Jennifer Kloester's Blog, page 4

June 18, 2021

The Toll-Gate – A ripping yarn! Part 1

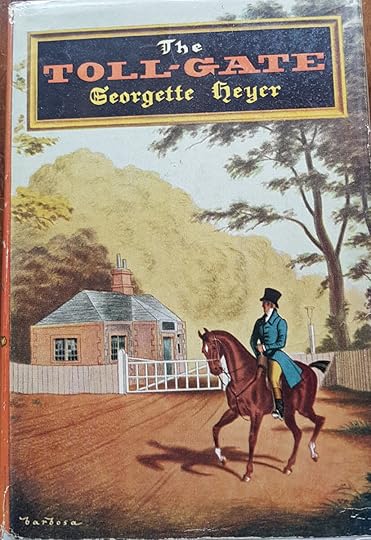

The 1954 Heinemann first edition jacket for The Toll-Gate, designed by Arthur Barbosa. It would be the first of his 15 Heyer jackets. Inspired by limestone caves

The 1954 Heinemann first edition jacket for The Toll-Gate, designed by Arthur Barbosa. It would be the first of his 15 Heyer jackets. Inspired by limestone cavesIn the summer of 1953, Georgette Heyer visited the famous limestone caves of Derbyshire. She was on holiday, possibly heading north to Greywalls in Scotland, and was intrigued by the magnificent caves of the Peak District in Derbyshire. The most famous of these is the Peak Cavern, also known, since the sixteenth century, as the “Devil’s Arse”. Today, only two main caverns are open to the public, but in Heyer’s day, she was able to visit the “Devil’s Staircase”, “Halfway House”, to see the river known as the “inner Styx” and to cross the wooden bridges known as the “Five Arches”. It was her visit to the Peak Cavern that gave her the idea for a book set in Derbyshire. What follows is the complete letter that Georgette Heyer wrote to her publisher just a couple of months after returning from holiday. It is rare for Heyer readers to gain a detailed insight into how she actually wrote her novels; how much plotting she did and how well she knew her characters before putting pen to paper. Heyer was notoriously private. She resisted talking about her books and her son once told me that she couldn’t have told you how she wrote (and she would have hated the question too!) only that it came naturally and that once she had begun it usually happened quickly.

A visit to Derbyshire’s limestone caves inspired Georgette Heyer to include them in The Toll-Gate.

A visit to Derbyshire’s limestone caves inspired Georgette Heyer to include them in The Toll-Gate. Photo Peter Barr, Wikimedia Commons.A letter and an outline

In October 1953, Georgette Heyer penned a letter to Louisa Callender at Heinemann. Miss Callender had written to ask if Georgette could give her an outline of her next book so that Louisa might tell Miss Sutherland, the editor of Woman’s Journal to expect a new Heyer for serialisation in her magazine. One of the fascinating things about Georgette’s letter is seeing the ways in which her original plot both holds to and deviates from the final book.

Dear Louisa,

Are you trying to be funny? Tell you about my new book indeed! How can I, when I haven’t yet worked it out for my own information? The title will be The Toll-Gate. That, at least, is certain. It is Regency – just after Waterloo. The hero is a huge young man who has sold out of some dreary cavalry regiment or other because he doesn’t fancy the army in peace-time. His name is John, and I’m not entirely sure of his surname, but think it may be Rivington. He is either a Major or a Captain, and he has a reputation for doing crazy things, and liking Adventure. He is fair, and (of course) handsome, and not very Heyer-hero, because definitely nice. I can’t tell you his regiment because I haven’t yet looked up the Peninsular cavalry. I rather think the Household Troops didn’t come on the scene in Spain until too late for my hero, so he was probably in the dragoons.

Heyer’s new hero was to be a cavalry officer who fought in the Peninsular Wars and at Waterloo.“a general air of Fear and Mystery”

Heyer’s new hero was to be a cavalry officer who fought in the Peninsular Wars and at Waterloo.“a general air of Fear and Mystery”Well, this character, riding alone at dusk – probably on his way to stay with a friend – comes to a toll-gate and can’t get the gate-keeper to show himself. Finds this person in extremis, distressed wife in attendance, and takes over his duties for the rest of the night. [now, whether he did this out of kindness, or because the gate-keeper had been Done to Death – which I think happened – and there’s a general air of Fear and Mystery, which naturally intrigues our gallant Captain – or Major – I can’t tell you; but I incline to think the latter was the way it was.] Next morning, bright and early, he has to go out (unshaved) to open the gate to none other than Our Heroine, Nell Stornaway. This damsel is an outsize, which made her very unsuccessful during her one and only Season in London; she lives with semi-paralysed grandfather in adjacent and mouldering mansion, and runs things, which makes her a bit masterful. Grandpa has played ducks and drakes with his fortune, the estate is entailed, and he’s a baronet. Heir is Horrid Cousin, Henry Stornaway, who, for reasons which appear inexplicable, has elected to park himself in the Mouldering Mansion, with a Gross Crony, Nathaniel Coate, who is enamoured of Nell.

Heyer would have seen some of the few remaining toll-houses on her travels.“Struck all of a heap”

Heyer would have seen some of the few remaining toll-houses on her travels.“Struck all of a heap”Well! – Our Hero is struck all of a heap by Nell, and instantly decides to go on Keeping the gate. And all sorts of things happen – though exactly what I don’t know. I rather think Henry Stornaway is carrying on some highly improper and illegal business, but what it was I’m damned if I can discover. I rather want to bring in a Bow Street Runner (Gabriel Stogumber); but if the business was smuggling in a big way, I think it would have to be an Excise Officer, which isn’t so good. Obviously the gatekeeper was working for him, and fell out with him. Furthermore, Our Hero, little though he knows it, has succeeded to his cousin’s Earldom, said cousin having had an accident – either out cubbing, or fell down a flight of stairs. Practically on the eve of his marriage. Another cousin, [~~~~ for the life of me I cannot decipher this word! If you can help, please see the photo below.], having discovered where Our Hero is lurking, tries to do him in. And, Grandpa, feeling his End at Hand, and having nothing to leave Nell, and being afraid of what may happen to her at the hands of Henry and Nat Coate, asks Our Hero if he’s willing to marry her, which, of course, he is, and that provides this fertile author with heavenly wedding-scene by candlelight and special licence, at Grandpa’s bedside. Naturally, Our Hero has divulged his identity, so this isn’t as cock-eyed as it sounds. I think Evil Cousin has to be exposed, and no doubt there are all sorts of adventures during the course of this entrancing narrative. There is (of course) a nice dandy, called Wilfred Babbacombe, who is a friend of Our Hero’s, and gets pressed into the service to mind the gate while O.H. was waltzing off on affairs of his own. [This provides Our Author with material for Comic Scene, Wilfred, all pansied up, trying to exact toll from cowherd driving cattle to be milked. Such were exempt from toll-duties.]

A section of Georgette Heyer’s outline for The Toll-Gate with the word I cannot decipher circled in pencil.“It’ll make a splendid serial”

A section of Georgette Heyer’s outline for The Toll-Gate with the word I cannot decipher circled in pencil.“It’ll make a splendid serial”Can you do anything with that? For God’s sake, don’t commit me to anything except mammoth hero and heroine and the toll-gate! It may sound a bit nebulous to you, and I admit that there are lots of loose-ends, but it’ll work out in the end. And warn the S.B. that it’s on the way, so that she can keep space. Once I’ve settled the plot it won’t take me more than two months to write, It’ll make a splendid serial, so don’t let’s listen to any backchat from that afflictive woman. If we tell her now that I’m doing it, she’ll have no excuse for putting off serialisation for months and months.

Ever, Georgette

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 7 October 1953.

Georgette was pleased with her “mammoth” hero and her “oversized” heroine – who at 5’9″ was an inch shorter than her creator!“I’ve got it pretty well taped now”

Georgette was pleased with her “mammoth” hero and her “oversized” heroine – who at 5’9″ was an inch shorter than her creator!“I’ve got it pretty well taped now”

Dear Louisa

I think I’ve got it pretty well taped now, thanks in some measure to my Life’s Partner who suddenly uttered the cryptic word [“specie!”] I never did much like the idea of smuggling, and I began to think the Bad Man might have got away with bullion, which they hid in a limestone cave in Derbyshire. (I am determined to use these caves, which I saw two months ago!) Ronald didn’t go very big for the bullion notion, foreseeing snags. But having a pachydermaton’s memory he recalled, out of the blue, that I once read him a long spiel about coinage after Waterloo, when. For the first time in years, we issued new gold and silver coins, and – which is important – minted the first sovereigns and half-sovereigns, calling in the guineas. So what could be better? Specie was being sent north – to Scotland, unless I find the Scots minted their own – and the wagon-load was snatched. But since the new money was of course “hot”, it had to be kept until a lot was in circulation. What better place than an unknown cave? What’s more, we won’t have the gate-keeper in extremis: we won’t find him at all. Not until later, when Our Hero finds his body in the cave. [The cave I went through was like a refrigerator, and I thought at the time it would come in handy for a corpse!] So there we are – but of course all this stuff isn’t immediately disclosed. You can just say it’s an adventurous romance.

The new coinage – the two sides of the King George III half sovereigns newly-minted in 1817. Photo: Roger Climpson Wimkimedia Commons“This is just what the doctor ordered for the fans.”

The new coinage – the two sides of the King George III half sovereigns newly-minted in 1817. Photo: Roger Climpson Wimkimedia Commons“This is just what the doctor ordered for the fans.”Oh, the hero is Captain John Staple, late of the 3rd Dragoon Guards. I’ve got a cast of upwards of 30 persons, but the main protagonists are Staple, Nell Stornaway, Jeremy Chirk, highwayman, Gabriel Stogumber, Bow Street Runner, masquerading as bagman, and Rose Durfield, maid to Nell, and being courted by my heavenly highwayman. Unless I miss my bet, he’s going to steal the book. I hope that gives your travellers enough to go on. If you’re going to write a preliminary puff, do leave it vague! I’ve decided I can’t open with the arrival at the deserted toll-gate. I shall have to plump into the middle of a Staple family gathering – party in honour of Earl of Saltash’s engagement to a dim type. If I don’t do this, and bring on Lucius Staple, the Captain’s jovial but wicked cousin, I shall make it difficult for myself later on. Really, the more I consider the matter, the more convinced I become that the S.B. can think herself lucky. This is just what the doctor ordered for the fans.

Ever Georgette

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 12 October 1953.

Captain John Staple was an officer in the 3rd Dragoon Guards and fought at Waterloo.Part 2 of The Toll-Gate next week…

Captain John Staple was an officer in the 3rd Dragoon Guards and fought at Waterloo.Part 2 of The Toll-Gate next week…

June 11, 2021

Detection Unlimited – the last detective novel

The 1953 Heinemann first edition jacket with illustration by Stein.

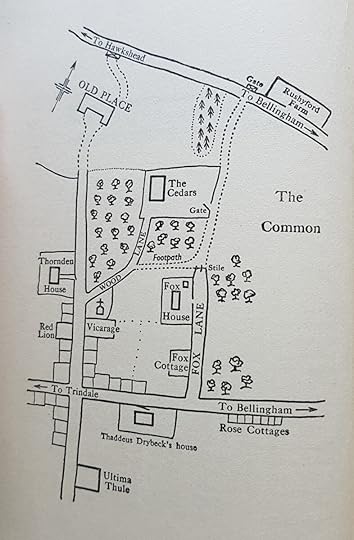

The 1953 Heinemann first edition jacket with illustration by Stein. Georgette’s map of Thornden, her fictional village in the novelGeorgette’s dedication read: “To all such persons as may imagine that they recognise themselves in it, with the author’s assurance that they are mistaken““I might bend my reluctant mind thrillerwards”

Georgette’s map of Thornden, her fictional village in the novelGeorgette’s dedication read: “To all such persons as may imagine that they recognise themselves in it, with the author’s assurance that they are mistaken““I might bend my reluctant mind thrillerwards”In April 1952, while she was writing the last pages of Cotillion, Georgette commented that her publisher, A.S. Frere of Heinemann, had blithely informed her “that he has scheduled a detective novel by Me for this autumn. Why he doesn’t write Humorous Books instead of publishing tripe by Bevan I shall never know. He appears to me to be a Master of the Improbable.” [Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 29 April 1952.] In May, Georgette finally sent Cotillion to her publisher at Heinemann. Though she declared the manuscript “the messiest MS I have yet sent you,” she was pleased with the book, which had proven to be one of her longer novels (it was 112,000 words). She told Frere that “it seems to me to run easily; and I do think it has its moments – not to mention my own favourite hero” – a sentiment about the delightful Freddy Standen that would be shared by many of her fans for generations to come. To celebrate the completion of the new book, Frere took her to lunch – most probably to the Ritz or the Savoy as both were favourite eating spots with excellent wine lists! A few days later Georgette wrote to say:

‘Many thanks for a lovely lunch, which I enjoyed more than somewhat. It did me a great deal of good, and I came straight home and wrote a short story. I am now going to write another, called Pink Domino; and if I can think of the plot of it, I shall do a third, called Cold Dawn. After that, I might bend my reluctant mind thrillerwards.’

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 5 May 1952.

In 1952, Georgette wrote several short stories, in part to pay for her brother Boris’s wedding reception. “Bath Miss” appeared in Good Housekeeping.Short stories and a wedding

In 1952, Georgette wrote several short stories, in part to pay for her brother Boris’s wedding reception. “Bath Miss” appeared in Good Housekeeping.Short stories and a weddingThe short stories were a necessary distraction from the planned new detective novel because Georgette’s brother Boris, five years her junior, had “announced his intention of getting married” and Georgette had generously offered to pay for his wedding reception. Her status as a consistent bestseller and the increasing demand from readers for her historical novels meant that her short stories were also in demand. Magazines were still hugely popular in the 1950s and famous authors were well-paid for their short stories. Georgette was no exception. Her agent, Joyce Weiner, easily sold “Pink Domino” to Woman’s Journal and “Bath Miss” to Good Housekeeping for £200 each. “Cold Dawn” very likely became “The Duel” which was published in Good Housekeeping early the following year. It was good money for a few hours work and Boris’s wedding to Evelyn Lyford, a “charming widow”, was a great success. The reception took place at Albany with Georgette and Ronald playing host to the wedding guests. It was a delightful celebration and marked the beginning of a happy marriage. Georgette’s other brother, Frank, would also marry a widow, but neither of the Heyer men would have children and the family name of “Heyer” – which their sister would make internationally famous – would eventually die with them.

Boris Heyer married his “charming widow”, Evelyn Lyford, on 10 July 1952.“Rather an honour”

Boris Heyer married his “charming widow”, Evelyn Lyford, on 10 July 1952.“Rather an honour”With the wedding behind her, Georgette told friends that she “’hoped to rush off Detection Unlimited”, but a welcome distraction in the form of a special commission again prevented her from starting the new detective novel. King George VI had died in February 1952 and his daughter, Elizabeth, was to be crowned in June 1953. In July 1952 the editor of Good Housekeeping asked Georgette to write a brand new Regency short story for their special Coronation edition. Such a special request could not be ignored and Georgette told Frere that she had been given free rein to write

“what I like, as long as I like, at Joyce’s price, and not theirs. I thought I ought to make an effort to do this, for I suppose it is rather an honour. And so far I haven’t an idea in my head. Lord, why didn’t I take up charring, or something easy?”

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 10 July 1952.

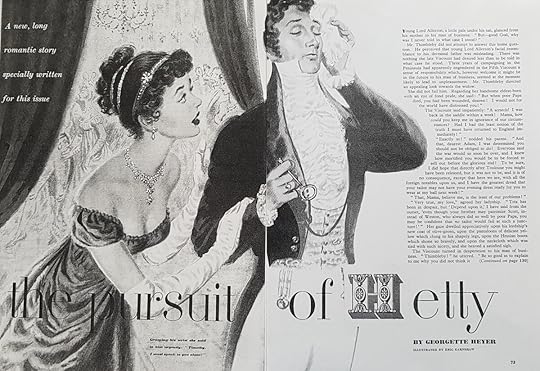

Despite her worry that she would find writing this special story it a challenge, in typical Heyer style, Georgette soon produced a charming tale of almost-thwarted love, which she called “The Pursuit of Hetty”. It was a delightful tale, and in years to come, elements of the story would form the basis of two of her Regency novels.

The front cover of the special Coronation edition of Good Housekeeping which featured Georgette Heyer’s short story, “The Pursuit of Hetty”.

The front cover of the special Coronation edition of Good Housekeeping which featured Georgette Heyer’s short story, “The Pursuit of Hetty”. Georgette’s short story written especially for the Coronation edition of Good Housekeeping.“I must write a thriller”

Georgette’s short story written especially for the Coronation edition of Good Housekeeping.“I must write a thriller”Unusually for a Heyer novel, and despite Heinemann’s enthusiasm for the novel, the timeline for writing Detection Unlimited is unclear. In the letters extant for the second half of 1952, Georgette does not mention the manuscript. It is not until February 1953, in a letter to Frere, that she finaly mentions the long overdue book again: “I must write a thriller, & I want to get on with my medieval chronicle. I have been deep in Medieval Industries lately, & fascinating they are.” She must have put the medieval research to one side, however, for she finally began Detection Unlimited shortly afterwards and had finished it by June 1953. Heinemann immediately sent the manuscript to Dorothy Sutherland, the editor of Woman’s Journal. Georgette had every expectation that Miss Sutherland would buy the novel and make it the magazine’s next serial story. Unfortunately, in mid-July, Georgette received a letter from Louisa Callender at Heinemann to say: “I have heard from Miss Sutherland this morning. She says: ‘I am afraid DETECTION UNLIMITED just isn’t serial material.’ Isn’t it disappointing? I did not expect this. I am now trying elsewhere with it.” Sadly for Georgette, by September the message was clear – magazine editors could not see the novel as serial material and Georgette wrote at the bottom of one of the Heinemann letters: “”Nobody has taken “Detection Unlimited” for serial. They all say it won’t serialise!” It was a decided blow as she had been counting on the money from the serial to pay a large tax bill.

I can’t say I’m surprised, though I am cast down! I only wrote the thing for sordid gain, so I hope to god you manage to get rid of it. I shall be home on Monday – and it seems to me that if Detection Unlimited won’t serialize I shall have to knock off another blasted romance, purely for that purpose.

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 16 July 1953.

The 1956 Pan paperback edition.A clever character study

The 1956 Pan paperback edition.A clever character studyThe crack about writing only “for sordid gain” wasn’t true, for Georgette had actually put a lot of thought into the book. Detection Unlimited is among her best detective novels, in part because it is not only very witty but also a really clever character study. It is a Chief-Inspector Hemingway novel and the detective’s famous love of psychology and his conviction that the more complicated things become the closer he is to solving the murder are very much to the fore. One of the fascinating things about the book is its many descriptions of life in 1950’s England. The mention of such things as “Lincrusta Walton” wallpaper, the radio program: Mrs Dale’s Diary, and the vivid description of The Sun, the hostelry where Hemingway stays while investigating the case, are among the many vivid examples of life in a well-to-do English village in that era. Georgette’s observations about the many social changes since the end of the Second World War are also interesting. She’s noticing that “People aren’t as hide-bound as they used to be” and, while she mourns the loss of some aspects of the old social order, Georgette also recognises some of the changes as progress. It’s worth reading Detection Unlimited just to better understand her attitudes and ideas.

The original blurb for Detection Unlimited.“You might let me know…”

The original blurb for Detection Unlimited.“You might let me know…”It is unfortunate that once again her publisher seems not to have read her novel either in manuscript or in its final book form, In August, Georgette wrote to Frere to say:

You might let me know some time or other whether you like, dislike, or tolerate the book. I think you’ll appreciate the first appearance on the scene of Mr Haswell: the passage between him and his son went right home, when read by Mr G.R. and Mr R.G. Rougier. Richard said thoughtfully: A boy’s best friend is his mother – they say!

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 21 August 1953.

It must have been incredibly frustrating for Georgette, who, despite comments about having written only for “sordid gain” or having to write “another blasted romance”, so clearly cared about her novels and wanted her publishers to care too. For much of her writing life she longed for feedback from people in the industry whom she admired and trusted to be honest with her. Too often she was disappointed. Detection Unlimited was to be her last collaboration with Ronald. He provided her with the obscure but vital legal key to the mystery by coming up with a “Cestui que trust” – a thing that almost no one has ever heard of but which in trust law is “is the person or persons who are entitled to the benefit of any trust arrangement.” They had enjoyed their many collaborations, especially in the early years when he had helped Georgette with the research for books like Beauvallet and The Conqueror. Ronald had devised some devious murder methods, but he was now busy with his law practice and Georgette had written her last murder mystery. From now on she would write only Regency novels and work on the medieval story she had so long wanted to write.

The 1969 Dutton hardback edition

The 1969 Dutton hardback edition The 1971 Bantam paperback editionThe “Ultimas” – pure-bred Pekingese

The 1971 Bantam paperback editionThe “Ultimas” – pure-bred PekingeseIt is impossible to write about Detection Unlimited and not mention the dogs. Georgette loved dogs and featured some marvellous canines in several of her novels. In this last of her mysteries she had a lot of fun with the “Ultimas” – the pomp of pure bred Pekingese dogs owned by the delightful Mrs Midgeholme. Having named her house “Ultima Thule”, Mrs Midgeholme’s breeder name for her “Peekies” is “Ultima” and each new dog’s personal name begins with the letter “U”. This leads to some very funny passages where various characters in the novel talk about the dogs’ unusual names. As these include Ultima Urf, Ultima Untidy, Ultima Ullapool, Uppish, Ursula, Umbrella, Uplift, Unready, Urbania,, Ulrica, Uriah, and Ultima Umberto, there is plenty of scope for comedy: “Not bad, really, except that one would feel such a fool, shouting Urf, Urf, Urf, in the street.” And when a new litter is born there are hilarious suggestions of Ultima Uzziah, Umslopogias [from Rider Haggard’s Alan Quartermain novels], and Ullulume. Mrs Midgeholme, as their doting owner, generally refers to her dogs as her darlings, her treasure, and angel, and kisses them whenever she is sure their feelings have been hurt. In Detection Unlimited, one suspects that, having had at least one Pekingese in the family of her youth, Georgette was remembering the ways in which one or more of her female relatives spoke to their pet.

Mr Drybeck, wincing at his companion’s frequent shrieks to Umbrella, Umberto and Uppish, was forced to remind himself, not for the first time, that Flora Midgeholme was a good-natured and plucky woman, who bore uncomplainingly the hardships of a straitened income, eked it out by dispensing with the services of a maid and by breeding dogs, and always presented to the world the front of a woman well-satisfied with her lot.”

Georgette Heyer, Detection Unlimited, Pan

Georgette was familiar with the Pekingese breed of dog she describes in Detection Unlimited.“In the best of humour”

Georgette was familiar with the Pekingese breed of dog she describes in Detection Unlimited.“In the best of humour”“Miss Georgette Heyer practises a very much milder mystery that Mr Chandler [Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye], and the murder of an objectionable solicitor in Detection Unlimited is solved without recourse to violence and in the best of humour. Chief Inspector Hemingway and Inspector Harbottle are summoned from Scotland Yard to make the acquaintance of a variety of local characters, most of whom are busy with amateur solutions of the crime, though they can legitimately be regarded as suspects. Miss Heyer writes with ease and manages her plot with quiet efficiency, setting no store by sadism or painful suspense, taking more pleasure in the social comedy of the residents who are excited by the case than in the darker aspect of the hunt for the killer. “It sounds like a nice case,” remarks Chief Inspector Hemingway, when confronted with it, and it is a nice case, making no demands whatever on the nerves.”

The Times Literary Supplement, 1 January 1954.

June 4, 2021

“Georgette Heyer – The Shy Bestseller” by Coral Craig

In 1952, an Australian journalist, Coral Craig, contacted Georgette Heyer’s publisher to request an interview. Ms Craig had been a journalist at Consolidated Press since 1935 and in 1943 had been granted accreditation as an Australian War Correspondent. Living in London in the 1950s she wrote for the Australian Woman’s Day magazine and covered the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953. A longtime fan of Georgette Heyer, Ms Craig had formed her own ideas about one of her favourite writers and so she was startled to discover that, unlike most other authors, Miss Heyer did not give interviews. For some reason – as yet unknown – Georgette invited Ms Craig to visit her at home at Albany on the strict condition that they not talk about her books or writing. The following is the article published in Woman’s Day on 27 October 1952. The quoted parts in bold are the original article with additional information from me in square brackets.

Coral Craig

Coral Craig Photo used with permission.“From Miss Coral Craig of our London Office” – Australian Woman’s Day

“Charming Hostess”

Miss Georgette Heyer, whose delightful Cotillion begins in Woman’s Day next week is undoubtedly one of the most widely read authors in the world. She is also perhaps the most publicity shy; certainly the shyest of personal publicity I have met.

In the highly competitive book world it usually needs only a telephone call to the publisher of a new novel to get plenty of biographical material and a kindly photograph of the author. Miss Heyer’s publishers, Heinemann’s, responded: “Sorry, there are no pictures of Miss Heyer. She dislikes personal publicity. We can tell you she has published 20 or so historical novels and detective stories [Cotillion would actually be her 39th novel] and, of course, we’ll pass on the message that Australians are interested in her, but she is never, never interviewed.” [Georgette seemed to have a soft spot for Australians who had loved her novels from the first, and she was very kind to her young Australian correspondent, Rosemary Marriott, to whom, in 1952, she was still sending her annual chatty letter along with a signed copy of her latest book.]

She is probably about 90 and unphotogenic, I reflected a little sourly, adding up how many moons had come and gone since I had fallen in love with the hero from “These Old Shades”. [An Australian librarian wrote to Heyer after “These Old Shades” was published there to tell her that she was “A bonzer woman” and that “‘all the girls who read the filthiest books like yours!”]

My hazy mental picture of Georgette Heyer, which I find not unlike the picture many of her readers cherish for want of more precise data, was of a frail, silver-haired old lady living in a Regency mansion amid the atmosphere of elegance she writes about. Tucked away, of course, in a remote, lavender-scented hamlet, probably scorning new-fangled motor cars and travelling only by coach-an-four. [Georgette had certainly lived in a hamlet in Sussex in the 1930s, but it was more likely to have been tobacco-scented than lavender! Needless to say, Georgette found this fantasy of her and her life hilarious!]

Pray, imagine my surprise (as one of Miss Heyer’s characters would say) when I was asked to her flat – for a drink. [Georgette enjoyed a drink, though her daughter-in-law, Susie, has explained that whiskey was generally her first preference; probably not what you’d offer your guest in the afternoon, however.]

She lives in the very heart of London (within 100 yards of Piccadilly Circus) and is a tall, dark-haired distinguished woman, a charming hostess, who mixes an excellent dry martini, wife of a well-known Scottish-born barrister [Ronald was actually born in Odessa but he did have some Scottish forebears] and has a 21-year-old son at Cambridge. [Richard was up at Pembroke] She was smartly dressed in navy and white and the only suggestion of the 18th century was in a few fine prints on the walls. [Georgette always took great pride in her appearance. The prints are still in the family]

Her age–no secret since it’s published in Who’s Who–is 49, and she looks scarcely that. She was only 17 when she began writing and has now forgotten exactly how many books have been published. One or two she prefers to forget entirely. [Those she had suppressed by this date include her four contemporary novels, along with “The Great Roxhythe” and “Simon the Coldheart”]

Miss Heyer’s publishers were right. She isn’t interviewed. She made it quite clear, with a subtlety conveyed neither by word nor gesture that this was a social occasion and no questions, please, about Georgette Heyer, author. [This was typical of Georgette, who deemed vulgarity the one unforgiveable sin. She would have thought it very vulgar to talk positively about her work – especially to someone who admired it] As the name on her old, polished wood door said, she was simply Mrs G.R. Rougier. [She always enjoyed the anonymity given her by her married name.]

As such, my hostess tossed the conversational gambits back and forth across the centuries, discussing in a most definite manner any subject except her own work. She talked of The Albany [for my blog about Albany, click the link] where she lives with her husband and son. It is one of London’s most splendid buildings which, in grander days, 1770, was built as a town mansion for Lord Melbourne. Marble wall plaques bear witness that Gladstone, Lord Macaulay [whose ghost was said to haunt the Rougier’s apartment, F.3. Georgette appreciated the ghost but always said it never troubled her.] and Byron are among the famous who have resided there since it was converted to apartments.

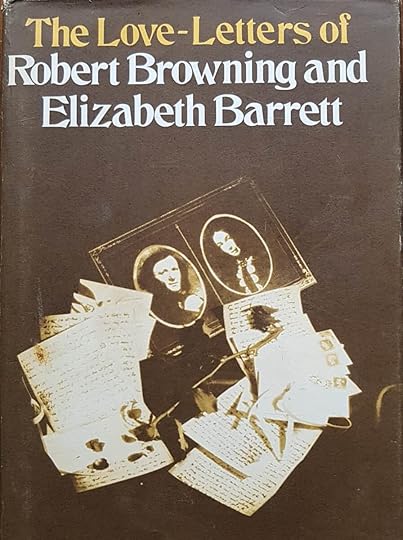

Georgette never travelled without the love letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett.“Good town address”

Georgette never travelled without the love letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett.“Good town address”

The Albany, you may remember, was also the good town address Oscar Wilde gave to his gay bachelor Jack Worthing in “The Importance of Being Earnest”. [Georgette loved Oscar Wilde’s wit, which was not unlike her own. In her own novel, “The Foundling” she gives her handsome bachelor, Gideon, an apartment in Albany.]

She spoke of poets:–Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett: “I never travel without The Browning Letters.” These are the love letters written between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett from 10 January 1845 until 18 September 1846 – a week after their marriage. Not only are they among the most romantic letters ever written and later published, they also provide important insights into the ideas, thoughts and lives of these two beloved poets. Knowing that Georgette always travelled with them reveals something of the romantic side of her nature.]

The 18th century:–“The Age of Elegance I would choose to have lived in–with the required wealth, of course.” [Here is a clue to her early books – “The Black Moth”, “Power and Patch”, “These Old Shades”, “The Masqueraders”, and “Devil’s Cub” are all 18th-century novels and each reflects Georgette’s idea of “the Age of Elegance”.]

Critics:–“I do not think that professional critics’ opinions have much, if any, effect on sales. I do not read them. Cherishing reviews of one’s own books has always appeared to me to be the ‘last infirmity of noble mind'”. [Georgette is here quoting Milton from his poem, “Lycidas” , in which Milton declares Fame as the infirmity: “Fame is the spur that the clear spirit doth raise, (That last infirmity of noble mind)”. Georgette also refers to the poem in her novel, “Cotillion” when Kitty and Olivia Broughty are confronted by the lascivious Sir Henry Gosford and he calls Kitty “the Attendant Nymph” and Olivia “fair Amaryllis”. Kitty – as well read as Georgette -is delighted to correct his misquoting of the poem.]

Films: “‘The Reluctant Widow” is the only one of my books made into a film. Jean Kent was the widow. I didn’t see it. My son went and said, ‘Don’t go, Mother. You would hate it.’ One other book was bought by Korda and never produced–which I regard as the happiest ending to any story of mine.” [In 1939, the film director, Alexander Korda, had shown interest in filming Heyer’s novel, “Royal Escape”. At the time, Georgette had real hopes that the film would come off, as Korda had enjoyed huge success with his film “Henry VIII” starring Charles Laughton. Nothing came of Korda’s interest, but despite her avowal to Coral Craig that she was happy about it, Georgette continued to hope that someone, someday, would make her books into films.]

We regard as a happy ending to this story Miss Heyer’s comment when she read this article: “I am hugely flattered by your description of me–and shall take good care it never comes under the eye of my irreverent family. I can well imagine the reactions of my brothers!” [Georgette’s younger brothers, Boris and Frank, although huge fans, often teased her about her books and writing. This was always taken in very good part by Georgette for humour and joking had been an intrinsic part of their growing up. She enjoyed the sallies and ribald humour of all the men in her family.]

Coral Craig, “Georgette Heyer – The Shy Best-Seller”, Woman’s Day, 27 October 1952.

May 28, 2021

Cotillion – a delightful dance

An outrageous scenario“So I’ve settled that one of you shall have her, and my fortune into the bargain.”

Great-Uncle Matthew Penicuik.

The miserly Mr Pencuik is guardian to the orphaned Kitty Charing and he has decided that his ward shall only inherit his fortune if she marries one of his four great-nephews. This outrageous scenario prompts four very different reactions from Kitty’s potential bridegrooms: Hugh, the rather pompous rector, is willing to marry his cousin; Dolphington, the “impoverished Irish Earl”, is reluctant but compelled by his overbearing mother to offer for Kitty; Jack, that handsome, dashing blade intends to win the fortune but refuses to be pushed into marriage; and Freddy, whose family thinks him a fool, is oblivious to his great-uncle’s plan and arrives late on the scene. Freddy is the kindest of Kitty’s likely suitors and so, when his country cousin begs him to pretend to be engaged to her so that she may escape from her penny-pinching old guardian and enjoy a month in London, Freddy reluctantly agrees. Unbeknowns to Freddy, however, Kitty has her sights set on Jack, but Heyer’s love of comic irony means that her heroine’s path to true love is anything but smooth.

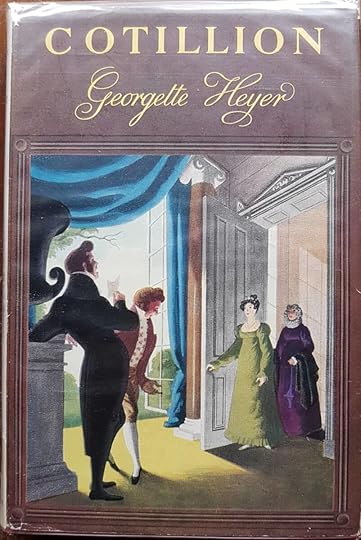

The 1953 Heinemann first edition with the jacket designed by Philip Gough. This would be his final jacket for Heyer.“Inspired”

The 1953 Heinemann first edition with the jacket designed by Philip Gough. This would be his final jacket for Heyer.“Inspired”So begins the book that would become Cotillion – one of Georgette Heyer’s most delightful novels. She began writing the book early in February 1952 and finished it three months later. It was a story she had been wanting to write for some years – ever since she had finished Friday’s Child almost ten years earlier in 1943. That novel had featured the foolish, feather-brained, but very funny, Ferdy Fakenham, one of Georgette’s favourites among her many comic characters. Many years after writing Friday’s Child Georgette told a friend that she still considered that novel: “the best I ever wrote. Perhaps because it wrote itself. Perhaps because it contains Ferdy Fakenham, who not only stole it, but inspired me, years later, to write Cotillion.” In the new novel Ferdy was originally “Felix” but “turned out to be Freddy”. Freddy is a pink of the ton, warm-hearted, genial and, at first glance, not very bright. But first glances can be misleading and Georgette took great pleasure in writing a character who would never be classified as a typical Heyer-hero. Years later she would describe these men as either “suave, well-dressed, rich, and a famous whip, according to Model No.1; or, Model No. 2, the brusque, savage sort, with a foul temper.” [GH to Max Reinhardt letter 7 April 1966] Though he is always well-dressed, Freddy is neither a Model 1 nor a Model 2, but an entirely new kind of hero. Part of the fun of the novel lies in just how long it takes for Kitty (and many readers) to realise this fact.

The first US edition of Cotillion, Putnam 1953. Freddy finds Kitty at the Blue Boar Inn.The Honourable Frederick Standen

The first US edition of Cotillion, Putnam 1953. Freddy finds Kitty at the Blue Boar Inn.The Honourable Frederick StandenThe Honourable Frederick Standen has long been a prime favourite among Heyer readers. Freddy is neither a Corinthian nor a Nonesuch, but rather a Pink of the Ton. Though fastidious about his dress, at first there seems not much to Freddy whose “countenance was unarresting, but amiable; and a certain vagueness characterized his demeanour.” It is a deliciously deceptive introduction. Freddy soon becomes involved in Kitty’s affairs and gradually a new Freddy emerges to the fascination of both the reader and Freddy’s father, Lord Legerwood. Though he appears only a few times in the novel, Lord Legerwood is one of Georgette’s most deftly created minor characters and a superb example of her skill as a writer. His encounters with his son, the way he looks and speaks, and the things he says are remarkably memorable for one with such a small part to play in the story. She throughly enjoyed writing the novel and even returned to her old habit of writng out some passages for her publisher – something she had often done in the 1930s when enthused about a new book.

my Inestimable Spouse declares it is The Real McCoy. I have certainly doubled him up once or twice, with a very choice number, called Lord Dolphington, and described by one of his cousins as “queer in his attic.” — ‘ “I ain’t clever, like you fellows, but when people say things to me once or twice I can remember them.” He observed that this simple declaration of his powers had bereft his cousin of words, and retired again, mildly pleased, into his book …

There is also a sentimental governess.– ‘ “Oh!” cried Miss Fishguard, clasping her hands over her emaciated bosom, and blushing with emotion. “Only think, Mr Frederick! – One touch to her hand, and one word in her ear, When they reached the hall-door, and the charger was near; So light to the croupe the fair lady he swung, So light to the saddle before her he sprung! And then, you know, he rode off with fair Ellen, and the lost bride of Netherby ne’er did they see! So daring in love; and so dauntless in war. Have you e’er heard the like of young Lochinvar?”

Sounds like a curst rum touch,” said Freddy disapprovingly.’

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 23 February 1952

The 1966 Pan edition.“A riot of absurdity”

The 1966 Pan edition.“A riot of absurdity”In March 1952, Georgette sent Louisa Callender an outline of the new novel. She was almost halfway through the book but obviously knew exactly what was to come in terms of the plot. She had written about 50,000 words and made sure to explain to Louisa that the synopsis did not really convey exactly what she meant to do with the plotlines. This was because she couldn’t insert explanations into the synopsis along the lines of “This sounds corny, but wait till you see how I mean to handle it!”. She had high hopes that if the novel worked out as she had planned that it would be “a riot of absurdity”.

From Quadrille to Chicken-Hazard to CotillionAt first, Georgette thought to call her new novel, Quadrille, after the eighteenth-century dance so popular during the Regency. A month later she told Louisa Callender at Heinemann that she intended calling it Chicken-Hazard – adding the tongue-in-cheek rider: “unless Frere violently objects, and quite probably even if he does, because what does he know about anything, anyway?” Both Quadrille and Cotillion are dances in which four couples perform a series of intricate steps – an apt reflection of the intricate nature of Georgette’s plot. The title, Chicken-Hazard is far less relevant to her story. Hazard is a dice game reputed to have been played by the Crusaders in the 12th century while laying siege to the Arabian Castle of Azart or Hazart. Mentioned in Chaucer, it became hugely popular in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries and when exported to America developed into the dice game known as “craps”. Chicken-Hazard refers to the same dice game only played for small stakes – hence the appellation “chicken”. Fortunately, Georgette soon thought better of the title and changed it to Cotillion.

The 1967 Pan edition.Four Couples in an intricate plot

The 1967 Pan edition.Four Couples in an intricate plotAccording to Webster’s dictionary, the Cotillion dance is “an elaborate and complicated dance … marked by the giving of favors and frequent changing of partners”. It is also a dance performed by four couples. In her novel, Cotillion, Georgette created an intricate set of movements performed by four couples. Though they are not all of them main characters, the eight players in the novel each have a vital role in the story. As in the dance, they weave in an out of each others’ lives, turning this way and that, passing from one to another, changing hands and direction until at last the dance – and the story – is done. As Georgette herself described it, “the whole thing is a sort of set-to-partners”. Kitty believes she is to partner Jack, but ends up spending more time with Freddy; simple-minded Lord Dolphington wishes to partner plain, pragmatic Hannah Plymstock; beautiful Olivia Broughty (whose mother wishes to sell her to the highest bidder), wants only to partner Kitty’s cousin, the handsome and romantic Chevalier d’Evron; and, in a neat twist at the end of the novel, Kitty’s ill-tempered, miserly guardian, Mr Penicuik, finds himself partnering Kitty’s kind and sentimental governess, Miss Fishguard. Complications abound throughout the novel but Heyer proves herself a master of the dance and achieves in Cotillion one of her cleverest and most unexpected stories. As Heyer herself explained in a synopsis for the second half of the book:

And what of Jack?It would take too long to describe the intricacies of the second half, nor should I care to be bound down to a hard and fast pattern, for at any moment a new and still more absurd situation might present itself to me. In broad outline, Dolphington, supposed by his outrageous mother to be engaged in a plot of her devising to force Kitty into marriage with himself, marries, with the maximum amount of help from Kitty, Hannah Plymstock, a plain young woman of no birth or fortune but much hard sense; Jack, with every intention of marrying Kitty in his own time, gets neither her nor the beautiful Olivia, towards whom his intentions are strictly dishonourable. Olivia, urged by her mother to marry a rich and repulsive old roué, flies to France with the Chevalier – an adventurer and a gamester, whose schemes are overset partly by his falling in love with Olivia, and partly by Freddy, whose way of getting rid of Kitty’s embarrassing cousin is unorthodox but eminently practical. Mr Penicuik upsets Jack’s calculations by deciding to marry Miss Fishguard. Freddy marries Kitty.

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, synopsis, March 1952.

And what of Jack? Little by little the contrast between Jack and Freddy becomes ever more apparent to Kitty. The Pink of the Ton comes into his own and Kitty gradually learns (as Heyer knows only too well) that Freddy would make a much better husband than handsome Jack Westruther. Georgette was often surprised by the number of her fans who wrote to her about wanting to find a man like the heroes in her novels. Georgette often observed that most Heyer heroes would make dreadful husbands and wondered at those readers who apparently swooned over them. Even so, Jack is not a intended to be a villain. As Georgette herself said in a message to Miss Sutherland, the editor at Woman’s Journal: “And don’t let her run away with the idea that Jack is a villain: there isn’t a villain.”

It is not the heroic Jack who always comes up to scratch in any impasses, but the foolish Freddy. He and Kitty grow closer and closer together until, at the end, after a grand imbroglio in Hugh’s rectory, it dawns on them that they were made for each other.’

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, March 1952.

Sir Gerald Lenanton by Walter Stoneman 1946,

Sir Gerald Lenanton by Walter Stoneman 1946, Copyright The National Portrait Gallery, used with permission“To Gerald”

Georgette finished writing Cotillion at the end of April 1952, just three months after starting it. Heinemann scheduled the novel for publication in January 1953 to allow time for it to appear in serial form in Woman’s Journal and the Australian Woman’s Day and other popular magazines. On 24 October 1952, Georgette’s great friend, Carola Oman, rang to say that her beloved husband, Gerald Lenanton, had died suddenly. He was only 56 and his death was a great blow to them all. Georgette had dedicated Cotillion to Gerald and told him that it was “his” book. He had read the book in proof while in the London Clinic only two months earlier and had greatly enjoyed it. Georgette was shattered by his death, telling Frere that “Gerald was one of the nicest people we ever knew, and we shall miss him terribly.” She also felt terrible for Carola. She and Gerald had celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary in April and were devoted to each other. Cotillion was Georgette’s small tribute to a beloved and valued friend.

Gerald Foy Ray Lenanton was still at WInchester when war broke out in 1914. amd early in the next year entered the Royal Military Academy. After receiving a commission in the Royal Artillery he saw active service with the R.H.A., rising to the rank of captain in 1918. After general demobilization he went up to Christ Church. Oxford cast its spell over him in a marked way, so that though he spent the rest of his life in business, he carried with him an atmosphere of leisure and culture which, though it made acquaintance with him a keen pleasure, yet in no way detracted from his efficiency as a business man. He had married in 1922 Carola, daughter of Sir Charles Oman, this reinforcing his ties with Oxford.

Obituary, “Sir Gerald Lenanton”, The Times, 24 October 1952.

The 2004 Arrow edition.

The 2004 Arrow edition.As she came to the end (one of her best) of her 39th novel, Georgette wrote ( a little tongue-in-cheek) to Louisa about Cotillion: “It is Terrific…It is a classic Heyer. It is EXACTLY what the Fans like. It is in my best manner.” She was right. The novel was an instant success, selling 45,000 copies in its first few months of publication.

May 14, 2021

Georgette’s lunch with the Queen

In October 1966, Georgette Heyer was in the middle of packing up her apartment in Albany, when the telephone rang. Extracting herself from the piles of books, reams of wrapping paper and the kind of chaos inevitable when moving house, she picked up the receiver. A man’s voice asked if she would speak to Sir Mark Milbank. Georgette was instantly on her guard, for her latest novel, Black Sheep, had just been published and she had been besieged by reporters calling her asking for an interview. In icy tones she said crisply, “Who is Sir Mark?” Undeterred by the frosty reception, her caller said in starchy tones: “I am speaking from Buckingham Palace”.

Sir Mark Milbank, Master of the Queen’s Household 1954-1967

Sir Mark Milbank, Master of the Queen’s Household 1954-1967 “We are all madly keen on your books here”Through the Palace gates

“We are all madly keen on your books here”Through the Palace gatesTwo weeks later, beautifully dressed, her hair elegantly coiffed, wearing gloves and with her handbag on her arm, Georgette Heyer walked down the front steps of Albany to where Ronald’s Rolls-Royce stood in the cobbled courtyard. The chauffeur, hired from Harrods, opened the door and ushered Miss Heyer into the rear passenger seat. It was not a long drive from Piccadilly to Buckingham Palace but Georgette was actually a little nervous as the car approached the Palace gates. The chauffeur, however, knew no such agitation and, revelling in the moment, greeted the policeman on duty in lofty tones. “Miss Georgette Heyer to lunch with her Majesty!” he announced. The officer bowed and stepped back, the chauffeur, visibly at bursting point, inclined his head graciously and the Rolls swept on through the Palace gates, across the courtyard to the door where a footman waited to see Miss Heyer from the car.

The gates of Buckingham Palace“A merry twinkle”

The gates of Buckingham Palace“A merry twinkle”A footman in scarlet livery led Georgette to an elegantly-appointed room where she found eleven other guests. To her great surprise, they were all men and she the only female! She was offered a sherry or a cocktail and when all were assembled, Sir Mark introduced everyone and showed them where they would each sit at table. After some desultory conversation among the guests, a courtier came in and whispered to Sir Mark that Her Majesty was on her way. He instantly marshalled the assembled company into “a serried rank” near the main doors, the footmen threw open the doors and Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phiip entered. They shook hands with everyone, Georgette accomplished a brief curtsey, and the Royal couple joined in the drinking party. Sir Mark, eager to make Georgette feel welcome, thrust her into the group around the Queen. Having been warned by her friend Carola Oman that “Royals are frightened of Inkies”, Georgette discerned a certain wariness in Her Majesty’s eye and “realized that she was scared stiff” of her literary guest: “She kept on stealing sidelong looks at me, & blushing pink whenever I happened to catch her eye”. It did not take long, however, for Miss Heyer to also discover that her Sovereign had “a merry twinkle and quite a lively sense of the ridiculous” and that her natural speaking voice was charming and not nearly so stiff and formal as the one heard on the radio.

Georgette enjoyed lunch at Buckingham Palace and was highly amused by Corgis’ arrival at the pre-lunch drinksThree Corgis

Georgette enjoyed lunch at Buckingham Palace and was highly amused by Corgis’ arrival at the pre-lunch drinksThree CorgisAfter about ten minutes of conversation, the scarlet-liveried footmen once again flung open the double doors and three Corgis rushed into the room. They hurled themselves upon the Queen, before romping about the room playing catch-as-catch-can among the guests. Her Majesty apologised for their energetic behaviour, but as a dog-lover herself, Georgette was amused to see such antics. She was even more amused to learn that the Corgis had been out that morning with the Queen’s youngest, Prince Edward, and had naturally gone into the lake which Her Majesty explained was “Filthy Muddy!” They had been bathed, of course, but Georgette thought the episode “added a cosy touch!”

The Queen was a gracious host and Georgette discerned a “merry twinkle”.

The Queen was a gracious host and Georgette discerned a “merry twinkle”. Photo by Oliver Atkins

But Georgette was a little taken aback by

But Georgette was a little taken aback by  Georgette looking elegant in the sort of outfit she might have worn to lunch with the Queen.“A certain air of unreality”

Georgette looking elegant in the sort of outfit she might have worn to lunch with the Queen.“A certain air of unreality”After lunch was over, the entire party returned to the reception room for coffee and liqueurs – though no one touched the latter. A little after half-past two, the Queen and Prince Philip bade farewell to their guests. The Queen shook hands with Georgette and said with a slight stammer, “So p–pleased! M–meeting you f–face to f–face! Goodbye!” Neither she nor Prince Philip had mentioned Georgette’s books, an omission for which she was thankful, though also a little odd, until Ronald pointed out that they had probably been advised that Miss Heyer hated taling about her novels. She had looked forward to lunch with the Queen with decidedly mixed feelings telling friends that “I’ve been to a couple of Garden Parties, but they are Different!” In the end she found it all very easy and also very funny.

There was a certain air of unreality about it, which came over me when I sat down at table. Well, I ask you, Enid! It is one thing to do a bob at a Garden Party, & quite another to find yourself chatting to Prince P., sitting almost opposite the Queen, & eating off glass plates which have the Royal Arms, in pale gold, all over their centres! I could only feel like the old woman in the nursery rhyme, “Lawks-a-mussy on me, this is none of I!” Ronald, of course, is in a state of euphoria about the whole thing, but I think it would have been more to the point if he had been invited! He does far more for the Queen than I shall ever do, & is much worthier of the honour.

Georgette Heyer to Enid Chasemore, letter, 6 November 1966

May 7, 2021

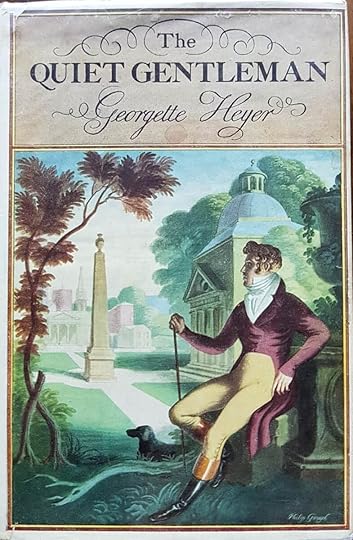

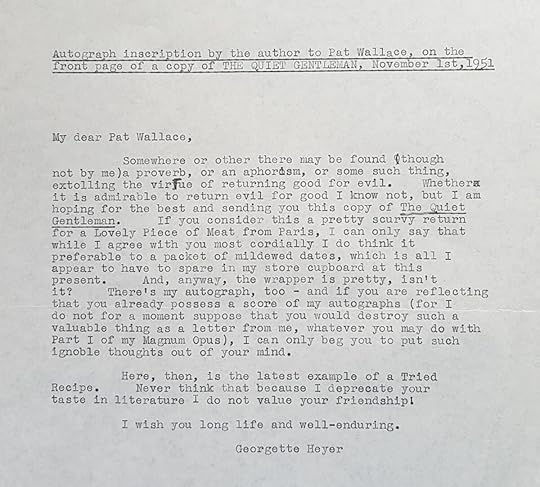

The Quiet Gentleman – an unexpected heroine

After the huge success of Friday’s Child in 1944, Georgette Heyer had become a regular on the bestseller lists with a reputation for producing a sparkling new novel annually. Although she had regularly written two books a year between 1932 and 1941, by her mid-forties she had found this regime of writing too demanding. Consequently, she had reverted to writing just one book a year and taking off the entire summer to rest and recreate. In 1951, for the first time in ten years, she decided to write two novels. The first was a clever murder mystery, Duplicate Death (see my previous blog) and the second was to be her tenth book set in the English Regency which she would call The Quiet Gentleman.

The 1951 Heinemann first edition of The Quiet Gentleman. Gervase Frant, Earl of St Erth

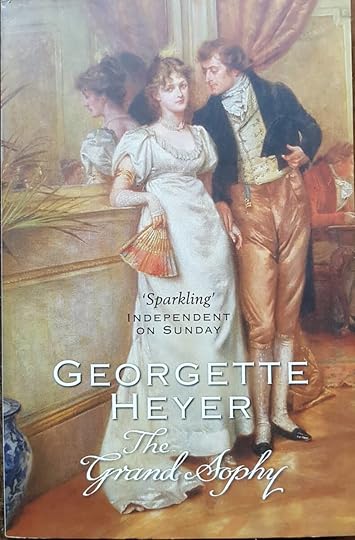

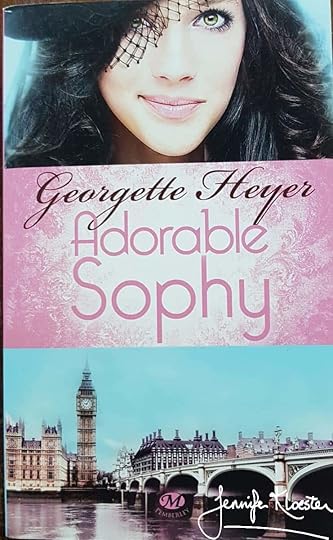

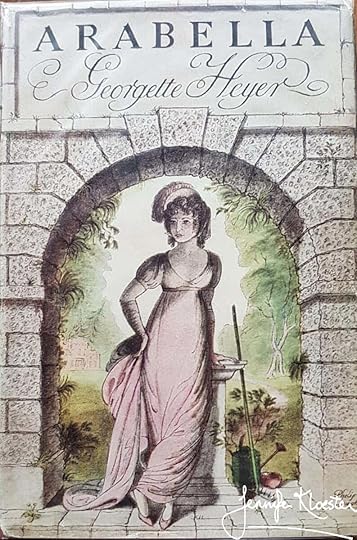

The 1951 Heinemann first edition of The Quiet Gentleman. Gervase Frant, Earl of St ErthLike The Reluctant Widow and The Foundling, The Quiet Gentleman is one of Georgette’s rural novels. Gone is the glittering London scene so brilliantly brought to life in Arabella and The Grand Sophy, instead, the reader finds herself in prime hunting country in the rural fastness of beautiful Lincolnshire. Stanyon Castle is the setting for the novel and is described on page one as a mansion comprised of the remains of a medieval fortress incorporated into a Tudor manor and “enlarged and beautified” by succeeding generations. It has been home to the Earls of St Erth for several centuries; the old Earl has died and his son from his first marriage, Gervase Frant, has inherited the title, much to his half-brother Martin’s disgust. Gervase has been away, fighting in the Napoleonic Wars, and contrary to his brother’s and step-mother’s hopeful expectations, has survived every encounter with the enemy. Ironically, it is not on the battlefields of Belgium that Gervase finds his life in danger, but within the environs of his newly-inherited castle. Perhaps because she had just written another of her detective novels, Georgette decided to incorporate a mystery into her historical novel and there are soon several attempts on Gervase’s life. Though the mystery is slight, solving it proves difficult, not least because Martin’s antipathy towards his half-brother on account of Martin having been raised to think of himself as the true heir to Stanyon. Martin, at nineteen, is the same age as Georgette’s son, Richard, and there are many moments when the author reveals her insight and understanding of a young man’s sometimes highly-charged feelings and the thoughtless impetuosity of youth. Georgette enjoyed writing The Quiet Gentleman, though she could not resist adding a note of self-deprecation to what is otherwise a positive letter to her publisher about the novel:

You know, I don’t altogether dislike this effort. I mean, I haven’t had to fumigate the house, as I did when Sophy lay about it. it’s mere trifling, of course, and Miss Morville is not at all a lively type; but the thing has got a plot, which is an improvement on Sophy; and I fancy the Fans will go a bundle on the Earl of St Erth.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 25 April 1951

The 1966 Pan edition of The Quiet Gentleman“What I’ve written reads nice!”

The 1966 Pan edition of The Quiet Gentleman“What I’ve written reads nice!”By the 1950s, Heyer’s propensity for self-deprecration had become habitual. It was unfortunate that she felt the need to speak slightingly of her books, for her comments what not reflective of her real attitude to her writing. As discussed elsewhere, Georgette Heyer loved writing and she especially loved writing her Regency novels. One of the main sources of her self-deprecation was the unquestioning acceptance of her manuscripts by her agent and her publisher. At some point in the 1930s, they mostly stopped reading her books and simply forwarded any manuscript Heyer sent to them straight to the printers. Georgette never had an editor, but throughout her long career, she never stopped wanting someone other than herself and Ronald (after her father’s untimely death in 1925, Ronald was always her first reader) to read and respond to what she had written. The Quiet Gentleman was her thirty-eighth novel; her publishers obviously had complete faith in her ability to hand them a clever, well-written book guaranteed to sell in huge numbers to her of eager readers. Georgette, however, set a high standard for herself and refused to rest on her laurels:

I don’t advise you to tackle the Q.G. in typescript: you’ve got the top copy, but I’ve mauled it a bit! When you do read it, let me know what you think! I’ve probably reached the time of life when I ought to be very careful not to kid myself into thinking that what I’ve written reads nice! One never knows: one could, I suppose, become mechanical, and not perceive it.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 25 April 1951

The 1966 Pan edition of The Quiet GentlemanFresh and witty

The 1966 Pan edition of The Quiet GentlemanFresh and wittyShe never did become mechanical and her writing remains fresh and witty – a testament to her skill as a writer and storyteller – and Heinemann, of course, published The Quiet Gentleman with their usual alacrity. Despite her plea for his opinion of the novel, Frere did not read it and nor did the Head of Editorial, Arnold Gyde. Gyde was tasked with writing the blurbs for Georgette’s most recent novels and had earned a compliment over his effort for The Foundling, a novel of hers that he does seem to have read – at least in part. However, when The Quiet Gentleman arrived at Heinemann, Gyde handed the manuscript to his adolescent son, Humphrey, and asked him to read it and make notes so that Gyde could write the blurb. Years later, Humphrey vividly recalled the experience and its rather unfortunate aftermath:

I can tell you that I read one of her novels and made notes for my father to enable him to write a suitable

Humphrey Gyde to Jennifer Kloester, email, 17 December 2005

blurb for publication. Unfortunately I transcribed the name of a character as the nth Earl of St Something instead of the n+1th and this apparently caused an angry and hurt letter to be sent to Heinemann’s and my father to make some comment to the effect that he had not realised that she took her work so seriously.

The 1971 Pan edition of The Quiet GentlemanArnold Gyde of Heinemann

The 1971 Pan edition of The Quiet GentlemanArnold Gyde of HeinemannArnold Gyde was always kind, well-intentioned and earnest and he worked hard to please Georgette, whom he admired but about whom he had no illusions. He descibed her in his diary as “she wants to be Georgette Heyer making a lot of money, she also wants to be Enid Bagnold the artist added to Carola Oman the historian.” He thought of her as an intellectual but in his diary he also wrote that in his opinion she was a person “with something essentially vulgar in her, something very sharp, something very acquisitive – a real woman as you find ‘em.” Another observation – which he later crossed out – read: “I always have a feeling that she would like me to make a pass at her.” In 1952, several months after the publication of The Quiet Gentleman, at the opening of Heinemann’s new Windmill Press at Kingswood in Surrey, Georgette and Arnold Gyde reached a lasting understanding. As Gyde recalled:

I had a ghastly time recognising those who thought I knew them very well…….No one helped me……. Frere as Chairman should, keeps entirely with the few “big authors” and I alone know all the rest or should say, ought to know the rest. This leads me to the terrible climax. “Who’se that fine looking woman? asked Noel Baker. So I introduced him. I was exhausted. I confused him with Black of the The Daily Mail and said:

“May I introduce you to Mr Black – Lady Jones, whose pen name is Enid Bagnold”.

“Well’ she replied “I am not Enid Bagnold”.

“Nor am I Mr Black”, said Noel Baker.

It was Georgette Heyer!

So this was a terrible moment. What was I to do? Run away into the bushes? “Well”, I said, “this is surely game and set in the Memory Stakes”.

After this the old girl was very courteous and queenly: “How is your son, the Regular Officer in HongKong? And your younger son at Haileybury?”

Then, thank God, I remember that hers is in the 60th. Rifles and ask how he is. We part amicably, but I know she will make a great story of this. Furthermore she does.

Arnold Gyde, diary entry, 25 June 1952

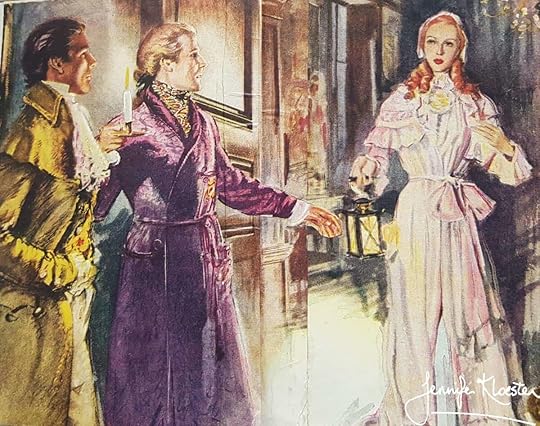

I love this picture of Drusilla meeting Gervase and Martin by candlelight after she is woken in the middle of the night.Drusilla and the Pantisocrats

I love this picture of Drusilla meeting Gervase and Martin by candlelight after she is woken in the middle of the night.Drusilla and the PantisocratsDrusilla Morville is one of Heyer’s more unusual heroines as well as one of her drollest. Practical, kind and with a great deal of common sense, at first she takes an unassuming role in the story. Overshadowed by the lovely Marianne Bolderwood, the reader does not immediately recognise Drusilla as the heroine of the novel. But an unexpected sense of humour and an acute intelligence gradually bring her to the fore and into St Erth’s notice. Drusilla is unique in the Heyer canon for having liberal, socially-progressive parents and Heyer creates several very witty scenes in which Drusilla reflects on the impracticality of the Pantisocrats and the irrationality of geniuses such as “Miss Mary Lamb, who murdered her mama, in a fit of aberration. Then, too, Miss Wollstonecraft, who was once a friend of my mother’s, cast herself into the Thames, and she, you know, had a most superior intellect.” I have always loved Drusilla for her plain speaking and unshakeable honesty, as well as for her marvellous account of Mr Coleridge and Mr Southey’s ill-fated plan to establish a community on the banks of the Susquehanna River and why it was doomed to fail. It is obvious that Georgette had been reading deeply prior to writing the novel and she obviously found great enjoyment in weaving such real-life figures into her story. The Quiet Gentleman is not entirely in the established Heyer vein, but it is replete with delicious moments and nuggets of pure comedy and Heyer herself said of the novel:

My own favourite is the Dowager. I got quite fond of her! Altogether, I enjoyed writing it

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 25 April 1951

A transcription of the handwritten dedication in Miss Wallace’s edition of The Quiet Gentleman.

A transcription of the handwritten dedication in Miss Wallace’s edition of The Quiet Gentleman. The 2005 Arrow edition of The Quiet Gentleman

The 2005 Arrow edition of The Quiet GentlemanApril 23, 2021

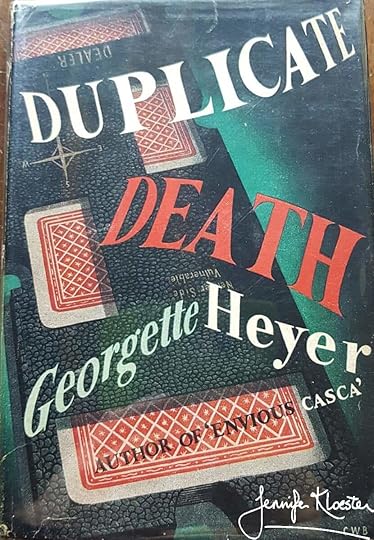

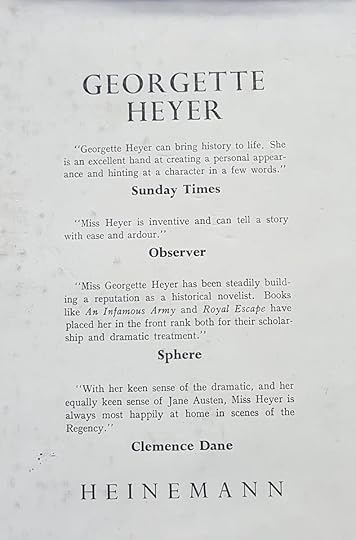

Duplicate Death – “an intricately-devised plot”

“In an intricately devised plot, written in her definitely elegant style, Miss Heyer triumphs once again in her earlier metier. The duplicate-bridge party given by a dubious social-climbing hostess is the scene for double murder. Inspector Hemingway is at his rueful best in sorting out the grab-bag of ill-assorted characters, all of whom have very good reasons for not being entirely co-operative. In attempting to beat the Inspector at his own game, the reader has no easy task, particularly as the second victim seemed the logical choice in accounting for the first murder. Duplicate Death is an intriguing story.”

“Clue Works” Bestsellers 29, 15 June 1969. Review of the 1969 USA Dutton edition.

The 1951 Heinemann first edition cover of Duplicate Death.A rare sequel!

The 1951 Heinemann first edition cover of Duplicate Death.A rare sequel!Late in 1950, Georgette Heyer began writing a new novel. For the first time in almost ten years, she had decided to write a murder mystery and, unusually for her, she chose to make it a sequel. In her long career, Georgette wrote only a handful of sequels – and not all of them entirely met readers’ expectations of what a sequel was meant to be. These Old Shades was originally intended as a sequel to The Black Moth, but it may more accurately be described as a sort of reinvention; Devil’s Cub is definitely a sequel in the accepted sense to These Old Shades and is an eminently satisfying new chapter in the lives of the Alastairs. Georgette brought Dominic Alastair on stage again in An Infamous Army, which she described as ‘not precisely a sequel’ and later admitted ‘that Dominic couldn’t have had grand-children of mature age in 1815’. Still, An Infamous Army is a sort of sequel to Devil’s Cub and is definitely a sequel to Regency Buck. In An Infamous Army we again meet the main protagonists from Regency Buck, Lord and Lady Worth, as well as several other characters from that novel. In 1942, Georgette had planned to write a sequel to Penhallow in order to tell Bart’s story, but when Penhallow did not achieve the suces fou for which she had hoped, she dropped the idea. Although, by 1950, Georgette had thought of writing Ferdie’s story from Friday’s Child, that book had not yet come to fruition. Instead she decided to write a sequel to her 1937 detective novel, They Found Him Dead. The new book was called Duplicate Death.

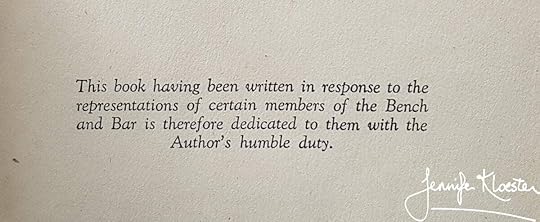

Georgette Heyer’s dedication at the beginning of Duplicate Death.For “Bench and Bar”

Georgette Heyer’s dedication at the beginning of Duplicate Death.For “Bench and Bar”By 1950, when she began writing Duplicate Death, Ronald had been working as a barrister for eleven years. His office was in the old and historic Paper Buildings in the Inner Temple at the centre of London’s legal world. Georgette’s hero in Duplicate Death, Timothy Harte, is also a barrister with chambers in Paper Buildings. She offers a description of Timothy and his room there that may well have described Ronald’s own office and even Ronald himself:

“a comfortable room overlooking the garden, which smelt of tobacco and leather, and was lined with bookshelves…An aged Persian rug covered most of the floor, and a large knee-hole desk stood in the window. Young Mr Harte, in the black coat and striped trousers of his calling, was seated at this, smoking a pipe, and glancing through a set of papers, modestly prices at 2 [guineas].”

Georgette Heyer, Duplicate Death, einemann, 1951, p.111.

Ronald, too, smoked a pipe and, as Jane Aiken Hodge perceptively pointed out, “If this was the kind of fee Ronald could command, it is not surprising that every penny his wife earned counted.” Whether that was so or not, Ronald’s profession meant that he, and by extension Georgette, often socialised with “members of the Bench and Bar”. Although Ronald was not an Oxbridge man, he had been to Marlborough and to Dartmouth (where he had been in the same class as Lord Louis Mountbatten), and though his Russian birth and background were somewhat exotic, he was a first-rate golfer and a sound bridge player. These were the sorts of things that mattered in the rarefied world of the Inner Temple and among London’s legal fraternity. In time the Rougiers became friends with lawyers and judges and Georgette discovered, to her immense satisfaction, that she had an enthusiastic readership among Members of the Bench and Bar. Among her most avid readers were Lord Justice Somervell and Sir Edward Anthony “Tony” Hawke. When he died, Lord Somervell bequeathed his entire collection of Heyer novels to the Inner Temple library, and it was for Tony Hawke that Georgette wrote Duplicate Death.

Sir Edward Anthony “Tony” Hawke, the photo is from the National Portrait Gallery.

Sir Edward Anthony “Tony” Hawke, the photo is from the National Portrait Gallery.As she told her publisher, A.S. Frere of Heinemann, late in 1950, she had obliged her eminent fan and promoted her detective to a new rank:

Herewith one Detective Novel, between 90,000 &100,000 words. I think I have done better, but I know I have done worse; & I have little doubt that it will sell a treat. Ronald has been carefully through it, to make sure that I have dropped the requisite clues; & he has O.K.’d it. I hope you’ll like it. You have never read Miss Heyer’s Masterpieces of Detection, so I must inform you that Hemingway is a well-known figure to my Fans. When I last wrote of him he was an Inspector, but Tony Hawke, who badgered me for this book, says he is now a Chief-Inspector. So I dutifully made him one.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 10 December 1950.

The gorgeous and entirely accurate (for once!) cover of the 1954 Pan edition.A delightful domestic scene

The gorgeous and entirely accurate (for once!) cover of the 1954 Pan edition.A delightful domestic sceneSet thirteen years after They Found Him Dead, Georgette opened Duplicate Death with a delightful domestic scene where we again meet Jim Kane, murder suspect in the earlier book, and now happily married to Pat. We learn that he has served with distinction in the Second World War and lost part of his leg in Monte Cassino.

“Mr James Kane rose from the table, with the slight awkwardness peculiar to those who had left part of ther left legs to be decently interred in enemy soil. What Mr James Kane secretly thought of his loss he had divulged to none, his only recorded utterance on the subject being a pious thanksgiving to Providence that he had an artificial leg to raise him, in the eyes of his progeny, above the spurious claims to distinction of their Uncle Timothy.

Georgette Heyer, Duplicate Death, Heinemann, 1951, p.9.

It was rare for Georgette to write about the harsh realities of the war or to give anything other than glib responses in her letters to such things as being bombed or losing a loved one at Dunkirk. That was her nature – stoic in the face of trouble and never wanting her deepest wounds touched. A close reading of Duplicate Death, however, reveals more than usual including a poignant tribute to Jim’s younger brother, Timothy, whom Pat obviously adores: “I shall never forget how angelic he was to me all through that ghastly Dunkirk time, and how he gave up two whole days of his leave to come and see me in that disgusting place I took the children to when you were in Italy.” Timothy, too, has served in the War as a Commando. But it’s not only personal reminiscences of the War which Georgette weaves into the early pages of Duplicate Death. The opening chapter also includes an endearing account of Mrs Kane reading letters from her sons. Both boys are at boarding-school and there is a strong sense that the letters and their mother’s reaction to them are a reflection of Georgette’s own reaction to her son Richard’s letters which he used to write her from boarding-school. Richard was eighteen when his mother wrote Duplicate Death but when he was younger, like young Silas Kane, Richard also wrote to his mama about his sporting achievements, asked her to send him stamps for “swops”, urged her to find some lost item now desperately needed, failed to answer her urgent enquiries about his health and grappled with his Common Entrance Exam.

My son is this day taking his Common Entrance exam, & if the spelling is to be comparable with what I get from him he’ll have to be privately educated. I asked him for the measurements of his trousers, & this is what I got: “Waste (loosly) 27”. It baffles me. I never had the least difficulty in spelling, & feel I’ve bred an illiterate. And yet – when my mother asked me if I remembered a play, saying: “Do you remember the Great Lover?” Richard looked up and said: “Oh, quite one of my favourites! You mean, ‘There you have loved’?”

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 18 June 1945.

Georgette, Ronald and Richard at dinner, circa 1947.Chief-Inspector Hemingway & “Terrible Timothy”

Georgette, Ronald and Richard at dinner, circa 1947.Chief-Inspector Hemingway & “Terrible Timothy”In 1937, when she wroteThey Found Him Dead, Georgette’s detectives were Inspector Hannayside and his clever assistant, Sergeant Hemingway. The two men were very different but it was Hemingway who remained as the lead detective in the ensuing novels (with the exception of Penhallow) and whose character Heyer developed most fully. Hemingway is clever, witty and perceptive although this is not always obvious to his suspects. He likes to talk, has an excellent memory for faces, is an avid reader (he knows his Dickens) and theatre-goer, and is fascinated by psychology. Heyer herself must have had some understanding of this branch of science for at one point she has Hemingway make a very funny speech in which he mentions Wendt, Munsterburg, Freud and Rosanoff, and tells his suspect that “I know you don’t belong to the Autistic Type, I haven’t had time yet to decide whether you’re Anti-Social, or Cyclothymic, but I daresay I’ll make up my mind about that presently!” Hemingway first encountered Timothy Harte in They Found Him Dead when Timothy was an irrepressible fourteen-year-old with a penchant for American gangster movies. In that novel he became known as “Terrible Timothy”, in Duplicate Death he is now 27, a War veteran and a respectable lawyer. He is also in love with the mysterious Beulah Birtley, secretary to the first murder victim, and a prime suspect in the case. Beulah is an original among Heyer’s heroines and her relationship with Timothy is rocky from the start. She is a mystery, but as with all of the best men in Heyer’s oeuvre, he is clear-sighted and knows a good woman when he sees one. His family are not so sure and Timothy’s mother – making an off-stage reappearance after her cameo in They Found Him Dead – is inclined to strongly disapprove of her younger son’s new flame. The story becomes suitably tangled and the second murder is decidedly more puzzling than the first!

Taxation troubles

Taxation troublesIt has sometimes been said that Georgette Heyer wrote her novels only for financial gain. This is not true. First and foremost, Georgette was a writer. She was – as Philippa Gregory has said – born to write. She was not only a compelling writer but also a compulsive one. Heyer loved to write and her novels flowed from her brain precisely for that reason. Twice, however, she felt compelled to write something quickly in order to meet the latest tax demand. Duplicate Death and her last detective novel Detection Unlimited were written for that reason. During the Second World War the taxation rate peaked at 99.25% and even after the War the top rate was reduced only slightly to just above 95%. Anyone earning above a certain amount (Heyer cites it as £5000) paid nineteen shillings and sixpence in for every pound earned above that amount. Faced with a large tax bill in 1950, Georgette decided to write a detective novel in the hope of earning enough money to meet the demands of the Treasury. In the years to come, as her income increased, these demands would grow ever-larger and, to Georgette’s mind, increasingly stressful. She loved writing but she did not enjoy writing to pay the taxman such a large proportion of her income! By the 1970s, the high level of taxation in the UK caused many creative people to leave Britain for countries with lower tax rates. At times, Heyer, too, felt the pull of the tax haven, but she was too much of an Anglophile to ever leave her home and country.

“Tax, under the Labour government of Wilson was 93% if you earned a million quid, which we didn’t, you’d end up with 70 grand. So it was impossible to earn enough money to pay back the Inland Revenue and stay here, in England.”

Bill Wyman, Rolling Stones bass player, Stones in Exile, movie, 2010.

Georgette did, however, vent her spleen a little in Duplicate Death in which there are a few acerbic mentions relating to the high rate of tax: “This was shown to be much too large in an epoch when not the largest fortune was permitted to yield its owner more than five thousand pounds yearly…”

A claim of libel!

A claim of libel!“Don’t name Mr Lowick, because if you do, I said, I shall refuse to act. Mr Lowick is the junior partner, and when I tell you that the day I went up to see him about the ground-rent he not only kept me waiting for ten whole minutes, but he received me with his pipe in his hand, you will understand why I said what I did. There are limits!”

Miss Pickhill explaining her objections regarding Mr Lowick to Chief-Inspector Hemingway in Duplicate Death, 1951, p.210.