The Grim Handiwork of Man

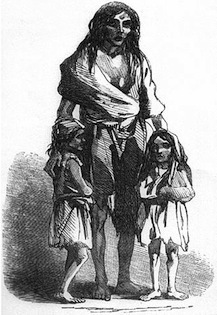

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal's rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for "Piano Demon,", however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill's malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India's burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

In researching my Teddy Weatherford yarn for The Atavist, I was compelled to revisit a tragic event that I described in Now the Hell Will Start: the Bengal famine of 1943, which ultimately claimed the lives of 3 million Indians. In the book, I detail how a bare modicum of foresight could have prevented the catastrophe; the British should have realized that Burma, the source of most of Bengal's rice, was vulnerable to Japanese invasion, and had a contingency plan in place. Delving into the topic once more for "Piano Demon,", however, I came across some scholarship that asserts that the famine persisted due to Winston Churchill's malevolent intervention; the claim is that Churchill viewed the famine as an excellent way to weaken India's burgeoning independence movement, and so secretly urged that nothing be done to feed the suffering Bengalis. (Pointed rebuttal to that argument here.)

As I waded back through my notes on the Bengal famine, I became more interested in examining a frequent assertion of modern historians: that all famines are created by man, rather than nature. That line of inquiry led me to this thorough look at the Vietnamese famine of 1945, a little-known calamity that played a big role in establishing the Communists' moral legitimacy in the countryside. The author contends that while bad weather and a population boom certainly made the food-security situation tricky, mass hunger could have been avoided if the Vichy French and the Japanese had been less avaricious—and had the Americans realized that their bombing campaign would make any relief efforts impossible. The sum-up:

Even if Tonkin had become increasingly dependent upon imports of Cochinchina rice over the previous two decades, France can hardly be blamed for the demographic increase in the north. Assessing responsibility for the famine is further complicated by the US recourse to bombing in Indochina that often did not discriminate between civilian and military targets. In fact, the Americans were warned by the French of the consequences of destroying dikes in the north. Finally, there remains the difficulty in interpreting the willful destruction of rice stocks at war end by the Japanese military.

It is nevertheless clear, however, that continued heavy rice requisitions demanded by the Japanese and implemented by the Vichy French in a situation of administrative breakdown and even semi-anarchy after the Japanese coup, magnified the impact of the disaster. Human failure and agency combined to betray the people of northern and north-central Vietnam. Affirming perhaps the more general thrust of Amartya Sen's arguments about the causes of famines, food distribution mechanisms broke down not in a situation of absolute scarcity as in some conflict situations but in an environment in which all signs pointed to the urgent need for surplus rice to be moved north from the Mekong delta. More than that, more rational and humane policies directed at northern Vietnam would have seen more land under rice cultivation, less rice diverted to industrial alcohol, etc., corn and other crops planted and reserved as a backup, reduction of rice exports under shortage conditions, fewer forced deliveries, greater availability of food crops in the marketplace, and the rational and humane use of stockpiled rice.

I'm still on the fence as to whether it can be categorically asserted that all famines are entirely preventable. But it's clear that some of the worst famines in recent history were, indeed, tragedies that could have been averted had a scrap more attention been paid to such matters as logistics and basic economics. Had such care been paid to Vietnam in 1945, the nation's postwar fate would likely have been very different.