Jennifer Kloester's Blog, page 9

June 5, 2020

These Old Shades – Always a Favourite (Part 1)

The 1926 first edition jacket for

These Old Shades

with a design by the artist Sydney Hulme-Beaman.

The 1926 first edition jacket for

These Old Shades

with a design by the artist Sydney Hulme-Beaman.Already written

It was fortunate for Georgette Heyer that what would become her sixth published novel was mostly written when, on 16 June 1925, her father died from a massive heart attack. Only the day before she had signed her first contract with Heinemann for Simon the Coldheart – already published in the USA – and for a second, unnamed book. Struggling with the devastating loss of her adored father, friend and mentor, but determined to fulfill her contract, Georgette tried to write. Five months later In November she told her agent: ‘I haven’t yet started another book but I’m trying to. I think it will be modern.’ But, despite her good intentions, the ‘modern’ novel would not appear for another two-and-a-half years.

A ‘sequel’

It may have been desperation that caused Heyer to return to the manuscript she had begun three years previously in 1922. In January 1923 the book was almost finished and she had written gleefully to her agent, L.P. Moore, to tell him about this planned ‘sequel’ to her first novel, The Black Moth.

Dear Mr Moore

Here is the Black Moth – a very juvenile effort. I do hope you’ll like it! At the risk of earning a dubious headshake from you, I will tell you that sometime ago I began a sequel to it, which one day I shall wish to publish … It isn’t finished yet, but it will be one day. I’d like to make a success, then to get the Moth out of Constable’s hands and to induce another publisher to reprint in a cheaper edition, and lastly to bring out the sequel!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 23 January 1923, University of Tulsa Archive

‘Designed to catch the public’s taste’

It was a very clear plan and required only that Georgette ‘make a success’ before putting the finishing touches to her unnamed manuscript. She knew exactly what the story was about and was confident that she understood what readers wanted and how to please them. With rare youthful candour and an exuberance that would diminish after her father’s death, she told Moore:

‘The sequel is naturally a much better book than the Moth itself, and is designed to catch the public’s taste. I have also tried to arrange it so that anyone who reads it need not first read the Moth. It deals with my priceless villain, and ends awfully happily. Tracy becomes quite a decent person, and marries a girl about half his age! I’ve packed it full of incident and adventure, and have made my heroine masquerade as a boy for the first few chapters. This, I find, always attracts people!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 23 January 1923, University of Tulsa Archive

Masquerade!

Georgette was familiar with many books and plays in which young women disguise themselves in male attire and thereby throw off the restraints and restrictions of their gender. Several of the Shakespearean plays – which Georgette knew and loved – featured heroines masquerading as men and the character of Britomart in Spenser’s Faerie Queen dons armour and has adventures in her male disguise. Georgette was also familiar with modern writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Berta Ruck, and Ethel M. Dell who also used the masquerade device.

Fair Rosalind (1888) by Robert Walker Macbeth (1848-1910)

Fair Rosalind (1888) by Robert Walker Macbeth (1848-1910) Portia by Henry Woods (English, 1846-1921])

Portia by Henry Woods (English, 1846-1921]) Shakespeare Illustrated Public DomainFrom her adolescence Georgette understood the appeal of masquerade and cross-dressing characters.

Struggling to write

But, despite her early enthusiasm, her father’s death stopped Heyer in her writing tracks and by November 1925 she had written nothing new. That month she told her agent, ‘I don’t think I have the heart to write a period novel.’ But Georgette had a contract to fulfill and, throughout her life, only serious illness would prevent her from meeting her contractual obligations. With no new book to offer Heinemann, she retrieved her unfinished manuscript and set about preparing it for publication.

Georgette’s adored father, George Heyer, on the day of his death. (used with permission)

Georgette’s adored father, George Heyer, on the day of his death. (used with permission)‘I will try once more…’

Georgette returned to the unfinished sequel to The Black Moth and slowly began writing again. She later described the experience of returning to an unfinished manuscript in her most autobiographical novel, Helen. At the very end of the book, her heroine, the eponymous Helen, returns to her unfinished novel months after her father, Jim Marchant’s, sudden death. For those who know Heyer’s own story, these paragraphs from Helen are a poignant reminder of what she had lost and her struggle to return to the writing she loved:

‘She unearthed the manuscript from the bottom of her trunk, and sat down to read it. It was very hard to do this; Marchant’s pencilled corrections occurred again and again; and again: more acutely than ever did she feel the need of him; she had to force herself to continue.’ But at the end she said:– “I must re-write a lot of this. I know more than I did when I wrote it. I think quite differently.” …

She had set herself this difficult task; she persevered with it, and conquered at last her shrinking, her spells of hopeless depression, and the unreadiness of a pen so long laid by. At first there seemed to be no purpose in the writing fof this book, since Marchant would never read it; a score of times she was on the point of relinquishing the attempt to write, but each time she thought:– “I will try once more,”‘ until gradually the old facility came back, and a little of the old joy of writing. It was a different pleasure she had in it now, lacking the exuberance she had felt before, but she was relieved to find that there was still pleasure in her work.’

The book was finished at last, and sent to the typist. The spring came back into Helen’s step, and the light into her eyes. “There are still things to do,” she said.

Helen, Georgette Heyer, Longmans, 1925, p.325.

The memorial stone to George Heyer at King’s College Hospital where he had been the Appeals Secretary.

The memorial stone to George Heyer at King’s College Hospital where he had been the Appeals Secretary.Like Helen in her novel, Georgette completed her manuscript and sent it to Heinemann. They published These Old Shades on 21 October 1926 with a first printing of 4500 copies. From the very first These Old Shades sold well, with a second printing of 4500 in March 1927 and another 4500 just eight weeks later in May. In its first ten years, These Old Shades would be reprinted almost thirty times. It was a phenomenal result for its twenty-five year-old author.

May 29, 2020

Who loves Simon the Coldheart?

A hero with attitude!

I love Simon the Coldheart because from the moment he walks (literally) onto the page you’re hooked. Simon is one of Georgette Heyer’s truly compelling characters. At the beginning of the book he is only fourteen and yet he has a presence and a way of speaking that draws you in and keeps you reading. I just love his attitude!

‘I have never approached my goal through the back door, my lord, nor ever will. I march straight.’

Simon the Coldheart, Georgette Heyer, Pan, 1979, p.17

Shakespeare’s influence

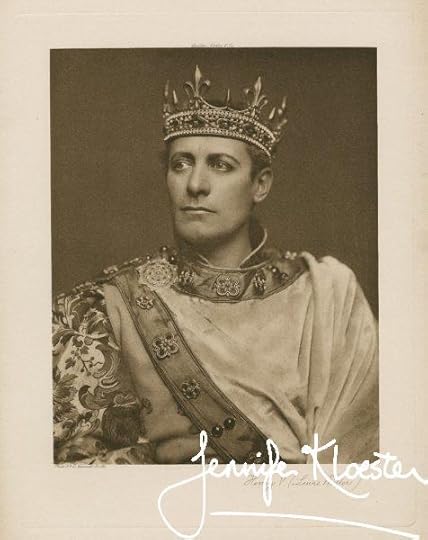

Simon the Coldheart is not an eighteenth-century Heyer novel, but a medieval story set in the reigns of King Henry IV and Henry V. Georgette had grown up reading Shakespeare and the Bard’s words and stories were deeply familiar to her. Throughout her writing career she would often reference Shakespeare in her books’ titles as well as in her characters’ interactions, personalities and speech. It may have been Shakespeare’s ‘Henry’ plays that inspired her love of the medieval era. Certainly her fascination for the period and for characters such as Hotspur in Henry IV and good King Harry in Henry V shows in Simon the Coldheart. Throughout her life Georgette would pursue her deep interest in the medieval era and Simon the Coldheart would be the first of three imedieval novels – each of them important in her writing career.

A photograph of Lewis Waller as Henry V, from a 1900 performance of the play

A photograph of Lewis Waller as Henry V, from a 1900 performance of the playLizzie Caswall Smith – Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/625d3g

Simon’s choice

Simon is the illegitimate son of one Geoffrey of Malvallet and a peasant woman, Jehanne. Simon’s mother is dead and he feels no allegiance to his father but seeks instead a place at the court of the Earl of Montlice also known as ‘Fulk the Lion’. Fulk is Geoffrey of Malvallet’s greatest enemy, which is another reason why young SImon has chosen Fulk:

‘Men call you the Lion, my lord, and think it harder to enter your service than that of Malvallet.’

‘Ye like the harder task, babe?’

Simon considered.

‘It is more worth the doing, my lord,’ he replied.’

Simon the Coldheart, Pan, 1979, p.19

Simon has also named himself ‘Beauvallet’, a clever wordplay on his birth father’s name, changing the French word for evil – ‘mal’ – into the French word for fair or fine – ‘beau’. The name tells us much of Simon’s character and his determination to make his mark in the world. Simon grows up and becomes a knight, fighting for Henry IV at the Battle of Shrewsbury and later for Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt. It’s a great blend of story and history and it’s often sent me to history books and websites to find out more about the people and places in the story. I love Heyer’s light touch and her brilliance in depicting fictional characters taking part in historic events. Simon the Coldheart is the first of her novels in which she achieves this compelling blend of history and fiction.

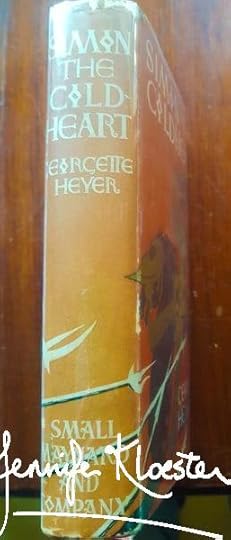

America first

Simon the Coldheart was Georgette Heyer’s fifth novel. She hadn’t published a book in 1924 which may have been due to the research and work required for Simon the Coldheart. It’s also possible that she didn’t have a British publisher for the novel. Hutchinson had published her last two ‘Georgette Heyer’ novels in the UK and wuld have had an option on her next book and yet they did not publish Simon the Coldheart. For the first and only time in her life, Georgette Heyer’s new novel would appear in America before Britain. Small & Maynard had already published he Great Roxhythe and Instead of the Thorn and they produced a beautiful edition of Simon the Coldheart.

The first US edition of “Simon the Coldheart” by Georgette Heyer. The novel received good reviews in America.

The first US edition of “Simon the Coldheart” by Georgette Heyer. The novel received good reviews in America.‘She knows her history thoroughly and seldom takes liberties with it. She makes her knightly days live again, but, better, she makes Simon and Margaret live, who never lived before.’

Isabella Wentworth Lawrence, Boston Evening Transcript, 23 May 1925, Book Section, p.5.

Simon the Coldheart was the third of four Georgette Heyer novels published by US firm, Small & Maynard.

Simon the Coldheart was the third of four Georgette Heyer novels published by US firm, Small & Maynard.A new contract and a Tragedy

With Simon the Coldheart scheduled for publication in America, Georgette’s agent, L.P. Moore, set about finding a British publisher. Georgette had become dissatisfied with Hutchinson and was pleased when Moore secured her a contract with Heinemann for Simon the Coldheart. The terms were good with a £50 advance and a royalty rate beginning at 12½% and rising to 15%, 20% and 25% on sales of 7,000 to 15,000 books. This was good money for a book already written and ready for immediate publication. The Heinemann contract also had an option clause for a second unnamed novel. As Simon the Coldheart would not appear until October, this meant that Georgette had plenty of unpressured time to write a new book. She signed the Heinemann contract on June 15 1925 with no idea of impending tragedy.

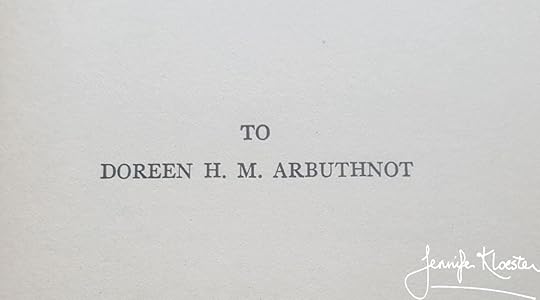

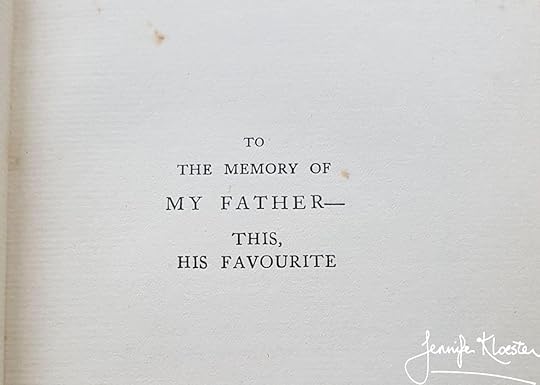

The very next day, on 16 June 1925, Georgette Heyer’s beloved father, George Heyer, suffered a massive heart attack and died in front of his daughter. It was an appalling tragedy. The shock of her father’s death would have a lasting impact on Georgette’s life and career and her son would later explain that she never fully recovered from it. The only public acknowledgement of the tragedy was small and subtle and consisted of an alteration in the printed dedication in Simon the Coldheart. The American edition had been dedicated to Georgette’s close friend, Doreen Arbuthnot; the UK edition was dedicated to the memory of her father.

Georgette’s dedication in the May 1925 US edition

Georgette’s dedication in the May 1925 US edition Georgette’s altered dedication in the October 1925 UK editionThe different dedications in Simon the Coldheart mark the death of Georgette Heyer’s father in June 1925

Georgette’s altered dedication in the October 1925 UK editionThe different dedications in Simon the Coldheart mark the death of Georgette Heyer’s father in June 1925Georgette’s relationship with Doreen Arbuthnot remains a mystery. It is not known where or when the two young women met or why Georgette dedicated Simon the Coldheart to her. Doreen’s real name was Dorothea and she was the great-niece of the Duchess of Atholl and of Georgiana, Countess of Dudley. She had grown up in a stately home in Sussex with her parents, Gerald and Mary, her two sisters, Cynthia and Frances, and a retinue of servants. Doreen’s father was the grandson of Sir Thomas Moncrieffe, 7th Baronet of Moncrieffe. Gerald was killed on the Somme in 1916 and Doreen’s mother Mary moved to a house in Kensington before King George V granted her a Grace and Favour apartment at Hampton Court Palace. Georgette must have thought very highly of Doreen to dedicate a book to her. Five years later, having felt compelled to alter the dedication in Simon the Coldheart, she also dedicated Barren Corn to ‘Doreen’.

Early suppression and a late reprieve

In the late 1930s, despite ten reprints in eight years, Georgette Heyer decided to suppress Simon the Coldheart. She had developed a strong dislike for several of her early novels and by 1940, with nearly thirty novels to her credit, she asked that six of her books including Simon the Coldheart no longer be published. In 1975, a year after her death, Georgette Heyer’s son, Sir Richard Rougier, was persuaded to reconsider his mother’s wishes regarding Simon the Coldheart. Upon reading his mother’s youthful work, Richard agreed to its republication and wrote an explanatory Foreword in which he explained his reasons for his ‘filial disobedience’. Today there are many readers grateful for Richard’s reappraisal of this delightful book. If you’ve never read Simon the Coldheart I recommend you give it a try. It isn’t one of Georgette Heyer’s Georgian or Regency novels but it’s still a compelling read.

May 22, 2020

Instead of the Thorn – A Daring novel

Instead of the Thorn was Georgette Heyer’s first attempt at writing a novel set in her own era. It was 1923, she was twenty years old, and as yet unmarried. Brought up by intelligent, educated parents, Georgette had been given free rein in her father’s library and by adulthood was familiar – in print at least – with love in its various guises. She was a natural observer of people and reading her early novels it is obvious that she had learned a great deal about male-female relationships. We do not know if she ever experienced a grand passion – though at sixteen she was said to have fallen in love with Harold Pullein-Thompson, sixteen years her senior and a friend and colleague of her father’s. Harold would later marry Joanna Cannan and she and Georgette would become close friends.

Instead of the Thorn 1923. Another very rare Hutchinson first edition.

Instead of the Thorn 1923. Another very rare Hutchinson first edition.Instead of the Thorn is the story of Elizabeth Arden, an intelligent but sheltered young woman, whose natural curiosity has been quashed from an early age by her narrow-minded and repressed Victorian maiden aunt. Elizabeth has no mother and her father is a self-absorbed, selfish man whose interest in his daughter only really begins when she grows up and begins to attract ‘the right sort’ of men. As a child Elizabeth has learned to suppress her true self in order to become the person she thinks others wish her to be. Only Mr Hendred, a kind friend of her father’s, sees through Elizabeth. He tries to help her see her self-deception but is unsuccessful for much of the novel. Elizabeth enters society and meets Stephen Ramsay, a brilliant author, handsome, debonair and, in the hierarchical world of 1920’s England, her social superior. Stephen finds Elizabeth’s innocence an allure he cannot resist and they are soon married. Unfortunately for Elizabeth, her aunt has ensured that she is not so much innocent as ignorant. Thrust into marriage without any understanding of sex, Elizabeth is horrified by the realities of intercourse. Although she tries to hide her revulsion, her true feelings gradually seep through, sullying the relationship until eventually her marriage fails. Elizabeth leaves Stephen to try and make a life of her own and thus begins her journey of self-discovery.

Georgette Heyer in the early 1920s, around the time of writing Instead of the Thorn. (used with permission)

Georgette Heyer in the early 1920s, around the time of writing Instead of the Thorn. (used with permission) Joanna Cannan, Georgette’s close friend and counsellor while she was writing Instead of the Thorn. (used with permission)

Joanna Cannan, Georgette’s close friend and counsellor while she was writing Instead of the Thorn. (used with permission)Instead of the Thorn is one of the rare Georgette Heyer novels in which sex is crucial to the story. Elizabeth’s ignorance of the physical act has a disastrous impact on her marriage. Her narrow and uninformed upbringing prevents her from asking about the “something in marriage that was dark and mysterious” though she

longed for the courage to confess ignorance and beg enlightenment. But years of training stood in her way, and the implanted belief that knowledge was wrong.

Instead of the Thorn, p.64

So Elizabeth recoils from sex, avoids it, and finds herself growing ever more repulsed by her husband’s desire for her. She cannot speak of her anxieties to him or to anyone else and this only exacerbates her struggles with married life.

‘physical contact grew less revolting, but no less unpleasant.’

‘Only when she slept by herself did she realize to the full how she hated to have Stephen with her.’

‘For as long as she continued to shrink from crude facts, and honesty, there could be no real intimacy between them.’

Georgette Heyer, Instead of the Thorn, Longman, 1929, pp 113, 143, 140

This ignorance of the realities of sexual intercourse was a very real experience for many woman (and some men) at the time and, although unmarried, Georgette Heyer was well aware of this. Shehad read Marie Stopes’s revolutionary (for the time) 1918 book, Married Love, but she also drew on the knowledge and experiences of her close friend, Joanna Cannan. Joanna – “J’anna” to Georgette – had married Harold Pullein-Thompson in 1918 and the couple had moved to a house in Marryat Road in WImbledon, not far from the Heyer’s. It was with Joanna that Georgette would discuss ‘the fortunes of Elizabeth Arden not once but many times’.

The formal dedication to Joanna Cannan whose ‘good counsel’ and kindness helped Georgette to write Instead of the Thorn

The formal dedication to Joanna Cannan whose ‘good counsel’ and kindness helped Georgette to write Instead of the Thorn The second printed decdication and a rare insight into the background and writing of one of Georgette Heyer’s many novels.Georgette felt sincere gratitude to Joanna Cannan for her help with Instead of the Thorn and publicly acknowledged it.

The second printed decdication and a rare insight into the background and writing of one of Georgette Heyer’s many novels.Georgette felt sincere gratitude to Joanna Cannan for her help with Instead of the Thorn and publicly acknowledged it.The long published dedication to Joanna Cannan is unique among Heyer’s novels for she never did it again. The sorts of heartfelt feelings which she expressed to her friend would later be confined to a few letters and the occasional hand-written dedication in one of her rare signed books. Joanna Cannan was one of Georgette’s few confidantes and perhaps the only person to whom Georgette could talk about sex and marriage – it being highly unlikely that she would have discussed such things with her usual confidante: her father. Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, was right when she described Instead of the Thorn as ‘a bold book for an unmarried girl of twenty-one, especially in those inhibited days.’

Georgette Heyer’s own first edition copy of Instead of the Thorn

Georgette Heyer’s own first edition copy of Instead of the Thorn First edition signed to Georgette’s friend, Joanna Cannan, using their nicknames ‘J’anna’ and ‘George’

First edition signed to Georgette’s friend, Joanna Cannan, using their nicknames ‘J’anna’ and ‘George’ First edition signed to Georgette Heyer’s agent, Leonard P. Moore, ‘the Thorn’s keenest admirer’

First edition signed to Georgette Heyer’s agent, Leonard P. Moore, ‘the Thorn’s keenest admirer’Georgette was in hospital recovering from surgery when the proofs for Instead of the Thorn arrived. She was enthusiastic about the novel and ‘delighted to hear that the Thorn is coming out fairly soon’. It is clear that she and her father had discussed her new book for Georgette confessed to her agent that, ‘Dad doesn’t think nearly as much of the book as you do’ and that she couldn’t ‘possibly puff off my own work.’ She did, however, have strong ideas about the book’s jacket:

‘As to the wrapper, I’m really not strong enough to have another quarrel with Hutchinson about their artist’s idiocy. I don’t know what I want, but I think they’d better have Elizabeth on the jacket, and leave Stephen out of it. Elizabeth is like Emma Hamilton, only, of course, darker, and not so roguish. If they want to go in for symbolism they’d better have Aunt Anne and Stephen dragging the poor girl different ways. How awful! Failing that – I do have original ideas, don’t I? – what about slicing Elizabeth in half, and making one half look Victorian, and the other modern? Don’t slay me! I can’t help it! Seriously, Hutchinson produced a book last autumn by Ethel Boileau, called the Box of Spikenard, and the wrapper design was most attractive. It was just a sketch of a girl’s head, uncoloured.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter dated 8 September 1923, Tulsa Archive.

The jacket design which Georgette Heyer admired and recommended to her agent, L.P. Moore.

The jacket design which Georgette Heyer admired and recommended to her agent, L.P. Moore. The final jacket of Georgette’s own novel which is in keeping with her ideas for its design.

The final jacket of Georgette’s own novel which is in keeping with her ideas for its design.Instead of the Thorn is not what most readers have come to expect from a ‘Georgette Heyer novel’, but it is a readable story which offers a window into upper middle-class life in 1920’s England. It is also an interesting reflection of the world in which Heyer herself lived. A thoughtful book, its subtle commentary on class, morality, marriage and sex offer a fascinating and often uncomfortable contrast with today’s world. Heyer writes tellingly of the kind of social scene in which she moved after the First World War. There is both discomfort and enjoyment in her protagonist’s experience of the afternoon teas, dances, theatre visits and other social events and one cannot help wondering about Heyer’s own experience of the social round. Again and again in the novel there are moments where the reader wonders: ‘is this Georgette Heyer speaking for herself?’ Certainly, Instead of the Thorn – like her three later contemporary novels – were one way for her to work through some of her ideas and reactions to her own experiences as a woman in 1920’s England. Here are a few telling moments:

‘The man takes and the woman gives. Leastways, I’ve always found it so.’

‘It’s a poor woman who’s got no man to manage’

‘The man that can’t be managed don’t exist’

‘You see, dearie, a man’s selfish. He can’t help it; he don’t have to bear what we bear. At the best he’s stupid when it comes to understanding how we women feel. We don’t really like him any the less for that.’

‘My dear, don’t you get thinking this is a fair world for women, because it isn’t.’

Georgette Heyer, Instead of the Thorn, Hutchinson 1923.

Leaving aside the many objectionable (to modern sensibilities) aspects of Elizabeth’s life and experiences, Instead of the Thorn remains a novel about an individual’s self-deception, self-discovery and eventual transformation. Perhaps most tellingly of all is the Biblical quotation from which the book takes its title:

‘Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree and instead of the briar shall come up the myrtle tree’

Isaiah 5:13

The American first edition of Instead of the Thorn

The American first edition of Instead of the Thorn Praise for Georgette Heyer on the first edition dustjacket

Praise for Georgette Heyer on the first edition dustjacketMay 19, 2020

Why I (still) Read Georgette Heyer

I’ve had a fortunate life but I still find it hard sometimes – I mean, who doesn’t? Unexpected things happen (like worldwide pandemics!), people let you down, things don’t turn out as planned, and hurt and tragedy come to all of us. I spent six of the last eight years in chronic pain – the kind that kept me tossing and turning for hours when I should have been sleeping and which made daily life very difficult. I tried every suggested remedy and saw all kinds of medicos before I finally found relief through weight training. During those challenging years, one escape from pain was laughter. And a writer I can always depend on to make me laugh aloud is Georgette Heyer (you can peruse her books here).

The remarkable world created by the inimitable Georgette Heyer led me to write

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

The remarkable world created by the inimitable Georgette Heyer led me to write

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World

Though I’ve written two books about her and read her novels countless times, Heyer’s stories always feel fresh to me. She’s so brilliant with dialogue and her characters are alive. Her plots are often ingenious and her sense of humour is delicious. Just thinking about some of her stories makes me smile. The Unknown Ajax for example. During those pain-filled years I was gifted an Audible subscription. I discovered, among other great Heyer audio books, the wonderful Daniel Philpott reading The Unknown Ajax.

The unforgettable and very funny Unknown Ajax

The unforgettable and very funny Unknown AjaxActually, ‘reading’ doesn’t come near to describing his rendition of this brilliant book. I don’t think I’d ever fully appreciated the genius of Heyer’s plot and characters in The Unknown Ajax until I heard it read aloud by Mr Philpott. He’s a genius with accents and his broad Yorkshire is superb. He makes each character distinct and the ending is magnificent. Though I’ve read the novel a dozen times, I laughed as though hearing it for the very first time. An incredible escape from trouble and pain – as good books always are. These days I re-read Georgette Heyer for pure pleasure but, as so many of her readers know, she’s a shining light in the dark (pandemic) times too.

Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novels

Georgette Heyer’s bestselling novels

May 15, 2020

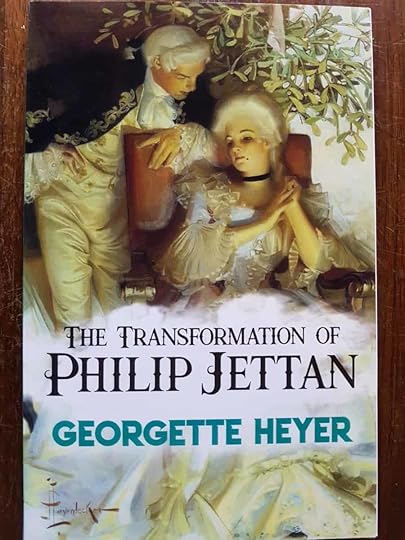

The Transformation of Philip Jettan

Georgette Heyer’s third novel was unique. It is her shortest book, she wrote it in three weeks and it was her only book written under a pseudonym. The Transformation of Philip Jettan by “Stella Martin” was published in April 1923 and it’s possible that only her closest friends and family knew it was really a Georgette Heyer novel. We don’t know exactly why she chose to hide her identity for this, her third book, though it may have had something to do with her being under contract to Hutchinson at the time. The previous year they had published The Great Roxhythe and would publish Heyer’s first contemporary novel, Instead of the Thorn, in November 1923. For Heyer to publish another novel with a different publisher would undoubtedly have been frowned upon and may even have been a breach of contract – a powerful reason to publish the new book under another name.

The first edition dustjacket for Georgette Heyer’s third novel – her only book published under a pseudonym.

The first edition dustjacket for Georgette Heyer’s third novel – her only book published under a pseudonym. Much misunderstood: Mills & Boon

The Transformation of Philip Jettan was published by Mills & Boon which, in those days, was still a large general publisher. Years before the company instigated its famous romance brand, Mills & Boon published all kinds of books, including travel guides, cookery books, Shakespeare’s plays, novels, biographies, memoirs, sporting guides, self-help books, financial texts and a variety of reference books about history, psychology, religion and the natural world.

Founders Gerald Mills and Charles Boon were commmitted to general publishing, including fiction of a ‘popular’ and a ‘quality’vein. The latter included the great and the near-great… P.G. Wodehouse, Hugh Walpole, Victor Bridges, Jack London, E.F. Benson, Georgette Heyer, Denise Robins, and Constance Holme were all published by the firm.

Joseph McAleer, Passion’s Fortunes: the Story of Mills & Boon, p.3.

It wasn’t until 1930 that Mills & Boon began to specialise in romance fiction but the decision marked a watershed in the company’s history. Already a successful publisher, they would eventually reach the heights of publishing success and their name would become so instantly recognisable that in 1997 it would be added to the Oxford English Dictionary with the definition: “romantic, story-book”. The firm built its success on the fact that readers love romance. Today, romance fiction accounts for almost fifty per cent of all novels sold and, while there are still those who will deride genre fiction, Mills & Boon knew better:

You see, we never despised our product. I think this is highly important. A lot of people who publish romantic novels call them ‘funny little book’s that make a bit of profit. We never did that. We never said this was the greatest form of literature, but we did say that of this form of literature, we were going to publish the best.

John Boon, Mills & Boon Chairman, son of co-founder, Charles Boon,

Georgette Heyer’s first edition copy with the Mills & Boon insignia on the cover.

Georgette Heyer’s first edition copy with the Mills & Boon insignia on the cover. The spine with the Georgette’s pseudonym in bold type.

The spine with the Georgette’s pseudonym in bold type. Some well-known names appeared in the advertising material at the back of the novel.First editions of Georgette Heyer’s only pseudonymous novel are extremely rare.

Some well-known names appeared in the advertising material at the back of the novel.First editions of Georgette Heyer’s only pseudonymous novel are extremely rare. This was her own copy which Georgette probably gave to her father.

In 1923, The Transformation of Philip Jettan was one of more than one hundred novels listed in the Mills & Boon catalogue. It would be interesting to know if the firm’s founders ever knew that their one-off author ‘Stella Martin’ was actually Georgette Heyer; it would be even more interesting to know for certain why she chose to use a pseudonym. So far the only other known composition which Georgette published as ‘Stella Martin’ was her 1925 short story entitled ‘The Old Maid’, a copy of which may once again be read in Acting on Impulse, a collection of Heyer short stories published in 2019.

Written in three weeks

Though this was her second published novel set in the eighteenth-century, The Transformation of Philip Jettan was actually Georgette Heyer’s third story set in that era. Her second eighteenth-centruy novel was really These Old Shades which she’d begun writing in 1922, at the age of nineteen. That story was intended as a “sequel” to The Black Moth (more on These Old Shades on 5 June 2020) and by January 1923 it was nearly finished. At some point during the writing of that book, Georgette must have been struck by the idea for The Transformation of Philip Jettan for she wrote the new novel in just three weeks. A light-hearted romantic story, its countrified hero, Philip Jettan, is in love with the fair Cleone. She loves him, but wishes he were more fashionable. Angered by his beloved’s rejection of him as he is, Philip travels first to London and then to Paris in order to effect his ‘transformation’. As always in a Georgette Heyer novel, there is more to the story than meets the eye.

The original final chapter which was deleted from the 1930 Heinemann reprint.

The original final chapter which was deleted from the 1930 Heinemann reprint. A reprint of the complete novel, with the missingfinal chapter, now available in the USA due to the 95-year copyright rule.

A reprint of the complete novel, with the missingfinal chapter, now available in the USA due to the 95-year copyright rule.Restoration Comedy

Perhaps one of the reasons that Georgette’s eighteenth-century novels have remained so popular is their energy. Georgette’s father had brought her up on a rich literary diet and among her favourite things to read were the Restoration comedies of playwrights such as Sheridan and Congreve. From them she learned much about comedies of manners, wit and wordplay, and also became familiar with the rake, the fop and the cross-dressing heroine – hugely popular figures in the seventeenth century – and all of whom Georgette would use many times in her own novels. There is an unmistakeable spirit of Restoration Comedy in The Transformation of Philip Jettan with its aristocratic affectations, its gentle ridiculing of the marriage mart, and its way of poking fun at Philip as both fop and rake. These As Diane Maybank explains in her excellent article,

‘The comedy of manners was Restoration comedy’s most popular subgenre. Although they ultimately uphold the status quo, these plays scrutinise and ridicule upper-class society’s manners and rules of behaviour, providing an up-to-the-minute commentary on class, desire and the marriage market.

Diane Maybank, ‘An Introduction to Restoration Comedy’, British Library, 21 June 2018

Her father’s influence?

Of all of Georgette Heyer’s novels, The Transformation of Philip Jettan is the only one to feature poetry. Once in Paris, Philip enthusiastically embraces his transformation and develops a passion for fashion, fencing and furbelows. To the mock horror of his aristocratic new friends, he also takes to writing poetry – in both English and French – and worse, insists on reading his poems aloud to them. It is here that one suspects that Georgette’s father’s penchant for poetry makes itself felt. George Heyer loved writing poetry and among a collection of twenty of his published and unpublished verses are a ballade, a sonnet and a rondeau. In The Transformation of Philip Jettan a rondeau written in French features midway through the book when Philip arrives ready to entertain his friends with a recitation. George Heyer was himself a fluent French speaker and although Georgette also spoke French, if he did not write the poems for her novel in their entirety, her father would undoubtedly have had a hand in their creation:

Into the room came, Philip, a vision in shades of yellow. He carried a rolled sheet of parchment tied with an amber ribbon. He walked with a spring, and his eyes sparkled with pure merriment. He waved the parchment roll triumphantly.

Saint-Dantin went forward to greet him. "But of a lateness, Philippe," he cried, holding out his hands.

"A thousand pardons, Louis! I was consumed of a rondeau until an hour ago."

"A rondeau?" said De Vangrisse. "This morning it was a ballade!"

"This morning? Bah! That was a year ago. Since then it has been a sonnet!"

...

"Devil take your rondeau," cied the Vicomte...

"A l'instant!" Philip untied the ribbon about his rondeau and spread out the parchment. "I insist that you shall listen to the product of my brain!" ...

"Cette petite perle qui tremblotte

Au bout de ton oreille, et qui chuchotte

Je ne sais quoi de tendre et de malin ...

And so Philip continues for three verses until, as he pause for the climax, he is rudely interrupted by one of his friends, with a witty alternative ending at which point Philip throws the parchment at his head. There are some sparkling moments in Heyer’s third published novel, but among her many novels it is a more a tasty hors-d’oeuvre than the feasts which were to come.

“I beg your acceptance, darling, of this elegant trifle. Dordette”

“I beg your acceptance, darling, of this elegant trifle. Dordette”The first edition in Georgette’s library most probably signed to her father using her family nickname, “Dordette”.

May 12, 2020

Historically Speaking – Georgette Heyer’s Regency Novels

Almost fifty years after her death Georgette Heyer remains a perennial bestseller. With over thirty million books sold and most of her 56 novels still in print, she is loved around the world. Heyer is best known for her historical novels. Although she wrote short stories and books in different genres and time periods – including contemporary novels, medieval stories and detective fiction – she is best known for her historical fiction set in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is these latter two eras which were her particular forte and it is with the English Regency period that her name has become synonymous.

The first edition of the novel that inspired a genre. Georgette Heyer’s Regency Buck with the pugilist on the spine.

The first edition of the novel that inspired a genre. Georgette Heyer’s Regency Buck with the pugilist on the spine.The English Regency 1811-1820

Of her fifty-five novels published during her lifetime, twenty-six are set specifically within the English Regency period of 1811 -1820 when King George III had been declared mad and his son George, Prince of Wales, was named Regent and ruled in his father’s stead. Heyer grew to love the era – not least because it was the time in which Jane Austen wrote and in which Austen’s novels are set. Heyer’s reading of Austen gave her a ‘way in’ to the period but she also read widely among the primary sources available to her at the time. She read contemporary Regency texts, including letters, diaries, travelogues, autobiographies and miscellaneous works about life and culture in the period. She loved being able to include in her novels the ‘recondite details’ or ‘sudden bit of erudition that every now and then staggers the informed reader’. Heyer had a remarkable ability to effotlessly distil a wealth of historical detail into her fictional stories.

Georgette Heyer’s personal copies of Jane Austen’s juvenilia, novels and letters.

Georgette Heyer’s personal copies of Jane Austen’s juvenilia, novels and letters.Inevitable influences

Like all authors who write about a past era, Heyer could never divest herself of the perceptions and influences of her own time. She was born into the Edwardian era and raised by Victorian parents; her formative years were spent reading Shakespeare, Austen, Kipling and Dickens, as well as the Greek plays, the Renaissance poets and the great masters of Restoration comedy such as Sheridan. The wit and style she imbibed from these great writers would influence and inform her own writing. Heyer developed strong views about the world and grew up believing in Britain and the Empire. She also understood and accepted the English social hierarchy and, like her father and grandparents before her, strove to climb the social ladder. Heyer believed in manners and morals, hard work and tradition but she also believed in women’s intellectual independence and this, among other twentieth-century ideas, inevitably permeate her novels.

Georgette Heyer’s leatherbound Life in London 2-volume set. Part of what remains of her vast research library.

Georgette Heyer’s leatherbound Life in London 2-volume set. Part of what remains of her vast research library.Bringing the Regency to Life

Heyer’s Regency world is a deliberately narrow one. Leaving aside the unlikely number of dukes, earls and viscounts, her novels come to life with their depictions of upper-class Regency life, its fashion, modes and manners. She had an extraordinary memory and her wide reading and research meant that she had the ephemeral detail at her fingertips. She also kept an eclectic set of notebooks, recording her discoveries in her characteristic handwriting and often tracing useful pictures of clothing or carriages or money or postage stamps into the books. She was frequently able to weave the historical details into her novels so deftly that it can sometimes be difficult to separate the historical from the fictional.

What remains of Georgette Heyer’s famous notebooks

What remains of Georgette Heyer’s famous notebooks Heyer’s notes on pugilism and some of the great fighters of the era and

Heyer’s notes on pugilism and some of the great fighters of the era and Heyer’s ability to ‘re-create the past’ is due, in large measure, to her immersion in the primary sources. Although she read widely among secondary sources, she preferred material from the period. Writers such as Fanny Burney, Thomas Creevey, Charles Greville, Sarah Lennox, the Duke of Wellington, Captain Gronow and Elizabeth Wynne were among her preferred authors. She had a vast reference library which included original texts such as Blackmantle’s English Spy; The Hermit in London; Harriette Wilson’s memoirs, all of Wellington’s Dispatches, Pierce Egan’s Life in London and many dictionaries of costume and language. She made good use of Francis Grose’s famous 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: Buckish Slang, University Wit and Pickpocket Eloquence (for a fascnating article read here). She also used contemporary magazines, guidebooks, sporting and domestic tomes. Heyer was meticulous in her description of Regency fashion, furniture, carriages, hunting, fencing, fist-fighting, gambling and domestic management. Her ephemeral detail helped to create a sense of the Regency that remains unmatched in fiction. Today her period dialogue has become a byword among historical novel readers and writers.

Heyer made good use of Francis Grose’s famous dictionary

Heyer made good use of Francis Grose’s famous dictionary A facsimile of the original title page

A facsimile of the original title pageHeyer had no formal training in history. Until she was thirteen she was educated at home where her father, George, encouraged her love of reading and writing. He was a writer himself and father and daughter often read and edited each other’s work. It was only when her father went to war in 1915 that Heyer finally went to school. There she outshone her peers and found her intellectual equals among the teaching staff. She did not go to the university. Instead, her approach to history was influenced by the great literary historians: Edward Gibbon, Thomas Macaulay, James Froude and Thomas Carlyle, who were still widely read and admired when Heyer was young. From them she learned the importance of original sources. From historical novelists such as Walter Scott, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Mrs Gaskell, Alexandre Dumas (père), Charlotte Yonge and William Thackeray she learned how to invoke a vivid sense of a period, its key players and events. Although she never thought of her novels as serious history, Heyer took the history that she wove into them very seriously indeed.

May 7, 2020

The Great Roxhythe 1922 & 1929

The original 1922 first edition published by Hutchinson who were happy to promote Georgette’s earlier work on the cover.

The original 1922 first edition published by Hutchinson who were happy to promote Georgette’s earlier work on the cover.Georgette Heyer’s second novel

Originally published in November 1922 , The Great Roxhythe was Georgette Heyer’s second novel and her first book for her new publisher, Hutchinson. Very different from her first book The Black Moth – a lively, romantic adventure published by Constable the previous year – The Great Roxhythe was Heyer’s first attempt at a more serious historical story. Set during the reign of King Charles II after the Restoration, the story begins in 1670 and navigates the historical maze of the next ten years of wars, treaties and political intrigue between England, France and Holland. Central to all of this is ‘the King’s favourite’, Heyer’s main character, the fictional Marquis of Roxhythe whom the King calls “Davy”. It is Roxhythe who dominates the novel:

‘He was the perfect courtier, combining grace and insolence even more successfully than His Grace of Buckingham. His bow was incomparable; his air French; his wit spicy; his tailoring beyond words remarkable. He was said to be fabulously wealthy, even in those days of splendour and unlimited extravagance. All this alone was enough to gain him popularity, but yet another asset did he possess. This was the ear of the King.’

The Great Roxhythe 1922 p.12.

The Marquis of Roxhythe

Like the Duke of Andover in The Black Moth, Roxhythe is another forerunner to the elegant, imperturbable men of fashion who would eventually populate Heyer’s Regency novels. The Marquis of Roxhythe is a commanding figure – ‘the King’s favourite and the ladies’ darling, and his name was on many lips.’ So ends the first paragraph of the 1929 Heinemann reprint – a very different opening from the original 1922 Hutchinson edition. In its earliest incarnation The Great Roxhythe had a Contents page and an opening chapter entitled ‘The King and His Brother’, in which Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York (later James II) discuss King Louis of France, the treaty with Holland, and James’s fervent desire to see Catholocism restored to England. In the 1929 Heinemann reprint this chapter has been expunged and Georgette has written a new opening for Chapter Two: ‘The King and His Favourite’ and rearranged several of the chapter’s original opening paragraphs. Thus it is Roxhythe and not Charles II who holds the stage from the beginning of the revised novel.

The 1929 Heinemann reprint.

The 1929 Heinemann reprint. The 1922 first edition had a table of contents. The 1929 reprint did notHeyer’s new publisher, Heinemann, republished The Great Roxhythe in January 1929 with a new cover and without the original first chapter.

The 1922 first edition had a table of contents. The 1929 reprint did notHeyer’s new publisher, Heinemann, republished The Great Roxhythe in January 1929 with a new cover and without the original first chapter. Only nineteen

Lovers of Georgette Heyer’s Georgian and Regency novels will find thatThe Great Roxhythe makes for very different reading but I think it is worth reading at least once. One good reason to read The Great Roxhythe is for what it tells us of the youthful Georgette. She was only nineteen when she wrote the book and, for all its faults, it remains an engaging and readable story. The Great Roxhythe would be an ambitious book for any author, but for a teenager it is a genuine achievement. Heyer reveals a level of perception not common in adolescents but which is evinced in sentences like: ‘When men murmur, it is but a short step to shouting, and from shouting it is an even shorter step to rebellion’ and ‘It is a game, Christopher, called politics.’ Throughout, the novel strongly reflects Heyer’s innate intelligence, love of history and ear for dialogue.

An Unusual Novel

In the Heyer canon, The Great Roxhythe is unusual both in its historical breadth, and detailed depiction of so many historical figures but it also stands alone as the only one of Heyer’s many novels that has no central romance. Roxhythe is an enigmatic figure, with several female friends but Heyer does not give him the kind of romantic attachment that would give her readers such pleasure in later books. In The Great Roxhythe the greatest love is that which Roxhythe has for his charming but reckless King, while Roxhythe’s young secretary nurses a heartfelt, yet naive love for his enigmatic employer. These relationships are an important part of what drives the story but to the modern reader unfamiliar with the nature of sixteenth-century courtly love they may seem strange and at times uncomfortable.

Literary Aspirations

The Great Roxhythe also reveals something of Georgette Heyer’s literary aspirations. Throughout her life, and despite her immense success, Georgette Heyer would be forever plagued by the idea that she should ‘write a serious novel’ (aka a ‘worthy’ novel). In some ways and perhaps ironically, her second book, The Great Roxhythe, is the closest she ever came to fulfilling that ambition, though it was a novel that would deeply disappoint her. Even before the reviews appeared Heyer had already decided that she did not like The Great Roxhythe. She inscribed her own first-edition copy of the book with these telling words: “This Immature, ill-fated work.” Towards the end of her life Heyer wrote to an American fan in answer to a query about Roxhythe, explaining that, ‘This very jejune work, written when I was nineteen (and just the kind of book you’d expect from an over-ambitious teenager!) was withdrawn, at my own urgent request from circulation years ago.’

The flyleaf of Georgette Heyer’s personal copy of her second novel, The Great Roxhythe

The flyleaf of Georgette Heyer’s personal copy of her second novel, The Great RoxhythePublished on both sides of the Atlantic

Published by Hutchinson in the UK in November 1922 and by Small Maynard in the USA in June 1923,The Great Roxhythe was reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic with lengthy reviews in The New York Times Book Review and The Boston Evening Transcript and shorter ones in The Times Literary Supplement and The Springfield Republican. The novel was moderately well-received with some encouraging praise for Heyer’s picture of Charles II and others:

Charles ‘stands out rather more clearly drawn than is usual’

‘There are in the book a number of clever sketches of men and women; most notable, perhaps, the portrait of the Prince of Orange’

Thanks to her neat dialogue, Miss Heyer succeeds in making [Roxhythe] and entertaining specimin of his class…’

The Boston Evening Transcript; The New York Times Book Review; The TImes Literary Supplement

But she also received some strong criticism.

‘it suffers somewhat from having too large a canvas, and from a certain monotony in the telling. .. the book is very much too long; there is a great deal of repetition, many incidents and conversations which do little to develop character, while of story there is almost none.’

‘She has been afraid to be too serious, and her intrigues become little more than a single figure, talking most of the time with such elegant inscrutability that the reader, just as much as any of those whom he wishes to deceive, is left puzzled as to what he is about.’

The New York Times Book Review 24 June 1923, p.17 & The TImes Literary Supplement 14 December 1922

Small Maynard, an excellent US publisher

The American first edition published by Small Maynard in 1923

The American first edition published by Small Maynard in 1923 The American first edtion signed by Georgette to her friend Joanna Pullein-Thompson (nee Cannan)The Great Roxhythe ws Georgette’s first novel published by Small Maynard, her second American publisher after Houghton Mifflin.

The American first edtion signed by Georgette to her friend Joanna Pullein-Thompson (nee Cannan)The Great Roxhythe ws Georgette’s first novel published by Small Maynard, her second American publisher after Houghton Mifflin.Suppression

It is hard to imagine the effect of these critiques on the young Heyer. She had achieved a genuine success with her first book; her career was just beginning and she had only recently turned twenty when The Great Roxhythe was published. Despite having inscribed her personal copy with an acknowledgement of its apparent failure, she must have been disappointed – if not deeply affected – by the reviewers’ comments. Of course, this did not stop the book from selling. Heinemann alone reprinted it five times between 1929 and 1935. In the late 1930s, however, Heyer asked that the novel be suppressed. Heinemann agreed, but in 1951, Heinemann, apparently oblivious to her request (or perhaps deliberately ignoring it) reissued The Great Roxhythe as part of its Uniform Edition of Georgette Heyer novels. Heyer was appalled when she learned of their intention and immediately wrote to her close friend and publisher, A. S. Frere, begging him not to republish The Great Roxhythe.

The 1951 Uniform edition of The Great Roxhythe. Georgette Heyer was appalled by its republication.

The 1951 Uniform edition of The Great Roxhythe. Georgette Heyer was appalled by its republication.‘Please, Perlease don’t do this!’

When I returned DUPLICATE DEATH to Mr Oliver, I asked him for copies of what I took to be the Uniform Edition of several of my back numbers, having observed that they figured handsomely on the latest royalty statement, and not having seen them in their new dresses. Today I received from him THE [RELUCTANT] WIDOW and the MASQUERADERS, together with a letter, telling me that “we are having prepared…THE CORINTHIAN, SIMON THE COLDHEART, THE BLACK MOTH, and THE GREAT ROXHYTHE.

PLEASE, PERLEASE don’t do this! I thought we were agreed that, with the exception of the SHADES, over which I have no control, everything prior to the MASQUERADERS should be allowed to sink into decent oblivion. CORINTHIAN, yes. The other three, ten thousand times, NO! why on earth have you chosen to do these lethal and immature works when the CONVENIENT MARRIAGE, TALISMAN RING, ROYAL ESCAPE, and PENHALLOW still await attention? When these are on the market again, I should prefer to see them reissued rather than those childish and utterly frightful books put out again. Include in this category, if you please, POWDER AND PATCH!

I hope so much that it may not be too late to stop this. It will embitter my life!

Georgette Heyer to A.S Frere, letter, Frere Archive, 12 April 1951

The best and the worst

To her great regret and lasting chagrin, publication of the Uniform edition of The Great Roxhythe went ahead. Today, Heyer’s second novel tends to polarise readers. In her 1984 biography, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Jane Aiken Hodge described The Great Roxhythe as ‘probably the worst book Georgette Heyer ever wrote’, whereas an online reviewer declared it ‘The very BEST of Heyer’ explaining that, ‘It veers away from the usual light-hearted, unrealistic romances and plunges into the politics and intrigue of the age of Charls II, and it deals with the relationships between men and women in a less sentimental (and more realistic) manner. Slow, complex and mature.’

Another reader said that it was not up to Heyer’s ‘usual standards’ – a comment which should perhaps remind us thatThe Great Roxhythe was only her second novel and in 1922 Georgette Heyer did not yet have a ‘standard’.

May 4, 2020

My favourite Georgette Heyer novel…

A question I am often asked by both Heyer- and non-Heyer readers is “Which is your favourite Georgette Heyer novel?” It’s an excellent question and one which, in the hope of suggesting a book you might enjoy reading during self-isolation because of the Covid-19 pandemic, I will try to answer here.

Some of Heyer’s bestselling novels. By the late 1950s her publisher was printing 100,000 copies of her first editions.

Some of Heyer’s bestselling novels. By the late 1950s her publisher was printing 100,000 copies of her first editions.My first Heyer was one of her most famous novels, These Old Shades, and since its first publication in 1926 it has remained a firm favourite across five generations of readers. It was recommended to me by the woman who ran the tiny YWCA library in a remote town in the Papua New Guinea jungle. I’d never heard of Georgette Heyer but I took the book home and began reading. Little did I know that that book would mark the beginning of a life-changing love affair! I loved the story of Léonie and Justin Alastair, Duke of Avon, and in those years spent so far from home I read their story many times over. I also devoured every other Heyer novel in the library and on every R&R trip home I hunted the bookshops looking for any Georgette Heyer books I hadn’t yet read. I still have some of those original purchases, although many of them have fallen apart and have had to be replaced with lovely new editions. Over the years since then my favourite has shifted and changed as I have read and re-read my Heyer novels. I have often tried to pinpoint my favourite Heyer but must confess that it is no easy task when so many are so good.

A fascinating place, Papua New Guinea was a very different world and culture from the court of Louis XV

A fascinating place, Papua New Guinea was a very different world and culture from the court of Louis XV  The book that introduced me and so many other readers to Georgette Heyer.Such an extraordinary contrast. I loved my time in PNG and will always be glad that it was there that I discovered Georgette Heyer’s novels.

The book that introduced me and so many other readers to Georgette Heyer.Such an extraordinary contrast. I loved my time in PNG and will always be glad that it was there that I discovered Georgette Heyer’s novels.For a long time my favourite was Cotillion with its four couples moving through an intricately-woven plot echoing the movements of the dance for which the novel is named. The book features Freddy Standen: kind, amiable and, perhaps surprisingly, one of my most beloved (along with his father, Lord Legerwood) characters in all of Heyerdom. My first reading of Cotillion was one of the first times that Georgette Heyer made me laugh out loud. The second time was reading the ending of The Unknown Ajax and that book soon became my new favourite Heyer. To this day, I need only to think of Lady Aurelia sweeping into the room and declaring herself a ‘mere female’ to laugh, and when I recall the scene with Hugo and Polyphant and poor Claude, prostrate and moaning on the couch, it always makes me chuckle.

A few of the Pan covers of Heyer’s novels. Georgette would have disliked this cover of The Grand Sophy but over time the Pan covers improved and eventually won her approval.

A few of the Pan covers of Heyer’s novels. Georgette would have disliked this cover of The Grand Sophy but over time the Pan covers improved and eventually won her approval.However, the ending of The Grand Sophy with its Gothic manor house, oblivious poet, distracted Spaniard and flock of ducklings also makes me laugh aloud, as does the scene when Sophy kidnaps sanctimonious Eugenia Wraxton and drives her down St James’s Street past the gentlemen’s clubs. And then there’s Augustus Fawnhope, that beautiful young man with the face of an angel and the brain of a pea-goose and who is the perfect foil for the capable and attractive Lord Charlbury (excellent husband material) who you can’t help cheering for as he tries to navigate Sophy’s many schemes. This is a novel I have read over and over and for the longest time it was my absolute favourite.

Of course, I hadn’t yet read Sylvester, with the priceless Sir Nugent Fotherby and his tortuous encounter with young Edmund and his ‘Button’. Such is the brilliance of its plot and clever ending that I’m grinning as I write this. For a few years Sylvester was my favourite and the book I would choose to take to a desert island if I could only take one. The heroine, Phoebe, is such a heartfelt, beautifully-drawn character and there’s so much in Sylvester to move me. It also has a clever plotline based on a real-life event. Heyer often found inspiration in the historical realities of the Regency era and I suspect she very much enjoyed the story of Lady Caroline Lamb’s scandalous first novel, Glenarvon, for she put it to good use in Sylvester.

Heyer’s own personal favourite among her many novels was Friday’s Child, It’s an understandable choice because the plot is another of her clever, intricate creations and the characters are wonderful. From the first scene, where Sherry tries to woo the Incomparable, to the last, where he finally finds his Hero, the novel is populated with living, breathing people who remain with the reader long after the book is finished. Among them is Ferdy Fakenham, the man who would later inspired Heyer’s creation of Freddy in Cotillion. Ferdy almost steals the show in Friday’s Child over his determination to tell the hero about Nemesis, the goddess of retribution. For those in the know, the Nemesis joke will always provoke laughter.

Laughter is one of the hallmarks of the Georgette Heyer reading experience and it has long been one of my personal measures of how much I love her novels. And yet, as I have grown older and changed and (perhaps) acquired a little wisdom, her books also seem to have grown and changed. Books of hers that I liked well enough at first have now become more beloved and better understood. This, I believe is one of the reasons why Heyer’s novels endure. Her novels are not just witty and entertaining, they also each contain enduring truths about human nature. One book which I did not love when I was younger, but which has now become one of my all-time favourites, is A Civil Contract. Along with Venetia (another top five favourite), I believe A Civil Contract to be among Heyer’s greatest achievements. This quiet, elegantly-written novel, is Heyer at her most thoughtful, her most empathetic, her most perceptive. The relationship between Jenny Chawleigh – intelligent, pragmatic, loving – and Adam Deveril – kind, self-sacrificing, steadfast – is deeply moving and I have grown to love this book until it has become my favourite among her many wonderful novels.

Georgette Heyer’s personal favourite

Georgette Heyer’s personal favourite One of Heyer’s most perceptive books.

One of Heyer’s most perceptive books. Like its heroine, The Quiet Gentleman is often overlooked but well worth reading.

Like its heroine, The Quiet Gentleman is often overlooked but well worth reading.Of course, as I write this I am also thinking of Drusilla in The Quiet Gentleman and how much I love her steady evolution into the heroine of the piece. And of Hester Theale, the unlikely but glorious heroine of Sprig Muslin. Then there’s Arabella and the riveting scene where Arabella entreats Mr Beaumaris to save Jemmy the climbing-boy, or Frederica when Charis enters the ball-room in her homemade dress and then later when the Marquis of Alverstoke endures days of privation at an inn in order to support the woman he loves, or Black Sheep with Miles Calverleigh and Dolly the Dasher, or The Foundling with the gormless Belinda and the young Duke of Sale, or Devil’s Cub when Mary shoots Vidal, or The Convenient Marriage with Horry’s stammer and her eyebrows.

So many memorable moments, so many wonderful stories, and so many unforgettable characters. In the end, it’s impossible to choose just one favourite Georgette Heyer novel because so many of them are just so good. Their characters live for the reader, their plots are compelling, the dialogue sparkles, and there is joy and comfort and pure satisfaction between the covers. And I haven’t even told you about today’s favourite, The Talisman Ring…

May 1, 2020

The Black Moth – from teen novel to enduring bestseller

Georgette Heyer turned 17 in August 1919. Some months later, her younger brother Boris became seriously ill. By February 1920 he was recovering but it was felt that a change of scene would do him good. Sea air was thought to be an excellent remedy and so the Heyer family left Wimbledon for Hastings on the English south coast so that Boris could convalesce. Though a pretty seaside town, Hastings did not offer much in the way of amusement for the teenage Georgette, and Boris, too, was bored. And so, to alleviate the invalid’s ennui, his clever sister made up a story…

Hastings Pier in 1920. Georgette and her family chose Hastings for Boris’s convalescence. Hastings Pier Archive Copyright unknown.

Hastings Pier in 1920. Georgette and her family chose Hastings for Boris’s convalescence. Hastings Pier Archive Copyright unknown.‘I was 17 when I started to write my first book … and I originally started the book as a serial-story to relieve my own boredom and my brother’s

Georgette Heyer, letter to her publisher, 1962

“Wildly readable”

The story was enthralling. Day by day, episode by episode, the young Georgette regaled her brothers with the story of Jack Cartstares, disgraced Earl of Wyncham, and his many adventures. Sacrificing his home and title, Jack has become a highwayman with a charming alter-ego in Sir Anthony Ferndale. There would be sword fights and romance and an abduction with a desperate race at the end to rescue the heroine. One can imagine Boris and his younger brother, Frank (then aged seven), held in thrall as their sister told them the “wildly readable” story of the earl turned highwayman and his encounters with his dastardly, debonair enemy, “Devil” Belmanoir, Duke of Andover. It is the duke, “clad in his customary black and silver and with his raven hair unpowdered”, who, like “a black moth”, would give the story its title. The Black Moth entranced its young audience and Georgette went on and on writing until the story was finally finished.

Georgette with her brothers Boris and Frank around the time of writing The Black Moth.

Georgette with her brothers Boris and Frank around the time of writing The Black Moth.Only seventeen

There are not many seventeen-year-old authors whose first novels are considered worthy of publication, but Georgette Heyer was one of them. Despite its swashbuckling element, in may ways The Black Moth is a surprisingly mature work. The portrayal of Jack’s brother, Richard, for whom Jack has given up everything, is insightful and says much about the youthful Georgette’s ability to understand people. She depicts Dick’s burden of guilt, his moods of depression and his encounters with his temptestuous wife (the woman for whom he has sacrificed his honour) with genuine perception and empathy. Most seventeen-year-olds are preoccupied with their own feelings and situations to bother observing the people around them, but the adolescent Georgette had already developed a degree of perception and an understanding of human nature that must be considered unusual in one so young. Even if she was drawing on her own experience or taking inspiration from the people she knew, to be able to create such well-realised characters and portray their difficult relationship as effectively as she did at just seventeen was a remarkable achievement.

My father thought well of it, and insisted that I should do some serious work on it, with publication in view. I did, and it found a publisher in Constable’s – first crack out of the bag!

Georgette Heyer, letter to her publisher, 1962

“First crack out of the bag”

Encouraged by her literary father, Georgette submitted her first novel to the London publisher, Constable, for their consideration and a few months after her eighteenth birthday, they made her an offer. Constable offered her a contract with a £100 advance for the British and American rights to The Black Moth. It must have been a thrilling experience to have her work accepted ‘first crack out of the bag’ and it would not have been surprising if Georgette had leaped at the offer and signed the contract without further consideration. But she was not without some experience of the publishing world, albeit vicariously. Her father, George Heyer, was himself a minor author with poems and essays published in Granta, The Pall Mall Gazette, The Athenaeum, The Saturday Westminster Review and Punch. He also had theatrical connections through his work for King’s College Hospital and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Committee. Georgette had listened and learned from his experiences. and so, before she signed the contract with Constable, she sought professional advice.

The 1929 Heinemann jacket – the original Constable jacket remains a mystery but may have had a similar design.

The 1929 Heinemann jacket – the original Constable jacket remains a mystery but may have had a similar design. Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, reported that Georgette’s photo appeared in a medallion on the back cover. Was it this photo?Written when she was only seventeen, The Black Moth was to be the first of Georgette Heyer’s wildly popular novels.

Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, reported that Georgette’s photo appeared in a medallion on the back cover. Was it this photo?Written when she was only seventeen, The Black Moth was to be the first of Georgette Heyer’s wildly popular novels.The Society of Authors

On 28 March 1921 Georgette wrote to the Society of Authors:

Dear Sir

Herewith the contract of which I wrote. I should be very glad if you would give it your attention – especially clause 17.

Yours truly

Georgette Heyer

Society of Authors Archive (1876-1982), British Library

Established in 1884, the Society existed specifically to protect the rights of authors and assist them with advice regarding agents, publishers and contracts. The Secretary of the Society was a solicitor and members could receive legal advice from the Society’s committee and solicitors without cost. Georgette’s earliest known letter extant was written to the Society. Three days later she received a comprehensive reply in which her correspondent raised a number of issues relating to several of the contract clauses.

Her First Contract

It is impossible to know the precise contents of Georgette’s first contract as the document was destroyed along with the rest of Constable’s archives in the bombing raids on London during the Second World War. Some sense of The Black Moth contract clauses is apparent, however, both from the Society’s letter and from Georgette’s prompt and decisive reply. Despite her young age, her letter is impressive, not only for its clear-headed grasp of her correspondent’s detailed advice, but also for her insight into her publisher’s position:

Thank you very much for the advice on my contract. On most points I agree with you, but Clause 3 – concerning the American sales, I am leaving as it stands. Houghton Mifflin are collaborating with Constable’s, and publishing my book in America. The profits of net sale are to be divided equally between Constable’s and myself. As Constable’s run a certain amount of risk in bringing out an entirely new author, I think this is generous.

Georgette Heyer to the Society of Authors 1 April 1921, Society of Authors Archive (1876-1982), British Library

The 1965 Pan edition

The 1965 Pan edition The 2004 Arrow edtionGeorgette Heyer’s debut novel has been published in many editions since its first publication in September1921.

The 2004 Arrow edtionGeorgette Heyer’s debut novel has been published in many editions since its first publication in September1921. Even at 18 Georgette had an unusual degree of confidence in her writing and in her literary future:

‘As to Clause 17 – concerning my future three books, I intend to ask that in the event of my second book reaching 10,000 sale, when I shall receive 20% on it, my third book shall start at that percentage’.

In the end she decided that her request for a higher royalty for her third book “was too much to ask, and I didn’t ask it!” In the spring of 1921 Georgette Heyer signed her first book contract and set her feet upon the path that would in years to come would see her recognised as one of the world’s bestselling authors.

The Black Moth was published in September 1921, one month after her nineteenth birthday. Almost one hundred years later, it is still selling.

A delightful addition to Georgette Heyer’s debut novel, Reading Heyer: The Black Moth is offers readers a modern-day take on this classic historical romance. Perfect for the twenty-first century first-time reader as well as the diehard fan looking for further insight into Heyer’s famous novel, Reading Heyer: The Black Moth is wonderfully entertaining.

March 30, 2020

Perfect Pandemic Reading: Introducing Georgette Heyer

A bad week was a “three-Heyer” week – a week where reading three Heyer novels was the perfect panacea for whatever challenges life had thrown at them. I loved this idea and it reminded me of why I love reading – and re-reading – Georgette Heyer.

Georgette Heyer’s witty, clever novels make perfect reading in times of illness or stress – a great escape.

Georgette Heyer’s witty, clever novels make perfect reading in times of illness or stress – a great escape.Read and loved for 100 years

There aren’t many writers whose works live on after their

death, but Georgette Heyer is one of them. She wrote across several different

genres but her forte was historical fiction. Today, Georgette Heyer is credited

with having created the ‘Regency’ genre and twenty-six of her delicious novels

are set in that colorful, compelling period when men (like Mr Darcy) wore

wonderful clothes and drove elegant carriages, women were raised with marriage

as their primary goal and were ‘on the shelf’ at twenty, and manners and etiquette

were of vital importance to the upper class.

Born in 1902, the young Heyer had the benefit of her

father’s Classical education and love of books. She was brought up on a rich

diet of Shakespeare, Austen, Dickens, Kipling and several centuries of great

poetry. She was a voracious reader and began making up her own stories in early

childhood. When she was seventeen she wrote her first novel, The Black Moth. It was published in

1921, one month after her nineteenth birthday. Nearly one hundred years later, The Black Moth, along with fifty of

Heyer’s other novels, is still in print. An enduring bestseller, she has sold

in excess of thirty million books and is now being read by a fifth generation

of enthusiastic readers.

Heyer’s first novel is still loved by readers 100 years after its first publication.

Heyer’s first novel is still loved by readers 100 years after its first publication.“The language is so alive, so comic.”

There is something compelling about a writer who can

transport her reader into another time and place; into a world so convincing

that you cannot help but see it as though you were really there; and with

characters who leap off the page as living, breathing people. Heyer’s settings

feel real, her plots are ingenious and her dialogue sparkles. Even when her

vocabulary is unfamiliar, such is the power of her pen that you still get the

gist of it. In her Regency novels, in particular, there are so many new (although

they are authentically old) and wonderful words to intrigue and delight her

readers: words like ‘bosky’ and ‘cutpurse’, ‘dudgeon’, ‘ames-ace’,

‘slibber-slabber’ and ‘faradiddle’. As well-known actor and author, Stephen

Fry, has said, ‘It’s her language I think that admirers of Georgette Heyer

relish the most. It’s true there’s something quite extraordinary about it. It’s

all authentic. The language is so alive, so comic.’

Actor, author and comedian, Stephen Fry loves Georgette Heyer’s novels and revels in her language and dialogue. Stephen Fry unveiled her English Heritage Blue Plaque in June 2015.

Actor, author and comedian, Stephen Fry loves Georgette Heyer’s novels and revels in her language and dialogue. Stephen Fry unveiled her English Heritage Blue Plaque in June 2015.Laugh-out-loud comedy

Georgette Heyer excelled at comedy – especially ironic

comedy. She knew how to invert a scene, how to upend and explode reader

expectations, and her language has an almost theatrical timing. She picks up

her readers and carries them along through her complex and deftly-woven plots

all the way to her masterfully-written imbroglio endings. It is Heyer’s

characters who remain with the reader long after the last page is turned.

Though drawn mainly from the upper echelons of Regency society, her all-too

human creations stride, mince, ride, waltz and fumble their way through her

impeccably-researched fictional world.

Heyer could bring a character to life in a sentence and she

delighted in creating individuals whose flaws and foibles reflected her keen

eye for human nature. She depicted the pompous, the vulgar and the smug, humorously

wielding her pen like a sword to cut them down to size. She brought to life

naïve women and rakish men, clever women and stupid men, downtrodden and

dependent women and their domineering lords and gave them believable stories of

transformation and redemption. And she did it with a dry wit and a sense of

humour that still makes her readers laugh out loud.

The Unknown Ajax is one of Georgette Heyer’s brilliant ironic comedies.

The Unknown Ajax is one of Georgette Heyer’s brilliant ironic comedies.So much to look forward to…

For those lucky enough to know her novels – and her Regency

and Georgian novels, in particular – just the mention of a character’s name is

enough to provoke a smile or a laugh. She had a genius for creating comic

characters, among them Sir Bonamy Ripple, the indulgent gourmand in False Colours, Ferdy and Nemesis in Friday’s Child, Claude and his valet,

Polyphant, in The Unknown Ajax,