home to rent. This was Blackthorns, a large, red-brick house, set at the end of a long driveway in 15 acres of garden, a wood in which nightingales sang, a stream, a pond and a well. Large trees meant you could not see the house from the road making it very private, which exactly suited Georgette. It was also close enough to Horsham, some four miles away, to be convenient for shopping, the cinema and for Ronald’s work. Georgette finished writing The Convenient Marriage at Blackthorns and over the next six years she would write another dozen novels there. Richard spent his formative years at Blackthorns, before being sent to boarding school at the age of nine. His parents loved him but he was often lonely as his mother was busy writing. She adored him, however, and would often mention him in her letters to Moore or other friends. When he was 15 months old Georgette wrote humorously of Richard’s apparent attitude to The Convenient Marriage:

Richard ‘doesn’t care for the book. He does like a Womanly Woman, & thinks that a Mother’s Place is in the Nursery.’

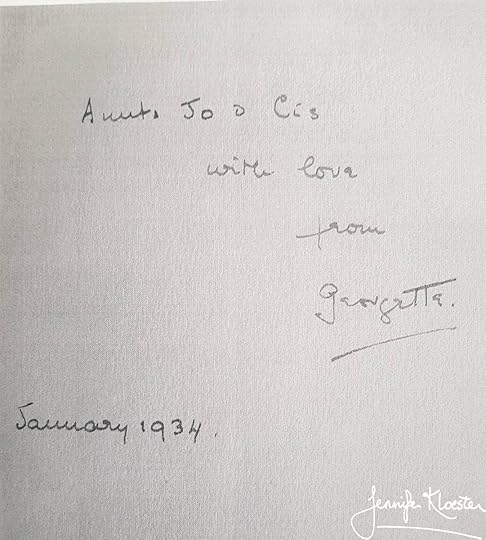

“Georgette Heyer is a Better Writer than You Think”

Heinemann published The Convenient Marriage in February 1934. From the first it sold well and has since had many reprintings. Georgette inscribed one of her advance copies to her beloved great-aunts, Cissy and Jo. Forty-five yearsafter its publication, in 1969, the author, A.S. Byatt, wrote the first serious appraisal of Georgette Heyer. It appeared in Nova magazine under the heading “Georgette Heyer is a Better Writer than You Think” and in it she offered her reasons for Heyer’s success:

‘I think the clue to her success is somewhere here–in the precise balance she achieves between romance and reality, fantastic plot and real detail. Her good taste, her knowledge and the literary and social conventions of the time she is writing about all contribute to a romanticised anti-romanticism: an impossible world of prettiness, silliness and ultimate good sense where men and women really talk to each other, know what is going on between them and plan to spend the rest of their lives together developing the relationship. In her novels, as in Jane Austen’s, it is love people are looking for, and love they give each other…

A.S. Byatt, “Georgette Heyer is a Better Novelist than You Think”, Nova, August 1969.

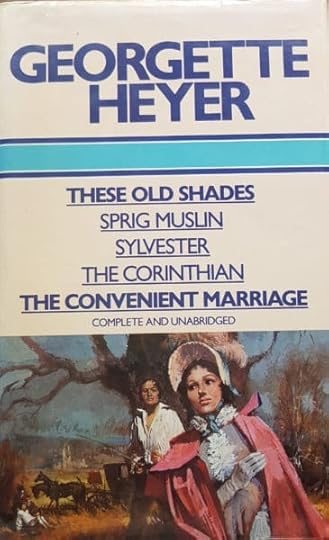

Just a few of the reasons to read Georgette Heyer!

The 1977 Omnibus and the 2006 Arrow edition of

The Convenient Marriage

The 1977 Omnibus and the 2006 Arrow edition of

The Convenient Marriage

August 15, 2020

Celebrating Georgette Heyer’s Birthday

Today, 16 August 2020, marks 118 years since Georgette Heyer was born at 103 Woodside, WImbledon. Five years ago, on 5 June 2015, I was privileged to speak at the unveiling of the English Heritage Blue Plaque awarded to Georgette for her contribution to literature. Stephen Fry, that brilliant actor, author and comedian, performed the unveiling and spoke about his love of this great author and of the lasting impression she made on him from first reading her novels at school. Georgette Heyer’s daughter-in-law, Susanna, Lady Rougier, also spoke affectionately of her mama-in-law, noting how pleased Georgette would have been to know that she had been awarded a Blue Plaque (though she would never have admitted it!). Major-General Jeremy Rougier (retired) also spoke of his fond memories of his aunt by marriage, of her kindness and her forceful personality. We were very fortunate to have a professional cameraman on scene that day and I thought you might enjoy celebrating Georgette Heyer’s birthday with those of us lucky enough to speak at this very special ceremony. I do hope you enjoy these videos.

August 14, 2020

Why Shoot a Butler? – “A classic tale of crime and detection”

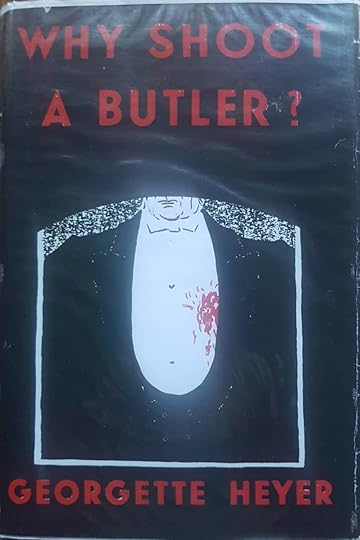

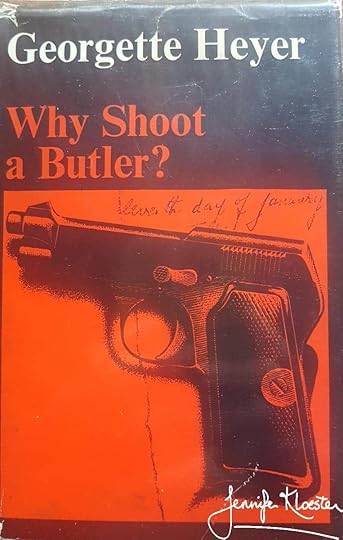

The 1933 first edition dustjacket of Georgette Heyer’s second detective-thriller.

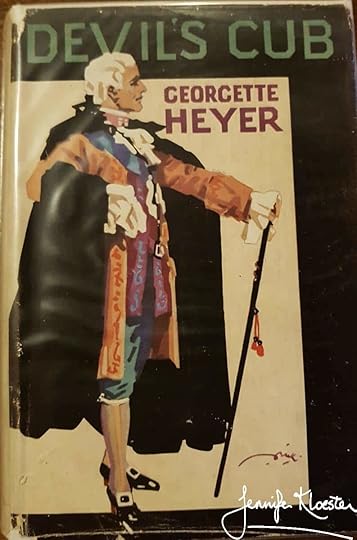

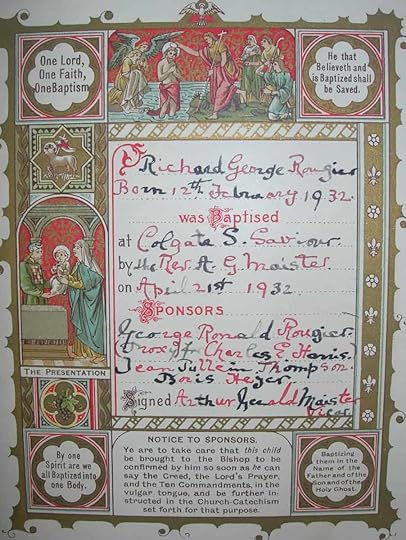

The 1933 first edition dustjacket of Georgette Heyer’s second detective-thriller.1932 – a landmark year

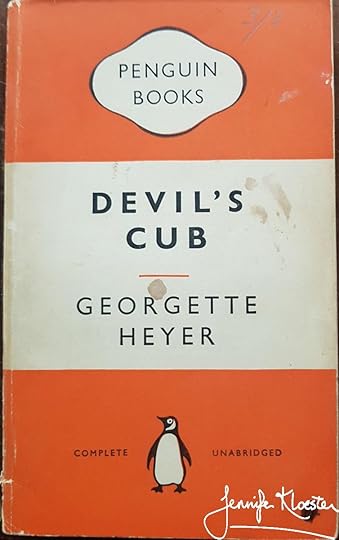

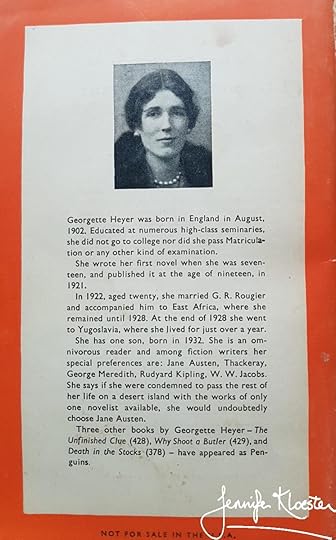

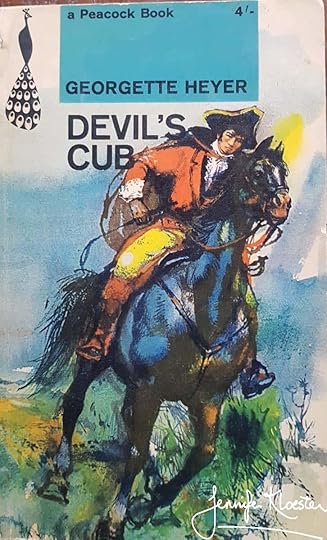

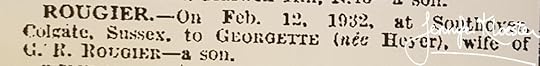

!932 proved to be a landmark year for Georgette Heyer. On February 12th she gave birth to her first (and only) child, a son, Richard, and on the very same day, Longmans published her first detective-thriller, Footsteps in the Dark. Thrilled to be a mother, but determined to go on writing, within months of Richard’s arrival Georgette had finished writing Devil’s Cub, the sequel to her bestselling novel, These Old Shades, and begun writing her second mystery novel, Originally called Half a Loaf – an obscure reference to the missing will upon which, in true classic detective style, the plot depends – Georgette wrote the novel with her accustomed speed and a great deal of verve. Her husband, Ronald, assisted with some of the more technical details to do with guns and cars and she eventually changed the title to Why Shoot a Butler? dedicating the book to Ronald with the enigmatic line ‘To One Who Knows Why’.

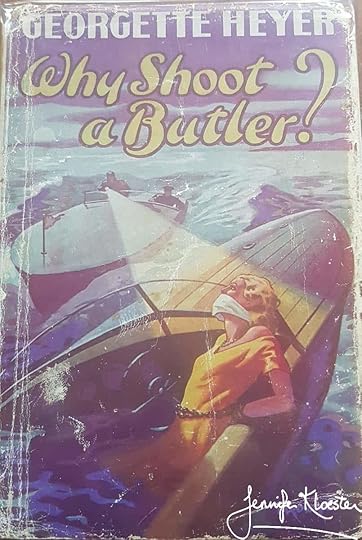

The dramatic 1937 dustjacket published by Longmans for their Georgette Heyer “The Detective Novels” series.

The dramatic 1937 dustjacket published by Longmans for their Georgette Heyer “The Detective Novels” series.I have always enjoyed Why Shoot a Butler? which is one of those ‘curl-up-by-the-fire-on-a-wintry-day’ type of novels. Even more than Footsteps in the Dark Why Shoot a Butler? is a character-driven story with lots of witty dialogue and a hero-detective in Frank Amberley who is described early on as ‘the rudest man in London, an attribute or foible which, as one commentator noted, gave Heyer

‘an opportunity for wit, which is consistently entertaining, and even, in a couple of the books, carefuly worked into the plot…the conceit of Frank Amberley, who honestly considers himself far cleverer than the police or anyone else and is charming in spite of it in Why Shoot a Butler?‘

Nancy Wingate, “Georgette Heyer: A Reappraisal”,.

Amberley is one of Heyer’s clever men of means, a lawyer and, though arrogant, remains attractive and debonair. We like him from the first meeting when he is driving down a lonely road in his ‘powerful Bentley’ and comes across the lone figure of a young woman standing by a ‘closed Austin Seven’. This first encounter between hero and heroine is caustic, sardonic and compelling and becomes even more so when Amberley discovers a body in the abandoned car and a gun in the lady’s pocket – all by page five! There are hints here of novels and characters to come, but Why Shoot a Butler? is very much a stand-alone book in the Heyer canon. It was also her only publication in 1933, no doubt due to the birth of her son, the publication of two novels, the writing of a third and the move to a new home.

Secluded Southover