Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 51

February 1, 2011

The Grim Handiwork of Man

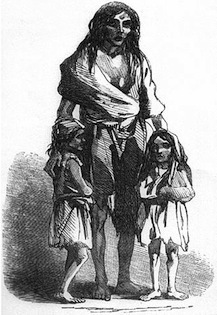

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal's rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for "Piano Demon,", however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill's malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India's burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal's rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for "Piano Demon,", however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill's malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India's burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

As I waded back through my notes on the Bengal famine, I became more interested in examining a frequent assertion of modern historians: that all famines are created by man, rather than nature. That line of inquiry led me to this thorough look at the Vietnamese famine of 1945, a little-known calamity that played a big role in establishing the Communists' moral legitimacy in the countryside. The author contends that while bad weather and a population boom certainly made the food-security situation tricky, mass hunger could have been avoided if the Vichy French and the Japanese had been less avaricious—and had the Americans realized that their bombing campaign would make any relief efforts impossible. The sum-up:

Even if Tonkin had become increasingly dependent upon imports of Cochinchina rice over the previous two decades, France can hardly be blamed for the demographic increase in the north. Assessing responsibility for the famine is further complicated by the US recourse to bombing in Indochina that often did not discriminate between civilian and military targets. In fact, the Americans were warned by the French of the consequences of destroying dikes in the north. Finally, there remains the difficulty in interpreting the willful destruction of rice stocks at war end by the Japanese military.

It is nevertheless clear, however, that continued heavy rice requisitions demanded by the Japanese and implemented by the Vichy French in a situation of administrative breakdown and even semi-anarchy after the Japanese coup, magnified the impact of the disaster. Human failure and agency combined to betray the people of northern and north-central Vietnam. Affirming perhaps the more general thrust of Amartya Sen's arguments about the causes of famines, food distribution mechanisms broke down not in a situation of absolute scarcity as in some conflict situations but in an environment in which all signs pointed to the urgent need for surplus rice to be moved north from the Mekong delta. More than that, more rational and humane policies directed at northern Vietnam would have seen more land under rice cultivation, less rice diverted to industrial alcohol, etc., corn and other crops planted and reserved as a backup, reduction of rice exports under shortage conditions, fewer forced deliveries, greater availability of food crops in the marketplace, and the rational and humane use of stockpiled rice.

I'm still on the fence as to whether it can be categorically asserted that all famines are entirely preventable. But it's clear that some of the worst famines in recent history were, indeed, tragedies that could have been averted had a scrap more attention been paid to such matters as logistics and basic economics. Had such care been paid to Vietnam in 1945, the nation's postwar fate would likely have been very different.

January 31, 2011

Monroe

In transit back from a Now the Hell Will Start reading in Monroe, N.C.—birthplace of Herman Perry, the book's main character. More tomorrow; in the meantime, check out the above—a tribute to Teddy Weatherford's heyday in Calcutta, when "The Seagull" starred at the Grand Hotel. It's the handiwork of close pal and fellow traveler Susheel Kurien, who's currently putting together a movie about the hidden history of Indian jazz.

January 24, 2011

Over There

I'm guesting over at Ta-Nehisi Coates' Atlantic blog this week, so please pop over there for your daily dose of Microkhan. I'll cross-post at some point, but probably not 'til week's end—just too busy doing last-minute debugging on the Teddy Weatherford tale.

January 21, 2011

Flying with the Seagull

I wasn't going to start plugging my next major project 'til next week, as it won't be going live 'til Wednesday the 26th. But this piece sort of blew our cover, plus a pending guest shot over at Ta-Nehisi Coates' blog threatens to complicate matters, so I've decided to end the week with a not-so-hard sell.

What I've got cooking is difficult to describe: a multimedia non-fiction story about a child coal miner who became the most famous jazz musician in Asia during the '30s and '40s. It will initially be available in one of two ways—for iPads and iPhones through The Atavist's app, or as a Kindle single. If you have the hardware, I highly recommend the tablet version, which I've been carefully vetting these past few days. It really is a whole new form of storytelling, enriched by images, music, and hypertext that dead-tree publications can't possibly hope to provide. This is about as close as us writers can get to cinematic without actually employing a 35mm camera.

I'll have plenty more details to share around the 26th, including the backstory of how the piece came together, plus thoughts about what this all means for the future of my chosen trade. For the moment, though, let me just leave you with two snippets from the tale, starting with a note from the chapter simply entitled "Chicago":

The era's most outlandish anti-jazz screed appeared in the normally tame Ladies Home Journal, which lambasted the music as outright barbaric: "Jazz originally was the accompaniment of the voodoo dancer, stimulating the half-crazed barbarian to the vilest deeds. The weird chant, accompanied by a syncopated rhythm of the voodoo invokers, has also been employed by other barbaric people to stimulate brutality and sensuality. That is had a demoralizing effect upon the brain has been demonstrated by many scientists."

And secondly, a somewhat context free line culled from a chapter describing the decadence of prewar Shanghai:

Their sexual abandon had predictible consequences: Band members paid frequent visits to one Dr. Borovika, a former German fighter pilot turned physician who was a master of treating venereal diseases.

More next week, for sure. But don't worry, I'll also be feeding y'all posts about chess hustlers, dumb criminals, and North Korean card stunts. Microkhan always aims to please.

January 20, 2011

The Rickshas Tell All

I'm a big fan of the theory that the key to understanding societal shifts is to pay close attention to the art of the everyday. A Chinese politician who may or may not have been Deng Xiaoping is credited with summarizing this logic during the sunset of Mao Zedong's reign, when he was asked to comment on the import of Beijing's omnipresent wall posters: "If one knows the nuance, the walls tell all."

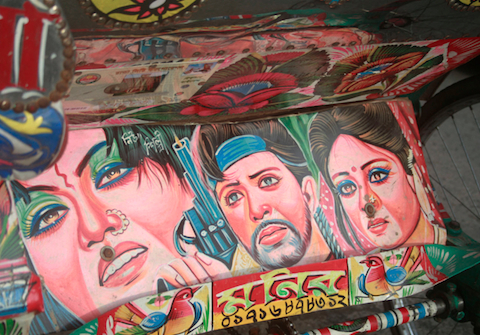

Several months back, I copped that line for a post about the supposed wisdom contained in bathroom graffiti. Today I turn Microkhan's attention to a far more gorgeous art form: the festooning of rickshas in Bangladesh. Joanna Kirkpatrick, the West's leading authority on the matter, argues that observers of the teeming South Asian nation would be well-advised to note trends in ricksha art:

Ricksha arts flow with the times, and what one sees on many of the vehicles often reflects current political passions or conflicts. Widespread decoration of rickshas began during the separation from Pakistan, when the doyen of ricksha artists in Dhaka, R.K. Das, began portraying battle scenes. Many rickshas of that era bore paintings of Mukti Bahini fighters in action. Others simply showed scenes of air or sea combat, the new Bangladeshi flag, or animals in combat.

Ricksha decoration continued, with one fad following another: first movie scenes, then birds on every panel, then fantastic Himalayan landscapes, animal fables, and futuristic city scenes with crisscrossing aerial roadways, complete with rushing trains, buses, minivans and stretch limousines, usually colored bright red. (Lately, compact cars have begun replacing the limousines in such scenes.)

Kirkpatrick adds here that a trend of more recent vintage is rickshas that celebrate jihadism—surely a worrying trend in a nation with the world's fourth-largest Muslim population.

(Image via this fantastic gallery)

January 19, 2011

Hocus Pocus

Should you ever find yourself digging through the Vanuatuan penal code, you might notice a curious offense listed in Section 151: "No person shall practice witchcraft or sorcery with intent to cause harm or detriment to any other person." Though this prohibition obviously has its roots in traditional Vanuatuan culture, it's inclusion in the nation's official statutes is of far more recent vintage: The penal code was crafted in 1981, just a year after Vanuatu gained its independence.

The criminalization of witchcraft seems dreadfully archaic to my American ears. But writing in the LAWAISA Journal, the Australian legal scholar Miranda Forsyth makes the case that such a ban is actually smart policy:

There are a number of factors that indicate that the practice of sorcery should continue to be criminalised in Vanuatu. Sorcery is considered to be a serious crime by the majority of the population and as discussed above is a source of considerable community disorder and fear. As the Papua New Guinea Law Reform Commission observes "[w]hat is important about the existence of sorcery is not that it can be proved objectively and mathematically, but rather that the subjects and the objects of sorcery believe it exists and is effective, for good or for ill." Further, the criminal law has always recognised through the doctrine of attempt that a person who intends to harm someone but is stopped before they actually cause harm is just as guilty as someone who actually causes the harm. Given that legitimacy is a major issue for the state legal systems in Melanesia, effectively criminalising behaviour widely perceived to be evil would certainly be a step in the direction of giving ownership of the state system to the people…Finally, if sorcery is not criminalised then people who honestly believe that they are the victims of sorcery will have nowhere to turn and may as a consequence engage in vigilantism. It would appear to be manifestly unfair for a legal system to provide no means of redress for a person who believes his or her life is at risk, but then to punish that person if he or she takes steps to protect themselves from that risk.

Forsyth adds that Section 151 is almost entirely for show, as there has never been a successful sorcery prosecution in Vanuatuan state courts. (The "customary" courts that exist on the village level are apparently a different story, however.)

Reading about Vanuatu's symbolic anti-witchcraft stance made me curious about when and how similar laws slid off the books of Western nations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pattern was similar: Sorcery remained technically illegal long after state legal systems stopped caring about such "crimes":

The formal decriminalization of witchcraft had little bearing on the broader process of decline that we have been discussing. The blanket repeals that took place in Great Britain and Sweden had no effect whatsoever on witchcraft prosecutions in those countries because the last trial had long preceded the legislation effecting the change. The same could be said of the large number of states which repealed their laws only in the nineteenth century. Even in those countries which passed witchcraft statutes before the end of the trials, the new laws had only a limited effect on the volume of prosecutions. The first of these laws, the French edict of 1682, probably prevented prosecutions only in the few outlying regions of the country where trials were still taking place. The same could be said of Frederick William I's edict of 1714, since prosecutions in Prussia had slackened considerably since the 1690s. The Polish law of 1776 affected only those isolated villages like Doruchowo where there was still pressure to prosecute.

The lesson here? Laws are often the carts behind the horses. Real-world attitudes develop too quickly for the machinery of government to keep pace, something that smart officials recognize by stretching (or ignoring) the rules in place. Were legal originalism to always reign in day-to-day practice, the world would be a much more unbearable place.

(Image via Sense and Sensibility)

January 18, 2011

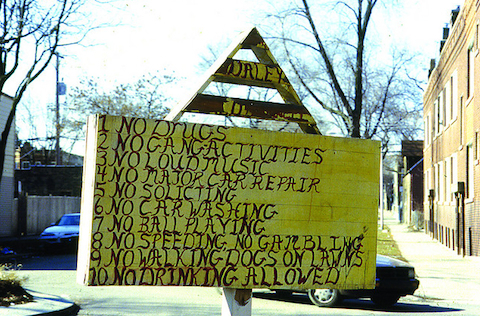

House Rules

Got lots of good stuff lined up for the coming days, including posts about syphilitic composers, porcine economics in the New Guinea highlands, and the latest in ostrich ranching technology, to name just a few. And I'll be moving the show over to Ta-Nehisi Coates' space at The Atlantic next week, so keep an eye peeled for that. But I need to be quick for today, as I'm vetting the almost-final version of my upcoming Jazz Age yarn, plus prepping for a big meeting 'bout the next major project. So content yourselves today with a peek at Chicago block club signs, loving collected by the good folks over at Temporary Services. You probably know TS best for their awesome work in documenting the technical ingenuity of inmates, but they've also done an admirable job of chronicling the ways in which Americans, Mexicans, and Slovenes save parking spaces and erect basketball hoops. It takes a special kind of genius to realize that this sad plank deserves to be immortalized in bits.

January 14, 2011

How to Wreck a Nice Atoll

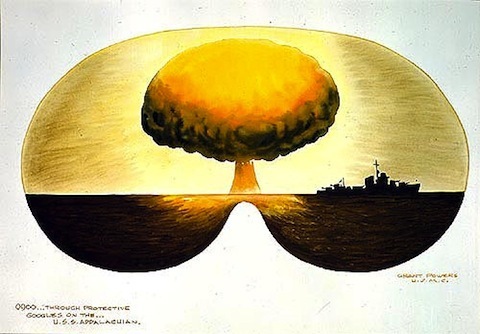

Followers of Microkhan's microblog may have noted that I've developed a recent fascination with World War II-era combat art, which was created as part of an official War Department program to depict the conflict in oils, inks, and water colors. Once the the war was over, the painting continued as the U.S. speedily developed its nuclear weapons program, most notably by conducting atmospheric tests in the South Pacific. Three Naval artists were commissioned to record the destruction of Bikini Atoll in 1946; their work is now collected here.

The artists captured not only the ethereal beauty of the mushroom clouds, but also the damage wrought upon the ships that were placed in the explosions' paths. Notably lacking from the collection? Any sense of the human toll caused by the evacuation of Bikini Atoll. We only get one glimpse of an abandoned village, where intact longhouses stand adjacent to a fluttering American flag. And then a painting of American military personnel at play. Yet there is a hint of malice to these paintings, a sense that the artists knew that they were bearing witness to events that would have unforeseen repercussions. There is no triumphalism in these artworks, only quiet awe.

More thoughts on the collection here, from a blogger with a keen interest in mushroom cloud kitsch.

Blaming the Better Half

I've spent a fair chunk of the morning immersed in the goings-on in Tunisia, where embattled President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is rapidly losing his grip on power. What strikes me most about the protests is the fact that so much rage has been directed at Ben Ali's wife, the former Leila Trabelsi, a onetime hairdresser who has leveraged her marriage to greatly benefit her family's fortunes. Tunisia's opposition has targeted her as a symbol of everything that has corroded their nation's political culture: cronyism, nepotism, outright greed. While Hell might have no fury greater than a woman scorned, a frustrated public's anger at a spendthrift quasi-dictator's life surely comes in a close second.

I've spent a fair chunk of the morning immersed in the goings-on in Tunisia, where embattled President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali is rapidly losing his grip on power. What strikes me most about the protests is the fact that so much rage has been directed at Ben Ali's wife, the former Leila Trabelsi, a onetime hairdresser who has leveraged her marriage to greatly benefit her family's fortunes. Tunisia's opposition has targeted her as a symbol of everything that has corroded their nation's political culture: cronyism, nepotism, outright greed. While Hell might have no fury greater than a woman scorned, a frustrated public's anger at a spendthrift quasi-dictator's life surely comes in a close second.

The vilification of Ben Ali's wife harkens back to a brief period in the mid-1980s when two of her predecessors helped cause their husband's political demises. There was Imelda Marcos and her shoe collection, of course, but the character I find more fascinating is Michèle Duvalier. One of the most iconic photojournalism images of my youth was that of Mrs. Duvalier and her portly, slow-witted husband driving to the Port-au-Prince airport in a silver BMW, so they could flee the country just ahead of the mobs who would surely have caused them great harm. As in contemporary Tunisia, the public had had enough of the First Lady's covetousness:

Michèle always loved money, but in the first two years of her marriage, she spent a good bit of it on the needy. Her Michèle B. Duvalier Foundation supported hospitals, clinics and pharmacies, and she made frequent inspections to ensure that they operated efficiently. But Michèle's largesse soon took a bizarrely baroque turn. She would appear on TV dressed to the nines, handing envelopes of money to the indigent. And her attire bloomed garishly. "I remember her all in silver—and this for a 5 o'clock reception," sniffs one stylish Haitian. Another comments, "She had too many things, and she thought she had to wear them all at once. It was a delirium she was in all the time." The delirium got worse. "She would buy truckloads of dresses from Valentino. She had Boucheron, the Paris jeweler, fly to Haiti to sell jewels to her—not $200,000 worth but millions, millions," says a Haitian socialite. Another friend tells of buying dozens of pairs of $500 Susan Bennis Warren Edwards shoes for Michèle during a shopping foray on Park Avenue. "She wore earrings that looked like lanterns," says Suzanne Seitz, a Port-au-Prince hotel owner.

A country may grumble loudly at a dictator's corruption and self-enrichment, but it simply won't countenance having its nose rubbed in this sad fact by the wastrel who shares his bed. Since President Ben Ali didn't understand that, perhaps he'll soon be bound for the Tunis airport under cover darkness. Though I very much doubt he'll be driving his own car, à la Baby Doc.

Update Annnnnddddd…he's gone. Shouldn't be long before his minions show up at various Swiss banks, with withdrawal slips in hand.

January 13, 2011

The Importance of Good Design

A salient reminder that engineering details really matter, from the august (and 141-year-old) pages of The Field Quarterly Magazine and Review:

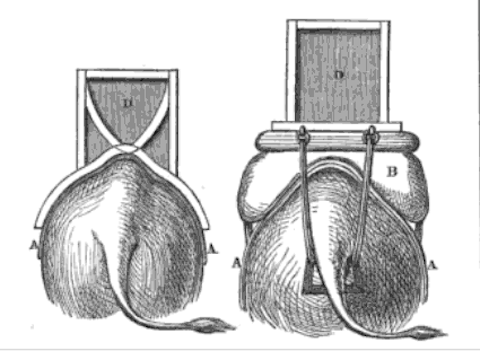

The Hindustani howdah often requires six men to place it on the elephant's padded back. The Siamese "shing kha" can be easily lifted by two persons, and this while the elephant is standing—a great advantage, especially on stony ground. The difference of weight also is such, that a Burman or Siamese elephant is comparatively fresh when the heavily caparisoned Bengal animal is quite done up for the day. All this difference, to the advantage of the shing kha, arises simply from its being made on the principle of the saddle tree, and so fitting home to the sides of the elephant's back; whereas the howdah, being built on a flat frame, rests balanced on the animal's vertebrae, and has to be propped and cushioned on each side of that ridge. The preceding diagram shows clearly enough the superiority in lightness and tenacity of the former vehicle as compared with the latter.

It will take a great student of Asian military history to comment on whether this design advantage somehow influenced the diverging fates of India and Thailand once European colonialists turned their eyes eastward. But if the stirrup can be credibly credited with making the Mongol Empire possible, it's no great stretch to think that the shing kha helped shape Thailand's political fortunes to some extent. Seemingly minor technological advantages can have profound impacts over time.